Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 16

Experiences of Stigmatization and Discrimination in Accessing Health Care Services Among People Living with HIV (PLHIV) in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

Authors Adekoya P, Lannap FD , Ajonye FA, Amadiegwu S, Okereke I, Elochukwu C, Aruku CA, Oluwaseyi A, Kumolu G , Ejeh M, Olutola AO, Magaji D

Received 7 November 2023

Accepted for publication 1 February 2024

Published 19 February 2024 Volume 2024:16 Pages 45—58

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S447551

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Olubunmi Akindele Ogunrin

Peters Adekoya,1 Faith D Lannap,1 Fatima Anne Ajonye,1 Stanley Amadiegwu,2 Ifeyinwa Okereke,1 Charity Elochukwu,1 Christopher Ayaba Aruku,1 Adeyemi Oluwaseyi,1 Grace Kumolu,1 Michael Ejeh,1 Ayodotun O Olutola,1 Doreen Magaji3

1Centre for Clinical Care and Clinical Research, Abuja, Nigeria; 2Catholic Relief Services, Abuja, Nigeria; 3United States Agency for International Development, Abuja, Nigeria

Correspondence: Faith D Lannap, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: Recent advances in care and treatment have turned HIV into a “chronic but manageable condition”. Despite this, some people living with HIV (PLHIV) continue to suffer from stigma and discrimination in accessing health care services. This study examined the experience of stigma and discrimination and access to health care services among PLHIV in Akwa Ibom State.

Methods: The Center for Clinical Care and Clinical Research (CCCRN), implementing a USAID-funded Integrated Child Health and Social Services Award (ICHSSA 1) project, conducted a community-based cross-sectional survey in 12 randomly selected local government areas in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. A structured quantitative questionnaire was used for data collection. In total, 425 randomly selected PLHIV were interviewed after providing informed consent. Descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were conducted using the data analytical application Stata 14.

Results: The study revealed that 215 PLHIV (50.4%) had been denied access to health care services, including dental care, because of their HIV status in Akwa Ibom State. Respondents reported being afraid of: gossip (78%), being verbally abused (17%), or being physically harassed or assaulted because of their positive status (13%). Self-stigmatization was also evident; respondents reported being ashamed because of their positive HIV status (29%), exhibiting self-guilt (16%), having low self-esteem (38%), and experiencing self-isolation (36%). Women, rural residents, PLHIV with no education, unemployed, single, young people aged between 19 and 29 years, and older adults were more likely to experience HIV-related stigmatization.

Conclusion: Data from the study revealed that the percentage of PLHIV who experience health-related stigmatization because of their HIV status is high in Akwa Ibom State. This finding calls for the prioritization of interventions to reduce stigma, enhance self-esteem, and promote empathy and compassion for PLHIV. It also highlights the need for HIV education for family and community members and health care providers, to enhance the knowledge of HIV and improve acceptance of PLHIV within families, communities, and health care settings.

Keywords: orphans and vulnerable children, household, stigmatization, discrimination, people living with HIV, health-related stigma

Introduction

Globally, about 40 million people were estimated to be living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 2021, and since the beginning of the epidemic, more than 84.2 million people have been infected and about 40.1 million people have died of HIV.1 Nigeria ranks third among the countries with the highest burden of HIV infection in the world, with more than two million people living with HIV (PLHIV) as at 2019 and approximately 45,000 AIDS-related deaths in the country.2,3 The advances in care and treatment have turned HIV into a “chronic but manageable condition”. Regardless, PLHIV continue to suffer from stigmatization and discrimination from their families, communities, and health care providers.4 As a result, HIV/AIDS is increasingly being recognized as not merely a medical problem, but also a social problem.5 Erving Goffman defined stigma as “the phenomenon whereby an individual with an attribute which is deeply discredited by his or her society is rejected as a result of that attribute”, and the results of stigma, which include prejudice, shame, isolation, rejection, and discrimination, are directed at people believed to have that illness or trait.6,7 Stigmatization emanates from a lack of understanding of the illness (ignorance and misinformation), and also because some people have negative attitudes towards or negative beliefs about it.8

HIV-related stigmatization can be described as a process of devaluing people who live with or are connected with the disease.9 Discrimination is one mechanism through which stigma is manifested, and refers to discriminatory behaviors perpetuated by HIV-uninfected individuals towards HIV-infected people.10,11 HIV stigma is primarily due to a fear of HIV, ie fear of contracting the disease, and a lack of knowledge about how HIV transmission occurs.12 Stigmatization manifests in the form of negative attitudes by the public towards those affected, as well as through negative experiences of those living with HIV.13,14 HIV is transmitted predominantly through sexual intercourse. Therefore, in many countries, including Nigeria, HIV is perceived as a consequence of immoral sexual behavior.15 Previous studies have found that women and girls between the ages of 18 to 29 years with HIV/AIDS reported more intense stigma than men, especially women who reside in rural area.16–19

Stangl et al20 devised a comprehensive theoretical framework to interrupt or alleviate the detrimental effects of health-related stigmatization. Within this framework, they delineated the stigmatization process into domains, encompassing drivers and facilitators, stigma markings, and stigma manifestations. These stigmatizations extend beyond affecting the impacted populations to influencing organizations, institutions, and society. The initial domain focuses on factors driving or facilitating health-related stigma, ranging from the fear of infection through casual contact with communicable diseases to social judgment and blame.20,21 Stigma markings, shaped by drivers and facilitators, involve applying a stigma to individuals or groups based on a particular health condition or perceived differences, including demographic and economic characteristics.21 After the application of stigma, it gives rise to various experiences, including discrimination in areas such as housing, forced eviction upon knowledge of health conditions, verbal abuse, and gossip, among other manifestations.

Stigma experiences encompass both internal, known as “self-stigma”, and external stigma. Self-stigma is when a stigmatized group member adopts negative societal beliefs associated with their status. External stigma involves stigmatization from external groups regarding a person’s health condition.22 Perceived stigma involves perceptions of how stigmatized groups are treated in a situation, while anticipated stigma includes expectations of bias if their health condition is disclosed.23,24 Additionally, there is secondary or “associative” stigma, referring to the stigma experienced by family, friends, or health care providers associated with members of stigmatized groups.20,25 HIV-related stigmatization is linked to misinformation about disease transmission, fear, and moral judgments among those living with the virus, and studies indicate that there is discrimination in health care facilities or communities, including denial of care, breaches of confidentiality, and humiliating attitudes, or gossiping.14,26 External stigma from the community leads to internalized stigma, resulting in self-exclusion from social events and anticipating exposure that may lead to adverse health and psychosocial outcomes.14

Evidence from Nigeria27 and other parts of Africa, such as Ghana28 and Ethiopia,15 reveals a level of HIV-related stigmatization and discrimination. Efforts to reduce stigma related to HIV/AIDS will not only help countries to achieve key strategies of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but also protect and promote the human rights of PLHIV.29 This study examined the experience of stigma and discrimination among PLHIV in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria, and their effects on access to health care services.

Methods and Materials

Study Design

The study was a community-based study. It employed a cross-sectional survey procedure, using a multi-stage random and purposive sampling technique with random selection of eligible respondents from 12 local government areas (LGAs) in Akwa Ibom State. The study used primary data and made use of a quantitative method to gather data.

Study Area

The study was conducted in 12 LGAs which were randomly selected from 31 LGAs where the Integrated Child Health and Social Services Award (ICHSSA 1) project has been implemented in Akwa Ibom State, for the data collection exercise. Akwa Ibom State occupies a landmass of 8412 km2 and is bounded to the north by Abia State, to the east by Rivers State, to the west by Cross River State, and to the south by the Atlantic Ocean. It has the longest coastline in Nigeria. Akwa Ibom State consists of 31 LGAs, which are further divided into three senatorial districts, namely, Akwa Ibom North-East, Akwa Ibom North-West, and Akwa Ibom South. The major ethnic groups are Ibibio, Annang, and Oron. The state is one of the largest producers of crude oil in Nigeria and is of major economic importance in the country. ICHSSA 1 is a USAID-funded project designed to mitigate the impact of HIV/AIDS on vulnerable children and their households in Akwa Ibom State. The ICHSSA 1 project includes more than 4000 PLHIV beneficiaries who have been served in the state. The state is located in the South-South region of Nigeria, with a projected population of 5,482,177, according to the 2017 NBS Demographic Population Bulletin. The state has an HIV prevalence of 5.6%, which is the highest among the 36 states of Nigeria, and this state accounts for about 41% of vertically transmitted HIV infections in children in the country.3,30,31 The study population included all the randomly selected beneficiary households in the selected LGAs.

Sample Size Calculation

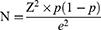

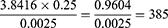

where Z is the value for a selected α level (type 1 error) of 0.05 = 1.96; e is the acceptable margin of error = 5%; p is the estimate of variance = 0.5 (in the absence of any data regarding stigma in PLHIV in Akwa Ibom); therefore, assuming p = 0.5 (maximum variability), q=1−p=1−0.5=0.5.

Therefore, the sample size comes out to be:

However, with the response rate of 90%, the overall sample size used for the study was 425.

Training and Supervision

Adequate numbers of enumerators in Akwa Ibom State, including community case managers and volunteers from among the PLHIV population, were trained by the Center for Clinical Care and Clinical Research, Nigeria (CCCRN), team leader. The training dwelt on study methodology, indicator measurements for the Stigma Index, and quantitative data collection procedures. Consequently, at the end of the training and on the basis of satisfactory performance, qualified interviewers in the team were formed to staff each of the randomly selected LGAs in the state. Two additional teams were kept on reserve/standby. During the interview, teams in each LGA worked closely with the supervisors, while the team leader supervised the exercise. However, adequate arrangement was made for constant communication among the team leader, supervisor, and field members while in the field, especially through WhatsApp, calls, and SMS.

Study Measurement Tool and Data Collection

The study adopted a multi-stage random sampling technique in which four respondents who were HIV positive were randomly selected from all 10 wards in each of the 12 LGAs where the study was implemented. Data were collected by a team comprising the team leader, two supervisors, and 10 trained interviewers who were trained in the content of the research instrument, both in English and in the local language (Ibibio).

The study instrument is a well-structured quantitative questionnaire, which was administered by trained interviewers. All interviews were conducted in a private room, where no one could overhear the discussion. The Stigma Index questionnaire explored the demographics; experiences with stigmatization, discrimination, and advocacy; and experiences with testing, disclosure, and access to services. Other areas were experiences with stigma/discrimination from other people, access to health, educational services, and their experiences with enternal and internal stigmatization.

The outcome variable for this study was defined as health-related stigmatization, which was measured by asking the question “Have you been denied health care services, including dental care services, because of your HIV status in the past 12 months?”. Respondents who responded “Yes” were classified as having experienced health-related stigmatization, while respondents who responded “No” were classified as not having experienced health-related stigmatization because of their HIV status.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were extracted using KoboCollect software, cleaned, and analyzed using Stata software (version 14). Univariate and bivariate analyses were applied. First, we described the characteristics of the study population (frequency counts and percentages of socio-demographic variables, experience of stigmatization and discrimination among PLHIV, and a pie chart showing the percentage distribution of health-related stigma). Secondly, logistic regression was used to test the association between the outcome (health-related stigma) and independent variables (socio-demographic variables, including age, sex, marital status, level of education, employment status, place of residence, and orphan living with you), and finally, a logistic regression analysis was conducted, showing the experience of internal stigmatization on health-related stigma.

Ethical Considerations

The data were collected after obtaining ethical approval from the ethics committee, University of Uyo, Teaching Hospital, Akwa Ibom State. Each study participant was informed in detail about the research objectives, methods, and techniques, and written and signed informed consent was obtained from the participants who were 18 years and above, while for participants under the age of 18 consent was provided by their parent/legal guardian on their behalf. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the data collection procedure was anonymous to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of any information.

Results

A total of 425 PLHIV were included in the analysis. The majority of the respondents were female, and were the head of their households. Also, about one-third of the respondents were between the ages of 30 and 39 years and were rural residents. Most of the respondents were married and about three-quarters of the respondents were employed. In this study, about 41% of the respondents had received secondary education and more than one-quarter of the households had an orphan living with them (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Frequency and Percentage Distribution of the Demographic Characteristics of PLHIV Households in Akwa Ibom State |

Percentage of Health-Related Stigma Among PLHIV in Akwa Ibom State

More than half of the PLHIV in Akwa Ibom State had been denied health care services, including dental care, in the past 12 months because of their HIV status. The overall percentage of health-related stigma among PLHIV was 50.4% (Figure 1).

Experience of External and Internal Stigmatization/Discrimination Among PLHIV

During the past 12 months, 21% of the respondents had felt excluded from social activities and gatherings, 11% had experienced exclusion from religious activities, while more than half of the respondents had experienced exclusion from their family and friends because of their HIV status in the past 12 months. Also, 58% of PLHIV were unable to secure accommodation or had been forced to change their accommodation, while 56% had lost their jobs or source of income because of their HIV status.

About 70% of the respondents were afraid of being gossiped about, 17% were afraid of being verbally abused, and 13% were scared of being physically harassed or assaulted because of their HIV-positive status. As regards self-stigmatization, 29% of the respondents were ashamed of being HIV positive and 16% exhibited self-guilt, while a larger percentage of the respondents (38%) had low self-esteem because of their HIV status. About 5% had thought about taking their own lives (suicidal) because of their HIV status. In the past 12 months, 36% of the respondents had isolated themselves from friends and family, 5% had avoided hospital, 7% had chosen not to attend a social gathering, 5% had decided to stop working/not to apply for jobs or even seek any opportunities, while 12% had decided to stop having sex or a sexual partner because of their HIV status. Also, about 20% of the respondents had decided to stop childbearing for fear of transmitting the disease to their unborn children or sexual partner (Table 2). More than 50% of the respondents had been forced to declare their status in order to attend an educational institution or get a scholarship, and about 43% had been forced to declare their status before they could access health care services. Moreover, in the past 12 months, 54% of the respondents had confronted, challenged, and educated someone who was stigmatizing or discriminating against them, and one-quarter of the respondents had supported someone else with regard to stigma and discrimination. The results also show that about half of the respondents believed that they had experienced stigmatization because they were HIV positive, 12% of the respondents felt that they experienced stigmatization because people were afraid of getting infected with HIV, and 14% had experienced stigmatization because people do not understand what HIV is. Also, about half of the respondents expressed that the root cause of stigmatization is fear of being infected with HIV (Table 3).

|

Table 2 Experience of External Stigmatization and Discrimination Among People Living with HIV |

Experience of Testing, Disclosure, and Treatment Among PLHIV

The results showed that the majority of the respondents had been tested because a family member(s) was ill or had died from HIV, while 28% had been tested because of suspected HIV-related symptoms. About 12% had been tested because of pregnancy and 6% because a family member(s) was HIV positive. With regard to disclosing their status, more than 90% of the respondents had been pressurized into disclosing their status. About 43% of the respondents knew organizations or groups that they can go to for help if they experience stigmatization or discrimination. They also expressed that advocating for the right of all PLHIV (35%) and raising the awareness and knowledge of the public about HIV (31%) should be the important tasks for these organizations to address stigma and discrimination (Table 4).

|

Table 3 Experience of Internal Stigmatization and Discrimination Among People Living with HIV |

|

Table 4 Experience of Testing, Disclosure, and Treatment Among People Living with HIV |

Association of Socio-Demographic Parameters of Study Participants and Health-Related Stigma (Logistic Regression Analysis) (n=425)

Table 5 shows the association of socio-demographic characteristics of the study subjects with health-related stigma using logistic regression analysis. All independent variables were entered in the logistic regression model. The results are presented as odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-values. The results of the study showed that young age, place of residence, marital status, and education were significantly associated with health-related stigma. It was found that respondents who were urban residents were 29% less likely to experience health-related stigmatization compared with rural residents (OR=0.71, 95% CI: 0.279–1.147). With regard to age, significantly, respondents who were between the ages of 19 and 29 years were 18% more likely to experience health-related stigmatization (OR=1.18, 95% CI: 2.119–0.233) compared with respondents aged less than 18 years, while respondents between the ages of 30 and 49 years were less likely to experience health-related stigmatization. The odds of being denied access to health care services because of their HIV status increased significantly, by 36%, among respondents aged 50 years and above (OR=1.36, 95% CI: 2.508–0.204).

|

Table 5 Association of Socio-Demographic Parameters of Study Subjects with Health-Related Stigma (Logistic Regression Analysis) (n=425) |

The results further showed that male respondents were 52% less likely to experience health-related stigmatization compared with female respondents (OR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.527–0.518). With regard to educational status, the odds of being denied access to health care services because of their HIV status increased significantly with no formal education compared with those with higher educational level, as respondents with no formal education were 29% more likely to have experienced health-related stigmatization compared with respondents with education (OR=1.29, 95% CI: 0.443–1.028). Similarly, respondents who were employed were 90% less likely to experience health-related stigma when compared with respondents who were unemployed (OR=0.10, 95% CI: 0.686–0.466). Moreover, the odds of experiencing health-related stigma increased significantly, by 20%, among respondents who were single compared with married respondents (OR=1.20, 95% CI: 0.540–0.957). Finally, respondents with orphaned children living with them were 13% more likely to experience health-related stigma when compared with respondents with no orphaned children residing with them (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 0.194–0.843).

Logistic Regression Analysis Showing the Experience of Internal Stigmatization on Health-Related Stigma (n=425)

Table 6 shows the association between internal stigmatization on health-related stigma using logistic regression analysis. The results revealed that respondents who were afraid of being physically assaulted or harassed because of their status were 11% more likely to experience health-related stigmatization (OR=1.111, 95% CI: 1.836–0.185) when compared with respondents who were afraid of being gossiped about because of their HIV status. Those respondents who were afraid of being verbally insulted were 3% less likely to experience health-related stigmatization (OR=0.977, 95% CI: 1.517–0.438) compared with respondents who were afraid of being gossiped about owing to their HIV status (Table 6).

|

Table 6 Logistic Regression Analysis Showing the Effects of Internal Stigmatization on Health-Related Stigma (n=425) |

Furthermore, the odds of experiencing health-related stigmatization increased significantly among respondents who experienced internal stigmatization, such as blaming self (OR=1.405, 95% CI: 2.178–0.633), and respondents with low self-esteem (OR=1.267 (95% CI: 1.944–0.589) compared with respondents who did not experience any internal stigmatization; similarly, respondents who were ashamed (OR=1.620, 95% CI: 1.319–0.079) and suicidal (OR=1.077, 95% CI: 1.035–1.191) had higher odds of experiencing health-related stigmatization. Also, respondents who thought they were being stigmatized because they looked sick with AIDS (OR=1.527, 95% CI: 2.131–0.923), or thought that people were afraid of being infected by them (OR=1.329, 95% CI: 2.001–0.657), had significantly higher odds of experiencing health-related stigmatization compared with respondents who did not feel stigmatized, and respondents who thought that people were ashamed of associating with them because of their status had higher odds of experiencing health-related stigmatization (OR=1.098, 95% CI: 2.190–0.006).

Discussion

The findings in the study suggest that there is a high level of stigmatization towards PLHIV in accessing health services in Akwa Ibom State. This is consistent with previous studies.4,15,26,32,33 Also in line with previous studies, the level of stigmatization appears to be quite high in this study, with about 50% of PLHIV having been denied access to health care services, including dental care, in the past 12 months, because of their HIV status. This high level of health-related stigmatization may have substantial adverse effects on the day-to-day lives of HIV-infected people. It could result in psychological and emotional stress, inconsistent health care-seeking behavior, and non-disclosure of HIV status.15 Besides, it may also lead to non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy, retention in care, and eventually causing people not to attain viral suppression. By 2030, Nigeria is set to achieve the 95–95–95 goal set by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAID): 95% of all PLHIV will know their HIV status, 95% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 95% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression. Subsequently, high levels of stigmatization and discrimination among PLHIV create the circumstances for spreading HIV and undermine the ability of individuals and communities to protect them, which is one difficulty in achieving the three 95s.

In this study, place of residence, age, educational status, and marital status were significantly associated with health-related stigmatization and discrimination against HIV-infected people. In line with previous studies, respondents who reside in urban areas are less likely to experience health-related stigmatization compared with rural residents.15,26,27 This is because urban residents have access to various mass media, which are a powerful way of sending public health and health promotion messages to the population, and particularly for sending messages relating to stigmatization and discrimination to the community.15

Furthermore, people with no education were more likely to experience health-related stigmatization, which is supported by past studies.26,34,35 Uneducated PLHIV who are not knowledgeable about HIV and modes of transmission of the virus are more likely to experience HIV-related stigma. Young and single individuals were more likely to experience health-related stigma owing to their HIV status, in line with previous studies4,15 which stated that young and single individuals may experience stigmatization; this can be attributed to the fact that most unmarried people are viewed as being promiscuous, and engaging in high-risk behaviors including indiscriminate drug use. Single/unmarried individuals are vulnerable to higher levels of stigmatization because of a lack of social support resulting from isolation, discrimination, prejudice, and lack of psychosocial support from their family members and the society once their status is revealed. The study showed that male individuals were less likely to experience health-related stigmatization compared with female individuals; this is in contrast with previous studies in India,4,36 which reported that males experienced stigmatization more than females, but is consistent with other studies in India.37,38

Individuals who experience self-stigmatization, such as self-guilt or low self-esteem, or individuals who are ashamed of their status or even suicidal, were more likely to experience health-related stigmatization when compared with individuals with no self-stigmatization. This finding is in line with a previous study.26 Individuals who were afraid of being gossiped about or who were afraid of being physically harassed or assaulted because of their HIV status had a higher odds of experiencing health-related stigmatization; this is consistent with a study conducted in Peru, where a respondent declared that “they would rather die than go back to the hospital again for care”, because of being gossiped about by health care professionals.39 The study indicated that respondents who knew organizations or groups who could help during stigmatization were less likely to experience health-related stigmatization. This is consistent with a study conducted in Kenya, which discovered that PLHIV who participated in organization or group activities experienced significantly less stigmatization than individuals who did not. Elimination of discrimination and stigma from the day-to-day life of PLHIV will help in reducing the barriers to counseling and treatment, and improve the quality of care.40

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study had a high completion rate and provided an understanding of stigma characteristics among PLHIV, thereby bringing into focus the areas still in need of further study and improvements in practice. The high response rate was achieved because questionnaire interviews were conducted among the project beneficiaries. However, this study is not without its limitations. One of the limitations was the use of closed-ended (yes/no) questions; a more accurate representation of questions would be the use of a stigma scale. Moreover, the study was conducted in only 12 LGAs, and a greater knowledge of stigma characteristics may have been obtained if the study had been conducted in more LGAs in the state.

Conclusion

In this study, more than half of the PLHIV in Akwa Ibom State experienced health-related stigmatization, as many of the respondents were denied access to healthcare services, including dental care, because of their HIV status. The study indicated that young people, single individuals, uneducated people and rural residents were more likely to experience health-related stigmatization. Also, PLHIV who suffer from internal stigma are more likely to experience HIV health-related stigmatization. This finding serves as a key indicator in generating and implementing policies against health-related stigmatization among PLHIV and other HIV-related stigma in Akwa Ibom State, where HIV is predominant. The older population should be considered when drafting such policies.

Acknowledgment

This paper is made possible by the Center for Clinical Care and Clinical Research Nigeria (CCCRN) with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under cooperative agreement funding for the ICHSSA 1 project. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Funding

This study is funded, as part of the approved scope of work for CCCRN ICHSSA 1 Project on orphan and vulnerable households in Akwa Ibom State, through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), Cooperative Agreement (72062020CA00006).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. UNAIDS. Global HIV statistics; the joint united nations programme on HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland; 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/unaids-data.

2. UNODC, HIVandAID; 2023. Avaialble from: https://www.unodc.org/nigeria/en/hiv-and-aids.html#:~:text=Nigeria%20ranks%20third%20among%20countries,in%20Nigeria%20as%20at%202018.

3. UNAIDSData; 2020. Available from: https://www.avert.org/sites/default/files/styles/responsive_articlecustom_user_desktop_1x/public/Nigeria%20updated%20August2017_2.png?itok=uRThI2xD×tamp=1565964521.

4. Sahoo SS, Khanna P, Verma R, et al. Social stigma and its determinants among people living with HIV/AIDS: a cross-sectional study at ART center in North India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:5646–5651. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_981_20

5. Yi S, Chhoun P, Suong S, Thin K, Brody C, Tout S. AIDS-related stigma and mental disorders among people living with HIV: a cross-sectional study in Cambodia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121461. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121461

6. Arrey AE, Bilsen J, Lacor P, Deschepper R. Perceptions of stigma and discrimination in health care settings towards sub-Saharan African migrant women living with HIV/AIDS in Belgium: a qualitative study. J biosocial sci. 2017;49(5):578–596. doi:10.1017/S0021932016000468

7. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc; 1963.

8. Oke OO, Akinboro AO, Olanrewaju FO, Oke OA, Omololu AS. Assessment of HIV-related stigma and determinants among people living with HIV/AIDS in Abeokuta, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119869109. doi:10.1177/2050312119869109

9. Aggleton P, Wood K, Malcolm A, Parker R. HIV-Related Stigma Discrimination and Human Rights Violations: Case Studies of Successful Programmes. Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2005.

10. Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–1795. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9

11. Mavis Dako-Gyekephyllis Dako-Gyeke, Phd and Emmanuel Asampong Experiences of Stigmatization and Discrimination in Accessing Health Services: voices of Persons Living with HIV in Ghana. Social Work in Health Care, 54:269–285,2015 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0098–1389 print/1541–034X online DOI: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1005268; 2015.

12. Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, Combating AK. HIV stigma in health care settings: what works? J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12(1):15. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-12-15

13. Arinaitwe I, Amutuhaire H, Atwongyeire D, et al. Social Support, Food Insecurity, and HIV Stigma Among Men Living with HIV in Rural Southwestern Uganda: a Cross-Sectional Analysis, HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 657–666; 2021.

14. Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):283–291. doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1451-5

15. Diress GA, Ahmed M, Linger M. Factors associated with discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV among adult population in Ethiopia: analysis on Ethiopian demographic and health survey, SAHARA-J: journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 17: 1,38–44; 2020.

16. Sandelowski M, Lambe C, Barroso J. Stigma in HIV-positive women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(2):122–128. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x

17. Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453

18. Parcesepe AM, Nash D, Tymejczyk O, et al. Gender, HIV-Related Stigma, and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adults Enrolling in HIV Care in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(1):142–150. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02480-1

19. Ekstrand ML, Heylen E, Mazur A, et al. The role of HIV stigma in ART adherence and quality of life among rural women living with HIV in India. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(12):3859–3868. doi:10.1007/s10461-018-2157-7

20. Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(31). doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

21. Hargreaves J, Stangl A, Bond V, et al. P14.14 Intersecting stigmas: a framework for data collection and analysis of stigmas faced by people living with hiv and key populations. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(Suppl2):A203.1–A203. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2015-052270.526

22. Rao D, Desmond M, Andrasik M, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the unity workshop: an internalized stigma reduction intervention for African American women living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(10):614–620. doi:10.1089/apc.2012.0106

23. Zelaya CE, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, Srikrishnan AK, Suniti S, Celentano DD. Measurement of self, experienced, and perceived HIV/AIDS stigma using parallel scales in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24(7):846–855. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.647674

24. Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: the impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(4):634–651. doi:10.1037/a0015815

25. Holzemer WL, Makoae LN, Greeff M, et al. Measuring HIV stigma for PLHAs and nurses over time in five African countries. SAHARA J J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alli. 2009;6(2):76–82. doi:10.1080/17290376.2009.9724933

26. Egbe TO, Nge CA, Ngouekam H, Asonganyi E, Nsagha DS. Stigmatization among People Living with HIV/AIDS at the Kumba Health District, Cameroon. J Int Assoc Pro AIDS Care. 2020;19. doi:10.1177/2325958219899305

27. Dahlui M, Azahar N, Bulgiba A, et al. HIV/AIDS related stigma and discrimination against PLWHA in Nigerian population. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143749

28. Ulasi CI, Preko PO, Baidoo JA, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Kumasi, Ghana. Health Place. 2009;15(1):255–262. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.006

29. Adane B, Yalew M, Damtie Y, Kefale B. Perceived Stigma and Associated Factors Among People Living with HIV Attending ART Clinics in Public Health Facilities of Dessie City, Ethiopia, HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 551–557; 2020.

30. National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA). Global AIDs Response Country Progress Report Nigeria GARPR 2015. National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA). Abuja: Federal Republic of NIGERIA; 2015:1–77.

31. Esther EC. Socio-Cultural Factors Responsible For the High Incidence of HIV in Nigeria: a Study of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. IAA J Art Hum. 2023;10(1):26–31.

32. Oladunni AA, Sina-Odunsi AB, Nuga BB, et al. 3rd. Psychosocial factors of stigma and relationship to healthcare services among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Kano state, Nigeria. Heliyon. Heliyon. 2021;7(4):e06687. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06687

33. Saki M, PhD K, Sima M, Mohammadi E. Perception of patients with HIV/AIDS from stigma and discrimination. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(6):e23638. doi:10.5812/ircmj.23638v2

34. Lipira L, Williams EC, Nevin PE, et al. Religiosity, social support and ethnic identity: exploring “resilience resources” for African American women experiencing HIV-related stigma. J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(2):175–183. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000002006

35. Maughan-Brown B, George G, Beckett S, et al. HIV Risk Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Age-Disparate Partnerships: evidence From KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(2):155–162. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001656.

36. Kumar N, Unnikrishnan B, Thapar R, et al. Stigmatization and discrimination toward people living with HIV/AIDS in a coastal city of South India. J Int Assoc Pro AIDS Care. 2017;16(3):226–232. doi:10.1177/2325957415569309

37. Thomas BE, Rehman F, Suryanarayanan D, et al. How stigmatizing is stigma in the life of people living with HIV: a study on HIV positive individuals from Chennai, South India. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):795–801. doi:10.1080/09540120500099936

38. Doshi SR, Gandhi B. Women in India: the context and impact of HIV/AIDS. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2008;17(3–4):413–442. doi:10.1080/10911350802068300

39. Valencia-Garcia D, Rao D, Strick L, Simoni JM. Women’s experiences with HIV-related stigma from health care providers in Lima, Peru: “I would rather die than go back for care. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38(2):144–158. doi:10.1080/07399332.2016.1217863

40. Turan B, Stringer KL, Onono M, et al. Linkage to HIV care, postpartum depression, and HIV-related stigma in newly diagnosed pregnant women living with HIV in Kenya: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):400. doi:10.1186/s12884-014-0400-4

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.