Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 13

Design and implementation of an empowerment model to prevent elder abuse: a randomized controlled trial

Authors Estebsari F , Dastoorpoor M , Mostafaei D, Khanjani N , Rahimi Khalifehkandi Z , Rahimi Foroushani A , Aghababaeian H , Taghdisi MH

Received 25 November 2017

Accepted for publication 20 February 2018

Published 17 April 2018 Volume 2018:13 Pages 669—679

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S158097

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Fatemeh Estebsari,1 Maryam Dastoorpoor,2 Davoud Mostafaei,3 Narges Khanjani,4 Zahra Rahimi Khalifehkandi,5 Abbas Rahimi Foroushani,6 Hamidreza Aghababaeian,7 Mohammad Hossein Taghdisi8

1Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 2Air Pollution and Respiratory Diseases Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, 3Department of Nursing Management, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 4Neurology Research Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, 5Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 6Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 7Nursing and Emergency Department, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, 8Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Older adults are more vulnerable to health risks than younger people and may get exposed to various dangers, including elder abuse. This study aimed to design and implement an empowerment educational intervention to prevent elder abuse.

Methods: This parallel randomized controlled trial was conducted in 2014–2016 for 18 months on 464 older adults aged above 60 years who visited health houses of 22 municipalities in Tehran. Data were collected using standard questionnaires, including the Elder Abuse-Knowledge Questionnaire, Health-Promoting Behavior Questionnaire, Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II, Barriers to Healthy Lifestyle, Perceived Social Support, Perceived Self-Efficacy, Loneliness Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale, and the SCARED (stress, coping, argument, resources, events, and dependence) tool. The intervention was done in twenty 45- to 60-minute training sessions over 6 months. Data analysis were performed using χ2 tests, multiple linear and logistic regression, and structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results: The frequency of knowledge of elder abuse, self-efficacy, social support and health promoting lifestyle before the intervention was similar in the two groups. However, the frequency of high knowledge of elder abuse (94.8% in the intervention group and 46.6% in the control group), high self-efficacy (82.8% and 7.8%, respectively), high social support (97.0% and 10.3%, respectively) and high health promoting lifestyle (97.0% and 10.3%, respectively) was significantly higher (P<0.001) and the frequency of elder abuse risk (28.0% and 49.6%, respectively) was significantly less in the intervention group after the intervention. SEM standardized beta (Sβ) showed that the intervention had the highest impact on increase social support (Sβ=0.80, β=48.64, SE=1.70, P<0.05), self-efficacy (Sβ=0.76, β=13.32, SE=0.52, P<0.05) and health promoting behaviors (Sβ=0.48, β=33.08, SE=2.26, P<0.05), respectively. The effect of the intervention on decrease of elder abuse risk was indirect and significant (Sβ=-0.406, β=-0.340, SE=0.03, P<0.05), and through social support, self-efficacy, and health promoting behaviors.

Conclusion: Educational interventions can be effective in preventing elder abuse.

Keywords: elder abuse, self-efficacy, social support, health promotion, health education

Introduction

The world’s population is rising, and the population of older adults is increasing rapidly as well, and their health and well-being require more attention.1 Due to physiological and anatomical changes caused by aging, the increase in physical and mental illnesses, social isolation due to retirement and disconnection with colleagues and friends, reduced social activity, low income, death of relatives and friends, and being away from children due to a number of factors, the older adults feel more lonely and depressed than other age groups.2 As a result, they are more vulnerable and subject to risks. One of these risks is elder abuse.3 Elder abuse, along with other indices such as life expectancy, is among the indicators of longevity and health.4 The World Health Organization describes elder abuse as any action or lack of appropriate action that causes injury or distress to an elderly person.5,6 Elder abuse is an indirect cause of death, and its evaluation is difficult.7 Elder abuse has many systemic and individual effects. Any injury or distress to elders can result in worsening of their health and well-being. Even minor injuries can have serious and permanent effects on their health.8 Elder abuse has different forms.9 While most people think that elder abuse is physical, there are other types of elder abuse: psychological, financial, and sexual abuse. Other types of harassment, such as exploitation, abandonment, and neglect, have also been raised.10

In some forms of elder abuse, the older adults have little or no insight into this problem or are unaware/unable to take care of themselves.11 Factors that affect elder abuse are sex, age, education level, marital status, housing status, lifestyle, social network and support, financial status, nutritional behavior, physical activity, sleep, leisure time, and recreation.12 Some of these factors can be controlled, and some are uncontrollable. Adopting health promoting behavior and implementing changes in lifestyle are feasible and have an impact on quality of life.13

Population aging is now an important public health issue in Iran.14 In the near future, Iran will face a high proportion of elders in its population. It is estimated that the population over >60 years in Iran in 2021 will be >10%; by 2025, the proportion aged >65 years will be 10.4%; and by 2050, this will become >20%.15 This increase in the elder population can cause a health crisis that the nation should be prepared for. One crisis may be elder abuse. Elders should be empowered against abuse by education.13 Empowerment is a health promotion concept and one of the strategies for healthy aging. Research has shown that if the elderly can equip themselves with skills and abilities that empower them, then they can protect themselves from health threats, including elder abuse.16

There is a view that empowerment education should focus on social support, self-efficacy, and health locus of control.12 Social support is one of the main health indicators of healthy aging and has a protective effect on disease. Self-efficacy is also an effective factor in healthy aging and can prevent elder abuse, along with other health promoting behavior and social support.2,17,18 Studies have confirmed the importance of self-efficacy as a determinant of health promoting behavior,19,20 while others have confirmed the relationship between social support and health promoting behavior20–22 and between self-efficacy and social support.20,23,24 The overall aim of this study was to design and evaluate the efficacy of an educational intervention for empowerment of the older adults, focusing on self-efficacy, social support, and health promoting behavior, in order to promote healthy aging and prevent elder abuse.

Purpose

The educational intervention in this study was designed focusing on older adult empowerment, and then its impact on self-efficacy, social support, health promoting behavior, and risk reduction was investigated. In addition, we investigated relationships among demographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors, perceived health status, feelings of loneliness, severity of depression, knowledge of elder abuse, health information sources, health barriers, health locus of control, and health promoting behavior, social support, self-efficacy, and level of elder abuse. The main hypothesis was to find out if the older adults that have social support and self-efficacy have more ability to adopt health promoting behavior and protect themselves from abuse.

Methods

Trial design

This study was a parallel randomized controlled educational trial study done on older adults. The study lasted for 18 months and was conducted in 2014–2016.

Participants

This study was conducted on 464 older adults aged >60 years who visited health centers in 22 municipalities of Tehran. Inclusion criteria for the participants were being >60 years of age, ability to speak Persian, lack of mental and psychological problems, and being aware of place and time. People were excluded if they did not want to participate in the study.

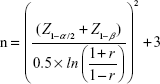

Sample size

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of education on health promoting behavior. Each relationship’s correlation coefficient was calculated, and the number of samples was determined based on the correlation coefficient matrix. The weakest significant correlation was 0.2. The sample size was determined based on Equation 1, assuming r=0.2, α=0.05, and β=0.2. The initial size was 193 in each group. Participants were selected from Tehran municipality health centers, and the elders of each health house had some correlated responses; therefore, the number of samples was multiplied by 1.2. We also considered a 15% chance of loss, so a total sample of at least 464 participants was calculated:

|

|

Randomization

In this study, participants were selected by two-stage cluster sampling. Based on the register of health houses in the 22 districts of Tehran, of 375, 44, ie, two health houses from each area, were selected randomly: one for the intervention group and the other for the control group. In each health house, from their list of older adults, 10–12 people were randomly selected (five men and five women or six men and six women). Eventually, 232 people were allocated to the intervention group and 232 to the control group. The intervention and control groups did not have any contact with each other.

Instruments

The following questionnaires were used to gather information in this study.

Demographic characteristics questionnaire

This included age, sex, marital status, education, type of housing, financial status (stable, unstable),25 type of health insurance, history of chronic disease, perceived health status (“How do you assess your overall health at the moment?”),26 and life companions (“Who do you live with now?”).

Elder abuse knowledge questionnaire

This measured the level of knowledge of participants about elder abuse and comprised 10 questions. This was a researcher-made questionnaire, based on Gironda et al’s27 and Almogue et al’s28 questionnaires. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire was evaluated and approved by the authors of this study before use. Cronbach’s α for this questionnaire was 0.84. The maximum score was 30. A score ≤15 was considered low knowledge, and a score >15 was considered good knowledge.

Health barriers questionnaire

A researcher-made questionnaire was drawn from the Barriers to Healthy Lifestyle Questionnaire29 and comprised eight questions. This asked about transportation, linguistic, cultural and belief barriers, health insurance, cost of living, dependence on others, knowledge about health resources, and preference for traditional or modern medicine. The score range for each question was from 1 to 4. A score >20 was considered high, and a score ≤20 was considered low. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire were evaluated and approved by the authors before use. Cronbach’s α for this questionnaire was 0.78.

Health promoting lifestyle profile II

This was designed by Walker et al and comprised six dimensions: physical activity, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal relationships, stress management, and health responsibility.54 The HPLP II is made up of 52 questions and scored based on a Likert scale.30 In this study, based on the median score, each health promoting behavior was divided into “desirable” and “undesirable” categories. This tool has been translated into various languages, including Persian. The content, construct, and criterion validity of this questionnaire have been approved in Persian and the Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.84.20,21 In this study, this validated questionnaire was used and based on the median score, each health-promoting behavior was divided into desirable and undesirable categories.

Personal resource questionnaire 85 – part 2

This was based on Weiss et al’s social protection theory31 and was used to measure perceived social support. The tool has five dimensions: intimacy, assistance, social integration, affirmation of worth, and nurturance. It comprises 25 items on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “I strongly disagree” to “I strongly agree”. The total score can be 25–175. This tool has been translated into Farsi, and its validity and reliability have been confirmed (Cronbach’s alpha =0.81).22 This validated questionnaire was used in the present study and the perceived social support score was divided into two desirable and undesirable categories based on the median cutoff point.

Schwarzer & Jerusalem general self-efficacy scale

This was used to measure perceived self-efficacy.32,33 The questions are answered on a 4-point Likert scale: “Not entirely correct”, “Rarely correct”, “Somewhat correct”, and “Completely correct”. The total score can be 10–40. A score of 10–20 indicates low self-efficacy, 20–30 average self-efficacy, and 30–40 high self-efficacy. This questionnaire has been translated into Persian and is valid and reliable to use in Persian and its Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.82. This validated questionnaire was used in this current study; however, low and average self-efficacy groups were merged and responses were divided into “desirable” and “undesirable” categories.

Loneliness scale

This questionnaire was created by the University of California, Los Angeles,34 and consists of 20 questions. Each question has three options: “never”, “sometimes”, and “often”. A score <35 in this questionnaire indicates a low sense of loneliness, 35–49 indicates a moderate sense of loneliness, and >50 indicates an intense sense of loneliness. This tool has been translated and validated in Persian by Pasha and Ismaili in 2007 and its Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.75.35 This validated questionnaire was used in the current study.

Geriatric depression scale

This was used to measure depression in the older adult.34 The questionnaire includes 15 questions with yes/no answers. A score <5 indicates no symptoms of depression, 5–10 indicates somewhat depressed, and >15 indicates moderate and severe depression.26 This questionnaire has been translated and validated in Persian by Malakouti et al in 2006 and it Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.90.36 This validated questionnaire was used in the current study.

Health locus of control scale

This is used to measure people’s beliefs and thoughts about the locus of control for health.33 It examines the health locus of control at three levels – internal, external, and chance control – with three types: A, B, and C. In this study, type A was used. This scale has 18 questions, of which six questions measure internal locus of control, six questions measure external locus of control, and six questions measure chance locus of control. A higher score in external control and chance control means that the individual sees his/her health more due to chance and external factors.33 Type A is used for healthy people, and its psychometric properties have been approved for use in Iran.37 The Cronbach’s alpha of the internal health locus of control (0.68), powerful others health locus of control (0.72), and chance health locus of control (0.66) subscales were moderately acceptable.37 This validated questionnaire was used in this study.

Assessment of elder at risk for abuse tool

This is a type of screening tool for identifying aged people at risk of elder abuse and determining that risk (vulnerability) of abuse. This tool was designed by the University of Ontario. It consists of six questions, each measuring one construct. These are stress level, coping, argument, resources, events, and dependence (SCARED). The total score can be 6–18. A score <7 means less vulnerable, 7–11 means somewhat vulnerable, and 12–18 means highly vulnerable to elder abuse.38 The authors of this study translated and retranslated the original questionnaire. The face validity and content validity of the questionnaire were determined by expert opinion. In order to determine the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire, the authors asked 110 people to complete the questionnaire. Cronbach’s α for the SCARED questionnaire was 0.74.

Data collection

A briefing was held beforehand for interviewers about how to complete the questionnaires. The questionnaries were completed before and after the intervention by trained instructors through face to face interviews and were completed simultaneously in both intervention and control groups. The questionnaires were kept confidential.

Intervention

The educational content for reducing the risk of elder abuse was designed based on results of the preintervention stage, opinions of health education experts, and a health promotion literature review. The older adults themselves also helped design the training program and were actively involved in setting up the program and implementing it.

The content of the educational interventions was based on the dimensions of health promoting behavior and comprised physical activity, recreation and entertainment, sleep, nutrition, interpersonal relations and social support, responsibility for health, mental health, and older adult stress management. These interventions were designed to improve and identify ways to strengthen self-efficacy, raise knowledge about elder abuse, its outcomes, risk factors, and causes, ways to reduce and combat abuse, benefits of health promoting behavior, barriers to conducting health promoting behavior, methods for removing barriers, identifying sources of support, and ways to receive support. In preparing this educational content, factors such as being easy, comprehensive, applicable, creating motivation, and acceptability for the older adult were considered. For each session, a particular topic was considered. Educational technology methods, such as lecture, question and answer, and problem-solving, were used.

The contents of the training were provided as CD, booklet, and pamphlet to the participants. A few short films provided by the Iranian Health Policy Council, Ministry of Health and Medical Education tailored to the content of the educational intervention were displayed. A number of educational messages were designed and sent to participants by text message. The official sources used for health promoting interventions included the Ministry of Health’s Healthy Lifestyle for Seniors: Principles of Healthy Aging booklet39 and elder abuse prevention protocols.38

After the educational package had been finalized, the educational intervention was performed. For each health house, at least 20 training sessions lasting 45–60 minutes were arranged. The total educational program took 6 months. In total, 600 hours’ training was provided for each person. Training was provided by health care professionals, and classes were held in health houses. Training was based on an adult education strategy.17 Three months after training was finished, the questionnaires were again completed by the two groups.

Outcomes

The effects of demographic factors, social support, self-efficacy, health status, information resources, source of control, perceived barriers, loneliness, and severity of depression on health promoting behavior were investigated, and then the effect of health promoting behavior on the risk of elder abuse was estimated.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was done using χ2 tests using multiple regression methods. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was also used to find direct, indirect, and total effects of each path, as well as standardized effects. In this analysis, fitness indicators – including the comparative fit index and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) – indicating the suitability of the model were calculated. These indicators should be >0.9. In this research, the model for preventing the risk of elder abuse was obtained based on the results of the initial data analysis (Figure 1). Data were analyzed using SPSS 21 and AMOS software, and the level of significance was <0.05.

| Figure 1 Conceptual framework of self-efficacy, social support, and health promoting behavior in reducing elder abuse. |

Ethical considerations

The project was approved by the ethics committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code 19230) and was registered in the Iranian Clinical Trials registry (IRCT2013070813904N1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All information remained confidential. Participants were able to withdraw at any time.

Results

The mean age of participants was 65.9±3.6 years. The majority were married (57.3%) and had an educational degree less than a high school diploma (75.2%). Also, 57.3% (266 people) lived with their spouse and children. Regarding the question “How do you assess your health in the present?”, most reported that their health status was excellent (63.4%). The distribution of the demographic, social, economic, and clinical characteristics of the intervention and control groups was similar before the intervention (Table 1).

| Table 1 Baseline characteristics of participants in the intervention and control groups |

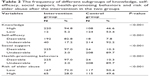

The frequency of knowledge of elder abuse, self-efficacy, social support, health promoting behavior, and risk of elder abuse before the intervention was similar in the two groups. However, frequency of these variables in two groups was significantly different after intervention (P<0.001). Most of those in the intervention group received a more favorable score than the control group after intervention (Table 2).

| Table 2 The frequency of different subgroups of knowledge, self-efficacy, social support, health-promoting behaviors and risk of elder abuse after the intervention in the two groups |

The effect of educational intervention on self-efficacy, social support, and health promoting behavior (after intervention) and after control for variables before the intervention (sex, age, marital status, educational level, housing ownership, financial status, life structure, history of chronic illness, insurance, date of last referral to a physician, health status, information resources, health barriers, depression rate, loneliness, health locus of control, and amount of knowledge of elder abuse) was estimated using backward logistic and linear regression analyses.

The results of logistic and linear regression showed that there was a significant relationship between self-efficacy and health promoting behavior (after the intervention) with receiving the intervention, age, and education. Also, in the logistic model, social support (after the intervention) showed a significant relationship with intervention, sex, and health status (Table 3). These significant variables entered SEM. As such, the primary model of self-efficacy, health promoting behavior and social support in preventing the risk of elder abuse was modified (Figure 2). For each path, the unstandardized coefficient was calculated. Positive and negative signs for each path indicated that for a 1-unit increase in each variable, the other variable’s score increased or decreased. The GFI of the original SEM model was tested. GFI of 0.79 and incremental fit index of 0.78 indicated the fitness of the model. The standardized coefficients (Sβ) of the model showed that the effect of the intervention was primarily on social support (Sβ=0.80, β=48.64, SE=1.70) than on self-efficacy (Sβ=0.76, β=13.32, SE=0.52) and ultimately health promoting behavior (Sβ=0.48, β=33.08, SE=2.26) (Figure 2).

The adjusted SEM model for the prevention of elder abuse was fitted again after removing insignificant variables. The final SEM model is presented in Figure 3. The GFI of the final model was tested, and the indicators GFI of 0.9 and incremental fit index of 0.91 showed good fit. The results of the final model showed that receiving intervention, perceived health status, educational level, social support, and self-efficacy had an indirect effect on the risk of elder abuse. The intervention did not directly affect the risk of elder abuse, but this variable directly affected self-efficacy and social support, and these affected health promoting behavior. The effect of intervention on decrease of elder abuse risk was indirect and significant (Sβ=−0.406, β=−0.340, SE=0.03, P<0.05), and through social support, self-efficacy, and health-promoting behaviors. Finally, only health-promoting behaviors (HPB) had a direct impact on the risk of elder abuse.

Discussion

Various types of interventions have been designed and implemented with a variety of strategies, including educational, supportive, and legal strategies, for addressing the problem of elder abuse.40 In general, interventions in the area of primary or secondary prevention of elder abuse are divided into two broad categories. The first of these is interventions that are aimed at reducing the burden of abuse on the older adults and improving their health. These interventions are known as “elder-centered” strategies for empowering the elderly by using health promoting strategies, such as social support, self-efficacy, and health promoting behavior. The focus of this current study was on the design and implementation of these interventions. The second category of interventions is empowerment of the staff of health centers and organizations related to the health of the older adults in the area of primary prevention, in order to reduce the risk of elder abuse.41

The focus of this current study was on the design and implementation of the first category interventions. In this study, knowledge in the field of elder abuse, self-efficacy, perceived social support, and health promoting behavior significantly improved in the intervention group. The results of this study are consistent with other studies that showed that educational interventions can be effective in improving elders’ abuse-related knowledge,27,28,42–45 and intervention programs for prevention of elder abuse can lead to short-term improvements in the level of knowledge of the older adult in the field of elder abuse.

In this study, the self-efficacy score in the intervention group significantly increased, though self-efficacy scores in the two groups were mostly at an undesirable level before the intervention. Self-efficacy was used to increase health promoting behavior and to develop behavioral changes in the prevention of elder abuse in the target group. Self-efficacy directly promotes health promoting behavior through efficient expectations and indirectly affects planned behavioral change by influencing perceived barriers.46 Self-efficacy is an important factor in interventions aimed at changing unhealthy behavior and creating and maintaining healthy behavior. A person can make a behavioral change only if they believe that they are able to change.19,47

Score for perceived social support for elder abuse risk reduction increased in the intervention group. These results are consistent with other studies that showed that educational interventions are effective in improving perceived social support for the older adult.47,48 Social support is the strongest coping force to successfully cope with chronic diseases and stressful living conditions.48,49 Social protection has two levels: understanding support and getting it. Among older people, understanding social support is more important than getting it. In many cases, there are social support resources, such as the family and the community, but the older adults do not receive favorable support for a variety of reasons, as they do not realize that they need help and should get help from someone. Several factors, such as cultural beliefs and elders’ beliefs, affect the understanding of their need for social support. Thinking about having independence and not imposing oneself on others are among the mental beliefs of the older adult and the most important obstacle to understanding their need for social support. If elderly people find themselves in situations requiring support and seek social support, then they will suffer less, because social support reduces their stress and improves their mental health.50,51 Research has shown that older people with more social support have better mental health.12

Health promoting behavior in terms of decreasing the risk of elder abuse was significantly higher in the group that received intervention. Health promoting behavior is among the major determinants of health and is directly associated with the prevention of disease.12 In order to cope with elder abuse, the elderly must have physical, psychological, and social well-being. In numerous studies, it has been proven that the adoption of health promoting behavior increases the quality of physical and mental health and reduces susceptibility to elder abuse.12

The intervention caused a significant increase in self-efficacy, social support, and health promoting behavior. The SEM showed that the effects of educational interventions on perceived social support, self-efficacy, and health promoting behavior were not the same. Interventions had a greater impact on social protection than self-efficacy or health promoting behavior. This finding is very important, because it shows that in designing interventions to create behavioral changes, perceived social support and self-efficacy should be considered as important factors.

The final SEM model also showed that people with higher self-efficacy had a higher chance of understanding and gaining social support, and this resulted in more behavioral changes. The results of this study are consistent with other studies13,31 that showed that those who had more efficacy and perceived and received social support were more likely to change behavior. Another finding from the present study was that interventions are effective in reducing the risk of elder abuse in the older adult, and the risk score among the older adult in the intervention group decreased after the intervention. The coefficients of SEM showed that the path coefficient of health promoting behavior to elder abuse risk was −0.01; and for every 1-unit increase in health promoting behavior score, the average risk of elder abuse decreased by 0.01.

The SEM model showed that the effect of interventions on elder abuse was indirectly and significantly determined through social support, self-efficacy, and health promoting behavior. However, the impact of health promoting behavior on the risk of elder abuse was direct. In other words, older adults can protect themselves against the threats of elder abuse if they have health promoting behavior and the older adults who take care of their health and get through life better than others. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of other studies.52,53

The results of this study show a model for prevention of elder abuse. The GFI of the model was also tested statistically and showed its relevance. Most likely, this is the first research to use SEM to reduce the risk of elder abuse. The use of conceptual frameworks and planning to understand the factors associated with reducing the risk of elder abuse plays an important role in improving the quality of interventions. A limitation was that there was no follow-up to examine the long-term effects of the intervention on quality of life or health status of the target group. Other limitations of this study are lack of blinding, probable social desirability bias, volunteer bias, selection bias, and limited international and external validity of the findings.

Conclusion

The increasing number of older adults and changes in culture, household structure, and lifestyle have increased the incidence of misconduct and elder abuse. Therefore, we need more understanding of the reasons for elder abuse and accurate planning for preventing it. In Iran, due to the cultural and religious context in which respect for older adults is emphasized, families are the most important and the original providers of emotional and psychological care for the older adult. For this reason, it is likely that in the absence of government attention and support, families are under pressure and experience trouble, which may increase the likelihood of elder abuse. The results of this study indicate a positive and significant effect of intervention based on empowerment of the elderly in improving health promoting behavior and reducing the risk of elder abuse. Therefore, organized and short-term training courses on elder abuse, risk factors, and methods for reducing it for all age groups can be effective in preventing this phenomenon. It is recommended that educational interventions for the prevention of elder abuse be started before reaching an advanced age. In addition, interventions focusing on the health system should be considered, in order to empower employees of health centers and organization in preventing elder abuse. Interventions focused on the health services system can sensitize health care providers, encourage them to do routine examinations, and design and implement management protocols for the older adult.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a PhD thesis at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to thank the individuals who participated in the study. This work was funded and supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), grant 19230.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Dadkhah A. Aging care system in America and Japan and to present indicators for strategic planning at Iran’s aging services. Iran J Ageing. 2007;2:166–176. | ||

Liu L, Gou Z, Zuo J. Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:750–758. | ||

Suraj S, Singh A. Study of sense of coherence health promoting behaviour in north Indian students. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:645–652. | ||

Fraga S, Lindert J, Barros H, et al. Elder abuse and socioeconomic inequalities: a multilevel study in 7 European countries. Prev Med. 2014;61:42–47. | ||

Biggs S, Haapala I. Theoretical development and elder mistreatment: spreading awareness and conceptual complexity in examining the management of socio-emotional boundaries. Ageing Int. 2010;35:171–184. | ||

Strasser S, King P, Payne B, O’Quin K. Elder abuse: what coroners know and need to know. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013;25:242–253. | ||

Bond M, Butler K. Elder abuse and neglect: definitions epidemiology and approaches to emergency department screening. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:257–273. | ||

Dong XQ, Chen RJ, Chang ES, Simon MA. Elder abuse and psychological well-being: a systematic review and implications for research and policy: a mini review. Gerontology. 2013;59:132–142. | ||

Lindert J, Luna J, Torres-Gonzalez F, et al. Study design sampling and assessment methods of the European study ‘abuse of the elderly in the European region’. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:662–666. | ||

Peterson JC, Burnes DP, Caccamise PL, et al. Financial exploitation of older adults: a population-based prevalence study. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1615–1623. | ||

O’Brien JG, O’Neill D. Prevention of elder abuse. Lancet. 2011;377:2005–2006. | ||

Södergren M. Lifestyle predictors of healthy ageing in men. Maturitas. 2013;75:113–117. | ||

van Malderen L, Mets T, Gorus E. Interventions to enhance the quality of life of older people in residential long-term care: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:141–150. | ||

Momtaz YA, Hamid TA, Ibrahim R. Theories and measures of elder abuse. Psychogeriatrics. 2013;13:182–188. | ||

Rasel M, Ardalan A. Future costs of aging and health services: a warning for the country’s health system. Iran J Ageing. 2007;2(2):300–305. | ||

Dong XQ, Chang ES, Wong E, Wong B, Simon MA. Association of depressive symptomatology and elder mistreatment in a US Chinese population: findings from a community-based participatory research study. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2014;23:81–98. | ||

Estebsari F, Taghdisi MH, Foroushani AR, Eftekhar HE, Shojaeizadeh D. An educational program based on the successful aging approach on health-promoting behaviors in the elderly: a clinical trial study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e16314. | ||

Harvey IS, Alexander K. Perceived social support and preventive health behavioral outcomes among older women. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2012;27:275–290. | ||

Azadbakht M, Garmaroodi G, Tanjani PT, Sahaf R, Shojaeizade D, Gheisvandi E. Health promoting self-care behaviors and its [sic] related factors in elderly: application of health belief model. J Educ Community Health. 2014;1:20–29. | ||

Foroushani AR, Estebsari F, Mostafaei D, et al. The effect of health promoting intervention on healthy lifestyle and social support in elders: a clinical trial study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e18399. | ||

Baheiraei A, Mirghafourvand M, Charandabi SM, Mohammadi E, Nedjat S. Health-promoting behaviors and social support in Iranian women of reproductive age: a sequential explanatory mixed methods study. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:465–473. | ||

Baheiraei A, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammadi E, et al. Health-promoting behaviors and social support of women of reproductive age and strategies for advancing their health: protocol for a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:191. | ||

Shao YC, Liang L, Shi LJ, Wan CS, Yu SY. The effect of social support on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and adherence. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:2804178. | ||

Taghdisi MH, Latifi M, Afkari ME, Dastoorpour M, Estebsari F, Jamalzadeh F. The impact of educational intervention to increase self efficacy and awareness for the prevention of domestic violence against women. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2015;3:32–38. | ||

Ay S, Yanikkerem E, Calim SI, Yazici M. Health-promoting lifestyle behaviour for cancer prevention of Turkish university students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2269–2277. | ||

Aqtash S, van Servellen G. Determinants of health-promoting lifestyle behaviors among Arab immigrants from the region of the Levant. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36:466–477. | ||

Gironda MW, Lefever KH, Anderson EA. Dental students’ knowledge about elder abuse and neglect and the reporting responsibilities of dentists. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:824–829. | ||

Almogue A, Weiss A, Marcus EL, Beloosesky Y. Attitudes and knowledge of medical and nursing staff toward elder abuse. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:86–91. | ||

Sajwani RA, Shoukat S, Raza R, et al. Knowledge and practice of healthy lifestyle and dietary habits in medical and non-medical students of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:650–655. | ||

Hulsman BL. The Relationship between Self-Directedness and Health Promotion Behaviors in the Elderly [doctoral thesis]. Knoxville (TN): University of Tennessee; 2011. | ||

Weiss JA, Robinson S, Fung S, Tint A, Chalmers P, Lunsky Y. Family hardiness, social support, and self-efficacy in mothers of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7:1310–1317. | ||

Nezami E, Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M [webpage on the Internet]. Persian adaptation (Farsi) of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. 1996. Available from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/persean.htm. Accessed March 5, 2018. | ||

Martinelli AM. An explanatory model of variables influencing health promotion behaviors in smoking and nonsmoking college students. Public Health Nurs. 1999;16:263–269. | ||

Oni OO [webpage on the Internet]. Social support, loneliness, and depression in the elderly. 2010. Available from: http://qspace.library.queensu.ca/handle/1974/6047. Accessed March 5, 2018. | ||

Hojat M. Loneliness as a function of parent-child and peer relations. J Psychol. 1982;112:129–133. | ||

Malakouti K, Fathollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Salavati M, Kahani S. Validation of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) in Iran. Res Med. 2006;30:361–369. | ||

Moshki M, Ghofranipour F, Hajizadeh E, Azadfallah P. Validity and reliability of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale for college students. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:295. | ||

Southwestern Ontario Regional Elder Abuse Network. Guidelines for developing elder abuse protocols: a southwest Ontario approach. 2011. Available from: http://www.thehealthline.ca/pdfs/ElderAbuseGuidelines2011.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2018. | ||

Halloran L. Healthy aging: clinical and lifestyle considerations. J Nurse Pract. 2012;8:77–78. | ||

Pillemer K, Burnes D, Riffin C, Lachs MS. Elder abuse: global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 2):S194–S205. | ||

Choo WY, Hairi NN, Sooryanarayana R, et al. Elder mistreatment in a community dwelling population: the Malaysian Elder Mistreatment Project (MAESTRO) cohort study protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011057. | ||

Hoover RM, Polson M. Detecting elder abuse and neglect: assessment and intervention. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:453–460. | ||

Owotade FJ, Ogundipe OK, Ugboko VI, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and attitude on cleft lip and palate among antenatal clinic attendees of tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:6–9. | ||

Simone L, Wettstein A, Senn O, Rosemann T, Hasler S. Types of abuse and risk factors associated with elder abuse. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14273. | ||

Wang XM, Brisbin S, Loo T, Straus S. Elder abuse: an approach to identification assessment and intervention. CMAJ. 2015;187:575–581. | ||

Liu N, Ai X, Cao Y, Zhang Y. [Understanding the elder abuse by family members]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;37:419–423. Chinese. | ||

Khaledi GH, Mostafavi F, Eslami AA, Afza HR, Mostafavi F, Akbar H. Evaluation of the effect of perceived social support on promoting self-care behaviors of heart failure patients referred to the Cardiovascular Research Center of Isfahan. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:e22525. | ||

Chamberlain L. Perceived social support and self-care in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16:753–761. | ||

Salyer J, Schubert CM, Chiaranai C. Supportive relationships self-care confidence and heart failure self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27:384–393. | ||

Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:491–499. | ||

Montes-Berges B, Augusto JM. Exploring the relationship between perceived emotional intelligence coping social support and mental health in nursing students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:163–171. | ||

Dong XQ, Simon MA. Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology. 2013;59:464–472. | ||

Haghighatian M, Fotouhi M. Sociocultural factors affecting elderly abuse. J Health System Res. 2013;8:1117–1126. | ||

Walker S, Sechrist K, Pender N. Health promoting lifestyle profile II. Omaha (NE): University of Nebraska at Omaha; 1995. Available from: https://www.unmc.edu/nursing/faculty/health-promoting-lifestyle-profile-II.html. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.