Back to Journals » Orthopedic Research and Reviews » Volume 11

Conversion to total hip arthroplasty in posttraumatic arthritis: short-term clinical outcomes

Authors Taheriazam A, Saeidinia A

Received 22 August 2018

Accepted for publication 6 December 2018

Published 4 February 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 41—46

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/ORR.S184590

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Clark Hung

Afshin Taheriazam,1 Amin Saeidinia2,3

1Department of Orthopedics Surgery, Tehran Medical Sciences Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran; 2Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran; 3Medical Faculty, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Background: Fractures of the acetabulum are challenging and very difficult to treat, and even after fixation, they can lead to posttraumatic arthritis. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been the most common surgery performed for the complications of posttraumatic arthritis in this group of patients.

Aim: In this article, it is aimed to assess the functional results and complications of the conversion to THA for posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular fracture.

Patients and methods: Forty-nine patients were followed up for a mean of 3.7 years (range 2–5 years). The complications included four cases of sciatic nerve palsy, all of which had injury during the first operation. Two cases underwent two-stage surgery because of infection which was demonstrated by a high level of erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein and according to frozen section samples, which were sent intraoperatively with >10 neutrophil/high-power field; one case was then managed by a one-stage protocol for infection after THA was infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. In 1 case, we used the Girdlestone operation for severe infections and uncontrolled diabetes; in 2 cases, we used cages; and in 47 cases, we used uncemented cups.

Results: The mean of modified Hip Harris Score improved from 47 (31–66) before the conversion to 89 (79–95) at the final follow-up. The pain component of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities also increased from an average of 15 (7–20) to 4 (0–11) at the final follow-up. No dislocation, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary thromboembolism, new nerve injury, and heterotopic ossification occurred.

Conclusion: The conversion to THA after posttraumatic arthritis in acetabular fracture can lead to reasonable pain relief and functional improvement.

Keywords: acetabular fracture, conversion total hip arthroplasty, posttraumatic arthritis, internal fixation

Introduction

Complex acetabular fracture has not been clearly explored in the literature. Its utility was limited to associated fracture patterns based on the Letournel classification by some authors. However, others have used it for various types of fractures, including processions of the acetabulum. Patterns like this are more demanding in management and utilization.1 Acetabular fractures are challenging and difficult to manage. They can result in posttraumatic arthritis, avascular necrosis of femoral head, or both. Despite the fact that open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) reduces the risk of posttraumatic arthritis, the risk cannot be completely eliminated.2 Furthermore, ORIF failure in fracture of acetabulum ranges between 12% and 57% in different investigations.3–6 In case of posttraumatic arthritis and its adverse effects, total hip arthroplasty (THA) might be a feasible resolving procedure.7 The conversion of acetabular fracture to arthroplasty leads to different survival rates. Regarding the frequency of acetabular fracture in the elderly, it can be predicted that number of patients in this age group undergoing THA will increase.1,3,4,8–10

Post-acetabular fracture THA poses different challenges for orthopedic surgeons, including residual pelvis deformities, bone loss in the acetabulum, infections, osteonecrosis, heterotopic ossification, maintained metalwork, sciatic nerve palsy, and other problems encountered in acetabular element fixations in the long term.8 Indication for performing an acute THA in young people with concurrent femoral head and acetabular difficulties is severe nonreconstructable comminution, and in geriatric patients, the indication is severe bony comminution. Outcomes of THA for posttraumatic acetabular fracture consist of good pain relief and functional developments.10,11 In a large-scale population meta-analysis, 3,670 acetabular fractures were included and the most common long-term postsurgical ORIF complication was posttraumatic arthritis (20%). The rate of osteonecrosis of femoral head was 5.6%.12 In other investigations, the incidence of posttraumatic arthritis was between 10% and 60% in some series. The incidence of femoral head osteonecrosis was between 3% and 53%.13 In one study, the incidence of conversion of ORIF to THA during and after 5 years of first treatment was 11%.14 Fractures of acetabulum might grow the risk of posttraumatic degenerative arthritis and THA. Previous investigations revealed that adverse events related to conversion of ORIF to THA are higher in comparison with primary THA.15 Predisposing factors in conversion arthroplasty failure are comminution and initial displacement, femoral head defect, fracture of femoral head or neck, and crush in anterolateral or posterior portion of acetabulum. It is suggested to perform THA immediately when patients encounter these situations after ORIF.16,17

The problems associated with performing converted THA in such patients are poor bone supply, damaged tissue, higher risk of infection, and presence of previous implant.8 In the current study, the researchers assessed short-term functional outcomes and the associated complications in posttraumatic arthritis patients who had undergone THA after ORIF.

Patients and methods

This was an observational prospective analysis of the outcomes of patients who were candidates for conversion of posttraumatic arthritis to THA at Erfan and Milad hospitals, Tehran, Iran. There were 43 males and 6 females, ranging in age from 17 to 68 years at the time of injury. All patients had been operated on for the conversion of posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular fracture internal fixation to THA, between 1998 and 2015. It is important to mention that all factors related to the failure of fixation after posttraumatic arthritis often make the conversion of THA necessary. All the patients who were candidates for a conversion surgery were investigated according to a standard protocol of 3.2–17.1 years (average 6.2 years). All cases had posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular fracture and needed THA because of severe pain, limitation of movement, and stiffness.

All surgeries were done by a direct lateral (Hardinge) approach using a standard-length incision with the patient in the lateral position, and every effort was made to obtain a safe and certain distance from the previous incision. Patients were operated under general anesthesia, and according to a standard technique with minor variations, they underwent surgery. The skin and subcutaneous tissues were incised in one line, and the plane was established between the subcutaneous tissues and the gluteal fascia at 1–2 cm on both sides. Gluteus medius and minimus splitting was done and capsulotomy was subsequently performed. During THA, the plates were not removed and only the screws in the joints or on the reamer path were taken out or removed by a milling tool. This was not the initial surgery and afterward, the complications of posttraumatic arthritis occurred. Therefore, it is undeniable to have sufficient accuracy in reaming the acetabulum and taking press-fit from the cup. The researchers removed acetabular implants if they were impacted, becoming loose, or there was suspicion of infection in them. For some cases, osteotomy was performed for removing the plates. All other processes during the patient evaluation were performed according to the available protocols.18

In 1 case, the researchers used the Girdlestone operation for severe infections and uncontrolled diabetes; in 2 cases, cages were used; and in 47 cases, uncemented cups were used. The bearing surface was metal on highly cross-linked polyethylene, except in five young cases in which the senior author used third-generation delta ceramic with highly cross-linked polyethylene. It is worth mentioning that in all patients, X-ray was performed during the operation and once the operation was complete, an abduction pillow was used between the legs. Moreover, prophylactic antibiotics were started 30 minutes before the incision at the operating room and repeated for two other doses. In order to decrease bleeding during the operation, 15 mg/kg of intravenous tranexamic acid was used and all patients underwent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis for 1 month by enoxaparin, and for heterotopic ossification, indomethacin-SR 75 mg was given daily for 6 weeks.18

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistical analyses were applied to present mean ± SD of quantitative variables. Paired t-test was used to compare before and after operation variables, and linear regression test for evaluation of outcomes. For all analyses, SPSS software was used (SPSS 19.0 for Windows; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics statement

All ethical issues for patients’ information and procedures were observed according to the ethical committee of Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tehran branch, and ethical statements were approved by the ethical committee. All patients were asked to complete a written informed consent for participation in this study, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Clinical and radiographic assessment was performed after the conversion procedure for all participants. The modified Hip Harris Score (MHHS) was recorded before the operation, 6 months after the operation, and at the final follow-up of 2 years. In the current study, no dislocation, DVT or pulmonary thromboembolism, new nerve injury (only in 4 cases of preoperative sciatic nerve injury, tendon transfer was done 6 months postoperatively), or heterotopic ossification occurred in any of the patients. Reoperation was done in two cases; in one case, it was because of an acute infection treated by a one-stage revision and in the other case, it was because of severe infection and sepsis, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and also the age of patient, which was managed by Girdlestone.

Radiographic evaluation

All cases underwent THA due to posttraumatic arthritis for an average of 6.2 years (between 3.2 and 17.1 years) after internal fixation. Typically, the two types of fractures that can be witnessed in acetabular fracture are simple and complex fractures. Most patients had complex fractures and were all first treated by plates. From 3 to 17 years after the initial treatments, all of them had posttraumatic arthritis after ORIF and needed THA due to complications associated with pervious operation for their fracture of acetabula.

Complications

The complications included four cases of sciatic nerve palsy, all of which had injury during the first operation. Two cases underwent two-stage surgery because of infection which was demonstrated by a high level of erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein and according to frozen section samples (confirmed by >10 polymorphonuclear cell/high-power field); one patient was infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after THA, who was then managed by a one-stage protocol for infection.

Postoperative follow-up

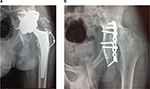

Even though the MHHS at the final follow-up of 2 years was documented for all patients, 6 months later, the MHHS was applied to evaluate the results of the conversion procedure with regard to pain alleviation and practical development. Based on the outcomes, the MHHS was improved from 47 (31–66) before the operation to 89 (79–95) at 6 months after THA. In addition, the pain component of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities was improved from an average of 15 (7–20) to 4 (0–11) at the final follow-up. Figures 1–4 demonstrate four cases of the current study which were treated; 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A present preoperative figures, and 1B, 2B, 3B, and 4B indicate the last follow-up figures.

Discussion

As the age of the population is growing, fracture of the proximal side of femur is becoming more frequent.19 Furthermore, THA is one of the best procedures in today’s orthopedic surgeries, which is the main favorable process in orthopedics. It is done for different indications and its indications for posttraumatic arthritis are similar to those for any patient with destructed hip disorder, such as uncontrollable pain, difficulty in daily activities, validated radiological signs attributed to advanced arthritis, articular incongruity, or osteonecrosis.18

Most acetabulum fractures, either simple or complex, are managed by the ORIF method. In order to obtain the results, orthopedic surgeons perform THA when patients have posttraumatic arthritis-related complications. The critical key point is an accurate preoperation, which will improve the success rate of a surgery. On the other hand, performing a surgery in a correct and standard manner is also necessitated: standard intraoperative conversion landmarks, which include the location of the pubis, teardrop, ilium, and ischium after vast release and elimination of all debris and plates that directly affect the acetabular placement.20–22

After failed internal fixation, THA of acetabular fractures was the main stem of different studies. Hammad et al23 assessed 32 patients undergoing THA after failed dynamic hip screw fixation and found only one periprosthetic fracture and one dislocation. Clinical outcomes were good–excellent in 78% of patients at the final follow-up.23 By increasing the age of the population, the rate of osteoporotic fractures, such as those of pelvis and acetabulum, will be increased. Management of elderly patients with an acetabular fracture is more controversial than that of younger case with the same injuries, where prevention of posttraumatic arthritis and THA remains the best to limit the necessity for revision arthroplasty. Arthroplasty for fractures of the proximal femur is commonplace in the older population and is a mainstay of the treatment for promoting early mobilization and weight bearing. Nevertheless, in performing acute THA for elder acetabular fracture, the majority of surgeons do not allow for prompt weight bearing after surgery. Therefore, the argument about the best treatment of these challenging fractures still persists. In total, four treatment options have emerged, including non-surgical treatment with early mobilization, ORIF, limited open reduction and percutaneous screw fixation, and acute THA. Nonetheless, the exact indications and benefits of each treatment still remain unknown. The clinical outcomes have been greatly improved with the advancement of implant designs and cementless fixation, particularly on the acetabular side.24,25 There were some limitations in the current investigation. The study did not include a narrow age group for analysis and the sample size was small during the period of the study, which can affect the results’ generalizability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, findings of the present research suggest that the conversion of posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular internal fixation to THA is clinically successful without increased risk of complications, and is a safe option that provides good functional results, with marginally higher rates of intraoperative complications. However, the patients should definitely be warned of the possibility of incomplete relief of groin pain postoperatively. It can be expected that the patients would be more satisfied and have less pain with appropriate preoperative planning, and awareness about the common complications could improve the outcomes. It is suggested to perform a large-scale investigation with subgroups of different ages to increase the validity and generalizability of results.

Data sharing statement

The data sets utilized or analyzed in this study are accessible from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all nurses and personnel of Erfan and Milad hospitals in Tehran, Iran for their cooperation in all stages of the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

El-Khadrawe TA, Hammad AS, Hassaan AE, El-Khadrawe TA, Hammad AS, Hassaan AE. Indicators of outcome after internal fixation of complex acetabular fractures. Alexandria Med J. 2012;48(2):99–107. | ||

Yu L, Zhang CH, Guo T, Ding H, Zhao JN. [Middle and long-term results of total hip arthroplasties for secondary post-traumatic arthritis and femoral head necrosis after acetabular fractures]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2016;29(2):109–113. Chinese. | ||

Diwanji SR, Kim SK, Seon JK, Park SJ, Yoon TR. Clinical results of conversion total hip arthroplasty after failed bipolar hemiarthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):1009–1015. | ||

Sierra RJ, Mabry TM, Sems SA, Berry DJ. Acetabular fractures: the role of total hip replacement. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(11 Suppl A):11–16. | ||

Berry DJ, Halasy M. Uncemented acetabular components for arthritis after acetabular fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:164–167. | ||

Srivastav S, Mittal V, Agarwal S. Total hip arthroplasty following failed fixation of proximal hip fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2008;42(3):279. | ||

Pang QJ, Yu X, Chen XJ, Yin ZC, He GZ, The management of acetabular malunion with traumatic arthritis by total hip arthroplasty. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(1):191. | ||

Winemaker M, Gamble P, Petruccelli D, Kaspar S, de Beer J. Short-term outcomes of total hip arthroplasty after complications of open reduction internal fixation for hip fracture. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):682–688. | ||

Taheriazam A, Saeidinia A, Keihanian F. Total hip arthroplasty and cardiovascular complications: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:685–690. | ||

Taheriazam A, Saeidinia A. Cementless one-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty in osteoarthritis patients: functional outcomes and complications. Orthop Rev. 2017;9(2):6897. | ||

Taheriazam A, Saeidinia A. Conversion of failed hemiarthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty: a short-term follow-up study. Medicine. 2017;96(40):e8235. | ||

Giannoudis PV, Grotz MR, Papakostidis C, Dinopoulos H. Operative treatment of displaced fractures of the acetabulum. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):2–9. | ||

Swanson MA, Huo MH. Total hip arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthritis after previous acetabular fractures. Semin Arthroplasty. 2008;19(4):303–306. | ||

Mears DC, Velyvis JH, Chang CP. Displaced acetabular fractures managed operatively: indicators of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:173–186. | ||

Ranawat A, Zelken J, Helfet D, Buly R. Total hip arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular fracture. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(5):759–767. | ||

Amstutz HC, Smith RK. Total hip replacement following failed femoral hemiarthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(8):1161–1166. | ||

Schnaser E, Scarcella NR, Vallier HA. Acetabular fractures converted to total hip arthroplasties in the elderly: how does function compare to primary total hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(12):694–699. | ||

Krause PC, Braud JL, Whatley JM. Total hip arthroplasty after previous fracture surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(2):193–213. | ||

Archibeck MJ, Carothers JT, Tripuraneni KR, White RE. Total hip arthroplasty after failed internal fixation of proximal femoral fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):168–171. | ||

Haidukewych GJ, Berry DJ. Salvage of failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;412:184–188. | ||

Mortazavi SM, R Greenky M, Bican O, Kane P, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ. Total hip arthroplasty after prior surgical treatment of hip fracture is it always challenging? J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(1):31–36. | ||

Zhang L, Zhou Y, Li Y, Xu H, Guo X, Zhou Y. Total hip arthroplasty for failed treatment of acetabular fractures: a 5-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1189–1193. | ||

Hammad A, Abdel-Aal A, Said HG, Bakr H. Total hip arthroplasty following failure of dynamic hip screw fixation of fractures of the proximal femur. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(6):788. | ||

Romness DW, Lewallen DG. Total hip arthroplasty after fracture of the acetabulum. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72(5):761–764. | ||

Makridis KG, Obakponovwe O, Bobak P, Giannoudis PV. Total hip arthroplasty after acetabular fracture: incidence of complications, reoperation rates and functional outcomes: evidence today. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(10):1983–1990. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.