Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 9

Effectiveness of a life story work program on older adults with intellectual disabilities

Authors Bai X, Ho D, Fung K, Tang L, He M, Young KW , Ho F, Kwok T

Received 25 October 2013

Accepted for publication 14 December 2013

Published 31 October 2014 Volume 2014:9 Pages 1865—1872

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S56617

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Xue Bai,1,2 Daniel WH Ho,2 Karen Fung,3 Lily Tang,3 Moon He,3 Kim Wan Young,4 Florence Ho,2 Timothy Kwok2,5

1Department of Applied Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong; 2Jockey Club Centre for Positive Ageing, Shatin, Hong Kong; 3Hong Chi Association, Hong Kong; 4Department of Social Work, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong; 5Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Objective: This study examines the effectiveness of a life story work program (LSWp) in older adults with mild-to-moderate levels of intellectual disability (ID).

Methods: Using a quasiexperimental design, this study assigned 60 older adults who were between 50–90 years old with mild-to-moderate levels of ID to receive either the LSWp (intervention group, N=32) or usual activities (control group, N=28) during a period of 6 months. Evaluation was made based on the outcomes assessed by the Mood Interest and Pleasure Questionnaire, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, and the Personal Well-being Index – ID.

Results and conclusion: LSWp shows potential for improving the quality of life and preventing the loss of interest and pleasure in older adults with ID. It also shows promise in enhancing their socialization skills. Patients with better communication abilities seemed to benefit more from the LSWp.

Keywords: life story work, life story book, intellectual disabilities, older adults, effectiveness

Introduction

There is an increasing recognition of comorbidity between intellectual disability (ID) and mental health problems, emotional disorders, and deficits in socialization skills.1–3 Literature reveals that the aging process commences younger in people with ID at approximately 40–50 years of age.4 As the previously mentioned problems may further lead to long-term health conditions and mortality,5 effective psychosocial interventions need to be developed for older adults with ID – in addition to the pharmacological treatment.

Life story work (LSW) is:

The construction, or reconstruction of an individual’s life-story and involves the integration of the individual’s internal process, as well as the relationships and values with the family, community, and culture in which the individual has developed.6

It creates an opportunity for the person to tell others about their past experiences and then use this life story to benefit them in their present situation.7,8 A variety of forms (book, digital video disc, or collection of personal items) can be used, and the content may contain photographs, written biographies, drawings, art pieces, and other aids for understanding a person’s own memorable experiences.

The LSW program (p) – in particular, life story book – was originally applied to children who were under adoption and foster care services.9 It helped children to develop a sense of identity and continuity in the new setting. LSW was then modified and introduced to a variety of different settings, including children with prior exposure to trauma, people with long-term illnesses,10 older people with or without dementia,11 and – recently – people with intellectual disabilities.12,13 Our past experience and relationships shape our identity and make us who are today.14 This also applies to people with ID and LSWp as a way of keeping their past history alive.

There is evidence that LSWp may encourage people with ID to present and express themselves13 and, hence, improve communication and relationships.15,16 Therefore, LSWp is like a bridge to create connections among clients, family caregivers, and support workers.17,18 Research also indicates that LSWp has a positive impact on participants’ mood. This is especially important for older adults with ID, who are at an increased risk of having mood disorders, particularly depression.19

Similar to other aging people, older adults with ID carry with them many unpleasant past life events and face a great deal of unexpected changes, which they may not be able to cope with.20,21 They also have more difficulties in developing and maintaining a stable social support network,22 which is an essential element in fighting mood problems.23

Older adults with ID are predisposed to have reduced subjective well-being, given their physical disabilities and related psychological stress.24 However, with a strengthened sense of identity, improved social interaction, and increased pleasure and enjoyment about life, it is reasonable to expect that LSWp may enhance the participants’ quality of life (QOL) by engaging them in an appropriate level of activities and contacts.25–27 Hence, it is hypothesized that LSWp, when applied to older adults with ID, will have a positive impact on their mood, socialization, and – ultimately – their QOL.

Most studies on LSW in health and social care have adopted a qualitative approach. Thus, the evidence on the use of LSWp is immature, and there is a great need for quantitative research evidence to substantiate the potential value of LSW and other cognitive behavioral treatments for patients with ID,6,8,28 especially for people with ID.16 In addition, to our knowledge, there are very few LSWp studies on older adults with ID that have a well-established protocol tailor-made to them, despite their marked disparity from the norm.

To address these issues, the present study aimed to develop a training protocol of LSWp especially designed for older adults with mild-to-moderate levels of ID and to evaluate the effectiveness of LSW in this group of older adults on enhancing mood, socialization, and QOL from a quantitative perspective.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from nine hostels, day service centers, and sheltered workshops of the Hong Chi Association. The inclusion criteria were: 1) >50 years of age; 2) mild-to-moderate grade ID, according to the service admission record in their personal case files; and 3) without severe psychiatric disorder or behavioral problem. Gaining informed consent from participants with ID is quite challenging. It is suggested that gaining person-centered consent from such participants.29 This was achieved in this study via an ongoing evaluation of both the verbal and nonverbal cues of the participant during the research process, alongside written consent obtained from the guardian of the participant. Only participants with both their guardians’ written informed consent and those who agreed to participate in the program joined the study.

This study complied with the ethical standard stipulated by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong and ethical approval was granted prior to the data collection.

Study design

This research was commissioned by the Hong Chi Association. The study was conducted from April–December 2011. A quasiexperimental research design was adopted. Participants were assigned to either the intervention group (N=32) or the control group (N=28). The intervention group received the LSWp intervention led by trained LSWp instructors, in addition to their usual daily activities for approximately 6 months. The control group received their usual activities (ie, training on self-care and daily living skills, basic work skill training, activities that developed their hobbies and interests, physical exercises to maintain or strengthen their physical fitness, vocational training in a sheltered environment) during this period. Assessments on the participants’ mood, socialization, and QOL were conducted at baseline and immediately after the intervention.

Content of the LSWp

The protocol of LSWp for older people without ID could not fit the special needs of population with ID. Therefore, a group of clinical psychologists developed a life story book protocol which was designed specifically for this population. In developing this protocol, the following recommendations were taken into consideration: 1) the effective features of a life story intervention design for nursing home residents; and 2) suggestions on the best format for compiling life history resources for older people living in institutional settings.16,30

This life story book protocol consisted of 16 structured one-to-one or group sessions, each lasting for 1.5–2 hours. The entire program spanned a period of approximately 6 months. It comprised a series of activities of various psychosocial elements, such as field visits, outings, production of life story book with photos, presentation, group sharing, and collecting feedback from the caregiver. LSWp instructors work with participants and their family members to collect information and photos that tell the participants’ life stories. LSWp instructors also help participants to express their feelings on their life stories in a caring and accepting atmosphere. Participants are encouraged to use the life story books to share their life stories and achievements with other people. Participants were guided by trained LSWp instructors, who were experienced tutors for people with ID and received training and regular supervision from the clinical psychologists. The protocol provided step-by-step guidelines for the instructors to produce an individualized life story book for each client. The life story book enabled clients to gather current information about themselves (the present) and their history (the past). Moreover, it was a useful tool that could assist the clients to express themselves and “tell their own story” to people around them.

Table 1 summarizes the organization of the LSWp. At the end of the program, each participant will have a personalized life story book that includes the recording of significant people, places, and events for themselves (Table 1).

| Table 1 Summary for the content of LSWp |

Measurement

Validated assessment tools were used to collect data for both intervention and control groups at both pretest and posttest periods. As mood, socialization, and QOL were the outcomes of interest, corresponding assessment tools of Mood Interest and Pleasure Questionnaire (MIPQ),31 Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition (Vineland-II),32 and Personal Well-being Index – Intellectual Disability (Cantonese), third edition (PWI-ID),33 were used respectively. These standardized measurements were chosen as the most appropriate to detect any change in the outcomes of interest for the subjects over the study period. The selected assessment tools demonstrate good reliability and validity. For the purpose of this study, the analysis of Vineland-II mainly focused on the socialization domain, while the communication abilities were perceived as a background and independent variable.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Independent samples t-tests (and chi-square when appropriate) were used to compare demographic characteristics between the control and intervention groups at baseline. Two-way repeated measures of analysis of variance was further used to examine the effectiveness of the LSWp.

The difference in each function or well-being was calculated by subtracting participants’ score measured at baseline from their score measured 2 weeks after the intervention. Independent samples t-tests were further conducted to compare the direction and magnitude of change between the control and intervention groups.

Results

Demographics and baseline measures

Table 2 summarizes the baseline demographics of the participants. A total of 60 participants with ID were recruited into the study and were assigned to either the LSWp intervention group (N=32) or control group (N=28). Results showed that there were no significant differences between the control and intervention groups in terms of demographic factors, including age, sex, education level, communication abilities, marital status, and types of services received. Similarly, no significant differences were detected between the two groups on baseline measurements of personal well-being, mood, interest, and pleasure or adaptive behavior on socialization, as measured by the PWI, MIPQ, and Vineland-II scales, respectively. The LSWp had the potential to prevent the deterioration of mood (as measured by MIPQ) of older adults with ID (Table 2).

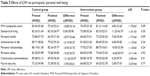

Results of repeated measures analysis of variance showed a marginally significant main effect of time (P=0.07), but the main effect of intervention/control group on the MIPQ score was insignificant (P=0.85). The overall interaction effect of time and intervention was also found to be marginally significant (P=0.09). Further analysis showed that the mean MIPQ score declined from 67.36–62.27 in the control group; whereas, the mean MIPQ score for the intervention group remained almost the same from 65.62–65.35, indicating the effectiveness of LSWp in preventing the negative change in mood, interest, and pleasure of the participants. Independent samples t-tests were further conducted on the mean difference in the subdomains of MIPQ between the control and the intervention groups (Table 3). There was a significant difference in the subdomain of “interest” and “pleasure” (P=0.04), while no differences were evident in other domains. The LSWp showed promise in improving the socialization skills (as measured by Vineland-II) of older adults with ID (Table 3).

Results of repeated measures analysis of variance showed no main effect of time (P=0.54) or intervention/control group (P=0.58) on the socialization skills. Similarly, the overall interaction effect of time and intervention was not significant (P=0.56). Independent samples t-tests were also conducted on the mean difference in adaptive behaviors and other subscales of the Vineland-II scale between the control and the intervention groups, but there were no significant differences. As stated in Table 4, concerning their socialization skills, the intervention group improved a little (ΔM =3.19; SD =20.66) while their counterparts in the control group remained the same (ΔM =0.07; SD =19.32). However, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. The LSWp enhanced QOL (as measured by the PWI-ID) of older adults with ID (Table 4).

| Table 4 Effects of LSW on participants’ adaptive behaviors |

Results of repeated measures analysis of variance showed no main effect of time (P=0.77) or intervention/control group (P=0.96) on the PWI score. But the overall interaction effect of time and intervention was marginally significant (P=0.09). The mean PWI score declined from 82.04 to 76.24 in the control group while that for the intervention group increased from 75.24 to 81.31, indicating the LSWp tended to enhance the QOL among older adults with ID. The mean scores of both the intervention and control groups were higher than that of the norm in Hong Kong which is 63.99.33

Independent samples t-tests were further conducted on the change of mean (ΔM) in different PWI life domains between the control and the intervention groups (Table 5). Particularly, the personal health status of participants in the intervention group improved after receiving the LSW treatment (ΔM =7.60), but it deteriorated in the control group (ΔM =−8.57). The difference between the two groups was marginally significant (P=0.09). A similar pattern was observed in the community-connectedness domain. There was marked improvement concerning community-connectedness among the intervention group (ΔM =6.20; standard deviation [SD] =29.91); whereas, a decrease in community-connectedness was detected in the control group (ΔM =−21.43; SD =34.97). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.01; Table 5).

| Table 5 Effects of LSW on participants’ personal well-being |

Although there were no significant differences in the other five life domains between the control and the intervention group, the outcome of the intervention group seemed to be better than that of the control group in all of these domains, as demonstrated by the mean differences (Table 5). The effectiveness of LSW tended to vary, depending on the participants’ communication abilities.

To examine whether the effectiveness of LSWp was dependent on the participants’ communication abilities, we divided the participants who received the intervention into two groups based on their communication abilities. A mean cut-off score of 27.7 (according to the Vineland-II manual on adults with moderate-grade mental retardation) was used to categorize participants into a low communication group (mean score, ≤27.7), and a high communication group (mean score, >27.7). As a result, 18 participants were assigned to the low communication group, and 14 participants were assigned to the high communication group.

Independent samples t-tests were conducted on the change of mean (ΔM) in different outcome variables between the low and high communication groups. Compared to the low communication score group (ΔM =−0.95; SD =29.06), The LSWp seemed to be more effective in improving the PWI of the group with the higher communication score (ΔM =10.60; SD =15.89) and its subdomains except for personal safety – although this did not reach statistical significance. A similar pattern was observed for the socialization skills (low communication score group, ΔM =0.44, SD =6.30; high communication score group, ΔM =6.71, SD =30.69). However, all of these observed differences did not reach statistical significance, partly due to a relatively small sample in our study.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study represents one of the first attempts, using quantitative assessments, to evaluate the effectiveness of LSWp in enhancing mood, socialization, and QOL in older adults with ID. The results of the study showed that our LSWp was generally effective in improving QOL. It had the potential to prevent the deterioration of mood and showed promise in improving the socialization skills in older adults with ID. In addition, we also found that the effectiveness of LSW tended to vary, depending on the participants’ communication abilities. Patients with better communication abilities seemed to benefit more from the LSWp.

First, consistent with the results of the previous studies, our LSWp improved the personal well-being of the participants, and it especially enhanced participants’ perceived personal health and sense of community-connectedness.8,34 Since there is evidence that happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health,35 and people’s self-rated health status is significantly and positively correlated with their actual physical and mental health, which may further contribute to better QOL, the improvement of the participants’ perceived personal health was quite a desirable outcome of LSWp.36 To some extent, it indicated participants’ ameliorated health status and QOL after receiving LSWp.

Second, although a significant improvement in mood was not detected in the participants of LSWp, the results were encouraging in that, compared to the control group who experienced a drop in the MIPQ score, those who participated in the LSWp had a relatively stable mood reflected by the MIPQ score. The LSWp participants were more emotionally stable, showed interest, and actively participated in the LSWp. A previous study has shown that emotional competence is positively and significantly associated with happiness and life satisfaction.37 As a matter of fact, it has been shown that people with ID are more likely to suffer from emotional disorders,1,19 and the severity of emotional problems including depressed mood and the loss of interest was positively correlated with age.5,38 These findings partly explain why a natural decline in the MIPQ score was detected in the control group in the present study. Since previous studies have also found that emotional disorders may further affect long-term health conditions and mortality, effective interventions are needed.5 This study discovered the potential of our LSWp to act as a protective factor in preventing the deterioration of mood in people with ID.

Third, results showed a positive trend of improvement among subjects in the intervention group in terms of their socialization skills, although this was not statistically significant. It could be that participants need some time to practice their improved social skills and, therefore, the improvement may not be immediately observable. In the program, it was believed that the tailor-made life story book with photos from LSW could assist the recall of past memories of the participants, help them to express themselves, and promote sharing with others. This aspect of change could be regarded as the improvement in socialization skills and community-connectedness. To some extent, the stronger sense of community-connectedness, the increased interest and pleasure, and the improved socialization skills can be perceived as enhanced participation, which has been found to be a valuable experience for people with different types of disabilities.39

Last – but not least – participants with better communication skills seemed to benefit more from the program. Compared to the group with a lower communication score, the LSWp seemed to be more effective for the high communication group in improving their socialization skills and QOL although statistical significance was not reached. A possible explanation was that those who had better expressive and comprehension skills were more actively involved in the LSWp as compared to those with relatively limited verbal abilities.

Limitations

Although the current study represents the first attempt to comprehensively and quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of LSWp on older adults with ID, the results might be affected by the relatively small sample size. In addition, as all of the participants were recruited from the same rehabilitation organization and the intervention and control group were not equally distributed in their living conditions for the ease of administration in the delivery of LSWp, this might weaken the rigor and generalizability of the findings. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to provide more convincing evidence.

Furthermore, only the immediate effect of LSWp was examined. It would be better if regular booster trainings could be provided after the completion of the LSW, so that participants could update their LSW and refresh their memory and learning. The long-term effect of LSW could be further examined if booster trainings were incorporated into the program.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Hong Chi Association in Hong Kong. The authors want to extend their thanks to Dr Belinda Garner from the Faculty of Health and Social Sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University who assisted in the proofreading of this article. The authors also would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Tonge B, Einfeld S. Intellectual disability and psychopathology in Australian children. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 1991;17(2):155–167. | ||

Bouras N, Holt G. Mental health services for adults with learning disabilities. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184(4):291–292. | ||

Myrbakk E, von Tetzchner S. Psychiatric disorders and behavior problems in people with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2008;29(4):316–332. | ||

Slevin E, Taggart L, McConkey R, Cousins W, Truesdale-Kennedy M, Dowling S. Supporting people with intellectual disabilities who challenge or who are ageing: a rapid review of evidence. Belfast, Northern Ireland: University of Ulster; 2011. Available from: http://www.cardi.ie/userfiles/Intellectual%20Disability.pdf. Assessed June 10, 2013. | ||

Lavretsky H, Zheng L, Weiner MW, et al. Association of depressed mood and mortality in older adults with and without cognitive impairment in a prospective naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5): 589–597. | ||

Cook–Cottone C, Beck M. A model for life-story work: Facilitating the construction of personal narrative for foster children. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2007;12(4):193–195. | ||

Atkinson D, Jackson M, Walmsley J. Forgotten Lives: Exploring the History of Learning Disability. Kidderminster: British Institute of Learning Disabilities; 1998. | ||

McKeown J, Clarke A, Ingleton C, Ryan T, Repper J. The use of life story work with people with dementia to enhance person-centred care. Int J Older People Nurs. 2010;5(2):148–158. | ||

Ryan T, Walker R. Life Story Work: A Practical Guide to Helping Children Understand Their Past. 3rd ed. London: British Association for Adoption and Fostering; 2007. | ||

Rose R, Philpot T. The Child’s Own Story: Life Story Work with Traumatized Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2005. | ||

Hansebo G, Kihlgren M. Nursing home care: changes after supervision. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(3):269–279. | ||

Hewitt H. Tell it like it is. Learning Disability Practice. 2003;6(8): 18–22. | ||

Meininger HP. Narrative ethics in nursing for persons with intellectual disabilities. Nurs Philos. 2005;6(2):106–118. | ||

Linde C. Life Stories: The Creation of Coherence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. | ||

McKeown J, Clarke A, Repper J. Life story work in health and social care: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55(2):237–247. | ||

Moos I, Björn A. Use of the life story in the institutional care of people with dementia: a review of intervention studies. Ageing Soc. 2006;26(3):431–454. | ||

Batson P, Thorne K, Peak J. Life story work sees the person beyond the dementia a project to evaluate life story work, and how it helped care professionals and family carers as well as people with dementia. Journal of Dementia Care. 2002;10(3):15–17. | ||

Clarke A, Hanson EJ, Ross H. Seeing the person behind the patient: enhancing the care of older people using a biographical approach. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(5):697–706. | ||

Davidson PW, Prasher VP, Janicki MP. Mental Health, Intellectual Disabilities and the Aging Process. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. | ||

Hussain F, Raczka R. Life story work for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1997;25(2):73–76. | ||

van Puyenbroeck JV, Maes B. Reminiscence in ageing people with intellectual disabilities: An exploratory study. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2005;51(100):3–16. | ||

Reynolds WM, Miller KL. Depression and learned helplessness in mentally retarded and nonmentally retarded adolescents: an initial investigation. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1985;6(3):295–306. | ||

Rosenquist JN, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Social network determinants of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(3):273–281. | ||

Viitanen M, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bernspång B, Fugl-Meyer AR. Life satisfaction in long-term survivors after stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1988;20(1):17–24. | ||

Bigby C. Known well by no-one: Trends in the informal social networks of middle-aged and older people with intellectual disability five years after moving to the community. Journal of Intellectual and Development Disability. 2008;33(2):148–157. | ||

Brown RI. Quality of life issues in aging and intellectual disability. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 1993;18(4):219–227. | ||

Dagnan D, Ruddick L, Jones J. A longitudinal study of the quality of life of older people with intellectual disability after leaving hospital. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998;42(Pt 2):112–121. | ||

Nicoll M, Beail N, Saxon D. Cognitive behavioural treatment for anger in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2013;26(1):47–62. | ||

Dewing J. From ritual to relationship: a person-centered approach to consent in qualitative research with older people who have a dementia. Dementia. 2002;1(2):157–171. | ||

Reichman S, Leonard C, Mintz T, Kaizer C, Lisner-Kerbel H. Compiling life history resources for older adults in institutions: development of a guide. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(2):20–28; quiz 55. | ||

Ross E, Oliver C. Preliminary analysis of the psychometric properties of the Mood, Interest and Pleasure Questionnaire (MIPQ) for adults with severe and profound learning disabilities. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003; 42(Pt 1):81–93. | ||

Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Second Edition (Vineland-II) – Survey Interview Form/Caregiver Rating Form. Livonia, MN: Pearson Assessments; 2005. | ||

Cummins RA, Lau ALD. Personal Wellbeing Index – intellectual disability. 3rd ed. Melbourne: School of Psychology, Deakin University; 2005. Cantonese. | ||

van Puyenbroeck J, Maes B. The effect of reminiscence group work on life satisfaction, self-esteem and mood of ageing people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2009;22(1):23–33. | ||

Siahpush M, Spittal M, Singh GK. Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(1):18–26. | ||

Zullig KJ, Valois RF, Drane JW. Adolescent distinctions between quality of life and self-rated health in quality of life research. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:64. | ||

Rey L, Extremera N, Durán A, Ortiz-Tallo M. Subjective quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities: the role of emotional competence on their subjective well-being. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2013;26(2): 146–156. | ||

Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, Corbeau C. Cross-sectional and prospective study of exercise and depressed mood in the elderly: the Rancho Bernardo study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(6):596–603. | ||

Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Whiteneck G, Bogner J, Rodriguez E. What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(19):1445–1460. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.