Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

Early father–daughter relationship and demographic determinants of spousal marital satisfaction

Authors Alsheikh Ali A, Daoud F

Received 14 September 2015

Accepted for publication 30 December 2015

Published 11 April 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 61—70

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S96345

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Ahmad Alsheikh Ali,1 Fawzi Shaker Daoud2

1Counseling Psychology Program, Faculty of Educational Sciences, Hashemite University, 2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman, Jordan

Abstract: This study examined several dimensions of early father–daughter relationship as predictors of marital satisfaction among 494 respondents. Descriptive comparative approach was used in result analysis. The Father Presence Questionnaire and Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire were used, in addition to a number of demographic variables. Results showed that only physical relationship with the father, and perceptions of father’s influence, had a positive significant impact on wives’ marital satisfaction. Of all domains, only positive feelings about the father had a negative impact on the husband's marital satisfaction. Most demographic variables had statistically significant effect on marital satisfaction. Sociocultural implications for marital satisfaction for wives and husbands are discussed.

Keywords: early father–daughter relationship, demographic, spousal marital satisfaction

Introduction

Parent–child relationships vary widely across cultures. Cultural differences exert a profound influence on human development because of culture’s influence on parental beliefs and attitudes regarding acceptable and unacceptable child behavior. Cross-cultural research clearly indicates that the society in which the mother and the father are brought up have an impact on their values. Arab and Eastern cultural perspectives, which have been described as sociocentric, interdependent, holistic, and collective, are in contrast to the individualistic Western culture, which stresses values such as self-control, self-reliance, individual achievement, and independence.1 In accordance with this view, Eastern cultures often reflect traditions that emphasize the group over the individual, cooperation over competition, and self-restraint over emotional expression. From an early age, children from both cultures are exposed to different ways of coping with social and interpersonal situations.

In terms of cultural identity, a vast majority of Arabs are authoritarian collectivists2 and adopt Islamic values in their familial, interpersonal, and social relationships. Despite exposure to Western culture and the influence of sociocultural changes, the basic traditional Islamic value system still prevails among this majority. It permeates almost all facets of their lives. Its profound effect is manifested in marriage arrangements, in sex roles and relationships, and in the hierarchal patterns of family relations. Values of sharing and sacrificing, especially those pertaining to women, play a central role in the socialization process.1 Furthermore, compliance and obedience to social norms and values become essential for family cohesiveness and connectedness. Thus, traditional Arab culture sets high, rigid expectations of a woman’s role as a wife and parent.

It seems that Jordanian Arabic culture in general puts high emphasis on the relationship between mother and daughter as the most important determinant of nurturing outcomes; the mother shapes the sex role of her daughter under the pressure of conservative social and religious expectations. One of the major concerns in nurturing girls in Jordanian Arab culture is to maintain a stereotype of beliefs and behaviors that secure later appropriate marriage. Daughters in such a culture are prepared to take full responsibility of raising kids as well as meeting household demands. Fathers in this context maintain an authoritarian role, which manifests itself in disciplinarian and decision-making tasks.

This study focuses on the influence of early father involvement in daughters’ future marital satisfaction. Such a study attempts to highlight three basic issues. First, the inclusion of daughters’ orientation toward their fathers through their perception of the affective, behavioral, and cognitive experiences with their fathers, which may reframe fathers’ traditional parenting practices. Second, ascertaining cross-generational familial influences in marital relationship and exploring the quality of early parent–child relations in shaping current marital behavior.3 Finally, such a study may contribute to the understanding of cultural influence on the sex role expectations and the way culture formulates certain codes of parenting and marital relationships.

Early father–daughter relationship, attachment, and marital satisfaction

Researchers have been focusing on the different consequences of fathers’ absence, not presence. Recently, however, efforts have been undertaken in the conceptualization of fathering through focusing on father involvement. Lamb et al4 have identified parental involvement by three basic components: one-to-one engagement with the child, accessibility and being physically present, and being responsible and continuing to adopt plans to fulfill the child’s needs and welfare. However, traditionally, most research focused on mother–child relationship. Role expectations of men and women are considered to be strictly distinct and divided into domains: while the father’s role is of a financial and disciplinarian authority, the mother’s role focuses on nurturing of and emotional involvement with the child. Although it is quite clear that future outcomes are affected by early attachment styles and parental involvement, little research has been conducted regarding the father’s involvement. Considering Jordanian Arab culture, despite the fact that many women have recently been engaged in the workforce, very little changes have occurred in fathers’ parenting role and their involvement with children. Cultural role expectations in the nurturing processes remain limited.

Developmentalists have focused on early parent–child relationships as an important determinant of later psychological adjustment. Specifically, children greatly benefit from a secure emotional attachment to someone: mother, father, other family member, or a substitute caregiver.5 The quality of the marital relationship affects children’s adjustment and development. Harmonious marriages tend to be associated with sensitive parenting and warm child–parent relationships. It may be concluded that when husbands and wives are satisfied with their marriage, the children tend to be more secure. However, when there is marital discord, children tend to be more anxious, aggressive, and insecure. Parents with poor marital quality are more likely to engage in problematic parenting styles, such as increased hostility and punitiveness, decreased warmth and reasoning, and increased inconsistency.6,7

Contemporary research regarding the dynamics of marital satisfaction and marital adjustment is immense and complex. It has repeatedly emphasized the role that early father–child relationship plays in the future adjustment of children.8–13 On the basis of accumulated research findings, some characteristics (acceptance–rejection) of early parent–child relationships are found to be crucial in determining children’s subsequent development. Particularly, certain dimensions (warm/nurturing–hostile) of early father–child relationship have been extensively studied due to their impact on future marital satisfaction.

Accordingly, despite cross-sectional and longitudinal studies pointing to the positive influence of father’s involvement and secure attachment experience on marital satisfaction; very little evidence has been found regarding the specific role of early father–daughter relationship in marital satisfaction in a conservative Arab culture.

Factors such as father’s presence, closeness, and communication of affection are found to be predictive variables of positive relationships.11,14–16 Research also shows that daughters’ self-appraisal, style of life, and self-perceptions represent distinct features of father–daughter relationships.17

Furthermore, research conducted on Arab culture stresses that factors such as authoritarian and permissive attitude, hostile and detached demeanor, and rejecting parenting have negative impact on children’s mental health. However, Dwairy18 asserts that whatever the parenting style in any given culture, inconsistency and incoherent parenting practices constitute the basis for the development of children’s psychological disorders. It is worth noticing here that research efforts in the context of Arab culture to examine the relationship between early father–daughter relationship and later psychological adjustment, especially marital satisfaction, has been lacking to a great extent.

Demographic variables

Three different demographic variables are considered important in the context of this study on Jordanian Arab culture. First, wives’ work status, which has increased over recent years, with accompanied limited changes in her sex role. Although wives have started to contribute to the enhancement of the family’s economic status, they are still expected to take the full responsibility of nurturing children in addition to other household duties. This development in her role may have an impact on marital satisfaction. Second, traditional versus nontraditional marriages constitute a very sensitive cultural issue. Most of the marriages in many Arab Muslim families are prearranged by the family and extended family, and such a phenomenon is considered a collective one. Moreover, marriage may be viewed as an institution that has a very clear and distinct role for both sexes. Culture does not encourage any kind of relationship before marriage, and it is very common that the first time that women and men know each other is after the engagement. Finally, having children in Arab/Muslim culture is considered to be the ultimate goal of marriage. Lack of children is one of the primary causes of divorce or multiple remarriages. In such a culture, it is justified to consider children an important determinant of marital satisfaction and therefore be included as a variable.

Aim of this study

On the basis of literature review, this study examines the influence of wives’ early relationship with their fathers on spousal marital satisfaction. A number of variables are investigated as possible determinants (Wives’ work status, Type of marriage [traditional versus nontraditional], and Existence of children). Only wives completed the “Father Presence Questionnaire”, while the “Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire” was completed by both husbands and wives.

Two hypotheses were tested: hypothesis 1: positive early father–daughter relationship factors will be related to greater levels of spousal marital satisfaction. Hypothesis 2: differences in marital satisfaction will be explained by Wives’ work status, Approach to marriage, and Existence of children.

Methods

Participants

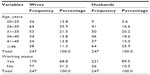

Married couples older than 18 years of age were considered the target population for this study. A total sample of 494 Jordanian respondents from Amman was used. The sample included 247 men and 247 women. Mean age of women was 32.12 years (standard deviation [SD] =5 years), while the mean age of men was 36.8 years (SD =5.98 years) (Table 1). All study participants provided a written informed consent form, which stressed the confidentiality of study data, their right to not participate, and was used to obtain their informed written consent. This study was approved by the research ethics committees of Hashemite University and Al-Ahliyya Amman University.

| Table 1 Participants according to age and work status |

Study instruments and procedures

Father Presence Questionnaire

The Father Presence Questionnaire, developed by Krampe and Newton,19 was used. It consists of 134 items distributed over ten subscales constituting the original version. For the purpose of this study, 71 items were chosen to cover six subscales: Feelings about the father, Mother’s support for relationship with father, Perception of father’s involvement, Physical relationship with father, Father–mother relationship, and Conceptions of father’s influence. Four-point Likert scale was used, with a total score ranging from 71 to 284, where a higher score indicates a more positive daughter–father relationship. The following subscales were used:

- Feelings about the father: asked to respond to statements such as “I looked up to my father” and “I felt inspired by my father”.

- Mother’s support for relationship with father: asked to respond to statements such as “My mother encouraged me to talk with my father” and “My mother respected my father’s judgment”.

- Perception of father’s involvement: asked to respond to statements such as “My father helped me with school work when I asked him” and “My father helped me learn new things”.

- Physical relationship with father: asked to respond to statements such as “My father hugged and/or kissed me” and “My father held me when I was a baby”.

- Father–mother relationship: asked to respond to statements such as “My father and mother supported and helped each other” and “My father and mother understood each other”.

- Conceptions of father’s influence: asked to respond to statements such as “Girls need their fathers” and “Fathers affect their sons’ and daughters’ relationships with their friends”.

Father Presence Questionnaire: validity and reliability

In the original version, different validity indicators showed a construct validity by using conformity factor analysis with a total eigenvalue of 77.8% and item factor loading values of ≥0.3. Convergent validity was also used. All coefficient values were ≥0.60.19

For adaptation purposes, this study relied on the findings by Al-Sheikh Ali,20 who conducted translation and back-translation of the Father Presence Questionnaire among a Jordanian sample of university students. In addition, judges’ evaluation was obtained to examine item appropriateness. Furthermore, internal validity was calculated among a pilot sample of 50 students. Results indicated that item–total correlation for all items ranged between 0.72 and 0.88, which reflects acceptable level of internal validity.

In terms of reliability, in the original version,19 a number of reliability indicators were shown. Among such indicators, Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability coefficients were found to be >0.89 for all subscales, which indicates a high level of reliability.

Such reliability results were supported by the findings of Al-Sheikh Ali,20 who used the same alpha equation among Jordanian university students. Results have indicated that the computed reliability coefficients for subscales ranged between 0.81 and 0.92, with a total reliability coefficient of 0.97, which suggests that the instrument, on the subscale as well as the total levels, reflects a high level of reliability.

Furthermore, this study was conducted using the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient method, with results ranging between 0.75 (for Father–mother relationship subscale) and 0.93 (for Perception of father’s involvement subscale). Overall coefficient value for the total score was 0.95 (Table 2).

| Table 2 Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values for the Father Presence Questionnaire and Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire |

Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire

On the basis of the definition of subdomains and the emotional component and cultural framework, 53 items were selected from various inventories and scales: Beier-Sternberg Discord Questionnaire,21 Conflict Resolution Scale,22 Conflict Tactics Scale,23 Construction of Problems Scale,24 and Sound Relationship House Questionnaire – Constructive versus Destructive Conflict Measures.25 Four-point Likert scale was used, with a total score ranging from 53 to 212, where the higher score indicates a more positive marital satisfaction.

Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire: validity and reliability

Upon translation to Arabic and back-translation to English, the item content appropriateness of the Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire was verified by eight faculty members and practitioners in the field of counseling and clinical psychology. Accordingly, expert suggestions were incorporated into the questionnaire taking into consideration language and culture.

The above procedure was a preliminary step toward the application of the questionnaire on a voluntary pilot sample of 15 pairs of husbands and wives, in order to examine item clarity, appropriateness, and internal validity. Results indicate that item–total correlation scores ranged between 0.70 and 0.86.

For marital satisfaction as well as the Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values were 0.93 respectively, which indicates appropriate levels of reliability (Table 2).

Demographic variables

Information on demographic variables through an established demographic questionnaire was collected. The variables studied were Wife’s work status (wives respond with “yes” or “no”), Approach to marriage (wives respond with “traditional” or “nontraditional”; a clarification was included to define approach to marriage as either “having any kind of relationship before engagement in nontraditional” or “the traditional, whereby they get to know each other for the first time after engagement”), and Existence of children (wives respond with “yes” in case of having ≥1children and “no” if they do not have children).

Procedure

In addition to the targeted respondents, other appropriate respondents identified and referred by the involved participants were included.

Snowball technique was used as the preferable mode of study because of the nature of the study, which requires the willingness of husbands and wives as couples to participate. Initial respondents themselves recommended other candidates for the study. Questionnaires were administered by trained college students who were already introduced to the nature of the study and trained on using the study tools. Familiar topics such as general orientation to research, characteristics of target population, basic interviewing skills, and data collection procedures were included in their training, in addition to the need for maintaining confidentiality of respondents.

Married men and women were contacted in their own settings and wherever they could be found. This included homes, offices, schools, universities, and other settings. After a brief unstructured interview to ascertain that participants are within the requirements for participation and to solicit their full participation, questionnaires were handed to them in an envelope. Although all necessary instructions were contained in the questionnaires, partners who agreed to participate were assured of anonymity and reminded to simply call on the research assistant to collect the questionnaires after completion. The administration of the questionnaires was to married couples, each in isolation from the other spouse, and linking codes were used for the set that went to a particular couple. For example, H7 and W7 (Husband 7 and Wife 7) were administered to a couple. This was to enable responses from couples to be matched for dyadic analytic purposes, as well as to eliminate any doubts about the codes or the erroneous impressions that the codes were linked to them personally. All incomplete questionnaires were excluded, as a procedure of elimination of any possible missing data, before statistical analysis. Furthermore, during the administration of the questionnaires, adequate information was given to participants and their informed consent was obtained. It was made clear to participants that they could withdraw from the study or skip any portions of the questionnaire that constituted discomfort to them in anyway. Furthermore, the return of the questionnaires was achieved in a sealed envelope, so data would remain completely anonymous.

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression analysis for the prediction of dependent variables (wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction) through examination of father–daughter presence factors was used. In addition, means, standard deviations, and nondirective analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine differences in marital satisfaction due to certain demographic variables. The descriptive comparative approach was used to compare between different groups based on study variables to identify the contribution value for each variable.

Findings

Hypothesis 1: positive early father–daughter relationship factors will be related to greater levels of spousal marital satisfaction.

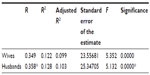

Multiple regression was used to assess Father Presence variables as predictors of wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction. For wives, the multiple R coefficient for father–daughter presence factors was 0.349, with F=5.352, degrees of freedom [df] =6.232, P≤0.01, which indicates a significant effect of the predicting variables on the dependent variables (wife’s marital satisfaction). The R2 value of 0.122 means that part of the variance of the wife’s marital satisfaction was explained by one or more of the father–daughter presence factors (Table 3).

| Table 3 Wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction as predicted by the Father Presence Questionnaire variables |

However, for husbands, the multiple R coefficients for father–daughter presence factors was 0.358, with F=5.132, df =6.232, P≤0.01, which indicates that there is a significant effect of the predicting variables on the dependent variables (husband’s marital satisfaction). The R2 value of 0.128 means that part of the variance of husband’s marital satisfaction was explained by one or more of the father–daughter presence factors (Table 3).

Furthermore, multicollinearity test was conducted for both wives’ and husbands’ variables. Results have shown for both that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all predicting variables were <5, which means that variance inflation value is within an acceptable range (Table 4).

| Table 4 Standardized beta coefficients of Father Presence Questionnaire predictors of wife and husband marital satisfaction |

Moreover, as a measure of the contribution of each variable to the model, the standardized beta coefficient was used for both wives and husbands. Results for wives indicate that only two predictors of father–daughter presence factors had significant impact on wives’ marital satisfaction: physical relationship with the father (β=0.24, t=2.43, P≤0.01); and perceptions of father’s influence (β=0.0175, t=2.55, P≤0.01). Both predicting factors had a positive impact on wives’ marital satisfaction.

In the case of the husbands, results show that four predictors of father–daughter presence factors had significant impact on their marital satisfaction: Feelings about the father (β=–0.368, t=–3.331, P≤0.01), Mother’s support for relationship with father (β=0.244, t=2.24, P≤0.01), Physical relationship with father (β=–0.263, t=2.55, P≤0.01), and Perceptions of father’s influence (β=0.167, t=2.332, P≤0.01). Only “Feelings about the father” factor had negative impact on husbands’ marital satisfaction, while the other three predicting factors had a positive impact on husbands’ marital satisfaction (Table 4).

Hypothesis 2: differences in marital satisfaction will be explained by Wives’ work status, Approach to marriage, and Existence of children.

Descriptive statistics

Regarding wives’ marital satisfaction, Table 5 shows that overall mean for wives was 107.80, with SD being 28.21 for working women, while the mean for nonworking wives was 118.12, with SD equaling 29.34. The mean for marital satisfaction as related to “Existence of children” variable was 113.15, with SD of 29.32, while the mean for women who have no children was 101.35, with SD being 25.04.Furthermore, the mean of marital satisfaction for traditionally married women was 113.47, with SD of 29.71, whereas it was 107.65, with SD equaling 27.61, for nontraditionally married women.

| Table 5 Mean values and standard deviations of wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction according to different demographic variables |

Husbands of working women, as shown in Table 5, scored less on marital satisfaction (mean: 114.076; SD: 17.73) compared to husbands of nonworking women (mean: 112.81; SD: 25.26). However, the mean of marital satisfaction for husbands who have children was 114.41, with SD of 18.48, as compared to the same for husbands who have no children (mean: 111.94; SD: 17.80). In the context of traditional versus nontraditional marriages, results show that the mean value of traditionally married husbands was 111.86 (SD: 14.64), while the mean of the nontraditionally married husbands was 116.48 (SD: 14.64).

Noninteractive ANOVA was conducted on the mean values of the demographic variables to test whether there are any significant differences among wives’ and husbands’ marital satisfaction levels (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 7 shows that the F-values for working wives, existence of children, and traditional marriage were 0.019, 1.60, and 4.70, respectively. Only the value for husbands who had traditional marriage was significant.

| Table 7 Noninteractive ANOVA for means of husbands’ marital satisfaction |

Discussion

This study examined early father–daughter relationship variables and the extent to which these variables can predict marital satisfaction among wives and husbands. In addition, this study investigated the influence of several demographic variables on marital satisfaction. Results have confirmed that “Physical relationship with the father” and “Perceptions of fathers’ influence” have significant positive effect on wives’ marital satisfaction. In other words, such early father–daughter interaction characteristics predict certain dimensions of wives’ marital satisfaction. These results support, to a great degree, research findings that point to the importance of early father–daughter relationship in the development of marital satisfaction. Such findings are implicitly consistent with the assertion by Seconda9 that the kind of relation that women have with their father determines the type of men they choose as their husbands and the kind of interaction they have with them. On the basis of this assumption, Seconda9 was able to differentiate types of fathers and daughters according to the nature of this relationship with the respective other. These findings also lend support to the results arrived at by Bowling and Wermer-Wilson,26 which emphasize the influence of a daughter’s relation with her father on her relation with other men and her mature sexual decisions later on. This may also contribute to the daughter’s psychosocial adjustment,10,16,27 social acceptance,28 sexual adjustment,14,16 perceived warmth and closeness,11,12,15 self-image,17 and self-esteem.29–31

In terms of husbands’ marital satisfaction, results have indicated that there are four predictors of father–daughter presence factors, which have a significant impact on husbands’ marital satisfaction: feelings about the father, mother’s support of daughter’s relation with the father, conceptions of father’s influence, and physical relationship with the father. Only feelings about the father had a negative impact on husband’s marital satisfaction, while the other three factors had a positive effect on husbands’ marital satisfaction. Feelings about the father, as an exception, can be viewed from a psychodynamic point of view. The wife’s expressed feelings toward the father may stir up feelings of jealousy and/or envy in the husband. This may explain the negative impact associated with the first predictor (Feelings about the father). For the other three predictors, results are consistent with the findings of Bowling and Wermer-Wilson26 and the early assertions by Bowlby32 that secured attachment in early childhood predicts future success and happiness in adulthood. It seems that husbands’ perceived marital satisfaction is affected, directly or indirectly, by the wife’s personality characteristics (ie, attachment pattern). Because marital relationship is an interactional one, any dysfunction in one partner can be assumed to eventually affect the other partner, affecting marital life including general satisfaction in marriage. From the wife’s perspective, one may assert that her psychological characteristics – which were partially formulated by her early relationship with the father – play a major role in facilitating or complicating the interaction process with the husband. Therefore, this lends support to findings by Perkins,17 which point to the important connection between wives’ style of life and self-appraisal, on the one hand, and previous relationship with the father on the other. Considering these findings, it seems that such characteristics may set a standard that enhances a positive and successful marital relationship.

In a cultural context, these results shed some light on the mother image in Arabic culture and the salient role that she plays in the formation of the daughter’s marital values. The mother who supports a close and intimate relationship between the daughter and her father may indirectly foster a positive and constructive relationship with the daughter’s future marriage partner. Her positive conception of her father’s influence also plays an important role in marital satisfaction and in projecting positive feelings on the marital relationship. The positive feelings she may experience with her father, as well as the security and warmth embedded in it, will most probably facilitate a more supportive and rewarding relationship with her husband.

According to this investigation, several demographic variables were found to be statistically significant in predicting wives’ marital satisfaction. Results indicated that working wives have more marital satisfaction than nonworking ones. This study, therefore, confirms results of some early studies that marital quality is higher among wives who are employed than among housewives.33,34 In the context of the Enhancement hypothesis, Kessler and McRae35 assume that the self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social support that women acquire in relation to their role diversity represent a positive force in their lives and lead to life satisfaction. This is supported by the findings of Breik and Daoud,36 who found significant differences between working and nonworking women in overall psychological adjustment. The percentages of nonworking women who suffer from stress and somatic complaints were significantly higher than in their working women counterparts.

Contrary to the findings of Cherlin,37 Janssen et al,38 and Kalmijn,39 who had shown that highly educated women had a higher rate of unstable marriages, implicitly, one can assume from the findings of this study that working women, in most cases, have higher levels of education, which is considered to be of high esteem in contemporary Arab society and viewed by both sexes as an essential condition for social and economic advancement. In general, women’s education and employment has acquired, in recent years, a great deal of importance and value both socially and economically.

Husbands showed no significant differences in their marital satisfaction relevant to wives’ work status. This may be attributed to the general male attitude prevalent in Arab society, which considers women’s work as a secondary addition, not an essential one. Furthermore, there are no changes in her cultural role as a wife and as a woman in society.

In terms of “Existence of children”, no significant differences were found in both husbands’ and wives’ marital satisfaction. In accordance with a long line of research findings that support the notion of a general decline in marital satisfaction as a consequence of having children,40–43 wherein overall absence of children had a significant positive effect on marital happiness, this study partially and indirectly agrees with such results. Despite the traditional cultural emphasis on children in Arab society and its symbolic meaning for both women’s and men’s identity and role legitimacy, however, one can assume that contemporary Western values have spread into Arab and Muslim society. New generations are more inclined to be preoccupied with improving the quality of life and economic well-being over reproduction. Such results may point to a transformation in Arab and Muslim society toward being an open society.

Finally, traditional marriage has contributed to marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives. The deeply rooted formal value system of Arab and Muslim culture prohibits establishing any emotional relationships prior to marriage. Going against such cultural mandate could potentially cause unnecessary tension for young men and women within the context of the hierarchical family system. Marital decisions in such a cultural setting become a collective one. In the context of such social and familial climate, it is only logical to expect that regardless of type of marriage, overall societal expectations take over any individual considerations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has advanced our understanding of marital satisfaction in relation to the quality of early father–daughter interaction, as well as in relation to a number of demographic variables. The primary relationship between a daughter and her father plays a significant role in both her marital satisfaction as well as her husband’s marital satisfaction. This is consistent with the contributions of many theorists and researchers. If the daughter had experienced a safe and secure relationship with her father, she most probably will carry those feelings to her relation with the husband.

“Traditional marriage” and “Existence of children” variables were found to have significant influence on wives’ marital satisfaction, while only traditional marriage was of significance in husbands’ marital satisfaction. Despite exposure to Western culture, the influence of traditional Arab culture remains strong.

However, cultural transformation in Arab society recognizes the significance of parents’ role in the socialization process. As a result, it is quite appropriate to expect a change in the role of the father, who is being viewed increasingly as a significant factor in the child’s psychosocial development. Therefore, it can be concluded that despite the strong influence of traditional societal values, sex role changes have influenced contemporary Arab society. Clearly, one can say with a great deal of confidence that the early relationship with the mother is not any more the sole factor determining children’s personality development.

Our study may have important implications for therapists and health professionals. These findings may assist them in understanding and assessing their clients. They could use such information in counseling those marriage partners who seek stability in marital relationship, as well as those who are threatened by separation or divorce.

Limitations

The study sample consisted of participants with a broad age range, which may present different age-related dynamics. Although the instructions related to the study were clear and specific, it is possible responses may have been given without considering the importance of independent and private completion of questionnaires.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Dwairy M. Cross-Cultural Counseling: The Arab-Palestinian Case. New York, NY: Haworth; 1998. | |

Al-Sabaie A. Psychiatry in Saudi Arabia: cultural perspectives. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1989;26:245–262. | |

Whitbeck L, Hoyt DR, Huck SM. Early family relationships, intergenerational solidarity, and support provided to parents by their adult children. J Gerontol. 1994;49:S85–S94. | |

Lamb ME, Pleck JH, Levine JA. Effects of increased paternal involvement on fathers and mothers. In: Lewis C, O’Brien M, editors. Reassessing fatherhood: New observations on fathers and the modern family. London: Sage Publications Inc.; 1987:109–125. | |

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1: Attachment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1982. [new printing, 1999, with a foreword by Allan N. Schore; originally published in 1969]. | |

Floyd FJ, Zmich DE. Marriage and the parenting partnership: perceptions and interactions of parents with mentally retarded and typically developing children. Child Dev. 1991;62(6):1434–1448. | |

Gable S, Belsky J, Crinic K. Marriage, parenting, and child development: Progress and prospects. Journal of Family Psychology. 1992;5(3–4):276–294. | |

Pruett K. The Nurturing Father. New York, NY: Warner Books; 1987. | |

Seconda V. Women and Their Fathers. New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell; 1992. | |

Biller HB, Kimpton JL. The father and the school-aged child. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1997:143–161. | |

Floyd K, Morman MT. Affection received from fathers as a predictor of men’s affection with their own sons: tests of the modeling and compensation hypothesis. Commun Monogr. 2000;67:347–361. | |

Flouri E, Buchanan A. What predicts good relationships with parents in adolescence and partners in adult life? Findings from the 1958 British birth cohort. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(2):186–198. | |

Morman MT, Floyd K. A “changing culture of fatherhood”: effects on affectionate communication, closeness, and satisfaction in men’s relationships with their fathers and their sons. West J Commun. 2002;66:395–411. | |

Lamb ME. Fathers in child development: an introductory overview and guide. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1997:1–18. | |

Coiro MJ, Emery RE. Do marriage problems affect fathering more than mothering? A quantitative and qualitative review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998;1(1):23–40. | |

Lamb ME, Lewis C. The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2004:272–306. | |

Perkins R. The father-daughter relationship: familial interactions that impact a daughter’s style of life. Coll Stud J. 2001;35:616–627. | |

Dwairy M. Parental acceptance-rejection: a fourth cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19:30–35. | |

Krampe EM, Newton RR. The Father Presence Questionnaire: A New Measure of the Subjective Experience of Being Fathered. Huntingdon Valley, PA: Men’s Studies Press, Gale Group, Thomson Corporation Company; 2006. | |

Al-Sheikh Ali A. Father – daughter relationship during childhood, and its relation to mental health during adulthood. Damascus University Journal For Educational and Psychological Sciences. In press 2011. | |

Beier EG, Sternberg DP. Beier-sternberg discord questionnaire (DQ). In: Corcoran K, Fischer J, editors. Measures for Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook (2000). Vol. 1. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1977;27(3):92–97. | |

Olson DH, Fournier DG, Druckman JM. Enriching and nurturing relationship issues, communication and happiness- conflict resolution scale. In: Tzeng OCS, editor. Measurement of Love and Intimate Relations (1993). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc; 1985;43–50. | |

Straus. Conflict tactics scale (CTS). In: Tzeng OCS, editor. Measurement of Love and Intimate Relations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc; 1979. | |

Heatherington EM. Construction of problems scale (CPS+). In: Corcoran K, Fischer J, editors. Measures for Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook (2000). Vol. 1. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1998. | |

Gottman JM. Gottman sound relationship house questionnaires- constructive versus destructive conflict measures. In: Gottman J, editor. The Marriage Clinic: A scientifically-based marital therapy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1999. | |

Bowling SW, Wermer-Wilson R. Father-daughter relationships and adolescent female sexuality. J HIV AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2000;4:5–28. | |

Amato PR. More than money? Men’s contributions to their children’s lives. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Men in Families: When do They Get Involved: What Difference Does It Make? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998:241–278. | |

Snarey J. How Fathers Care for the Next Generation: A Four-Decade Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. | |

Mori M. The influence of father-daughter relationship and girls’ sex-roles on girls’ self-esteem. Arch Womens Ment Health. 1999;2(1):45–48. | |

Pleck JH, Masciadrelli BP. Paternal involvement by U. S. residential fathers: levels, sources, and consequences. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2004:222–271. | |

Cooper SM. Associations between father-daughter relationship quality and the academic engagement of African American adolescent girls: self-esteem as a mediator? J Black Psychol. 2009;35:495–516. | |

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1: Attachment. The International Psycho-Analytical Library. Vol. 79. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis; 1969:1–401. | |

Houseknecht SK, Macke AS. Combining marriage and career: the marital adjustment of professional women. J Marriage Fam. 1981;43(3):651–661. | |

Simpson IH, England P. Conjugal work roles and marital solidarity. In: Aldous J, editor. Two Paychecks. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982:147–171. | |

Kessler RC, McRae JA. The effect of wives’ employment on the mental health of married men and women. Am Sociol Rev. 1982;47:216–227. | |

Breik DW, Daoud SF. Effect of participation in the workplace on the physical and psychological well – being of working women, a comparative study on working and nonworking women in Amman, Jordan. J Soc Sci. 2009;37(3):115–154. | |

Cherlin A. Work life and marital dissolution. In: Levinger G, Moles OC, editors. Divorce and Separation: Context, Causes, and Consequences. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1979;151–166. | |

Janssen J, Poortman A, De Graaf PM, Kalmijn M. The instability of marital and cohabiting relationships in the Netherlands. Mens en Maatsschappij. 1998;73:4–26. | |

Kalmijn M. Father involvement in childrearing and the perceived stability of marriage. J Marr Fam. 1999;61:409–421. | |

White L, Edwards JN. Emptying the nest and parental well-being: an analysis of national panel data. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55:235–242. | |

Belsky J, Kelly J. The Transition to Parenthood: How the First Child Changes a Marriage. Why Some Couples Grow Closer and Others Apart. New York, NY: Dell; 1994. | |

Cox MJ, Paley B, Burchinal M, Payne CC. Marital perceptions and interactions across the transition to parenthood. J Marriage Fam. 1999;61:611–625. | |

Shapiro AF, Gottman JM, Carrere S. The baby and the marriage: identifying factors against decline in marital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14(1):59–70. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.