Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

Fear of failure among a sample of Jordanian undergraduate students

Authors Alkhazaleh Z, Mahasneh AM

Received 15 September 2015

Accepted for publication 28 January 2016

Published 31 March 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 53—60

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S96384

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Ziad M Alkhazaleh, Ahmad M Mahasneh

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education Sciences, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

Background: Fear of failure (FoF) is the motivation to avoid failure in achievement tests, and involves cognitive, behavioral, and emotional experiences.

Aims: The primary purpose of this study was to determine the level of FoF among students at The Hashemite University, Jordan. We were also interested in identifying the difference in the level of FoF between the sexes, the academic level, and grade-point average (GPA).

Method: A total of 548 students participated in the study by completing the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory. Descriptive statistics (mean and SD), independent sample t-test, and one-way analysis of variance were used to analyze the data collected.

Results: The results indicated the overall mean FoF to be –0.34. There were also significant differences between male and female students' level of fear in experiencing shame and embarrassment. Significant differences were found between the four academic level groups in the following fear categories: experiencing shame and embarrassment, important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others. The results also showed significant differences between the GPA level groups in the following fear categories: experiencing shame and embarrassment, diminishing of one's self-esteem, having an uncertain future, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others.

Conclusion: FoF may be an important consideration when trying to understand student behavior in the university. Moreover, the level of FoF differs between sexes, academic levels, and GPA levels.

Keywords: fear, fear of failure, Jordanian students

Introduction

Fear of failure (FoF) among students in higher education is an important topic for psychologists and counselors who work on college campuses. The concept of FoF has been examined from various perspectives in the literature of psychodynamics, encompassing inhibitions, underachievement, and intellectual pursuits. Baker1 theorized that neurotic family relationships and attitudes toward the child’s poor performance played a causal role in the development of FoF.

As defined in the studies by Elliot and Sheldon2 and by Elliot3, the intrinsic energy of FoF may be the motivation for evading a negative possibility. In early theories of achievement motivation, FoF was defined as failure-avoidance motivation to escape the feelings of shame and humiliation engendered by failure. Thus, FoF was considered a one-dimensional personality trait in the concept of an anticipatory capacity regarding the negative effect in evaluative or achievement conditions. Two achievement orientations were posited: guiding the individual toward failure avoidance and positive guidance toward successful achievement. In so doing, FoF and the need for achievement were conceived as two distinct motivational entities.

McClelland4 has stated that the typical age at which failure avoidance motivation develops is between 5 years and 9 years. According to Conroy et al,5,6 while contemporary theories also view FoF as a trait, contrary to the early concept of separate motivational entities, the modern concept is of a multidimensional construct that is hierarchical in nature, motivating failure avoidance due to fear of its many unpleasant consequences.

Research supports the proposal that FoF is caused by the perception of aversive consequences,5–7 while studies by Lazarus showed that fear and anxiety were elicited by the expectation of threatening consequences. The threat situation is created by confrontation with a provocation that will compromise personal values and aspirations.8,9

Heckhausen10 states that personal perception and definition of an academic failure relate directly to individual FoF, which emerges not only from an individual’s self-evaluation but also from the evaluation of the opinion of others as a result of the failure.

There are five reasons for people to avoid failure: First is the expectation of feeling ashamed due to failure. Second, some people feel that failure creates a self-critical condition of mind wherein their intelligence and talent are assessed negatively. Third, people’s plans for the future can be negatively affected. Fourth, it is believed by some that success is the most important criterion for their parents, teachers, or peers and that failure will result in the loss of their esteem. The last reason is the fear that failure may not only cause the loss of regard and probation of people important to them but also distress them.6,11,12

Researchers recognize that the models of FoF and achievement motivation became popular areas of study during the 20th and 21st centuries.13 This was supported by Shaver,14 who noted that the increased incidence of individuals suffering from FoF stemmed from the pressure to achieve, whether academically or in the career structure. Achievement motivation research by Atkinson15,16 and his Need Achievement Theory originated the psychological theory regarding FoF throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Atkinson15 defined FoF as “an avoidant motive which was aroused by debilitating anxiety”.

The definition of FoF given by Conroy et al,13 “a tendency to appraise threat and feel anxious during situations that involve the possibility of failing”, can be divided into two distinct general categories as described by Golden17 as fears pertaining to interpersonal failure and educational or academic failure, though it is often the case that an individual fearing failure in the workplace may also fear failure in his or her personal life.

A study by Covington and Omelich18 also found that those individuals fearing failure suffered from a general lack of confidence in their ability to succeed in any domain, while according to Shultz,19 FoF in a particular task or endeavor is often accompanied by the concern associated with unpleasant negative consequences. As described by Conroy et al,20 the individual is consequently motivated to avoid anticipated failure and its attendant humiliation and shame.

McGregor21 considers the fear of shame as a strong contributory factor to FoF; shame behavior being avoidant in nature. Lazarus22 described it as negative personal censure, and Lewis23 defined this self-reproach as a reaction to failure in achieving self-set standards. McGregor21 agrees that lack of success may instigate negative feelings of incompetence and shame.

Previous research has found that parental reactions are the likely causative factor in childhood shame related to failure.21,24 According to researchers, lack of self-confidence and low self-esteem, in association with low risk-taking ability, have a direct correlation with FoF.2,25,26

Lazarus, referring to the cognitive motivational relational theory of emotion, postulates that the perception of a threatening indication of failure necessitates assessment (primary appraisal process) of the extent to which their goal-achievement ability will be affected. This appraisal will lead to determining the level and extent of impact by the perceived threat and an evaluation of the relative importance of achieving those goals.8,22

Lazarus elaborates on this perspective by stating that FoF and the subsequent performance failure demand an evaluation of the resultant threat to the achievement of personally significant goals. This act of appraisal instigates the aversive cognitive beliefs and schemas related to the consequences of failure or lack of the desired level of success, thus activating fear.8,22

Researchers identify five beliefs related to the consequence of failure associated with threat assessment, which in their view constitute the basis of five FoFs: experiencing shame and embarrassment, important others losing interest, devaluing one’s self-esteem, anxiety regarding an uncertain future, and disappointing and distressing significant others.6

Conroy and Elliot reiterate that many individuals become fearful and apprehensive in evaluative situations since they associate failure with aversive consequences, thus being a learned dispositional tendency representing FoF. The level or strength of belief concerning the probability of failure-related aversive consequences differs between individuals, as does the fear level.12

Young et al27 accordingly view FoF-oriented individuals to experience fear and anxiety in achievement failure as a schema or learned personality trait. Conroy11 reported that consequences of such fear and anxiety induced a range of negative psychological and physical effects including anxiety, worry, shame, depression, and eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia, with those individuals frequently required to perform high-achievement tasks being particularly susceptible.

Covington28 and Elliot and Church,29 studying education-related occurrences, found that in all levels of ability, whether actual or perceived, FoF was prominent in both sexes. As concluded by Elliot and Harackiewicz30 and Elliot and McGregor,31 the adoption of performance-avoidance goals is reinforced by FoF resulting in anxiety, diminished performance, and loss of interest and motivation, which can ultimately lead to student dropout.

Purpose of the study

To our knowledge, no study has attempted to determine the level of FoF in a sample of undergraduate students in a Jordanian University. The intent of the current study was to determine FoF among a sample of students at The Hashemite University (HU), Jordan. We were also interested in identifying the difference in the level of FoF between the sexes, academic level, and grade-point average (GPA). The following research questions were pursued in this study: 1) Determine the level of FoF among students at HU. 2) Determine the differences in students’ FoF based on sex, academic level, and GPA.

Method

Participants

The study population consisted of all undergraduate students at HU (N=29,643) in the second semester of the academic year 2014–2015. Six hundred undergraduate students were invited to participate, and 548 returned the questionnaire. The participants were selected based on the purposive sample technique from among students enrolled in introductory psychology courses at HU. The sample comprised of 225 men (41%) and 323 women (59%). With regard to academic level, 153 were in the first year (28%), 130 in the second year (24%), 136 in the third year (25%), and 129 in the fourth year (23%). GPA ranged from excellent (3.50–4.0) (48, 9%), very good (3.0–3.49) (220, 40%), good (2.50–2.99) (208, 38%), and acceptable (2.0–2.49) (72, 13%). The average age of the participants was 20 years (SD =0.97).

The purpose of the current study and it’s procedures undertaken were explained to all the participants. All participants questions were fully answered. All participants understood the explanations and gave written informed consent. The current study was approved by The Hashemite University Human Ethics Committee.

Materials

FoF was assessed using the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory (PFAI), which consists of 25 items measuring belief associated with aversive consequences of failure.6 Responses to the PFAI are ranked on a five-point scale ranging from –2 to +2. PFAI has five subscales encompassing fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment (seven items, eg, “When I am not succeeding, I am less valuable than when I succeed”), fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem (four items, eg, “When I am failing, it is often because I am not smart enough to perform successfully”), fear of having an uncertain future (four items, eg, “When I am failing, my future seems uncertain”), fear of important others losing interest (five items, eg, “When I am not succeeding, people are less interested in me”), and fear of upsetting important others (five items, eg, “When I am failing, it upsets important others”). Construct validity evidence has been found for this inventory.6,32 Internal consistency estimates ranged from 0.69 to 0.90.32

To ensure validity and consistency of the PFAI scale in this study, it was translated into Arabic by two bilingual (English/Arabic) faculty members and was further subjected to rigorous forward–backward translation verification. This process confirmed that the Arabic version of items and constructs in the translated version were synonymous with the original English version. As a further safeguard toward ensuring equivalency, staff members of three faculties from HU, none of whom participated in the forward–backward translation process, conducted an independent evaluation of the original English and the back-translated versions.

The Cronbach-α results were as follows: 0.82, 0.72, 0.69, 0.70, and 0.67, respectively, for fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment, fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem, fear of having an uncertain future, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others.

Data collection and analysis

The study was conducted during the second semester of the academic year 2014–2015. The researchers selected four courses of the university optional requirement during class sessions, and explained the purpose and format of the study. The participants were asked to complete the demographic data in the questionnaire before proceeding to give their response to items in the PFAI. They were then asked to complete the PFAI by reading each item and then answering it based on their experience.

Procedures for the statistical analysis were discussed based on the research questions. Research question 1 was to determine the level of FoF among undergraduate students at HU. Descriptive statistics, mean and SD, for the five dimensions of PFAI were used to answer this question. Research question 2 was used to determine the differences in students’ FoF based on their sex, academic level, and GPA. In the case of sex, an independent sample t-test was used, whereas in the case of academic level and GPA, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. The SPSS statistical package Version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to carry out the analysis. The α-level was set at 0.05 a priori.

Results

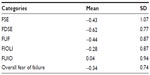

The aim of research question 1 was to determine the level of FoF among students at HU. Descriptive statistics, mean and SD, were used to achieve this objective. Table 1 shows that the mean for fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment is –0.43, fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem is –0.62, fear of having an uncertain future is –0.44, fear of important others losing interest is –0.28, and fear of upsetting important others is 0.04. The overall mean of FoF was –0.34.

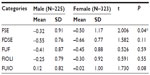

The aim of research question 2 was to determine whether significant differences existed in FoF based on the selected characteristics of sex, academic level, and GPA. An independent sample t-test was used to examine the difference in mean between male and female students. However, one-way ANOVA was used to identify whether the variances of the levels for the four groups of academics and GPA were equal or showed statistically significant differences. Table 2 shows that there were significant differences at the 0.05 α-level between male and female students’ level of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment (t=2.006, P=0.04), whereas no significant differences were evident between male and female students’ level of fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem, fear of having an uncertain future, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others.

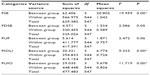

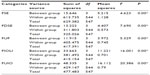

Table 3 shows that there were significant differences at the 0.05 α-level between the four academic level groups in the level of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment (F=19.959, P=0.00), fear of important others losing interest (F=9.333, P=0.00), and fear of upsetting important others (F=11.719, P=0.00), whereas there were no significant differences between the four groups in the level of fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem and fear of having an uncertain future.

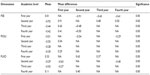

Using the Scheffe comparison test, differences were detected between the four academic level groups in the level of FoF. Table 4 shows the differences between first-year academic level and the second-, third-, and fourth-year academic levels in the fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others.

Table 5 shows that there were significant differences at the 0.05 α-level between the GPA level groups in the level of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment (F=4.623, P=0.00), fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem (F=7.690, P=0.00), fear of having an uncertain future (F=5.329, P=0.00), fear of important others losing interest (F=16.001, P=0.00), and fear of upsetting important others (F=20.386, P=0.00).

Using the Scheffe comparison test, differences were detected between four GPA level groups in the level of FoF. Table 6 shows the differences between good GPA level and acceptable GPA level in the fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment and fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem. Also, Table 6 shows the differences between acceptable GPA level and excellent, very good, and good GPA levels in fear of having an uncertain future, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate FoF in university students. The sample consisted of 548 undergraduate students at HU. The independent variables investigated were sex, academic level, and GPA. The dependent variable was FoF. Descriptive statistical analysis of the study objectives were the mean, SD, independent sample t-test, and one-way ANOVA. The results of the study indicate that the mean for overall FoF was –0.34. This result indicates that the level of FoF among the undergraduate students at HU was low. The shift from high school to university is a major life transition for young adults. This transition period is a change in emerging adults to meet the personal demands of the new academic and social environment. In others words, university life requires young adults to learn to cope with various challenges and take actions to integrate into the university’s academic and social life, meet academic demands, establish new friendship networks, become more independent, and take responsibility in their personal lives, and for these reasons the level of FoF becomes low.

Results of the current study clearly indicate a significantly higher level of the fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment among the female students than their male counterparts. This indicates that female students who experience failure early in life may tend to give up more easily than their male peers. The shame and embarrassment surrounding failure may be overwhelming, and since females tend to be cooperative rather than competitive, they may decide that trying again is not worth the cost involved.

These findings support those of previous studies, which noted that being prone to feelings of shame precedes FoF in women, who also evidenced higher levels of achievement guilt than men. In light of these findings, the current study is significant for female students.12,33

Rothblum found that, when females believe achievement to be a significant factor that could impact a relationship, they report higher levels of FoF. Females therefore, are more worried than males by the prospect of failure having a negative impact on a relationship and causing the other person to lose interest.34

Stein and Bailey found female students to be more anxious about academic failures than men and also experienced a higher anxiety level about tests and examinations. The researchers also noted that females are more deeply affected by early failure experiences than are males, and this may encourage a tendency in women to give up more easily than their male peers. Females are often overwhelmed by the shame and embarrassment of failure, and since their tendency is to be cooperative rather than competitive, the risk of further failure may deter them from trying again.35 Given that previous studies have identified the central motivating emotion to be the fear of shame, the findings of this study make a significant contribution to aspects of future practice regarding female students.36

Results of the current study show that there were significant differences between the four academic level groups in the level of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others. This result indicates that FoF for students in the first academic level is more than that in the second, third, and fourth academic levels. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that incoming college freshman are in need of and will benefit from counseling and student affairs involvement, both in overcoming feelings of inadequacy in an unfamiliar academic setting and reducing FoF.

These conclusions may shed light on the high dropout risk of first-generation college students after only 1 year. In their research, Bui37 and Cox38 concluded that first-generation students are typically less self-confident, doubting their ability to succeed academically.

These results support studies that found that first-generation freshman showed lower self-esteem and self-confidence, although the present findings suggest that first-generation students do show improved academic self-efficacy and reduced FoF with each consecutive year in college.39

Results of the current study also showed that there were significant differences between the GPA level groups in the level of fear experiencing shame and embarrassment, fear of devaluing one’s self-esteem, fear of having an uncertain future, fear of important others losing interest, and fear of upsetting important others. This result indicates that students who experience higher levels of FoF secure lower academic GPA than their counterparts who are more academically self-efficacious and less anxious about failure.

These results support the study by Stuart40 investigating the correlation between FoF and academic GPA, which concluded that students exhibiting higher levels of FoF had lower GPA than students with higher academic confidence and lower failure anxiety.

Implications

The findings of the current study in highlighting the role of FoF in student self-efficacy and academic achievement have implications for the faculty, staff, and counselors. We suggest that, in order to help vulnerable students overcome these fears, implementing a plan of intervention could be productive. Such a plan would be structured on a strategy of both individual and group counseling, focusing on the multidimensional aspects of FoF. Future research will investigate the relationship between FoF and self-regulated learning.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study suggest that the mean level of FoF among undergraduate students at HU was low. Further, this study identified differences in students’ FoF based on sex, academic level, and GPA, and showed a higher level for fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment among the female students than their male counterparts. FoF for students in the first academic level is more than that of the second, third, and fourth academic level. Students who experience higher levels of FoF secure lower academic GPA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Baker HS. The conquering hero quits: narcissistic factors in underachievement and failure. Am J Psychother. 1979;33:418–427. | |

Elliot AJ, Sheldon KM. Avoidance achievement motivation: a personal goals analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:171–185. | |

Elliot AJ. Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educ Psychol. 1999;34:149–169. | |

McClelland DC. The importance of early learning in the formation of motives. In: Atkinson JW, editor. Motives in Fantasy, Action, and Society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand; 1958:437–452. | |

Conroy DE, Poczwardowski A, Henschen KP. Evaluative criteria and consequences associated with failure and success for elite athletes and performing artists. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2001;13:300–322. | |

Conroy DE, Willow JP, Metzler JN. Multidimensional fear of failure measurement: the performance failure appraisal inventory. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2002;14:76–90. | |

Birney RC, Burdick H, Teevan RC. Fear of Failure. New York, NY: American Book Company; 1969. | |

Lazarus RS. Stress and Emotions: A New Synthesis. London: Free Association Books; 1999. | |

Lazarus RS. How emotions influence performance in competitive sports. Sport Psychol. 2000;14:229–252. | |

Heckhausen H. Achievement motivation and its constructs: a cognitive model. Motiv Emot. 1997;1(4):283–329. | |

Conroy DE. Progress in the development of a multidimensional measure of fear of failure: the performance failure appraisal inventory (PFAI). Anxiety Stress Coping. 2001;14:431–452. | |

Conroy DE, Elliot AJ. Fear of failure and achievement goals in sport: addressing the issue of the chicken and the egg. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2004;17(3):271–285. | |

Conroy DE, Metzler JN, Hofer SM. Factorial Invariance and latent mean stability of performance failure appraisals. Struct Equ Modeling. 2003;10(3):401–422. | |

Shaver P. Questions concerning fear of success and its conceptual relatives. Sex Roles. 1976;2:305–320. | |

Atkinson JW. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol Rev. 1957;64:359–372. | |

Atkinson JW. An Introduction to Motivation. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand; 1964. | |

Golden C. I know this is stupid, but…: Or, some thoughts on why female students fear failure and not success. Women Ther. 1988;6:41–49. | |

Covington MV, Omelich CE. Need achievement revisited: verification of Atkinson’s original 2x2 model. In: Spielberg CD, Sarason IG, Kulesar Z, Heek GL, editors. Stress and Emotion: Anxiety, Anger, Curiosity. New York, NY: Hemisphere; 1991:85–105. | |

Shultz, T. (1999). Behavioral Tendencies of High Fear of Failure Individuals in Variable Situational Conditions [Doctoral dissertation]. New York: The City University of New York; 1999. Retrieved from UMI. (UMI Number: 9917698). | |

Conroy DE, Kaye MP, Fifer AM. Cognitive links between fear of failure and perfectionism. J Ration-Emotive Cognit-Behav Ther. 2007;25:237–253. | |

McGregor HA. The shame of failure: exploring the relationship between fear of failure and shame. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester, 2003). Diss Abstr Int. 2003;64:1942. | |

Lazarus RS. Emotion and Adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991. | |

Lewis M, editor. Shame: The Exposed Self. New York (NY): The Free Press; 1992. | |

Andrews B. Shame and childhood abuse. In: Gilbert P, Andrews B, editors. Shame: Interpersonal Behavior, Psychopathology and Culture Series in Affective Science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:176–190. | |

Martin AJ, Marsh HW. Fear of failure: friend or foe? Aust Psychol. 2003;38:31–38. | |

Sherman JA. Achievement related fears: gender roles and individual dynamics. Women Ther. 1988;6:97–105. | |

Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. | |

Covington MV. Making the Grade: A Self-Worth Perspective on Motivation and School Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. | |

Elliot AJ, Church MA. A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:218–232. | |

Elliot AJ, Harackiewicz JM. Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: a meditational analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:968–980. | |

Elliot A, McGregor H. A 2*2 achievement goal framework. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80:501–519. | |

Conroy DE, Metzler JN. Temporal stability of performance failure appraisal inventory items. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2003;7(4):243–261. | |

Thompson T, Sharp J, Alexander J. Assessing the psychometric properties of a scenario-based measure of achievement guilt and shame. Educ Psychol. 2008;28(4):373–395. | |

Rothblum ED. Fear of failure: the psychodynamic, need achievement, fear of success, and procrastation models. In: Leitenberg H, editor. Handbook of Social and Evaluation Anxiety. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1990:497–535. | |

Stein A, Bailey MM. The socialization of achievement orientation in females. Psychol Bull. 1973;80:345–366. | |

McGregor HA, Elliot AJ. The shame of failure: examining the link between fear of failure and shame. Soc Personal Soc Psychol. 2005;31(2):218–231. | |

Bui KV. First-generation college students at a four-year university: background characteristics, reasons for pursuing high education, and first-year experiences. Coll Stud J. 2002;36(1):3–11. | |

Cox R. It was just that I was afraid: promoting success by addressing student’s fear of failure. Commun College Rev. 2009;37(1):52–80. | |

Nunez A, Cuccaro-Alamin S. First-Generation Students: Undergraduates Whose Parents Never Enrolled in Postsecondary Education. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office: (NCES 1998-082) U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 1998. | |

Stuart EM. The Relationship of Fear of Failure, Procrastination and Self-Efficacy to Academic Success in College for First and Non First-Generation Students in a Private Non-Selective Institution [Doctoral dissertation]. Tuscaloosa, AL; University of Alabama; 2013. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.