Back to Journals » Vascular Health and Risk Management » Volume 19

Comparison Between First-Ever Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults in 1988–1997 and 2008–2017

Authors Farah M, Næss H, Waje-Andreassen U, Nawaz B, Fromm A

Received 8 December 2022

Accepted for publication 30 March 2023

Published 14 April 2023 Volume 2023:19 Pages 231—235

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S398127

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Daniel Duprez

Mohamad Farah, Halvor Næss, Ulrike Waje-Andreassen, Beenish Nawaz, Annette Fromm

Neurology Department, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway

Correspondence: Mohamad Farah, Email [email protected]

Aim: To compare incidence of first-ever acute cerebral infarction, etiology and traditional risk factors in young adults 15– 49 years in 1988– 1997 and 2008– 2017 in Hordaland County, Norway.

Methods: Case-finding of young adults with acute cerebral infarction in 1988– 1997 was done retrospectively by computer research from hospital registries in Hordaland County. Young adults with acute cerebral infarction living in the Bergen region in 2008– 2017 were prospectively included in a database at Haukeland University Hospital. Traditional risk factors, etiology and modified Rankin scale score on discharge were registered.

Results: Crude average incidence of acute cerebral infarction was 11.4 per 100.000 per year in 1988– 1997 and 13.2 per 100.000 per year in 2008– 2017 (P=0.04). The prevalence of prior myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and dyslipidemia were lower in the 2008– 2017 cohort (all P< 0.05). Atherosclerosis was less common in the 2008– 2017 cohort (P< 0.001).

Conclusion: The observed incidence of acute cerebral infarction in young adults increased from 1988– 1997 to 2008– 2017 in Hordaland County. Atherosclerosis was less common in the 2008– 2017 cohort.

Keywords: young stroke, incidence, acute ischemic stroke, public health

Introduction

According to some studies, the incidence and prevalence of traditional risk factors in young adults with acute cerebral infarction have increased in recent years.1–8 Possible causes for increased incidence are an increased prevalence of risk factors and illicit drug use in the general population.1,2,9 However, higher awareness of stroke symptoms and introduction of MRI may also have contributed to higher incidence.

We previously performed a population-based study of first–ever acute cerebral infarction in young adults in Hordaland County in Norway between 1988 and 1997.10,11 Since 2006 we have prospectively included all stroke patients admitted to Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, in a stroke registry.

In this paper, we present a comparison between patients from the 1988–1997 cohort and patients admitted 2008–2017 (15–49 years). We hypothesized that the incidence of first-ever acute cerebral infarction was higher in the 2008–2017 cohort.

Methods

Acute cerebral infarction was defined in accordance with the Baltimore-Washington Cooperative Young Stroke Study Criteria comprising neurological deficits lasting more than 24 h because of ischemic lesions or transient ischemic attacks where CT or MRI showed infarctions related to the clinical findings.12

1988–1997 Cohort

All hospitalized patients 15–49 years old with first-ever cerebral infarction from 1988 to 1997 living in Hordaland County were included. Case-finding was done retrospectively by computer search from hospital registries in Hordaland County as described previously.10 More than 90% of the patients were admitted to Haukeland University Hospital. The mean population in Hordaland County was 201,703 per year.

Determination of etiology as determined by the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification,13 registration of traditional risk factors and modified Rankin scale (mRs) score on discharge were based on the patient record.

2008–2017 Cohort

All consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke (the index stroke) admitted to the Center for Neurovascular Diseases, Department of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital since February 2006 were prospectively registered in a database (The Bergen NORSTROKE Registry). In this study, we included patients 15–49 years of age with first-ever cerebral infarction admitted 2008–2017 and living in the Bergen region. The Bergen region is a well-defined geographical subregion of Hordaland County. The mean population was 197,658 per year.

Etiology was determined by the TOAST criteria.13 Risk factors were defined according to a predefined protocol: myocardial infarction, peripheral atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking.

mRS score was obtained day 7 or on discharge if discharged before day 7.

Risk Factors

In both cohorts, current smoking was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day. Diabetes mellitus was considered present if the patient was on a glucose-lowering diet or medication. Hypertension, myocardial infarction, and peripheral artery disease were considered present if diagnosed by a physician any time before stroke onset. Dyslipidemia was defined as use of statin before the index stroke or cholesterol >6.5 mmol/l during the hospital stay for the index stroke.

Investigations included CT, MRI, angiography (CT or MRI), echocardiography, Holter monitoring (usually 24 h), ECG, and duplex sonography of neck vessels. However, in the 1988–1997 cohort, MRI, echocardiography, Holter monitoring, and angiography (CT or MRI) were less frequently used.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and is approved by the local ethics committee (REK Vest). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Statistics

This study is an incidence-based population study. Incidence calculation in 1988–1997 has been described previously.10 Incidence calculation in the 2008–2017 cohort was based on the number of first-ever cerebral infarctions and the population in the Bergen region for the 2008–2017 cohort. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated on the basis of the Poisson distribution. Student’s t-test and chi-square were used when appropriate. STATA 15.0 (StataCorp 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77,845 USA) was used for analyses.

Results

The number of patients was 232 in the 1988–1997 cohort and 261 in the 2008–2017 cohort. The average crude incidence in Hordaland County for acute cerebral infarction was 11.4 per 100,000 in the 1988–1997 interval and 13.2 per 100,000 in the 2008–2017 interval (P=0.04) (Table 1). There were no differences in the incidence rates for females (P=0.25) or males (P=0.10) between the two cohorts. Within both cohorts, the incidence rates were higher for males than for females (P=0.03 in the 1988–1997 cohort and P=0.01 in the 2008–2017 cohort) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Average Incidence per 100.000 per Year of Acute Cerebral Infarction in Patients Aged 15–49 in Hordaland County |

Among patients in the previous cohort <30 years 7 (30%) patients were males and 16 (70%) were females and among patients ≥30 years 129 (62%) were males and 80 (38%) were females (P=0.004). Among patients in the current cohort <30 years 14 (44%) patients were males and 18 (56%) were females and among patients ≥30 years 141 (62%) were males and 88 (38%) were females (P=0.05). The sex proportion differences between the cohort were significant (P=0.04). The proportion of patients <30 years in the previous cohort did not differ from the corresponding proportion in the current cohort (9.9% versus 12.2%, P=0.41).

Table 2 shows the frequencies of risk factors in the two cohorts. Myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and dyslipidemia were less frequent in the 2008–2017 cohort (all P≤.05).

|

Table 2 Risk Factors in Young Ischemic Stroke Patients in 1988–1997 and 2008–2017 |

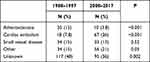

Table 3 shows the etiologies in the two cohorts. Atherosclerosis was less frequent, whereas cardiac embolism and other causes were more frequent in the 2008–2017 cohort. Major cardiac sources comprised 10 (3.8%) patients and minor sources (including patent foramen ovale (n=47) or atrial septum aneurysm (n=7)) comprised 57 (21.8%) patients in the current cohort. Among patients with unknown etiology 69 (26.4%) had cryptogenic cerebral infarction and 26 (10.0%) had competing causes in the 2008–2017 cohort.

|

Table 3 Etiology (TOAST) in 1988–1997 versus 2008–2017 |

On discharge 186 (80%) in the previous cohort and 211 (81%) in the current cohort had mRS 0–2 (P=0.85). Eight (3.4%) patients in the previous cohort and 7 (2.7%) patients in the current cohort died during the hospital stay (P=0.62). All patients in both cohorts died because of a large infarction.

In the 2008–2017 cohort, 255 (98%) patients underwent MRI including diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and 31 (12%) patients had DWI lesions on MRI, but recovered within 24 h. In the previous cohort, 71 (31%) patients underwent MRI. None included DWI.

Discussion

We confirmed our hypothesis that the observed incidence of cerebral infarction in young adults increased from 1988–1997 to 2008–2017. Thus, our result is in accord with several other studies that have shown an increased incidence in recent years.1,3,7,8 A study including all stroke patients aged 15–54 years in Norway showed a weak decline in incidence rate of ischemic stroke between 2010 and 2015.14

In contrast to some other studies, the frequencies of traditional risk factor did not increase.2 The frequencies of hypertension, smoking, and diabetes mellitus remained unchanged, whereas the frequencies of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and dyslipidemia decreased significantly. This is consistent with a decreasing incidence of myocardial infarction in Norway's general population in recent years.15

The difference between our study and other studies may be due to different methodologies. Our study was based on patient records and patient interviews, whereas other studies used administrative data. Administrative data are likely less reliable.

The frequencies of risk factors differ between young and old ischemic stroke patients. Comparing ischemic stroke patients younger and older than 50 years of age in Hordaland County, Norway, showed that coronary heart disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and diabetes mellitus were significantly more frequent among older patients.16

Investigations were more thorough in the current cohort compared to the previous cohort. Almost all underwent DWI in the 2008–2017 cohort. DWI is sensitive to small acute cerebral infarction, and this may explain that 13% of the patients in the current cohort recovered within 24 h. It is unlikely that the majority of similar patients would have been included in the 1988–1997 cohort where none had DWI and patients with TIA and normal CT or MRI were excluded.

One might expect the reduction in traditional risk factors to decrease in the general population, and the use of DWI to increase the observed incidence of acute cerebral infarction. Furthermore, the general awareness of stroke symptoms has increased in recent years because of new treatment options such as thrombolysis and thrombectomy. This has probably reduced the threshold for seeking medical help among patients with minor symptoms as perceived by patients or emergency doctors outside the hospital, leading to the hospitalization of more patients with acute cerebral infarction.17 On balance, reduced frequencies of risk factors, use of DWI, better awareness of stroke symptoms and treatment options and little change in observed incidence rates suggest that the true incidence of acute cerebral infarction in young adults may have decreased in Hordaland County between 1988–1997 and 2008–2017.

The most important difference as to etiology was the significant reduction of atherosclerosis in the 2008–2017 cohort. This is compatible with the low frequencies of coronary heart disease and peripheral atherosclerosis in the current cohort compared with the previous cohort.

The differences as to cardiac embolism, other etiologies, and unknown etiology are likely due to more comprehensive investigations in the 2008–2017 cohort. Angiography (MRI or CT) was frequently used in the 2008–2017 cohort, probably disclosing more patients with dissection of neck vessels. Transesophageal echocardiography disclosed patent foramen ovale in many patients with an embolic stroke of otherwise unknown etiology in the 2008–2017 cohort.

A limitation of the present study is that inclusion of patients in 1988–1997 was retrospective and possibly underestimated the frequencies of risk factors. In contrast, the 2008–2017 cohort was included prospectively. Etiologies and risk factors were systematically registered in both cohorts. However, in the 1988–1997 cohort, MRI, echocardiography, Holter monitoring, and angiography (CT or MRI) were less frequently used. A strength of the study is the comparison of two cohorts admitted to the same hospital. In both periods, the threshold for admitting patients with possible acute stroke to our hospital was low. Another strength of the study is that patient data were based on patient records and patient interviews and not on administrative data, which has been the most common method in other studies.6–8

In conclusion, the observed incidence of acute cerebral infarction in young adults increased from 1988–1997 to 2008–2017 in Hordaland County. Atherosclerosis was less common in the 2008–2017 cohort.

Funding

This research was funded by Evjen Fund, Western Norway, which had no influence on the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Alwell K, et al. Age at stroke: temporal trends in stroke incidence in a large, biracial population. Neurology. 2012;79(17):1781–1787. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318270401d

2. George MG, Tong X, Kuklina EV, Labarthe DR. Trends in stroke hospitalizations and associated risk factors among children and young adults, 1995–2008. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(5):713–721. doi:10.1002/ana.22539

3. Bejot Y, Daubail B, Jacquin A, et al. Trends in the incidence of ischaemic stroke in young adults between 1985 and 2011: the Dijon Stroke Registry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(5):509–513. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-306203

4. Krishnamurthi RV, Moran AE, Feigin VL, et al. Stroke prevalence, mortality and disability-adjusted life years in adults aged 20–64 years in 1990–2013: data from the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):190–202. doi:10.1159/000441098

5. Lee LK, Bateman BT, Wang S, Schumacher HC, Pile-Spellman J, Saposnik G. Trends in the hospitalization of ischemic stroke in the United States, 1998–2007. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(3):195–201. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00700.x

6. Ramirez L, Kim-Tenser MA, Sanossian N, et al. Trends in acute ischemic stroke hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:5.

7. Rosengren A, Giang KW, Lappas G, Jern C, Toren K, Bjorck L. Twenty-four-year trends in the incidence of ischemic stroke in Sweden from 1987 to 2010. Stroke. 2013;44(9):2388–2393. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001170

8. Tibaek M, Dehlendorff C, Jorgensen HS, Forchhammer HB, Johnsen SP, Kammersgaard LP. Increasing incidence of hospitalization for stroke and transient ischemic attack in young adults: a Registry-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:5. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.003158

9. de Los Rios F, Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, et al. Trends in substance abuse preceding stroke among young adults: a population-based study. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3179–3183. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.667808

10. Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L, Aarseth J, Nyland G, Myhr KM. Incidence and short-term outcome of cerebral infarction in young adults in western Norway. Stroke. 2002;33(8):2105–2108. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000023888.43488.10

11. Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L, Aarseth J, Myhr KM. Etiology of and risk factors for cerebral infarction in young adults in western Norway: a population-based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11(1):25–30. doi:10.1046/j.1351-5101.2003.00700.x

12. Johnson CJ, Kittner SJ, McCarter RJ, et al. Interrater reliability of an etiologic classification of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1995;26(1):46–51. doi:10.1161/01.STR.26.1.46

13. Adams HP

14. Barra M, Labberton AS, Faiz KW, et al. Stroke incidence in the young: evidence from a Norwegian register study. J Neurol. 2019;266(1):68–84. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-9102-6

15. Folkehelseinstituttet [Norwegian Institute of Public Health]. Hjerte- og karsykdommer i Norge [Cardiovascular disease in Norway]; 2019. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/hin/ikke-smittsomme/Hjerte-kar/.

16. Fromm A, Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Naess H. Comparison between ischemic stroke patients <50 years and >/=50 years admitted to a single centre: the Bergen stroke study. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:183256. doi:10.4061/2011/183256

17. Advani R, Naess H, Kurz M. Mass media intervention in Western Norway aimed at improving public recognition of stroke, emergency response, and acute treatment. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(6):1467–1472. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.02.026

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.