Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Exploring residents’ spontaneous collaborative skills in a simulated setting context: an exploratory study on CanMEDS collaborator role

Authors Ouellet K, Sabbagh R, Bergeron L, Mayer S, St-Onge C

Received 2 December 2015

Accepted for publication 9 March 2016

Published 21 July 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 401—405

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S101698

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Kathleen Ouellet,1 Robert Sabbagh,2 Linda Bergeron,3 Sandeep Kumar Mayer,2 Christina St-Onge4

1Center for Health Profession Education, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, 2Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, 3Research Chair in Medical Education, Paul Grand’Maison of the Société des médecins, Université de Sherbrooke, 4Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada

Background: Collaboration is an important competence to be acquired by residents. Although improving residents’ collaboration via interprofessional education has been investigated in many studies, little is known about the residents’ spontaneous collaborative behavior. The purpose of this exploratory study was to describe how residents spontaneously collaborate.

Methods: Seven first-year residents (postgraduate year 1; three from family medicine and one each from ear, nose, and throat, obstetrics/gynecology, general surgery, and orthopedic surgery) participated in two collaborative meetings with actors performing the part of other health professionals (ie, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, nurse, or social worker). Both meetings were built around an issue or conflict with the patients’ families reported by one professional. The residents were required to lead the meeting to collect proper information to reach a joint decision. Two team members analyzed the video recordings of the meetings using an emerging-theme qualitative methodology.

Results: Although the residents spontaneously knew how to successfully communicate with other professionals, they seemed to struggle with the patient-centered approach and the shared decision-making process.

Discussion: Even if the residents performed communication-wise in their collaborative role, they seemed to have perceived themselves as decision makers instead of collaborators in the joint decision process. The results of this study can inform future studies on learning strategies to improve behaviors that would more likely need attention in interprofessional education.

Keywords: interprofessional education, IPE, communication, collaboration

Introduction

The ability to work in an interprofessional team has been recognized as a major competence for practicing medicine. Literature reports positive outcomes in terms of skills, attitudes, and behaviors among professionals working in interprofessional teams, in addition to the positive impacts on the care provided to patients.1 It is therefore, not surprising to see that interprofessional collaboration aptitudes are increasingly being integrated into undergraduate and postgraduate medical-education curricula,2 and figures among educational accreditation standards.3

In Canada, the CanMEDS physician competency framework proposed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada is now being well incorporated into the curricula. This framework includes the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that specialist physicians should develop for better patient outcomes. It is based on seven roles: medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar, and professional. The CanMEDS competency framework defines the key competencies under the “collaborator” role as: “Participate effectively and appropriately in an interprofessional healthcare team” and “Effectively work with other health professionals to prevent, negotiate, and resolve interprofessional conflict”.4 The elements of interprofessional collaboration perceived as being the most important for working effectively in a team include: communication,5 patient- and family-centered approach,6 understanding the roles of other professionals,6 and shared decision making.4

Interprofessional education (IPE), which takes place when learners “from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improved health outcomes”7 is increasingly recognized.8 Most current health care education programs in Canada have integrated IPE into their curriculum, as recommended by the Health Council of Canada.9 Many studies have been conducted on the topic. Some have assessed the influence of IPE activities on the perceptions and attitudes of the participants.10–15 Others have examined IPE from the perspective of improving patient care and have reported on outcomes in this regard.16,17

All these studies are important insofar as they shed light on IPE and make it possible to better initiate students and residents to the practice of interprofessional collaboration. That notwithstanding, very few of the studies have attempted to describe how students, and more specifically residents, spontaneously collaborate. Such knowledge would help to better orient educational strategies. Knowing the learners’ starting point and their initial reactions to a situation of interprofessional collaboration can help identify the best strategies to develop or improve a skill.

The purpose of this exploratory study was to describe how residents – from various postgraduate medical education programs – spontaneously collaborate with other health professionals in a context of simulated short multidisciplinary team meetings in hopes to build on that knowledge for future educational interventions.

Methods

Participants and data collection

After ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee - Education and Social Sciences (Université de Sherbrooke), residents from ten residency programs in a Canadian health science faculty were invited to take part in the study. Seven postgraduate year 1 residents in their first 10 months of training responded to the invitation and agreed to participate (three from family medicine; one each from ear, nose, and throat, obstetrics/gynecology, general surgery; and one from orthopedic surgery) after giving written consent.

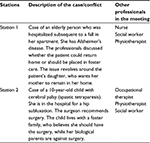

Two collaborative meetings were structured with three standardized actors representing different disciplines. Table 1 presents the cases and the professionals represented. Each meeting was built around an issue or conflict with the patients’ families – reported by one professional – with which the residents had to deal. The instructions given to the resident were to lead the meeting in order to collect proper information and subsequently reach a joint decision. At the end of the meeting, the residents had to communicate what would be said to the patient’s family. Both meetings were 10 minutes long. We chose to limit the time in order to stay close to local reality, although we recognized that lack of time is a recognized barrier to interprofessional collaboration.18 Actors were hired to perform the role of the professionals. Each actor had a script with key sentences to be said at different junctures during the meeting and specific answers to the questions residents could ask. Each meeting was videotaped and each resident participated in both meetings.

| Table 1 Cases presented in the stations and other professionals involved in the meeting |

Data analysis

Two team members (co-coders, KO and LB) analyzed the videos. Open coding was used to identify emergent themes around collaboration. To be consistent with the collaborator role as defined by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the two team members paid particular attention to the aspect of resolving interprofessional conflicts. Since residents were asked to lead the meetings and to reach a joint decision with other professionals, collaborative leadership and shared decision making were also expected to be identified themes. However, the collaborator’s role is large so the two team members conducting the data analysis kept in mind other themes or competencies such as communication, describing the roles and responsibilities of other professionals, collaborative patient–family-centered approach, and team functioning (McMaster-Ottawa Team Observed Structured Clinical Encounter).19 These themes are included in the Team Observed Structured Clinical Encounter checklist, which aims to assess interprofessional team competencies in primary care. To develop this checklist of core competencies, the authors relied on a national set of interprofessional competencies.20 As such, we judged the competencies as important and used them to guide our analysis.

First, the two team members watched all the videos. They met to discuss, construct, and define the emerging themes. Subsequently, coders worked only with verbatim transcripts. Each coder coded half of the verbatim transcripts using NVivo Version 9.0 (QRS International Inc., Burlington, MA, USA). Team members consulted each other’s coding and met to discuss their disagreements until consensus was achieved on how to name and define the themes. The overall impressions of residents’ behavior in the videos were also discussed to bring out further themes. The themes evolved over the coding process and through discussions they became more specific. The two team members iteratively discussed their analysis and presented their findings to the other team members until consensus was achieved about the emerging themes and their descriptions.

Results

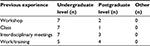

Participants included four males and three females, with ages ranging from 23 to 28 years (mean =24.86, standard deviation =1.95). Their experience with interprofessional collaboration is reported in Table 2. For most participants, this experience was at the level of undergraduate studies. No training was given to them in the context of this study.

| Table 2 Previous experience of the participants (N=7) with interprofessional collaboration |

Two main themes emerged from our results, that is, the skillful communication of the residents that however did not always translate into patient- and family-centered care, and the residents’ difficulty to consider the divergent opinions manifested by the other health professionals.

Skillful communication, but in disregard of patient- and family-centered approach

The participants seemed to have good communication skills as evidenced by their tendency to use open rather than more directive wording. In making proposals, the participants stated these respectfully and openly solicited the opinions of others at the table (station 2):

Before we make a decision, could each one of you tell me what is your assessment [of the patient]. [participant 103]

Another participant, seeking to obtain the assessments of the other professionals around the table, adopted an open – rather than directive – approach (station 2):

Is there anybody who would like to give his assessment? What have you seen? [participant 109]

While there were many examples of successful communication in terms of relational skills, this openness in expression did not always translate into genuine openness to others’ points of view, starting with those of patients and families. The decisions made by most of the residents were inconsistent with a patient- and family-centered approach. For example, in expressing his decision, one participant disregarded the family’s preference for home care for the patient. Instead, he opted to deal with this information subsequently, if that proved necessary (station 1):

If issues with the family arise, [because we haven’t opted for keeping the patient in his home], we can take a second look at it. [participant 108]

It would appear that the solution opted for by most of the participants was not seeking an alternative that would make it possible to take into account the points of view of the patient and family. Instead, the strategy adopted by the participants seems to have been in attempting to persuade the patient and family to opt for the “best” solution, as demonstrated by the verbatim of this participant (station 1):

We should at least try to make the family a little warmer to the idea [of placing the patient]. [participant 109]

Failure to consider divergent points of view of practitioners

Despite the fact that the cases were built around practitioners holding divergent points of view, some participants went so far as to disregard any conflict. In formulating a decision, one participant set aside the contentious aspects discussed, opting instead for a consensual solution that did not fairly represent the points of view of the practitioners (station 2):

I would need to take the biological family aside and explain to them that, in my opinion, and, I believe, according to the specialists around the table, that the ideal option [for the patient], in the best of all possible worlds, would be surgery. [participant 104]

Similarly, another participant opted for inclusive statements using “we” rather than “I”, thereby masking the disagreement expressed by the various practitioners (station 2):

We [need] to explain to them why we think this would be better. [participant 108]

While the instructions referred to joint decision making, the participants appear to have disregarded the “joint” aspect. By disregarding the disagreement expressed by the other practitioners, the participants strayed from the concept of shared decision making.

Discussion

This exploratory study aimed to describe how young junior residents (<10 months of residency) with limited experience in interprofessional collaboration spontaneously behaved in situations involving interprofessional collaboration. The results of our study demonstrate that, when placed in the context of an interprofessional meeting, in a simulated setting context, the residents from various training programs seem to master the “communication” component in this collaboration exercise. Nevertheless, our results suggest that other aspects of collaboration were less spontaneous among these young physicians. Indeed, our participants do not tend to spontaneously place the patients or their families as a central component of their decisions. They did not appear to spontaneously take into consideration the diverging points of view of the patient, family, or other practitioners in arriving at a joint decision.

While communication stands out as an important component in learning interprofessional collaboration,21 recognizing the points of view of others is also essential in teamwork. The residents appear to have considered themselves more as experts, skilled in communication, whose role was to decide rather than to act as collaborators, with all the skills that such a role implies. These results are consistent with the results of Berger et al22 which highlight the importance of providing residents with learning conflict management. Our results indeed show the relevance for residents to learn strategies for managing conflict.

This qualitative exploratory study has limitations. First, the low number of participants does not allow generalization of results since we did not reach a complete saturation of the data. However, this is an exploratory study and the results show the importance of better understanding and fostering the integration of the interprofessional collaboration for residents. There is a potential for representativeness bias in our sample: the participants may have had an interest for the subject of the interprofessional collaboration and it is possible that this influenced their behavior. In addition, the fact that actors were used to play the role of professionals may have an impact on the dynamics of the discussion. Participants may indeed have behaved differently with real experienced professionals. Yet, our results open up future avenues for research aimed at better understanding and fostering the integration of the collaborative role in resident identity. The fact that IPE has been recognized as an essential component in the curricula clearly indicates that the “collaborator” role is not innate in residents and the starting premise is that it can be learned. Not only has IPE’s importance been recognized, but it has been posited that IPE must deal with a variety of issues, including understanding the role of others, communication competencies, and conflict resolution.23 The portrait of the “natural” way of collaborating presented can fuel future research. More specifically, it can contribute to the reflection on the collaborative role as proposed by the CanMEDS physician competency framework, particularly with the addition of milestones in the 2015 version of the framework.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):735–751. | ||

Uden-Holman TM, Curry SJ, Benz L, Aquilino ML. Public health as a catalyst for interprofessional education on a health sciences campus. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(S1):S104–S105. | ||

Comité d’agrément des facultés de médecine du Canada [Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools]. CACMS Standards and Elements; 2015. Available from: https://www.afmc.ca/pdf/CACMS_Standards_and_Elements_June_2014_Effective_July12015.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2015. French. | ||

Frank JR, editor. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework: Better Standards, Better Physicians, Better Care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005:1–40. | ||

San Martín-Rodríguez L, Beaulieu M-D, D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M. The determinants of successful collaboration: a review of theoretical and empirical studies. J Interprof Care. 2005;19 (Suppl 1):132–147. | ||

Horder J. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education; 2014. Available from: http://www.caipe.org.uk/. Accessed 1 June, 2014. | ||

Center for Advancement of Interprofessional education; 2002. Available from: http://caipe.org.uk/about-us/the-definition-and-principles-of-interprofessional-education/. Accessed April 23, 2014. | ||

Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. The effectiveness of interprofessional education: key findings from a new systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(3):230–241. | ||

Bandali K, Niblett B, Yeung TPC, Gamble P. Beyond curriculum: embedding interprofessional collaboration into academic culture. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(1):75–76. | ||

Crutcher RA, Then K, Edwards A, Taylor K, Norton P. Multi-professional education in diabetes. Med Teach. 2004;26(5):435–443. | ||

Kilminster S, Hale C, Lascelles M, et al. Learning for real life: patient-focused interprofessional workshops offer added value. Med Educ. 2004;38(7):717–726. | ||

Pollard K, Miers ME, Gilchrist M. Second year scepticism: pre-qualifying health and social care students’ midpoint self-assessment, attitudes and perceptions concerning interprofessional learning and working. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(3):251–268. | ||

Gould PR, Lee Y, Berkowitz S, Bronstein L. Impact of a collaborative interprofessional learning experience upon medical and social work students in geriatric health care. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):372–373. | ||

Lapkin S, Levett-Jones T, Gilligan C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interprofessional education in health professional programs. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(2):90–102. | ||

Ateah CA, Snow W, Wener P, et al. Stereotyping as a barrier to collaboration: Does interprofessional education make a difference? Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(2):208–213. | ||

Reeves S, Freeth D. The London training ward: an innovative interprofessional learning initiative. J Interprof Care. 2002;16(1):41–52. | ||

King L, Lee JL. Perceptions of collaborative practice between navy nurses and physicians in the ICU setting. Am J Crit Care. 1994;3(5):331–336. | ||

Yeager S. Interdisciplinary collaboration: the heart and soul of health care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2005;17(2):143–148. | ||

McMaster.ca. Hamilton, Ontario: The McMaster-Ottawa Team Observed Structured Clinical Encounter (TOSCE); c. 2010 [updated 2015]. Available from: http://fhs.mcmaster.ca/tosce/. Accessed December 11, 2014. | ||

Curran V, Casimiro L, Banfield V, et al. Research for interprofessional competency-based evaluation (RICE). J Interprof Care. 2009; 23(3):297–300. | ||

Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G. Effective interprofessional teams: “contact is not enough” to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(4):228–234. | ||

Berger E, Chan M-K, Kuper A, et al. The CanMEDS role of collaborator: How is it taught and assessed according to faculty and residents? Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(10):557–560. | ||

Hall P, Weaver L. Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: A long and winding road. Med Educ. 2001;35(9):867–875. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.