Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 10 » Issue 1

Continuing to Confront COPD International Surveys: comparison of patient and physician perceptions about COPD risk and management

Authors Menezes A , Landis S, Han M, Muellerova H , Aisanov Z , van der Molen T, Oh YM , Ichinose M, Mannino D , Davis K, Hollingworth K

Received 15 September 2014

Accepted for publication 4 November 2014

Published 20 January 2015 Volume 2015:10(1) Pages 159—172

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S74315

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Ana M Menezes,1 Sarah H Landis,2 MeiLan K Han,3 Hana Muellerova,2 Zaurbek Aisanov,4 Thys van der Molen,5 Yeon-Mok Oh,6 Masakazu Ichinose,7 David M Mannino,8 Kourtney J Davis9

1Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil; 2Worldwide Epidemiology, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK; 3Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 4Pulmonology Research Institute, Moscow, Russia; 5University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; 6University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea; 7Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan; 8University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY, USA; 9Worldwide Epidemiology, GlaxoSmithKline, Wavre, Belgium

Purpose: Using data from the Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician and Patient Surveys, this paper describes physicians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) prognosis, and compares physician and patient perceptions with respect to COPD.

Methods: In 12 countries worldwide, 4,343 patients with COPD were identified through systematic screening of population samples, and 1,307 physicians who regularly saw patients with COPD were sampled from in-country professional databases. Both patients and physicians completed surveys about their COPD knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions; physicians answered further questions about diagnostic methods and treatment choices for COPD.

Results: Most physicians (79%) responded that the long-term health outlook for patients with COPD has improved over the past decade, largely attributed to the introduction of better medications. However, patient access to medication remains an issue in many countries, and some physicians (39%) and patients (46%) agreed/strongly agreed with the statement “there are no truly effective treatments for COPD”. There was strong concordance between physicians and patients regarding COPD management practices, including the use of spirometry (86% of physicians and 76% of patients reporting they used/had undergone a spirometry test) and smoking cessation counseling (76% of physicians reported they counseled their smoking patients at every clinic visit, and 71% of smoking patients stated that they had received counseling in the past year). However, the groups differed in their perception about the role of smoking in COPD, with 78% of physicians versus 38% of patients strongly agreeing with the statement “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD”.

Conclusion: The Continuing to Confront COPD International Surveys demonstrate that while physicians and patients largely agreed about COPD management practices and the need for more effective treatments for COPD, a gap exists about the causal role of smoking in COPD.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, physician survey, patient survey, beliefs, perceptions

Introduction

Although chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable disease,1 it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, giving rise to an enormous social and economic burden.1,2 In 2010, COPD was ranked as the third leading cause of mortality and the ninth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost worldwide.2,3

The evidence-based guidelines available to aid physicians in the management and treatment of patients are frequently not fully implemented in clinical practice, as demonstrated across many regions worldwide.4–11 Reasons for this include a lack of familiarity with guidelines and a lack of confidence in implementation and access/time constraints,9–11 but have also been shown to be associated with physician perceptions and beliefs about COPD management. Yawn et al10 reported that among 278 primary care physicians (PCPs) and practice nurses/assistants, only 15% thought COPD treatments were very or somewhat useful and 3% thought pulmonary rehabilitation was useful or very useful, despite its availability to 32% of those sampled. In a Swiss study of 455 PCPs, 52% stated that they were uncomfortable with smoking cessation counseling, 72% underused pulmonary rehabilitation programs, and the indications and effects of COPD treatments were poorly recognized.7

Few studies have investigated the perceptions and beliefs about COPD from both a physician and a patient perspective. Hernandez et al12surveyed 58 respiratory specialists and 640 patients with COPD and reported that perceived knowledge needs and preferred methods of education differed between physicians and patients. For example, physicians identified smoking cessation counseling as an educational priority, while patients wanted to be informed more about their disease progression.

The Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey aimed to describe COPD disease burden and perceptions about the disease from both the patient and physician perspectives across 12 countries. This paper describes physicians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding COPD prognosis and treatment, and how physician and patient perceptions compare with respect to multiple aspects of COPD.

Methods

A detailed description of the study design, methodology, and response rates for the Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician and Patient Surveys have been reported previously.13,14 Briefly, both surveys were conducted during 2012–2013 in Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, South Korea, Spain, the UK, and the USA.

The Physician Survey sampled PCPs and respiratory specialists who regularly saw patients with COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis (contact with ≥5 patients per month, on average) from in-country databases of professional associations to achieve an a priori 3:1 ratio of PCP to respiratory specialists in each country.13 In total, 1,307 physicians (74% PCPs, 26% respiratory specialists) agreed to participate. A single survey covering knowledge and behavior around diagnosis and treatment of COPD and beliefs about COPD risk and prognosis was translated into local language, and interviews were conducted online, by telephone, or face-to-face. The response rate by country ranged from 10% (USA) to 38% (Spain).

The Patient Survey was primarily designed to estimate the prevalence of COPD in each country, and therefore, patients with COPD were identified systematically by screening probability samples of households followed by telephone or face-to-face interviews of eligible patients. A single survey that incorporated questions about patients’ perception of their disease severity and its impact on daily living, and validated patient-reported outcome instruments to assess disease severity, medication adherence, and patient engagement was translated into local language.14 Eligible patients were adults aged 40 years and older who reported either 1) a physician diagnosis of COPD/emphysema or 2) a physician diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, or 3) met a symptom-based definition of chronic bronchitis and either were taking respiratory medication for their condition or had chronic cough with phlegm most days. The Patient Survey identified 106,876 households with at least one person aged ≥40 years, of which 4,343 respondents fulfilled the earlier-mentioned case definition of COPD and completed the full survey. Response rates for the Patient Survey ranged from 25% (UK) to 74% (Brazil).

To elicit physician and patient perceptions regarding COPD, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with a series of statements using a 4-point scale (strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree). The statements were not designed to have a “correct” answer, but rather to evaluate respondent perception. Most statements were based on the original Confronting COPD International Survey or other published surveys to allow for comparison across time points and different study populations.15–17

As the Patient Survey sample was identified from screening general population probability samples, we were able to weight the results included herein by age and sex according to the latest census data available in each country to obtain representative countrywide estimates. The Physician Survey results are not weighted as standardized reliable estimates of the universe of physicians in each country are not readily available for all countries.

The comparison between physician and patient perceptions on topics addressed in both surveys are qualitative in nature, as we did not have an a priori hypothesis about the expected concordance nor were we able to conduct statistical testing due to slight differences in the wording of questions between surveys.

Results

Demographics

The demographic characteristics of the physician and patient samples have been described in detail elsewhere.13,14 Among the total physician sample, 75% were male, 81% practiced in an outpatient setting, and 54% worked in a multispecialty practice, with the majority of practices found in small cities/towns (50%) or in central cities (42%). Approximately half had graduated from medical school later than 1990.

Patient respondents had a mean age of 61 years; 48% were male, with a mean body mass index of 26.9 (standard deviation, 6.5) kg/m2. Smoking status was reported as 36% nonsmokers, 37% former smokers, and 28% current smokers. Most commonly reported comorbidities were hypertension (45%) and asthma (42%).

Physician beliefs about COPD prognosis and treatment

The majority of physicians surveyed (79%) reported that they believe the long-term health outlook for patients with COPD has improved compared to 10 years ago, and this view was generally consistent across countries (range, 55%–94%; Table S1). The most common reasons given for the improved outlook were “better medications for COPD” (86%; range, 75%–90%) and “increased smoking cessation/less passive smoking” (28%; range, 15%–51%). Other common reasons included “more public acceptance and knowledge about COPD” (22%) and “better diagnostics/earlier diagnosis of COPD” (21%). Despite the view of an improved health outlook for patients with COPD, a large proportion of physicians still felt that their patients find it difficult to cope with their disease (Table 1 and Table S2).

While physicians largely attributed the improved prognosis to the availability of better medications, unmet needs for modifying the natural history of the disease were noted; about half (46%; range, 28%–81%) agreed or somewhat agreed that “there are no current treatments that can reduce mortality or halt COPD progression” (Table 1 and Table S2). With regard to COPD physiology, physicians universally agreed that “inflammation is a key component of COPD that should be treated” (92%; range, 86%–97%) and that “more frequent exacerbations are linked to a greater loss in lung function” (93%; range, 86%–100%) (Table 1 and Table S2).

| Table 1 Physician beliefs and knowledge about COPD prognosis and treatment: Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey, 2012–2013 |

When queried about patient access to medication, one in three physicians (30%) stated that none of their patients had any issues accessing the treatments they prescribed; 7% reported that more than half their patients could not access preferred treatments (Figure 1). However, these proportions varied greatly by country, with the highest rates of treatment access restrictions reported in the USA, Mexico, and Brazil (Table S3). The most frequently reported barrier to medication access across most countries was related to cost (“too expensive for patient” or “insurance barriers”). Exceptions included Italy, where “patient refusal to use prescribed medicine”, and the Netherlands where “side effects of preferred treatment” was commonly cited. As well, one-third to one half of physicians in the UK, Mexico, Russia, and South Korea mentioned that they were not able to use preferred treatments as they were “not recommended by local guidelines” or were “not on the clinic/hospital formulary”.

When asked to estimate the percentage of their patients on COPD maintenance medication who fully comply with treatment instructions, only 15% reported that more than three-quarters were fully compliant (range, 5%–26%) (Table S4). Major problems associated with poor compliance were reported to be “poor inhaler technique” (60%; range, 34%–87%), “low patient education/poor understanding of the disease” (57%; range, 47%–69%), “difficulties in managing multiple dosing regimens” (52%; range, 40%–64%), “no perceived benefit of treatment” (46%; range, 30%–66%), and “medication costs” (44%; range, 6%–89%). While physicians in most countries regarded “troublesome side effects” as a minor problem affecting patient compliance with treatment instructions, over 50% of physicians in Russia and Japan reported it as a major problem. “Medication costs” was reported as a leading challenge related to compliance by fewer than 10% of physicians in France, UK, and the Netherlands, in contrast to more than 80% in the USA, Mexico, and Brazil.

Comparison between physician and patient beliefs and reporting of management practices

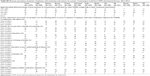

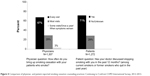

Several questions about COPD perceptions were asked in both the physician and patient surveys. A similar proportion of both physicians (39%) and patients (46%) strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement “there are no truly effective treatments for COPD” (Figure 2). There was some variation across countries in physician response from 19% (USA) to 72% (Russia), while this belief among patients ranged from 26% (Italy) to 63% (South Korea) (Table S5).

| Figure 2 Comparison of physician and patient beliefs about treatment effectiveness: Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey, 2012–2013. |

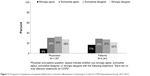

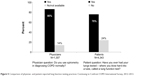

In contrast, there was a considerable difference between physicians and patients regarding their views on the statement “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD” with 78% of physicians strongly agreeing, compared with only 38% of patients (Figure 3). One-third of patients somewhat (17%) or strongly (14%) disagreed with this statement, compared with 3% of physicians (Table S5). Given this large disparity, we explored patient characteristics associated with disagreement in a multivariate logistic regression model (Table S6). Factors independently associated with disagreeing that “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD” were as follows: never smoking (OR [odds ratio], 4.4; 95% CI [confidence interval], 3.6–5.4), former smoking (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–1.9), exposure to dust and fumes at home or in the workplace (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0–1.4), and female sex (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3–1.7). Younger patients and those with more than secondary school education were also more likely to disagree that smoking is the primary cause of COPD. In contrast, patients with a physician diagnosis of COPD (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7) or chronic bronchitis (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.6) were less likely than those who qualified based on a symptom-based definition of chronic bronchitis to disagree about the causal role of smoking in COPD.

| Figure 3 Comparison of physician and patient beliefs about smoking as a risk factor for COPD: Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey, 2012–2013. |

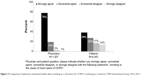

Questions regarding how physicians manage COPD, including smoking cessation counseling for smoking patients, and the use of lung function tests, were also asked of both physicians and patients. Physicians and patients largely agreed about the provision of smoking cessation counseling to current (or recently quitting) smokers (Figure 4 and Table S5). Sixty-seven percent (range, 44%–88%) of physicians reported that they counseled their smoking patients at every clinic visit and 29% (range, 11%–48%) at most visits. This was corroborated by 71% (range, 35%–87%) of smoking patients, indicating that they had received smoking cessation counseling in the past year. When examining patient–physician comparisons within individual countries, Japanese, Dutch, and German physicians were slightly less likely to report that they counseled their patients at every/most clinic visit, which corresponded with rates of smoking cessation counseling reported by patients in these same countries.

| Figure 4 Comparison of physician- and patient-reported smoking cessation counseling practices: Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey, 2012–2013. |

When questioned about lung function testing practices, the majority of physicians (86%) and patients (76%) reported that they used (or had undergone) spirometry testing (Figure 5 and Table S5). Physician responses were consistent across countries (>85% reported spirometry use) except Italy (37%) and France (63%), where a high proportion of PCPs indicated that this testing option was not available in their practice. These findings from France and Italy were supported by responses from the patient survey, as French (28%) and Italian (56%) patients were among the lowest to report that they had received lung function testing. Of interest, discordance between physicians and patients on this topic was seen in Russia (100% of physicians reported that they use spirometry versus 59% of patients indicating they received a lung function test) and Mexico (88% of physicians versus 57% of patients).

| Figure 5 Comparison of physician- and patient-reported lung function testing practices: Continuing to Confront COPD International Survey, 2012–2013. |

Discussion

The Continuing to Confront COPD International Surveys provide an insight into physicians’ views about COPD outlook and management, and an opportunity to compare physician and patient attitudes and beliefs about COPD. Key findings from the physician survey include a perceived improvement about the health outlook for patients with COPD, primarily associated with the availability of better treatments. Despite these better treatments, physicians highlighted patient access to preferred treatment and patient compliance to maintenance treatment as problematic in many regions. Across most countries, physicians reported regular use of spirometry to diagnose COPD and indicated that smoking cessation counseling to smoking patients was a routine part of their COPD management; these findings were corroborated by the patient survey. We observed discordance between physicians and patients regarding the statement “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD”.

The majority of physicians reported that the long-term health outlook for patients with COPD has improved compared with 10 years ago, and while this was largely attributed to the availability of better medications (86% of physicians), approximately a quarter also attributed the better outlook to smoking cessation and improved public awareness about COPD. Only a third of physicians felt that their patients had no problems accessing preferred treatments; cost and issues of insurance coverage were reported as the biggest factors associated with problems of access to medicines. These data varied greatly by country; physicians from USA, Brazil, and Mexico reported the most issues with access (>90% physicians) compared with lower reporting in the UK (34%), Italy (12%), and the Netherlands (11%), reflecting differences in health care delivery and direct costs to patients between countries (eg, national versus privatized systems). In the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey conducted in the USA in 2003–2004, approximately two-thirds believed that reimbursement standards for medical management of patients with COPD were inadequate or very unreasonable, showing that this issue is pervasive in the USA and continues to be a barrier to COPD care.16

Only 15% of physicians in our survey reported that more than three-quarters of their patients on maintenance therapy for COPD were fully compliant in taking their medications, highlighting noncompliance as a major challenge in COPD management. Across countries, the two most common reasons associated with noncompliance were poor inhaler technique and poor patient education/understanding of disease. These findings are consistent with those reported in a recent review of treatment adherence issues in COPD, in which on average 40%–60% of patients were considered adherent to their medications and only one in ten of those prescribed a metered dose inhaler was reported to use it completely correctly.18 Similar to our findings, previous reviews cite many possible reasons for poor compliance, including those related to medicine/device factors (eg, difficulties with inhalers, complex regimens, side effects) and patient factors (eg, misunderstanding medication instructions, undiscussed fears/concerns, cultural issues).18,19 To achieve optimal compliance, patients should have a clear understanding of the need for their treatment, which takes account of specific concerns, and treatment should be convenient and as easy to use as possible.20

For topics covered in both surveys, there was good agreement between responses about COPD treatment effectiveness, smoking cessation practices, and use of spirometry, both overall and within countries, suggesting a good degree of credibility in the self-reported physician responses. Approximately two fifths of both patients and physicians strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement “there are no truly effective treatments for COPD”, despite many physicians noting that the introduction of better treatments has played a role in improving the long-term health outlook for patients with COPD. A similar pattern was reported by Barr et al16 in the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey, where 68% of physicians reported an improved COPD outlook due primarily to better medications, yet almost a third agreed or strongly agreed that “there are no truly effective treatments for COPD”.

Regarding physician diagnosis and management practices, the high level (86%) of self-reported use of spirometry by physicians in the Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey13 was corroborated with 76% of patients reporting that they had undergone a lung function test. The provision of smoking cessation counseling to smokers was also reported by the majority of both physicians and patients; however, a key discordance was observed in their beliefs about the statement “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD”. Other published studies comprised primarily of patients with COPD who currently smoke have also shown that patients more often cite non-smoking-related causes of COPD than physicians.16,21 There was some geographic variability regarding patient belief about the role of smoking, but this did not appear to be related to smoking prevalence rates in a particular country. For example, Japan and Korea have some of the highest global smoking rates,22 and respondents in these countries were also most likely to disagree with the statement (Table S5); however, this pattern did not hold in Russia, the UK, Spain, and France, which also feature medium-to-high smoking prevalence yet were least likely to disagree about the role of smoking in COPD. Also, the results did not track geographically with countries that have a higher use of biofuels, another recognized risk factor associated with COPD.23 Thus, it appears that other patient factors may play a role in patient beliefs. We explored this further in our sample and identified that self-reported nonsmokers were the most likely group to disagree with the statement “smoking is the cause of most cases of COPD”, even after adjusting for other patient factors, and this finding was consistent in all countries (ORs for nonsmokers versus smokers ranged from 1.5 to 11.7; full data not shown). Despite implementation of awareness campaigns about the risks of smoking,24 it may not be surprising that some nonsmokers express doubt that smoking is a primary cause of COPD given their lack of personal smoking exposure. Similarly, we saw that ex-smokers who may have quit years before their diagnosis were also slightly more likely to disagree with this statement. We also observed that patients with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of COPD or chronic bronchitis were half as likely as those who qualified with symptoms only to deny a causal role of smoking in COPD, suggesting that educational messages about the importance of smoking cessation are more effectively reaching patients with COPD than the general public. These results can be helpful in identifying groups, such as nonsmokers, women, and younger adults, who may most benefit from targeted educational interventions about the risks of smoking.

Our findings must be interpreted within the limitations of this type of survey. As discussed in detail in previous publications about this survey, the representativeness of the samples within certain countries may be limited due to variable response rates in the Patient and Physician surveys.13,14 In addition, the comparison of physicians’ and patients’ perceptions may be impacted by differences in knowledge and priorities between these groups. For example, patients and physicians will bring underlying assumptions about treatment effectiveness that may impact their responses to statements such as “there are no truly effective treatments for COPD”. Similarly, beliefs about smoking as a cause of the majority of cases of COPD will be subject to a patient’s personal risk factor profile, as well as regional variation in the frequency of other established risk factors such as biomass fuel and other occupational exposures.

In conclusion, the Continuing to Confront COPD International Surveys demonstrated that physician perception about the health outlook for patients with COPD has improved in the past decade, largely attributed to improved medications, although patient access to therapy remains problematic in many areas. Many physicians and patients agreed with the statement that “there are no truly effective COPD treatments”, suggesting that further efforts to move toward a precision medicine approach for treating specific COPD phenotypes are warranted. There was a considerable gap between physicians’ and patients’ perceptions about whether smoking is the cause of the majority of cases of COPD, highlighting a need for enhanced and targeted patient education about the risks of smoking.

Acknowledgments

The survey was conducted by Abt SRBI, a global survey research firm that specializes in health surveys. The authors acknowledge editorial support in the form of draft manuscript development, assembling tables, collating author comments, and copyediting, which was provided by Kate Hollingworth of Continuous Improvement Ltd. The authors further acknowledge the analytical support provided by Joe Maskell. This support was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Disclosure

This study was funded by GSK. All authors meet the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. SL, KD, and HM are employees of GSK and hold GSK shares. Y-MO, DM, MH, TvdM, ZA, AM, and MI served on the Scientific Advisory Committee for the Continuing to Confront COPD Survey and were paid for advisory services. Scientific Advisory Committee members were not paid for authorship services. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (GOLD) [revised 2014]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com. | ||

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. | ||

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. | ||

Corrado A, Rossi A. How far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational study. Respir Med. 2012;106:989–997. | ||

Aisanov Z, Bai C, Bauerle O, et al. Primary care physician perceptions on the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in diverse regions of the world. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:271–282. | ||

Glaab T, Vogelmeier C, Hellmann A, Buhl R. Guideline-based survey of outpatient COPD management by pulmonary specialists in Germany. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:101–108. | ||

Rutschmann OT, Janssens J-P, Vermeulen B, Sarasin FP. Knowledge of guidelines for the management of COPD: a survey of primary care physicians. Respir Med. 2004;98:932–937. | ||

Fukuhara S, Nishimura M, Nordyke RJ, Zaher CA, Peabody JW. Patterns of care for COPD by Japanese physicians. Respirology. 2005;10:341–348. | ||

Laniado-Laborín R, Rendón A, Alcantar-Schramm JM, Cazares-Adame R, Bauerle O. Subutilization of COPD guidelines in primary care: a pilot study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4:172–176. | ||

Yawn BP, Wollan PC. Knowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical education. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:311–317. | ||

Desalu OO, Onyedum CC, Adeoti AO, et al. Guideline-based COPD management in a resource-limited setting–physicians’ understanding, adherence and barriers: a cross-sectional survey of internal and family medicine hospital-based physicians in Nigeria. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22:79–85. | ||

Hernandez P, Balter MS, Bourbeau J, Chan CK, Marciniuk DD, Walker SL. Canadian practice assessment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: respiratory specialist physician perception versus patient reality. Can Respir J. 2013;20:97–105. | ||

Davis KJ, Landis SH, Oh Y-M, et al. Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey: physician knowledge and application of COPD management guidelines in 12 countries. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. In press. | ||

Landis S, Muellerova H, Mannino DM, et al. Continuing to Confront COPD International Patient Survey: methods, COPD prevalence, and disease burden in 2012–2013. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1–15. | ||

Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PMA, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:799–805. | ||

Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med. 2005;118:1415. | ||

Sayiner A, Alzaabi A, Obeidat NM, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about COPD: data from the BREATHE study. Respir Med. 2012;106:S60–S74. | ||

Restrepo RD, Alvarez MT, Wittnebel LD. Medication adherence issues in patients treated for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:371–384. | ||

Mäkelä MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, Larsson K. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107:1481–1490. | ||

Horne R, Chapman SCE, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80633. | ||

Bjarnason NH, Mikkelsen KL, Tønnesen P. Smoking habits and beliefs about smoking in elderly patients with COPD during hospitalisation. J Smok Cessat. 2010;5:15–21. | ||

World Health Organization. Prevalence of Tobacco Use Among Adults and Adolescence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/tobacco/use/atlas.html. Accessed August 2014. | ||

Ramírez-Venegas A, Pérez-Padilla R, Rivera RM, Sansores RH. Other causes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: exposure to biofuel smoke. Hot Top Respir Med. 2007;4:7–13. | ||

Walsh JW. The evolving role of COPD patient advocacy organizations for COPD. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:676–680. |

Supplementary materials

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.