Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 15

Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause in Breast Cancer Survivors: Current Perspectives on the Role of Laser Therapy

Authors Cucinella L, Tiranini L, Cassani C, Martella S, Nappi RE

Received 24 April 2023

Accepted for publication 3 August 2023

Published 8 August 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 1261—1282

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S414509

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Everett Magann

Laura Cucinella,1,2 Lara Tiranini,1,2 Chiara Cassani,1,3 Silvia Martella,4 Rossella E Nappi1,2

1Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Pediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy; 2Research Centre for Reproductive Medicine, Gynecological Endocrinology and Menopause, IRCCS San Matteo Foundation, Pavia, Italy; 3Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, IRCCS San Matteo Foundation, Pavia, Italy; 4Unit of Preventive Gynecology, IRCCS European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy

Correspondence: Rossella E Nappi, Research Centre for Reproductive Medicine, Gynecological Endocrinology and Menopause, IRCCS San Matteo Foundation, Piazzale Golgi 2, Pavia, 27100, Italy, Tel +390382501561, Fax +390382516176, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a frequent consequence of iatrogenic menopause or anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapies in breast cancer survivors (BCSs). GSM may profoundly affect sexual health and quality of life, and a multidimensional unique model of care is needed to address the burden of this chronic heterogeneous condition. Severe symptoms may be insufficiently managed with non-hormonal traditional treatments, such as moisturizers and lubricants, recommended as the first-line approach by current guidelines, because concerns exist around the use of vaginal estrogens, particularly in women on aromatase inhibitors (AIs). Vaginal laser therapy has emerged as a promising alternative in women with GSM who are not suitable or do not respond to hormonal management, or are not willing to use pharmacological strategies. We aim to systematically review current evidence about vaginal laser efficacy and safety in BCSs and to highlight gaps in the literature. We analyzed results from 20 studies, including over 700 BCSs treated with either CO2 or erbium laser, with quite heterogeneous primary outcomes and duration of follow up (4 weeks– 24 months). Although evidence for laser efficacy in BCSs comes mostly from single-arm prospective studies, with only one randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial for CO2 laser and one randomized comparative trial of erbium laser and hyaluronic acid, available data are reassuring in the short term and indicate effectiveness of both CO2 and erbium lasers on the most common GSM symptoms. However, further studies are mandatory to establish long-term efficacy and safety in menopausal women, including BCSs.

Keywords: genitourinary syndrome of menopause, GSM, vaginal laser, breast cancer, vulvovaginal atrophy, VVA

Introduction

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to the multitude of genital, urinary and sexual symptoms developing in women as a consequence of menopause and age-driven anatomical and functional modifications in urogenital tissues.1 Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, burning, itching and discomfort are the typical clinical manifestations of vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), also known as atrophic vaginitis, the genital component of the syndrome.2 The broader GSM definition includes also urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency and urinary tract infections) and sexual impact, highlighting a common physio-pathological pattern dictated by a decrease in sex hormones, particularly estrogens, after menopause.2 Even age-related and/or iatrogenic decline in androgen levels may play a role in the clinical manifestation of GSM.3

Breast cancer survivors (BCSs) are particularly vulnerable to develop urogenital symptoms and sexual problems, as a consequence of cancer treatments, which may result in iatrogenic and often premature menopause or may worsen pre-existing conditions related to hypoestrogenism.4,5 Indeed, GSM is estimated to affect about half of healthy menopausal women,6 whereas BCSs may display a higher prevalence of urogenital symptoms, reaching up to 70%.7 Chemotherapy and anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapies [gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-A), tamoxifen (TMX) and aromatase inhibitors (AIs)] represent the biological insult predisposing to atrophic changes in the urogenital tissues; however, several psycho-social contributors may modulate the presence and severity of urogenital and sexual symptoms in BCSs,8 and attitudes toward treatments.9 Women taking AIs usually report more frequent and severe GSM symptoms compared with those on TMX, possibly because of a more profound state of iatrogenic hypoestrogenism;10 treatment-emergent endocrine symptoms may be so distressing to lead BCSs to early discontinuation.11

Objective vulvovaginal signs are highly present12 but there is still a lack of early recognition in routine clinical practice that prevents BCSs from receiving adequate care.13 In general, women presenting with cancer expect their healthcare providers (HCPs) to counsel them about the implications of their condition, including potential effects on sexual function.14 HCPs do not proactively ask about GSM symptomatology, likely because they do not feel confident in prescribing treatments specific to BCSs,15 and only half of the oncologists (48%) directly illustrate possible chronic consequences of GSM.16 That being so, GSM remains an unmet medical need.17 According to the most recent guidelines and recommendations,18–22 not all treatment options available for GSM are suitable for BCSs and, therefore, effective management is challenging. Non-hormonal therapies, namely lubricants with sexual activity and regular use of long-acting vaginal moisturizers, are the first-line approach in women with hormone-sensitive breast cancer (BC), whereas data are presently insufficient to confirm safety of some hormonal options [vaginal estrogen or vaginal prasterone or ospemifene, an oral selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)] and their use remains a shared clinical decision based on the patient’s profile.18–22

In the last decade, energy-based treatments have emerged as a possible non-hormonal option to manage GSM symptoms in menopausal women.23 This minimally invasive technology seemed particularly attractive in BCSs who needed to avoid hormonal exposure.24 Vaginal laser therapy is the most studied technique to improve vaginal health through controlled heat-associated micro trauma in vaginal tissue, which leads to activation of fibroblasts in the extracellular matrix and promotes collagen and elastic fibers deposition, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling.25 Two laser technologies have been tested in women with GSM, the micro ablative fractional carbon dioxide (CO2) laser and non-ablative erbium laser, which differ in wavelength, water absorption and tissue penetration, ultimately determining specific tissue response and remodeling.26 Promising results obtained in clinical samples of natural menopausal women and in BCSs have driven a strong marketing despite an absence of solid efficacy and safety data in long-term studies.27 The main factor accelerating the growth of the laser market was the need of both women and HCPs to fill a very relevant gap in GSM treatment deriving from contraindications or low preferences for hormone therapies.28 However, scientific societies18–20,29,30 and regulatory agencies, e.g. the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), awaits further efficacy and safety data before officially endorsing energy-based techniques for the management of GSM.31

In this article, we systematically reviewed available evidence about vaginal laser efficacy and safety for the treatment of GSM in BCSs. Our aim was to critically discuss data in order to highlight gaps in the literature that should be addressed to eventually define the value of vaginal laser therapy in BCSs among all available therapeutic options.

Materials and Methods

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,32 as outlined in Figure 1. A comprehensive search was performed in PubMed and Embase prior to March 31, 2023 by two authors (LC and LT). The search was conducted using relevant MeSH terms (“urogenital system”, “menopause”, “vulvovaginitis”, “laser therapy”, “breast neoplasms”), and keywords (“genitourinary syndrome of menopause”, genitourinary, GSM, “vulvovaginal atrophy”, VVA, “laser therapy”, laser, “breast cancer”) related to vaginal laser therapy, GSM and BC (see Supplementary Appendix for Complete Search Strategy). Reference lists from existing reviews to identify additional relevant studies not identified by the electronic searches were also checked. Studies investigating both CO2 laser and erbium laser were included. Clinical studies of any design, including interventional and observational, retrospective and prospective, were considered eligible. Publications on peer-review journals, written in English and for which the full text of the article was available were included. Case reports and conference abstracts were excluded from this review because of incomplete data. There were no restrictions on the study time period. Independent review of the full-text manuscripts of the selected studies was performed by two authors (LC and LT) and cases of disagreement were solved by discussion of two other researchers (CC and SM). Two authors (LC and REN) independently extracted and collected the following data: number and characteristics of participants (age, menopause duration and/or age, history of BC and use of adjuvant treatments), study design, type of intervention and therapeutic protocol, duration of follow up, main outcomes, incidence of adverse events, results and author conclusions.

|

Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study selection flow diagram. |

Results

With the search strategy described, we identified 108 eligible articles; after the first screening, 36 articles were retrieved and full text assessed for eligibility. Of them, 16 were excluded (15 conference abstracts and one case report), leading to a total of 20 studies included in the present review.33–52 All studies were written in English and published between 2016 and 2023. We included three studies reporting different outcomes in the same treated cohort or new information about extended follow-up periods;41,45,47 we also included two studies from the same research group, reporting outcomes at different stages of patient enrollment.33,35 The majority of studies included only BCSs, with the exception of 4 retrospective studies, 3 of which also evaluated laser treatment in healthy menopausal women38,42,46 and one in gynecological cancer survivors.39 That being so, we calculated that 789 BCSs were included in the studies: 731 of them were treated with vaginal laser (626 with micro ablative CO2 laser, 105 with non-ablative erbium laser)33–52 and 21 participants received local hyaluronic acid treatment as control arm.52

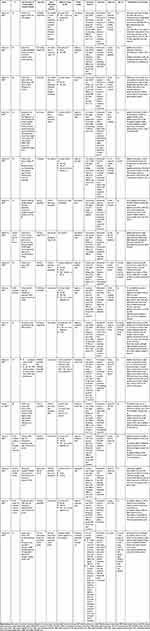

The type of laser used varied across studies and most of them reported use of the micro ablative CO2 laser;33–48 only 4 studies investigated the non-ablative erbium laser.48–52 Looking at the study design, the majority were single arm prospective studies reporting changes in clinical outcomes (most commonly symptom severity) and appearance of vaginal epithelium [usually evaluated through the Vaginal Health Index1 (VHI)] from baseline to follow up; observation times were quite variable, ranging from 4 weeks to a maximum of 24 months. Retrospective studies were also common, while a comparison with local hyaluronic acid was reported only in one randomized trial with erbium laser.52 Our search identified only one double-blinded randomized sham-controlled trial in the BCSs population.48 Results reported in individual studies are displayed in Table 1 for fractional micro ablative CO2 laser and in Table 2 for erbium laser.

|

Table 1 Summary of Included Studies on Fractional Micro Ablative Vaginal Laser in Breast Cancer Survivors (BCSs) |

|

Table 2 Summary of Included Studies on Non-Ablative Vaginal Erbium Laser in Breast Cancer Survivors (BCSs) |

Micro Ablative Fractional CO2 Laser

Sixteen studies33–48 evaluated the efficacy and safety of fractional CO2 laser in 626 BCSs treated for GSM (Table 1). The micro ablative fractional CO2 laser was used with rather homogeneous power settings (power 30–40 W, dwell time of 1000 μs, dot spacing of 1000 μm, smart stack parameter of 1–3). Most women underwent 3 sessions of vaginal laser 30–45 days apart, with few exceptions. Outcomes were reported after each treatment and times at follow up were variable after the last treatment, ranging from 4 weeks to 24 months; four studies also reported vulvar treatment with a dedicated probe.38,41,42,46 Overall, every study observed an improvement in signs and/or symptoms of GSM at short-term follow up, with only few mild adverse events (AEs). Of note, most of the studies were single-arm prospective or retrospective observational studies, with the unique exception of one randomized sham-controlled trial.48

In 2016, Pagano et al were the first to publish results of a study on fractional micro ablative CO2 laser efficacy specifically in a cohort of young BCSs, mostly with iatrogenic menopause and treated with GnRH-A plus TMX.33 In their retrospective observational study, the authors observed a reduction of visual analogue scale (VAS) for dyspareunia, dryness and itching of 78%, 80% and 75%, respectively, after three vaginal laser sessions; dysuria, vaginal bleeding and vaginal discharges were also frequently resolved.33 Similar results were replicated and later published by the same group, after expanding the cohort to 82 BCSs; patients were enrolled after failure of non-hormonal treatments (moisturizers or lubricants) and the majority of them were on anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapies (37 women on AIs and 23 women on TMX); in this cohort, neither age nor the type of adjuvant systemic anticancer therapy seemed to affect treatment outcomes.35

Three further observational retrospective cohort studies investigated efficacy of fractional micro ablative CO2 laser in BCSs cohorts as opposed to healthy menopausal women, reporting similar amelioration of vulvovaginal symptoms42,46 and sexual function by using validated scales.38,46 By contrast, another retrospective comparison observed a slower improvement of symptoms measured by VAS scores in BCSs in respect with healthy menopausal women, possibly as a consequence of more severe GSM symptoms at baseline.43 In a large multi-centric retrospective study involving 135 BCSs and 60 women with a history of some other gynecological cancers, Angioli et al reported a decrease in VAS score for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, pain at the introitus, burning and itching; results were significant in the whole cohort and when the two groups were analyzed separately.39

A similar improvement in GSM signs and symptoms was confirmed in prospective studies. Quick et al published three subsequent papers reporting short- and long-term follow up from a single arm prospective study evaluating 67 menopausal BCSs complaining of dyspareunia and/or vaginal dryness, with more than 90% of subjects treated with anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy (mostly AIs).41,45,47 The initial publication in 2019 reported the feasibility of fractional micro ablative CO2 as a GSM treatment, with 59 women having completed 3 vaginal and vulvar laser sessions without relevant AEs.41 A significant improvement in subjective genital and urinary symptoms, as well as sexual function and distress, measured by the female sexual function index (FSFI) and the female sexual distress scale (FSDS), respectively, was found; even objective signs of VVA, including vaginal pH, improved but the level of significance was not mentioned.41 Afterwards, a study amendment allowed investigators to prolong follow up to 12 and 24 months in order to evaluate lasting improvement over time; among 59 women who completed the original study, data from 39 and 33 women were collected at 12 and 24 months follow up, respectively. The median FSFI score was lower at 12 months compared with 4 weeks, but still significantly higher than at baseline, while there was a trend for FSDS score to decrease during the same time frame, suggesting a sustained improvement in sexual distress; no significant changes in FSFI and FSDS scores were observed between 12 and 24 months follow up.45 A lingering positive effect of laser treatment was observed for genital but not for urinary symptoms.47 A similar trend of response was reported by Veron et al in their study involving 46 BCSs, showing maximum improvement of sexual function and urinary distress at 2 and 6 months follow up, respectively; at 18 months, sexual function decreased but remained significantly higher than at baseline, with the exception of pain and desire domains, whereas urinary distress almost reverted to pre-treatment scores.42

Several prospective studies reported current or past use of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy but only a few of them investigated the impact of these drugs on laser treatment response. In a recent prospective feasibility study, a population of 20 BCSs was divided into 2 groups, according to the past (group 1) and current (group 2) use of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy.44 The authors proposed a protocol with increased number of laser sessions (5 rather than 3) and a progressive increase in laser energy, based on the assumption that severely atrophic vaginal mucosa in BCSs may require a gradual and prolonged exposure for optimal response. At 20-week follow up, more than 70% of women considering the whole sample were satisfied with treatment and both groups reported a similar significant improvement of vulvovaginal symptoms.44 Also sexual function and quality of life (QoL), assessed through the FSFI and the 12-items short form survey (SF-12), respectively, significantly improved in a similar manner between the two groups.44 Pieralli et al conducted the only study prospectively investigating the effect of different types of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy or no treatment in a sample of 50 BCSs with oncological menopause and reporting dyspareunia related to VVA.34 A significant improvement in median VHI across all groups, irrespective of the use and type of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy, was found; of note, only 2 BCSs were assuming AIs and 20 were on TMX.34 Other pilot studies found improvement of GSM symptoms37,40,41 and sexual function37,40 or distress41 in women using different types of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapy, but the small sample size did not allowed subgroup analyses.

Becorpi et al published a study on a small sample of menopausal BCSs who completed various adjuvant treatments, with the aim to investigate the impact of CO2 laser on vaginal microbiome and cytokine profile and their role in improving GSM symptoms.36 No change in composition of vaginal microbiome was documented after CO2 laser treatment, despite an improvement in clinical signs and symptoms, whereas a significant change in cytokines secretory pattern was evident after laser treatment. The reduced concentration of some pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL2 and IL-7) and the increase of some cytokines and growth factors involved in tissue remodeling (IL-18, CTACK, LIF, M-CSF) suggested local immunity as a possible mediator of the effect of CO2 laser on vaginal mucosa.36

The results of a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial specifically evaluating efficacy of vaginal CO2 in a sample of BCSs on AIs therapy have been recently published.48 The primary objective of the study was to identify differences in sexual function changes (evaluated through FSFI) after 5 sessions of vaginal CO2 laser versus an inactive sham treatment.48 Of note, participants from both groups were instructed to use non-hormonal local moisturizing therapy and vaginal vibrator throughout the study period, and possibility of sexual counselling was offered to each patient. Overall, in the whole cohort the authors reported a significant improvement in sexual function and in most of the secondary subjective (VAS scale for dyspareunia, Spanish Body Image scale, VHI) and objective (vaginal pH, vaginal maturation index and histologically evaluated vaginal epithelial elasticity) outcomes, with the exception of quality of life and vaginal epithelial thickness; however, there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms.48

Non-Ablative Erbium Laser

Four studies49–52 specifically assessed efficacy and safety of vaginal erbium laser in BCSs, with variable study protocols (1–3 laser sessions) and energy settings (see Table 2). In a prospective longitudinal pilot study involving 43 menopausal BCSs with GSM symptoms, Gambacciani et al described improvement in subjective VAS scores for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia and in VHI scores at 12-month follow up after 3 sessions of vaginal erbium laser.49 A not statistically significant trend for persistence of beneficial effects after 18 months from the last laser application was evident.49 An improvement in VHI scores was also observed after a single vaginal erbium application in the study of Mothes et al, with 94% of subjective satisfaction; however, the sample size was very small and included an old BCSs sub-population who had a previous surgery for prolapse.50 In another small sample of menopausal BCSs who were in half of the cases on current TMX therapy, Arêas et al reported a significant improvement in VHI score and sexual function measured by the Short Personal Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ), with study follow up limited to one month.51

A recent randomized trial by Gold et al reported a comparison between vaginal erbium laser and local hyaluronic acid in BCSs with urogenital atrophy; they enrolled 43 women, with either vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urgency/dysuria and/or recurrent urinary tract infections, who were randomly allocated to vaginal erbium laser (2 sessions 30 days apart) or to hyaluronic acid vaginal suppositories (daily for 10 days and then three times a week for 12 weeks in total).52 At 12 weeks follow-up, there was a significant improvement in VHI in both arms, without any difference between erbium laser and hyaluronic acid.52 Moreover, bother related to symptoms of urogenital atrophy, dyspareunia and urgency appeared significantly reduced after both interventions, whereas stress urinary incontinence was significantly less bothersome only following laser treatment.51 Several domains of QoL were improved in both treatment arms, while sexual satisfaction and other domains of sexual function did not change, with the exception of sexual pain which improved only following laser treatment. Patients in both groups reported a slight subjective impression of improvement [evaluated through patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I)].52 Overall, the authors concluded that both hyaluronic acid and vaginal erbium laser were safe options to manage GSM-related symptoms, with superimposable outcomes.52

Discussion

Overall, the studies included in Table 1 and Table 2 support a positive impact of vaginal laser treatment on signs and symptoms of GSM in the outpatient setting, with no relevant AEs and a high rate of tolerability which improved with treatment cycles. Around 700 BCSs have been treated mostly in monocentric studies with small sample size, uncontrolled designs and short follow-up times. The majority of studies33–35,37–39,41–43,45–47 performed a total of 3 laser sessions over around 3 months. Clinical characteristics of BCSs were quite heterogeneous, as well as treatment protocols and study outcomes. Duration of effects seemed to last up to 640,42,44 and 12 months.43,45,47,49 Retrospective comparisons in cross-sectional studies38,43,46 not showing significant difference in efficacy of CO2 laser between healthy menopausal women and BCSs were of limited value. According to one study, it seemed likely that a higher number of laser sessions are needed to obtain better results in BCSs.44 The paucity of AEs in BCSs40,42,48,51 was reassuring but evidence of few cases reporting complications such as fibrosis, scarring, agglutination, and penetration injury in healthy menopausal women53 required long-term follow up especially in women severely deprived of estrogens and, therefore, at potential higher risk of complications due to more fragile tissues.4,5 The procedure was generally well tolerated, but tolerance was significantly lower for CO2 laser than sham in the comparative study.48 When clearly reported in studies,44,50 satisfaction with laser procedures was high.

As indicated in previous systematic54–56 and narrative reviews,57 we confirmed that several key questions still await to be answered before vaginal laser treatment may be fully recognized for clinical use on a large scale. Vaginal laser treatment might be effective in treating GSM in BC survivors in the short term but the quality of evidence was rated “very low” in BC survivors and other oncological samples with sexual problems.58

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies in healthy menopausal women with GSM diagnosis treated with different CO2-laser devices and technologies reached similar conclusions.59–61 On the other hand, when only the few randomized clinical trials that compared CO2 laser with sham among healthy menopausal women with GSM diagnosis were included, a significant improvement of vaginal, sexual and urinary scores with a high rate of satisfaction was reported.62 Moreover, a small pilot, multi-institutional randomized sham-controlled trial of women with gynecological cancers with dyspareunia and/or vaginal dryness did not show a significant effect on subjective GSM symptoms, other than a mild significant effect on sexual function, but noted some physical exam improvements in the active treatment arm and supported safety.63 However, the most recent double-blinded sham-controlled randomized trials in healthy menopausal women found a similar improvement of GSM symptoms following sham or laser treatment,64–66 a finding replicated in the recent trial of Mension et al, the first sham controlled one to include BCSs, more specifically those at higher risk of severe genital symptoms because of AIs therapy.48 An insightful state-of-the-art review67 concluded that the effect of vaginal and vulvar laser treatment decreased with higher study quality and only eliminating potential bias with an adequate statistical power, in comparison with approved GSM treatments and sham lasers, will help to solve the issue. Placebo and sham-intervention conditioning effects might also interfere with clinical results depending on the quality of the outcomes.68 Indeed, potential subsets of patients, i.e. those with vaginal dryness as most bothersome symptoms, may benefit to a higher extent following laser as compared with sham.66

Interestingly, an experimental model of VVA induced by iatrogenic menopause in the ewe failed to show substantial differences between tissues treated with sham manipulations or non-ablative erbium laser sessions and supported a more prominent increase in epithelial thickness and higher vaginal compliance in estrogen-replaced ewes.69 This has been partially confirmed in the study by Mension et al, showing no effect of either CO2 laser or sham treatment on vaginal epithelial thickness and a comparable improvement in vaginal epithelial elasticity in both treatment arms.48 On the other hand, histological findings deriving from both CO2 and erbium vaginal laser treatments,70 as well as measurement of increased epithelial thickness, have been available in clinical samples.71,72 Moreover, iconographic representations, i.e. colposcopy images, documented beneficial effects of laser treatment on vulvovaginal tissues36,73 supporting both safety and satisfaction reported in the majority of the studies included in Tables 1 33–48 and 2 49–52 and in other clinical samples treated for GSM.74,75 Even so, the correlation between tissue changes induced by laser treatment and clinical outcomes has been questioned76 and controversy might be solved in study designs with laser technology that will take into account the complex interplay of subjective factors influencing the clinical relevance of treating objective signs.77

Of note, as an item of the vaginal health index (VHI), a validated scale to rate GSM signs subjectively by HCPs,78 vaginal pH was the only objective GSM parameter associated with vaginal hypoestrogenism2 that has been measured before and after CO2 laser in some studies in BCSs34,36,39–44,48 and in all studies with erbium laser.49–52 The vaginal maturation index (VMI), the other supporting finding of GSM diagnosis which quantifies the percentages of parabasal, intermediate, and superficial cells, indirectly estimating the pattern of tissue hypoestrogenism,2 was considered only in two studies with CO2 laser, being unchanged from baseline to follow up in the study of Vernon et al and improved in the controlled trial of Mension et al, but without significant differences between laser and sham group.42,48 Even though vaginal pH and VMI are routinely assessed in clinical trials to prove effects of a given treatment on the vaginal epithelium, they are not essential to make a clinical diagnosis.79 In future investigations at baseline and under sham or laser treatment, an objective noninvasive tool to assess severity of GSM signs might be 3D high frequency vaginal ultrasound (US), which allows measuring of the anterior and posterior walls of the vagina separately.80 Indeed, at variance with transabdominal US-measured vaginal wall thickness or total mucosal thickness which did not show a difference between GSM symptomatic and asymptomatic women,81 3D vaginal US displayed correlations with age, time since menopause and sexual domains (arousal, lubrication, pain, and satisfaction) in a pilot study conducted in women with and without GSM symptoms.80 Other objective indicators may be changes of the vaginal microbiota and inflammatory factors according to some evidence36,82,83 that needs to be further confirmed.

At present, bothersome symptoms, namely pain with sex, vulvovaginal dryness, vulvovaginal discomfort or irritation, and discomfort or pain when urinating, should be the core outcomes guiding research trials and clinical practice in order to manage GSM effectively.84 As a matter of fact, a significant number of menopausal women reported a plethora of GSM symptoms with an impact on urogenital health, QoL and sexual function that was not consistent with the severity of GSM at genital examination.85–87 This could translate in a delay in receiving effective care because menopausal women under appropriate treatment reported significantly more frequent and severe GSM symptoms in comparison with those who were untreated.88 Interestingly, in a sample of menopausal women with a history of breast or endometrial cancer who sought treatment for vulvovaginal symptoms, clinical gynecological exam findings did not correlate with the information reported by the patient about vulvovaginal dryness and discomfort.89 Data regarding the effects of CO2 (Table 1) and erbium (Table 2) laser in BCSs were mostly on typical VVA symptoms, whereas urinary symptoms were poorly explored with validated scales.41,42,47,52 As far as sexual dysfunction was concerned, sexual function changes following CO2 laser treatment were measured in several studies (Table 1) by a validated scale (female sexual function index, FSFI)36–38,41,42,44–48 with psychometric properties that have been recently reassessed in BCSs,90 whereas changes of sexual distress (female sexual distress scale, FSDS), an essential element to establish the clinical relevance of sexual symptoms,91 were measured only in 5 studies following CO2 laser treatment (Table 1).36,38,40,45,47 Only in one study with erbium laser52 (Table 2) psychometric tools validated in the oncologic setting were used. Therefore, high-quality randomized clinical trials and long-term follow up are warranted in BCSs with a GSM clinical diagnosis, taking into account the biopsychosocial challenges affecting sexual health, intimacy and QoL.92,93 Appropriate sexual health screening tools, including cancer and treatment-specific questions, and QoL instruments validated in BCSs should be used to measure patient-reported outcomes and provide comprehensive care.94,95 Indeed, the oncological setting amplified the needs of a multidimensional unique model of care to address menopausal symptoms and sexual problems including conventional and nonconventional medications, stress management, pelvic floor exercises and any other behavioral strategy able to target self-efficacy.96–99

It is important to underline that local hyaluronic acid, a non-hormonal treatment able to improve vaginal health in menopausal women,100 was the only comparator used in BCSs so far with effects superimposable to those of erbium laser.52 Results did not seem so convincing in light of several methodological shortcomings including substantial differences in treatment delivery and adherence.53 Comparative studies with other non-hormonal approaches would be similarly limited by the fact that most of them have been predominantly studied in healthy postmenopausal women and there is a paucity of efficacy data supporting the use of a standard treatment for GSM in BCSs.101 Implementation of adequately powered double-blinded sham-controlled trials appears the ideal solution to establish efficacy and safety in BCSs taking into account age, body mass index, smoking, pre- or postmenopausal status at the time of diagnosis, time since menopause, previous hormone use, type of chemotherapy and current or past use of anti-estrogenic adjuvant therapies, type of most bothersome symptoms, as well as their duration and severity, frequency of sexual activity, partnership, and any other aspect with relevance in GSM diagnosis. Indeed, studies reported in Tables 1 33–48 and 2 49–52 were underpowered to perform meaningful statistical analyses regarding some of these variables that might affect clinical outcomes. Finally, limitations in prescribing hormonal treatments as comparators of laser treatment in BCSs with a history of estrogen-dependent tumors should also be considered. Hormonal treatments may be used after the failure of non-hormonal treatments in women taking TMX and prescribed in women taking AIs after shared decision-making with patient, gynecologist and oncologist.18–22

In the cohort published by Gardner & Aschkenazi46 (Table 1), there was a retrospective comparison between topical estrogen and two CO2 laser sessions showing a not statistically significant difference following 13 weeks when treatments were concomitant. A systematic review and meta-analysis including randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that compared the use of fractional CO2 laser with standard estrogen therapies (conjugated estrogens, estriol, promestriene) showed almost superimposable positive outcomes on GSM signs and symptoms evaluated with subjective and objective measurements.102 Also comparison of laser therapy with other hormonal treatments potentially safe in BCSs, such as vaginal prasterone103 and oral ospemifene,104 may expand the range of treatment options available in menopausal women105 and in high-risk patients with GSM.106 An aspect deserving further investigation is the possibility to combine laser therapy with other treatment strategies to maximize and/or maintain long-term positive effects. This approach could balance risks and benefits in BCSs, taking into account level of evidence and women’s preferences, as well as containing elevated costs for the healthcare system.

This systematic review has limitations that need to be considered. Some studies did not provide information about clinical characteristics, including data about menopausal stage or use and type of adjuvant endocrine therapy, which appear relevant in the authors’ view to interpret the results. Other studies’ characteristics, including design, sample size and outcome heterogeneity, have been acknowledged as major factors limiting the quality of available data.

Conclusions

Effective management of GSM is one of the pillars of menopausal care to enhance sexual well-being and QoL.107 BC alone accounts for almost one-third of all incident cases of cancer in the US in 2022 with 5-year relative survival rates of 90% in women.108 Given GSM is a chronic heterogeneous condition highly prevalent as women age,109 the unmet medical need for safe GSM therapies remains large in BCSs. Vaginal laser therapy represents a great opportunity to fill the gap providing symptoms relief and restoring tissues, in the meantime avoiding estrogen exposure. Available data are reassuring in the short term and indicate effectiveness of both CO2 and erbium lasers on the most common GSM symptoms. However, further studies are mandatory to prove long-term efficacy and safety in menopausal women, including BCSs. Very importantly, it remains to be established who are the women that might benefit most from these minimally invasive techniques according to their own specific properties.26,110

Disclosure

Professor Rossella E. Nappi had past financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards and/or consultant) with Boehringer Ingelheim, Ely Lilly, Endoceutics, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer Inc, Procter & Gamble Co, TEVA Women’s Health Inc. and Zambon SpA. At present, she has ongoing relationships with Abbott, Astellas, Bayer HealthCare AG, Exceltis, Fidia, Gedeon Richter, HRA Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Organon & Co, Shionogi Limited and Theramex, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Shifren JL. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(3):508–516. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000380

2. Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000329

3. Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, et al. The role of androgens in the treatment of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM): International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Menopause. 2018;25(7):837–847. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001138

4. Falk SJ, Bober S. Vaginal Health During Breast Cancer Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(5):32. doi:10.1007/s11912-016-0517-x

5. Cox P, Panay N. Vulvovaginal atrophy in women after cancer. Climacteric. 2019;22(6):565–571. doi:10.1080/13697137.2019.1643180

6. Nappi RE, Martini E, Cucinella L, et al. Addressing Vulvovaginal Atrophy (VVA)/Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) for healthy aging in women. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:561. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00561

7. Lester J, Pahouja G, Andersen B, Lustberg M. Atrophic vaginitis in breast cancer survivors: a difficult survivorship issue. J Pers Med. 2015;5(2):50–66. doi:10.3390/jpm5020050

8. Crean-Tate KK, Faubion SS, Pederson HJ, Vencill JA, Batur P. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in female cancer patients: a focus on vaginal hormonal therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(2):103–113. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.043

9. Biglia N, Cozzarella M, Cacciari F, et al. Menopause after breast cancer: a survey on breast cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2003;45(1):29–38. doi:10.1016/s03785122(03)00087-2

10. Santen RJ, Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Pinkerton JV, Gompel A, Lumsden MA. Managing menopausal symptoms and associated clinical issues in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3647–3661. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01138

11. Smith KL, Verma N, Blackford AL, et al. Association of treatment-emergent symptoms identified by patient-reported outcomes with adjuvant endocrine therapy discontinuation. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):53. doi:10.1038/s41523-022-00414-0

12. Nappi RE, Palacios S, Bruyniks N, Particco M, Panay N; EVES Study Investigators. The European Vulvovaginal Epidemiological Survey (EVES). Impact of history of breast cancer on prevalence, symptoms, sexual function and quality of life related to vulvovaginal atrophy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(1):78–82. doi:10.1080/09513590.2020.1813273

13. Cook ED, Iglehart EI, Baum G, Schover LL, Newman LL. Missing documentation in breast cancer survivors: genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause. 2017;24(12):1360–1364. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000926

14. Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Matthews AC. A manifesto on the preservation of sexual function in women and girls with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):166–174. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.039

15. Kingsberg SA, Larkin L, Krychman M, Parish SJ, Bernick B, Mirkin S. WISDOM survey: attitudes and behaviors of physicians toward vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) treatment in women including those with breast cancer history. Menopause. 2019;26(2):124–131. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001194

16. Biglia N, Bounous VE, D’Alonzo M, et al. Vaginal atrophy in breast cancer survivors: attitude and approaches among oncologists. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(8):611–617. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2017.05.008

17. Biglia N, Del Pup L, Masetti R, Villa P, Nappi RE. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) in breast cancer survivors (BCS) is still an unmet medical need: results of an Italian Delphi Panel. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(6):2507–2512. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-05272-4

18. The NAMS 2020 GSM Position Statement Editorial Panel. The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27(9):976–992. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001609

19. Faubion SS, Larkin LC, Stuenkel CA, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25(6):596–608. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001121

20. “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society” Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29(7):767–794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

21. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Clinical Consensus—Gynecology. Treatment of urogenital symptoms in individuals with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer: clinical consensus. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(6):950–960. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004601

22. Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):492–511. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.75.8995

23. Hillard TC, Nappi RE. The heat is on. Climacteric. 2020;23(sup1):S1–S2. doi:10.1080/13697137.2020.1828855

24. Biglia N, Bounous VE, Sgro LG, D’Alonzo M, Pecchio S, Nappi RE. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors: are we facing new and safe hopes? Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15(6):413–420. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2015.06.005

25. Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429–436. doi:10.1007/s10103-014-1677-2

26. Hillard TC. Lasers in the era of evidence-based medicine. Climacteric. 2020;23(sup1):S6–S10. doi:10.1080/13697137.2020.1774536

27. Adelman M, Nygaard IE. Time for a “Pause” on the use of vaginal laser. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1378–1380. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.14809

28. Nappi RE, Murina F, Perrone G, Villa P, Biglia N. Clinical profile of women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy who are not candidates for local vaginal estrogen therapy. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(4):370–380. doi:10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04064-3

29. Shobeiri SA, Kerkhof MH, Minassian VA, Bazi T; IUGA Research and Development Committee. IUGA committee opinion: laser-based vaginal devices for treatment of stress urinary incontinence, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and vaginal laxity. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(3):371–376. doi:10.1007/s00192-018-3830-0

30. Phillips C, Hillard T, Salvatore S, Cardozo L, Toozs-Hobson P; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Laser treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: scientific impact Paper No. 72 (July 2022). BJOG. 2022;129(12):e89–e94. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.17195

31. US Food and Drug Administration [homepage on the Internet]. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal “rejuvenation” or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fdawarns-against-use-energy-based-devices-perform-vaginal-rejuvenation-or-vaginal-cosmetic.

32. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

33. Pagano T, De Rosa P, Vallone R, et al. Fractional microablative CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy in women treated with chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy for breast cancer: a retrospective study. Menopause. 2016;23(10):1108–1113. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000672

34. Pieralli A, Fallani MG, Becorpi A, et al. Fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) dyspareunia relief in breast cancer survivors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(4):841–846. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4118-6

35. Pagano T, De Rosa P, Vallone R, et al. Fractional microablative CO2 laser in breast cancer survivors affected by iatrogenic vulvovaginal atrophy after failure of nonestrogenic local treatments: a retrospective study. Menopause. 2018;25(6):657–662. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001053

36. Becorpi A, Campisciano G, Zanotta N, et al. Fractional CO2 laser for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors: clinical, immunological, and microbiological aspects. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(5):1047–1054. doi:10.1007/s10103-018-2471-3

37. Pearson A, Booker A, Tio M, Marx G. Vaginal CO2 laser for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer: LAAVA pilot study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(1):135–140. doi:10.1007/s10549-019-05384-9

38. Gittens P, Mullen G. The effects of fractional microablative CO2 laser therapy on sexual function in postmenopausal women and women with a history of breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2019;21(3):127–131. doi:10.1080/14764172.2018.1481510

39. Angioli R, Stefano S, Filippini M, et al. Effectiveness of CO2 laser on urogenital syndrome in women with a previous gynecological neoplasia: a multicentric study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30(5):590–595. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2019-001028

40. Hersant B, Werkoff G, Sawan D, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy in women treated for breast cancer: preliminary results of the feasibility EPIONE trial. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2020;65(4):e23–e31. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2020.05.002

41. Quick AM, Zvinovski F, Hudson C, et al. Fractional CO2 laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause for breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3669–3677. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-05211-3

42. Veron L, Wehrer D, Annerose-Zéphir G, et al. Effects of local laser treatment on vulvovaginal atrophy among women with breast cancer: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;188(2):501–509. doi:10.1007/s10549-021-06226-3

43. Siliquini GP, Bounous VE, Novara L, Giorgi M, Bert F, Biglia N. Fractional CO₂ vaginal laser for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2021;27(5):448–455. doi:10.1111/tbj.14211

44. Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Casiraghi A, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy in women with a history of breast cancer: a pilot study at 4-week follow-up. Clin Breast Cancer. 2021;21(5):e539–e546. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2021.01.006

45. Quick AM, Zvinovski F, Hudson C, et al. Patient-reported sexual function of breast cancer survivors with genitourinary syndrome of menopause after fractional CO2 laser therapy. Menopause. 2021;28(6):642–649. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001738

46. Gardner AN, Aschkenazi SO. The short-term efficacy and safety of fractional CO2 laser therapy for vulvovaginal symptoms in menopause, breast cancer, and lichen sclerosus. Menopause. 2021;28(5):511–516. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001727

47. Quick AM, Hundley A, Evans C, et al. Long-term follow-up of fractional CO2 laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Med. 2022;11(3):774. doi:10.3390/jcm11030774

48. Mension E, Alonso I, Anglès-Acedo S, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide vs sham laser on sexual function in survivors of breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the LIGHT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255697. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55697

49. Gambacciani M, Levancini M. Vaginal erbium laser as second-generation thermotherapy for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a pilot study in breast cancer survivors. Menopause. 2017;24(3):316–319. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000761

50. Mothes AR, Runnebaum M, Runnebaum IB. Ablative dual-phase Erbium:YAG laser treatment of atrophy-related vaginal symptoms in post-menopausal breast cancer survivors omitting hormonal treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(5):955–960. doi:10.1007/s00432-018-2614-8

51. Arêas F, Valadares ALR, Conde DM, Costa-Paiva L. The effect of vaginal erbium laser treatment on sexual function and vaginal health in women with a history of breast cancer and symptoms of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a prospective study. Menopause. 2019;26(9):1052–1058. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001353

52. Gold D, Nicolay L, Avian A, et al. Vaginal laser therapy versus hyaluronic acid suppositories for women with symptoms of urogenital atrophy after treatment for breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas. 2022;167:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.08.013

53. Gordon C, Gonzales S, Krychman ML. Rethinking the techno vagina: a case series of patient complications following vaginal laser treatment for atrophy. Menopause. 2019;26(4):423–427. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001293

54. Knight C, Logan V, Fenlon D. A systematic review of laser therapy for vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:988. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2019.988

55. Jha S, Wyld L, Krishnaswamy PH. The impact of vaginal laser treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19(4):e556–e562. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2019.04.007

56. D’Oria O, Giannini A, Buzzaccarini G, et al. Fractional Co2 laser for vulvo-vaginal atrophy in gynecologic cancer patients: a valid therapeutic choice? A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;277:84–89. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.08.012

57. Jugulytė N, Žukienė G, Bartkevičienė D. Emerging use of vaginal laser to treat genitourinary syndrome of menopause for breast cancer survivors: a review. Medicina. 2023;59:132. doi:10.3390/medicina59010132

58. Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Douskos A, Salvatore S, Loutradis D, Grigoriadis T. Intravaginal energy-based devices and sexual health of female cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35(1):1–11. doi:10.1007/s10103-019-02855-9

59. Filippini M, Porcari I, Ruffolo AF, et al. CO2-laser therapy and genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2022;19(3):452–470. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.12.010

60. Liu M, Li F, Zhou Y, Cao Y, Li S, Li Q. Efficacy of CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy: a meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158(2):241–251. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13973

61. Mension E, Alonso I, Tortajada M, et al. Vaginal laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause - systematic review. Maturitas. 2022;156:37–59. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.06.005

62. Khamis Y, Abdelhakim AM, Labib K, et al. Vaginal CO2 laser therapy versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2021;28(11):1316–1322. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001845

63. Quick AM, Dockter T, Le-Rademacher J, et al. Pilot study of fractional CO2 laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in gynecologic cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2021;144:37–44. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.10.018

64. Cruff J, Khandwala S. A double-blind randomized sham-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy on genitourinary syndrome of menopause. J Sex Med. 2021;18(4):761–769. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.01.188

65. Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1381–1389. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.14892

66. Page AS, Verbakel JY, Verhaeghe J, Latul YP, Housmans S, Deprest J. Laser versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2022. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.17335

67. Mortensen OE, Christensen SE, Løkkegaard E. The evidence behind the use of LASER for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, vulvovaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence and lichen sclerosus: a state-of-The-art review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101(6):657–692. doi:10.1111/aogs.14353

68. Pérez-López FR, Varikasuvu SR. Vulvovaginal atrophy management with a laser: the placebo effect or the conditioning Pavlov reflex. Climacteric. 2022;25(4):323–326. doi:10.1080/13697137.2022.2050207

69. Mackova K, Mazzer AM, Mori Da Cunha M, et al. Vaginal Er:YAG laser application in the menopausal ewe model: a randomised estrogen and sham-controlled trial. BJOG. 2021;128(6):1087–1096. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16558

70. Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159. doi:10.1002/lsm.22637

71. Dutra PFSP, Heinke T, Pinho SC, et al. Comparison of topical fractional CO2 laser and vaginal estrogen for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2021;28(7):756–763. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001797

72. Gaspar A, Silva J, Calderon A, Di Placido V, Vizintin Z. Histological findings after non-ablative Er:YAG laser therapy in women with severe vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2020;23(sup1):S11–S13. doi:10.1080/13697137.2020.1764525

73. Perino A, Calligaro A, Forlani F, et al. Vulvo-vaginal atrophy: a new treatment modality using thermo-ablative fractional CO2 laser. Maturitas. 2015;80(3):296–301. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.12.006

74. Lang P, Dell JR, Rosen L, Weiss P, Karram M. Fractional CO2 laser of the vagina for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: is the out-of-pocket cost worth the outcome of treatment? Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(10):882–885. doi:10.1002/lsm.22713

75. Di Donato V, O D, Scudo M, et al. Safety evaluation of fractional CO2 laser treatment in post-menopausal women with vaginal atrophy: a prospective observational study. Maturitas. 2020;135:34–39. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.02.009

76. Preti M, Vieira-Baptista P, Digesu GA, et al. The clinical role of LASER for vulvar and vaginal treatments in gynecology and female urology: an ICS/ISSVD best practice consensus document. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(3):1009–1023. doi:10.1002/nau.23931

77. Cucinella L, Martini E, Tiranini L, et al. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: should we treat symptoms or signs? Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2022;22:100386. doi:10.1016/j.coemr.2022.100386

78. Castelo-Branco C, Mension E. Are we assessing genitourinary syndrome of menopause properly? Climacteric. 2021;24(6):529–530. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1945573

79. Phillips NA, Bachmann GA. The genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause. 2021;28(5):579–588. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001728

80. Balica AC, Cooper AM, McKevitt MK, et al. Dyspareunia Related to GSM: association of Total Vaginal Thickness via Transabdominal Ultrasound. J Sex Med. 2019;16(12):2038–2042. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.019

81. Peker H, Gursoy A. Relationship between genitourinary syndrome of menopause and 3D high-frequency endovaginal ultrasound measurement of vaginal wall thickness. J Sex Med. 2021;18(7):1230–1235. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.05.004

82. Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518. doi:10.1080/13697137.2016.1212006

83. Sipos AG, Pákozdy K, Jäger S, Larson K, Takacs P, Kozma B. Fractional CO2 laser treatment effect on cervicovaginal lavage zinc and copper levels: a prospective cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):235. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01379-1

84. Lensen S, Bell RJ, Carpenter JS, et al. A core outcome set for genitourinary symptoms associated with menopause: the COMMA (Core Outcomes in Menopause) global initiative. Menopause. 2021;28(8):859–866. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001788

85. Palacios S, Nappi RE, Bruyniks N, Particco M, Panay N; EVES Study Investigators. The European Vulvovaginal Epidemiological Survey (EVES): prevalence, symptoms and impact of vulvovaginal atrophy of menopause. Climacteric. 2018;21(3):286–291. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1446930

86. Nappi RE, Palacios S, Bruyniks N, Particco M, Panay N; EVES Study investigators. The burden of vulvovaginal atrophy on women’s daily living: implications on quality of life from a face-to-face real-life survey. Menopause. 2019;26(5):485–491. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001260

87. Particco M, Djumaeva S, Nappi RE, Panay N, Palacios S; EVES Study investigators. The European Vulvovaginal Epidemiological Survey (EVES): impact on sexual function of vulvovaginal atrophy of menopause. Menopause. 2020;27(4):423–429. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001496

88. Panay N, Palacios S, Bruyniks N, Particco M, Nappi RE; EVES Study investigators. Symptom severity and quality of life in the management of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2019;124:55–61. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.013

89. Flynn KE, Lin L, Carter J, et al. Correspondence between clinician ratings of vulvovaginal health and patient-reported sexual function after cancer. J Sex Med. 2021;18(10):1768–1774. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.07.011

90. Kieseker GA, Anderson DJ, Porter-Steele J, McCarthy AL. A psychometric evaluation of the Female Sexual Function Index in women treated for breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2022;11(6):1511–1523. doi:10.1002/cam4.4516

91. Nappi RE. New attitudes to sexuality in the menopause: clinical evaluation and diagnosis. Climacteric. 2007;10(Suppl 2):105–108. doi:10.1080/13697130701599876

92. Mension E, Alonso I, Castelo-Branco C. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: current treatment options in breast cancer survivors - systematic review. Maturitas. 2021;143:47–58. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.08.010

93. Vegunta S, Kuhle CL, Vencill JA, Lucas PH, Mussallem DM. Sexual health after a breast cancer diagnosis: addressing a forgotten aspect of survivorship. J Clin Med. 2022;11(22):6723. doi:10.3390/jcm11226723

94. Tounkel I, Nalubola S, Schulz A, Lakhi N. Sexual health screening for gynecologic and breast cancer survivors: a review and critical analysis of validated screening tools. Sex Med. 2022;10(2):100498. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2022.100498

95. Mlakar I, Lin S, Nateqi J, et al. Establishing an expert consensus on key indicators of the quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a modified delphi study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):2041. doi:10.3390/jcm11072041

96. Hickey M, Emery LI, Gregson J, Doherty DA, Saunders CM. The multidisciplinary management of menopausal symptoms after breast cancer: a unique model of care. Menopause. 2010;17(4):727–733. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d672f6

97. Lubián López DM. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors: an update. World J Clin Oncol. 2022;13(2):71–100. doi:10.5306/wjco.v13.i2.71

98. Faubion SS, Kingsberg SA. Understanding the unmet sexual health needs of women with breast cancer. Menopause. 2019;26(8):811–813. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001372

99. Vizza R, Capomolla EM, Tosetto L, et al. Sexual dysfunctions in breast cancer patients: evidence in context. Sex Med Rev. 2023:qead006. doi:10.1093/sxmrev/qead006

100. Nappi RE, Martella S, Albani F, Cassani C, Martini E, Landoni F. Hyaluronic acid: a valid therapeutic option for early management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in cancer survivors? Healthcare. 2022;10(8):1528. doi:10.3390/healthcare10081528

101. Garzon S, Apostolopoulos V, Stojanovska L, Ferrari F, Mathyk BA, Laganà AS. Non-oestrogenic modalities to reverse urogenital aging. Prz Menopauzalny. 2021;20(3):140–147. doi:10.5114/pm.2021.109772

102. Jang YC, Leung CY, Huang HL. Comparison of severity of genitourinary syndrome of menopause symptoms after carbon dioxide laser vs vaginal estrogen therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2232563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.32563

103. Mension E, Alonso I, Cebrecos I, et al. Safety of prasterone in breast cancer survivors treated with aromatase inhibitors: the VIBRA pilot study. Climacteric. 2022;25(5):476–482. doi:10.1080/13697137.2022.2050208

104. Cai B, Simon J, Villa P, et al. No increase in incidence or risk of recurrence of breast cancer in ospemifene-treated patients with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA). Maturitas. 2020;142:38–44. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.021

105. Nappi RE, Cucinella L, Martini E, Cassani C. The role of hormone therapy in urogenital health after menopause. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(6):101595. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2021.101595

106. Salvatore S, Benini V, Ruffolo AF, et al. Current challenges in the pharmacological management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022. doi:10.1080/14656566.2022.2152326

107. Simon JA, Davis SR, Althof SE, et al. Sexual well-being after menopause: an International Menopause Society White Paper. Climacteric. 2018;21(5):415–427. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1482647

108. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

109. Mili N, Paschou SA, Armeni A, Georgopoulos N, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review on prevalence and treatment. Menopause. 2021;28(6):706–716. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001752

110. Tranoulis A, Georgiou D, Michala L. Laser treatment for the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause after breast cancer. Hope or hype? Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(11):1879–1886. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-04051-3

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.