Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 9

Cutaneous factitia in elderly patients: alarm signal for psychiatric disorders

Authors Chiriac A , Foia L , Birsan C, Goriuc A, Solovan C

Received 18 October 2013

Accepted for publication 6 November 2013

Published 12 March 2014 Volume 2014:9 Pages 421—424

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S56185

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Anca Chiriac,1 Liliana Foia,2 Cristina Birsan,1 Ancuta Goriuc,2 Caius Solovan3

1Department of Dermatology, Nicolina Medical Center, Iaşi, Romania; 2Surgical Department, Grigore T Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iaşi, Romania; 3Department of Dermatology, Victor Babeş University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timişoara, Romania

Background: The factitious disorders, more commonly known in daily practice as pathomimia, are expressed in dermatology units by skin lesions induced voluntarily by the patient, in order to draw attention of the medical staff and/or the family members. The disorder is often challenging to diagnose and even more difficult to document in front of the patient or relatives. It represents a challenge for the physician, and any attempt at treatment may be followed by recurrence of the self-mutilation. This paper describes two cases of pathomimia diagnosed by dermatologists and treated in a psychiatry unit, highlighting the importance of collaboration in these situations.

Patients and methods: Two case reports, describing old female patients with pathomimia, hospitalized in a department of dermatology for bizarre skin lesions.

Results: The first case was a 77-year-old female with unknown psychiatric problems and atrophic skin lesions on the face, self-induced for many months, with multiple hospitalizations in dermatology units, with no response to different therapeutic patterns, and full recovery after psychiatric treatment for a major depressive syndrome. The second case was a 61-year-old female patient with disseminated atrophic scars on the face, trunk, and limbs. She raised our interest because of possible psychiatric issues, as she had attempted to commit suicide. The prescription of antidepressants led to a significant clinical improvement.

Conclusion: These cases indicate that a real psychiatric disease may be recorded in patients suffering from pathomimia. Therefore, complete psychiatric evaluation in order to choose the proper therapy is mandatory for all these cases. Dermatologists and all physicians who take care of old patients must recognize the disorder in order to provide optimum care for this chronic condition. We emphasize therefore the importance of psychiatric evaluation and treatment to avoid the major risk of suicide. Skin lesions must be regarded as an alarm signal in critical cases, especially in senior people.

Keywords: pathomimia, elderly, psychiatric disorders

Case reports

Case 1

A 77-year-old woman was hospitalized in a dermatology department for atrophic skin lesions, with discrete erythema at the edges on the preauricular area and hyperpigmented macules on the frontal and malar area (Figure 1). She described the lesions as being present for several months, accompanied by slight pruritus on the face and scalp. The patient was diagnosed 10 years before with arterial hypertension well controlled by indapamide; a cardiological examination revealed no anomaly or no neurological symptoms. Dermatological examination failed to unfold other skin lesions, except the one on the face strictly related to the patient’s age.

| Figure 1 Scars with irregular borders, slight erythema, hyperpigmented postinflammatory scars on the pre-auricular area on the face. |

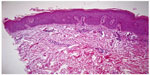

She was referred to the hospital under suspicion of discoid lupus; a punch biopsy was taken from the preauricular area. The histopathological report excluded lupus and concluded orthokeratosis, spongiosis, and sparse lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 Ortokeratosis, spongiosis, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, thickening of basal membrane (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×). |

All the routine lab tests were within normal range. Based on clinical grounds, histological report, and lab investigations, the suspicion of discoid lupus was excluded. A psychiatric consult was demanded, and a transfer to the psychiatric department was accepted. New dermatological advice was asked for 1 month later, the patient being in very good condition, with no new lesions and minor hyperpigmentation on the face. The patient admitted the self-mutilation by causing the skin lesions herself, but without being able to explain the automutilation, most of the time being unaware of doing it; furthermore, she did not claim any delusions of parasitosis. She was transferred to the psychiatric unit and not followed up in the dermatology unit.

Case 2

A 61-year-old woman was hospitalized in a dermatology department for evaluation of atrophic scars disseminated on the face, trunk, and upper limbs (Figure 3). She could not recall when she had first noticed the lesions, but her medical documents were filled with hospitalizations, investigations, and therapies for the last 2 years, varying from chronic eczema, anetoderma, morphea, prurigo, discoid lupus erythematosus, mycosis fungoides, and others not remembered by the patient. The patient was in good medical condition, with no comorbidities, treatments, or complaints. Clinical examination did not reveal anything worthy.

| Figure 3 Atrophic scars on the face, trunk, and shoulders. |

A complete battery of blood tests was performed, but did not reveal the cause of the disorder. On the fifth day of hospitalization, during the night, she attempted suicide by taking an aspirin overdose. She was transferred to a psychiatric hospital, where she was diagnosed with severe depressive syndrome. Thereafter, she underwent stabilization and treatment, with no information on the therapeutic plan being available. The patient finally admitted the self-mutilation that had been going on for years.

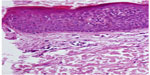

Based on the elusive history of the lesions, chronic evolution, and weird cutaneous impairments displayed upon attainable areas of the body, which did not mirror any of the known dermatoses, and associated to inconclusive biopsy (Figure 4), with remission after specific psychiatric therapy, we finally reached a diagnosis of factitial dermatitis.

| Figure 4 Parakeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and a few lymphocytes scattered in the dermis. |

Discussion

Psychocutaneous disorders are conditions that are characterized by psychiatric and skin manifestations, and are classified into primary dermatologic disorders with psychiatric comorbidity (atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, vitiligo, alopecia areata) and psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations (obsessive–compulsive disorders, factitious disorder by self-mutilation, delusions of parasitosis, psychogenic purpura, cutaneous sensory disorders, and others).1

Factitious disorder is a mental disease, and the number of patients requiring medical care for it is probably quite consistent but however is rather unknown, partly caused by misrecognition of the clinical and psychopathological features.2,3 Cutaneous factitia is not very well known, can mimic many skin lesions, and may lead to unnecessary investigations and treatments, therefore delaying the diagnosis and correct therapeutic measures in psychiatric hospitals.

Other related terms mostly used in dermatology and reflecting the skin condition in these pathological cases are: dermatitis artefacta syndrome, characterized by unconscious self-injury of normal skin, while dermatitis para-artefacta is the result of autoaggravating a preexisting dermatosis.4 It is more often described in women; the ratio varies from 4:1 to 8:1, with age of onset ranging from 9 to 73 years.5

The patient in general does not accept the idea of having a psychiatric disorder, and it is sometimes quite difficult to convince the family as well. Skin lesions are produced in different ways, depending on the education and imaginative levels of each person – scarifications, cuts, burns – and are usually not admitted to by the patient.

Factitious disorders must be differentiated from malingering; an important clue for this is that malingering is based on a real individual motivation (avoiding work, military or social duty, prison; obtaining material recompense, cost reparation, drugs), while patients suffering from factitia need medical care and support, claiming attention from medical staff and members of their own families.6

Morgellons disease is a controversial condition in which patients complain of stinging, burning, and biting sensations under the skin and presence of subcutaneous dermal fibers.7 It has been associated with positive serology to Borrelia burgdorferi, and recently these filaments proved to be composed of keratin and products of keratinocytes.8

Lichen simplex chronicus is characterized by lichenified plaque due to prolonged scratching, on the neck (cervical and occipital area), elbow, ankles, and vulva, in patients with psychological disorders.9,10

Prurigo nodularis is characterized clinically by chronic, intensely pruritic nodules, with hyperpigmentation, with unknown etiology, most commonly seen between the ages of 20 and 60 years, with equal distribution between the sexes, associated with emotional stress, anemia, hepatic dysfunction, uremia, myxedema, venous stasis, folliculitis, nummular eczema, lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus infection, perforating collagenosis, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, contact dermatitis, and atopic eczema.11

Differential diagnosis also included the delusion of parasitosis, a quite frequent clinical entity, but where patients have the fixed, false belief that they are infested with parasites or have foreign objects walking through their skin, despite the almost normal aspect of the skin (sometimes scratch marks and slight erythema).

Self-induced skin damage can represent a real challenge to dermatologists. The history of the disorder is often quite ambiguous and misleading, but despite the fact that our knowledge of this peculiar pathology is limited, the mainstay of the diagnosis must always be kept in mind. Moreover, based on our knowledge and clinical experience, patients with cutaneous factitia are in general, individuals with a high level of education, and are seeking attention. Treatment is challenging, due to a characteristic lack of response to even prolonged therapy; the curative goal and success depends mostly upon psychiatric evaluation and treatment, which are rather difficult to achieve, and frustrating to both physicians and patients.

Clinical suspicion of factitia is based on the following clues: ambiguous history of the lesions, chronic evolution, bizarre forms of skin lesions that are found on accessible parts of the body and that do not resemble any of the known dermatoses, the continuous denial of the self-induced injury, healing of the skin under occlusive dressing, and finally the psychiatric evaluation.

Skin lesions must be considered an alarm signal in critical cases with emotional and behavior modifications, and particular attention should be paid especially in aged patients, while dermatologist–psychiatrist work teams are the major foundation of resolving these cases.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(4):247–257. | |

Bordes G, Schuster JP, Limosin F. Depressive symptoms in pathomimia: comorbidity or psychiatric factitious disorder? Encephale. 2011;37(2):133–137. | |

Hlal H, Barrimi M, Kettani N, Rammouz I, Aalouane R. [“Factitious disorder and skin picking: clinical approach.” A case report]. Encephale. Epub September 30, 2013. | |

Novak TG, Duvancić T, Vucić M. Dermatitis artefacta: case report. Acta Clin Croat. 2013;52(2):247–250. | |

Stein DJ, Hollander E. Dermatology and conditions related to obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(2 Pt 1):237–242. | |

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC). Malingering and factitious disorders and illnesses, active component, US. Armed Forces, 1998–2012. MSMR. 2013;20(7):20–24. | |

Savely VR, Stricker RB. Morgellons disease: analysis of a population with clinically confirmed microscopic subcutaneous fibers of unknown etiology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;3:67–78. | |

Middelveen MJ, Mayne PJ, Kahn DG, Stricker RB. Characterization and evolution of dermal filaments from patients with Morgellons disease. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:1–21. | |

Ermertcan AT, Gencoglan G, Temeltas G, Horasan GD, Deveci A, Ozturk F. Sexual dysfunction in female patients with neurodermatitis. J Androl. 2011;32(2):165–169. | |

Burgin S. Nummular eczema and lichen simplex chronicus/prurigo nodularis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008:158–162. | |

Accioly-Filho LW, Nogueira A, Ramos-e-Silva M. Prurigo nodularis of Hyde: an update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14(2):75–82. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.