Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 17

Different Perspectives of Spanish Patients and Professionals on How a Dialysis Unit Should Be Designed

Authors Arenas Jiménez MD, Manso P, Dapena F, Hernán D, Portillo J, Pereira C, Gallego D, Julián Mauro JC, Arellano Armisen M, Tombas A, Martin-Crespo Garcia I, Gonzalez-Parra E, Sanz C

Received 5 August 2023

Accepted for publication 12 October 2023

Published 1 November 2023 Volume 2023:17 Pages 2707—2717

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S434081

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Maria Dolores Arenas Jiménez,1 Paula Manso,1 Fabiola Dapena,1 David Hernán,1 Jesús Portillo,1 Concepción Pereira,1 Daniel Gallego,2 Juan Carlos Julián Mauro,2 Manuel Arellano Armisen,2,3 Antonio Tombas,4 Iluminada Martin-Crespo Garcia,5 Emilio Gonzalez-Parra,6 Cristina Sanz1

1Renal Foundation, Madrid, Spain; 2National Federation of Associations for the Fight Against Kidney Diseases (ALCER), Madrid, Spain; 3Platform of Patient Organizations (POP), Zaragoza, Spain; 4Association of Renal Patients of Catalonia (ADER), Barcelona, Spain; 5Madrid Association for the Fight Against Kidney Diseases, Madrid, Spain; 6Hospital Foundation Jiménez Diaz, Madrid, Spain

Correspondence: Maria Dolores Arenas Jiménez, Fundación renal Calle Jose Abascal, 42, 1 º izda, Madrid, 28003, Spain, Tel +34-673429833, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Aim: The opinion of hemodialysis patients, professionals and family members is rarely considered in the design of a hemodialysis unit.

Purpose: To know and compare the opinion and preferences of patients, family members and professionals regarding the design of a dialysis unit and the potential activities they believe should be carried out during the session in order to provide architects with real information for the construction of a dialysis center.

Patients and Methods: Anonymous and voluntary survey in electronic format addressed to patients, relatives and professionals belonging to the 18 hemodialysis centers of the renal foundation and to ALCER and its different delegations, in relation to leisure activities to be carried out in the dialysis center and preferred design of the treatment room. The results obtained between the patient-family group and the professionals were compared.

Results: We received 331 responses, of which 215 were from patients and family members (65%) and 116 (35%) from professionals. The most represented category among professionals was nursing (53%), followed by assistants (24%) and physicians (12.9%). A higher proportion of patients (66%) preferred rooms in groups of 10– 12 patients as opposed to professionals who preferred open-plan rooms (p< 0.001). The options that showed the most differences between patients and professionals were chatting with colleagues and intimacy (options most voted by patients/families), versus performing group activities and visibility (professionals).

Conclusion: The professionals’ view of patients’ needs does not always coincide with the patients’ perception. The inclusion of the perspective of people with kidney disease continues to be a pending issue in which we must improve both patient organizations and professionals, and the opinion of professionals and patients must be included in the design of a dialysis unit and the activities to be developed in it.

Plain Language Summary: People with kidney disease on hemodialysis spend 4 hours of their lives three times a week in hemodialysis units. Although the new concept of 21st century medicine gives special prominence to the opinion of patients and family members, the reality is that this is rarely considered when establishing the requirements that a dialysis center should meet.

The aim of this study is to know and compare the opinion and preferences of patients, family members and professionals regarding the design of a dialysis unit and the potential activities they believe should be carried out during the session in order to provide architects with real information for the construction of a dialysis center.

This is the first survey in Spain that attempts to approach both the opinions of the patients and the professionals working in the units.

The professionals’ view of patients’ needs does not always coincide with the patients’ perception. The inclusion of the perspective of people with kidney disease continues to be a pending issue in which should be improve both patient organizations and professionals, and the opinion of professionals and patients should be included in the design of a dialysis unit and the activities to be developed in it.

Keywords: hemodialysis, patient experience, dialysis unit design, preferences, patients, healthcare professionals

Introduction

Two thousand five hundred years ago Lao-Tse said: “Architecture is not four walls and a roof; it is the arrangement of spaces and the spirit generated within”. The architectural design of patient care spaces has an enormous importance in aspects that are fundamental for the proper performance of the activity,1 but they have to consider also the soul of the activity that takes place in it. Hemodialysis units must be designed with the aim of achieving the greatest possible mental, physical and social rehabilitation.

Historically, the definition of what a hospital and outpatient hemodialysis unit should be like has been based on the recommendations of scientific societies and health authorities2–4, as well as on the requirements of the different state and regional regulations.5 This definition contemplates, among other things, the rooms it should contain, their square meters and accessibility.6–13 In addition, aspects such as worker and patient safety14–16 and respect for the environment and sustainability17,18 are also considered.

Although the new concept of 21st century medicine gives special importance to the opinion of patients and family members,19 the reality is that this is rarely considered when establishing the requirements that a dialysis center must meet. People with kidney disease on hemodialysis spend 4 hours of their lives three times a week in hemodialysis units. It seems important to know their opinion about how the hemodialysis center should be designed.

A recent systematic review20 shows that factors such as location, internal environment, equipment, technology, and furniture (chairs, beds, coaches, etc.) influence patient satisfaction and experience during the hemodialysis treatment.

The aim of this study is to know and compare the opinion and preferences of patients, family members and professionals regarding the design of a dialysis unit and the potential activities they believe should be carried out during the session in order to provide architects with real information for the construction of a hemodialysis center.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Comparison of the results of the same questionnaire administered between June 15, 2023 and June 30, 2023 to two independent samples of the population in Spain: people with kidney disease and family members versus professionals working in the field of hemodialysis. The questionnaire asks about aspects of the design of the hemodialysis unit and activities to be developed during the hemodialysis session.

Survey Administration Methodology

The survey was sent by e-mail and was addressed to relatives and patients with kidney disease affiliated to the National Federation of Associations for the Fight against Kidney Disease (ALCER) and its different delegations, as well as to patients and professionals belonging to the 17 hemodialysis centers of the Renal Foundation in Spain who wished to participate. The survey was anonymous and voluntary.

Content of the Survey

The questionnaire consisted of multiple-choice and open-ended questions, which evaluated different aspects of the unit in general and some facilities such as the waiting room, dialysis room, dressing rooms, dialysis station, among others; as well as entertainment options during the session. The contents of this survey were suggested by a sample of renal patients belonging to the association of renal patients and health professionals who validated the relevance of the questions and are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Questions Asked and Possible Answers |

Variables

In addition to the specific questionnaire, some minimum demographic variables were collected: age, sex, person completing the survey: patient, family member or professional, and different professional categories: physician, nurse, nursing assistant, member of the renal patient support group (nutritionists, social workers, psychologists, sports technicians).

Statistical Analysis

Numerical variables were described with the mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were described with the number and percentage of subjects. Comparisons between groups were performed with Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. In all tests, the significance level was considered to be p<0.05. All the analyses were performed using the SPSS 28 statistical program for Windows.

The analysis of qualitative data aims to obtain conclusions about subjective and relative realities. In this study, a categorization and systematization of the responses to open ended question is established for subsequent analysis in each category.

Ethical Considerations

The current study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz (act n° 01/23) (PIC010-23_FJD_FRIAT) and complied with the standards recognized by the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, as well as the Standards of Good Clinical Practice, in addition to compliance with Spanish legislation on biomedical research (Law 14/2007). Before answering the survey, participants were given access to the following information sheet. Answering the survey and sending it was considered as the participant’s acceptance to participate in the study. No personal data were collected and there was no possibility of knowing the identity of the participants.

Results

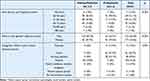

A total of 331 answers were received, of which 215 were from patients and family members (65%) and 116 (35%) from professionals. The Table 2 shows the description of patients and professionals. The two populations were demographically different: older patients and predominantly male (60%) and younger professionals with almost 80% women. The most represented category among professionals was nursing (53%), followed by assistants (24%) and physicians (12.9%).

|

Table 2 Characteristics of the Study Populations |

Comparison Between Patients and Professionals

The Table 3 shows the comparison between preferences of patients/ relatives and professionals in relation to how the hemodialysis room should be designed and what activities should be carried out during the dialysis session. Two thirds of the patients preferred small rooms with 10–12 places, while only one third of the professionals opted for this alternative (p<0.001). The options that showed the greatest differences between patients and professionals were related to the functionality to which the design of the hemodialysis room was directed: choice of chatting with colleagues and need for intimacy (options most voted by patients/families), as opposed to the choice of carried out the group activities and visibility from nursing control (professionals).

|

Table 3 Preferences of Patients and Professionals in the Design of the Hemodialysis Room and Activities to Be Carried Out During Dialysis |

In Table 4 a compilation of the main responses to the questions asked, ordered from most to least frequent responses are showed.

|

Table 4 Compilation of the Main Responses to the Questions Asked, Ordered from Most to Least Frequent Responses |

Influence of Age or Gender in Patients

Age over 65, but not gender, influenced some of the activities chosen by patients. Watching movies and documentaries and talking to other colleagues during the hemodialysis session was chosen in higher proportion by patients over 65 years than by those under 65 years of age (76% vs 57.8%; p<0.05 and 26.5% vs 13.3% respectively; p<0.05). Patients under 65 years were more open to the use of new technologies such as virtual reality (14% vs 2.2%; p=0.016).

Discussion

The most important result of this study is the fact that the opinions and preferences about how should be a hemodialysis unit is not the same for patients and health professionals. As an example, other studies also show that there is no congruence of perceptions between patients and nurses about aspect like caring behaviors,21 exercice22 or nutrition.23

People with kidney disease on hemodialysis spend more than four hours of their lives three times a week in the hemodialysis units. Regardless of the basic requirements of quality of care, safety and comfort that every hemodialysis unit must meet, this study considers it important to go further in order to improve the experience of the application during those 4 hours. As an example, the Spanish center guidelines that establish how the architectural design of hemodialysis units should be in Spain4 do not reflect the opinions and preferences of people with kidney disease on dialysis about what the ideal dialysis center should be like. People with kidney disease are the focus of hemodialysis units24,25 and these units should be designed to improve their experience26,27 so their opinions should be considered when giving indications on how to design them.

The health professionals who work in the hemodialysis units are another important part that must be attended to in this design, especially the nursing staff.

This is the first survey in Spain that attempts to approach both the opinions of the patients and the professionals working in the hemodialysis units.

Many of the answers obtained in the survey coincide with the recommendations made in the Spanish guidelines for hemodialysis centers4, such as the need for the center to provide comfort, privacy, spaciousness, natural light, ventilation, and for a domestic environment to predominate over a hospital environment, as evidenced by the phrase “a center that looks less like a hospital”, which increases the validity of these guidelines.4

One of the novelties of this survey is that it gives a voice to the people who dialyze and work in dialysis units in more specific aspects of structure and operation such as the layout of the dialysis room, the color of the walls, the presence of natural plants, the location of the nursing control in relation to the dialysis station, the entertainment options during the session, types of lighting and elements that they consider necessary to be in their dialysis station such as sockets, table, bag hanger, etc. and attempts to translate into practice the broad and ill-defined terms we commonly use, such as comfort or privacy.

Although aspects such as air conditioning, natural light and a quiet environment with absence of noise28 were equally valued by patients and professionals, there are other characteristics in which the opinions and/or preferences of professionals do not coincide with those of people with kidney disease, such as the layout of the dialysis room or the activities to be performed during the session.

Most patients prefer smaller rooms or rooms distributed in groups of 10–12 patients, which allow them a better relationship with their colleagues and greater intimacy, while a greater number of professionals prefer large, diaphanous rooms. Probably all opinions, although different, should be considered when designing a center with smaller patient modules, but respecting the necessary amplitude required by the professionals. In general, patients attach greater importance to comfort, the relationship in the room with other colleagues and intimacy, while professionals prioritize patient control and safety.

The different responses found in professionals and patients further support, if possible, the need to include the latter, as well as their relatives and caregivers, in many processes that we take for granted and to listen to their views and preferences to achieve the goal improving the patient experience.

Early involvement of physicians and nurses in the construction of health care facilities29,30 is not new, and has been shown to reduce initial and operating costs, improve facility performance, and provide a safe environment with the best solutions.29,30 This survey allowed the architects to modify the initial design of the unit and adapt it to the preferences of patients and professionals. In this study, the single, open-plan room initially proposed was converted into separate 12-place rooms with movable panels. Interior gardens were placed to allow the inclusion of plants as a decorative element and the white lights were changed to warm ones.

Especially relevant is the fact that, although the questions are directed to the interior design of the dialysis center in architectural terms, both professionals and patients, when asked open-ended questions: “What would you highlight as the best thing about the dialysis center you know? What would your ideal center be like?”, mention the human quality, the care provided by professionals, and the work team and work environment, as well as highlighting aspects that have nothing to do with the architecture itself, such as waiting times, staff training and ratios patient/professional. This analysis, like other studies,31,32 highlights the need to humanize not only the treatment but also the infrastructures, since its are vehicles for humanizing care. Designing spaces where patients feel comfortable while receiving their treatment it is a more important question than it may seem at first glance. Unlike other pathologies, people on hemodialysis not only value personal relationships with healthcare personnel as determinants of their satisfaction. Due to the frequent visits (3 or more times a week) of dialysis patients they also prioritize other aspects like facility, therapy.20,33 Another study, like this, showed that HD patients emphasized more comfortable chairs at the dialysis facility would improve their treatment experience, in addition to having better cable television channels for better entertainment.20,34

On the other hand, this survey also shows the importance of new technologies (Tablet, Wifi, security, computers, data transfer, etc.) in improving the experience of both patients and workers, which we must necessarily incorporate in the design of new units and adapt existing ones. This study has limitations. First, the sample may not be representative of the entire dialysis population, since it is likely that people who do not have access to e-mail are not represented, but at least they are in the population that answered the survey.Second, the tool used is a newly created survey not validated designed with and for patients and professionals that only aims to explore the opinions of both groups about some issues related to the design and activities carried out in hemodialysis units, however, we consider it a strength that both, the patient and professionals, have participated in its preparation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no congruence of preferences between patients and staff as regards to how a HD center must to be and about the activities to carry out in a hemodialysis center. Patients prefer smaller room, privacy and chatting with colleagues and professionals prefer open room, visibility and group activities. Further research is needed to understand the impact of these new units on the patient and professional experience.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and patients of the centers where the study was performed for their invaluable contribution in this study. We thank ALCER for the diffusion of questionnaires.

Disclosure

Mr Juan Carlos Julián Mauro reports that in the last 3 years, his employer has received financial aid from the following companies related to the treatment of people with kidney conditions: Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Baxter, CSL Vifor, Diaverum Services, Fresenius Medical Care, GSK, Hansa Biopharma and Novartis. These aids were in no case intended for this research. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Remón Rodríguez C, Quirós Ganga PL, González-Outón J, et al. Equipo multidisciplinario para la organización y gestión del hospital de día médico de nefrología. recovering activity and illusion: the nephrology day care unit. Nefrologia. 2011;31(5):545–559. doi:10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.Jul.11006

2. Guía de Programación y Diseño – unidades de Hemodiálisis: ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo- Dirección General de Planificación Sanitaria:Madrid, abril [Programming and Design Guide – Hemodialysis Units: Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs- General Directorate of Health Planning: Nefrologia]; 1986. (consultado 21/10/2022).

3. Solozábal C, Pérez García R, Martí A, et al. Sociedad Española de Nefrología. Características estructurales de las unidades de hemodiálisis. Guías de centros de hemodiálisis [Structural features of hemodialysis unit. Hemodialysis centers guides]. Nefrología. 2006;26(Suppl 8):5–10.

4. Alcalde-Bezholda G, Alcázar-Arroyo R, Angoso-de-guzmán M, et al. Guía de unidades de hemodiálisis 2020. Nefrologia. 2021;41(supl 1):1–77.

5. de Depuración Extrarrenal U. Estándares y recomendaciones de calidad y seguridad informes, estudios e investigación 2011 ministerio de sanidad, política social e igualdad [Extrarenal Purification Unit. QUALITY AND SAFETY STANDARDS AND RECOMMENDATIONS. REPORTS, STUDIES AND RESEARCH 2011 MINISTRY OF HEALTH, SOCIAL POLICY AND EQUALITY]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/docs/EERR/UDE.pdf.

6. McDonald HP, Hessert RT, Thomson GE, et al. Design, equipment, and function of a fifteen bed hemodialysis unit. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1966;12:370–375.

7. Haas M. Building a dialysis facility within the confines of a skilled nursing facility. Nephrol News Issues. 1999;13(7):42–43.

8. Previdi WA. Dialysis unit design: it’s in the details. Part II. Nephrol News Issues. 1994;8(4):30–31.

9. Previdi WA. Facility design. Part I. Dialysis unit design: it’s in the details. Nephrol News Issues. 1994;8(3):31–34.

10. Kopstein J, Prompt CA. Uma unidade de hemodiálise de estrutura modular [A modular structured hemodialysis unit]. AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1975;21(6):189–192.

11. Coggins WJ. The hospital ambulant unit--report of an experience. N Engl J Med. 1965;272(16):837–842. doi:10.1056/NEJM196504222721606

12. Haas M. Avoiding the pitfalls when building a new dialysis facility. Nephrol News Issues. 1998;12(8):55, 56, 58.

13. Evans DB, Dewardener HE, Curtis JR, et al. prototype maintenance haemodialysis unit. Lancet. 1965;1(7393):1012–1013. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(65)91232-8

14. Ulrich BT, Kear TM. The health and safety of nephrology nurses and the environments in which they work: important for nurses, patients, and organizations. Nephrol Nurs J. 2018;45(2):117–168.

15. Gardner TW. Incorporating safety concerns into design and construction. Provider. 1990;16(8):11–12.

16. Heung M, Adamowski T, Segal JH, et al. A successful approach to fall prevention in an outpatient hemodialysis center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1775–1779. doi:10.2215/CJN.01610210

17. Barraclough KA, Gleeson A, Holt SG, et al. Green dialysis survey: establishing a baseline for environmental sustainability across dialysis facilities in Victoria, Australia. Nephrology. 2019;24(1):88–93. doi:10.1111/nep.13191

18. Connor A, Mortimer F. The green nephrology survey of sustainability in renal units in England, Scotland and Wales. J Ren Care. 2010;36(3):153–160. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6686.2010.00183.x

19. Prieto-Velasco M, Quiros P, Remon C, Burdmann EA; Spanish Group for the Implementation of a Shared Decision Making Process for RRT Choice with Patient Decision Aid Tools. The concordance between patients’ renal replacement therapy choice and definitive modality: is it a Utopia? PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0138811. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138811

20. Al Nuairi A, Bermamet H, Abdulla H, Simsekler MCE, Anwar S, Lentine KL. Identifying patient satisfaction determinants in hemodialysis settings: a systematic review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;15:1843–1857. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S372094

21. Alikari V, Gerogianni G, Fradelos EC, Kelesi M, Kaba E, Zyga S. Perceptions of caring behaviors among patients and nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):396. doi:10.3390/ijerph20010396

22. Thompson S, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Molzahn A. A qualitative study to explore patient and staff perceptions of intradialytic exercise. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(6):1024–1033. doi:10.2215/CJN.11981115

23. Sladdin I, Ball L, Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W. A comparison of patients’ and dietitians’ perceptions of patient-centred care: a cross-sectional survey. Health Expect. 2019;22(3):457–464. doi:10.1111/hex.12868

24. Tong A, Winkelmayer WC, Wheeler DC, et al. SONG-HD Initiative. Nephrologists’ perspectives on defining and applying patient-centered outcomes in hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(3):454–466. doi:10.2215/CJN.08370816

25. Lin CC, Hwang SJ. Patient-centered self-management in patients with chronic kidney disease: challenges and implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):9443. doi:10.3390/ijerph17249443

26. Dad T, Grobert ME, Richardson MM. Using patient experience survey data to improve in-center hemodialysis care: a practical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(3):407–416. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.12.013

27. Wood R, Paoli CJ, Hays RD, et al. Evaluation of the consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems in-center hemodialysis survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(6):1099–1108. doi:10.2215/CJN.10121013

28. James R. Noise and acoustics in renal units and hospitals [corrected]. J Ren Care. 2008;34(1):33–37. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6686.2008.00008.x

29. Keys Y, Silverman SR, Evans J. Identification of tools and techniques to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration during design and construction projects. HERD. 2017;10(5):28–38. doi:10.1177/1937586716684135

30. Alves TD, Lichtig W, Rybkowski ZK. Implementing target value design. HERD. 2017;10(3):18–29. doi:10.1177/1937586717690865

31. Casaux-Huertas A, Cabrejos-Castillo JE, Pascual-Aragonés N, et al. Impacto de la aplicación de medidas de humanización en unidades de hemodiálisis [Impact of the application of humanization measures in hemodialysis units]. Enferm Nefrol. 2021;24(3):279–293. doi:10.37551/S2254-28842021025

32. Sousa KHJF, Damasceno CKCS, Almeida CAPL, et al. Humanization in urgent and emergency services: contributions to nursing care. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2019;40:e20180263. Portuguese, English. PMID: 31188988. doi:10.1590/1983-1447.2019.20180263

33. Gu X, Itoh K. Factors behind dialysis patient satisfaction: exploring their effects on overall satisfaction. Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19(2):162–170. doi:10.1111/1744-9987.12246

34. Chenitz KB, Fernando M, Shea JA. In-center hemodialysis attendance: patient perceptions of risks, barriers, and recommendations. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(2):364–373. doi:10.1111/hdi.12139

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.