Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 14

Coping with Everyday Life for Home-Dwelling Persons with Dementia: A Qualitative Study

Authors Moe A , Alnes RE, Nordtug B, Blindheim K , Steinsheim G , Malmedal W

Received 6 January 2021

Accepted for publication 3 March 2021

Published 23 April 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 909—918

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S300676

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Aud Moe,1 Rigmor Einang Alnes,2 Bente Nordtug,3 Kari Blindheim,1,2 Gunn Steinsheim,4,5 Wenche Malmedal1,4

1Centre of Care Research Central Norway, Faculty of Health Science, Nord University, Bodø, Norway; 2Department of Health Sciences Ålesund, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Ålesund, Norway; 3Faculty of Health Science, Nord University, Bodø, Norway; 4Department of Public Health and Nursing, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway; 5Centre for Development of Institutional and Home Care Services, Åfjord, Norway

Correspondence: Aud Moe

Centre of Care Research, Faculty of Nursing and Health Science, Nord University, Postbox 1490, Bodø, N-8049, Norway

Tel +47 911 31 163

Email [email protected]

Aim: This study aimed to gain insight into factors that influence everyday coping strategies as described by persons with early to intermediate dementia.

Background: Living with dementia presents difficulties coping with everyday life. This study focuses on coping with everyday life for persons with mild to moderate dementia in order to facilitate their ability to live at home.

Design: A qualitative study.

Methods: Individual interviews with 12 persons with dementia were conducted in their own homes.

Findings: Coping with everyday life can be influenced by the experience of the diagnostic process and by information about dementia. It can also be affected by stigmatization of persons with dementia, as well as by challenges in everyday life. In addition, challenges in receiving help may include poor continuity of services and healthcare staff with limited competence. By contrast, person-centered care led to positive experiences that supported everyday coping skills. Most of the respondents wanted to participate in day care several days a week. Other positive experiences were making new friends and participating in meaningful activities; such experiences could enhance to coping strategies.

Conclusion: To strengthen everyday coping for persons with dementia living at home, there is a need for openness about the disease. Follow-up for persons with dementia must be carried out by reputable professionals trained and educated in dementia care. Finally, the municipalities must have contact persons, dementia coordinator/-team, who are available for persons with dementia at the time of diagnosis position and afterwards.

Keywords: coping, dementia diagnosis, everyday life, health care services, meaningful days

Introduction

It is estimated that approximately 50 million people worldwide currently suffer from dementia, and this number is projected to increase to about 82 million by 2030.1 In Norway, persons with dementia in an early or intermediate stage are expected to live in their own homes.2 The home environment can be a place to experience independence and retain quality of life,3 which are both facilitated when the person with dementia masters everyday life. This study focuses on coping with everyday life for persons with mild to moderate dementia living in their own homes.

A study of consequences in daily life for persons with mild cognitive impairment found that cognitive changes could be burdensome and alter their activity patterns.4 Living with dementia can also make it difficult to cope with everyday life.5 Several studies have explored the challenges of dementia,4,6 while others have confirmed that life can still have positive aspects following this diagnosis.5,7,8 In this context, predicting self-esteem is a positive dimension8 and can be understood as an active process that is integral to living and maintaining well-being and quality of life.7,8 Living and coping positively with dementia was related to experiences of engaging with life rather than explicitly to living with dementia.7 A review study by Bjørkløf et al,9 that included 79 articles, found that humor and practical and emotional support were important for living with dementia.

In addition various forms of day care can make important contributions to home–based care for persons with dementia.10–12 In Norway day care centers are perceived as significant service for helping persons with dementia to continue living at home.13 Day care activities may include physical activities,13 farm–based care14 and intergenerational activities.15 Singing and music also have the potential to evoke emotions and reactions16 and welfare technology can support managing everyday life.17–19 Contributions from volunteers are also important for experiencing coping in everyday life for persons with dementia.20

According to Folkman and Lazarus there are different strategies for coping in stressful situations.21 A review study of older persons, including those with cognitive dysfunction, found association between resources and strategies for coping and depression.22 Another study has found that coping with stress is facilitated by self-determination23 and that coping strategies can be used to re-construct one’s sense of self.24

Understanding the positive experiences, strengths and capabilities that persons with dementia might retain is important for enhancing conceptual accounts of well-being and quality of life, as well as for person-centered care.25,26 Just a few original studies have described coping for persons with dementia.9 Knowledge about coping is valuable for all professionals involved in the provision of services to people with dementia, and thereby important for the quality of the services. This study aimed to gain insight into factors that influence everyday coping as described by persons with early/moderate stage of dementia.

Materials and Methods

The rationale of this study was to bring out experiences from persons with dementia that can affect their everyday coping. This study had a qualitative design with data collection through individual interviews with persons with dementia.

Participants and Recruitment

Informants were recruited by dementia coordinators in three Norwegian municipalities; 12 individual interviews were conducted with persons with dementia. Of these, three were women and nine were men, 62–86 years old, who met the inclusion criteria of living at home, having an early or moderate stage of dementia disease, a diagnosis of dementia and the capacity to provide consent. One informant was not found to meet the inclusion criteria of being in an early to moderate phase of the disease and the interview was removed from the data material.

Data Collection

An interview guide was developed and used to support the interviews.27 All interviews were conducted using short, simple questions, sometimes with follow-up questions.28 The informants were asked to talk about their daily life, what information they needed about the disease, their activities, help and support from others, and what they considered important for them to have a meaningful day. The interviews started with an initial short talk about their life. Data collection was conducted in the informants’ homes or in room at a day care center familiar to them. Three informants had a spouse present. One was there as a support and two were more-active participants. The interviews lasted 45–90 minutes, were recorded, and then transcribed into text.

Analyses

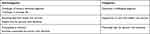

The interview texts were analyzed by qualitative content analysis.29 The analysis began by reading through the entire text to get an overall impression. The text was then read for relevant content for the study, and relevant meaning units were highlighted, then condensed and coded. A review of the condensed and coded meaning units showed that some units had similarities with other units. This provided the basis for sorting into sub-categories; furthermore, some sub-categories had similarities to others and were also grouped into categories. Some meaning units were related to several sub-categories. These were re-evaluated and discussed before they were placed in one category to keep the categories mutually exclusive. Two of the authors started the analysis by reading the text, marking meaning units, condensing and coding. All authors participated in further analysis, working with sorting into sub-categories and, further, into categories, see Table 1. Through discussion, names of sub-categories and categories were developed and agreed upon, see Table 2. Throughout the manifest analysis, three categories and six sub-categories emerged.

|

Table 1 Example from the Analysis Process |

|

Table 2 Sub-Categories and Categories |

Ethical Considerations

The research was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki30 and was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (Project number 58922). The informants’ participation was voluntary and based on informed consent. Verbal and written information about the project and what it would mean to participate was provided to patients by health care workers and researchers to ensure informed voluntary participation. Then, informants gave their written consent.

Findings

Through analysis, we identified three categories that affected coping in everyday life for persons with dementia: Dementia: a challenging diagnosis, Experiences of care from health care services, and Meaningful days for persons with dementia.

Dementia: A Challenging Diagnosis

Some of the participants lived in towns, while others lived in rural areas far away from the activities offered. The informants’ financial situations and, thus, their access to activities requiring a fee, also varied. Common to all of them was that they had a diagnosis that was challenging to live with.

Challenges of Having a Dementia Diagnosis

There were some negative experiences with the diagnosis process. One informant said he felt deceived because no information was provided about the testing used to diagnose dementia or why he had to be tested. When they received the dementia diagnosis, the informants described being given insufficient information about the progression of the disease and what it would meant for everyday life.

Several informants perceived that a dementia diagnosis was a threat to their dignity as a human being. The diagnosis resulted in being stigmatized or looked down on by others:

And there’s a bit of that, too, in getting a diagnosis … because then you … you feel you become like a second-class person.

Gradually, some of them in a way accepted their dementia diagnosis:

Accepted it, just as I have it now. It’s that simple, but you know that you sometimes get such problems with nerves …

They wanted to learn more about their condition; as one put it: “[I] have read a little … got information at a meeting for senior citizens.” None of the informants talked about information from health care workers.

Challenges in Everyday Life

The informants talked about how they experienced the disease. One of the main challenges was forgetfulness; remembering names and recognizing people was a problem, as well as not remembering what to do. One informant shared: “Yes, I forget, or I remember I SHOULD do something, but WHEN? Then it stops, then it becomes a bit … dark.” Regarding routine tasks and things they had learned early in life. “It sits there”, as one said. However, newer tasks—like how to operate household appliances—were harder to remember:

For example, finding out things—like having to press the buttons (on the washing machine) to get what you want … You don’t even remember the procedures …

They discussed forgetting events of daily life: “If we have dinner early in the day, I will not remember it at night.” They talked about their relatives and the strain their diagnosis put on them: “Yes, and it grieves her (his wife) that I must be told, so we struggle a bit with that.”

How information was given in conversations was critical:

[It is] important that you get specific messages then, and that the messages are related to me in a way. Otherwise, it passes me by. So, I’ve noticed that … collective information can be difficult to take in.

Some of the informants talked about difficulties orienting themselves. One of the men talked about a time he had been on a city tour:

Then I was going home and I started wondering … where … which way does the bus go … does it go that way or that way? … But then, like, when it was wild chaos, when does the bus come?

Several informants talked about being tired; they were tired during the day, and they had trouble sleeping at night, which could cause difficulties in their daily lives. They felt that their focus in conversations was reduced, and they pointed out that it is important to use clear communication. One informant said “I disconnected myself then, because it went so fast …. Communication went so fast that I had just tuned it out.”

Social contact was important for everyone but in different forms. Some informants still had good contact with their previous networks, while others experienced being left on their own and wanted someone to talk to:

I think it is great when somebody visits me …. She, the woman I’ve had now, has been so talkative. And it’s great, but it’s only once a month.

Many of the informants talked about daily life with transportation challenges that made it difficult to get out and meet others. For some, transportation was the greatest challenge: “Actually, everything is fine except transportation. That you could get to relatives … ” This led to being more dependent on others.

Living with someone could be beneficial and perceived as a strength. One woman related this wish should she find herself living alone: “I have said many times that I would prefer being at a care center; it would be easier and safer.”

Experiences of Care from Health Care Services

To cope with everyday life, informants had to adapt to life with dementia. Every informant had a general practitioner (GP); some had offers from a home nursing service, and others had experience with respite care in a nursing home. Negative experiences with health care services could add challenges to the dementia diagnosis and make it more difficult to manage everyday life.

Receiving Help from Health Care Services

To gain clarification about the disease, informants had contacted their GPs. However, not everyone was satisfied with the follow-up offers and information:

It was an incredibly long time; it was in the third year. And then it was through an acquaintance who had worked within the system who knew about the various offers …

Others were very satisfied with their GP, who was available when they needed information or to talk. Some explained that they had been offered home nursing care:

We were offered the opportunity to get help for everything, if we needed it. Yet we seem to have managed the jobs ourselves.

For many of the respondents, challenges included reduced vision and hearing as well as various medical diagnoses and comorbidity, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, lung disease, musculoskeletal disorders, and others. Challenges also included incontinence and reduced mobility. Visits from a home nursing care service could bring challenges like uncertainty about a relationship with a caregiver or the feeling that there were too many different caregivers; there could be ten different nurses or other personnel in one week.

Not everyone felt it was as easy as they would like to get help when they asked for it:

If you ask them [home nursing] about something, not everyone notices it … Then, they can’t do this and they can’t do that … It’s not their responsibility.

However, positive experiences were also shared: “I am so pleased with these people down there – how they deal with the old people.”

Respite Care for Persons with Dementia

Respite care can be a way to ensure living in their own home for a longer time. Some of the informants had experienced respite care as a negative experience. One discussed his stay:

It was okay that they put me on respite care because she [his wife] needed time off, but not in such a place. There wasn’t a human being to talk to; it was only 80 to 102-year-olds there.

Another also talked about respite care:

They put me in a ward with patients with dementia needing heavy care. There was a single room with two patients, and the other person in the room needed comprehensive care. … I had to try it, and that was what they could offer, they said. We had to take what they could offer.

Meaningful Days for Persons with Dementia

Informants who participated in activities experienced meaningful days. The activities involved physical and cultural activities, religious gatherings, and socializing with others. Several participants highlighted the importance of individually tailored activities.

Participating in Activities

Activities contributed to meaningful days; informants had something to look forward to, something they experienced as a special occasion in everyday life: “That’s what really saves me, that I’m active. I think this is very important.” In day care, some said they ate breakfast and dinner in addition to participating in the activities:

There is breakfast, then there is exercise, we go for a walk, then dinner and going home. … Sometimes there is a man talking about the old days …. It is interesting. Fourteen days ago, there was a singer …

Although activity was important, some activities could require knowledge about the individual and individualized adaptations by the caregivers. Activities provided the opportunity to meet other persons. An informant discussed the joy of making new friends:

Yes, I like it very well, there are many nice people to be with. You get to know them a little when you are there. These are the same people who are there all the time.

Some had activity-related visiting friends, and they went for walks or visited cafés together.

Some informants would have liked to be offered the opportunity to attend seven days a week; others felt there could be too much. They further revealed that the summer could be challenging due to a lack of such opportunities during the holiday season.

Using a day care center had its costs: “It is expensive for some people to attend a day care center for NOK 200 per day.” This was elaborated on by a relative who participated in the conversation: “When it is paid together with other bills, the pension does not cover NOK 2000 to 3000 per month [for activities].”

To experience meaning, a sense of autonomy was important: “I want freedom now …. I go for long walks, two hours … ” Another said:

It’s this way with Alzheimer’s … even if I have Alzheimer’s I want to do as I want, go to stores and do what I want.

Activities Customized to Person with Dementia

Offers had to be tailored to the individual person:

They tried me on G (day care with physical activities) …, but this was for healthy people. They walked up the mountain tops …. I stayed far behind. They were too vigorous for me …

Several expressed a desire for various types of activities that changed with the progression of the disease. They needed new activities when the old ones became difficult: “[I] Was in a reading circle before but felt left out after a while.”

The daily services could be adapted to different interests. A man interested in cars gladly shared how he could be a guide on car trips. One of the women was interested in needlework and knitting, and she got on well with it. Other informants discussed religious gatherings, such as attending the local church or joining a Christian choir.

Various cultural activities were also of interest:

I have always loved it [music], but now I am more addicted to it, since there is so much I cannot do and do not understand. Then I put on music and I understand that.

Furthermore, others said: “ … thrives on a music café … ” or “ … then I put on video [YouTube] … it’s nice.” Participating in various activities made everyday life meaningful.

Discussion

The study aimed to gain insight into factors that influence everyday coping as described by persons with early/moderate stage of dementia. The main findings show that coping with everyday life could be influenced by the experience of the diagnostic process and information about the dementia disease. It could also be affected by the stigmatization of persons with dementia, as well as by challenges in everyday life such as forgetfulness. In addition, challenges in receiving help could include poor continuity of services, health care staff with limited competence and sometimes a lack of individualized care. On the other hand, when care was person-centered, this led to positive experiences supporting everyday coping. Most of the respondents wanted to participate in day care several days a week, but for some, there were financial constraints. Other positive experiences were having new friends and meaningful activities.

Dementia Diagnosis – Second Class People?

Knowing they would not recover from dementia was difficult for the informants. Accepting the symptoms of dementia is needed,9 but in our study without assistance from professionals. The participants described experiences where they felt that they were considered second-class people after receiving the diagnosis. How persons with dementia are given the diagnosis may send a message about their social status.6 Low et al found that persons with dementia struggled with self-identity and feelings of social stigma. A sub-theme related to stigma is negative stereotypes internalized and related to self-adjustment.31 According to Kitwood,25 the focus should be on being a person with experiences rather than an analytical consideration of the person. However, self-esteem is a perception of one’s worthiness and self-respect and a perception that others find the person worthy and respectable.32

Dementia threatens identity and sense of worth.9 Some of the participants expressed a loss of dignity because of others’ attitudes. According to Wogn-Henriksen, persons with dementia are able to express considerable insight and understanding of their illness and situation.5 Dementia must be understood as a condition that is possible to live with and not just a course of the disease.33 To achieve this, a change of attitude is needed in society and in population.

In line with Bjørkløf et al,9 this study found that memory loss was a challenge for our informants. A decline in personal dignity has generally been caused by cognitive impairments, resulting in diminished autonomy and changes to the individual’s former identity.34 Persons with dementia describe themselves as having challenging everyday lives, with experienced losses and continuously striving to maintain dignity and self-respect.5 In our study falling short in situations meeting others resulted in negative feelings and perceptions with a changed perception of identity and poor coping in the company of others. Constructing a sense of self is necessary for mastery24 and can facilitate problem-oriented coping.21 Listening to what persons with dementia value in themselves, their accomplishments in lives, can be helpful in improving their self-esteem and quality of life.35

Health Services – Supportive or Restrictive?

Persons with dementia reported being happy with the practical arrangement of home nursing care visits, even though these visits were mostly brief and task-oriented.11 In this study, when the offer of help met their needs and capacity, they were satisfied. Otherwise, it could cause them to lose confidence in the service. Kitwood saw the need for a change from a task-oriented nursing culture to a new, person-centered value as a basis for dementia care.25 Emotional support is an external coping resource.9 Taking care of “those who forget” has been identified as a comprehensive core value within dignity preservation in dementia.34 Therefore, as shown in our study, there is a need for increased competence among employees which includes knowledge, skills and attitudes. Educational programs for health care workers are described to provide increased knowledge about dementia and treatment; relationship-building is emphasized to provide good care, while continuity and flexibility are cornerstones of care and perceived improvements.36 Being seen is also important in building relationships36,37 and necessary to maintain self-confidence.24

When health care was perceived as positive, persons with dementia felt safer and the help was more predictable, which is a prerequisite for staying focused and mastering life and daily tasks. An open and flexible approach made the providers aware of how their own approach to each care recipient had relevance and affected the person’s home atmosphere. Staying calm is crucial in the provision of care and can help support hope and coping.36

Since adjustment to dementia differs from person to person, professional caregivers need to use a case-specific approach to the provision of care for persons with dementia.38 For persons with dementia, adjustment by changing expectations toward themselves through seeking information being active and making changes to handle the situation are important for coping.9 In this study, information about dementia and making changes to handle the situation was sparse. The care provided must consider not only the person’s limitations but also his or her possibilities for problem-oriented coping.21 For the participants in our study, limitations such as forgetfulness and sensitivity to stimuli were exacerbated by poor staff continuity. According to Berglund et al, continuity and flexibility are cornerstones of good care.36

Our findings indicate that persons with dementia need predictability and security, which can be achieved with permanent staff who have knowledge about them and support their resources. Life storytelling can be helpful when arranging individualized offers of service to preserve the person’s identity and facilitate meaningful days.39 This knowledge should also be used when planning short–time ward stays to provide an opportunity for respite for relatives and a good experience for persons with dementia.

Engaging with Life

The participants in this study talked about positive experiences through engaging with life rather than living explicitly with dementia. The person might transcend the condition and seek ways to maintain his or her identity,7 which is in line with other findings. Important for quality of life is the ability to identify patterns of meaning, and these can be factors related to a social and caring environment.40 Humor and social support are important for coping with rising demands in life with dementia.9 The participants in this study did not talk about humor but about meaningful activities in day care in line with activities that supported identity and sense of self as found by Frazer et al.24

There are various forms of day care.10,12,33,37,41–44 For persons with dementia, positive outcomes of day care are found to be related to meaningful activities that strengthen social connections and to careful staff facilitation which create a positive and welcoming atmosphere. Furthermore, Fæø et al found that persons with dementia had positive views of the day care centers as places that offered them the opportunity to broaden their environment.11 In our study, the activities offered provided pleasure when they were adapted to the individual’s needs, interests, and abilities. Coping is not only a practical everyday function, but also related to psychosocial and existential needs.

The experience of meaning differs from person to person, and a case-specific approach to care is needed.38 According to the present study’s participants, day care with individual facilitation helped satisfy the desire to participate in activities. The main focus was on enjoying the here and now and not worrying too much about the future; other studies have reported similar findings.11 Persons with dementia are not only passive victims of their illness; they also have the ability to adapt and develop new approaches that help to recreate their lives within the new premises set by the disease.5

Loss of social needs and meaningful activities can lead to loneliness.9 For participants in this study, meeting other persons was important. At the day care center, they made new friends with whom they had positive experiences. Studies have found that human relationships are given new meaning but can also be complicated by dementia.5 Having dementia is a link that may connect them, and they feel a sense of confidence with one another.37 In our study it was also pointed out that not all activities were meaningful, but those that were adapted to the individual based on principles of person-centered care seemed to support the sense of self.25 Good relations can be taken care of in different activities, also by contribution from volunteers.20

Positive strategies and coping mechanisms are associated with sense of self, dignity and quality of care.45 Allowing self-determination can also strengthen the ability to manage stress23 through problem-oriented and emotional coping.21 Advocating for the person’s autonomy and integrity involved having compassion for the person and confirming his or her worthiness and sense of self creating a humane and purposeful environment was seen as a primary foundation for dignity-preserving dementia care.34 Nicholson identified shared decision-making; promoting individuality, independence and autonomy; and communication as important experiences for older persons with dementia46 Perhaps it was the experience of autonomy and integrity through the activities that resulted in the good feelings and positive experiences of people with dementia in this study.

Strength and Limitations

The strength of this study was to bring out the voice of persons with dementia and their experiences with possibilities and limitations living with dementia disease.

Recruitment and sample: Some of the participants were diagnosed in the early stage, while others were in the moderate stage of dementia. One consequence of our inclusion criteria was that we did not hear the voices from persons with severe dementia, which could be different from those with mild or moderate dementia. The participants were diagnosed by GP and experts in geriatrics. The recruitment was administrated by dementia coordinators in three municipalities who ensured that the participants had a diagnosis of dementia. Scores in the diagnostic tools were not relevant to the study as health personnel confirmed the dementia diagnosis. The stages of dementia was also not of importance as long as the persons with dementia were able to give informed consent to participate in the study and conduct a conversation about coping in everyday life.

Sample size: The guideline for sample size in qualitative research is not only to study a few sites or individuals but also to collect extensive detail about each site or individual studied. In qualitative study, the intent is not to generalize the information but to elucidate the particular, the specific.47 Qualitative studies focus on relatively small samples selected purposefully. The logic and power of purposeful sampling lie in selecting an information-rich case for study in depth.27

Data collection and analysis: The interviews varied in how comprehensive they were. To avoid over-interpretation of the text-material, the scope for the analysis was on the manifest content, which is the visible, obvious component of what the text said.29

In this study three of the participants were supported by family members. Family members could affect the persons with dementia, which supported them to take part in this study.

Conclusion

To strengthen everyday coping for persons with dementia living at home, there is a need for openness about the disease and the participation of persons with dementia, as well as openness in attitudes toward those with dementia as full-fledged persons. Follow-up for persons with dementia must be carried out by reputable professionals trained and educated in dementia care.

There is a need for respite care driven by principles of person-centered care in familiar and meaningful surroundings connected to their day care center. Finally, the municipalities must have contact people, dementia coordinators, and/-teams available for persons with dementia at the time of diagnosis position and afterwards. There is a need for more knowledge about dementia coordinators, and/-teams in dementia care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contribution from the persons with dementia who shared their thoughts and experiences in the individual interviews. Thanks are also given to the project’s reference group, consisting of clever and positive staff from the USHTs (Centers for Development of Institutional and Home Care Services) for important inputs and comments along the process.

Funding

This study received funding from Regional Research Fund Mid-Norway.

Disclosure

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Dua T, Seeher KM, Sivananthan S, et al. World Health Organization’s global action plan on the public health response to Dementia 2017–2025. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(7):PP1450–P1451. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.758

2. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Meld.St 15 (2017–2018) Leve hele livet. En kvalitetsreform for eldre. (A full life- all your life. A Quality Reform for Older Person). 2018.

3. Olsen C, Pedersen I, Bergland A, et al. Differences in quality of life in home-dwelling persons and nursing home residents with dementia– a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:137. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0312-4

4. Johansson MM, Marcusson J, Wressle E. Cognitive impairment and its consequences in everyday life: experiences of people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia and their relatives. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(6):949–958. doi:10.1017/S1041610215000058

5. Wogn-Henriksen K. Du Må … Skape Deg Et Liv”: En Kvalitativ Studie Om Å Oppleve Og Leve Med Demens Basert På Intervjuer Med En Gruppe Personer Med Tidlig Debuterende Alzheimers Sykdom. Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet, Fakultet for Samfunnsvitenskap Og Teknologiledelse Psykologisk Institutt. Phd. Trondheim: Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet, Fakultet for samfunnsvitenskap og teknologiledelse, Psykologisk institutt; 2012.

6. Low L-F, McGrath M, Swaffer K, et al. Communicating a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic mixed studies review of attitudes and practices of health practitioners. Dementia. 2019;18(7–8):2856–2905. doi:10.1177/1471301218761911

7. Wolverson EL, Clarke C, Moniz-Cook ED. Living positively with dementia: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:676–699. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1052777

8. Cotter VT, Gonzalez EW, Fisher K, et al. Influence of hope, social support, and self-esteem in early stage dementia. Dementia. 2018;17(2):214–224. doi:10.1177/1471301217741744

9. Bjørkløf GH, Helvik A-S, Ibsen TL, et al. Balancing the struggle to live with dementia: a systematic meta-synthesis of coping. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):295. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1306-9

10. Tretteteig S, Vatne S, Rokstad AMM. Meaning in family caregiving for people with dementia: a narrative study about relationships, values, and motivation, and how day care influences these factors. (ORIGINAL RESEARCH)(Report). J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:445. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S151507

11. Fæø SE, Bruvik FK, Tranvåg O, et al. Home-dwelling persons with dementia’s perception on care support: qualitative study. Nurs Ethics. 2020;969733019893098.

12. Myren G-E, Enmarker I, Hellzen O, et al. The influence of place on everyday life: observations of persons with dementia in regular day care and at the green care farm. Health 2017;9(2):261–278.

13. Ministry of Health and Care Services. Dementia Plan 2020. 2016.

14. Eriksen S, Pedersen I, Taranrod LB, et al. Farm-based day care services–a prospective study protocol on health benefits for people with dementia and next of kin. (STUDY PROTOCOL)(Report). J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:643. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S212671

15. Jarrott SE, Bruno K. Intergenerational activities involving persons with dementia: an observational assessment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2003;18(1):31–37. doi:10.1177/153331750301800109

16. Ekra EM, Dale BR. Systematic use of song and music in dementia care: health care providers’ experiences. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:143–151. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S231440

17. Gibson G, Dickinson C, Brittain K, et al. The everyday use of assistive technology by people with dementia and their family carers: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0091-3

18. Hedman A, Lindqvist E, NygArd L. How older adults with mild cognitive impairment relate to technology as part of present and future everyday life: a qualitative study. (Report). BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:73. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0245-y

19. Megges H, Freiesleben SD, Rösch C, et al. User experience and clinical effectiveness with two wearable global positioning system devices in home dementia care. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;4(1):636–644.

20. Malmedal WK, Steinsheim G, Nordtug B, et al. How volunteers contribute to persons with dementia coping in everyday life. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:309–319. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S241246

21. Folkman S, Lazarus R. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21:219–239. doi:10.2307/2136617

22. Bjørkløf GH, Engedal K, Selbæk G, et al. Coping and depression in old age: a literature review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35(3–4):121–154. doi:10.1159/000346633

23. Sharp BK. Stress as experienced by people with dementia: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Dementia. 2019;18(4):1427–1445. doi:10.1177/1471301217713877

24. Frazer SM, Oyebode JR, Cleary A. How older women who live alone with dementia make sense of their experiences: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Dementia. 2012;11(5):677–693. doi:10.1177/1471301211419018

25. Kitwood T. En Revurdering Af Demens - Personen Kommer I Første Rekke. Fredrikshavn: Dafolo Forlag; 1999.

26. Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, et al. Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: the INTERDEM manifesto. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(3):283–290. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.543665

27. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods.

28. Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Anderssen TM, et al. Det Kvalitative Forskningsintervju. 3. Utg. Ed. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk; 2015.

29. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

30. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053

31. Low L-F, Swaffer K, McGrath M, et al. Do people with early stage dementia experience prescribed disengagement®? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(6):807–831. doi:10.1017/S1041610217001545

32. Mruk CJ. Self-Esteem Research, Theory, and Practice Toward a Positive Psychology of Self-Esteem. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

33. Rokstad AMM, McCabe L, Robertson JM, et al. Day care for people with dementia: a qualitative study comparing experiences from Norway and Scotland. Dementia. 2019;18(4):1393–1409. doi:10.1177/1471301217712796

34. Tranvåg O, Petersen KA, Nåden D. Dignity-preserving dementia care: a metasynthesis. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20(8):861–880. doi:10.1177/0969733013485110

35. Nordtug B, Torvik K, Brataas HV, et al. Former work life and people with dementia. Adv Nurs Sci. 2018;41(1):70–83. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000191

36. Berglund M, Gillsjö C, Svanström R. Keys to person-centred care to persons living with dementia– experiences from an educational program in Sweden. Dementia. 2019;18(7–8):2695–2709. doi:10.1177/1471301218754454

37. Söderhamn U, Aasgaard L, Landmark B. Attending an activity center: positive experiences of a group of home-dwelling persons with early stage dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;2014(9):1923–1931. doi:10.2147/CIA.S73615

38. Holst G, Hallberg IR. Exploring the meaning of everyday life, for those suffering from dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2003;18(6):359–365. doi:10.1177/153331750301800605

39. Gridley K, Birks YF, Parker GM. Exploring good practice in life story work with people with dementia: the findings of a qualitative study looking at the multiple views of stakeholders. Dementia. 2020;19(2):182–194. doi:10.1177/1471301218768921

40. Holopainen A, Siltanen H, Pohjanvuori A, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of people with dementia and with quality of life-improving interventions: scoping review. Dementia. 2019;18(4):1507–1537. doi:10.1177/1471301217716725

41. Humphrey J, Montemuro M, Coker E, et al. Artful moments: a framework for successful engagement in an arts-based programme for persons in the middle to late stages of dementia. Dementia. 2019;18(6):2340–2360. doi:10.1177/1471301217744025

42. Ridder HMO, Stige B, Qvale LG, et al. Individual music therapy for agitation in dementia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(6):667–678. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.790926

43. Skinner MW, Herron RV, Bar RJ, et al. Improving social inclusion for people with dementia and carers through sharing dance: a qualitative sequential continuum of care pilot study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e026912. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026912

44. Woodbridge R, Sullivan MP, Harding E, et al. Use of the physical environment to support everyday activities for people with dementia: a systematic review. Dementia. 2018;17(5):533–572. doi:10.1177/1471301216648670

45. Bosco A, Schneider J, Coleston-Shields DM, et al. Dementia care model: promoting personhood through co-production. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;81:59–73. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.003

46. Nicholson L. Person-centred care: experiences of older people with dementia. Nurs Standard. 2017;32,8,:41–51. doi:10.7748/ns.2017.e10558

47. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2018.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.