Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 15

Factors Affecting Payment Compliance of the Indonesia National Health Insurance Participants

Authors Sunjaya DK , Herawati DMD , Sihaloho ED , Hardiawan D , Relaksana R, Siregar AYM

Received 13 November 2021

Accepted for publication 7 February 2022

Published 22 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 277—288

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S347823

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mecit Can Emre Simsekler

Deni Kurniadi Sunjaya,1 Dewi Marhaeni Diah Herawati,1 Estro Dariatno Sihaloho,2 Donny Hardiawan,2 Riki Relaksana,2 Adiatma Yudistira Manogar Siregar2

1Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; 2Center for Economics and Development Studies, Department of Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

Correspondence: Deni Kurniadi Sunjaya, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jalan Eyckman No. 38, Bandung, Indonesia, Tel +62 82218893543, Email [email protected]

Background: The study aims to explore factors that affect the compliance of Indonesia National Health Insurance (INHI) in paying the premiums.

Methods: The study design was qualitative with grounded theory research approach and constructivism paradigm. The study was conducted in 2018 and carried out for 3 months. We recruited 22 respondents from four different cities/districts. Triangulation was carried out through 26 informants from various stakeholders. Data were analyzed through coding, categorizing and pattern matching to obtain substantive theory.

Results: The resulting substantive theory consists of 6 constructs and 14 categories. Compliance with paying insurance premium depends on the intention to pay for contribution. Meanwhile, the intention to pay is related to internal and external factors of INHI participants. To improve payment contribution of independent participants, INHI program has to pay attention for factors originating internally from the participants themselves (understanding of INHI program, financial ability and self-attitude) and also externally such as operational system and the quality of health care.

Conclusion: Compliance of paying insurance premium is related to internal and external factors of participants. Thus, interventions to improve compliance to pay premium should take these factors into account, and not merely on increasing the knowledge of participants.

Keywords: independent membership, social health insurance, premium contribution, compliance

Introduction

Costs in health care are often a barrier for people with illness to access health services and create disruption in their daily lives and well-being. Social health insurance (SHI) aims to increase access to health services for everyone or act as a universal health coverage, aiming to realize the improvement of individual and community health and welfare status.

Since 2014, Indonesia has reformed the health financing system through Indonesia National Health Insurance (INHI) policy or what is known as Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN). JKN is a compulsory and centralized social health insurance with one operator for the whole country. Health insurance is an important strategy for the protection of household finances,1,2 especially in light of the household health-care spending that exceeds 40% of its income after deducting expenses for subsistence needs.3 Health insurance increases the utilization of health services, protects the poor from high care costs and provides financial security, reduces out of pocket financial expenditures, and promotes the use of drugs that are more cost effective.4–6

JKN management is carried out by a third party, an agency called Social Security Administrative Body for Health (SSABH) or Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial Kesehatan (BPJSK), supervised directly by the President of Indonesia. Patients receive full coverage for the treatment of most illnesses.7,8 After 4 years of implementation, by 2019 the number of JKN memberships reached 83.6% (around 220 million people) of the total population of Indonesia.9

The participants are classified into two types: premium assistance beneficiaries (PAB, the poor and near poor) and non-premium assistance beneficiaries (NPAB). The NPAB includes: primary workers (those having “steady and continuing labor force attachment”); secondary workers (“those who have had, are having, or are about to have a temporary labor force attachment”); and non-workers (“those who have not had and are not likely to have any labor force attachment”). Premium for the poor (and near poor) is funded by the government and regional governments.

Secondary workers and non-workers within the non-premium assistance beneficiary group pay the premium independently as long as they are members and are called independent participants, while the premium of primary workers is paid by the respective workplace.9–11 It is difficult for BPJSK to control the group that does not have an insurer (responsible institution) for payment of contributions, when it is borne by themselves.

Independent participants are expected to participate in reducing the financial burden of government in the spirit of mutual cooperation.12,13 Community participation is important in program sustainability. Although independent participants shared around 14% of the total JKN participants in 2017, 45.71% of them failed to pay the premium regularly each month.14 This is one of the causes of the deficit problem faced by the JKN program.9

The reasons for participants failing to pay contributions varied significantly. In the context of JKN, financial hardship, health-care utilization, number of household member, and having other insurance(s) are correlated with independent contributors’ premium payment, while participant compliance will increase if professional health-care services are available.9

Compliance in paying contribution is very important for the sustainability of JKN. The implementation of the JKN, which has been running for 4 years and experiences deficit, needs to be supported by an in-depth understanding of the incomplete payment of the contribution. The purpose of this study is to explore factors that affect independent JKN participants in compliance with paying the premiums.

Materials and Methods

This research used the Ability, Opportunity and Motivation (AOM) theory as a theoretical proposition.15,16 The AMO framework is used as a basic concept of psychology which states that motivation is considered an incentive for behavior, and ability is an important skill toward behavior. While opportunity is a contextual and situational constraint that is relevant to a behaviour.17

Motivation is a complex concept, where the level and type of motivation are important aspects for someone to consider something and to energize their behavior in pursuing a goal.18,19 Intrinsic motivation as inherent behavior in a person is based on the urge to act that come from themselves, and they enjoy the behavior because there are challenges to complete tasks.20 Extrinsic motivation as a type of motivation is controlled by externalities that are not part of a person’s activity or behaviour.18

Ability consists of individual knowledge and skills. A person may have the intention or motivation to behave according to social rules, but such behavior will not occur if a person’s abilities are inadequate. Inadequate knowledge and skills will be barriers for someone to change their behaviour.21 In addition, opportunities can improve compliance by increasing motivation and ability.22

Research Design

The design of this study is qualitative study23,24 with grounded theory research approach25,26 and constructivism paradigm27. Grounded theory was chosen to be able to produce substantive theory through the steps of coding, categorizing, pattern matching and theorizing.25,28 The constructivism paradigm is used because researchers are directly involved in building ideas, collecting data, processing and analyzing them.

Researchers are intensely involved in building concepts and theories through understanding, interpreting and interpreting data. We opt to produce substantive theory as it is built and constructed solely from the data (grounded) that comes only from this single study. Aspects of compliance with paying dues can be identified and hypotheses can be built. So that the Grounded theory function with this constructivism approach can prepare the basis for further research.

Study Context

Indonesia consists of more than 17 thousand islands with 8 large islands. Java as one of the largest islands is inhabited by 80% of the population. West Java is the province with the largest number of population (46 million in 2018). This province is divided into 27 districts/cities. The largest ethnic groups are Sundanese, followed by Javanese and various other ethnic groups. Most of the population has middle school level education and illiteracy still exists in 604,378 of the population.

Indonesia as a democratic country has adopted a decentralized political system since year 2000. Health services are provided by the Government and the private sectors. For public health services, there are hospitals owned by the central and local governments, and Community Health Centers (CHC), or Puskesmas, as primary health services facility.

Subject

The study population was Secondary Worker participants who either failed or obey to pay the premiums. We selected purposively two district and two cities which have the highest number of not complying participants.

The inclusion criteria were secondary worker participants, in arrears to pay contributions of more than 3 months, and residence in four selected districts/cities. We collected the list of subjects of participants who do not comply from BPJSK offices in respective cities/regencies to be included in the research. We did random sampling from the list and go to the selected subjects at his/her places to collect data. Our exclusion criteria were those who have never paid dues and refused to participate, which were none during the data collection.

Using theoretical sampling, the number of the main subjects that were successfully recruited were 22 respondents until there was saturation.26,29 For triangulation,30 we recruited 26 respondents purposively from: BPJSK offices, the Social Service offices, the Health Service Offices, farmers, fishermen, and small trader associations.

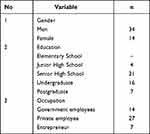

Secondary worker respondents (hereinafter abbreviated as participant) were located at four sites: Cirebon City, Sukabumi City, Pangandaran District, and Garut District of West Java Province. Respondents represented stakeholders from BPJSK and the Health Service and Social Service were taken from cities/districts as well. Fishermen associations were taken from Pangandaran District, farmer associations were from Garut District, and merchant associations were from Cirebon City. The selection of cities and respondents for triangulation was done purposively. Overall, the number of participants of the study was 48 people (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristic of Respondents |

Ethical Considerations

This research is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has obtained ethical clearance from the Universitas Padjadjaran Ethical Committee, No. 780/UN6.KEP/EC/2018. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participating in this study, and informants were registered under pseudonyms. The informed consent also included the anonymity in presenting subjects’ responses in the manuscript.

Data Collection

The study was conducted in 2018 and carried out for 3 months. Data collection was carried out by face-to-face in-depth interviews. Because the regencies/cities are far apart, the researchers were divided into these 4 regencies. These researchers have been standardized before going to the field. Researchers in each district/city first visited the BPJSK Office to conduct a desk recruitment randomization of prospective respondents from the available data. Then, choose the participant JKN respondents who will be visited first.

The guidance for interview refers to the AMO’s theoretical proposition which are Ability, Motivation, Opportunity.15 We explored this construct and its indicators as mentioned in the background. Interviews for INHI were conducted at the respondent’s residence. As for stakeholders in the respondent’s workplace. The interview time varies from 1 to 2 hours. Interviews were recorded using a recording device. Each respondent was only interviewed for one round.

On the same day, transcription was carried out. Transcripts are sent via the cloud, so that researchers in different districts/cities can know each other’s transcription content. Interviews done by researchers were directly analyzed before moving to other respondents. The lead researcher, apart from direct interviews, controlled data collection and transcription activities and initiated the first and subsequent analysis of data collected from cloud-based storage. As such, we were sure to produce saturated codes and categories from these respondents. Triangulation methods were used to ensure trustworthiness and study rigorousness. We interviewed stakeholders’ respondents linked to the result of main respondent (secondary worker) perceptions.

Data Analysis

As said earlier, all the results of the interviews were first transcribed. Transcription was followed by data reduction, coding, categorization, theme development, pattern matching, concept mapping and theory development. We conducted constant comparative analysis since the collection of the first data and between sites.26,31–34 by completing the concept map.

We guarantee trustworthiness both in data collection and data analysis. To maintain credibility and rigorousness of the study, data sources were triangulated. Peer debriefing/review was carried out together with the research team since the data collection phase in the field.

Results

The substantive theories that we have found are as follows: the compliance in contribution payment is related to the intention to pay for contribution, understanding of INHI, financial ability, self-attitude, the operational system and quality of services both from health-care services and BPJSK offices. This is the hypothesis built in our research as the end result of our analysis using grounded theory method. The substantive theory developed in this research (Figure 1) is completely different from the theoretical propositions on which the previous theory was based on (the AMO).

|

Figure 1 Substantive theory: factors affecting compliance of INHI participants. |

Descriptions of these factors are presented below. Basically, these factors come from the internal and external factors of participants. Internal factors include dissemination information, understanding of risk, understanding of the benefit packages, ability to pay contribution, ability to bear cost, income regularity, personal beliefs, social norms, family and society encouragement.

External factors can come from the operational system and the quality of health services. The operational system includes access, penalty, local regulation, portability and local government involvement. Quality of health services consists of waiting time and discrimination (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Themes and Categories of Factors Affecting Premium Paying Compliance |

Theme 1. Understanding of JKN

Dissemination of Information

The dissemination of information on JKN program from the local government was felt to be lacking. Some misunderstood that the JKN premium is paid by the government, which led to the assumption that JKN is free. Information is not obtained in depth, such as matters relating to membership, contribution, mandatory insurance, obligation to pay premiums and others. However, for people who have a good level of education and financially capable, they obtained information through television and other media. Thus, many economically better off people who participate in private insurance decide to switch to JKN (Secondary worker) participants.

Understanding of Risk

JKN participants understand the risks if they arrear in paying premium fees. Some participants are very confident that JKN would become an aid when exposed to the risk of illness even though in reality respondents and families rarely get sick in the past 4 years.

I understand that everyone has a risk of getting sick, and if it is infection, it costs a lot of money. Therefore, JKN really helps the community when they are sick. (P5)

Understanding of Benefit Packages

The understanding of benefit package is still lacking. The JKN program is actually preventive and promotive programs which is a movement towards healthy community. The preventive program means that healthy people must be managed well, and this is what has been promoted. The benefits received are far greater than the costs they have to pay each month. The existence of JKN which implements a cheap monthly fee system provides an alternative for them to get affordable health services.

JKN is a program to prevent sick people and people in general from going bankrupt when they are sick because of the expensive service costs. (P9)

JKN really helped my family, when my wife had surgery. I didn’t spend a penny, I felt very happy (P12)

For some participants who do not understand the benefits of JKN, they feel that:

JKN program is seen as not as a health insurance, but rather as something that is needed only when they get sick; thus, when they are not sick they will not pay for the premium. (P16)

Theme 2. Financial Ability

Ability to Pay the Contributions

The compliance in paying premiums in low-income communities is generally low. Some respondents should be included in the premium assistance beneficiary, but they are not registered as poor people. Thus, even though if they are included as Secondary worker participants, they cannot afford to pay the premiums even if they are obliged to pay for it.

Based on the socio-economic condition of the community, there are several groups of people who have irregular income. This worsens their condition and one of the answers of why Secondary worker participants are in arrears. For Secondary worker participants who do not have fixed income, paying third Class contributions of IDR. 25.500 (less than US$ 2) per month is considered quite of a challenge.

Our income is not fixed, even to eat is difficult, let alone having to pay a fee of Rp. 25,500 (less than US$ 2)/person/ per month). We can’t afford it. (P20)

Ability to Bear Costs

The reluctance to pay contributions is also related to the number of family members that must be borne by a head of family. Although the contribution value per person is not considered burdensome, the large number of family members caused the total contribution to be paid to be large. This is a significant burden for the head of a family. Routine payment of contributions every month is considered not commensurate compared to paying for incidental health services. The community feels that if a person does not get sick too often, there is no need for a routine payment. In addition, they feel the cost of accessing health services is still affordable.

I have many family members, there are 6 children, I have a wife, the eldest child is married, but not yet working, and as the head of the family, it is difficult for me to pay a very large premium. (P22)

Income Regularity

In general, workers like farmers and small traders have low income and often irregular. It is creating difficulties for the participants to pay premiums. Job loss for workers in the private sector also results in not being able to pay the premium. However, in this situation, the system still charges the premium. Premium debt is resolved by borrowing from other family member. As of now, there is no system of exit strategy.

Theme 3. Self-Attitude

Personal Beliefs

Another factor that influences the reluctance to pay contributions is the values or beliefs adopted by some of JKN participants. This belief is basically encouraging more submission to the Almighty when experiencing pain. They believe that any health-care system will not be able to overcome the Almighty’s destiny. For cases like this, it is better if JKN provides an alternative coverage system that is adjusted to such beliefs or religions. Cooperation with religious leaders or religious teachers to approach these groups is still lacking.

As all diseases are a fate from God, so I just leave it to God. I don’t need to join JKN. (P25)

Family and Society Encouragement

In most cases the decision-making to become JKN participants and willingness to pay premium regularly very much depends on the decision of the head of the family. In addition, the role of the householder is very influential, both in pushing to become JKN participants and paying the premium fees. If the participants forget to pay the premiums on time or because there are other things to be paid, then the householder would pay for their contributions.

I joined JKN because of the encouragement from my parents, who paid my dues as a JKN participant, because I still can’t afford it if I have to pay it myself. (P27)

Social Norms

There is a belief that the JKN program is a type of usury, which is forbidden by religious norms. The understanding of JKN as usury came from the regulation that put a fine in the late payment of premiums. The participants who are overdue for more than 6 months are subject to a 2% fine, which is called usury. At this time, the government has issued Presidential Regulation, and premium payment fines are removed and converted into service fines. Some of them now have changed their opinions about JKN and do not blame consider it as usury.

The existence of a 2% fine in my opinion is usury and is prohibited by religious norms. (R31)

Theme 4. The Operational System

Access

Access to premium payments is perceived to be easy because people can pay directly to BPJSK or through several local banks that collaborate with BPJSK. They can also pay via supermarket franchises. However, for participants who live in remote areas, there are obstacles in premium payments due to additional transportation costs. The access to pay JKN contributions using internet banking links, as in the tax collection, is often constrained by poor internet signals.

I live in remote areas, if you want to pay to the BPJSK office, you have to pay for transportation. (P32)

Penalty

Currently, the penalty for those who fail to pay the premiums for more than 13 months is to pay a 12-month contribution plus an extra of one month premium, and a fine at the hospital of 2.5% of the service fee. The maximum fine in the service is IDR 3.000.000 (USD 210), and the fine may not exceed the maximum limit.

Local Regulation

Local regulations often confuse participants and lead to misunderstandings of the social insurance system. The existence of local regulations can be supportive but can also complicate national policies.

Portability

The JKN card can be used, and participants can be served in health facilities anywhere throughout Indonesia. However, many participants who are out of town and fall ill, often having difficulty in using their JKN card.

I cannot use my JKN card when I am out of town. It makes me so sad. (P34)

Local Government Involvement

The local governments in some villages have been involved in providing dissemination of information about the importance of JKN to the community. Besides that, the village governments are also involved in billing participants who failed to pay the premium because many of them who are billed are from villages. At the beginning of the JKN program, some village government also facilitated participants to pay contributions for the first time.

Village Government and Puskesmas (Community Health Center) should be involved both in conducting information dissemination and communicating about JKN. The Village Government is also involved in the data collection of the participants and those who failed to pay. This is important so that the Village Government can remind their community to pay contributions in a timely manner.

Theme 5. Service Quality

Waiting Time

Service time, especially waiting time, is a common and chronic problem in public health services. Respondents who queue for registration in public hospitals could spend around two hours, similar with the waiting time at its pharmacy. This is due to the large number of patients in the hospital. The long waiting time at the registration, waiting for doctor’s consulting service, as well as in the pharmacy have caused patients to waste a lot of their time to earn income, in addition to worsening the pain.

I was reluctant to go to the hospital, I lost between two - three hours there. Because of the long queue at the registration, waiting for a doctor’s examination, and at the drug section. It makes my whole body ache. (P38)

Discrimination

JKN patients feel distinguished from general patients, especially in terms of the drugs given in the hospital. Pharmacies for general patients and JKN patients are different. In addition, the medicine given is only half a pack, the rest is said to be bought at another pharmacy outside the hospital. The reason stated by the hospital pharmacy staff is because the availability of drugs is limited. Although the price is not expensive, it upsets the JKN participants.

Medicines for JKN patients are not always available at hospital pharmacies, we are often asked to buy them ourselves at other pharmacies. The price of the medicine is not expensive, actually, but having to go back and forth upsets me. (P36)

Theme 6. Intention to Pay for the Contributions

Some JKN participants really do not have the intention to pay. This is due to various reasons such as mistaken beliefs and perceptions of the JKN program, unpleasant experiences in health-care facilities, lack of money, and having other priorities. Consumptive lifestyle is a behavior that causes them to be trapped in the inability to manage finances, including paying contributions on schedule.

Discussion

The substantive theory found in this research is very different from the initial theory used, which was the AMO framework.15 The AMO framework is used as a basic concept of psychology which states that motivation is considered an incentive for behaviour, and ability is an important skill toward behaviour. While opportunity is a contextual and situational constraint that is relevant to a behaviour.17

In this study, we found that someone’s compliance is related to his intention in paying the contributions. This finding is similar to the findings which state that compliance is related to one’s intention in paying contributions.35 In a different context, the intention is also strongly related to the medication compliance among patients.36 The results of this study are also supported by the study which show that attitudes and intentions are positively related in improving compliance of taking medicines.37 According to Mamun et al, intention is a predictor of someone subscribing to health insurance.38 This is in line with the results of this study that intention is a predictor of someone to comply with paying health insurance premiums.

We also show that the intention to pay contributions was related to the five constructs, namely the understanding of INHI, financial ability, self-attitude, operational system, and service quality. This finding is different from the AMO framework. This finding is also different from other researchers, who say that the benefits of health insurance, attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control are the determinants of customer intentions to buy health insurance.38 This finding is also different from the findings of Aprianti who said factors which are related to someone’s intention to consume iron tablets in young women are perceived threats, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and perceived self-efficacy.39

The construct of understanding about the JKN program is related to information dissemination, understanding of risks and understanding the benefit packages. These results are supported by a previous study which reports that someone is interested in buying insurance because they understand the information about the importance of having an insurance.40

The results of this study are also in accordance with the research that concludes that the understanding and knowledge of a low benefit health insurance package in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is led to low participation and willingness to pay.41 This finding is supported by Sheppard’s research which says that people with inadequate health literacy are more likely to show non-adherence.42 Participant compliance can be improved through the provision of information, such as education or dissemination information.43 Compliance of the health insurance scheme is related to the knowledge of health insurance benefit packages.44

Understanding of INHI and self-attitude are 2 aspects of internal factors related to intention to pay. However, there is very little socialization about JKN by the government of Indonesia. The government needs to use a multi-sector approach, such as Ministry of Education and Information-Communication, to carry out real socialization programs so that INHI becomes part of the daily lives of individuals and communities. Financing reform from out of pocket to SHI requires a change in the mindset of individuals, families and communities.

This study also shows that the construct of financial ability is related by the ability to pay contribution, the ability to bear costs and income regularity. The results of this study are supported by Muttaqien, who says that income uncertainty is the cause of informal sector participants not complying with paying premium contributions.45 This result is also in accordance with a previous study which shows that low-income level and lack of financial resources are the main causes for someone not willing to become a CBHI participant.46

For secondary workers, financial ability is full of uncertainty. Existing regulations in Indonesia still assume this segment of participants will have a fixed income. However, in reality, they face the problem of income fluctuations which can be an obstacle in paying contributions. There should be a special mechanism created by the regulator to address this income uncertainty.

The construct of self-attitude is related by personal beliefs, family/society encouragement and social norms. These results are in line with previous studies where patient compliance is due to the support of family, friends and social environment.47,48 This is supported by Buzatu study results, which state that someone is willing to pay the premium contributions and wants to take part in an insurance because of influence from social norms.40

Social norms are informal rules which are followed by all members of the community, but there is no punishment for those who do not obey them. However, family, close friends, and the community would reject them. Life insurance in the United States in 1978 was rejected by the community because it was considered as a desecration which changed the sacred event of death. The results of this study show that there is a group of people who consider that the JKN program is a type of usury because of the penalties.

The construct of the operational system is related to access, penalty, local regulation, portability, and local government involvement. These results are in accordance with the meta-analysis that reveal the factors that prevent someone from becoming a CBHI participant, namely due to access, inadequate policies regarding CBHI, and benefit of the packages that are not what the participant desire.49 The higher income residents have access to become the main beneficiaries of Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) insurance subsidies and Medicaid expansion.50 The results of this study also supported a previous study that shows that government involvement is very important, especially in conducting campaigns and social marketing related to the importance of becoming CBHI participants.51 Community involvement in NHIS activities is key to promoting participant interest and compliance.52

This study shows that the construct of service quality is related to waiting time and discrimination. Long waiting time worsens the pain and causes loss of time to work.53 These results are in line with the research conducted by Adebayo et al, which state that the poor quality of health-care services, including the availability of drugs and medical equipment, poor attitudes of the health-care personnel, and long waiting time have caused people to not participate in CBHI.46 Trust in the CBHI scheme and health-care providers also affect the desire of the community to join the CBHI.46

Compliance of participants is related to the satisfaction relating to health services.54 The compliance of participant is also related to the availability of health services needed by the participants.55 The results of this study are also supported by previous research which states that service quality is the main factor influencing the use of health insurance.56 Poor quality of health services causes a person to stop participating in health insurance.57

The government of Indonesia has tried to improve the quality of health services both in public and private facilities, so that external factors related to compliance can be overcome. However, a stronger emphasis needs to be made on the implementation of quality management in all health facilities.

This study has limitations. First, it does not cover the context outside of Java Island. Thus, it may lose the perceptions based on different ethnicities and customs. The substantive theory constructed should be followed by quantitative research for the needs of inference and generalization. Second, our sample is limited into a few of areas in the West Java Province, as such they may not be representative of the whole province. However, as most of the areas in West Java region share a relatively similar culture, our results may, to some extent, show a picture of the variation of opinions of the people in West Java Province. Future studies covering more areas and sample should provide more accurate results. Lastly, we did not include areas with high compliance to insurance premium payments into our study, as such any comparison to such areas is not possible. Although this is not within the context of our study, it is an important aspect and should be studied in future research.

Conclusion

The non-compliance of JKN participants in paying contributions is affected by factors originating from the internal factors of the participants themselves, namely understanding about JKN, self-attitudes, and financial ability; and from external factors, namely: social influences, quality of healthcare and financing systems. Improvements needed are proper socialization, mechanisms for collecting beneficiary contributions, and strengthening the healthcare system, both for services and the implementation of the financing system.

The independent JKN participants are a very important part in the social health insurance context. Future studies should explore how the sustainability of paying premiums by the independent participants in JKN program reduces the government’s burden in overcoming deficit, and how it will indicate the success of social health insurance in Indonesia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial Kesehatan (BPJSK) at the central and West Java regional office for supporting the study. FZ Kamilah is thanked for her assistance in conducting additional editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial Kesehatan (BPJSK) under the contract no. 230/KTR/0618. BPJSK only had limited role in the conduct of the study and did not interfere with the objectivity of the study.

Disclosure

All authors report no financial interests or conflicts of interest in this study.

References

1. McIntyre D, Thiede M, Dahlgren G, et al. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and of paying for health care in low- and middle-income country contexts? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):858–865. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.001

2. Saksena P, Antunes AF, Xu K, et al. Mutual health insurance in Rwanda: evidence on access to care and financial risk protection. Health Policy. 2011;99(3):203–209. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.009

3. Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, et al. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):111–117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5

4. Faden L, Vialle-Valentin C, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Active pharmaceutical management strategies of health insurance systems to improve cost-effective use of medicines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of current evidence. Health Policy. 2011;100(2–3):134–143. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.020

5. Hartono RK. Equity level of health insurance ownership in Indonesia. National Public Health J. 2007;12(2):93.

6. Jacobs B, Bigdeli M, Pelt M, et al. Bridging community-based health insurance and social protection for health care - A step in the direction of universal coverage? Trop Med Intern Health. 2008;13(2):140–143. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01983.x

7. International Social Security Association. Social security programs throughout the world: Asia and the Pacific; 2014.

8. Ng JYS, Ramadani RV, Hendrawan D, et al. National health insurance databases in Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. Pharmacoecon Open. 2019;3(4):517–526. doi:10.1007/s41669-019-0127-2

9. Dartanto T, Halimatussadiah A, Rezki JF, et al. Why do informal sector workers not pay the premium regularly? Evidence from the national health insurance system in Indonesia. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(1):81–96. doi:10.1007/s40258-019-00518-y

10. Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, et al. Going universal: how 24 developing countries are implementing universal health coverage from the bottom up. In The World Bank.2015.

11. Wilcock RC. The secondary labor force and the measurement of unemployment. In: The Measurement and Behavior of Unemployment. Universities-National Bureau; 1957:167–210.

12. JKN Information Center. JKN principals; 2020. Available from: http://jkn.jamsosindonesia.com/jkn/detail/prinsip#.X7PAx1AxVPY.

13. Agustina R, Dartanto T, Sitompul R, et al. Universal health coverage in Indonesia: concept, progress, and challenges. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):75–102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31647-7

14. Ansyori A 4 years of national health insurance: output, opportunities, and challenges. The National Social Security Council. 2018.

15. Devine J Introducing Sanifoam: a framework to analyze sanitation behaviors to design effective sanitation programs. In Water and Sanitation Program, World Bank. 2019.

16. Kelle U. Theorization from data. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:561–562.

17. Trost J, Skerlajav M, Anzengruber J. The ability–motivation–opportunity framework for team innovation: efficacy beliefs, proactive personalities, supportive supervision and team innovation. Econ Business Rev. 2016;18(1):77–102. doi:10.15458/85451.17

18. Petri H, Govern JM. Motivation Theory, Research and Applications.

19. Simpson EH, Balsam PD. The behavioral neuroscience of motivation: an overview of concepts, measures, and translational applications. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:1–12. doi:10.1007/7854_2015_402

20. Ryan RM, Deci E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

21. McKenzie-Mohr D. Fostering sustainable behavior through community-based social marketing. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):531–537. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.531

22. Taira DA, Wong KS, Frech-Tamas F, et al. Copayment level and compliance with antihypertensive medication: analysis and policy implications for managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(11):678–683.

23. Bleske-Rechek A, Somers E, Micke C, et al. Benefit or burden? Attraction in cross-sex friendship. J Soc Personal Relationships. 2012;29(5):569–596. doi:10.1177/0265407512443611

24. Erickson F. A history of qualitative inquiry in social and educational research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research.

25. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage; 2006:

26. Thornberg R, Charmaz K. Grounded theory and theoretical coding. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:153–167.

27. Lincoln Y, Lynham S, Guba E. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, Revisited. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research.

28. Timulak L. Qualitative meta-analysis. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:484–485.

29. Rapley T. Sampling strategies in qualitative research. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:153–167.

30. Flick U. Triangulation. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research.

31. Charmaz K, Thornberg R, Keane E. Evolving grounded theory and social justice Inquiry. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research.

32. Flick U. Mapping the field. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:153–167.

33. Maxwell JA, Flick U, Chmiel M. Notes toward a theory of qualitative data analysis. In: Flick U, editor. Handbook of Qualit Ative Data Analysis. Sage; 2014:21–31.

34. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage; 2009.

35. Bidin Z, Idris KM, Shamsudin FM. Predicting compliance intention on zakah on employment income in Malaysia: an application of reasoned action theory. J Pengurusan. 2009;28:85–102.

36. Lin CY, Updegraff JA, Pakpour AH. The relationship between the theory of planned behavior and medication adherence in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;61:231–236. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.05.030

37. Fai EK, Anderson C, Ferreros V. Role of attitudes and intentions in predicting adherence to oral diabetes medications. Endocr Connect. 2017;6(2):63–70. doi:10.1530/EC-16-0093

38. Mamun AA, Rahman MK, Munikrishnan UT, et al. Predicting the intention and purchase of health insurance among Malaysian working adults. Sage Open. 2021:1–18. doi:10.1177/21582440211061373

39. Aprianti R, Sari GM, Kusumaningrum T. Factor correlated with the intention of iron tablet consumption among female adolescents. J Ners. 2018;13(1):122–127. doi:10.20473/jn.v13i1.8368

40. Buzatu C. The influence of behavioral factors on insurance decision – a Romanian approach. Procedia Econ Finance. 2013;6(13):31–40. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00110-X

41. Obse A, Hailemariam D, Normand C. Knowledge of and preferences for health insurance among formal sector employees in Addis Ababa: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Res. 2015;15(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0988-8

42. Sheppard-Law S, Zablotska-Manos I, Kermeen M, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to HBV antiviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2018;23(5):425–433. doi:10.3851/IM3219

43. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35–44. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S19801

44. Badacho AS, Tushune K, Ejigu Y, et al. Household satisfaction with a community-based health insurance scheme in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2226-9

45. Muttaqien M, Setiyaningsih H, Aristianti V, et al. Why did informal sector workers stop paying for health insurance in Indonesia? Exploring enrollees’ability and willingness to pay. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252708.

46. Adebayo EF, Uthman OA, Wiysonge CS, et al. A systematic review of factors that affect uptake of community-based health insurance in low-income and middle-income countries. BMC Health Services Res. 2015;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1179-3

47. Goodhand J, Kamperidis N, Sirwan B, et al. Factors associated with thiopurine non-adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(9):1097–1108. doi:10.1111/apt.12476

48. Jack K, McLean SM, Moffett JK, et al. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(3):220–228. doi:10.1016/j.math.2009.12.004

49. Dror DM, Shahed Hossain SA, Majumdar A, et al. What factors affect voluntary uptake of community-based health insurance schemes in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):1–31.

50. Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The affordable care act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:489–505. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044555

51. Donfouet HPP, Makaudze E, Mahieu PA, et al. The determinants of the willingness-to-pay for community-based prepayment scheme in rural Cameroon. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2011;11(3):209–220. doi:10.1007/s10754-011-9097-3

52. Alhassan RKA, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Spieker N, et al. Assessing the impact of community engagement interventions on health worker motivation and experiences with clients in primary health facilities in Ghana: a randomized cluster trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):1–19.

53. Pomerantz A, Cole BH, Watts BV, et al. Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: combining integrated care and advanced access. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):546–551. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.004

54. Onwujekwe O, Onoka C, Uzochukwu B, et al. Is community-based health insurance an equitable strategy for paying for healthcare? Experiences from southeast Nigeria. Health Policy. 2009;92(1):96–102. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.02.007

55. Oriakhi HO, Onemolease EA. Determinants of rural Household’s willingness to participate in community based health insurance scheme in Edo state, Nigeria. Studies Ethno-Med. 2012;6(2):95–102. doi:10.1080/09735070.2012.11886425

56. Kotoh AM, Aryeetey GC, Van der Geest S. Factors that influence enrolment and retention in Ghana’ national health insurance scheme. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(5):443–454. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2017.117

57. De Allegri M, Kouyate B, Becher H, et al. Understanding enrolment in community health insurance in sub-Saharan Africa: a population-based case-control study in rural Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(11):852–858. doi:10.2471/blt.06.031336

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.