Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

From Corporate Social Responsibility to Employee Well-Being: Navigating the Pathway to Sustainable Healthcare

Authors Ahmad N , Ullah Z, Ryu HB , Ariza-Montes A , Han H

Received 22 November 2022

Accepted for publication 27 March 2023

Published 5 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1079—1095

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S398586

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Naveed Ahmad,1,2 Zia Ullah,3 Hyungseo Bobby Ryu,4 Antonio Ariza-Montes,5 Heesup Han6

1Faculty of Management, Department of Management Sciences, Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan; 2Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan; 3Leads Business School, Lahore Leads University, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan; 4Foodservice & Culinary Art, Department of the College of Health Sciences, Kyungnam University, Changwon-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea; 5Social Matters Research Group, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, Spain; 6College of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Correspondence: Hyungseo Bobby Ryu; Heesup Han, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: Despite extensive research on the impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee outcomes, only limited research has been conducted to investigate the impact of CSR on healthcare employees’ burnout (BUO). Additionally, the underlying mechanism by which CSR may reduce BUO has not been fully understood. In order to fill these gaps, we explored the relationship between CSR and BUO, as well as the possible mediating effects of subjective wellbeing (SW) and compassion (CM). Also, employee admiration (AM) was examined as a moderating factor.

Methods: The study utilized a questionnaire to collect data, which was distributed using the paper-pencil method. A total of 335 healthcare employees, including nurses, doctors, paramedics, and general administration, participated in the study. Specifically, we focused on the healthcare segment of Pakistan. A survey was conducted to assess participants’ perceptions of CSR practices, BUO, AM, SW, and CM within their organizations. The questionnaire consisted of several standardized scales validated in previous research.

Results: We investigated the relationship between CSR and BUO using the AMOS software. BUO was negatively associated with CSR, suggesting that organizations with strong CSR practices may be able to reduce employee burnout. Moreover, the relationship between CSR and BUO was mediated by both subjective wellbeing (SW) and compassion (CM), revealing how CSR may impact employee burnout. Furthermore, we found that employee admiration (AM) buffered the relationship between CSR and BUO.

Findings: BUO is a growing concern among healthcare professionals and has the potential to negatively impact the quality of patient care, staff morale, and, ultimately, the success of healthcare organizations. BUO in healthcare settings can be effectively addressed by implementing CSR strategies. Effective CSR strategies should be implemented in a meaningful way to employees and provide them with opportunities to engage in activities that align with their values and interests.

Keywords: mental health, wellbeing, burnout, healthcare, CSR

Introduction

Burnout (BOU) is not a medical condition. Still, it may predict serious health issues including, but not limited to, heart diseases, musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal pain and even cardiovascular issues. According to WHO Disease Classification (ICD-11), Unmanaged work-related stress leads to BUO.1 There are three categories of BUO based on theory: exhaustion and personal energy depletion, job-related mental dissonance, and a decreased level of professional effectiveness. There are some professions where employees feel more symptoms of being burned out. Perhaps, on top of such professions, is healthcare, where an escalating number of employees’ BUO has been reported worldwide.2,3 Even empirical evidence suggests that BUO in healthcare had reached a crisis level before the current pandemic, as the rate of BUO in healthcare was around 60%.4 BUO has been linked to anxiety, depression, and emotional exhaustion by organizational scientists.5,6 Precisely BUO in healthcare has different negative consequences for patients and organizations. At a patient level, burned-out employees may undermine patients’ healthcare delivery standards, increasing medical errors and infection rates.7,8 At an organizational level, the manifestation of BUO among healthcare employees can create a staffing shortage. Moreover, BUO creates a cost constraint for organizations because empirical evidence suggests that BUO-related turnover in healthcare has a multibillion-dollar cost (almost 9 billion).9

Fixing BUO in an organizational context may require individual support, but largely for an effective solution to BUO, a system-oriented (organizational level) approach has been suggested by various scholars recently.10,11 In this respect, different organizational interventions have been proposed previously to mitigate BUO risk among employees. For example, different scholars have proposed different leadership styles as a system-oriented solution for BUO.12,13 Likewise, organizational factors like culture14 and HR policies15 have been linked with BUO.

We aim to extend the discussion on BUO in the corporate social responsibility (CSR) framework, which is an under-researched area to date. CSR has been cited as a powerful influencer of employee behaviors in recent literature, such as creativity,16–18 pro-social behavior,19–21 innovative behavior,22 organizational citizenship behavior,23 and various others. At the same time, literature also relates CSR to reducing employees’ stress,24 emotional exhaustion,25 etc. Though CSR plays an important role in predicting/influencing various employee outcomes, little attention has been paid to studying BUO within a CSR framework.26 Especially the mechanism to explain how and why CSR relates to BUO remained an underexplored terrain.

In this respect, CSR practices are increasingly being recognized as an effective tool to reduce the risk of employee BUO in healthcare.27 CSR practices can reduce employee burnout and promote employee well-being in a sector (healthcare, for example) where employees are constantly exposed to high levels of stress and burnout.28 In healthcare, CSR practices can take many forms, including charitable activities, community service, sustainable and ethical practices, and employee wellness programs. These practices are not only beneficial to society, but they also provide a range of benefits to the organizations that implement them. One of the most significant benefits of CSR practices in healthcare is their ability to promote a sense of purpose and engagement among employees.29 Healthcare professionals who are disconnected from the larger purpose of their work are at high risk of experiencing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, which are key symptoms of burnout. By implementing CSR practices that promote community service and social responsibility, healthcare organizations can provide employees with opportunities to engage in activities that align with their personal values and interests.30 This can help them feel a greater sense of purpose and connection to their work, which can reduce burnout. Furthermore, CSR practices can also help to improve job satisfaction among healthcare professionals, which is another key factor in reducing burnout.31 Employees who feel a sense of pride and satisfaction in their work are less likely to experience burnout. CSR practices that promote ethical practices and environmental responsibility can create a positive work environment that fosters a sense of social responsibility and shared purpose. This can improve employee engagement and job satisfaction, which are key factors in mitigating burnout.

The objectives of this study are twofold. First, this study tends to close the critical gap in past literature by investigating the CSR-BUO relationship in healthcare, which was not focused on previously. The second goal of this study is to understand how subjective wellbeing (SW), compassion (CM), and admiration (AM) interact, as mediators and a moderator, to make sense of the CSR-BUO relationship. The plea for understanding the above underlying mechanism lies in the argument by Glavas,32 who argued that employee psychology could be better explained by the presence of psychological mediators or moderators in a CSR framework. The other authors have also acknowledged the importance of mediators and moderators to better explain individual psychology.33,34 To this end, the discussion on the mediating roles of SW and CM35,36 and the moderating role of emotions (AM is also an emotional state) already exists.37,38 Thus, mediators and moderators can help us understand the underlying mechanisms of the CSR-BUO relationship.

Overall, BUO and healthcare management literature are both enriched by this study in two ways. With the help of two mediators (SW and CM) and one moderator (AM), this study investigates the CSR-BUO relationship in the healthcare context for the first time. Previously, BUO studies were not carried out in a CSR framework, and if such literature existed,28 extant scholars have failed to explain this relationship’s underlying mechanism. Through the use of two mediators and one moderator, this study attempts to explain the underlying mechanism of CSR and BUO. CSR may therefore explain how and why healthcare employees’ BUO is associated with CSR as a result of the outcomes of this study. A second contribution of this study is to extend the discussion of employees’ BUO phenomenon within the healthcare sector of a developing country. Previous studies have mostly focused on employees’ BUO in developed or high-income countries’ healthcare sectors.39,40 There were few studies on BUO in high-income countries, even within the CSR framework.41 Two specific reasons may explain why studies conducted in high-income or developed countries may not reflect conditions in developing countries. In developing countries, healthcare workers face more difficult workplace conditions due to a lack of resources compared to their counterparts in developed countries.26,42 Secondly, CSR is a context and cultural-specific variable.43,44 Due to this, CSR literature from developed countries may not be representative of the CSR situation in developing countries. Therefore, there is a need to carry-out a separate investigation to examine BUO among healthcare employees in a CSR framework.

Theory and Hypotheses

The current research focuses on a popular theory called conservation of resources (CNR) to explain employee BUO.45,46 Having its origin in the study by Hobfoll,47 CNR suggests that a particular individual is assumed to access, develop and preserve different valuable resources which may be helpful in fixing a certain kind of uncertain situation in a workplace. Taking this into account, Lin and Liu28 argued that a company’s CSR policies improve employee mental health and wellbeing, reducing employee perceptions of resource depletion while resolving a certain challenging situation. Indeed in his later study Hobfoll realized that in an enterprise milieu, resources include different things, including contextual support from an organization. For example, when employees achieve something, the ethical support of an organization in the form of acknowledgment or appreciation may boost their morale and motivation level (a kind of personal resource), which ultimately strengthens employees’ will to fight back against the epic of BUO.48

CSR and Burnout Association

It is the ethical context of an organization that helps employees improve their wellness and mental health, resulting in a reduction of their BUO. Additionally, scholars like Yan, Tang49 have argued that CSR from the standpoint of CNR is a significant social and contextual support that influences employees’ positive psychology, thereby improving their work performance. Hobfoll, Halbesleben50 indicated that as a crossover in an organization may create a BUO climate, an ethical organization focusing on CSR can expedite positive crossover where positive outcomes and experiences may energize employees more and more and ultimately reducing the chances of BUO. Chen, Huang,51 in a recent study, mentioned that the CSR context of an ethical enterprise creates a working environment that triggers different psychological aspects of positive employee psychology, for example, vigor and motivation, which work as added resources to reduce BUO risk in a workplace. An ethical organization’s social and contextual support may inspire employees to feel proud52 to serve in an organization that focuses on the benefit of all stakeholders, both internal (employees, for example) and external (customers, society, environment, etc.). A sense of pride in one’s work provides employees with extra energy, thus reducing the risk of BUO.53 It is, therefore, possible to propose the following hypothesis:

H1: CSR negatively predicts employees’ BUO in an organizational setting

CSR, Subjective Wellbeing and Burnout Association

Conceptually, in a workplace context, SW has been described as the emotional and rational assessment by an employee of how his/her employer improves his/her wellness.54 The prior literature has indicated that SW promotes employees’ mental health and assists them in preventing work-related negative outcomes, including BUO.55 CSR has been shown to influence employee perceptions of SW positively in the existing literature on CSR and employee psychology.56,57 As an organizational enabler, the CSR policy of an ethical corporation creates different policy structures to improve employees’ wellbeing, for example, providing them with flexible working conditions and providing them with the necessary resources, especially in crisis times.58 The ethical focus of a CSR-oriented organization converts the workforce into happy workers with improved mental health. To this end, empirical evidence clearly acknowledges that happy workers are more energetic, motivated, and resilient and show an improved life satisfaction level.59,60 Specifically, under the CSR policy, an ethical enterprise takes different employee-level interventions to boost their SW levels. Past literature indicates that SW not only directly relates to BUO but it also explains it as a mediator. For example, in a recent survey, Hunsaker61 argued that spiritual leadership (an organizational factor) influences the SW of employees in an organization which then mediates to explain the BUO of employees. The other scholars also highlighted the mediating role of SW in predicting different employee outcomes, including stress and depression.62 Even the mediation mechanism of SW in CSR literature to explain different employees’ outcomes exists in prior literature.63,64 To conclude, as the existing literature indicates that SW mitigates BUO perception of employees, and because CSR can determine SW, we propose:

H2: The SW of employees in an organization is positively impacted by CSR H3: In an organizational setting, SW mediates between CSR and BUO

CSR, Compassion and Burnout Association

David65 defined CM as the intention of a person to spare time and resources for the welfare of other persons. In an organizational setting, employee CM means a specific employee’s willingness to help others, for example, employees/colleagues/customers, etc. Precisely, CM is considered a basic personal characteristic in healthcare because most individuals join this profession for the welfare of humanity.66 Especially CM among healthcare workers can be linked with the suffering and distress of others (patients, for example). Compassionate healthcare workers are self-motivated to take different measures for the removal of others’ suffering.67 Intriguingly, empirical evidence demonstrates that CM benefits not only receivers, but also providers. Specifically, Lown, Shin68 believed that when compassionate individuals see the steps taken by them to mitigate others’ suffering, they feel positive emotions and become more energetic and enthusiastic. Such positive feelings and a greater level of personal energy then serve as a base of additional resources which do not let a person to be a mere victim of BUO.69 Hofmeyer, Taylor70 indicated that compassionate workers are more resilient and energetic against the epic of BUO. Therefore, they are less likely to be overwhelmed due to BUO risk.

Conceptually, CSR and CM share the same concern, which is to focus on others’ welfare and wellbeing. Indeed, Guzzo, Wang71 have argued in their recent study that employees’ CM is positively affected by a firm’s CSR efforts. The early studies conducted by different social scientists revealed that the ethical steps taken by a firm for the welfare of others infuse positive feelings among employees, which then determine their attitude and behavior.72 Rupp, Ganapathi73 were of the view that CSR-related actions by a firm predict different behaviors of employees, including extra-role behaviors. Moreover, employees have favorable associations with an ethical firm due to its CSR commitment to the collective wellbeing of others.74 Indeed, Zedeck75 held the view that CSR-based actions of a firm can motivate employees to be involved in different discretionary actions, including CM. A variety of employee outcomes have been discussed in the literature regarding the mediating role of CM.76,77 From the standpoint of CSR, recent scholars like Guzzo, Wang,71 Ali, Islam,78 and Hur, Moon16 have proposed the mediating role of CM to explain various employee outcomes. We can propose the following hypotheses based on the above discussion and literature.

H4: CSR-based actions positively predict the CM of employees in an organizational setting H5: In an organizational setting, CM mediates between CSR and BUO

Admiration as Moderator

Theoretically, AM relates to the emotional appraisal and evaluation of a target based on different actions taken by that target.79 Genuinely AM is an emotional aspect of individual psychology that influences different attitudes and behaviors.80 Psychological studies on positive individual psychology indicate that positive emotions motivate people to adopt positive attitudes and behaviors.81,82 In this respect, plenty of literature documents a positive relationship between CSR and positive individual emotions.83,84 Indeed, research specifies that the social engagement of a firm infuses different positive emotions among employees, for example, gratitude85 and engagement.86 From an organizational standpoint, AM on the part of employees may relate to the CSR-based actions of a firm because when employees see the social commitment of their firm, it influences their psychology positively, thereby giving rise to the feeling of admiration. Indeed, Cegarra‐Navarro and Martínez‐Martínez87 were convinced that to promote feelings of admiration, CSR is essential. Immordino-Yang and Sylvan80 mentioned that the origin of AM can be linked with the morality and ethical engagement of a target (the organization in the current context). Similarly, Keltner and Haidt88 argued that individuals express the feelings of AM for a target because of moral virtues. They further stated that the observation of moral virtues by the individuals, motivate them to develop admired feeling for a specific target. Barchiesi and La Bella89 stated that AM employees consider themselves to be workers of a socially responsible company that promotes the collective wellbeing of all stakeholders.

In positive employee psychology, emotions play an important role in predicting different employee outcomes.90,91 Even scholars have argued that positive individual emotions can strengthen SW92 and CM.93 Because the line between individual emotions and individual outcomes already exists at different levels and because emotions can give rise to different attitudes and responses, we propose that in an organizational setting, the CSR-based actions of a firm improve employees’ AM feelings which then buffers between CSR and SW and CM. Therefore;

H6: AM moderates the mediating link between CSR and BUO via SW in an organizational setting H7: AM moderates the mediating link between CSR and BUO via CM in an organizational setting

The hypothesized relationships have been shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The hypothesized structural framework. |

Methodology

Unit of Analysis, Sample, and Procedure

This study collected data from healthcare workers from Pakistan, a South Asian lower-middle-income nation. In this study, individual employees were the unit of analysis. The data for this survey were collected from Karachi and Lahore, two metropolitan cities. We intentionally selected the cities for this survey in order to meet our objectives. The underlying reason for selecting Karachi and Lahore is that in both cities, a multi-million population resides whose public health issues have been dealt with by the healthcare workers in different public and private hospitals. Regrettably, the public health status, especially in larger cities of Pakistan, has been worrisome due to different climatic and social issues. Air pollution, contaminated drinking water and poor health literacy are some of the leading factors contributing to the poor public health stats in Pakistan.94 Especially, Lahore has been announced many times as a city in the world with the most polluted air quality.95–97 Similarly, Karachi is also among the top ten most polluted cities in the world.98,99 Currently, the average life expectancy in Pakistan is marginally above 65 years which is far below compared to neighboring nations like Iran (77 years)100 and Sri Lanka (77.39).101 Poor environmental conditions in Pakistan, especially in mega-cities,19 create public health challenges that increase pressure on hospitals by creating an overburdening situation. Huge patient traffic and limited resources make the job of healthcare workers more demanding, thereby increasing BUO risk. Therefore, carrying out this survey in these cities is important from the perspective of employees’ BUO in the healthcare.

Although there are different public hospital structures in Pakistan, however majority of patients have been attended by private sector hospitals. The private hospital industry attends to almost 60% of patients, according to a recent estimate.102 Accordingly, we contacted hospital administrators whose hospitals had any type of CSR program. There are a number of CSR activities being conducted by large private hospitals. We requested the hospital administration in such hospitals in Karachi and Lahore to support us in this data-collecting activity. To this end, we were able to receive a positive response from seven hospitals (four from Lahore and three from Karachi). The data collection exercise involved employees from different departments, for example, healthcare service providers (physician, nurse, paramedics) and general administration. Precisely the data were gathered between the months of March and May 2022.

Instrument and Measures

In this study, healthcare workers were asked to fill out a questionnaire. This was a self-administered one for which the variable-related items were taken from different published literature. A panel of experts from academia and healthcare was asked to evaluate the statements in the questionnaire. Other researchers have also highlighted the importance of this step.103–105 The questionnaire comprised three parts, including an informed consent form,106,107 followed by socio-demographic questions. Lastly, the variables-related information was collected on a five-point Likert scale.98,108 By taking different measures, we avoided issues like social desirability and common method variance (CMV). The variable statements were presented randomly to respondents, for instance.109,110 Similarly, the data were gathered in three independent waves separated by a two-week gap. Moreover, Helsinki Declaration’s ethical norms were also followed.111,112 In this data collection activity, both males and females contributed, but the male contribution (59%) was higher than the female contribution. As well, the maximum number of employees were 18 to 45 years old (87%). In most cases, employees had between 1 and 10 years of experience.

Specifically, CSR was quantified by considering 12-items from the famous and reliable scale by Turker.113 Other authors have also used the same scale.114 Example items from this scale were “This organization participates in activities that aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment (general CSR) and “This organization implements flexible policies to provide a good work environment and life balance for its employees (employee-related CSR). We adapted the reliable scale by Kristensen, Borritz115 to quantify BUO, which included 7-items (“I feel worn out at the end of the working day” and “I am exhausted in the morning at the thought of another day at work”). SW and AM were quantified by using the scales of Lyubomirsky and Lepper,116 who developed the SW scale to measure employee perceptions regarding their wellbeing. The original scale consisted 4-items, among which an example item was “In general, I consider myself a very happy person.” For AM, we used 5-item from the study of Sweetman, Spears.117 Sample item from this scale includes “I feel admiration when I think about this organization.” Finally, CM, we used 3-items from the work by Lilius, Worline.118 A sample item was “How frequently do you experience compassion on the job?” The inter-item consistency of all variables indicated that all values were significant (>.7). Specifically, we observed alpha values for CSR = 0.92, BUO = 0.88, SW =0.82, AM = 0.87 and CM= 0.83.

We used AMOS (version 22) software to detect CMV empirically to perform a common latent factor (CLF) test. Our approach was to develop two measurement models, one of which was the base model, which included five factors without any manifestation of CLF. Introducing a CLF into the measurement model is part of the second model. For a significant variance (>.20), the standardized factor loadings of the two models were observed. However, we revealed that no significant variance existed in any factor loading of the two models, confirming that the manifestation of CLF did not create any significant difference. This was an indication of the absence of CMV. Our single confirmatory factor analysis also showed poor fit statistics, confirming the non-criticality of CMV.

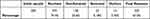

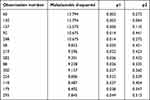

Sample Size and Data Cleaning

Through an online calculator, a sample size was estimated for this survey developed by Daniel.119 This specific tool has been specially designed for structural equation modeling (SEM) and estimates sample size based on different inputs, including the number of variables (observed vs latent), estimated effect size (we set it at medium level, which is 0.25), probability level (we set it at 0.5), etc. The calculator suggested a minimum sample size of 248. In this vein, we initially provided the respondents with five hundred questionnaires. We finally received 372 filled responses from the healthcare employees. After data cleaning, we removed 37 questionnaires (23 were partially filled, and the remaining were outliers). For more information, we recommend seeing Table 1 and Table 2.

|

Table 1 Data Cleaning Summary |

|

Table 2 Outliers |

Results

Initial results

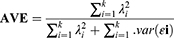

The initial results section included a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a validity and reliability analysis, a model fitness test, and a correlation test. First of all, we ensured that no variable’s item factor loading was below the minimum acceptable value (<.5).120,121 For this purpose, the standardized item loadings were checked during a CFA analysis which indicated that all values were significant and no item’s factor loading was below 0.7 indicating that the associated error term was not producing a dominant variance in a variable. To calculate the average variance extracted (AVE) for each variable individually, we used the formula below (Equation 1).

It was revealed that AVEs were all significant (>.5).122,123 Convergent validity was evident for CSR (0.61), BUO (0.65), SW (0.56), CM (0.58), and AM (0.73), indicating that the items were converging to their respective variables (for example, 12 items were well converging on CSR).

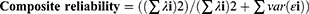

Connately, we executed a reliability test, especially a composite reliability test, for which the formula (Equation 2) given below was used.

The empirical evidence suggested that a significant value of composite reliability (>.7)124 existed in all cases (CSR =0.95, BUO =0.93, SW =0.83, CM =0.81, AM = 0.93). We have summarized the above statistical analyses in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Summary of Initial Analyses |

Commensurately, we tested whether our theoretical model fit the empirical data well. A total of four measurement models were developed in AMOS, with one (model 1) serving as a baseline model (originally hypothesized five factors) and the other three being alternate models (2, 3, and 4). All four measurement models were analyzed to draw conclusions for this analysis. With this regard, it was observed that a one-factor model poorly explained the data (RMSEA = 0.212, and χ2/df = 7.82, GFI = 0.36, TLI = 0.35, IFI =, 0.38, CFI = 0.40) whereas, the baseline model explained the data excellently, confirming that the baseline model was a perfect model for this dataset (RMSEA = 0.058, and χ2/df = 2.36, GFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, IFI =, 0.93, CFI = 0.93). Model 2 and 3 produced mixed results (some values were good some were not), but no one of them was able to undermine the superiority of model 1. Table 4 includes further information.

|

Table 4 Model Fitness |

We concluded the initial results section by reporting correlation (r) among different pairs of variables. The summary of the correlation test is given in Table 5. According to the output of the correlation test, some pairs had a positive r value (for example, CSR and SW= 0.49), whereas some cases established a negative association (for example, CSR and BUO = −0.58). Conceptually, these values were in line with hypotheses statements (for example, hypothesis 1 and 2). Moreover, all r values were significant (p<0.05 or 0.01). Accordingly, no correlational value was critical (≥ 0.8), confirming that multicollinearity was not an issue in this analysis. Lastly, we also tested the divergent validity (bold diagonal values in Table 5) values for all variables (CSR =0.78, BUO = 0.80, SW =0.75, CM =0.85, AM = 0.76).

|

Table 5 Correlations and Discriminant Validity |

Main Results

After successfully finishing the initial result phase, we moved forward to the main results (hypotheses testing). Our study tested the hypothesized relationship using SEM, which is an advanced-level analysis technique suited for complex models (such as the one we studied here).125,126 For developing structural analysis, AMOS (version 22) along with SPSS Process-Macro were taken into consideration. Specifically, the Process-Macro helped us to draw different equations for testing different hypotheses, especially for conditional indirect effects of AM. For this specific purpose, the guidelines given in model-7 of this Process-Macro template developed by Hayes127 were observed. To transport such information in AMOS, a user-defined estimand option was used. Equally important to mention here is that prior to this main analysis, we calculated the mean-centered values for CSR and AM. Similarly, a 5000 bootstrapping sample was also used to test the mediation and moderation effects.128 In SPSS, an interaction term was also generated by multiplying CSR_X_AM. Firstly, we analyzed the direct effects of CSR→BUO (−.57 for H1), CSR→SW (0.51 for H2), and CSR→CM (0.42 for H4). This analysis confirmed that H1, H2, and H4 were significant (p values were significant in all cases with no zero values between lower and upper confidence intervals = CI). For example the CI for H1 ranged from −0.68 to −0.44, which did not include any zero point. Hence providing statistical support for accepting H1. A similar interpretation may be extracted for H2 and H4.

In the next stage, we analyzed the mediation effects between CSR→SW→BUO (−.48, p<0.05 with non-zero CI values and significant Z-statistics = −13) and CSR→CM→BUO (−.39, p<0.05 with non-zero CI values and significant Z-statistics = −11.8). There was a partial mediation effect between CSR and BUO caused by SW and CM. Hence, H3 and H5 were statistically significant.

Finally, we analyzed the conditional effect of AM between CSR→SW (−.36, p<0.05) and CSR→CM (−.31, p<0.05). This was done by enabling the user-defined estimand option in AMOS. Among the mediated relationships of CSR and BUO through SW and AM, there was a significant conditional indirect effect of AM. This supports the theoretical statements of H6 and H7, confirming that the manifestation of AM buffers employees’ SW and AM levels. Hence, H6 and H7 were also significant. For further detail, one can see the summary in Table 6.

|

Table 6 Hypotheses Results |

Discussion

In light of the statistical results of this research, the major objectives specified in the introduction section can now be discussed. The underlying purpose of this research was to investigate CSR-BUO associations in a developing country’s healthcare sector. Regarding this objective, the statistical evidence suggests that an effective CSR policy in an ethical organization helps employees mitigate BUO risk. Moreover, the achieved statistical findings indicated that CSR negatively predicts BUO (beta = −0.57), which means an ethical organization with effective CSR actions can reduce the likelihood of employees being burned-out.

Additionally, the ethical framework of a hospital supports employees in enhancing their wellness and mental health, which than meager BUO risk. Referring to conservation of resources theory, CSR actions can be regarded as social and contextual resources which influence employees’ positive psychology, thereby improving their work performance and reducing BUO.50 The CSR policies of a hospital develop a workplace environment that triggers different psychological aspects of positive employee psychology, for example, vigor and motivation, which energizes employees more and more not to be mere victims of BUO. Employees may feel proud of working for a socially responsible hospital that benefits all stakeholders as a result of CSR. This sense of pride enhances positive emotion among employees, which in return induces their wellness and mental health. Hence, this study confirms that CSR negatively predicts BUO. This also aligns with previous researchers.49,51

Also, this study sought to understand the underlying mechanisms behind the CSR-BUO relationship with the help of SW and CM as mediators and AM as a moderator. By combining SW, CM, and AM, this study explains how and why CSR negatively predicts BUO. From this standpoint, the manifestation of CSR in an ethical hospital helps employees to improve different psychological and personality-related outcomes, especially SW and CM.

SW improves employees’ perceptions regarding mental health and supports them in the effective management of different work-related outcomes, for example, BUO. CSR is widely acknowledged as having a profound impact on workers’ SW levels. Employees become self-assured that their hospital considers the welfare of all, including them when they see CSR as part of their organization’s ethical considerations. We are in line with Kim, Woo58 in stating that an ethical hospital under its CSR strategy takes different policy interventions to improve employees’ wellbeing, such as providing flexible working conditions and the necessary resources, especially in crisis timings. Our results confirmed that CSR positively predicts SW (beta =0.51), which is in line with previous researchers.58,64 Further, not only the manifestation of CSR in a hospital improves the SW level of employees, but it also helps in understanding the underlying mechanism of the CSR-BUO relationship. In that respect, the improved wellbeing level of employees, as an outcome of CSR, improves the mental health of workers, which then helps them to resist the epic of BUO. Hence this study confirms the mediating effect of SW amidst CSR and BUO (beta = −0.48).

Similarly, our results also establish an improvement in the CM level of healthcare employees due to the CSR actions of their ethical hospital. In that regard, CM and CSR both have a common concern for the welfare of others. When compassionate employees work in an ethical hospital, there is value congruence between the organization and employees, which boosts employees’ morale and energy level to a further level, thereby improving their performance. CM in a healthcare context is one of the fundamentals because most employees join healthcare with a zest to serve humanity.66 Compassionate employees are self-motivated to take different measures to remove others’ suffering. CSR actions of a firm positively affect the employees’ CM. Specifically, the ethical steps taken by a firm for the welfare of others infuse positive feelings among employees, which then determine their positive attitudinal and behavioral intentions. Similarly, employees have favorable associations with an ethical firm due to its CSR commitment to the collective wellbeing of others which then positively determines their CM (beta = 0.42). The finding receives empirical support from the early researchers, too.71 Additionally, in the presence of CM, the underlying mechanism of why CSR meager the effect of BUO among employees becomes more visible. In that respect, our results indicated that CM significantly mediates amidst CSR and BUO (beta = −0.39). The other authors have also acknowledged the mediating role of CM in a CSR framework.16,78

Our results indicate that AM buffers the mediated relationship between CSR and BUO through SW and CM. A person’s attitudes and behaviors are influenced by AM, an emotional aspect of human psychology. Positive individual emotions motivate a person to show positive attitudinal and behavioral responses. Past literature establishes that a positive relationship exists between CSR and positive individual emotions.83,84 Positive emotions such as gratitude and engagement are instilled in employees as a result of the ethical commitment of a hospital organization. A conceptual link between AM and CSR can be drawn because when employees see how their firm is contributing to society, it influences their psychological state positively, creating a feeling of admiration that then buffers SW and CM, reducing BUO further. Hence, we confirm the conditional indirect effect of AM in CSR→SW→BUO and CSR→CM→BUO relationships.

Contributions in Theory

The results of this research contribute significantly to existing knowledge. With the help of two mediators (SW and CM) and one moderator (AM), this is one of the limited investigations exploring the CSR-BUO relationship in the healthcare context. In the past, the literature on BUO, especially in a healthcare context, remained underexplored from the standpoint of CSR. A major contribution of this study is to explain the underlying mechanism of why and how CSR relates to BUO in a healthcare setting. To this end, this study proposed the mediating effects of SW and CM to understand the underlying mechanism of the above relationship. Previously, either the phenomenon of CSR in relation to BUO in the healthcare segment did not exist, or if it existed, the underlying mechanism to explain this relationship was missed by extant scholars. For example, Lin and Liu28 were able to highlight the profound importance of CSR in reducing health workers’ BUO. It was not explained how mediators or moderators can assist in understanding this mechanism.

Second, this study contributes to the established body of knowledge by considering healthcare in a developing country (Pakistan) from the perspective of BUO. In that regard, previously, scholars investigated employees’ BUO in the healthcare segment of developed or high-income countries.39,40 Even in the CSR framework, the sparse explanation of BUO existed from the standpoint of high-income countries.41 By providing a developing country perspective on employees’ BUO, our study contributes to this debate. We feel it was important to carry out such an investigation from the standpoint of a developing economy because CSR is a context and cultural-specific variable.43,44 Thus, CSR literature from developed nations may not be relevant to developing nations. Though, the literature indicates that BUO among healthcare workers is a critical issue in healthcare management globally. However, this study is important because, as compared to developed nations, employees in developing nations face more difficult working and social conditions.

Contribution to the Field

Healthcare administrators can gain different practical insights from this research. First of all, this study demonstrates the profound importance of CSR in minimizing the effects of BUO on employees. It is therefore important for the administration to realize that well-designed and well-executed CSR strategies not only enhance a hospital’s reputation, but also affect different employee outcomes, such as BUO, an escalating problem in healthcare. Due to the financial costs associated with employees’ BUO and the limited resources in the healthcare segment, reducing the BUO of healthcare workers is of utmost importance. At one end, CSR helps a hospital improve BUO perceptions of employees. At another end, it helps a certain hospital from a financial aspect.

A CSR program not only reduces BUO, but also improves healthcare service delivery because employees with better mental health, as an outcome of CSR, tend to be more energetic, and they tend to be more engaged and enthusiastic in serving patients. Similarly, hospital administrators should understand the importance of CSR in influencing positive psychology among their employees, because employees positively evaluate CSR actions performed by ethical hospitals. Specifically, CSR has the potential to induce SW, CM, and AM levels in employees, which are all important to meager BUO risk on employees’ part.

Limitations and Future Suggestions

Undoubtedly, our study enriches both the existing body of research and practice significantly, yet it encounters some limitations. Firstly, this research was carried out in two large cities in Pakistan. The geographic concentration of these cities may limit the generalizability of the research, despite their importance from a data collection perspective. As a remedy, we suggest including more cities in future surveys. Secondly, another limitation of this research lies with the sample representativeness issue. Though the information was collected from different employees in the healthcare segment, we were unable to access any list of employees because there were some policy constraints on the part of hospital administration. We suggest incorporating this limitation in the future by having a list of employees to decide upon sample representativeness. Thirdly, we collected data in this research by following a non-probability method which reduces the strength of a hypothetical model to predict the causality. For this reason, we suggest future researchers to opt for a probability sampling method.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study suggests that there is a seminal role of well-planned and well-executed CSR policies in an ethical hospital organization. It is recommended that the administration carefully plan CSR strategies, especially from the perspective of the employees. Our recommendation is that hospital administration closely align different CSR actions with employee welfare programs. Such collaboration at the one side, will improve the CSR perception of healthcare workers, it will also improve employee wellness at another side. Moreover, we also conclude here that a hospital administration needs to arrange different training sessions, which should be communicated to the employees as a part of the CSR strategy, to improve the CM and SW level of employees. As part of the CSR strategy, such training sessions will induce positive employee psychology, which is expected to improve their resistance level against BUO epic in healthcare management. The ethical engagement of a hospital provides employees with an extraordinary feeling of pleasantness, thereby inducing their emotions and reducing BUO risk. Employees in a socially responsible hospital with better mental health and wellness perceptions will likely show better commitment and energy to fight against BUO.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The present research was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the research program committee of the Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute & Research Center (IRB Proposal No. PKLI-IRB/AL/2021-29/159).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Burnout an “occupational phenomenon”: international classification of diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases.

2. De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171. doi:10.2147/LRA.S240564

3. Maglalang DD, Sorensen G, Hopcia K, et al. Job and family demands and burnout among healthcare workers: the moderating role of workplace flexibility. SSM Popul Health. 2021;14:100802. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100802

4. National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, D.C. USA: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine; 2019. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25521/taking-action-against-clinician-burnout-a-systems-approach-to-professional.

5. Chirico F, Ferrari G, Nucera G, Szarpak L, Crescenzo P, Ilesanmi O. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Health Soc Sci. 2021;6(2):209–220.

6. Trumello C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, et al. Psychological adjustment of healthcare workers in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences in stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction between frontline and non-frontline professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8358. doi:10.3390/ijerph17228358

7. Trockel MT, Menon NK, Rowe SG, et al. Assessment of physician sleep and wellness, burnout, and clinically significant medical errors. JAMA network open. 2020;3(12):e2028111–e. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28111

8. Dyrbye LN, Major-Elechi B, Thapa P, et al. Characterization of nonphysician health care workers’ burnout and subsequent changes in work effort. JAMA network open. 2021;4(8):e2121435–e. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21435

9. Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784–790. doi:10.7326/M18-1422

10. Eric G. Employee burnout is a problem with the company, not the person. Massachusetts, USA: Harvard Business Review; 2017. Available from: https://hbr.org/2017/04/employee-burnout-is-a-problem-with-The-company-not-The-person.

11. Jennifer M. Burnout is about your workplace, not your people. Cambridge, MA, United States; 2019. Available from: https://hbr.org/2019/12/burnout-is-about-your-workplace-not-your-people.

12. Tafvelin S, Nielsen K, von Thiele Schwarz U, Stenling A. Leading well is a matter of resources: leader vigour and peer support augments the relationship between transformational leadership and burnout. Work Stress. 2019;33(2):156–172. doi:10.1080/02678373.2018.1513961

13. Parveen M, Adeinat I. Transformational leadership: does it really decrease work-related stress? Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2019;40(8):860–876. doi:10.1108/LODJ-01-2019-0023

14. Dal Corso L, De Carlo A, Carluccio F, Colledani D, Falco A. Employee burnout and positive dimensions of well-being: a latent workplace spirituality profile analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242267

15. Bakker AB, de Vries JD. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: new explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(1):1–21. doi:10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

16. Hur W-M, Moon T-W, Ko S-H. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. J Bus Ethics. 2018;153(3):629–644. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3321-5

17. Guo M, Ahmad N, Adnan M, Scholz M, Naveed RT, Naveed RT. The relationship of CSR and employee creativity in the hotel sector: the mediating role of job autonomy. Sustainability. 2021;13(18):10032. doi:10.3390/su131810032

18. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Han H, Araya-Castillo L, Ariza-Montes A. Fostering hotel-employee creativity through micro-level corporate social responsibility: a social identity theory perspective. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1.

19. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, Arshad MZ, Waqas Kamran H, Scholz M, Han H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: the mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain Prod Consum. 2021;27:1138–1148. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.034

20. Murtaza SA, Mahmood A, Saleem S, Ahmad N, Sharif MS, Molnár E. Proposing stewardship theory as an alternate to explain the relationship between CSR and Employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability. 2021;13(15):8558. doi:10.3390/su13158558

21. Yu H, Shabbir MS, Ahmad N, et al. A contemporary issue of micro-foundation of CSR, employee pro-environmental behavior, and environmental performance toward energy saving, carbon emission reduction, and recycling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5380. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105380

22. Ahmad N, Scholz M, Arshad MZ, et al. The inter-relation of corporate social responsibility at employee level, servant leadership, and innovative work behavior in the time of crisis from the healthcare sector of Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4608. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094608

23. He J, Zhang H, Morrison AM. The impacts of corporate social responsibility on organization citizenship behavior and task performance in hospitality: a sequential mediation model. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019;31(6):2582–2598. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0378

24. Schwepker CH, Valentine SR, Giacalone RA, Promislo M. Good barrels yield healthy apples: organizational ethics as a mechanism for mitigating work-related stress and promoting employee well-being. J Bus Ethics. 2021;174(1):143–159. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04562-w

25. Xue S, Zhang L, Chen H. CSR, Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intention: perspective of Conservation of Resources Theory.

26. Chen R, Liu W. Managing healthcare employees’ burnout through micro aspects of corporate social responsibility: a public health perspective. Public Health Front. 2022;10:1.

27. Liu Y, Cherian J, Ahmad N, Han H, de Vicente-Lama M, Ariza-Montes A. Internal corporate social responsibility and employee burnout: an employee management perspective from the healthcare sector. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;Volume 16:ahead of print 283–302. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S388207

28. Lin C-P, Liu M-L. Examining the effects of corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership on turnover intention. Pers Rev. 2017;46(3):526–550. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2015-0293

29. Nanayakkara H, Sangarandeniya Y. Employee engagement through corporate social responsibility: a study of executive and managerial level employees of XYZ company in private healthcare services sector. Open J Mod Phys Mang. 2021;10(1):1–16. doi:10.4236/ojbm.2022.101001

30. Lee D. Impact of organizational culture and capabilities on employee commitment to ethical behavior in the healthcare sector. Serv Bus. 2020;14(1):47–72. doi:10.1007/s11628-019-00410-8

31. Abd-Rabou M, Ashry M, Elweshahi H. Measuring social responsibility towards employees in healthcare settings in Egypt and its interrelation to their job satisfaction. Health Ser Manag Res. 2023;2023:09514848231154754.

32. Glavas A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Front Psychol. 2016;796:1.

33. Alfes K, Truss C, Soane EC, Rees C, Gatenby M. The relationship between line manager behavior, perceived HRM practices, and individual performance: examining the mediating role of engagement. Hum Resour Manage. 2013;52(6):839–859. doi:10.1002/hrm.21512

34. Purc E, Laguna M. Personal values and innovative behavior of employees. Front Psychol. 2019;10:865. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00865

35. Gordon S, Tang C-H, Day J, Adler H. Supervisor support and turnover in hotels. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019;31(1):496–512. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0565

36. Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara P, Viera-Armas M, Guo M, Ahmad N, Adnan M, Scholz M. Does supervisors’ mindfulness keep employees from engaging in cyberloafing out of compassion at work? Pers Rev. 2020;49(2):670–687. doi:10.1108/PR-12-2017-0384

37. Fox S, Spector PE, Miles D. Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. J Vocat Behav. 2001;59(3):291–309. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1803

38. Mahipalan M, Sheena S. Workplace spirituality and subjective happiness among high school teachers: gratitude as a moderator. Explore. 2019;15(2):107–114. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2018.07.002

39. Johnson J, Hall LH, Berzins K, Baker J, Melling K, Thompson C. Mental healthcare staff well‐being and burnout: a narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(1):20–32. doi:10.1111/inm.12416

40. Cocchiara RA, Peruzzo M, Mannocci A, et al. The use of yoga to manage stress and burnout in healthcare workers: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):284. doi:10.3390/jcm8030284

41. Huang SY, Fei Y-M, Lee Y-S. Predicting job burnout and its antecedents: evidence from financial information technology firms. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):4680. doi:10.3390/su13094680

42. Bangdiwala SI, Fonn S, Okoye O, Tollman S. Workforce resources for health in developing countries. Public Health Rev. 2010;32:296–318. doi:10.1007/BF03391604

43. Zou Z, Liu Y, Ahmad N, et al. What prompts small and medium enterprises to implement CSR? A qualitative insight from an emerging economy. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):952. doi:10.3390/su13020952

44. Mahmood A, Naveed RT, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Khalique M, Adnan M. Unleashing the barriers to CSR implementation in the sme sector of a developing economy: a thematic analysis approach. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12710. doi:10.3390/su132212710

45. Neveu JP. Jailed resources: conservation of resources theory as applied to burnout among prison guards. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(1):21–42. doi:10.1002/job.393

46. Prapanjaroensin A, Patrician PA, Vance DE. Conservation of resources theory in nurse burnout and patient safety. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2558–2565. doi:10.1111/jan.13348

47. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

48. Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00062

49. Yan A, Tang L, Hao Y. Can corporate social responsibility promote employees’ taking charge? The mediating role of thriving at work and the moderating role of task significance. Front Psychol. 2021;11:613676. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.613676

50. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5:103–128. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

51. Chen W-K, Huang T-Y, Tang AD, Ilkhanizadeh S. Investigating configurations of internal corporate social responsibility for work–family spillover: an asymmetrical approach in the airline industry. Soc Sci. 2022;11(9):401. doi:10.3390/socsci11090401

52. Jia Y, Yan J, Liu T, Huang J. How does internal and external CSR affect employees’ work engagement? Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms and boundary conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2476. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142476

53. Ramdhan RM, Kisahwan D, Winarno A, Hermana D. Internal corporate social responsibility as a microfoundation of employee well-being and job performance. Sustainability. 2022;14(15):9065. doi:10.3390/su14159065

54. Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol. 2002;2:63–73.

55. Qu H-Y, Wang C-M. Study on the relationships between nurses’ job burnout and subjective well-being. Chin Nurs Res. 2015;2(2–3):61–66. doi:10.1016/j.cnre.2015.09.003

56. Hu B, Liu J, Qu H. The employee-focused outcomes of CSR participation: the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2019;41:129–137. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.10.012

57. Golob U, Podnar K. Corporate marketing and the role of internal CSR in employees’ life satisfaction: exploring the relationship between work and non-work domains. J Bus Res. 2021;131:664–672. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.048

58. Kim H, Woo E, Uysal M, Kwon N. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2018;30(3):1584–1600. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-03-2016-0166

59. Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2(4):253–260. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

60. Naseem K. Job stress, happiness and life satisfaction: the moderating role of emotional intelligence empirical study in telecommunication sector Pakistan. J Stud Soc Sci Humanit. 2018;4(1):7–14.

61. Hunsaker W. Spiritual leadership and job burnout: mediating effects of employee well-being and life satisfaction. Manag Sci Lett. 2019;9(8):1257–1268. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2019.4.016

62. McGuire D, McLaren L. The impact of physical environment on employee commitment in call centres. Team Perform Manag. 2009;15(1/2):35–48. doi:10.1108/13527590910937702

63. Ahmed M, Zehou S, Raza SA, Qureshi MA, Yousufi SQ. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: the mediating effect of employee well‐being. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2020;27(5):2225–2239. doi:10.1002/csr.1960

64. AlSuwaidi M, Eid R, Agag G. Understanding the link between CSR and employee green behaviour. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2021;46:50–61. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.11.008

65. David D. How to cultivate gratitude, compassion, and pride on your team Cambridge. MA, USA: Harvard Business Review; 2018:2–4. Available from: https://hbr.org/2018/02/how-to-cultivate-gratitude-compassion-and-pride-on-your-team.

66. Sinclair S, Hack TF, Raffin-Bouchal S, et al. What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: a grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ open. 2018;8(3):e019701. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019701

67. Sinclair S, Russell LB, Hack TF, Kondejewski J, Sawatzky R. Measuring compassion in healthcare: a comprehensive and critical review. Patient Patient-Centeroutcomes Res. 2017;10(4):389–405. doi:10.1007/s40271-016-0209-5

68. Lown BA, Shin A, Jones RN. Can organizational leaders sustain compassionate, patient-centered care and mitigate burnout? J Healthc Manag. 2019;64(6):398–412. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-18-00023

69. Tabaj A, Pastirk S, Bitenc Č, Masten R. Work-related stress, burnout, compassion, and work satisfaction of professional workers in vocational rehabilitation. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2015;58(2):113–123. doi:10.1177/0034355214537383

70. Hofmeyer A, Taylor R, Kennedy K. Fostering compassion and reducing burnout: how can health system leaders respond in the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond? Nurse Educ Today. 2020;94:104502. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104502

71. Guzzo RF, Wang X, Abbott J. Corporate social responsibility and individual outcomes: the mediating role of gratitude and compassion at work. Cornell Hosp Q. 2022;63(3):350–368. doi:10.1177/1938965520981069

72. Cropanzano R, Byrne ZS, Bobocel DR, Rupp DE. Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. J Vocat Behav. 2001;58(2):164–209. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1791

73. Rupp DE, Ganapathi J, Aguilera RV, Williams CA. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: an organizational justice framework. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(4):537–543. doi:10.1002/job.380

74. Farooq O, Rupp DE, Farooq M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: the moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad Manage J. 2017;60(3):954–985. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0849

75. Zedeck SE. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. In: Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization. Vol. 3. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2011.

76. Ali R, Kashif M. The role of resonant leadership, workplace friendship and serving culture in predicting organizational commitment: the mediating role of compassion at work. Rev Bras Gest Neg. 2020;22:799–819.

77. Buonomo I, Farnese ML, Vecina ML, Benevene P. Other-focused approach to teaching. the effect of ethical leadership and quiet ego on work engagement and the mediating role of compassion satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2021;12:2521. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.692116

78. Ali M, Islam T, Mahmood K, Ali FH, Raza B. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: mediating roles of compassion and psychological ownership. Asia Pac Soc Sci Rev. 2021;21:3.

79. Roseman IJ, Spindel MS, Jose PE. Appraisals of emotion-eliciting events: testing a theory of discrete emotions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(5):899. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.899

80. Immordino-Yang MH, Sylvan L. Admiration for virtue: neuroscientific perspectives on a motivating emotion. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2010;35(2):110–115. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.003

81. Sels L, Tran A, Greenaway KH, Verhofstadt L, Kalokerinos EK. The social functions of positive emotions. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2021;39:41–45. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.12.009

82. Schneider CR, Zaval L, Markowitz EM. Positive emotions and climate change. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2021;42:114–120. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.04.009

83. Liu Y, Liu S, Zhang Q, Hu L. Does perceived corporate social responsibility motivate hotel employees to voice? The role of felt obligation and positive emotions. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2021;48:182–190. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.006

84. Del Mar García‐De Los Salmones M, Perez A. Effectiveness of CSR advertising: the role of reputation, consumer attributions, and emotions. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2018;25(2):194–208. doi:10.1002/csr.1453

85. Yan A, Yao M, Chen S, Guo H. An Empirical Study on the Enhancement of Internal and External Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Advocacy Behavior.

86. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Han H, Scholz M. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: the role of work engagement and psychological safety. J Retail Consum Serv. 2022;67:102968. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102968

87. Cegarra‐Navarro JG, Martínez‐Martínez A. Linking corporate social responsibility with admiration through organizational outcomes. Soc Responsib J. 2009;5(4):499–511. doi:10.1108/17471110910995357

88. Keltner D, Haidt J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn Emot. 2003;17(2):297–314. doi:10.1080/02699930302297

89. Barchiesi MA, La Bella A. An analysis of the organizational core values of the world’s most admired companies. Knowl Process Manag. 2014;21(3):159–166. doi:10.1002/kpm.1447

90. Gouthier MHJ, Rhein M. Organizational pride and its positive effects on employee behavior. J Serv Manag. 2011;22(5):633–649. doi:10.1108/09564231111174988

91. Reizer A, Brender-Ilan Y, Sheaffer Z. Employee motivation, emotions, and performance: a longitudinal diary study. J Manag Psychol. 2019;34:415–428. doi:10.1108/JMP-07-2018-0299

92. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

93. Englander ZA, Haidt J, Morris JP. Neural basis of moral elevation demonstrated through inter-subject synchronization of cortical activity during free-viewing. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039384

94. Kong L, Sial MS, Ahmad N, et al. CSR as a potential motivator to shape employees’ view towards nature for a sustainable workplace environment. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1499. doi:10.3390/su13031499

95. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, Mahmood A, et al. Corporate social responsibility at the micro-level as a “new organizational value” for sustainability: are females more aligned towards it? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):2165. doi:10.3390/ijerph18042165

96. IQAir. Air quality in Pakistan; 2020. Available from: https://www.iqair.com/us/pakistan.

97. Deng Y, Cherian J, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Samad S. Conceptualizing the role of target-specific environmental transformational leadership between corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors of hospital employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3565. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063565

98. Xu L, Mohammad SJ, Nawaz N, Samad S, Ahmad N, Comite U. The role of CSR for de-carbonization of hospitality sector through employees: a leadership perspective. Sustainability. 2022;14(9):5365. doi:10.3390/su14095365

99. Ahmad N, Mahmood A, Han H, et al. Sustainability as a “new normal” for modern businesses: are SMEs of Pakistan ready to adopt it? Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1944. doi:10.3390/su13041944

100. United Nations. Pakistan Life Expectancy 1950–2022. USA: United Nations; 2020. Available from: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/PAK/pakistan/life-expectancy.

101. United Nations. World population prospects. New York City, USA; 2022. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/.

102. Wasay M, Malik A. A new health care model for Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69:5.

103. Adnan M, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Khalique M, Naveed RT, Han H. Impact of substantive staging and communicative staging of sustainable servicescape on behavioral intentions of hotel customers through overall perceived image: a case of boutique hotels. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9123. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179123

104. Awan K, Ahmad N, Naveed RT, Scholz M, Adnan M, Han H. The impact of work–family enrichment on subjective career success through job engagement: a case of banking sector. Sustainability. 2021;13(16):8872. doi:10.3390/su13168872

105. Han H, Al-Ansi A, Chua B-L, et al. Reconciling civilizations: eliciting residents’ attitude and behaviours for international Muslim tourism and development. Curr Issues Tour. 2022;2022:1–19.

106. Peng J, Samad S, Comite U, et al. Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ Energy-specific pro-environmental behavior: evidence from healthcare sector of a developing economy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7641. doi:10.3390/ijerph19137641

107. Chen J, Ghardallou W, Comite U, et al. Managing hospital employees’ burnout through transformational leadership: the role of resilience, role clarity, and intrinsic motivation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10941. doi:10.3390/ijerph191710941

108. Guan X, Ahmad N, Sial MS, Cherian J, Han H. CSR and organizational performance: the role of pro‐environmental behavior and personal values. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2022. doi:10.1002/csr.2381

109. Fu Q, Cherian J, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Samad S, Comite U. An inclusive leadership framework to foster employee creativity in the healthcare sector: the role of psychological safety and polychronicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4519. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084519

110. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Han H, Ariza-Montes A, Vega-Muñoz A. Fostering advocacy behavior of employees: a corporate social responsibility perspective from the hospitality sector. Front Psychol. 2022;2022:13.

111. Ullah Z, Shah NA, Khan SS, Ahmad N, Scholz M. Mapping institutional interventions to mitigate suicides: a study of causes and prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10880. doi:10.3390/ijerph182010880

112. Alam T, Ullah Z, AlDhaen FS, AlDhaen E, Ahmad N, Scholz M. Towards explaining knowledge hiding through relationship conflict, frustration, and irritability: the case of public sector teaching hospitals. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12598. doi:10.3390/su132212598

113. Turker D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: a scale development study. J Bus Ethics. 2009;85(4):411–427. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9780-6

114. Molnár E, Mahmood A, Ahmad N, Ikram A, Murtaza SA. The interplay between corporate social responsibility at employee level, ethical leadership, quality of work life and employee pro-environmental behavior: the case of healthcare organizations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4521. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094521

115. Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):192–207. doi:10.1080/02678370500297720

116. Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46(2):137–155. doi:10.1023/A:1006824100041

117. Sweetman J, Spears R, Livingstone AG, Manstead AS. Admiration regulates social hierarchy: antecedents, dispositions, and effects on intergroup behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49(3):534–542. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.007

118. Lilius JM, Worline MC, Maitlis S, Kanov J, Dutton JE, Frost P. The contours and consequences of compassion at work. J Organ Behav. 2008;29(2):193–218. doi:10.1002/job.508

119. Daniel S. A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models 2010; 2022.

120. Ahmad N, Naveed RT, Scholz M, Irfan M, Usman M, Ahmad I. CSR communication through social media: a litmus test for banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):2319. doi:10.3390/su13042319

121. Gupta S, Nawaz N, Tripathi A, Muneer S, Ahmad N. Using social media as a medium for CSR communication, to induce consumer–brand relationship in the banking sector of a developing economy. Sustainability. 2021;13(7):3700. doi:10.3390/su13073700

122. Ahmad N, Mahmood A, Ariza-Montes A, et al. Sustainable businesses speak to the heart of consumers: looking at sustainability with a marketing lens to reap banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability. 2021;13(7):3828. doi:10.3390/su13073828

123. Gupta S, Nawaz N, Alfalah AA, Naveed RT, Muneer S, Ahmad N. The relationship of CSR communication on social media with consumer purchase intention and brand admiration. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. 2021;16(5):1217–1230. doi:10.3390/jtaer16050068

124. Ullah Z, Naveed RT, Rehman AU, et al. Towards the development of sustainable tourism in Pakistan: a study of the role of tour operators. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):4902. doi:10.3390/su13094902

125. Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Naveed RT, et al. Towards making an invisible diversity visible: a study of socially structured barriers for purple collar employees in the workplace. Sustainability. 2021;13(16):9322. doi:10.3390/su13169322

126. Zhang D, Mahmood A, Ariza-Montes A, et al. Exploring the impact of corporate social responsibility communication through social media on banking customer e-wom and loyalty in times of crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4739. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094739

127. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

128. Ahmad N, Scholz M, AlDhaen E, Ullah Z, Scholz P. Improving Firm’s economic and environmental performance Through the sustainable and innovative environment: evidence from an emerging economy. Front Psychol. 2021;12:651394. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651394

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.