Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 14

Design and Initial Validation of a Humanistic Care Evaluation Tool

Authors Wang X, Hu Y, Tao J, Hu F, Li P, Shao D, Pan HF , Xu T

Received 23 March 2021

Accepted for publication 19 August 2021

Published 25 August 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2307—2313

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S309104

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Xiaohu Wang,1,* Yuqian Hu,2,* Jie Tao,3 Fuyong Hu,4 Peng Li,1 Donghua Shao,5 Hai-Feng Pan,2 Tao Xu6

1The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, People’s Republic of China; 3Anhui Provincial Hospital, Hefei, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Public Health, Bengbu Medical College, Bengbu, People’s Republic of China; 5Public Anhui Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission, Hefei, People’s Republic of China; 6School of Pharmacy, Anhui Key Laboratory of Bioactivity of Natural Products, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Hai-Feng Pan

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, 230032, People’s Republic of China

Tel/Fax +86 551 65161165

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Tao Xu

School of Pharmacy, Anhui Key Laboratory of Bioactivity of Natural Products, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, People’s Republic of China

Email [email protected]

Objective: This study aimed at developing and validating a humanistic care tool in Anhui province that could be used across Chinese public hospitals, and to reflect the humanistic care from patients’ perspective.

Participants: A cross-sectional survey was conducted in three public hospitals of Anhui Province, China by adopting simple random sampling, which included 312 outpatients and 323 inpatients.

Methods: The dimensions of the tool were set according to “Further Improve Medical Service Action Plan” in China and Patient-Doctor Relationship Questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated and used to evaluate the reliability of this tool. Construct validity was tested by the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The associations between characteristics and humanistic care were analyzed by binary logistic regression.

Results: These initial findings showed that about two-thirds of the respondents experienced humanistic care. Both the reliability and construct validity of the humanistic care evaluation tool were suitable Social aspects (location and yearly income), treatment style and having a regular doctor were significantly associated with better humanistic care (all P< 0.05).

Conclusion: The humanistic care tool can directly reflect the humanistic care from patients’ perspective, and can be popularized and applied across Chinese public hospitals. These findings have important implications to further improve medical service in Chinese public hospitals.

Keywords: humanistic care, hospital, evaluation tool

Introduction

Since medical care has switched from the biomedical to the biopsychosocial medical model, treatment has also changed to providing more humanistic care to meet patients’ psychological needs.1 The notion that the patient is the center of the medical act has gradually become mainstream.2,3 Humanistic care not only empowers the health care giver to make patient-oriented decisions but also to move towards an empathetic, caring, respectful and kind model of clinical practice.2

“Humanistic care” as described by Paterson & Zderad is different from primary nursing.4–6 The definition of humanistic care involves concern, care, and attention to human personality; to meet people’s needs and respect human rights. It is concerned about the person’s spiritual problems; including the living conditions and spiritual development of self and others. Its essence is the human-centered thinking on existence, values, freedom and development. In addition to providing patients with the necessary medical and technical services, we also address their mental, cultural and emotional wellbeing.7–10 However, the society is currently more concerned about the progress of medical technology than humanistic care. Technological advances have tremendously altered the relationship between the patient and physician. The stethoscope is a valuable extension of doctors, although it is also widely viewed as creating distance with patients.11 The blind pursuit of financial profits at a systems-level has eroded patient-physician trust in China and medical disputes sometimes ignite a vicious cycle leading to violence.12 Violence in the medical workplace involves insults, threats, and attacks on medical staff. This not only affects the health and safety of medical staff, but also leads to poor health outcomes for patients.13 In 2016, a report from the China Joint Study Partnership proposed a reform strategy to improve health care and promote people-centred comprehensive care, aimed at reducing workplace violence.14

Humanistic care had been adopted in chronic disease care decades ago. Home-care and self-care movements can be seen as directed toward providing more humanistic care and promoting clients’ independence.15 Simpkin et al pointed out that the relationship between technology and humanistic care should be coordinated.11 Humanistic care is constantly being discussed and can be fostered by cultivating an open dialogue among patients, families, and health care staff.16 However, it is mostly used by nursing students and nurses to evaluate their skill level of patient care,17–20 but its implementation in general medicine is pending. There is a need for better humanistic care, but few approaches exist for strengthening its position,21,22 especially on cost-effectiveness, human personality and sociopolitical factors.15

Humanistic care is a soft skill that improves patient-physician relationships, strengthens communication, clears barriers, remodels physician’s image, and builds harmonious hospitals.23 This culture system has been ignored in our province or even country hospital. It is mainly exhibited at the moral level in the hospital, and is subjective; depending on the quality of medical staff, virtue, knowledge, etc. However, it is not adapted as standard operating practices.

The purpose of this study was to develop and validate a new measure that could be used to evaluate the level of humanistic care in a hospital in China. This was on the background of the comprehensive health care reform in Anhui Province. The objectives were to describe the process of designing and validating the instrument and to demonstrate the important role of humanistic care in public hospitals.

Methods

Development of Humanistic Care Evaluation Tool

We have developed a questionnaire in which the dimensions of humanistic care evaluation are set according to the “Further Improve Medical Service Action Plan in China”, and Doctor Relationship Questionnaire (PDRQ).24 Five dimensions were considered: medical treatment process, medical treatment environment, medical treatment experience, doctor-patient relationship, and overall evaluation. We selected commonly used items corresponding to the five dimensions which were suitable for inpatients and outpatients, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). The humanistic care evaluation tool is displayed in Table 1. The sum of the individual scores is the total score. A high score indicates a higher degree of humanistic care.

|

Table 1 Humanistic Care Evaluation Tool |

Validation of the Humanistic Care Evaluation Tool

A cross-sectional survey was conducted to evaluate the validity of the humanistic care evaluation tool. Three public hospitals were selected by simple random sampling (random number according to organization code), based on the geographical distribution and economic level: In Hefei-central and high economic level, Bengbu-north and lower economic level, Wuhu-south and middle economic level.

The survey was carried out in December 2019 and was divided into two stages: First, the outpatient respondents were selected by convenience sampling in each hospital. The number of respondents was ≥25 in each department (internal medicine, surgical, gynecology, obstetrics, and pediatrics) and ≥ 100 in each hospital. Secondly, inpatient respondents were selected by the same method as outpatient respondents. Pediatric patients were assisted by their parents or escorts.

Data Analysis

All collected questionnaires were input into a computer using the EpiData 3.1 software, and a consistency check was done to eliminate data entry errors. Descriptive statistics were performed on the data, and the results expressed as a percentage. Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated and used in the internal consistency of the humanistic care evaluation tool. Construct validity was tested the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Scores of humanistic care were calculated in factor analysis for all items, and divided into binary variables (>0 equal 1, <0 equal 0). Crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were determined to analyze the associations between characteristics and humanistic care using binary logistic regression. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and AMOS 24.0 version, and P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Since this was an observational study without any personal identifiable information, during the interview, they were informed that their participation was totally voluntarily they can withdraw from the research during the investigation process without providing any reason, and it had no any adverse effects on the study subjects, thus only verbal informed consent was obtained from the research subjects prior to study commencement. All procedures were undertaken following the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Verbal informed consents were recorded and the study protocol was approved by The Committee on Medical Ethics of The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval number: Quick -PJ 2019-10-20).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

A total of 312 outpatient and 323 inpatient respondents completed the questionnaire, with a respondent rate of 100%. Table 2 presents descriptive information about the respondents, nearly one-third were from three cities: 33.2% in Bengbu, 35% in Wuhu and 31.8% in Hefei. Approximately 50% of inpatients (50.9%) and outpatients (49.1%) were surveyed. Patients were drawn from various departments; internal medicine (32.6%), surgical (20%), gynecology and obstetrics (7.1%), pediatrics (16.4%), and 23.9% from other departments (ophthalmology, otolaryngology, stomatology, infectious diseases and Traditional Chinese Medicine). The majority of respondents were employers (31.6%), residents (66.9%), college and above (33.1%), and had a yearly income of 20,000–50,001 RMB (39.4%). Some respondents had a regular doctor (24.4%) while some used a community doctor (11.5%). About two-thirds of respondents (60.6%) experienced humanistic care.

|

Table 2 Characteristics of the Respondents |

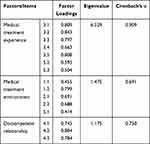

EFA

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.901, which meant that the factor analysis was suitable.25 According to the eigenvalue ≥ 1, three factors are finally obtained, and the explained total variance is 61.19%. Three factors formed the three dimensions of the scale: Factor 1 (medical treatment experience) included seven items (3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 5.2, 5.3), factor 2 (medical treatment environment) fie items (1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 5.1), factor 3 (doctor-patient relationship) three items (4.1, 4.2, 4.3). In total, the three factors described the three dimensions of the scale, and we adjusted the items, according to the result of factor analysis, and displayed the adjusted humanistic care evaluation tool in Table 3. All factors’ Cronbach’s α was above 0.600. The results of EFA were shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4 The Results of EFA (N=635) |

|

Table 3 Adjusted Humanistic Care Evaluation Tool |

CFA

Use structural equation model to test CFA. The results of the goodness-of-fit were: CMIN/DF (Chi-square minimum/degree of freedom) = 4.873;RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.078; GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) = 0.922, NFI (Normal Fit Index) = 0.917, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) =0.933, IFI (Incremental Fit Index) = 0.933, and TLI (Tucker Lewis Index) =0.915. The result showed acceptable construct validity.

Binary Logistic Regression

The results of logistic regression were shown in Table 5. Compared to Hefei, respondents in Bengbu experienced more humanistic care (OR = 3.52, 95% CI: 2.19, 5.66), but not as much in Wuhu (OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 0.90, 2.25). Inpatient respondents felt more humanistic care (OR= 2.00, 95% CI: 1.33, 3.00) compared to outpatients. Annual income was negatively associated with humanistic care (OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.66, 0.99), while having a regular doctor was positively associated with it (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.04, 2.51). Respondents who were “non-registered” as residents experienced a lower level of humanistic care compared to out-of-town residents (OR =0.47, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.89). The hospital department, education level and occupation were not significantly associated with humanistic care (P >0.05).

|

Table 5 Characteristics of the Respondents Linked with Humanistic Care (N = 635) |

Discussion

Currently, China is undergoing social transformation. However, conflicts between doctors and patients have not been effectively resolved; violent attacks against hospitals and medical personnel have increased.27 The doctor-patient relationship is not only a medical problem but more importantly, a social issue; the main cause being lack of humanistic care in hospitals. There are limited studies and a lack of theoretical basis on the issue. Therefore, it is necessary to use scientific methods to study the humanistic care experience of patients seeking medical care.

This study aimed at developing and validating humanistic care in Anhui province that could be used across Chinese public hospitals, and to reflect the humanistic care in public hospitals from patients’ perspective. The findings showed that the reliability and construct validity of the humanistic care evaluation tool developed were suitable Social determinants (location and yearly income), treatment style and having a regular doctor were significantly associated with the level of humanistic care. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in China to investigate such associations in humanistic care. Physical and psychological care must also be improved in addition to improving medical technology.28 The doctor-patient relationship has changed to the “patient-medical service system”; therefore, it is imperative to establish a good medical staff-patient relationship. This situation may reduce the patient’s trust in the doctor, and the ultimate lack of humanistic care. Patients who had a regular doctor were more likely to experience humane care. Patient’s expectations often exceed doctors’ abilities.29 Those not registered as residents and outpatients experienced lower level of humanistic care. Patients who had higher yearly income may have higher requirements for hospital standards. Plato once said that in the course of clinical practice, the best way is to combine scientific knowledge with individual trust, which forms a good doctor-patient relationship. It is more important to know what kind of patient has the disease than what disease the patient has.

Limitations

The study has several limitations: First, the study population was a convenient sample with low representation; which may deviate from the overall Chinese population. Second, the relationship was by pure association only, because of the nature of the cross-sectional study. Validation should also include criterion and content validity tests; more evidence is required to prove that the humanistic care evaluation tool has stable and good validity. Third, the lack of test-retest reliability is another limitation of our research. Additionally, other social determination factors, such as age and gender, were not included in the study, which may influence humanistic care.

Conclusions

These initial findings suggest that about two-thirds of the respondents experienced humanistic care. Both the reliability and construct validity of the humanistic care evaluation tool were suitable Social aspects (location and yearly income), treatment style and having a regular doctor were significantly associated with better humanistic care. These findings have important implications for further improving medical service in the Chinese public hospitals.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

The humanistic care tool in Anhui province can directly reflect the humanistic care from patients’ perspective, and can be popularized and applied across Chinese public hospitals. It is more scientific and objective to show humanistic care from the perspective of patients, which can further improve the medical service and doctor-patient relationship. It can guide the clinical practice of medical staff to be more standardized, reasonable and humanized. Humanistic care will empower the person in the clinical practice encounter to participate and make decisions related to patient health care. Humanistic care allow us to move towards an empathetic, caring, respectful and kind model of clinical practice.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Anhui Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission, the People’s Republic of China for supporting and cooperation. We would also like to thank all study participants for their time to be interviewed Xiaohu Wang and Yuqian Hu share first authorship.

Funding

This work was supported by Humanities and Social Science Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Anhui Province (No.SK2017A0166), and Medical Humanities Research Center Project of Anhui Medical University (No. YJSK202011).

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Du H-Z, Li K, Zhu H-J, et al. Long-term follow-up and humanistic care for patients with hypophyseal tumor. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2011;33:116–119.

2. Málaga G, Romero ZO, Málaga AS, Cuba-Fuentes S. Shared decision making and the promise of a respectful and equitable healthcare system in Peru. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2017;123–124:81–84. doi:10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.021

3. Capozzi JD, Rhodes R, Springfield DS. Ethical considerations in orthopaedic surgery. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:633–637.

4. Paterson JG, Zderad LT. Humanistic Nursing. NLN Publ; 1988.

5. Wu H-L, Volker DL. Humanistic nursing theory: application to hospice and palliative care. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):471–479. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05770.x

6. Boscart VM, Pringle D, Peter E, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the humanistic nurse-patient scale. Can J Aging. 2016;35:1–3.

7. Rogol AD. Clinical and humanistic aspects of growth hormone deficiency and growth-related disorders. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(Suppl 18):eS4–e10.

8. Whitley Bell K. In a language spoken and unspoken: nurturing our practice as humanistic clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(5):973–979. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.11.002

9. Watson JC. Treatment failure in humanistic and experiential psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(11):1117–1128. doi:10.1002/jclp.20849

10. Pettit ML. An analysis of the doctor-patient relationship using Patch Adams. J Sch Health. 2008;78(4):234–238. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00292.x

11. Simpkin AL, Dinardo PB, Pine E, Gaufberg E. Reconciling technology and humanistic care: lessons from the next generation of physicians. Med Teach. 2017;39(4):430–435. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270434

12. Tucker JD, Cheng Y, Wong B, et al. Patient-physician mistrust and violence against physicians in Guangdong Province, China: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008221. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008221

13. Hall BJ, Xiong P, Chang K, et al. Prevalence of medical workplace violence and the shortage of secondary and tertiary interventions among healthcare workers in China. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(6):516–518. doi:10.1136/jech-2016-208602

14. Zhang X, Li Y, Yang C, Jiang G. Trends in workplace violence involving health care professionals in China from 2000 to 2020: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e928393.

15. Anderson JM. Home care management in chronic illness and the self-care movement: an analysis of ideologies and economic processes influencing policy decisions. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1990;12:71–83. doi:10.1097/00012272-199001000-00010

16. Carnevale FA. Can critical care be delivered humanely? Leadersh Health Serv. 1993;2:16–19.

17. Ma F, Li J, Zhu D, et al. Confronting the caring crisis in clinical practice. Med Educ. 2013;47(10):1037–1047. doi:10.1111/medu.12250

18. Ma F, Li J, Liang H, et al. Baccalaureate nursing students’ perspectives on learning about caring in China: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):42. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-42

19. Wang C, Wu Q, Feng M, et al. International nursing: research on the correlation between empathy and china’s big five personality theory: implications for nursing leaders. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41:E1–E10.

20. Fenton MV. Development of the scale of humanistic nursing behaviors. Nurs Res. 1987;36(2):82–87. doi:10.1097/00006199-198703000-00003

21. Miller SZ, Schmidt HJ. The habit of humanism: a framework for making humanistic care a reflexive clinical skill. Acad Med. 1999;74(7):800–803. doi:10.1097/00001888-199907000-00014

22. Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286:1067–1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

23. Shapiro J. Walking a mile in their patients‘ shoes: empathy and othering in medical students‘ education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3(1):10. doi:10.1186/1747-5341-3-10

24. Garro LC. Physicians at work, patients in pain: biomedical practice and patient response in Mexico. Kaja Finkler. 1994;21:662–663.

25. Kaiser HF, Rice J. FORTRAN program for maximizing or minimizing the ratio of two quadratic forms. Educ Psychol Meas. 1973;33(3):735–737. doi:10.1177/001316447303300330

26. Jinshan Z, Licheng S, Zhongming X, et al. Statistical analysis of the questionnaire for light pollution at sea with SPSS. Int Conf Optoelectron Image Process. 2011:2:402–406.

27. Tian J, Du L. Microblogging violent attacks on medical staff in China: a case study of the longmen county people’s hospital incident. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):363. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2301-5

28. Rockey PH. Physicians’ well-being and safety: it’s not all about sleep. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1135–1136. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.001

29. Jensen PS. The doctor-patient relationship: headed for impasse or improvement? Ann Intern Med. 1981;95(6):769–771. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-95-6-769

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.