Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

“Comparisons are Odious”? — Exploring the Dual Effect of Upward Social Comparison on Workplace Coping Behaviors of Temporary Agency Workers

Received 15 July 2023

Accepted for publication 13 September 2023

Published 18 October 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4251—4265

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S425946

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Yi Li,* Siyu Wang*

School of Management, Shanghai University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Siyu Wang, Shanghai University, 20 Chengzhong Road, Jiading District, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 15510031225, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Temporary agency workers are becoming increasingly critical as a supplementary workforce within enterprises, inevitably leading upward social comparisons with permanent employees. However, existing research pays little attention to this phenomenon, which cannot provide theoretical guidance for the management of temporary agency workers. To fill this gap, our study utilizes the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion to construct a dual-path moderated mediation model, examining how upward social comparison is associated with positive and negative behaviors through two distinct forms of envy. Through the questionnaire survey, data is collected from 882 temporary agency workers in a Chinese temporary staffing firm. The results reveal that upward social comparison is associated with both benign and malicious envy, which in turn respectively relate to informal workplace learning and social undermining behavior. Additionally, psychological availability moderates the relationship between upward social comparison and envy, such that when psychological availability is higher (vs lower), the positive effect of upward social comparison on benign envy is stronger and the positive effect of upward social comparison on malicious envy is weaker. Moreover, psychological availability further moderates the indirect effect of upward social comparison on employee behavior. When psychological availability is higher (vs lower), the positive indirect effect of upward social comparison on informal workplace learning via benign envy is stronger, whereas the positive indirect effect of upward social comparison on social undermining via malicious envy is weaker. Our study enriches the theoretical research perspective of upward social comparison and provides insights for managing temporary agency workers. Our study is the first to explore the dual behavioral choices of upward social comparison of temporary agency workers and apply the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion to social comparison. The results indicate that organizations can improve the psychological availability of temporary agency workers to stimulate learning behavior and reduce social undermining behavior to achieve a win-win situation between temporary agency workers and organizations.

Keywords: upward social comparison, envy, psychological availability, informal workplace learning, social undermining

Introduction

As the sharing economy and the VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) era approach, a growing number of companies are hiring temporary agency workers to reduce labor costs, mitigate management risks, and enhance organizational flexibility.1 Compared with permanent employees, temporary agency workers typically encounter more workplace disadvantages, such as lower pay and fewer benefits,1 lower job security,2 and lower job satisfaction.3 They also grapple with issues like workplace stigmatization and job discrimination.4,5 Continual exposure to such an environment inevitably leads temporary agency workers to make upward social comparisons with permanent employees who are in better circumstances.6 Thus, the question arises: will comparing themselves to superior permanent employees ignite positive behaviors inspired by a desire for self-improvement, or spark negative behaviors born out of envy? Exploring the implications of upward social comparison is crucial for effectively managing agency workers and fully utilizing human capital.

However, most of the existing research seldom addresses upward social comparisons in the workplace, focusing more on social media contexts. For instance, studies show that upward social comparisons on social media can lead to anxiety, and depression, reduce life satisfaction, and subjective well-being, and provoke malicious comments.7–9 Despite the workplace being a significant component of employees’ social lives,10,11 it has not received due attention. The upward social comparison of temporary agency workers has not yet received academic attention. Consequently, we still know little about its influence and mechanism, which cannot provide evidence for management practice.

Based on the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, our study intends to bridge this gap by exploring the effects and mechanisms of upward social comparison on the psychology and behavior of temporary agency workers. The cognitive appraisal theory of emotion posits that an individual’s appraisal of environmental events determines their emotional responses and subsequent behavior.12,13 Given that the workplace is essentially a competitive and self-interested environment,10,14 upward social comparison allows individuals to identify the gap between themselves and their colleagues, leading to psychological inferiority, self-threat, and negative emotions.15 As one of the most common negative emotions following comparative behavior, envy is inherently painful, yet benign envy focuses on self-improvement, and malicious envy focuses on harming others.16 Therefore, this focus shift might result in opposing behaviors: positive and negative. Informal learning, the most common form of learning in the workplace,17,18 effectively enhances personal capabilities and competence, while social undermining, a subtle and unnoticeable disruptive behavior,19 negatively impacts others. Therefore, our study explores the effect of upward social comparison, triggering benign and malicious envy, which subsequently induces informal workplace learning and social undermining, respectively.

Furthermore, our study aims to reveal the boundary conditions under which upward social comparison stimulates benign or malicious envy. According to the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, individuals’ self-assessments of their abilities to cope with situations and their future expectations can affect the emotions they experience.13 Psychological availability is “the sense of having the physical, emotional, or physiological resources to personally engage at a particular moment”.20 High psychological availability is a positive self-evaluation and will play a more positive role when comparing oneself with superior individuals, thus moderating subsequent emotions and behavior. Generally, the higher an employee’s psychological availability, the more resources they perceive as accessible, and the more likely they are to assess their potential for coping and future expectations positively. As a result, they increase their positive behaviors and decrease their negative behaviors. Consequently, our study further investigates the moderating effect of psychological on upward social comparison process.

The major contributions of this study are: (1) addressing the unique needs of temporary agency workers and filling the gap in the research on upward social comparisons in the workplace, responding to the call by Greenberg et al to focus on social comparison processes in organizations;11 (2) providing a novel theoretical perspective – the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion – to explain how upward social comparison influences employee behavior. This study establishes a framework on the influence of upward social comparison on positive and negative behavior choices through different types of envy, enriching the field of upward social comparison and extending the research on the impact of benign and malicious envy; (3) revealing the boundary conditions of the psychological and behavioral impact of upward social comparisons on temporary agency workers. By selecting psychological availability, a self-resource evaluation, as the boundary condition, our study constructs a dual-path moderated mediation model.

Theory and Hypotheses

Upward Social Comparison and Envy

Social comparison theory suggests that individuals evaluate their own situation and group status by comparing themselves to those in close contact,21 either those who are better off on certain characteristics or dimensions, such as salary, abilities, and relationships with leaders (upward social comparison) or those who are worse off (downward social comparison).22 Temporary agency workers are often hired to fill labor shortages and work alongside permanent employees.23 The coexistence of different types of employees leads to automatic social comparison, and consequently, permanent employees are the comparison objects of temporary agency workers.6 Compared with downward social comparison, upward social comparison occurs when an individual has a lower status, and an individual’s environment will impact the social comparison process.8,24 Because temporary agency workers can feel differential treatment with permanent employees anytime and anywhere in the working environment, the upward social comparison of temporary agency workers at a disadvantage is more prominent.

Temporary agency workers often receive inconsistent treatment in terms of compensation, company training, and daily management activities compared to permanent employees,25 leading to negative self-evaluations as they compare their abilities, income, and life circumstances to the higher standards of permanent employees.26 According to the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion,13 emotions are an adaptive response to the external environment. Environmental events trigger cognitive processes in individuals to evaluate whether they are beneficial or harmful to themselves, thus generating specific emotions. Therefore, envy may occur when a temporary agency worker perceives a lack of superior quality, achievement, or possession that the other has and either desires it or wishes that the other lacked it.27 Existing studies have proven that upward social comparison can induce feelings of envy,25,28 but envy in these studies is often considered a form of hostile mentality with malicious intent.

As research has progressed, scholars have begun to distinguish between benign and malicious envy. Malicious envy is filled with hostility and resentment, with the envier wishing for the downfall of those they envy. Conversely, benign envy can be perceived as a motivational force, prompting individuals to strive harder to attain what others have.29 This kind of benign, competitive envy can increase an individual’s desire to obtain what the person envied possesses, but without the hostility and resentment of malicious envy. Salerno et al proposed that benign envy and malicious envy share a common origin, ie, feelings of inferiority and pain caused by upward social comparison.30 Therefore, upward social comparison may elicit two different reactions. On the one hand, temporary agency workers, when perceiving themselves at a disadvantage, may develop resentment and hostility toward their comparison counterparts, wishing for them to lose their privileges, thereby engendering malicious envy. On the other hand, feeling inferior to others can also stimulate the motivation of temporary agency workers to surpass their comparison counterparts, thereby giving rise to benign envy. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: Upward social comparison is positively related to benign envy. H1b: Upward social comparison is positively related to malicious envy.

The Mediating Role of Envy

Benign envy can stimulate individuals to develop positive motivations, shifting their attention from envy to methods for achieving similar success to the one envied.31,32 Thus, benign envy leads to self-improvement behavior to match or exceed the levels of those who are envied. Workplace learning refers to the process of enhancing employees’ human capital by acquiring knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics,33 and primarily involves formal and informal learning. Formal learning refers to “off-The-job” structured learning, such as participating in organizational training activities, while informal learning is a non-structured learning activity initiated and controlled by the learner. Employees can self-regulate their learning process according to work needs, unrestricted by time and location.34 Informal learning is also considered the most common method of learning in the workplace,17,18 serving as an important way for employees to improve their work skills and achieve better career development. For temporary agency workers, companies mostly only provide new employee orientation training, with the training content often being simple job-related skill training. Therefore, compared to formal learning, temporary agency workers are more likely to adopt self-directed informal learning methods to improve themselves. In other words, temporary agency workers who experience benign envy may attempt to close the gap with those they envy through informal workplace learning.

According to the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, an individual’s evaluation of environmental events first affects their emotional responses, thereby prompting individuals to make behavioral choices consistent with them. Considering the above discussion and the prediction in H1a that upward social comparison is positively related to benign envy, this study proposes that upward social comparison generates benign envy, leading temporary agency workers to engage in informal workplace learning behaviors. Specifically, the upward social comparison makes temporary agency workers lower their self-evaluations, inducing feelings of inferiority and frustration but also making them aware of the gap between themselves and permanent employees, prompting motivation for self-improvement.35,36 Benign envy encourages temporary agency workers to achieve their desired outcomes through “challenging behaviors”,16,37 that is, to generate informal workplace learning behaviors. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2a: Benign envy mediates the effect of upward social comparison on informal workplace learning so that upward social comparison has a positive indirect effect on informal workplace learning through benign envy.

Individuals experiencing malicious envy believe that they cannot reach the same level as others, and in this case, it is more meaningful to change the standard to reduce the threat that arises from upward social comparison. Therefore, the reaction of the envier is to attempt to lower the level of the envied,38 such as implementing schadenfreude, slander, hostility, and belittlement.16,39 Unlike benign enviers who turn their attention to their own efforts, malicious envy enviers shift their focus to the envied, hoping that the envied lose their advantages and their success is ruined. Thus, temporary agency workers experiencing malicious envy are likely to diminish the advantages of those they envy by damaging their interpersonal relationships, reputation, etc. Social undermining refers to behaviors intended to hinder, over time, the ability to establish and maintain positive interpersonal relationships, work-related success, and favorable reputation, such as delaying someone’s work, withholding important or required information, giving someone the silent treatment, speaking ill of someone behind their back, spreading rumors about someone. Social undermining behaviors are covert and hard to detect, and the impact on others is also a long-term, gradual process.19 Therefore, compared to more intense forms of abuse like attacking, low-level forms of abuse such as social undermining are more likely to occur. Individuals experiencing malicious envy usually strive to restore a sense of balance, reducing feelings of inferiority and frustration caused by envy. Therefore, our study believes that social undermining is a potential way to minimize others’ achievements. Through social undermining, temporary agency workers can reduce others’ superiority, elevate their own status, and vent their frustration and hostility.40 Due to the peculiarity of the employment relationship, the identity cognition of temporary agency workers as “external people” in the organization makes them separate the organization from their self-concept,41 resulting in a lower sense of belonging, identification, and loyalty to the organization. Moreover, they do not need to maintain long-term working relationships with other members, and given the covert nature of social undermining behaviors, temporary agency workers experience less psychological pressure when undermining their colleagues, not easily bound by emotional and moral constraints. Therefore, temporary agency workers experiencing malicious envy are more likely to engage in social undermining behaviors.

Based on the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion and the above discussion, as well as the prediction in H1b that upward social comparison is positively related to malicious envy, this study suggests that upward social comparison induces malicious envy, leading temporary agency workers to engage in social undermining behaviors. Specifically, upward social comparison leads temporary agency workers to feel “inferior to others”, causing resentment and hostility towards the compared object, and desire for the compared object to lose their advantages, ie, generating malicious envy. To maintain a positive self-evaluation and reduce the painful perception brought by self-threat, temporary agency workers will adopt a series of coping behaviors to narrow the gap between self-evaluation and the comparison standard.42,43 Therefore, temporary agency workers experiencing malicious envy are likely to destroy others’ success through social undermining. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2b: Malicious envy mediates the effect of upward social comparison on social undermining so that upward social comparison has a positive indirect effect on social undermining through malicious envy.

The Moderating Role of Psychological Availability

Based on the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, the evaluation of the person’s options and resources for coping with the situation and future prospects often has a crucial influence on which individual emotion is experienced.13 This assessment and interpretation process may be influenced by psychological availability. Psychological availability refers to the individual’s belief that they have physical, emotional, or psychological resources with which to work, essentially reflecting the individual’s preparedness and confidence for their work.44 Psychological availability can enhance employee energy and creativity,45,46 leading to more positive behaviors such as knowledge sharing behavior.47 Therefore, the perception of an individual’s available resources will affect the evaluation of one’s own coping potential and future expectations, that is, it will affect the cognition of the results of upward social comparison, and thus affect emotional responses. Specifically, temporary agency workers with high psychological availability may believe that they maintain control over personal outcomes, have the ability and resources to gain the advantages of the compared object, and anticipate that they may achieve the same level of the compared people in the future. In this case, upward social comparison will stimulate the motivation of employees to improve themselves, reduce the hostility and destructive motivation to the compared object, that is, enhance the benign envy and alleviate the malicious envy. On the contrary, if temporary agency workers have low psychological availability, they may perceive they cannot control personal outcomes, cannot gain the advantages of the compared object with the ability and resources they possess, and anticipate that they cannot achieve the level of the compared people through self-improvement. In this case, upward social comparison will stimulate the destructive motivation caused, reduce the self-promotion motivation, that is, strengthen the malicious envy and weak the benign envy. Collins’ research also demonstrated that an individual’s expectations have a decisive impact on the outcome of upward social comparisons.26 Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a: Psychological availability moderates the positive relationship between Upward social comparison and benign envy, such that the relationship is stronger when psychological availability is high. H3b: Psychological availability moderates the positive relationship between Upward social comparison and malicious envy, such that the relationship is weaker when psychological availability is high.

Additionally, temporary agency workers with high psychological availability are likely to believe they possess sufficient resources to handle work-related threats and anticipate that they can reach the level of the compared object. According to the conservation of resources theory, individuals with abundant resources can better resist resource loss, have more opportunities to gain new resources through investment, and will experience less stress, and generate more positive behaviors.48,49 Therefore, such temporary agency workers may experience benign envy to mitigate the self-threat from upward social comparison, driving them to undertake informal workplace learning for self-improvement. Conversely, temporary agency workers with low psychological availability may perceive their resources as inadequate for meeting work demands or gaining the advantages of the compared object, leading to malicious envy. They may engage in social undermining behaviors to reduce the pain of self-threat. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a: Psychological availability moderates the indirect effect of upward social comparison on informal workplace learning via benign envy, such that the indirect effect is stronger when psychological availability is high. H4b: Psychological availability moderates the indirect effect of upward social comparison on social undermining via malicious envy, such that the indirect effect is weaker when psychological availability is high.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The geographical distribution of temporary staffing firms is mainly concentrated in first-tier cities and economically developed areas. These areas (eg, Shanghai) have a relatively high economic level, rich human resources, and a large number of enterprises. Hence, the market demand for temporary staffing firms is also relatively large. In addition, the preferential policies provided by Shanghai to temporary staffing firms have further promoted their development. Therefore, we chose a large-scale temporary staffing firm in Shanghai that involves many industries as the research sample. We designed an online questionnaire, and the person in charge of the temporary staffing firm posted the questionnaire link. In the informed consent information, we explained the purpose of the research, assured that the data was only used for academic research and would remain confidential, and reminded participants that they could withdraw from the research at any time. We also endeavored to make the questionnaire item explanations as precise and clear as possible to minimize ambiguity. To reduce common method bias, we conducted a three-wave survey with a time interval of two weeks. In order to match responses from the three waves, participants were requested to indicate their initials as well as their last 4 digits of an 11-digit mobile phone number in each survey.

In the first wave (T1) survey, 1045 participants reported upward social comparison, psychological availability and their own demographics. At Time 2 (two weeks after T1), 983 participants reported two types of envy (benign and malicious envy), resulting in a response rate of 94.07%. At Time 3 (two weeks after T2), 899 participants reported informal workplace learning and social undermining, resulting in a response rate of 86.03%. 17 participants that changed jobs during the survey period were excluded. Among the final sample of 882, 425 (48.2%) were female, the average age was 27.53 (SD=8.288), 53.4% had a junior middle school education, 33.7% had a high school education, and 2% had a bachelor’s degree or above. 61.8% became temporary agency workers for less than one year, 33.8% for 1–5 years, and only 4.4% for more than five years. The lowest average monthly salary is less than 2000 yuan, accounting for 6.8%; the largest proportion is 73.4% for 3000 to 5000 yuan, and the highest is 8000 to 9000 yuan, accounting for 1.6%.

Measures

Surveys were administered in Chinese. To confirm the accuracy of the translation and correct any discrepancies, we employed the translation and back-translation process before distributing the questionnaires to respondents. Five-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) were used in all scales.

Upward Social Comparison

We used the subscale from Gibbons and Buunk Social Comparison Scale to measure it.50 The scale consists of 6 items, sample items include “I often compare myself with people who are doing better than me”. (Cronbach’s α=0.894).

Benign and Malicious Envy

Benign and malicious envy were measured by a 10-item scale developed by Lange and Crusius,51 with 5 items each. Benign envy items included “When I envy others, I focus on how I can become equally successful in the future” and “If I notice that another person is better than me, I try to improve myself”, while malicious envy items included “I wish that superior people lose their advantage” and “If other people have something that I want for myself, I wish to take it away from them”.(Cronbach’s α=0.865; Cronbach’s α=0.919).

Informal Workplace Learning

Informal workplace learning was measured using an 8-item scale developed by Decius et al.52 A sample item is: “I use my own ideas to improve tasks at work”. (Cronbach’s α=0.870).

Social Undermining

Social undermining was measured by the colleague undermining scale from Duffy et al,19 which we adapted to measure the degree to which employees enact undermining behavior towards their colleagues. The scale included 13 items, such as “I gave silence treatment to my colleagues”. (Cronbach’s α=0.960).

Psychological Availability

Psychological availability was measured using a 5-item scale developed by May et al.44 Sample items included “I am confident in my ability to handle competing demands at work”, and “I am confident in my ability to display the appropriate emotions at work.” (Cronbach’s α=0.963).

Control Variables

We controlled for employees’ gender, age, education, years of working, and monthly income considering previous research finding significant relationships between these characteristics and informal workplace learning, and social undermining.53,54

Analytical Strategy

First, we conducted the confirmatory factor analysis to test the variables’ discriminative validity. To test hypotheses, we utilized Mplus 8.3 for path analysis. Path analysis can deal with multiple dependent and intermediary variables simultaneously, which can make up for the defects of a single linear regression relationship model, better reflect the overall characteristics of indirect effects, and more in line with the actual situation of the research object. For the test of mediating effects, we constructed the confidence intervals (CIs) by bootstrapping the indirect effect 5000 times. The indirect effect is significant if its 95% CIs exclude zero. For the additional test of mediating effects, we plotted simple slope tests (±1 SD of psychological availability). In examining the moderated mediating effect, we estimated the indirect effects at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of psychological availability. The conditional indirect effect is significant if its 95% CIs exclude zero.

Results

Discriminant Validity Tests and Common Method Bias Tests

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using Mplus8.3 to verify the discriminant validity of the variables. As shown in Table 1, the theorized six-factor model fit the data significantly better than other models (TLI=0.909; CFI=0.915; RMSEA=0.066; SRMR=0.071). The results supported the discriminant validity of the key variables in our model.

|

Table 1 Discriminant Validity and Common Method Bias Tests |

Harman’s single-factor test was employed to examine potential common method bias. The results showed that the cumulative variance explanation for all factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 was 73.859%, and the variance explanation for the unrotated largest factor was 26.843%, which is below the 40% critical standard. For further test, the method factor with all the measurement items as indicators is introduced in this study.55 The results showed that the model fitting data did not improve significantly when the method factor was added to the six-factors model (ΔTLI=0.026; ΔCFI=0.027; ΔRMSEA=−0.011; ΔSRMR=−0.028). CFI and TLI were reduced by less than 0.1, and RMSEA and SRMR were reduced by less than 0.05, indicating the common method bias is not a serious confounding influence on our empirical results.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 represents the means, standard deviations, correlations among variables internal consistency coefficients of the scales. Upward social comparison was positively related to informal workplace learning (r=0.101, p<0.01), social undermining (r=0.360, p<0.001), benign envy (r=0.221, p<0.001), and malicious envy (r=0.332, p<0.001). Benign envy was positively related to informal workplace learning (r=0.360, p<0.001), while malicious envy was positively related to social undermining (r=0.282, p<0.001). These results provide preliminary support for our hypotheses and form the basis for subsequent regression analysis.

|

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations |

Hypotheses Testing

Mplus 8.3 was used to conduct path analysis of the model as a whole and we centralized each variable in order to accurately estimate the mediating and moderating effects. The result of path analysis is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The path analysis results of model. Notes: The path coefficients in the figure are non-standardized coefficients. This model includes control variables (omitted). ***p<0.001, **p<0.01. |

H1 predicted that upward social comparison would positively relate to benign envy (H1a) and malicious envy (H1b). As shown in Figure 1, upward social comparison positively affects benign envy (β=0.249, p<0.001) and malicious envy (β=0.212, p<0.001), supporting H1a and H1b.

The mediating effect was analyzed with 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals (CIs) of 5000 repeated samples. As shown in Figure 1, The indirect effect of upward social comparison on informal workplace learning via benign envy was 0.058 (p<0.001, 95% CI=[0.041, 0.076]). The indirect effect of upward social comparison on social undermining via malicious envy was 0.075 (p<0.001, 95% CI=[0.050, 0.108]). The confidence interval of the above results did not contain 0, H2a and H2b were supported.

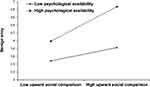

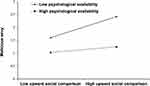

H3 predicted that psychological availability would moderate the relationship between upward social comparison and envy. As shown in Figure 1, Psychological availability significantly moderated the relationship between upward social comparison and benign envy (β=0.105, p<0.01), and the relationship between upward social comparison and malicious envy (β=−0.115, p<0.01). Thus, H3a and H3b were supported. To further examine the nature of this interaction, we plotted simple slope tests (±1 SD of psychological availability).56 As shown in Figure 2, the positive relationship between upward social comparison and benign envy was significantly stronger when psychological availability was higher (+1 SD; β=0.360, p<0.001) than when psychological availability was lower (−1SD; β=0.138, p<0.01; diff=0.221, 95% CI=[0.063, 0.394]). Thus, H3a received additional support. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3, the positive relationship between upward social comparison and malicious envy was significantly weaker when psychological availability was higher (+1 SD; β=0.090, p<0.01) than when psychological availability was lower (−1SD; β=0.333, p<0.001; diff=−0.242, 95% CI=[−0.387, −0.089]). Thus, H3b received additional support.

|

Figure 2 The interaction between upward social comparison and psychological availability on benign envy. |

|

Figure 3 The interaction between upward social comparison and psychological availability on malicious envy. |

To test moderated mediation effect, we constructed confidence intervals by bootstrapping the conditional indirect effect 5000 times to test H4. As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of upward social comparison on informal workplace learning via benign envy was significantly stronger when psychological availability was higher (β=0.089, 95% CI=[0.062, 0.121]) than when psychological availability was lower (β=0.034, 95% CI=[0.007, 0.062]), and the difference between these indirect effects was also significant (β=0.055, 95% CI=[0.015, 0.102]). Thus, Hypothesis 4a was supported. Correspondingly, the indirect effect of upward social comparison on social undermining via malicious envy was significantly weaker when psychological availability was higher (β=0.031, 95% CI=[0.008, 0.057]) than when psychological availability was lower (β=0.114, 95% CI=[[0.067, 0.175]), and the difference between these indirect effects was also significant (β=−0.083, 95% CI=[−0.151, −0.029]). Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported.

|

Table 3 Results of Moderated Mediation Effect |

Discussion

The development of the sharing economy and the arrival of the VUCA era indicate that flexible employment will be the development direction of the future workforce. The flexible employment group of temporary agency workers has become an essential force in promoting economic development. With the change in employment forms, there are more and more cases of temporary agency workers working with permanent employees, which makes the employee attitude and behavior mechanism more complicated in the context of diverse employment identities. Organizations pay attention to the impact of temporary agency workers on permanent employees, such as making permanent employees feel threatened, reducing their loyalty to the organization, worsening peer relationships, and increasing turnover behaviors.57,58 Since temporary agency workers often perform temporary, auxiliary, or alternative work, their importance to the organization may be overlooked. However, as a particular, increasingly essential, and less developed human resource, temporary agency workers can improve the organization’s cost-effectiveness and competitive advantage if fully utilized. Given this, it is urgent to help organizations understand the attitude and behavior patterns of temporary agency workers to make good use of this essential human resource.

Existing studies on temporary agency workers pay more attention to the impact of unfair treatment on their psychology, such as job satisfaction, job security, and work autonomy, but ignore the effect on their behavior. Temporary agency workers usually work alongside permanent employees, so they will inevitably make upward comparisons of their abilities, income, living conditions, etc., according to the standards of permanent employees.25 However, to date, only few studies have examined social comparison phenomena in workplaces: Greenberg et al theoretically analyzed the role of social comparison processes in organizational justice, performance appraisal, virtual work environments, affective behavior in the workplace, stress, and leadership;11 Brown et al empirically tested the negative impact of upward social comparisons on job satisfaction and emotional commitment.10 Khan and Noor tested the positive impact of upward social comparison on employees’ work performance.59 All in all, we still know very little about social comparison in the workplace, let alone the influence mechanism of upward social comparison on temporary agency workers.

Given the tendency of temporary agency workers for upward social comparison and the lack of research on upward social comparison in the workplace, our study constructs and empirically tests the mechanism of the influence of upward social comparison on the behavioral choices of temporary agency workers. The analysis underlines a dual effect of upward social comparison on their behavior: it can inspire informal workplace learning via benign envy, while also instigating social undermining via malicious envy. Furthermore, the relationships between upward social comparison and benign envy, and malicious envy are moderated by psychological availability. This is manifested as psychological availability strengthening the positive relationship between upward social comparison and benign envy while weakening the positive relationship between upward social comparison and malicious envy. Finally, psychological availability also moderates the mediating roles of benign envy and malicious envy, specifically, the higher the psychological availability, the stronger the indirect relationship between upward social comparison and informal workplace learning through benign envy, and conversely, the weaker the indirect relationship between upward social comparison and social undermining through malicious envy.

Theoretical Implications

First, our study pays attention to the upward social comparison inclination among temporary agency workers and the lack of research on the impact of upward social comparison on employee behavior in the workplace. Due to their unique employment status, temporary agency workers usually perceive the differential treatment of employing organizations compared to permanent employees.1 As the diversity of employment status in the same department or team increases, temporary agency workers are likely to compare themselves with permanent employees who may be in more favorable conditions. However, existing research overlooks the potential psychological and behavioral implications of such upward social comparison for these workers. Therefore, our study expands the research on the attitudes and behaviors of temporary agency workers, providing more references for organizations to effectively manage this increasingly important flexible workforce. In addition, current studies on upward social comparison mostly concentrate on social media, they seldom consider its impact within one of the most prevalent human behavior environments - The workplace. By studying the behavior choices of temporary agency workers post upward social comparison in the workplace, our study responds to the call of Greenberg et al to focus on the social comparison process in organizations.11

Second, our study provides a new theoretical perspective for explaining the mechanism of the influence of upward social comparison on the behavior choices of temporary agency workers. Previous studies have often used assimilation effects and contrast effects from social comparison theory to explain the opposite emotions and behaviors induced by upward social comparison. The assimilation effect refers to the focus on the similarity of the relationship with the comparison object, which makes the individual enhance their self-evaluation level, leading to positive emotions and behaviors; the contrast effect refers to the focus on the difference with the comparison object, which makes the individual lower their self-evaluation level, leading to negative emotions and behaviors.60 For example, Park et al revealed that upward social comparison on social media provoked upward contrastive emotions, which, in return, induced discontinuance and the posting of malicious comments, while upward assimilative emotions triggered the posting of favorable comments.61 Given that social comparison in the workplace is more likely to evoke contrast rather than assimilation effects,10,14 it is more likely to incite negative emotions and behaviors, and thus contrast effects have difficulty explaining the two opposite behavior choices of temporary agency workers after upward social comparison. Based on the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, our study revisits the relationship between upward social comparison and behavior choices, finding that upward social comparison can indirectly affect informal workplace learning and social undermining through benign envy and malicious envy, thus enriching the theoretical research in this field.

Third, our study proposes and tests the boundary conditions for the effects of upward social comparison on benign envy, malicious envy, and behavioral choices. Previous studies have suggested deservingness and control potential as key factors prompting two different types of envy.62,63 Deservingness is an individual’s judgment of the outcome others achieve,64 while control potential refers to the perceived ability to control or do something about the comparison event.36 Benign envy was experienced when the situation was appraised as both deserved and controllable. Based on the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, our study contends that psychological availability can affect the appraisal of coping potential and future expectations, such that individuals with high psychological availability are more likely to experience benign envy, while those with low psychological availability are more likely to generate malicious envy. This expands the research on the moderating variables in the relationship between upward social comparison and envy. In addition, by identifying the moderating role of psychological availability, our study further explains the impact of upward social comparison on employee behavior choices from the perspective of emotion.

Practical Implications

First, in an environment where upward social comparison is prevalent, improving the psychological availability of temporary agency workers is an effective way to promote benign envy and reduce malicious envy. Previous research suggests that when individuals perceive a low level of uncertainty, their psychological availability increases.46 Hence, managers should clarify the goals and work processes for these employees and provide them with more work resources to decrease the perception of uncertainty. Managers should also establish comprehensive corporate training systems to improve their skills and work capabilities, fulfilling ongoing work demands. Furthermore, managers should attend to these employees’ physical health and emotional needs, provide regular medical examinations, strengthen communication with them, pay attention to their psychological dynamics, provide psychological guidance, etc., to enhance temporary agency workers’ perceptions of their available resources.

Second, upward social comparison can prompt temporary agency workers to engage in informal workplace learning through benign envy, or it may provoke social undermining through malicious envy. Therefore, on the one hand, managers can encourage temporary agency workers to compare themselves with excellent employees to promote self-improvement. On the other hand, managers should also be aware of the harm of malicious envy and take measures to prevent it. Managers can group employees based on job characteristics or skill level and set up excellent employees in each group to avoid excessive difficulty in employee advancement. Additionally, managers should ensure fairness in the system and transparency of information, including the criteria for excellent employees, and the resources and support that leaders can provide, to make it clear how employees can improve. Furthermore, managers can establish system red lines, raise the cost of social undermining to reduce such behavior and foster a harmonious and helpful team atmosphere, hold experience-sharing sessions for excellent employees, etc., to reduce the occurrence of malicious envy and undermining behavior.

Third, research by Dickerson et al demonstrated that positive emotional training can successfully reduce aggressive behavior.65 To reduce the painful experience of envy and undermining behavior,37 managers can provide emotion management training to improve employees’ emotional management capabilities. This will help employees learn to detect, understand and express emotions, release psychological pressure and negative emotions in an appropriate way, master positive emotional management and adaptation strategies, maintain a positive and optimistic mentality, and respond positively to upward social comparison.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, although this study collected a large sample size of 882, all data came from self-reports, potentially leading to social desirability bias, such as employees possibly reporting lower scores on social undermining than their true feelings. Future research could improve information technology and database construction in temporary staffing firms to support multi-source data collection methods. Also, questionnaire survey also has limitations in verifying the causal relationship between variables. Future research can be further improved by designing experiments.

Second, this study examined the mediating roles of benign and malicious envy in the relationship between upward social comparison and behavior choices. Although benign envy can induce informal workplace learning, envy is fundamentally a painful emotional experience, and benign envy and malicious envy both contain feelings of inferiority and frustration.63 Therefore, it is worth exploring whether upward social comparison can influence behavior through positive emotions such as admiration and which theories can be used to explain this. Future research could expand the mediating variables in the influence of upward social comparison on employee behavior choices to further enrich the field.

Third, this study posits that psychological availability is a boundary condition in the relationship between upward social comparison and envy. Future studies could further test other potential moderating factors. The cognitive appraisal theory of emotion suggests that individuals with different personal characteristics have different cognitive appraisals of environmental events. Hence, future studies could examine the moderating effects of variables such as achievement goal orientation, learning goal orientation, and openness to experience. In addition, this study was limited to the individual level. Future studies could incorporate organizational-level variables such as leadership style, and team atmosphere, for example, exploring the effects of differential leadership, differentiated empowering leadership, power distance, relational energy with colleagues or leaders, and so on. This would further expand the boundary mechanisms of the impact of upward social comparison on employee behavior.

Conclusion

The results show that the upward social comparison of temporary agency workers will produce both benign and malicious envy, which will lead to informal workplace learning and social undermining. Psychological availability can enhance benign envy and weaken malicious envy, and thus affect coping behavior. Enterprises should pay more attention to temporary agency workers and take effective measures to improve their psychological availability, so as to make full use of human capital and achieve win-win situation between the organization and temporary agency workers.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Our study was approved by the Science and Technology Ethics Committee of Shanghai University. All participation was voluntary, and the informed consent was obtained from them. Our Study followed the principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This study was supported by Shanghai Educational Science Research Project of China (Project No. C2022012).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Wilkin CL. I can’t get no job satisfaction: meta-analysis comparing permanent and contingent workers. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(1):47–64. doi:10.1002/job.1790

2. Guillaume P, Sullivan SE, Wolff H-G, Forret M. Are there major differences in the attitudes and service quality of standard and seasonal employees? An empirical examination and implications for practice. Hum Resour Manage. 2019;58(1):45–56. doi:10.1002/hrm.21929

3. Huenefeld L, Gerstenberg S, Hueffmeier J. Job satisfaction and mental health of temporary agency workers in Europe: a systematic review and research agenda. Work Stress. 2020;34(1):82–110. doi:10.1080/02678373.2019.1567619

4. Boyce AS, Ryan AM, Imus AL, Morgeson FP. ”Temporary worker, permanent loser?” A model of the stigmatization of temporary workers. J Manage. 2007;33(1):5–29. doi:10.1177/0149206306296575

5. Alamgir F, Cairns G. Economic inequality of the badli workers of Bangladesh: contested entitlements and a “perpetually temporary’ life-world. Hum Relat. 2015;68(7):1131–1153. doi:10.1177/0018726714559433

6. Chen C-A, Brudney JL. A cross-sector comparison of using nonstandard workers explaining use and impacts on the employment relationship. Admin Soc. 2009;41(3):313–339. doi:10.1177/0095399709334644

7. Latif K, Weng Q, Pitafi AH, et al. Social comparison as a double-edged sword on social media: the role of envy type and online social identity. Telemat Inform. 2021;56:101470. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2020.101470

8. Schmuck D, Karsay K, Matthes J, Stevic A. ”Looking Up and Feeling Down”. The influence of mobile social networking site use on upward social comparison, self-esteem, and well-being of adult smartphone users. Telemat Inform. 2019;42:101240. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101240

9. Seo M, Hyun KD. The effects of following celebrities’ lives via SNSs on life satisfaction: the palliative function of system justification and the moderating role of materialism. New Media Soc. 2018;20(9):3479–3497. doi:10.1177/1461444817750002

10. Brown DJ, Ferris DL, Heller D, Keeping LM. Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2007;102(1):59–75. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.10.003

11. Greenberg J, Ashton-James CE, Ashkanasy NM. Social comparison processes in organizations. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2007;102(1):22–41. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.006

12. Blader SL, Wiesenfeld BM, Fortin M, Wheeler-Smith SL. Fairness lies in the heart of the beholder: how the social emotions of third parties influence reactions to injustice. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2013;121(1):62–80. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.12.004

13. Lazarus RS. Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991.

14. Spence JR, Ferris DL, Brown DJ, Heller D. Understanding daily citizenship behaviors: a social comparison perspective. J Organ Behav. 2011;32(4):547–571. doi:10.1002/job.738

15. Li Y. Upward social comparison and depression in social network settings: the roles of envy and self-efficacy. Internet Res. 2019;29(1):46–59. doi:10.1108/IntR-09-2017-0358

16. van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Leveling up and down: the experiences of benign and malicious envy. Emotion. 2009;9(3):419–429. doi:10.1037/a0015669

17. Clarke N. HRD and the challenges of assessing learning in the workplace. Int J Train Dev. 2004;8(2):140–156. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2004.00203.x

18. Cross J. Informal Learning: Rediscovering the Natural Pathways That Inspire Innovation and Performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

19. Duffy MK, Ganster DC, Pagon M. Social undermining in the workplace. Acad Manage J. 2002;45(2):331–351. doi:10.2307/3069350

20. Kahn WA. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manage J. 1990;33(4):692–724. doi:10.5465/256287

21. Kulik CT, Ambrose ML. Personal and situational determinants of referent choice. Acad Manage Rev. 1992;17(2):212–237. doi:10.2307/258771

22. Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7(2):117–140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202

23. De Cuyper N, de Jong J, De Witte H, Isaksson K, Rigotti T, Schalk R. Literature review of theory and research on the psychological impact of temporary employment: towards a conceptual model. Int J Manag Rev. 2008;10(1):25–51. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00221.x

24. Wood JV. What is social comparison and how should we study it? Pers Soc Psychol B. 1996;22(5):520–537. doi:10.1177/0146167296225009

25. Foote DA. Temporary workers: managing the problem of unscheduled turnover. Manage Decis. 2004;42(8):963–973. doi:10.1108/00251740410555452

26. Collins RL. For better or worse: the impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(1):51–69. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

27. Parrott WG, Smith RH. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(6):906–920. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.906

28. Dvash J, Gilam G, Ben-Ze’ev A, Hendler T, Shamay-Tsoory SG. The envious brain: the neural basis of social comparison. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(11):1741–1750. doi:10.1002/hbm.20972

29. Walker DM. Luxury fever: why money fails to satisfy in an era of excess. South Econ J. 1999;66(1):199–200. doi:10.2307/1060848

30. Salerno A, Laran J, Janiszewski C, Dahl DW, Price LL, Lamberton C. The bad can be good: when benign and malicious envy motivate goal pursuit. J Consum Res. 2019;46(2):388–405. doi:10.1093/jcr/ucy077

31. Crusius J, Lange J. What catches the envious eye? Attentional biases within malicious and benign envy. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;55:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2014.05.007

32. Van de Ven N. Envy and its consequences: why it is useful to distinguish between benign and malicious envy. Soc Personal Psychol. 2016;10(6):337–349. doi:10.1111/spc3.12253

33. Noe RA, Clarke ADM, Klein HJ. Learning in the twenty-first-century workplace. Annu Rev Organ Psych. 2014;1(1):245–275. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091321

34. Schulz M, Rossnagel CS. Informal workplace learning: an exploration of age differences in learning competence. Learn Instr. 2010;20(5):383–399. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.03.003

35. Tesser A, Millar M, Moore J. Some affective consequences of social comparison and reflection processes: the pain and pleasure of being close. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(1):49–61. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.49

36. van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Appraisal patterns of envy and related emotions. Motiv Emotion. 2012;36(2):195–204. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9235-8

37. Tai K, Narayanan J, McAllister DJ. Envy as pain: rethinking the nature of envy and its implications for employees and organizations. Acad Manage Rev. 2012;37(1):107–129. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.0484

38. van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Why envy outperforms admiration. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2011;37(6):784–795. doi:10.1177/0146167211400421

39. van Dijk WW, Ouwerkerk JW, Goslinga S, Nieweg M, Gallucci M. When people fall from grace: reconsidering the role of envy in Schadenfreude. Emotion. 2006;6(1):156–160. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.1.156

40. Cohen-Charash Y, Mueller JS. Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy? J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):666–680. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.666

41. Broschak JP, Davis-Blake A. Mixing standard work and nonstandard deals: the consequences of heterogeneity in employment arrangements. Acad Manage J. 2006;49(2):371–393. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.20786085

42. Choi TR, Choi JH, Sung Y. I hope to protect myself from the threat: the impact of self-threat on prevention-versus promotion-focused hope. J Bus Res. 2019;99:481–489. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.010

43. Park LE, Maner JK. Does self-threat promote social connection? The role of self-esteem and contingencies of self-worth. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(1):203. doi:10.1037/a0013933

44. May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psych. 2004;77:11–37. doi:10.1348/096317904322915892

45. Russo M, Shteigman A, Carmeli A. Workplace and family support and work-life balance: implications for individual psychological availability and energy at work. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(2):173–188. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1025424

46. Binyamin G, Carmeli A. Does structuring of human resource management processes enhance employee creativity? The mediating role of psychological availability. Hum Resour Manage. 2010;49(6):999–1024. doi:10.1002/hrm.20397

47. Qian J, Zhang W, Qu Y, Wang B, Chen M. The enactment of knowledge sharing: the roles of psychological availability and team psychological safety climate. Front Psychol. 2020;11:551366. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551366

48. Halbesleben JRB, Wheeler AR. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress. 2008;22(3):242–256. doi:10.1080/02678370802383962

49. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J Occup Organ Psych. 2011;84(1):116–122. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

50. Gibbons FX, Buunk BP. Individual differences in social comparison: development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(1):129. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.129

51. Lange J, Crusius J. Dispositional Envy revisited: unraveling the motivational dynamics of Benign and Malicious Envy. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2015;41(2):284–294. doi:10.1177/0146167214564959

52. Decius J, Schaper N, Seifert A. Informal workplace learning: development and validation of a measure. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2019;30(4):495–535. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21368

53. Duffy MK, Ganster DC, Shaw JD, Johnson JL, Pagon M. The social context of undermining behavior at work. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2006;101(1):105–126. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.04.005

54. Lakey B, Cassady PB. Cognitive processes in perceived social support. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(2):337. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.2.337

55. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

56. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. New York: Sage; 1991.

57. Bonet R, Elvira MM, Visintin S. Hiring temps but losing perms? The effects of temporary hiring on turnover in a dual labor market. Acad Manage. 2020;17035. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2020.17035abstract

58. Davis-Blake A, Broschak JP, George E. Happy together? How using nonstandard workers affects exit, voice, and loyalty among standard employees. Acad Manage J. 2003;46(4):475–485. doi:10.5465/30040639

59. Khan MH, Noor A. Does employee envy trigger the positive outcomes at workplace? A study of upward social comparison, envy and employee performance. J Glob Bus Insights. 2020;5(2):169–188. doi:10.5038/2640-6489.5.2.1130

60. Smith RH. Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons. In: Suls J, editor. Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000:173–200.

61. Park J, Kim B, Park S. Understanding the behavioral consequences of upward social comparison on social networking sites: the mediating role of emotions. Sustainability. 2021;13(11):5781. doi:10.3390/su13115781

62. Crusius LJ. How do people respond to threatened social status? Moderators of Benign versus Malicious Envy. In: Smith RH, editor. Envy at Work and in Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

63. Sterling CM, van de Ven N, Smith RH. The two faces of envy: studying benign and malicious envy in the workplace. In: Smith RH, editor. Envy at Work and in Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016:57–84.

64. Feather NT. Deservingness and emotions: applying the structural model of deservingness to the analysis of affective reactions to outcomes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2006;17(1):38–73. doi:10.1080/10463280600662321

65. Dickerson KL, Skeem JL, Montoya L, Quas JA. Using positive emotion training with maltreated youths to reduce anger bias and physical aggression. Clin Psychol Sci. 2020;8(4):773–787. doi:10.1177/2167702620902118

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.