Back to Journals » Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity » Volume 7

Exenatide extended-release: a once weekly treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes

Received 3 January 2014

Accepted for publication 6 May 2014

Published 24 June 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 229—239

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S35331

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Katherine V Mann,1 Philip Raskin2

1PharmD Consulting, LLC, Royal Oak, MD, USA; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA

Background: This article reviews the clinical efficacy, safety, and patient outcomes literature on the first once weekly treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), exenatide extended-release (ER).

Methods: Relevant literature on exenatide ER and T2DM was identified through PubMed database searches from inception until April 2014.

Results: Exenatide ER is the first medication for the treatment of T2DM dosed on a weekly schedule. Exenatide ER is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, the third to be approved in the US, and is associated with a low risk of hypoglycemia, may result in weight loss, and has proven to be a safe and effective treatment for T2DM. Exenatide ER reduces A1c levels by decreasing fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia. The most common adverse events are gastrointestinal in nature, which are lesser in frequency than those observed with short-acting exenatide. Exenatide ER has been shown to be more effective than exenatide twice daily and slightly less efficacious than liraglutide. Exenatide ER is useful as monotherapy and in combination with other oral antidiabetic drugs.

Conclusion: Once weekly treatment options for diabetes such as exenatide ER have the potential to offer substantial convenience for patients who have high medication burden and poor medication adherence.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, long-acting release, GLP-1 receptor agonists

Introduction

The management of diabetes mellitus, in particular type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), has become increasingly complex over the past several decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, treatment options were primarily limited to insulin and sulfonylureas, agents with limitations of hypoglycemia, weight gain, and frequent dosing intervals. Currently there are approximately eleven different classes of antihyperglycemic agents available with which to address this complex chronic metabolic disease.1 These agents are increasingly being used as part of combination therapy strategies as we acknowledge the multifactorial pathophysiology of T2DM.2–4 Recent treatment algorithms and recommendations highlight individualized approaches to patient care and emphasize treatment approaches that minimize risks of hypoglycemia as well as those that are associated with a low risk of weight gain.1,5–7 Incretin-based therapies, which include both the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors meet these criteria.8,9 GLP-1 RAs are known to be more efficacious than DPP-4 inhibitors by virtue of their supraphysiologic delivery of GLP-1 versus inhibition of degradation of native GLP-1 and have greater effects on weight loss, but have less favorable tolerability profiles.10 Of these, exenatide twice daily (BID) was the first GLP-1 RA to be commercially developed.11 Today, an extended-release (ER) formulation of exenatide exists that can be administered once weekly;12 most recently, this agent has become available in a pen delivery device. This review article will summarize the clinical efficacy, safety, and patient outcomes data available for exenatide ER.

The main pathophysiological features of T2DM are decreased insulin sensitivity (insulin resistance), progressive insulin deficiency, and glucagon excess.2 Until recently, little or no emphasis has been placed on the presence of glucagon excess.13 Although much emphasis has been placed on insulin resistance, it is the progressive decrease in insulin secretion that characterizes the disorder. Despite the myriad of treatment options for T2DM that have appeared since the introduction of the thiazolidinediones, most treatments have been inadequate, with almost one half of patients with diabetes having glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels above accepted targets.14 It is clear that what was needed were agents or greater use of combinations of agents that directly target the multiple pathophysiological defects in T2DM.2,4,15,16 Fortunately, what has evolved more recently is our understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease state – the importance of glucagon and the incretin hormones and our ability to influence these parameters.

GLP-1 RAs are relatively recent members of the diabetes treatment arsenal that have gained prominence in European and American treatment recommendations5–7,17 based on attributes including glucose-lowering efficacy with low risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain (with potential for weight loss). These injectable agents are effective in lowering HbA1c levels, but unlike insulin, they work by glucose-dependent mechanisms and are thus associated with a low risk of hypoglycemia, unless used with insulin or other insulin secretagogues.

Like all GLP-1 RAs, exenatide ER has actions that counter all of the pathophysiological defects in T2DM; it directly stimulates insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon, and in many cases results in weight loss, which improves insulin sensitivity.

Pharmacology

Incretins (GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide [GIP]) are gut-derived circulating peptide hormones that potentiate glucose-dependent insulin secretion following ingestion of a meal. Incretin-based therapies for diabetes mellitus were developed in response to the “incretin effect”, wherein oral glucose was observed to stimulate a larger insulin response than intravenous glucose.

The half-life of native GLP-1 is quite short and it is almost immediately inactivated by the enzyme DPP-4. In 2005, the first GLP-1 RA, short-acting exenatide, which is resistant to inactivation by the enzyme DPP-4, was approved for the treatment of T2DM by the US Food and Drug Administration. All GLP-1 RAs lower blood glucose by replicating the activity of GLP-1, which is released in response to a meal; native GLP-1 acts in an endocrine or paracrine fashion to restore euglycemia by multiple mechanisms. These include glucose-dependent stimulation of insulin secretion, suppression of glucagon secretion, slowing of gastric emptying, inhibition of food intake, and modulation of glucose trafficking in peripheral tissues.18 The GLP-1 receptor has wide distribution in mammalian tissues, including pancreatic periductal and beta cells, kidney, heart, stomach, and brain.19 The wide distribution of the GLP-1 receptor explains many of the widespread effects of the GLP-1 RA drugs. However, the distribution of GLP-1 receptors in the body is still not entirely clear given the low specificity and poor sensitivity of the antibodies used at the present time. Drucker questioned whether previous studies are reliable enough to predict anything about the distribution of the GLP-1 receptors because of these technical issues.20 The details of these technical problems are beyond the scope of this manuscript, but Drucker suggests that with additional research, the correct answer will be found.

GLP-1 RAs enhance insulin and reduce glucagon secretion.20 They lower both the fasting and postprandial glucose levels. Moreover, GLP-1 RAs may protect beta cells by enhancing beta cell proliferation and differentiation as well as by inhibiting beta cell death (apoptosis).21 They also stimulate beta cell function by recruiting beta cells to the secretory process and increasing insulin synthesis and secretion. Thus, they might be useful in altering disease progression if given early enough in the disease process when there is still enough beta cell mass and function available to be preserved.22 Whether these effects will be confirmed by clinical trial data remains to be determined. The effects on improving beta cell function have been difficult to demonstrate in humans.

Exenatide (synthetic exendin 4), the parent compound, was shown to be effective at an optimal dose of 0.05–0.2 mg per kg body weight administered BID subcutaneously.21 Exenatide is a GLP-1 RA that binds to the GLP-1 receptor in vitro. This leads to an increase in both the glucose-dependent insulin secretion by the pancreatic beta cell by mechanisms involving cyclic AMP and/or other intracellular signaling pathways.18,21 Thus, exenatide promotes insulin secretion from the pancreatic beta cells in the presence of elevated glucose levels. The drug (exendin-4) in its ER formulation overcomes one of the main barriers to the clinical use of these agents by prolonging its activity so that a single weekly injection is sufficient.

Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics

Exenatide ER is the long-acting formulation that contains the active ingredient of the original exenatide BID formulation. It is supplied as a sterile powder to be suspended in the diluent supplied in a dose of 2 mg per vial. Exenatide ER has been encapsulated in 0.06 mm diameter microspheres of medical grade poly(D,L,-lactide-co-glycolide).22 Following injection of a single dose, exenatide is released from the microspheres over approximately 10 weeks.23 There is an initial period of release of surface-bound exenatide, followed by a gradual release of exenatide from the microspheres that results in two peaks of exenatide in plasma at around week 2 and weeks 6–7, respectively, representing the hydration and erosion of the microspheres.23 After 6 or 7 weeks, the mean plasma exenatide concentration of approximately 300 pg/mL is maintained over weekly dosing intervals, indicating that steady-state plasma concentrations have been achieved. This gradual approach to steady state seems to improve tolerability, as nausea is less frequent with exenatide ER than exenatide BID.24,25 The slow increase in plasma exenatide concentrations reduces the need for gradual dose escalation, as is required for shorter-acting formulations of GLP-1 RAs (eg, exenatide BID).

Efficacy

The clinical trial program for exenatide ER has been wide-ranging. It has been evaluated as monotherapy and as part of almost every common combination strategy, with the exception of use with insulin therapy. The Diabetes Therapy Utilization: Researching Changes in A1c, Weight and Other Factors Through Intervention with Exenatide Once Weekly (DURATION) trials were a series of clinical studies designed to test the superiority of exenatide once weekly as compared to currently available T2DM medications. The duration of these studies ranged from 24–30 weeks. The background therapy, comparators, patient numbers, and baseline and mean changes in A1c are shown in Table 1.24,26–30 Exenatide once weekly was as effective as metformin, as or more effective than pioglitazone, and more effective than sitagliptin, exenatide BID, and even insulin glargine.

| Table 1 Description of the Diabetes Therapy Utilization: Researching Changes in A1c, Weight and Other Factors Through Intervention with Exenatide Once Weekly (DURATION) trials |

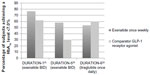

When compared to the other available GLP-1 RAs (currently there are only two: exenatide short-acting, and liraglutide, given once daily), exenatide once weekly falls mid-way in efficacy. Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients in DURATION-1, -5, and -6 in terms of the percentage of patients achieving A1c <7%. Liraglutide once daily was more effective and was associated with less nausea. Exenatide once weekly was more effective in overall A1c reductions than exenatide BID, although exenatide BID has the greatest postprandial effect of all of the GLP-1 RAs (but far less effective in terms of fasting hyperglycemia: −35 mg/dL change in fasting plasma glucose [FPG] versus [vs] −12 mg/dL in FPG for exenatide BID).29

| Figure 1 Percentage of patients achieving A1c <7%, available GLP-1 receptor agonist. |

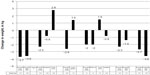

Like all GLP-1 RAs, exenatide ER works in a glucose-dependent fashion, and is thus associated with a low risk of hypoglycemia, unless given with insulin or an insulin secretagogue (eg, a sulfonylurea). Like other GLP-1 RAs, exenatide ER was associated with slow persistent weight loss. Figure 2 shows baseline and mean changes in weight across the DURATION trials.

| Figure 2 DURATION 1–6: weight effects in the DURATION trials (kg). |

After completion of the 30-week randomized portion of DURATION-1, 258 patients continued in the 22-week open-label assessment phase (n=128 once weekly only and 130 who were previously on BID were changed to weekly). Patients continuing with once weekly dosing maintained HbA1c improvements through 52 weeks, and those who were switched from short-acting to ER formulations achieved further HbA1c reductions. At the end of the 52 weeks, both groups achieved a mean HbA1c level of 6.6%, FPG was reduced by <40 mg/dL, and body weight was reduced by <4 kg.32

Taylor et al33 reported on the 2-year follow-up of this cohort. Exenatide ER was well-tolerated during the 2-year study period. Seventy-three percent of the subjects who entered the trial completed 2 years of treatment. After 2 years in this completer population, significant improvements were maintained. HbA1c reductions were −1.71%±0.08%, FPG level change was −40.1 mg/dL, and body weight reductions were 2.61 kg compared with their baseline values. The percentages of subjects who achieved HbA1c levels <7.0% and <6.5% were 60% and 39%, respectively. In addition to decreases in HbA1c levels, there were significant reductions in systolic blood pressure and improvements in lipid profiles. Thus, this study demonstrated sustained glucose control, weight loss, and other nonglycemic effects over the 2-year period.

Davies et al compared the effects of exenatide ER with once or twice daily insulin detemir in type 2 diabetic patients receiving metformin alone or in combination with sulfonylureas. They showed that exenatide ER resulted in a significantly greater proportion of subjects achieving their target HbA1c than with insulin detemir, along with a low risk of hypoglycemia.34

Inagaki et al35 compared the effect of the change in HbA1c level from baseline in a study designed to test the noninferiority of exenatide ER to insulin glargine in Japanese patients with T2DM with inadequate glycemic control on oral antidiabetic drugs. Four hundred and twenty-seven patients were randomized to add either exenatide ER (2.0 mg weekly) or insulin glargine at a starting dose of four units to their current antidiabetes drug treatment. At study end, exenatide ER was statistically noninferior to insulin glargine for the change in HbA1c level from baseline. However, a greater proportion of patients receiving exenatide ER compared with insulin glargine achieved an HbA1c level of <7.0% (42.2% vs 21%) or <6.5% (20.6% vs 4.2%), (P<0.001). Exenatide ER in this study was well-tolerated, with a lower risk of hypoglycemia compared to insulin glargine but with a higher incidence of injection site reactions.

Cui et al compared the safety and efficacy of exenatide ER in Chinese individuals with T2DM. This was the first time that this drug was studied in Chinese individuals. They found that exenatide ER has a pharmacological profile in Chinese individuals that is similar to that observed in other ethnic and racial populations and appears to be safe and generally well-tolerated with the potential to improve glycemic control and decrease body weight without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia.36

In DURATION-2, Bergenstal et al26,37 compared the safety and efficacy of exenatide ER with sitagliptin or pioglitazone in a 26-week trial in individuals with T2DM who were inadequately treated with metformin. Treatment with exenatide ER reduced HbA1c levels and body weight significantly more than sitagliptin or pioglitazone. There was no hypoglycemia, but side effects of exenatide included nausea and diarrhea. Wysham et al reported on a follow-up open-label study of DURATION-2.38 This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of the continued exenatide ER and switching from either sitagliptin or pioglitazone to exenatide ER. Patients who completed a 52-week course of exenatide ER showed a decrease in HbA1c level of 1.6%±0.1% and a weight loss of 1.8±0.5 kg. Patients who switched from sitagliptin to exenatide ER showed a 0.3%±0.1% decline in HbA1c level and a reduction in body weight of 1.1±0.3 kg. Those who switched from pioglitazone to exenatide ER maintained the reduction in HbA1c level that occurred in the double-blind portion of the study but had a weight loss of 3.0±0.3 kg. Thus, patients who switched to exenatide ER from sitagliptin or pioglitazone had improved or sustained glycemic control with weight loss.

Pencek et al39 reviewed the efficacy and tolerability of exenatide ER in patients categorized by their concomitant glucose therapy. This analysis included data from seven randomized controlled trials in patients with T2DM who were treated with exenatide ER for 24–30 weeks. Patients were classified into subgroups according to their baseline glucose-lowering therapy: diet and exercise only, metformin only, metformin plus a sulfonylurea, sulfonylurea plus or minus a thiazolidinedione, or metformin plus a thiazolidinedione. A total of 1,719 patients were included in the analysis. Treatment with exenatide ER was associated with significant improvements from baseline in HbA1c levels, FPG levels, and body weight in all of the groups. There were significant decreases from baseline for both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the metformin and metformin plus sulfonylurea-treated groups and a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure in those treated with diet and exercise. Overall, the most frequent adverse events (AEs) other than hypoglycemia were nausea (14.7%), diarrhea (10.9%), and nasopharyngitis (7.2%). Hypoglycemia was more common when the concomitant therapy included a sulfonylurea. Thus, exenatide ER can be safely combined with other glucose-lowering drugs.

Pinelli and Hurren40 conducted a meta-analysis comparing exenatide ER, exenatide BID, liraglutide, and DPP-4 inhibitors. They reviewed English language papers and abstracts from 2009 and 2010 for studies of at least 24 weeks’ duration. The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c level from baseline and study endpoint. HbA1c reduction and FPG reduction were greatest with the long-acting GLP-1 RAs (liraglutide and exenatide ER). Body weight was similarly reduced between the long-acting GLP-1 agonists and exenatide but favored the long-acting GLP-1 RAs compared with sitagliptin.

Nonglycemic effects

Exenatide ER and other GLP-1 RAs have multiple nonglycemic effects in addition to their effects on glucose metabolism. They slow gastric emptying, increase satiety, and decrease food intake. Chiquette et al,41 reporting on the effects of exenatide ER on cardiovascular risk factors, found that treatment with exenatide ER for 30 weeks reduced apolipoprotein B and the apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1 ratio (P<0.05), independent of glycemic improvement and weight loss. A significant shift in lipoprotein pattern away from small, dense, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was also observed (P<0.05). In addition, exenatide ER increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol even after adjustments for changes in HbA1c level and weight (P<0.05). Triglycerides, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and highly sensitive C-reactive protein were reduced.

Other studies37,41,42 have shown similar changes in lipid and lipoprotein levels as well as reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels and a small increase in heart rate.

One of the most interesting “nonglycemic effects” of the GLP-1 RAs is their effect in the central nervous system. There are GLP-1 receptors in the brain, and injection of GLP-1 directly into the brain causes a reduction in food intake and weight loss in rats.43 In a masked, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in individuals with T2DM who were randomized to receive 3 weeks of treatment with liraglutide or placebo using a 3-step dose escalation scheme of 0.6 mg/day per week to a final dose of 1.8 mg/day, treatment with the GLP-1 agonist was associated with changes in food intake and hunger.44 At the end of each week’s dose escalation, the subjects were served an ad libitum lunch buffet. Assessments included subjective sensations of hunger, fullness, satiety and prospective food consumption, thirst, and nausea using a visual analog scale from before the meal and continuing for the 5-hour postprandial period. The results showed no differences in any of the measures between liraglutide and placebo until the dose reached 1.8 mg/day. At this maximum dose, subjects reported being less hungry, had maximum ratings of fullness, lower ratings for prospective food consumption, and a significantly lower energy intake in connection with the ad libitum lunch buffet (−850 KJ) compared with placebo. There were no differences in satiety or rates of nausea, which were generally low, or feelings of well-being. The results of this study suggest that the mechanism behind the weight loss (and perhaps with the use of GLP-1 RAs) is related to the combined effect of a reduction in appetite and food consumption.

Safety

A major concern to patients and their physicians is that these agents, as well as the DPP-4 inhibitor drugs, may cause pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and thyroid cancer. Tatarkiewicz et al45 studied the long-term effects of exenatide on pancreatic exocrine structure and function in Zucker diabetic rats. The rats were administered BID injections of 0 (control), 6, 40, and 250 μg/kg/day for 3 months. Measurements of body and pancreatic weight, food consumption, HbA1c levels, plasma exenatide levels, and morphometric analyses of pancreatic ductal cell proliferation and apoptosis were performed. Plasma exenatide levels were several-fold higher than therapeutic levels observed in humans. Exenatide treatment improved animal survival, physical condition, glucose concentrations, HbA1c levels, and decreased food intake, and increased serum insulin levels. Exenatide-related minimal-to-moderate islet hypertrophy was observed at doses <6 μg/kg/day with dose-related increases in incidence and degree. Thus, the chronic administration of exenatide in Zucker rats showed no adverse effects on pancreatic structure and function. However, a significant increase in malignant thyroid C-cell carcinomas was observed in female rats receiving exenatide ER at 25 times the clinical exposure compared with controls and higher incidences were noted in males than in controls in all treated groups at <2 times the clinical exposure.46

Butler et al evaluated pathological changes in the pancreatic tissue from humans treated with these incretin-based therapies.47 They reported increased pancreas dysplasia and the potential for glucagon-producing neuroendocrine tumors. However, the conclusions in the Butler paper have recently been severely rejected by Bonner-Weir et al48 in a publication re-analyzing the same histopathological samples as presented by Butler.

Garg et al performed a retrospective evaluation of a large medical and pharmacy database.49 Data for 786,656 patients were analyzed by building Cox proportional hazard models to compare the risk of acute pancreatitis between diabetic and nondiabetic subjects and between exenatide, sitagliptin, and other diabetic medication use. The incidence of acute pancreatitis in the nondiabetic control group, diabetic control group, exenatide group, and sitagliptin group was 1.9, 5.6, 5.7, and 5.6 cases per 1,000 patient-years, respectively. The risk of acute pancreatitis was significantly higher in the combined diabetic groups than in the nondiabetic group (adjusted hazard ratio was 2.1). The risk of acute pancreatitis was similar in the exenatide versus the diabetic control group and sitagliptin versus the diabetic control group. Alves et al40 performed a meta-analysis of 25 studies concerning the risk of GLP-1 RA use and the development of acute pancreatitis, any cancer, and thyroid cancer. Neither exenatide nor liraglutide were associated with acute pancreatitis. The pooled odds ratio for cancer associated with exenatide was 0.86 and 1.35 for liraglutide. Liraglutide was not associated with an increased risk of thyroid cancer, and no malignancies were reported with exenatide use. Romley et al50 conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with T2DM and estimated the association of exenatide use and of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in patients who took the drug for at least 1 year. They found no association between exenatide use and either hospitalization for acute pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

A National Institute of Health (NIH)-sponsored conference was convened to address the issue of pancreatitis risk and pancreatic cancer caused by GLP-1 RA drugs and DPP-4 inhibitors. The conclusion was that at the present time there was no substantial evidence to suggest a relationship between the use of these drugs and either pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.51 The European Medicines Agency came to the same conclusion.52,53

In a combined paper from both the US Food and Drug Agency and the European Medicines Agency, Egan et al53 conducted a careful independent comprehensive review of all preclinical and human data of all incretin-based products (200 clinical trials involving more than 28,000 participants exposed to incretin-based drugs; 15,000 exposed for 24 weeks and 8,500 for 52 weeks or more). Both agencies agreed that “assertions concerning a causal association between incretin-based drugs and pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer are not consistent with the current data”. However, both agencies will continue to monitor before reaching a final conclusion.

Longer-acting GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide ER, are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of certain rare forms of thyroid cancer (ie, medullary thyroid carcinoma [MTC] and multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 [MEN-2]). These contraindications are based on rodent data showing an increased incidence in thyroid C-cell tumors at clinically relevant exposures in rats compared with controls.54 Humans and other primates do not have the same density GLP-1 receptors in their thyroids as do non-primates,55 and the clinical relevance of these findings is unknown at present. Routine screening or monitoring is neither recommended nor required, but because of the uncertainty of these findings and the black box warnings, patients should be counseled about the risk and signs and symptoms of thyroid cancer.

Tolerability

Fineman et al56 evaluated the time course and cross-reactivity of anti-exenatide antibodies and their potential effect on efficacy and safety. Data came from patients in twelve controlled and five uncontrolled exenatide BID and four controlled exenatide once weekly trials. Low-titer anti-exenatide antibodies were common with exenatide treatment (32% exenatide BID, 45% exenatide once weekly patients), but had no apparent effect on efficacy. Higher titer antibodies were less common (5% exenatide BID, 12% exenatide once weekly) and within that titer group, increasing antibody titer was associated with reduced average efficacy that was statistically significant for exenatide once weekly. Other than injection site reactions, anti-exenatide antibodies did not impact the safety of exenatide. Likewise, Faludi et al57 studied exenatide treatment in 58 subjects with T2DM. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) at any time during the study were observed in 40% and 47% of patients with positive and negative treatment-emergent antibodies, respectively. Immune-related AEs were observed in six patients (four were antibody-positive); these authors concluded that antibody formation did not increase the frequency of TEAEs at any time during the study.

The GLP-1 RA family of drugs is generally safe; the most common adverse effect is nausea, which seems to disappear with continued dosing. Nausea can be reduced by altering the dosing schedule (eg, advise patients to start with a lower dose and gradually increase the dose until the therapeutic dose is reached). Consistent with other GLP-1 RAs, nausea and diarrhea are the most common adverse effects of exenatide ER. Table 2 shows the rate of nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting associated with incretin therapies in the DURATION study program. As can be seen, exenatide ER appears better tolerated than exenatide BID and liraglutide once daily, but less so than oral sitagliptin.

| Table 2 Percentage of patients reporting gastrointestinal adverse events with incretin therapies in the DURATION study program |

Ridge et al58 conducted a retrospective analysis comparing the safety and tolerability of exenatide BID and exenatide ER given once weekly. Data were pooled from two open-label comparator-controlled trials directly comparing the two formulations of exenatide. The most common AEs were nausea, diarrhea, injection site pruritus, and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting were less frequent with the once weekly ER formulation than with the BID formulation. These AEs peaked at drug initiation or at dose escalation (exenatide BID) and decreased over time. Few subjects discontinued because of gastrointestinal AEs. Injection site AEs were more common with exenatide ER but also decreased over time. Both formulations were generally safe and well-tolerated.

Norwood et al59 studied the long-term safety profile and changes in glycemic control in patients with T2DM receiving exenatide ER with thiazolidinediones, with or without metformin, over a 2-year period. Seventy-nine percent of subjects completed the 2-year trial. The most common AE was nausea, occurring in 17% of subjects, and 5% of the subjects withdrew from the trial because of this. No major hypoglycemia was reported and minor hypoglycemia was reported in 4% of the subjects.

Patient-focused perspectives

To ascertain what they perceived as the strengths and drawbacks of a weekly injectable medication to improve glycemic control, Polonsky et al60 surveyed a national representative sample of 1,516 adults with T2DM. The results of the survey suggested both pros and cons for using a weekly injectable medication. The pros were greater convenience, better medication adherence, and a less overwhelming sense of treatment. The cons were the consistency of dosage over time, potential forgetfulness, and the cost. Aroda and DeYoung61 reviewed this issue with respect to the similarities and differences between the use of exenatide administered BID or once weekly. In two clinical studies spanning 24 and 30 weeks, significant reductions from baseline were observed in FPG, postprandial glucose, and HbA1c levels. Reductions in body weight and systolic blood pressure and changes in lipids were similar between the two preparations. Gastrointestinal AEs were commonly observed with both preparations but were less frequent with the ER preparation.

Best et al62 assessed treatment satisfaction and weight-related quality of life (QOL) in subjects with T2DM treated with exenatide ER or BID. Two hundred and ninety-five subjects managed with diet/exercise and/or oral glucose-lowering medications received either exenatide ER or BID for 30–52 weeks. After 30 weeks, subjects receiving exenatide BID were switched to exenatide ER until week 52. Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire status (DTSQ-s) and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) were assessed at weeks 30 and 52. Subjects treated with exenatide ER or BID experienced significant and clinically significant improvements in treatment satisfaction and QOL. Subjects who switched from exenatide BID to ER reported further significant improvements.

Finally, Secnik Boye et al63 compared patient-reported outcomes in patients with T2DM treated with either exenatide BID or insulin glargine given once daily.49 At baseline and endpoint, five patient-reported outcome measures, the Vitality Score of the Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36), the Diabetes Symptom Checklist, the EuroQol EQ-5D, the Treatment Flexibility Scale (TFS), and the Diabetes Treatment Questionnaire (DTSQ), were administered. There were significant improvements in all measures with both exenatide and insulin glargine, with no difference between the two.

Cost utility

Beaudet et al64 compared the cost utility of exenatide ER and insulin glargine given once daily using the IMS Core Diabetes Model to project clinical and economic outcomes for patients with T2DM in the UK treated with exenatide ER or insulin glargine. The main outcome measure was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for exenatide ER compared with insulin glargine. They used the price of liraglutide as the estimated cost of the exenatide ER and concluded that at the prices investigated, the cost per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) gained with the use of exenatide ER, when compared with insulin glargine in the UK setting, was within the range normally considered cost-effective by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The improvement in QALY with exenatide ER is mostly related to differences in weight gain between exenatide-treated and insulin glargine-treated patients. However, cost-effectiveness in practice is dependent on the price of exenatide ER.

Guillermin et al65 estimated the clinical benefits and associated clinical benefits of treatment with exenatide ER compared with sitagliptin or pioglitazone in the US. The IMS Core Diabetes Model was used to project lifetime clinical outcomes and complication costs. The cost of glucose-lowering drugs was excluded. Over 35 years, exenatide ER, given once weekly, increased life expectancy and was associated with lower lifetime complication costs compared with sitagliptin or pioglitazone. Cost savings resulted mainly from a lower projected cumulative incidence of cardiovascular diseases and neuropathic complications.

Samyshkin et al66 used the IMS Core Diabetes Model costs to project long-term cost utility based on clinical outcomes and direct medical costs when comparing treating T2DM patients with exenatide ER once weekly or insulin glargine from a US payer prospective. Direct medical costs included pharmacy costs and costs associated with the management of diabetes and its complications. Over a lifetime horizon and compared with insulin glargine, exenatide ER was associated with an incremental cost of US$3,914. Exenatide was projected to increase life expectancy and to improve QALYs, generating an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of US$15,936/QALY. Assuming a payer’s willingness to pay US$50,000/QALY, exenatide once weekly is cost-effective compared to glargine.

Place in therapy

The GLP-1 RAs are now considered a safe and effective therapy for the management of T2DM. Exenatide ER is as safe and perhaps safer and as effective and perhaps more effective as any of the shorter-acting GLP-1 RAs. Historically, the GLP-1 RAs have been used as a “second tier” therapy, often later in the disease and in combination with multiple tablets when glycemic targets have not been achieved – in a sense, as a “last resort” before the initiation of insulin. Recently, the recommendations of the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes,5,6 and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists17 have moved the use of GLP-1 RAs up in the treatment algorithm as an option for initial treatment of T2DM. Although metformin is still considered to be the safest, most efficacious, and certainly the least expensive of the available drugs in the algorithms, the GLP-1 RAs now occupy a place immediately after metformin.

Given that the GLP-1 RAs are injectable and are more expensive by several orders of magnitude, we believe that metformin will continue to be the first drug used. However, we also think that when two drugs are needed, the combination of metformin and a GLP-1 RA is an excellent choice. It probably can also be used when a combination of two oral hypoglycemic agents plus a third drug is required. GLP-1 RAs will probably continue to be used before insulin, given that they are not associated with hypoglycemia and do not usually cause weight loss. Finally, although exenatide ER is not approved for use with basal insulin at present, other GLP1 RAs have been shown to be effective add-on therapy in patients with T2DM who are no longer maintaining glycemic control with an injection of basal insulin alone.67–69

Current research/future of this therapy

There are other long-acting GLP-1s in development. The one closest to patient availability is lixisenatide (Sanofi, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). This drug has the same duration of action as exenatide ER.70 Exenatide in a different formulation has been used in a miniature osmotic pump system that is designed to deliver zero order, continuous subcutaneous release of exenatide at a predetermined rate for up to 12 months with a single placement. Initial human studies have been encouraging.71

Conclusion

GLP-1 RAs are now an accepted treatment option for T2DM. They have multiple positive effects on many of the pathophysiological mechanisms in the disease, result in substantial improvements in HbA1c levels and fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels, often result in weight loss in overweight patients, have many other positive nonglycemic effects, and in our opinion, are safe. Given that exenatide ER is a once weekly injection, this agent may have an advantage over shorter-acting preparations in terms of patient acceptability. The only potential downside to its use is the cost.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013 consensus statement – executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(3):536–557. | |

Defronzo RA. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58(4):773–795. | |

DeFronzo RA, Eldor R, Abdul-Ghani M. Pathophysiologic approach to therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 Suppl 2:S127–S138. | |

Wright EE Jr, Stonehouse AH, Cuddihy RM. In support of an early polypharmacy approach to the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12(11):929–940. | |

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–1379. | |

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1577–1596. | |

Handelsman Y, Mechanick JI, Blonde L, et al; AACE Task Force for Developing Diabetes Comprehensive Care Plan. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract. 2011;17 Suppl 2:1–53. | |

Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies: a clinical need filled by unique metabolic effects. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32 Suppl 2:65S–71S. | |

Drucker DJ. Enhancing the action of incretin hormones: a new whey forward? Endocrinology. 2006;147(7):3171–3172. | |

Aroda VR, Henry RR, Han J, et al. Efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors: meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Ther. 2012;34(6):1247–1258. e22. | |

Iltz JL, Baker DE, Setter SM, Keith Campbell R. Exenatide: an incretin mimetic for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2006;28(5):652–665. | |

Stonehouse A, Walsh B, Cuddihy R. Exenatide once-weekly clinical development: safety and efficacy across a range of background therapies. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(10):1063–1069. | |

Li XC, Zhuo JL. Current insights and new perspectives on the roles of hyperglucagonemia in non-insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15(5):522–530. | |

Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613–1624. | |

DeFronzo RA. Current issues in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Overview of newer agents: where treatment is going. Am J Med. 2010;123(Suppl 3):S38–S48. | |

Zinman B. Initial combination therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: is it ready for prime time? Am J Med. 2011;124(Suppl 1):S19–S34. | |

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(2):327–336. | |

Nielsen LL, Young AA, Parkes DG. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4):a potential therapeutic for improved glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2004;117(2):77–88. | |

Brubaker PL, Drucker DJ. Structure-function of the glucagon receptor family of G protein-coupled receptors: the glucagon, GIP, GLP-1, and GLP-2 receptors. Receptors Channels. 2002;8(3–4):179–188. | |

Drucker DJ. Incretin action in the pancreas: potential promise, possible perils, and pathological pitfalls. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3316–3323. | |

Nielsen LL, Baron AD. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4) for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4(4):401–405. | |

DeYoung MB, MacConell L, Sarin V, Trautmann M, Herbert P. Encapsulation of exenatide in poly-(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres produced an investigational long-acting once-weekly formulation for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(11):1145–1154. | |

Fineman M, Flanagan S, Taylor K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide extended-release after single and multiple dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(1):65–74. | |

Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2008;372(9645):1240–1250. | |

Raskin P, Mohan A. Comparison of once-weekly with twice-daily exenatide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION-1 trial). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(13):2269–2271. | |

Bergenstal RM, Wysham C, Macconell L, et al; DURATION-2 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION-2):a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):431–439. | |

Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3):an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2234–2243. | |

Russell-Jones D, Cuddihy RM, Hanefeld M, et al; DURATION-4 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus metformin, pioglitazone, and sitagliptin used as monotherapy in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-4):a 26-week double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):252–258. | |

Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J, et al. DURATION-5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1301–1310. | |

Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6):a randomised, open-label study. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):117–124. | |

Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al; LEAD-6 Study Group. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009;374(9683):39–47. | |

Buse JB, Drucker DJ, Taylor KL, et al; DURATION-1 Study Group. DURATION-1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(6):1255–1261. | |

Taylor K, Gurney K, Han J, Pencek R, Walsh B, Trautmann M. Exenatide once weekly treatment maintained improvements in glycemic control and weight loss over 2 years. BMC Endocr Disord. 2011;11:9. | |

Davies M, Heller S, Sreenan S, et al. Once-weekly exenatide versus once- or twice-daily insulin detemir: randomized, open-label, clinical trial of efficacy and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin alone or in combination with sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1368–1376. | |

Inagaki N, Atsumi Y, Oura T, Saito H, Imaoka T. Efficacy and safety profile of exenatide once weekly compared with insulin once daily in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral antidiabetes drug(s):results from a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter, noninferiority study. Clin Ther. 2012;34(9):1892–1908. e1891. | |

Cui YM, Guo XH, Zhang DM, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of single- and multiple-dose exenatide once weekly in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2013;5(2):127–135. | |

Bergenstal RM, Li Y, Porter TK, Weaver C, Han J. Exenatide once weekly improved glycaemic control, cardiometabolic risk factors and a composite index of an HbA1c <7%, without weight gain or hypoglycaemia, over 52 weeks. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(3):264–271. | |

Wysham C, Bergenstal R, Malloy J, et al. DURATION-2: efficacy and safety of switching from maximum daily sitagliptin or pioglitazone to once-weekly exenatide. Diabetic Med. 2011;28(6):705–714. | |

Pencek R, Blickensderfer A, Li Y, Brunell SC, Chen S. Exenatide once weekly for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: effectiveness and tolerability in patient subpopulations. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1021–1032. | |

Alves C, Batel Marques F, Macedo AF. A meta-analysis of serious adverse events reported with exenatide and liraglutide: acute pancreatitus and cancer. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2012 Nov;98(2):271–284. | |

Chiquette E, Toth PP, Ramirez G, Cobble M, Chilton R. Treatment with exenatide once weekly or twice daily for 30 weeks is associated with changes in several cardiovascular risk markers. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8:621–629. | |

Robinson LE, Holt TA, Rees K, Randeva HS, O’Hare JP. Effects of exenatide and liraglutide on heart rate, blood pressure and body weight: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1). pii: e001986. | |

Turton MD, O’Shea D, Gunn I, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 1996;379(6560):69–72. | |

Flint A, Kapitza C, Zdravkovic M. The once-daily human GLP-1 analogue liraglutide impacts appetite and energy intake in patients with type 2 diabetes after short-term treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(10):958–962. | |

Tatarkiewicz K, Belanger P, Gu G, Parkes D, Roy D. No evidence of drug-induced pancreatitis in rats treated with exenatide for 13 weeks. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(5):417–426. | |

Extended-release exenatide (Bydureon) for type 2 diabetes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2012;54(1386):21–23. | |

Butler AE, Campbell-Thompson M, Gurlo T, Dawson DW, Atkinson M, Butler PC. Marked expansion of exocrine and endocrine pancreas with incretin therapy in humans with increased exocrine pancreas dysplasia and the potential for glucagon-producing neuroendocrine tumors. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2595–2604. | |

Bonner-Weir S, In’t Veld PA, Weir GC. Reanalysis of study of pancreatic effects of incretin therapy: methodological deficiencies. Diabetes Obes Metab. Epub January 8, 2014. | |

Garg R, Chen W, Pendergrass M. Acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide or sitagliptin: a retrospective observational pharmacy claims analysis. Diabetes Care. Nov 2010;33(11):2349–2354. | |

Romley JA, Goldman DP, Solomon M, McFadden D, Peters AL. Exenatide therapy and the risk of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a privately insured population. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(10):904–911. | |

FDA. [Homepage on the Internet]. Incretin and Pancreatitis. http://www.fda.com/. Accessed 10 June 2014. | |

EMA. [Homepage on the Internet]. Pancreatitis: Incretins. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/. Accessed 10 June 2014. | |

Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs – FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):794–797. | |

Bulchandani D, Nachnani JS, Herndon B, et al. Effect of exendin (exenatide) – GLP 1 receptor agonist on the thyroid and parathyroid gland in a rat model. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;691(1–3):292–296. | |

Bjerre Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, et al. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1473–1486. | |

Fineman MS, Mace KF, Diamant M, et al. Clinical relevance of anti-exenatide antibodies: safety, efficacy and cross-reactivity with long-term treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(6):546–554. | |

Faludi P, Brodows R, Burger J, Ivanyi T, Braun DK. The effect of exenatide re-exposure on safety and efficacy. Peptides. 2009;30(9):1771–1774. | |

Ridge T, Moretto T, Macconell L, et al. Comparison of safety and tolerability with continuous (exenatide once weekly) or intermittent (exenatide twice daily) GLP-1 receptor agonism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(12):1097–1103. | |

Norwood P, Liutkus JF, Haber H, Pintilei E, Boardman MK, Trautmann ME. Safety of exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with a thiazolidinedione alone or in combination with metformin for 2 years. Clin Ther. 2012;34(10):2082–2090. | |

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Bruhn D, Best JH. Patient perspectives on once-weekly medications for diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(2):144–149. | |

Aroda VR, DeYoung MB. Clinical implications of exenatide as a twice-daily or once-weekly therapy for type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2011;123(5):228–238. | |

Best JH, Boye KS, Rubin RR, Cao D, Kim TH, Peyrot M. Improved treatment satisfaction and weight-related quality of life with exenatide once weekly or twice daily. Diabet Med. 2009;26(7):722–728. | |

Secnik Boye K, Matza LS, Oglesby A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in a trial of exenatide and insulin glargine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:80. | |

Beaudet A, Palmer JL, Timlin L, et al. Cost-utility of exenatide once weekly compared with insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):357–366. | |

Guillermin AL, Lloyd A, Best JH, DeYoung MB, Samyshkin Y, Gaebler JA. Long-term cost-consequence analysis of exenatide once weekly vs sitagliptin or pioglitazone for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2012;15(4):654–663. | |

Samyshkin Y, Guillermin AL, Best JH, Brunell SC, Lloyd A. Long-term cost-utility analysis of exenatide once weekly versus insulin glargine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients in the US. J Med Econ. 2012;15 Suppl 2:6–13. | |

Buse JB, Bergenstal RM, Glass LC, et al. Use of twice-daily exenatide in Basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):103–112. | |

Arnolds S, Dellweg S, Clair J, et al. Further improvement in postprandial glucose control with addition of exenatide or sitagliptin to combination therapy with insulin glargine and metformin: a proof-of-concept study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1509–1515. | |

Li CJ, Li J, Zhang QM, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison between liraglutide as add-on therapy to insulin and insulin dose-increase in Chinese subjects with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes and abdominal obesity. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:142. | |

Riddle MC, Forst T, Aronson R, et al. Adding once-daily lixisenatide for type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with newly initiated and continuously titrated basal insulin glargine: a 24-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study (GetGoal-Duo 1). Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2497–2503. | |

Henry RR, Rosenstock J, Logan DK, Alessi TR, Luskey K, Baron MA. Randomized trial of continuous subcutaneous delivery of exenatide by ITCA 650 versus twice-daily exenatide injections in metformin-treated type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2559–2565. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.