Back to Journals » ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research » Volume 8

Economic evaluation of obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil in first-line treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Spain

Authors Casado LF, Burgos A, González-Haba E , Loscertales J, Krivasi T, Orofino J, Rubio-Terrés C, Rubio-Rodríguez D

Received 7 June 2016

Accepted for publication 8 July 2016

Published 21 September 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 475—484

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S114524

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Giorgio Colombo

Luis Felipe Casado,1 Amparo Burgos,2 Eva González-Haba,3 Javier Loscertales,4 Tania Krivasi,5 Javier Orofino,6 Carlos Rubio-Terres,7 Darío Rubio-Rodríguez7

1Hematology Department, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain; 2Pharmacy Department, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante, Spain; 3Pharmacy Department, Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain; 4Hematology Deparment, Hospital Universitario De La Princesa, Madrid, Spain; 5Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland; 6Roche Farma SA, Madrid, Spain; 7Health Value, Madrid, Spain

Objective: To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil (GClb) versus rituximab plus chlorambucil (RClb) in the treatment of adults with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and with comorbidities that make them unsuitable for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System.

Methods: A Markov model was developed with three mutually exclusive health states: progression-free survival (with or without treatment), progression, and death. Survival time for the two treatments was modeled based on the results of CLL11 clinical trial and external sources. Each health state was associated with a utility value and direct medical costs. The utilities were obtained from a utility elicitation study conducted in the UK. Costs and general background mortality data were obtained from published Spanish sources. Deterministic and probabilistic analyses were conducted, with a time frame of 20 years. The health outcomes were measured as life years (LYs) gained and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained. Efficiency was measured as the cost per LY or per QALY gained of the most effective regimen.

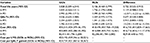

Results: In the deterministic base case analysis, each patient treated with GClb resulted in 0.717 LYs gained and 0.673 QALYs gained versus RClb. The cost per LY and per QALY gained with GClb versus RClb was €23,314 and €24,838, respectively. The results proved stable in most of the univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses, with a probabilistic cost per QALY gained of €24,734 (95% confidence interval: €21,860–28,367).

Conclusion: Using GClb to treat patients with previously untreated CLL for whom full-dose fludarabine-based therapy is unsuitable allows significant gains in terms of LYs and QALYs versus treatment with RClb. Treatment with GClb versus RClb can be regarded as efficient when considered the willingness to pay thresholds commonly used in Spain.

Keywords: chlorambucil, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, cost-effectiveness, obinutuzumab, rituximab

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a chronic lymphoproliferative syndrome and is the most common hematological malignancy in Western countries.1 In Spain, the incidence is estimated at 4.2 and 3.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants a year in males and females, respectively;2 hence, about 1,600 new cases are diagnosed each year. The mean age of CLL patients at diagnosis is ~70 years, and the disease is uncommon in individuals under 65 years of age.2,3 Patients with CLL show a mean survival of up to 10 years.4 The presentation at diagnosis, the genetic and molecular profile, and the clinical course of the disease are so heterogeneous that the approach to treatment depends on the characteristics of both the disease and the patient, particularly on the presence or absence of comorbidities.1 Due to the indolent nature of the disease, it is estimated that approximately one-third of patients with CLL will never require treatment, while the rest will be treated immediately or at an earlier period to 5 years after diagnosis.5

Immunochemotherapy with rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (FCR) is currently the standard therapy in previously young untreated patients in the absence of comorbidities.1 However, many patients with CLL cannot receive FCR due to the excessive toxicity of fludarabine and their physiological conditions.1,6 These patients often receive monotherapy with chlorambucil (Clb) in the presence of severe comorbidities, or a combination of rituximab with Clb (RClb) in the case of patients with moderate comorbidities.1 However, the results of these treatments remain unsatisfactory.1,7,8

Obinutuzumab has recently been marketed in Spain for administration in combination with Clb (GClb) in adults with previously untreated CLL and with comorbidities which make them unsuitable for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy.9 Obinutuzumab is a recombinant monoclonal humanized anti-CD20 immunoglobulin G1 isotype type II antibody modified through glycoengineering; it targets the CD20 protein present in B-lymphocytes, inducing cell death.9 In 2012, obinutuzumab was granted orphan designation for the treatment of CLL by the Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products of the European Medicines Agency.10 The efficacy and safety of GClb was demonstrated in the CLL11 trial, which compared GClb with RClb or Clb monotherapy in 781 patients with previously untreated CLL for whom full-dose fludarabine-based therapy was contraindicated because of comorbidities.7

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of treatment with GClb versus RClb in adults with previously untreated CLL and with comorbidities that make them unsuitable for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (NHS).

Methods

Economic model

A Markov model was developed with three mutually exclusive health states: progression-free survival (PFS) (with or without treatment), progression, and death (Figure 1). This was considered to be the most appropriate structure, which has been frequently used in the evaluation of cancer treatments, according to a systematic review of the medical and economic literature.11–14 Each health state was assigned a specific cost and utility value (patient-perceived quality of life).

| Figure 1 Markov model structure. Abbreviation: PFS, progression-free survival. |

The model simulated a cohort of CLL patients based on the CLL11 trial, who start in the PFS state and during the course of the simulation, they can either remain in the PFS state or transit toward the other states (progression or death). The PFS state separately considered patients “with treatment” and patients “without treatment” in order to account for differences in treatment administration both in economic terms and in patients’ quality of life during and after treatment.

It was assumed that transitions between the Markov states would occur every 7 days (model cycle length); accordingly, each 28-day GClb or RClb treatment cycle would comprise four cycles of the model. Patients received up to six treatment cycles, unless disease progression was previously confirmed or the treatment had to be discontinued because of toxicity, according to the CLL11 trial.7

Univariate deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed (modifying one variable in each analysis), together with probabilistic analyses (Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000 analyses). For the probabilistic analyses, the following variables were sampled on a random basis: utilities (beta distribution), PFS (Weibull distribution), sampled using Cholesky decomposition15 and postprogression survival (exponential distribution), all costs including adverse events (AEs), monthly cost of supportive therapy in PFS and progression, and the costs of administration of the medicines, as well as the rate of AEs (log-normal distribution). The economic model was generated using Microsoft Excel.

A panel of experts composed of two hematologists (coauthors LFC and JL) and two hospital pharmacists (coauthors AB and EG-H) validated all the premises of the model.

Population

The initial age of the modeled CLL cohort was 71.7 years, according to the mean age of patients in the CLL11 clinical trial.7 The information on mean body weight (72.2 kg) and height (162.4 cm) was obtained from the Spanish Ministry of Health (MSSSI) databases.16 The mean body surface area was calculated based on the Mosteller formula (Table 1). Consent and ethical approval for the use of this data was deemed not necessary by the authors due to no individual patient data being used. All data used are published data.

| Table 1 Variables of the model Notes: All costs are expressed in euros corresponding to February 2016. Panel, panel of clinical experts. aBased on the Mosteller formula: Abbreviations: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; EFP, ex-factory price; GClb, obinutuzumab + chlorambucil; IV, intravenous; PFS, progression-free survival; RClb, rituximab + chlorambucil; RD, Spanish Royal Decree-Law; SmPC, Summaries of Product Characteristics. |

Transition probabilities

Transition probabilities used in the model were derived from the most up-to-date CLL11 clinical information available, corresponding to data cut-off of May 2015.17 The results of the latest data cut analyses showed GClb to be more effective than RClb, with a median PFS of 28.7 and 15.7 months for GClb and RClb, respectively, and a hazard ratio of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.38–0.55; P<0.0001). The time to next antileukemic treatment was 51.1 and 38.2 months for GClb and RClb, respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.57 (95% CI: 0.44–0.74; P<0.0001).17

The probability of remaining in the PFS state was parameterized and extrapolated beyond CLL11 follow-up time using a Weibull distribution. The Weibull distribution was selected since it provided the best fit to the CLL11 PFS data, based on statistical tests such as the Akaike information criterion18 and visual inspection. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using other statistical distributions: exponential, log-logistic, log-normal, gamma, and Gompertz.15 The probability of transiting from PFS to death was the maximum between the death rate during PFS in CLL11 and the Spanish age- and sex-specific mortality. The probability of moving from PFS to progression was then calculated as the complementary probability of remaining in the PFS state and of death from PFS.

Due to the immaturity of the overall survival (OS) data of the CLL11 trial at the time of data cut-off (median OS was not reached),17 the probability of transiting from progression to death was obtained from the CLL5, a Phase III clinical trial,19 which compared fludarabine versus Clb as the first-line therapy in patients with CLL. The probability of death after progression was based on an exponential function according to the Akaike information criterion and visual inspection. Age at progression was used as a covariate to account for age differences in the populations. Sensitivity analysis on this input was performed using the CLL8 trial, which compared FCR versus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide as the first-line therapy in patients with CLL.20 The projection of OS was then based on the extrapolated PFS and postprogression survival curves. Predicted survival curves are depicted in Figure 2.

Utilities

The health state utilities were obtained from a utility elicitation study involving 100 subjects in the UK, based on the time trade-off method (Table 1).21 The impact of being on/off treatment was accounted for. Differences in the administration route (intravenous [IV] or oral) and hospital visits associated with each treatment were also reflected in the utilities applied in the model. The utilities were used to adjust survival time and obtain the quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for each of the regimens compared. Sensitivity analysis considered the 95% CI for each health state utility value.

Costs

The model considered direct health care costs only, which included drug acquisition, patient follow-up, the management of grade ≥3 AEs, and the cost of the IV administration of the medicines. All costs were obtained from Spanish sources and are reported in euros for the year 2016.22,23

The price considered for obinutuzumab in the base case was the reported ex-factory price (EFP). It should be acknowledged that the price of obinutuzumab is lower than the reported EFP, when charged to the Spanish NHS. This reimbursed price by the NHS is confidential and could not be used in this study. The price considered for rituximab corresponded to the EFP, whereas there is no lower confidential price of rituximab for the NHS. On the other hand, the price of Clb was not publicly available in Spain; therefore, this price was provided by the panel of experts (Table 1).

Sensitivity analyses on the acquisition prices charged to the NHS were carried out for both treatments. Regarding rituximab, a 15% reduction was applied to the EFP (base case) due to application of the Spanish Royal Decree-Law 9/2011 (RD).24 Concerning obinutuzumab, different acquisition cost levels (10% and 20% lower than the base case) were considered, in which case the RD deduction was also applied (4%; due to its status as an orphan drug) (Table 1).24

With regard to the doses of GClb and RClb, the model considered the mean doses recorded in the CLL11 trial, accounting for dropout, treatment discontinuation, or dose reduction, since this could be what might be expected in clinical practice. Maximum vial sharing was assumed. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the doses and duration of each treatment as specified in the corresponding Summary of Product Characteristics (Table 1).

AEs of grade 3 or higher severity were determined from the CLL11 trial. Those with an incidence of 3% or higher in any treatment arm were included, unless they were irrelevant in terms of costs incurred. Costs were obtained from two Spanish sources.22,23 The cost of IV administration was also taken from a Spanish study.25 With regard to the estimated cost of patient follow-up (supportive care costs), the panel of experts considered that there would be eight visits to the hematologist with GClb and seven with RClb, annually. Sensitivity analyses were performed for the costs of AEs, supportive care, and IV administration, considering estimates ±20% over the base case value (Table 1).

Time horizon

Despite the fact that the mean survival of these patients is 10 years the time horizon considered in the base case was 20 years, since a percentage of CLL patients (about 10%) survive for over 18 years.26,27 This time horizon was in line with previously published cost-effectiveness analysis in the same disease area within the Spanish setting.25 Sensitivity analyses considered a time horizon of 10 and 15 years (Table 1).

Discounting

Annual costs and benefits (life years [LYs] and QALYs) were discounted at 3%, in accordance with the recommendations in Spain.28 Sensitivity analyses considered discounts of 0% and 5% (Table 1).

Presentation of results

The results are presented as cost differences, LYs gained, and QALYs gained per patient treated with GClb versus RClb. The primary study outcome is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), considering the cost per LY and QALY gained with the most effective regimen. The ICER was calculated in the base case deterministic analysis, and all the primary variables of the model were entered in univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses. In the latter case, the ICER is presented as a mean value with a corresponding 95% CI.

Perspective of the analysis

The perspective of the study was that of the Spanish NHS. Consequently, only the direct health care costs were considered.

Results

Deterministic analyses

In the base case, GClb was found to increase lifetime discounted costs by €16,716 for an additional 0.717 LYs and 0.673 QALYs, compared to RClb. This resulted in a cost per LY and per QALY gained of €23,314 and €24,838, respectively (Table 2). The largest part of the costs accrued due to health state costs of the PFS state, as patients spent most of their time in this state and received treatment. The costs in progression disease were similar across the two arms due to the small incremental time spent in this state and the lack of pharmacological treatment costs in this state.

Sensitivity analyses

According to the univariate sensitivity analysis (Table 3), the cost per QALY gained with GClb versus RClb varied between €16,734 (log-normal distribution for PFS) and a maximum of €30,589 (duration of treatment as per Summary of Product Characteristics).

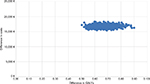

The probabilistic analysis confirmed the base case results. The ICER referred to GClb versus RClb was €23,192 (€19,346–28,521) per LY gained and €24,734 (€21,860–28,367) per QALY gained (Table 4). The impact of the uncertainty upon the outcome of the model is represented in the cost-effectiveness plane (Figure 3), where the 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations were run. The incremental cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Figure 4) showed that 95% of the simulations were below €29,165 per QALY gained and 100% were below €34,432 per QALY gained.

Discussion

The CLL11 clinical trial demonstrated the benefit afforded by GClb versus RClb in terms of efficacy.17 According to the evaluation of the European Medicines Agency, the results obtained with GClb versus RClb are of such a magnitude that they evidence a clear clinical relevance in delaying disease progression and are of evident importance for the patients.29 This study has examined whether these clinical benefits can also be regarded as cost-effective. Two conclusions can be drawn from the results obtained. First, there is a significant gain in QALYs with GClb versus RClb. Specifically, the gain in QALYs for each patient treated with GClb instead of RClb would be 0.673. This difference would have a significant patient impact considering that a clinically relevant gain (the minimum QALY difference the patient is able to perceive) is generally estimated as 0.03 or 0.04 QALYs.30,31 Second, treatment with GClb versus RClb can be regarded as efficient considering the cost-effectiveness thresholds commonly used in Spain (€30,000–45,000).32

Still, the results of the study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. This study utilized a decision-analytic modeling approach, which by definition constitutes a simplified simulation of reality. The model utilized a Markov process, which is the standard method used in cost-effectiveness studies to represent the natural history in various diseases33,34 and the most widely used model for analyzing cost-effectiveness in CLL.35

The main limitation of the analyses was the lack of long-term data in CLL11.17 Although PFS data had reached the median at the time of the last data cut-off, the median OS was not reached for GClb and RClb arm.17 For this reason, OS was projected using longer-term postprogression survival data from CLL5 and CLL8 trials. The same postprogression survival was applied in both arms; this was considered a conservative approach. As a result, the OS Kaplan-Meier curve and the projected OS curve deviated from each other in both arms (Figure 2), which could be explained due to the uncertainty in the tail of the KM curve, population differences across the trials (CLL11, CLL5, CLL8), as well as differences in the progression definitions. Further data from CLL11 would be needed to confirm the tails in the model extrapolations.

It should be, however, acknowledged that the distribution selected to extrapolate PFS (Weibull) had the lowest incremental QALY gain for GClb, compared to the rest of the distributions used in sensitivity analyses (Table 3), while being a key driver of the model results.

Another aspect of the model that must be underscored refers to the price of obinutuzumab. According to the Spanish Royal Decree-Law 16/2012, medicinal products can be prescribed from the NHS according to a reimbursed price or from outside the NHS with the price reported by the marketing pharmaceutical company.36 The reimbursed price by the NHS, which is lower than the reported price, is confidential and is agreed by the MSSSI. For this reason, the economic model could not make use of this reimbursed price and had to resort to the reported price, which is the only published price.37 Since the reimbursed price is lower than the reported (used in the base case) price, the ICER resulting from using the reimbursed price would be lower than that obtained in the base case. In order to try to overcome this limitation, univariate sensitivity analyses were performed, applying different obinutuzumab acquisition levels (10% and 20% lower than the reported price), assuming that the deduction agreed with the MSSSI in establishing the reimbursed price would fall within this interval.

It is important to highlight the fact that the efficacy of obinutuzumab and chlorambucil combination was obtained from an explanatory Phase III clinical trial.7 In addition, patients included in the pivotal clinical trial had very different comorbidities.7 Consequently, it would be of interest to undertake economic analyses of cost-effectiveness of the scheme evaluated for different comorbidities and in the real world.

Lastly, another limitation of our study refers to the utilities employed. These utilities were not obtained from the patients in the CLL11 trial, as would have been desirable, but were derived from a study involving 100 healthy individuals in the UK.21 Nevertheless, the methodology employed (time trade-off method) and the questionnaire used (EuroQol-5D) in this study have been widely used in similar economic models.38–40 As regards to the applicability of the utility data to the Spanish population, a European utility study (Spain included) using the EQ-5D questionnaire revealed greater variability among individuals than among countries,41 thus making the UK-derived estimates, to some extent, appealing to the Spanish setting too.

In order to evaluate the impact of these uncertainties upon the results of the model, we conducted extensive sensitivity analyses, as mentioned previously. Under these analyses, GClb showed favorable cost-effectiveness results and remained within the limits of acceptable willingness to pay thresholds in Spain.

Disclosure

J Orofino was an employee of the company Roche Farma SA, and T Krivasi was an employee of the company F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. at the time of preparation of this manuscript. C Rubio-Terres and D Rubio-Rodríguez received an honorarium from Roche Farma SA in connection with the development of this manuscript. L Felipe Casado, A Burgos, E González-Haba, and J Loscertales do not have any conflicts of interest in this work.

References

García Marco JA, Giraldo Castellano P, López Jiménez J, Ríos Herranz E, Sastre Moral JL, Terol Casterá MJ, Bosch Albareda F. [National guidelines for the management of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sociedad Española de Hematología y Hemoterapia and Grupo Español de Leucemia Linfocítica Crónica]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;141(4):175, e1–e8. Spanish. | ||

Grupo Cooperativo del REL. Resultados del Registro Español de Leucemias (REL) 2002 [Spanish Leukemias Registry Results (REL) 2002]. Madrid: Aula Médica; 2003. Spanish. | ||

González Rodríguez AP, González García E, Fernández Alvarez C, González Huerta AJ, González Rodríguez S. [B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia: epidemiological study and comparison of MDACC and GIMENA pronostic indexes]. Med Clin (Barc). 2009;133(5):161–166. Spanish. | ||

Hernández JA, González M, Hernández JM. [Chronic lymphocytic leukemia]. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;135(4):172–178. Spanish. | ||

Terol MJ. ¿Deben tratarse todos los pacientes con leucemia linfática crónica (LLC) “Sin mutaciones”? ¿Cuándo y cómo? Haematologica (ed. esp.) [Should all patients treated with Chronic lymphatic leukemia(CLL) “No mutations”? When and how?]. 2003;87(Suppl 6):387–392. Spanish. | ||

Shanafelt T. Treatment of older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: key questions and current answers. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:158–167. | ||

Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. | ||

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Medical Review. 2013 [April 23, 2014]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/125486Orig1s000MedR.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016. | ||

Summary of Product Characteristics. Gazyvaro 1,000 mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/es_ES/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002799/WC500171594.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2016. | ||

Recommendation for maintenance of orphan designation at the time of marketing authorisation Gazyvaro (obinutuzumab) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. EMA/COMP/345188/2014 Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products. August 21, 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/orphans/2012/11/human_orphan_001129.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d12b. Accessed February 19, 2016. | ||

Dervaux B, Lenne X, Theis D, et al. Cost effectiveness of oral fludarabine in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: the French case. J Med Econ. 2007;10(4):339–354. | ||

Scott WG, Scott HM. Economic evaluation of third-line treatment with alemtuzumab for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(11):755–764. | ||

Hornberger J, Reyes C, Shewade A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adding rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(2):225–234. | ||

Mittmann N, Isogai PK, Connors JM, Rebeira M, Cheung MC. Economic analysis of alemtuzumab (MabCampath®) in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Open Pharmacoecon Health Econ J. 2012;4(1):18–25. | ||

Briggs A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Decision Modelling for Health Economic Evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. | ||

Atlas de la Sanidad en España. Índice general de Población.Talla y peso medio, según grupo de edad y sexo. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [General Index of Population. Height and Average body weight, by age, group and sex. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality.]. Available from: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/atlas/atlasDatos.htm. Accessed January 19, 2016. Spanish. | ||

Goede V, Fischer K, Bosch F, t al. Updated survival analysis from the CLL11 study: Obinutuzumab versus rituximab in chemoimmunotherapy-treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(23):1733. Poster session presented at 57th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, Orlando, FL. | ||

Cavanaugh JE. 171:290 Model Selection Lecture II: The Akaike Information Criterion. Available from: http://myweb.uiowa.edu/cavaaugh/ms_lec_2_ho.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2016. | ||

Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(16):3382–3391. | ||

Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. | ||

Kosmas CE, Shingler SL, Samanta K, Wiesner C, Moss PA, Becker U, Lloyd AJ. Health state utilities for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: importance of prolonging progression-free survival. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(5):1320–1326. | ||

Isla D, González-Rojas N, Nieves D, Brosa M, Finnern HW. Treatment patterns, use of resources, and costs of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients in Spain: results from a Delphi panel. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13(7):460–471. | ||

Ojeda B, de Sande LM, Casado A, Merino P, Casado MA. Cost-minimisation analysis of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride versus topotecan in the treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer in Spain. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(6):1002–1007. | ||

Listado de medicamentos afectados por las deducciones del Real Decreto-ley 8/2010. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [List of drugs affected by the Royal Decree deductions. Law 8/2010. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality]. Available from: https://www.msssi.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/notasInfor.htm. Accessed March 15, 2016. Spanish. | ||

Casado LF, García JA, Gilsanz F, et al. [Economic evaluation of rituximab added to fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide versus fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia]. Gac Sanit. 2011;25(4):274281. Spanish. | ||

Herring W, Pearson I, Purser M, Nakhaipour HR, Haiderali A, Wolowacz S, Jayasundara K. Cost effectiveness of ofatumumab plus chlorambucil in first-line chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in Canada. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(1):77–90. | ||

Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, Tallman MS, Belch A, Morrison VA, Larson RA. Long-term survival analysis of the North American Intergroup Study C9011 comparing fludarabine (F) and chlorambucil (C) in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2009;114(22):536. | ||

Guía y recomendaciones para la realización y presentación de evaluaciones económicas y análisis de impacto presupuestario de medicamentos en el ámbito de CatSalut [Guidance and recommendations to perform and present economic assessments and budget impact analysis of drugs in CatSalut.]. Barcelona: CatSalut, marzo de 2014. Available from: http://static.correofarmaceutico.com/docs/2014/03/19/guia_cat.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2016. Spanish. | ||

CHMP assessment report. Gazyvaro. EMA/CHMP/231450/2014. May 22, 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002799/human_med_001780.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed January 25, 2016. | ||

Kaplan RM. The minimally clinically important difference in generic utility-based measures. COPD. 2005;2(1):91–97. | ||

Wee HL, Machin D, Loke WC, et al. Assessing differences in utility scores: a comparison of four widely used preference-based instruments. Value Health. 2007;10(4):256–265. | ||

De Cock E, Miravitlles M, Gonzalez J, Azanza P. [Threshold value of the cost for life-years gained by adopting health technologies in Spain: Evidence from a literature review]. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;4(3):97–107. Spanish. | ||

Mar J, Antoñanzas F, Pradas R, Arrospide A. [Probabilistic Markov models in economic evaluation of health technologies: a practical guide]. Gac Sanit. 2010;24(3):209–214. Spanish. | ||

Rubio-Terrés C, Cobo E, Sacristán JA, Prieto L, del Llano J, Badia X; Grupo ECOMED. [Analysis of uncertainty in the economic assessment of health interventions]. Med Clin (Barc). 2004;122(17):668–674. Spanish. | ||

Marsh K, Xu, P, Orfanos P, Gordon J, Griebsch I. Model-based cost-effectiveness analyses for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a review of methods to model disease outcomes and estimate utility. PharmacoEconomics. 2014;32(10):981–993. | ||

Real Decreto-ley 16/2012, de 20 de abril, de medidas urgentes para garantizar la sostenibilidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud y mejorar la calidad y seguridad de sus prestaciones [Royal Decree-Law 16/2012, of 20 April, on urgent measures to ensure the sustainability of the National Health System and improve quality and safety of its services.]. BOE Nº 98, 24 de abril de 2012. Spanish. | ||

BotPlus 2.0. Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos [Bot Plus 2.0. General Council of Official Colleges of Pharmacists.]. Available from: https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/. Accessed March 16, 2016. Spanish. | ||

Beusterein KM, Davies J, Leach M, Meiklejohn D, Grinspan JL, O’Toole A, Bramham-Jones S. Population preference values for treatment outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a cross-sectional utility study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:50. | ||

Ferguson J, Tolley K, Gilmour L, Priaulx J. Health state preference study mapping the change over the course of the disease process in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Value Health. 2008;11(6):A485. | ||

Holzner B, Kemmler G, Sperner-Unterweger B, et al. Quality of life measurement in oncology – a matter of the assessment instrument? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(18):2349–2356. | ||

Greiner W, Weiinen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, et al. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4(3):222–231. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.