Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 15

Evaluation of the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of COVID-19 Prevention Methods Among Hypertensive Patients in North Shoa, Ethiopia

Authors Geleta TA , Deriba BS , Jemal K

Received 2 December 2021

Accepted for publication 4 March 2022

Published 11 March 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 457—471

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S347105

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Haiyan Qu

Tinsae Abeya Geleta,1 Berhanu Senbeta Deriba,1 Kemal Jemal2

1Salale University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health, Fitche, Ethiopia; 2Salale University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Nursing, Fitche, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Tinsae Abeya Geleta, Email [email protected]

Introduction: The occurrence of coronavirus diseases 2019 (COVID-19) has affected more than 247 million populations around the world. People with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, kidney disease, elderly people, and people with weak immunity develop severe types of COVID-19 if exposed to the disease. Therefore, this study aimed to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19 prevention methods among hypertensive patients in North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia.

Methods: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from May 5/2020 to June 5/2020 in public hospitals in the North Shoa zone, Ethiopia. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire and study participants were recruited using a simple random sampling technique. The data were checked for completeness and entered into the EpiData manager version 4.4.1 and transferred to SPSS version 23 for analysis purposes. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression were computed and a significant association was declared with a p-value less than 0.05.

Results: A total of 360 (97.0%) hypertension patients responded. This study revealed that 210 (58.3%) study participants had good knowledge of COVID-19 prevention methods, 199 (55.3%) had a favorable attitude towards COVID-19 prevention methods, and 210 (58.3%) hypertension patients at follow-up practiced COVID-19 prevention methods. Respondents who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly and respondents who followed electronic news media were significantly associated with the use of sanitizer, respondents who had a favorable attitude towards the COVID-19 prevention method were significantly associated with mask-wearing, and respondents who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly were significantly associated with maintaining a physical distance.

Conclusion: Generally, this study finding revealed that the level of knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 prevention among hypertension patients was low. Therefore, increasing knowledge, attitude, and practice on COVID-19 among hypertension patients requires a coordinated effort from the government, non-government, and health professionals.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, hypertension patients, coronavirus

Introduction

COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) is a respiratory disease that is currently emerging transmitted from person to person through small droplets from the mouth or nose.1 Droplets are placed on different surfaces and objects around the person. Other people easily touch the surface, and articles COVID-19 landed then, touching their nose, mouth, and eyes.1 COVID-19 causes flu-like symptoms and, at a severe level, it causes death.2 The period between exposure to COVID-19 and the onset of COVID-19 symptoms is supposed to be 14 days, with the majority of cases occurring five to six days after exposure.3 To reduce the risk of transmission, the community must adhere to approved infection prevention protocols, including regular handwashing with soap, rubbing the hand with an alcohol-based sanitizer, physical distancing, wearing the mask in public, and practicing respiratory hygiene.4 Since May 5, 2020, the WHO has reported more than 3.5 million COVID-19 infections, with a total of 243,401 deaths, in Africa 32, 570 infected cases and 1,1112 deaths, and in Ethiopia 665 cases with 22 deaths were reported by the WHO.5

People with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, kidney disease, elderly people, and people with weak immunity develop severe types of COVID-19 if exposed to the disease.6,7 Chronic disease patients are highly susceptible to COVID-19 due to a declining immune system and poor prognosis from the pandemic.8 This happened because of a low level of immune cells and a high level of cytokines in body fluids. Cytokine release syndrome is an acute systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by multiple organ failure.8

The retrospective study conducted in Zhejiang, China, among patients with COVID-19 disease shows that patients with hypertension develop a severe type of coronavirus when compared with other patients.9 The other study accompanied in Wuhan, China, indicated that the prevalence of the severe type of coronavirus was higher among hypertension patients.10

The study carried out in Ethiopia on chronic disease patients showed that different factors affect the practice of COVID-19 prevention. The study conducted on hypertension and diabetes mellitus disease in the Ambo health facility showed that patients who did not attend formal education; the patient who had poor knowledge about COVID-19; the patient who accesses the source of information less frequently had poor prevention practice.11 The other study conducted in patients with chronic diseases attending Addis Zemen hospital in Ethiopia showed that low educational status, rural residence, and low monthly income were significantly associated with poor knowledge and practice of COVID-19 prevention practice.12

This study was carried out according to the following rationale: different studies showed that hypertension patients are more at risk for COVID-19 than the other patients, according to a study conducted in Ethiopia showed that the prevalence of hypertension was increased alarmingly from time to time in Ethiopia.13,14 Currently, hypertension patients were more at risk of COVID-19 due to frequently visiting the health facility (at-risk area) for a medical check-up and medication collection. Therefore, assessing COVID-19 pandemic knowledge, attitudes, and practice among hypertension patients was essential to reducing COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality. Hence, this study is important to know the knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19 prevention methods among hypertensive patients in North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia. The finding of this study was important to develop a prompt intervention among hypertension patients.

Methods

Study Design, Period, and Setting

An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was accompanied to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19 prevention methods among hypertensive patients in North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia. The study was conducted from May 5, 2020 to June 5, 2020. The study was carried out in the north Showa zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. The zone was established on 10,322.48 km2, with a 1.6 million total population.15 The North Shoa zone has five public hospitals, 65 health centers, and 210 health posts to provide health services to the North Shoa zone community.

Populations

All hypertension patients who had a follow-up in five zonal public hospitals were considered as source population. The study populations were all randomly selected hypertension patients from the five zonal public hospitals. All hypertension patients whose age was older than 18 years and who had follow-up at five zonal hospitals were included in this study. An individual unable to provide valid information due to a medical problem was excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula with the following assumptions by considering 50% (0.5) proportional rate, 5% (0.05) margin of error with 95% CI (confidence interval) after adding 10% nonrespondent rate, the final sample size was 423. Hypertension patients who attended follow-up in five hospitals were less than 10,000; then, the correction formula was used for the sake of sample size adjustment. The final sample size was 371. Five hospitals (specifically Kuyu General Hospital, Fitche General Hospital, Shano Primary Hospital, Gundo Meskel Primary Hospital, and Muke Turi Primary Hospital) were included in this study. The final sample size was proportionally allocated to the five hospitals found in the North Shoa zone based on the number of hypertension patients who attended follow-up for one month. Finally, a simple random sampling technique specifically computer-generated was used to recruit study participants (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Schematic presentation of sample size allocation in hospitals in the North Shoa Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, from May 5, 2020 to June 5, 2020 (n = 360). |

Study Variables

The dependent variables were knowledge, attitude, and practice towards coronavirus. Independent variables were sex, age, marital status, education status, residence, monthly income from the family, occupational status, family size, and source of information.

Data Collection Instrument and Techniques

The structured questionnaire was developed by reviewing different kinds of literature.16,17 The tool was prepared in the English language and translated to the local language (Afan Oromo), and then translated back to the English language by language experts to check its consistency. The questionnaire included different sociodemographic and economic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, and practice questions about COVID-19. The data were collected and supervised by health professionals, specifically five Nurse, and two Public health experts respectively. Before the real data collection process, the supervisor and data collector were trained for two days about the purpose of the study, the data collection methods, and the ethical perspective of the study.

Before actual data collection, the tool was pretested in Sandafa Bake primary hospital in nineteen hypertension patients. Based on the findings of the pretest, the tool was modified for inconsistencies and ambiguity before the actual data collection. Knowledge, attitude, and practice were measured using 12, 10, and 11 questions, respectively. The results were calculated, taking the mean scores as a cut-off point after testing each outcome’s results’ normality distribution. Scores greater than the mean score were considered as good knowledge, a favorable attitude, and good practice, while scores below the mean were considered poor knowledge, unfavorable attitude, and poor practice against coronavirus disease prevention. The tool reliability test was checked by Cronbach’s alpha, which indicated that 0.797 for knowledge, 0.812 for attitude, and 0.784 for practice.

Data Analysis

The data collected were entered into EpiData manager version 4.4.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for data analysis purposes. Sensitivity analysis was performed to reduce the influence of missing data by using multiple imputation methods. The data was then analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Specifically, frequency and percentages were used for descriptive analysis, and bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify factors associated with the COVID-19 prevention practice. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to control for possible confounding effects of the selected variables. The Chi-square test was used to determine the association between knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) scores and categorical variables. The main assumption of the binary logistic regression model was tested. The assumption result showed that there is no existence of a significant effect modification. The multicollinearity among the independent variables was also evaluated using a multiple linear regression model. The evaluation result does not indicate evidence of multicollinearity.

The degree of dependence and an independent variable association was assessed using an odds ratio and statistically significant at 95% of confidence intervals (CI) and p-value (Pv) less than 0.05 was declared. The test’s goodness-fit model was checked by Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness fit. The p-value for the model fitness test was 0.786, 0.867, and 0.796 masks using, maintaining physical distance, and using sanitizer, respectively.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristic

A total of 360 (97% response rate) patients with hypertension participated. The mean age of the respondents was 41.96±14.4 years. Fifty-three percent (191) were men and 188 (52.2%) of the participants had no formal education. The highest proportion of the respondents was married (71.7), orthodox (85.8%), and employed (57.8%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of Hypertension Patients Who Had a Follow-Up in Hospitals of the North Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, from May 5, 2020 to June 5, 2020 (n = 360) |

Sources of COVID-19 Information

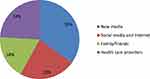

The study indicated that most of the respondents 126 (35%) heard about coronavirus disease in the electronic news media for the first time and the others heard from the healthcare provider 85 (23.6%), social networks 83 (23.1%), and family/friends 66 (18.3%) (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 The COVID-19 source of information among hypertension patients who had a follow-up in hospitals of the North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia, from May 5, 2020 to June 5, 2020 (n = 360). |

Knowledge Towards COVID-19

The knowledge of the study participant mean and standard deviation score was 12.04±2.74. More than half of the respondents knew the sign and symptoms of coronavirus (55.3%). Specifically, the participants knew 299 (83.1%) fever, 291 (80.8%) cough, 174 (43.8%) shortness of breath, and 114 (31.7%) sore throat. The majority of 324 (90.0%) of the participants knew the transmission of the disease from one person to another, and 311 (86.4%) of the respondents knew the virus was transmitted through direct contact. Two hundred and eighty-six (79.4%) of the respondents knew that older people and chronic disease patients were more at risk of developing a severe form of coronavirus. Most of the participants knew coronavirus prevention methods; for example, 309 (88.5%) were hand washed with water and soap, 322 (89.4%) wearing a mask and glove, 312 (86.7%) maintaining physical distance (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Knowledge of COVID-19 Among Hypertension Patients Who Had a Follow-Up in Hospitals of the North Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, from May 5, 2020 to 5 June 5/2020 (n=360) |

Attitude Towards COVID-19

The mean score of the attitude of the study participant with standard deviation was 37.23±8.11 (Figure 3). Half of the participants agree that following the health professional’s recommendation reduces the risk of COVID-19. One hundred and fifty (41.7%) respondents agree that the use of personal protective equipment (mask and glove) prevents the transmission of the virus. Ninety-seven (26.9%) of the participants disagree with coronavirus disease, which results in death in all cases (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Attitude Towards COVID-19 Prevention Among Hypertension Patients Who Had a Follow-Up in Hospitals of the North Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, from May 5, 2020 to 5 June 5/2020 (n=360) |

Practice Towards COVID-19

The mean score of the coronavirus prevention practice of the study participant with a standard deviation was 7.72±2.33 (Figure 3). Two hundred fifty-three (70.3%) of the study participants applied to stay home, and 322 (89.4%) of the study participants maintained physical distance to prevent virus transmissions. The majority of 314 (87.2%), 295 (81.9%), 259 (71.9%) of the respondents wash their hands, wear masks and use sanitizer to prevent coronavirus, respectively (Table 4).

|

Table 4 COVID-19 Prevention Practice Among Hypertension Patients Who Had a Follow-Up in Hospitals of the North Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, from May 5, 2020 to 5 June 5/2020 (n=360) |

Comparison of Sociodemographic Characteristics with Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of COVID-19

Regarding the knowledge of the respondents, 114 (54.3%) and 96 (45.7%) of the male and female participants were knowledgeable, respectively. Most of the age category of ≥45 of the study participants was knowledgeable 95 (45.2%), conversely the age category of 25 to 34 43 (28.6%) was not knowledgeable about COVID-19 followed by the age category of 35 to 44 40 (26.7%). The majority of urban residents 110 (52.4%), employed study participants 121 (57.6%), and study participants with a monthly salary of less than 2000 Ethiopian Birr 140 (66.7%) were knowledgeable about the COVID-19 pandemic. The attitude of the respondent was analyzed. Most of the respondents had an unfavorable attitude toward the prevention of COVID-19. It includes male participants 84 (52.2%), age category ≥45 years 68 (42.2%), urban residents 85 (52.8%), study participants who attend formal education 82 (50.9%), and employed study participants 99 (61.5%). Most of the male participants 118 (56.2%), the age category ≥45 86 (41.0%), urban residents 112 (53.3%), having formal education 114 (54.3%) and employed participants 125 (59.5%) had good practice in COVID-19 prevention and controls. On the other hand, most of the women 77 (51.3%), rural residents 81 (54.0%), without formal education 92 (61.3%), and the unemployed 67 (44.7%) had a poor practice of COVID-19 prevention (Table 5).

Factors Associated with COVID-19 Prevention Practice

To identify factors associated with COVID-19 prevention practice, all sociodemographic and economic variables, categorized knowledge, and attitude were entered into bivariate logistic regression. Then the variable Pv less than 0.25 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression to predict the factors associated with the use of sanitizer or alcohol, using masks, and maintaining physical distance at a Pv of < 0.05. Respondents who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly were 2.5 times more likely to use sanitizer than their counterparts [AOR=2.5; 95% CI= (1.12–5.66)]. Respondents who get information from the electronic news media were 2.95 times more likely to use sanitizer when compared with respondents who get information from the health care providers [AOR = 2.95; 95% CI = (1.47–5.91)]. Respondents who had a favorable attitude towards COVID-19 prevention practice were 2.4 times more likely to wear masks than those with an unfavorable attitude [AOR = 2.4; 95% CI = (1.38–4.11)]. Participants who received less than two thousand Ethiopian Birrs per month were 4.23 times more likely to practice physical distance than their counterparts [AOR = 3.23; 95% CI = (1.46–9.03)] (Table 6).

Discussion

This study assessed knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19 prevention methods among hypertensive patients in North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia. The study finding indicated that around sixty percent of the respondents had good knowledge of the coronavirus. This finding was lower than the study accompanied in Rwanda,18 India,19 Ambo,11 Mizan-Aman town,20 Addis Zemen hospitals, Ethiopia,12 and Arba Minch town Ethiopia.21 The discrepancy may be due to differences in the level of education and access to the source of information. In this study, more than half of the participants do not attend formal education. The study conducted in India among people with diabetes mellitus showed that the level of education has a significant relationship with COVID-19 knowledge.19 On the contrary, this finding was higher than the study conducted on Ethiopians.22 This inconsistency could be attributed to differences in the instruments used to assess participant knowledge, as well as differences in the study population and study periods. The previous study was conducted on a national scale, and the majority of participants (69.7%) were urban residents.

Our study identified that 324 (90.0%) participants knew the transmission of coronavirus person-to-person. This finding was lower than the study conducted in India among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.19 This inconsistency could be attributed to differences in education levels and study populations. The previous study included young adults aged 18–30, with the majority of participants enrolled in formal education. In the current study, approximately half of the participants were rural residents who were not enrolled in formal education. In contrast, the finding was higher than that conducted in Sidama regional state, Ethiopia.23 The discrepancy may occur due to differences in the study population and study design.

This study showed that 199 (55.3%) participants knew the sign and symptoms of the coronavirus specifically, 299 (83.1%) fever, 291 (80.8%) cough, 174 (47.3%) shortness of breath, 114 (31.7%) sore throat. This finding was lower than the study accompanied in Pakistan,24 China,25 Mizan-Aman town, Ethiopia,20 Jimma University Medical Centers, Ethiopia,26 Sidama, Ethiopia,23 and Addis Zemen hospital, Ethiopia.12 The conceivable justification for the discrepancy may be due to variations in the respondent’s education level, accessing the source of information, and study periods.

We found that 286 (79.4%), 283 (78.6%) of study participants knew that chronic disease patients and older people were more at risk of developing severe types of coronavirus, respectively. This finding was relatively similar to a study conducted in the Ambo health facility, Ethiopia.11 The similarity could be due to the uniformity of the study population or both studies were conducted on patients with chronic disease. This result was higher than the survey conducted in Arba Minch town, Ethiopia,21 and Ethiopians.22 The conceivable justification for the variance might be due to a difference in the study population. The previous study was carried out across all communities. The current study was conducted on hypertension patients, who were more aware of COVID-19 as a result of frequent contact with health care professionals during medical follow-up. Furthermore, the national media disseminated various health information focusing on the effect of COVID-19 on patients with chronic diseases. However, this finding was less than the survey accompanied in Pakistan among diabetes mellitus patients.24 This inconsistency may be due to the difference in the educational status of the study participants and the socioeconomic status of the community.

We found that 199 (55.3%) study participants had a favorable attitude towards coronavirus prevention methods. This result was less than the study conducted on Ethiopian residents,27 Dessie and Kombolcha town residents, Ethiopia,28 and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.29 The discrepancies could be attributed to differences in study participants, study period, and access to the source of information. The previous study was conducted among town communities, and when compared to rural communities, the probability of accessing health information disseminated through national media was high. Eighty-two percent of the participants believe that following the recommendations of health care providers decreases the risk of COVID-19. This finding is similar to the study conducted in Sidama regional state, Ethiopia23 and Ambo health facility, Ethiopia.23 We believe that a positive attitude was very important to develop good practice, so health educators should focus on behavioral change communication to increase the community’s attitude and practice toward coronavirus prevention.

The study finding showed that around fifty-four percent of the respondents practice coronavirus disease 2019 prevention methods. This finding was slightly similar to a study conducted in an Ambo health facility, Ethiopia,11 and the regional state of Sidama, Ethiopia.23 The similarity may be due to the uniformity of the study participant and the socio-economic characteristic of the community. But it was higher than the study conducted by Ethiopian residents,27 and Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.30 This discrepancy could be due to a difference in methodology (study setting, data collection period, and study population). On the contrary, this finding was lower than the study conducted in Rwanda,18 Arba Minch,21 and Dessie and Kombolcha town residence, Ethiopia.28 The disparities could be attributed to differences in study participants’ access to health information. The previous study was conducted among the town community; when compared to the rural community, the probability of accessing health information disseminated through national and local media was high.

Practicing prevention measures such as handwashing with water and soap, mask-wearing, maintaining physical distance, and using sanitizers were paramount for pandemic mitigation.31 However, our result showed that 314 (87.2%) of the respondents washed their hands. This result was higher than the survey conducted in an Ambo health facility, Ethiopia,11 Jimma University Medical Center, Ethiopia,26 Addis Zemen hospital, Ethiopia,12 Arba Minch town, Ethiopia,21 and residents of Ethiopia.27 On the contrary, this result was less than the survey conducted in the Philippines,32 and Pakistan.24 The resulting discrepancy may be due to the difference in educational status, access to the source of information, or socioeconomic status of the community. In the current study, around 52% of the participants did not attend formal education, and about half of the participants lived in rural areas, so the probability of accessing the media was very low due to poor infrastructure in the counter.

Two hundred ninety-five (81.9%) of the respondents wore a mask and glove to prevent the virus. This finding was higher than the study accompanied at JUMC, Ethiopia,26 Addis Zemen hospital, Ethiopia,12 residents of Ethiopia,27 and Arba Minch town, Ethiopia.21 One possible explanation for the discrepancies is a difference in the data collection period. The current study was carried out after a significant amount of COVID-19-related information was disseminated at the national and local levels. In contrast, this finding was less than a study conducted at Pakistan,24 and Ataye district hospital, Ethiopia.33 The differences in the findings could be attributed to differences in the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics. The current study found that the majority of participants were rural residents with limited access to COVID-19 health information disseminated at the national and local levels.

Around ninety percent of the participants maintain physical distance to prevent coronavirus. This result was higher than the study conducted at Pakistan,24 Ethiopians,22 Addis Zemen hospital, Ethiopia,12 Jimma University Medical Center, Ethiopia,26 and residents of Ethiopia.27 The possible justification for the discrepancies could be due to a difference in data collection time. The current study was carried out after a significant amount of COVID-19-related information had been disseminated at the national and local levels. On the contrary, this finding was less than a study conducted at an Ataye district hospital, Ethiopia.33 The rational justification for the inconsistency may be due to differences in the study population, education status, and study periods. The previous study was conducted among hospital visitors, but the current study was conducted among hypertension patients who had to follow up in a public hospital. Half of the participants in the current study lived in rural areas and do not attend formal education.

Our study showed that participants who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly were significantly associated with sanitizer. This finding was in line with the study accompanied at Addis Zemen hospital, Ethiopia.12 The rational justification for this finding was that the majority of Ethiopians received less than 2000 Ethiopian Birr per month. Salale University and other sponsors distributed sanitizers (alcohol hand rubs) to the low-income residents of the North Shoa zone. This action may lead to an increase in the use of sanitizers.

Also, respondents who followed the electronic news media were significantly associated with the use of sanitizer. In Ethiopia, the minister of health distributed updated information on coronavirus disease through national electronic news media.

Our study finding indicated that participants who had a favorable attitude toward COVID-19 prevention practices were significantly associated with mask wear. According to health promotion science, a person who developed a favorable attitude towards something practices it easily.34 Based on this, a person who develops a favorable attitude toward the COVID-19 prevention method easily applied the coronavirus prevention method. Participants who received less than two thousand Ethiopian Birr were significantly associated with physical distance maintenance. The majority of Ethiopians earned less than 2000 ETB per month, and most participants might be preferred physical distance because it was more cost-effective than other preventive methods.

Strength and Limitation of the Study

This study had different strengths; first, the study was conducted among the at-risk group (hypertension patients), second, the study included all hospitals found in North Shoa, and third, the researchers tried to avoid different biases by using different methods. On the contrary, the study had different limitations first nature study design or cross-sectional study, second, the tool used to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice were not standard, third this study was conducted in one area, so it is not generalized to all hypertension patients living in Ethiopia.

Conclusions

Generally, this study finding indicated that about 58% of the participants had good knowledge of COVID-19, 55% of the respondents had developed a positive attitude towards COVID-19 prevention methods, and 58% of the participants practiced COVID-19 prevention methods. Respondents who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly and respondents who followed electronic news media were significantly associated with the use of sanitizers, respondents who had a favorable attitude toward the coronavirus disease 19 prevention method were significantly associated with mask wear, and respondents who received less than two thousand Ethiopian birrs monthly were significantly associated with maintaining a physical distance. Therefore, increasing knowledge, attitude, and practice of coronavirus disease 19 among hypertension patients requires a coordinated effort from government, non-government and health professionals. The Ethiopian health minister should continue to distribute updated information through social media and mass media in collaboration with different stakeholders. Finally, the health professional who works in chronic outpatient departments should provide health education on COVID-19 prevention methods to patients with hypertension.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Salale University Ethics Review Committee approved the ethical clearance of written consent on 1 May 2020 with Ref. No. SLUERC/050/2020. A support letter was obtained from the North Showa Zone Health Bureau and official permission was obtained from the selected hospitals. Before starting the interview, the respondents were informed of the purpose of the study and how their data were used. Written consent was obtained from the study participants. The privacy and confidentiality of the study participants were maintained by excluding their names from the questionnaire and keeping their data in a secure place.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the conception, design of the study, execution, and acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation. All authors participated in the writing, review, or critical review of the article; gave their final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article was submitted; and agreed to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The Salale University supports this research work. The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. MacKenzie JS, Smith DW. COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don’t. Microbiol Aust. 2020;41(1):45–50. doi:10.1071/MA20013

2. ECDC. Covid-19-rapid-risk-assessment-Coronavirus-disease-2019-Eighth-Update-8-April-2020. Eur Cent Dis Control Prev. 2020;2019(4):1–39.

3. Ghosh A, Arora B, Gupta R, Anoop S, Misra A. Effects of nationwide lockdown during COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle and other medical issues of patients with type 2 diabetes in north India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):917–920. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.044

4. Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9

5. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report – 106 Data; 2020.

6. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

7. Raghupathi W, Raghupathi V. An empirical study of chronic diseases in the United States: a visual analytics approach to public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):10–12. doi:10.3390/ijerph15030431

8. Surveillances V. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–151.

9. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Articles Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;6736(3):1054–1062.

10. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

11. Melesie Taye G, Bose L, Beressa TB, et al. COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and prevention practices among people with hypertension and diabetes mellitus attending public health facilities in Ambo, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4203–4214. doi:10.2147/IDR.S283999

12. Akalu Y, Ayelign B, Molla MD. Knowledge, Attitude and practice towards COVID-19 among chronic disease patients at Addis Zemen Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1949–1960. doi:10.2147/IDR.S258736

13. Chuka A, Gutema BT, Ayele G, Megersa ND, Melketsedik ZA, Zewdie TH. Prevalence of hypertension and associated factors among adult residents in Arba Minch Health and demographic surveillance site, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237333. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237333.

14. Kibret KT, Mesfin YM. Prevalence of hypertension in Ethiopia: a systematic meta-analysis. Public Health Rev. 2015;36(1). doi:10.1186/s40985-015-0014-z

15. Deriba BS, Geleta TA, Beyane RS, Mohammed A, Tesema M, Jemal K. Patient satisfaction and associated factors during COVID-19 pandemic in North Shoa health care facilities. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1923–1934. doi:10.2147/PPA.S276254

16. Erfani A, Shahriarirad R, Ranjbar K, Alireza Mirahmadizadeh MM. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a population-based survey in Iran. Kbs news; 2020; Available from: http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=4355861.

17. Hussain A, Garima T, Singh BM, Ram R, Tripti RP. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Nepalese Residents: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Asian J Med Sci. 2020;11(3):6–11. doi:10.3126/ajms.v11i3.28485

18. Iradukunda PG, Pierre G, Muhozi V, Denhere K, Dzinamarira T. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among people living with HIV/AIDS in Kigali, Rwanda. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):245–250. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00938-1.

19. Pal R, Yadav U, Grover S, Saboo B, Verma A, Bhadada SK. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among young adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus amid the nationwide lockdown in India: a cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108344. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108344

20. Bekele D, Tolossa T, Tsegaye R, Teshome W. Community’s knowledge of COVID-19 and its associated factors in Mizan-Aman Town, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020. bioRxiv. 2020;13:507–513.

21. Nigussie TF, Azmach NN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia. Glob Sci J. 2020;8:1283–1307.

22. Negera E, Demissie TM, Tafess K. Inadequate level of knowledge, mixed outlook and poor adherence to COVID-19 prevention guideline among Ethiopians. bioRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.07.22.215590

23. Yoseph A, Tamiso A, Ejeso A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 pandemic among adult population in Sidama Regional State, Southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):1–19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246283

24. Ajay K, Hamza I, Deepika K, et al. Knowledge & Awareness about COVID-19 and the practice of respiratory hygiene and other preventive measures among patients with diabetes mellitus in Pakistan. Eur Sci J. 2020;16(12):53–62.

25. Zhong B-L, Luo W, Li H-M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745–1752. doi:10.7150/ijbs.45221

26. Kebede Y, Yitayih Y, Birhanu Z, Mekonen S, Ambelu A. Knowledge, perceptions and preventive practices towards COVID-19 early in the outbreak among Jimma university medical center visitors, Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233744

27. Bekele D, Tolossa T, Tsegaye R, Teshome W. The knowledge and practice towards COVID-19 pandemic prevention among residents of Ethiopia. An online cross-sectional study. bioRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.06.01.127381

28. Muluneh Kassa A, Gebre Bogale G, Mekonen AM. Level of perceived attitude and practice and associated factors towards the prevention of the COVID-19 epidemic among residents of Dessie and Kombolcha Town administrations: a population-based survey. Res Rep Trop Med. 2020;11:129–139. doi:10.2147/RRTM.S283043

29. Desalegn Z, Deyessa N, Teka B, et al. COVID-19 and the public response: knowledge, attitude and practice of the public in mitigating the pandemic in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244780

30. Amsalu B, Guta A, Seyoum Z, et al. Practice of COVID-19 prevention measures and associated factors among residents of Dire DAWA city, eastern Ethiopia: community-based study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:219–228. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S292409

31. FMOH. National comprehensive COVID19 management handbook; 2020. Available from: https://covidlawlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/National-Comprehensive-COVID19-Management-Handbook.pdf.

32. Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: a cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):1. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.011007

33. Gebretsadik D, Ahmed N, Kebede E, Gebremicheal S, Belete MA, Adane M. Knowledge, attitude, practice towards COVID-19 pandemic and its prevalence among hospital visitors at Ataye district hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):1–19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246154

34. Kumar S, Preetha GS. Health promotion: an effective tool for global health. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37(3):5. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.94009

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.