Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 14

Experiences of Caring for Adolescents Living with HIV (ALHIV): A Qualitative Interview with Caregivers

Authors Kasande M , Natwijuka A , Katushabe E Snr , Otwine Tweheyo A Snr

Received 13 September 2022

Accepted for publication 13 December 2022

Published 21 December 2022 Volume 2022:14 Pages 577—589

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S388715

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Olubunmi Akindele Ogunrin

Meble Kasande, Andrew Natwijuka, Eve Katushabe Snr, Anne Tweheyo Otwine Snr

Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences, Bishop Stuart University, Mbarara, Uganda

Correspondence: Meble Kasande, Bishop Stuart University, Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences, P.O Box 09, Mbarara, Uganda, Tel +256 7812551, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: This study aims at exploring experiences of people caring for adolescents living with HIV, also known as caregivers. By 2021, 150,000 adolescents were living with HIV and 32,000 adolescents were dying of AIDS related causes. HIV/AIDS remains one of the most serious public health problems, especially among the adolescents. This has placed a heavy burden on many caregivers, yet they are essential in caring for ALHIV. However, focus of all interventions has excluded caregivers of ALHIV. Thus, this is the reason why this study is being conducted to find out caregivers’ experience in caring for ALHIV.

Participants and Methods: A phenomenological study was carried out. Purposive sampling was used to select a total of 15 caregivers to participate in the study. These participants were subjected to in-depth semi-structured interviews. Their responses were recorded, transcribed and translated for thematic analysis.

Results: While analyzing the results, six themes emerged. They include: diagnosis and reaction to diagnosis, experiences on adolescent’s HIV serostatus disclosure, stigma and discrimination, care disengagement, and lastly, challenges during care and coping strategies. Caregivers experienced feelings of fear, Guilt, suicidal thoughts after diagnosis. Stigma and discrimination of adolescents living with HIV which was common at school and from the neighbors and the adolescent stage were some of the challenges experienced by the caregivers and it makes it hard to retain ALHIV in care.

Conclusion: Families are the main source of caregiving to the adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV). The study’s findings indicate that caregivers in the families experience challenges related to family needs, and psychological challenges resulting from the adolescence stage. So, families should not be left to shoulder the burden of caring for ALHIV. As a way forward, social network and financial support should also be strengthened for most caregivers as a coping strategy.

Keywords: ALHIV, adolescents living with HIV, caregivers and experiences

Background

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) has negatively impacted and disrupted families. Family members’ productivity and functions have also been negatively affected, especially the caregivers of adolescents living with HIV/AIDS.1 For all the efforts to control increasing numbers of people living with HIV, 38.4 million people globally, were living with HIV at the end of 2021.2 Among these, 36.7 million are adults, 1.75 million are adolescents aged 10–19 years and of these, 1 million adolescents were estimated to be girls while 750,000 were said to be boys. Also by 2021, 1,750,000 adolescents were living with HIV, 150.000 adolescents were newly infected with HIV and 32,000 adolescents were dying of AIDS related causes.3–5

From the above statistics, we can conclude that HIV/AIDS remains one of the most serious public health problems, especially among the adolescents. This is because adolescence is a critical period of development. Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development explains adolescence as a transition from childhood to adulthood where adolescents begin to feel confused and insecure about themselves. They begin to establish a sense of self and they end up experimenting different roles like early marriage and behaviors like drinking alcohol and engage in early sex. Such changed behavior highly exposes them to HIV and also increases its transmission to those who are negative. It also leads to lower percentage of adolescents testing and poor adherence to treatment.

Lower percentage of adolescents testing and adhering poorly to treatment has raised the number of adolescents living with HIV to 82% of the 2.1 million people living with HIV globally. This has had both direct and indirect effects on the population and caregivers of ALHIV have been severely affected. Depending on the intensity of this caregiving, such involvement in caring has been observed to negatively affect their domestic economy, health, physical and psychological wellbeing of caregivers. This has caused feelings of fear, grief, suicidal thoughts, financial burdens and household dysfunctions among these care givers. These dysfunctions are highest in low and middle income countries where they do not have enough income to take care of the family members.6 In these countries, families and in particular parents or guardians are the main source of home-based care for adolescents living with HIV, but are often overwhelmed and burdened by caring for the adolescents living with HIV who are in this critical period at the same time living with HIV7,8 and would want to be supported.

In the past decade, the global community and individual countries have made progress in meeting the needs of children living with HIV. Support is often provided through targeted programs. Unfortunately, this support does not meet the needs of the population and challenges that arise during the adolescence period7 have not been addressed. They have only targeted adults and children living with HIV and their families. It is upon this background that we explored the experiences of caregivers of adolescents living with HIV at Mbarara City Health Centre IV which is found in South Western Uganda.

Methods

Study Design

This was a qualitative study rooted within a phenomenological design. It was employed to explore caregivers’ experiences in regard to caring for adolescents living with HIV. The study was conducted at Mbarara city Health center IV. The qualitative approach was chosen because it was suitable for exploring and describing the unique experiences of caregivers, their challenges and the coping strategies that have been employed by caregivers of adolescents living with HIV.

Study Setting

This study was conducted from the antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinic at Mbarara City Health Centre IV in Mbarara City, South western Uganda. Mbarara City Health Centre is a large volume facility in the center of Mbarara City. They offer specialized services which include the adolescent clinic that is scheduled on a Tuesday every week. The Mbarara City Health Centre facility was chosen because it is one of the facilities with high numbers of adolescents living with HIV. They receive care from the ART clinic. It is located in Mbarara which is the second largest city in Uganda.

Population

The study’s population involved care givers of ALWH (10–19 years) at Mbarara City Health Centre IV, Mbarara City South Western Uganda. Participants were drawn from the Mbarara City Health Centre four adolescent HIV care clinic using the purposive sampling method. This is because the facility runs weekly ART clinic for adolescents. Also 15 care givers who had come with the ALHIV (10–19) to the ART clinic were recruited. Potential participants were easily identified by the researcher since it was an adolescent clinic day. Adolescent peers helped in the identification of these participants.

Inclusion Criteria

All caregivers of who are providing direct care to adolescents living with HIV aged 10 to 19 years and consented to participate in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Caregivers of ALHIV (10–19 years) who were not able to use the English language and Runyankore-Rukiga which were the languages being used in the study.

Sample Size

Fifteen care givers were enrolled and they were determined by saturation of information. Saturation was a point where no more new information was being generated from the in-depth interviews. Data saturation occurs when there is repetition of ideas from participants and information becomes redundant. It is used to determine sample size in qualitative research.

Instrument

A semi-structured interview guide was used to collect the data. This was developed basing on the objectives of the study following the cited literature on this the subject. It comprised of two sections: part on the biographic data (age, sex, relationship with the child etc.) and the main questions which probed the respondents reaction to the diagnosis, their challenges and how they have tried to cope with the challenges.

Data Collection Procedure

The researchers piloted their semi-structured interview guide at Bwizibwera Health Centre Four. This helped them in adjusting and modifying the questions to suit the context and the objectives of the study. After obtaining the Research Ethics Committee approval and administrative clearance from Mbarara City Health Centre four, the researcher then explained to the study participants the study’s topic, its objectives as well as the purpose of the study. They made it clear to the participants that participation was entirely voluntary. A written consent was obtained from all the selected participants of ALHIV (10–19 years).

With the help of the adolescent peers, researchers used purposive sampling to recruit care givers of ALHIV who had come to the adolescent clinic day. Data was collected in July 2022 in a quiet place, precisely in private rooms which were allocated to the researchers within the hospital’s premises. Researchers conducted 15 face to face in-depth interviews with caregivers. Their responses were recorded using an audio recorder and also in a note book. Participants that is both the care givers and the ALHIV adolescent were given two bottles of soda as refreshment during the study. Clients who attended the adolescent clinic and met the inclusion criteria were consented to voluntarily participate in our study. Data was collected using semi-structured interview guides. On average, each in-depth interview took about forty-five minutes.

Data Analysis

We adopted thematic analysis to analyze the data because it allows the researchers to fully reveal the meanings emerging from the data while conceptualizing narrative reports as per significant units. We first wanted to know the full meanings from each transcript by reading them thoroughly and carefully. We therefore noted down the different themes which were identified. The noted themes were compared to each transcript until we got the relevant themes equivalent to our research questions and objectives. We ensured that these themes provide the evidence from the data collected. Through the various discussions about the themes, we finally concluded on them and proceeded with identifying the compelling quotes from the transcripts which tallied with our working themes and research questions. Validity was ensured through continuous reading of the transcripts by all the authors (KM, NA, KE and ATO) Discussion of the codes which made us come to final changes which were incorporated into the findings.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Mbarara University Research Ethics Committee (MUST-REC: 2022–575) since the Research Ethics Committee at Bishop Stuart University was not yet accredited. This study complied in line with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines pertaining research involving human subject participants. We also sought permission from the city health officer and principle medical officer, Mbarara City Health Centre IV and the ART clinic in-charge who allowed us to interact with the caregivers of ALHIV. All the study participants provided consent in writing or through their thumbprint after being informed about the study. Participants were not penalized for refusal to participate in the study. In the informed consent form, Confidentiality was protected throughout data collection to ensure data quality. Participants were informed and authorized publication of the anonymous responses after meaningful analysis.

Results

Demographics of the Participants

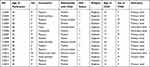

We interviewed a total of 15 caregivers and among them, were 11 females and 4 men in the age category of 30–35 years of age. Most of these caregivers were females and they were HIV seropositive. A considerable number (9) of caregivers were peasants, who dropped out of school at primary level and they were Anglicans by religious denomination as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants |

The thematic analysis examined the challenges caregivers experienced while caring for the ALHIV and 6 major themes and subthemes emerged as illustrated in Table 2 below.

|

Table 2 Themes and Subthemes |

Major Themes

The responses retrieved from caregivers highlighted the challenges they experienced while caring for adolescents living with HIV and the following themes were generated.

Theme 1: Diagnosis and Reaction to HIV Diagnosis

At the time of diagnosis, some caregivers were not aware that their children were already living with HIV. This was found to be common among grandmothers who had no idea of what HIV was. Their reactions to the diagnosis of their children’s status were scaring and it included suicidal thoughts, fear and grief. It was however a different story for the mothers who were HIV positive, it was not that surprising because this was expected by HIV positive mothers who knew there was a possibility of mother to child HIV transmission since some of them did not deliver from hospital. Since adolescents were diagnosed at a younger age and they were biologically related to the care givers; their reactions were divided into two subthemes.

Subtheme 1: Knowledge on Adolescent’s HIV Infection

HIV positive mothers knew their HIV status and there was a possibility of mother to child transmission. So, when the results turned out positive, it was not surprising however, they were not happy as voiced in the quotations below;

She began falling sick severely, later she was diagnosed with HIV, I was not happy since I am already sick and now the child. I started wondering which crime my child had committed. This actually took me a long time to overcome thought the counselors supported and comforted me. I love her more than the rest of the children from the time of diagnosis and they all know why I love her (52-year-old female, HIV +VE CG007)

Another caregiver shared about taking the child to the hospital for an HIV test as early as possible so that she could be enrolled on ART if found positive. Since the couple was on ART, this caregiver knew the importance of early enrollment on ART.

I tested my child when she was around three months but I didn’t see positive results as a new thing because I knew the reason since my wife gave birth from home (30-year-old male, HIV +VE CG008)

Subtheme 2: No Prior Knowledge on Child’s HIV Infection

Caregivers stated that they could not think about HIV because they believed their children were young and thus, they could not have involved themselves in sexual activities which is one of the surest ways of contracting HIV. It was after they got severely sick that they went to the hospital. After HIV tests were carried out, they found out that the children were HIV positive. The caregivers developed feelings of fear and hopelessness. This is because they were wondering how these young people were going to live with HIV for the rest of their lives. A number of questions thus, popped up on how and where they contracted the virus from, yet the caregivers themselves were HIV negative. But these questions could not be answered by either themselves or even the adolescents. Below are their reactions:

I told the health workers to give him medications since I had nothing to do at the time. This is because the mother claimed that the son might have contracted the virus from the house helper and not her. So, I had to let the child begin ART since at the time he was too sick and was about to die of diarrhea and cough (47-year-old female, HIV –VE CG003)

I am not the one who took her to the hospital. It is her aunt who took her there. When she reached there, they discovered that, she was positive. When they returned, the aunt asked me to enter the house. She didn’t want anyone to listen to what we were discussing. She immediately showed me the results. I was numbed by what I saw. I ran short of words. However, I later on asked the girl to tell me how she thinks she got infected. She completely denied and refused to reveal the source of her infection. I was hurt and I never want to recall that story because it brings stress to me which I had put behind me (45-year-old female, HIV –VE CG002)

Theme 2: Experiences on HIV Serostatus Disclosure

Overall, after listening to the caregivers who were interviewed, we concluded that, times of disclosure have been a stressing moment for caregivers. Mostly, grandmothers who have to deal with their own responsibilities and advanced age, are always wondering how their grandchildren will be able to survive those situations. Most caregivers are hopelessness and some of them even contemplate committing suicide. A certain caregiver of a 12-year female adolescent was worried about the future of her daughter. She was worried that her daughter might never get married because of the discrimination and stigma she has witnessed herself. This continuously haunts her.

I keep on wondering about what will happen to her when she grows up because I think she will be neglected by men in case she wants to get married. It has taken me a long time to overcome the above thoughts. However, the counselors have tried to help me out. (45-year-old female, HIV+VE CGO14)

Theme 3: Stigma and Discrimination

There is minimal sensitization and awareness about stigma and discrimination related to HIV among the HIV negative people. It still affects some caregivers and their adolescents living with HIV. However, some caregivers stated that some of their relatives were supportive both financially and emotionally.

Subtheme 1: Surrounding People

Caregivers were found to be so sensitive to the abusive words from the neighbors and the surrounding society to their adolescents living with HIV. Seeing their adolescents being stigmatized and discriminated from others while playing with their neighboring children is something very hard for them to take in. At school, the adolescents reported to their caregivers that whenever they coughed during breakfast, they would be taken to separate rooms claiming that they had tuberculosis and that they were preventing them from spreading it to other children.

Haaaa! Our neighbors abuse her and look at her like an AIDS person and they claim that she is about to die. They also claim she sold herself to acquire AIDS. This annoys me forcing me to exchange words with them. This actually affects her too and she has been stressed for a while though was comforted by the counselor… (45 year old female, HIV –VE CG002)

At first, they used to treat her badly, abusing her using all sorts of words. They assured her that she had AIDS, and that she is about to die. They also kept on telling her that her whole family is going to die. She asks me why they treat her like that. These words have affected her and there was a point when the stigma compelled her to leave school and run away from home. she was found in some place and I was telephoned to picked her up. She once asked me how she got infected with HIV AIDS yet others don’t have it. I explained to her (52-year-old female, +VE CG007)

Subtheme 2: No Discrimination

Some adolescents living with HIV and their caregivers have not experienced any form of discrimination. However, it is because they have not disclosed to anyone their HIV status. Relatives who knew about it treat them with care and love. Neighbors and friends do not know.

Some relatives know about it and they don’t discriminate her, we went at home and disclosed our status to them. So, they don’t treat us in a different way and incase she doesn’t have what to eat they always give us something to eat. (46-year-old female, HIV +VE CG001)

Those who know about it take care of this child well and they have actually helped me in taking care of him well and they mostly give him comforting messages just in case he is lonely (40 Year old male, HIV -VECG009)

Theme 4: Care Disengagement

This theme clarifies the consequences that have resulted from adolescents living with HIV. Adolescence being a period of changed behavior and wanting to discover, the adolescents tend to ask so many questions eg Why they are taking medications etc. They end up disengaging themselves from care which results into losing weight and adhering poorly to ART. This has been discussed under two sub-themes which is weight loss and poor ART adherence and retention in care.

Subtheme 1: Weight Loss

Caregivers were worried about their ALHIV losing and not gaining weight, yet they feed well. This could be because they were not taking ART as they are supposed to. An incidence of throwing away medications was voiced as reported below;

At some point the viral load was high and he had lost weight and I wondered why until when the counselor probed and discovered that he had been throwing away the medications. Counseling was done until he resumed taking his medications and now, he is okay (38-year-old female, +VE CG006)

Subtheme 2: Poor ART Adherence and Retention in Care

Some care givers have disclosed HIV status to the adolescents and given them the ART keep and be in control since caregivers believe that these adolescents are now mature. Adolescence being the age of role confusion and sometimes disrespectful, they intentionally refuse to take medications and their parents find it hard to convince them due to the questions they ask like why I am the only one taking drugs every day? What did I do wrong? As a result they disengage leading to poor ART adherence and retention in care

She refuses to take medication and later falls sick. This disturbs me so much. Otherwise, she wouldn’t have any problem (35-year-old male, HIV –VE CGO12)

Another care giver observed:

She would have no problem but she has refused to take medication and it becomes worse when she is at school, I try to talk to her but still ignores me. She also has also developed a habit of not listening to me at all while taking to her, I don’t know if it is this age or she is angry that I transmitted HIV to her (40-year-old female, HIV +VE CG004)

Theme 5: Challenges with Care Giving

As earlier on asserted in this study, adolescence is a vulnerable stage which is characterized by immature judgment and bad decision making. They ask questions which are very difficult to answer yet, if they are not given answers, they decide not to continue engaging themselves in care.

Caregivers also have financial challenges especially during clinic days. They usually lack transport to the hospital and because of this they have to walk long distances to the hospital. And lastly, they also lack quality food yet they have families to take care of.

Subtheme 1: Challenges with Adolescence

Their age is very difficult to deal with. This has become a burden to the caregivers because they cannot listen to them in case, they want them to avoid a certain vice, for example engaging in early sex which could result into early pregnancies. They also ask their caregivers why they were born different from other children and why they take pills every day. Such questions stress and psychologically challenge the caregivers. Also, some caregivers have not told their adolescents their status because they claim it might be a terrible experience and so they are still preparing for the right time to tell them.

It has not been easy, first of all they are young and cannot advise themselves to make the right decision. So, caregivers also have a burden of simultaneously handling their children’s stupid age and their status at the same time. It becomes so stressful to the caregivers. More so their age is so hard to deal with. For example, the children ask why their parents did not make sure she was born negative like others. Yet some of them are not old enough for one to explain to them. This is a serious burden to the caregivers. (52-year-old female, HIV+VE CG005)

Another care giver also added;

Recently she began acting differently, saying that she was fed up with life and she even wrote on paper showing everyone how she was HIV positive. She could not allow anyone to talk to her. I am sure she didn’t think twice before doing it. I can’t tell you that I know what brought her to that situation. Most probably it might have been that adolescence age. (42-year-old female HIV+VE CG015)

Subtheme 2: Financial Difficulties (Food and Transport)

Most of the interviewed caregivers have no formal education hence they are not employed. They depend on farming which cannot provide enough for their families.

In addition to the burdens of family responsibilities, their adolescents need much supervision to make sure they are adhering well to ART. One care giver said:

She is jobless. Thus, she has nothing to eat. The health workers told me that she has lost weight. I think it’s because she lacks what to eat and because of this, she is stressed due to lack of a job (46-year-old female, HIV+VECG001)

A widowed caregiver lamented that she had lost her husband to AIDS. So, she lacks financial assistance and this financial incapacitation has made her caregiving situation worse.

I give her the necessary care she needs. The only problem is that I am a single parent. This gives me hard time when providing care. The father died last year. That has affected her care. For example, when it’s time to go to the hospital, it is hard for us to get transport to take us up to the hospital. I am the only one to provide for the children. So, she doesn’t receive the right care that she is supposed to get, I even end up missing the real appointment days and come after it has passed which shouldn’t be my wish and this affects my child too (45-year-old female, HIV+VE CG014)

Subtheme 3: No Support from People

The other group of caregivers stated that they had never received any support from anyone and that they would also wish to get support in order to help them reduce on their burden of responsibilities since they also have other siblings to take care of. They also added that they would want support in form of health education because these adolescents are in a critical stage which needs constant reminding about their status so that they can be retained in care. A care giver lamented;

We used to hear that when you have a child like mine, you would be given support from the hospitals. For me I have never got anything like support for my child. I only suffer with her. I have never had a phone call telling me to go and pick for her stuff. I wouldn’t mind any support given to me, be it school fees and what to eat so that she can be healthy so that people fail to realize that she is sick (38-year-old female, +VE CG006)

I have heard that different people get support mostly in education. But I have never received any form of the support (48-year-old female, -VE CG011)

Theme 6: Coping Strategies

Caregivers also shared with us the strategies which they employ in order to cope with the challenges which they experience. They also stressed the importance of supporting caregivers of ALHIV.

Subtheme 1: Support from People

Caregivers revealed that what kept them motivated is the support which they got from relatives and other organizations from the hospital. For example, counseling although this has not been adequate. It is given once in the lifetime of the children.

I only got support during the covid-19 pandemic. I was given 50000 shillings. I used it to buy chicken. This has helped me because my child eats an egg every day. We have also been filling forms to get support in vain (50 year old female, HIV+VE CG010)

Yes, I was given milk and transport the day I brought my child for an HIV test and results turned positive. It helped me so much. I think it also helped me in reducing the stress on the day of diagnosis (42-year-old female, HIV +VE CG015)

Discussion

This study was a qualitative exploration of the experiences, challenges and coping strategies employed by caregivers of adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV). The demographic data showed that there are many females who are primary caregivers compared to men. This is probably because we included only caregivers who were providing direct care to the ALHIV. In the African society care giving is perceived to be a responsibility of females and men can do it only if they are willing. It is believed that men are not supposed to engage themselves in caregiving since it is a role that is traditionally assumed to be for mothers or females in African settings. This has caused female caregivers to experience psychosocial disruption, hopelessness and fear and this could be the reason as to why adolescents were not gaining weight per age. The same findings correlate with the data that was reported in Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana by Uganda Aids Commission and Asuquo et al.9–12,16

Experiences of Care Givers When Caring for the Adolescents Living with HIV

Caregivers described this whole period from the time of diagnosis as a stressful and difficult moment. It is a period that is dominated and stirred by hopelessness, sadness, suicidal thoughts, shame and guilt. At the time of diagnosis, caregivers and their adolescents experienced worrying reactions towards the diagnosis, most especially caregivers who are not biological parents like grandmothers and uncles. The diagnosis usually occurred after adolescents had severely fallen sick. This prompted them to go to the hospital for health checkup. Most of them were found to have no idea about HIV. They thought it was some other kind of sickness not until they got severely sick, resulting into a permanent moment of painful emotions, stress and guilt to the caregivers. This is in line with a study done by Lazarus et al, where study findings also emphasize difficult moments for care takers after the diagnosis turning out to be positive.17 The same experiences are consistent with findings in other studies.14,18,19 In addition to the above experiences, caregivers kept wondering how they would explain this situation to these adolescents. They also got worried about their future and thought it would be difficult for them to get spouses due to their HIV status.

Challenges with the Daily Care of Adolescent Living with HIV (ALHIV)

The different experiences emerged with a variety of challenges which affected both the caregivers and the adolescents as discussed from previous studies.14,17 Adolescence stage which is defined by increased decision making, increased peer pressures and search for self is the most experienced challenge and it is burdensome for caregivers. This is because during this stage, most of the adolescents become disrespectful towards caregivers and fail to listen to important advice and end up with poor adherence to treatment. Disrespect itself to care givers can demotivate them and reduce on the care given to ALWHIV. The findings of a study done by Griffith et al,36 show that if youth are not cared for, it can result into poor adherence and poor retention which means they need to be monitored and cared for to achieve good adherence and retention in care. Such changed behavior and immature decisions make caregivers wonder if it will be possible to keep these adolescents in school so that they can survive this vulnerable stage without messing their future.37,38 They are also worried if they will manage to provide their education.

Some care givers are still challenged on how and when HIV status disclosure to these adolescents should be done, they feel the society should not know therefore consider these adolescents too young to keep that secret. Fear of adolescents asking many questions for example how they acquired the disease contributes to failure of disclosure which keeps them living in fear. These findings are in agreement with the previous findings which reported age as a major factor for failure of disclosure.39,40

HIV stigma and discrimination is also another challenge faced by people living with HIV. This study showed that it was from the neighboring society and schools. Our findings correspond with results from previous studies which showed that stigma still existed among PLHIV and majorly from the society and healthcare settings.20–22 Caregivers also asserted that stigma and discrimination had slightly reduced as a result of counselors’ interventions among those societies. This was because it had affected the adolescent’s health and had caused a high viral load. This is because the adolescents were not adhering to ART. Our findings are comparable to other studies done by Gabriel et al and Katz et al.23,24 According to Ashaba et al, continuous counseling, family and religious support can reduce stigma and discrimination.25

Care givers are challenged by other factors including the adolescence stage which is characterized by immature decisions, early sexual relationships, being argumentative and disrespectful towards caregivers. Such factors have stopped adolescents living with HIV from engaging themselves HIV care.26–29 Disengagement of these adolescents living with HIV from care has resulted into issues related to their health like weight loss, and poor ART adherence.30 This has resulted into continuous weight loss of ALHIV at every hospital visit.

Financial difficulties were also identified as one of the challenges faced by all caregivers.16,32 This makes it difficult to access daily utilities like food, transport to carry them to ART clinics and school fees. Again our findings are similar to previous studies done in Limpopo province and India.33,34 The caregivers lack stable incomes to provide for their needs since most of them are peasants. Studies done by Kang et al, indicate that poverty contributes a lot to the challenges faced by people living with HIV and is associated with poor adherence.34,35

Because of the multiple challenges faced by caregivers, they have adopted coping strategies like support from the hospital through counseling by trained counselors about adherence to antiretroviral therapy and being retained in care. Caregivers have once in their life time received stuff like food and milk to help on the finances spent on food. Rencken et al, study findings highlighted the importance of support to adolescents living with HIV(ALHIV).41 In addition Kose’s study findings showed how support to the adolescents living with HIV with school based support improves adolescents living with HIV wellbeing and health. The findings also show that peer support from family members is also important and it can engage, access and sustain treatment which improves adolescent’s health. Rumana’s study findings showed how caregivers are burdened by depression, anxiety and stress and so they require motivation to keep doing their work effectively more so to informal caregivers.

Conclusion

Care givers experience a variety of challenges and families are the main source of home-based care for the adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV). Therefore, these families experience challenges related to family needs, psychological challenges due to the adolescence stage and so they should not be made the only shoulders to lean on but social network support should be strengthened for most caregivers as a coping strategy. Therefore, the following are the recommendations of the study findings:

First and foremost, Ministry of Health should ensure free access of educational services for ALHIV to relieve them from financial difficulties which they are facing today. The services should include school fees waivers and school feeding schemes. This will reduce their present day unnecessary spending of the little income they have on education and feeding yet they have to take care of their health. Keeping them in school also makes them busy. This prevents them from engaging in premature relationships and bad groups. Ministry of Health and other non-government organizations which are interested in adolescents’ health should also budget for these caregivers. At least let them receive support once in a year most especially those who cannot afford money to buy food.

Furthermore, there is need to address the challenge of adolescence as a vulnerable stage by the care givers and health providers. They should engage ALHIV in activities like preparing their diet and picking their medication on the ART clinic day to keep their minds busy.

Health providers should also provide educational talks. Health education services with fellow ALHIV could reduce stigma and cause more self acceptance. In these education talks, they receive counseling, peer advice and also get people they look up to as their role models.

Strengths and Limitations

We are confident about the findings of the study due to qualitative approach that is significant in exploring participants’ experiences. In addition we managed to reach data saturation. The study was also conducted in the local language familiar to all the study participants and each interview was accorded enough time to capture all the views of the study participants.

The study was limited by the fact that we captured only care givers experiences and not adolescents themselves. Therefore future studies should aim at capturing adolescent’s experiences in regard to their HIV status to eliminate any bias created by this approach.

Abbreviations

HIV, human immuno-deficiency Virus; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ALHIV, adolescents living with HIV; ART, Anti-Retroviral Therapy.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

We obtained ethical approval from the Mbarara University Research Ethics Committee. Informed written consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants upon enrolment. Permission was sought from the town clerk, principle health officer and the ART clinic in charge. All approaches were accomplished in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki to uphold ethical standards and respect for the participants that guaranteed their safety and protected their health and rights.

Consent for Publication

Participants gave their consent for the data to be used for research purposes. They were also assured that any information about them will be anonymized.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank, the town Clerk, Mbarara City health officer and the in-charge of Mbarara city health center IV where this study was carried from, for the support provided and the caregivers who participated in the study.

Author Contributions

All the authors made a significant contribution to this work.ie, from the conception of the research topic, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation. We all took part in drafting, revising and critical reviewing of the article. We also jointly agreed on the version to be published, and the journal in which the article should be submitted for publication. We also agreed to be jointly accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The author(s) did not receive any financial support for this research, its authorship and publication.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Osafo J, Knizek BL, Mugisha J, Kinyanda E. The experiences of caregivers of children living with HIV and AIDS in Uganda: a qualitative study. Global Health. 2017;13(1):72. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0294-9

2. UNAIDS. Fact sheet – world aids day; 2021.

3. UNICEF. Key HIV Epidemiology Indicators for Children and Adolescents Aged 0-19, 2000-2020; 2021.

4. Viviana Simon DDH, Quarraisha Abdool K. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. HHS Public Health. 2010;368(9534):489.

5. Zhang L. ‘I felt I have grown up as an adult’: caregiving experience of children affected by HIV/AIDS in China. j Nursing Scholarships. 2009;35(4):542–550.

6. Atanuriba GA, Apiribu F, Boamah Mensah AB. Caregivers’ Experiences with Caring for a Child Living with HIV/AIDS: a Qualitative Study in Northern Ghana. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794X211003622.

7. Kidman R, Heymann J. Caregiver supportive policies to improve child outcomes in the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic: an analysis of the gap between what is needed and what is available in 25 high prevalence countries. AIDS CARE. 2016;28 Suppl 2(sup2):142–152. doi:10.1080/09540121.2016.1176685

8. Osafo J, Knizek BL, Mugisha J, Kinyanda E. The experiences of caregivers of children living with HIV and AIDS in Uganda: a qualitative study. Global Health. 2017;13(1):548.sa

9. Girum T, Wasie A, Lentiro K, et al. Gender disparity in epidemiological trend of HIV/AIDS infection and treatment in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):51. doi:10.1186/s13690-018-0299-8

10. UAC. Fact Sheets on HIV & AIDS Epidemic in Uganda; 2022.

11. Asuquo EF, Etowa JB, Akpan MI. Assessing Women Caregiving Role to People Living With HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. SAGE J. 2017;7(1):2158244017692013.

12. Asuquo EF, Akpan-Idiok PA. The Exceptional Role of Women as Primary Caregivers for People Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. Soc Sci Humanities. 2020;1:548.

13. Gerstel N, Gallagher SK. Men’s Caregiving: gender and the Contingent Character of Care. Gender and Society. 2001;15:21.

14. Nsibandze BS, Downing C, Poggenpoel M, Myburgh CP. Experiences of grandmothers caring for female adolescents living with HIV in rural Manzini, Eswatini: a caregiver stress model perspective. Afr J AIDS Res. 2020;19(2):123–134. doi:10.2989/16085906.2020.1758735

15. Kiama JM. Association of Literacy-Related Factors to Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence among Sero-Positive Pregnant Women in Murang’a County Referral Hospital, Kenya. Asian J Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;4(2):65.

16. Atanuriba GA, Apiribu F, Boamah Mensah AB. Caregivers’ Experiences with Caring for a Child Living with HIV/AIDS: A Qualitative Study in Northern Ghana. Global Pediatric Health. 2021;8:2333794X211003622.

17. Lazarus R, Struthers H, Violari A. Hopes, fears, knowledge and misunderstandings: responses of HIV-positive mothers to early knowledge of the status of their baby. AIDS Care. 2009;21(3):329–334. doi:10.1080/09540120802183503

18. Evangeli M, Kagee A. A model of caregiver paediatric HIV disclosure decision-making. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(3):338. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1058959

19. Kalomo EN, Lee KF, Lightfoot KH, Freeman R. Resilience among older caregivers in rural Namibia: the role of financial status, social support and health. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61(6):605–622. doi:10.1080/01634372.2018.1467524

20. Fauk NK, Hawke K, Mwanri L, Ward PR. Stigma and Discrimination towards People Living with HIV in the Context of Families, Communities, and Healthcare Settings: a Qualitative Study in Indonesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105424

21. Zhang X, Wang X, Wang H, He X, Wang X. Stigmatization and Social Support of Pregnant Women With HIV or Syphilis in Eastern China: a Mixed-Method Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:764203. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.764203

22. Mathew RS, Phiangjai Boonsuk JA, Dandu M, Sohn AH. Experiences with stigma and discrimination among adolescents and young adults living with HIV in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS CARE. 2020;32(4):530–535. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1679707

23. Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640

24. Camacho G, Kalichman S, Katner H. Anticipated HIV-Related Stigma and HIV Treatment Adherence: the Indirect Effect of Medication Concerns. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(1):185–191. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02644-z

25. Ashaba S, Cooper-Vince CE, Vořechovská D. Community beliefs, HIV stigma, and depression among adolescents living with HIV in rural Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res. 2019;18(3):169–180. doi:10.2989/16085906.2019.1637912

26. Gingaras C, Smith C, Radoi R. Engagement in care among youth living with parenterally-acquired HIV infection in Romania. AIDS Care. 2019;10:1290–1296.

27. Toromo JJ, Apondi E, Nyandiko WM. I have never talked to anyone to free my mind” - challenges surrounding status disclosure to adolescents contribute to their disengagement from HIV care: a qualitative study in western Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1122. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13519-9

28. Enane LA, Apondi E, Aluoch J, et al. Social, economic, and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents retained in or recently disengaged from HIV care in Kenya. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0257210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257210

29. Horter S, Bernays S, Thabede Z. I don’t want them to know”: how stigma creates dilemmas for engagement with Treat-all HIV care for people living with HIV in Eswatini. Afr J AIDS Res. 2019;18(1):27–37. doi:10.2989/16085906.2018.1552163

30. Enane LA, Apondi E, Omollo M. ”I just keep quiet about it and act as if everything is alright” - The cascade from trauma to disengagement among adolescents living with HIV in western Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(4):e25695. doi:10.1002/jia2.25695

31. Crawford TN, Sanderson WT, Thornton A. Impact of poor retention in HIV medical care on time to viral load suppression. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(3):242.

32. Kimera EVS, De MJ. Challenges and support for quality of life of youths living with HIV/ AIDS in schools and larger community in East Africa: a systematic review. BMC. 2019;8:1–9.

33. Nemathaga L, Mafune R, Lebese R. Challenges faced by caregivers of children on antiretroviral therapy at Mutale Municipality selected healthcare facilities, Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Curationis. 2017;40:e1–e9.

34. Kang E, Delzell DAP, McNamara PE, Cuffey J, Cherian A, Matthew S. Poverty indicators and mental health functioning among adults living with HIV in Delhi, India. AIDS Care. 2016;28(4):416–422. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1099604

35. Haacker M, Birungi C. Poverty as a barrier to antiretroviral therapy access for people living with HIV/AIDS in Kenya. Afr J AIDS Res. 2018;17(2):145–152. doi:10.2989/16085906.2018.1475401

36. Griffith DC, Agwu AL. Caring for youth living with HIV across the continuum: turning gaps into opportunities. AIDS Care. 2017;29(10):1205–1211. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1290211

37. Agatha D, Titilola GB, Abideen S, et al. Growth and Pubertal Development Among HIV Infected and Uninfected Adolescent Girls in Lagos, Nigeria: a Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. Glob Pediatr Health. 2022;9:2333794X221082784. doi:10.1177/2333794X221082784

38. Chulani VL, Gordon LP. Adolescent growth and development. Prim Care. 2014;41(3):465–487. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2014.05.002

39. Kodyalamoole NK, Badiger SB, Dodderi SK, Shetty AK. Determinants of HIV status disclosure to children living with HIV in coastal Karnataka, India. AIDS Care. 2021;33(8):1052–1058. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1851018

40. Ngeno B, Waruru A, Inwani I. Disclosure and Clinical Outcomes Among Young Adolescents Living With HIV in Kenya. J Adolesc Health Care. 2019;64(2):242–249. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.013

41. Rencken CA, Harrison AD, Mtukushe B. Those People Motivate and Inspire Me to Take My Treatment”. Peer Support for Adolescents Living With HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2021;20:548.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.