Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 12

Combined application of tenuigenin and β-asarone improved the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease

Received 30 October 2017

Accepted for publication 8 December 2017

Published 5 March 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 455—462

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S155567

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Tuo Deng

Wenguang Chang,1 Junfang Teng2

1Department of Neurology, Xinxiang Central Hospital, Xinxiang, Henan, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Henan, People’s Republic of China

Background: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease which cannot be cured at present. The aim of this study was to assess whether the combined application of β-asarone and tenuigenin could improve the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD.

Patients and methods: One hundred and fifty-two patients with moderate-to-severe AD were recruited and assigned to two groups. Patients in the experiment group received β-asarone 10 mg/d, tenuigenin 10 mg/d, and memantine 5–20 mg/d. Patients in the control group only received memantine 5–20 mg/d. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) were used to assess the therapeutic effects. The drug-related adverse events were used to assess the safety and acceptability. Treatment was continued for 12 weeks.

Results: After 12 weeks of treatment, the average MMSE scores, ADL scores, and CDR scores in the two groups were significantly improved. But, compared to the control group, the experimental group had a significantly higher average MMSE score (p<0.00001), lower average ADL score (p=0.00002), and lower average CDR score (p=0.030). Meanwhile, the rates of adverse events were similar between the two groups. Subgroup analysis indicated that the most likely candidates to benefit from this novel method might be the 60–74-years-old male patients with moderate AD.

Conclusion: These results demonstrated that the combined application of β-asarone and tenuigenin could improve the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD. The clinical applicability of this novel method showed greater promise and should be further explored.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, memantine, β-asarone, tenuigenin

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease which is characterized by progressive impairment of cognitive function. Globally, dementia affected about 46 million people in 2015,1 and it is projected to affect about 100 million people worldwide by 2050.2 In recent decades, due to the aging population, the number of AD patients is expected to significantly increase.3 It most often begins in people aged ≥65 years, and could affect about 6% of these people.4 Meanwhile, AD is the most common cause of dementia in the worldwide, and dementia often results in the death of AD patients.5 In developed countries, AD has become one of the most financially costly diseases. The huge financial burden of AD could severely affect the quality of life of AD patients, and even the social development.6,7

Nowadays, four acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and tacrine) and one NMDA receptor antagonist (memantine) have been recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat AD. These drugs mainly provide limited short-term treatment of AD symptoms.8 The AChEIs could only yield modest symptomatic but not curative effects9 and have considerable drug-related adverse events.10 Memantine represents a new treatment method for AD and is approved for treating moderate-to-severe AD. It acts on the glutamatergic system by blocking NMDA receptors and inhibiting their overstimulation by glutamate.11 Memantine has infrequent and mild drug-related adverse events, including hallucinations, fatigue, and headache. A previous study showed that the combination of memantine and cholinesterase inhibitors yielded a statistically significant but clinically marginal improvement in cognitive function and global assessment of dementia.12 However, most of the current treatment methods could only offer some symptomatic relief. Therefore, novel treatment methods are urgently needed.

A previous study reported that the β-asarone had a good effect in cognitive function by suppressing the neuronal apoptosis.13 Inhibiting the increase of intracellular calcium concentration in damaged neurons might be the mechanism of its protective effect against neuronal apoptosis.14 Meanwhile, Irie and Keung15 found that the β-asarone could protect PC-12 cells from the cytotoxic action of Aβ1–40 by inhibiting basal Ca(2+) intake. Junhe et al16 found that the β-asarone had a role in the inhibition of Aβ peptide neurotoxicity. Our previous study showed that β-asarone could prevent the Aβ25-35-induced inflammatory responses and autophagy.17 These results indicated that β-asarone might play the role of an antidementia medication mainly by the inhibition of β-amyloid protein aggregation and the protection of neurons.18 In addition, an animal study showed that the tenuigenin could improve the learning and memory function of rats with Aβ1–40-induced AD by regulating the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, blocking Cyt-c release, and reducing caspase-3 expression.19 Another study found that tenuigenin could block the endogenous pathway of PC12 cell apoptosis by inhibiting Bax and Cyt-c expression and increasing Bcl-2 expression.20

These previous findings indicated that the β-asarone and tenuigenin had different mechanisms of action. But the archives of traditional Chinese medicine showed that the acorus gramineus, whose main active ingredient was β-asarone, and tenuigenin were often used together as augmentations to treating AD,21 which might indicate that the β-asarone and tenuigenin had a synergistic effect in treating AD. However, because of the lack of enough data, the current evidence is still not enough to demonstrate the add-on effects of the combination application of β-asarone and tenuigenin in treating AD. Therefore, this study was conducted to further evaluate the add-on effects of the combination application of β-asarone and tenuigenin as an adjuvant therapy for memantine in treating AD patients.

Patients and methods

Patient recruitment

This study was reviewed and approved by the boards and ethics committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Patients with moderate-to-severe AD were recruited by two experienced clinicians according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria included the following: 1) AD being diagnosed using Neurological Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association guidelines; 2) AD patients aged 60–85 years; 3) magnetic resonance imaging or cranial computed tomography showing brain atrophy (medial temporal lobe volume or hippocampus); 4) Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy Rating Scale score ≥2 for patients aged 60–74 years and ≥3 for patients aged 75–85 years; and 5) Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) score of 2 (moderate AD) or 3 (severe AD). Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria included: 1) dementia caused by other factors, such as frontotemporal dementia, hypothyroidism, and metabolic abnormalities; 2) presence of a serious heart condition, renal system disease, hepatic disease, or hematopoietic system disease; and 3) allergy to memantine or possessing an allergic physique. Written informed consents were provided by the included patients or their family members for treatment and to be included in our study. The study was conducted between September 2014 and September 2017.

Intervention methods

The recruited AD patients were assigned to two groups. In the experiment group, memantine 5 mg was given once daily in the morning on the first week. In the second week, memantine 5 mg was given both in the morning and in the afternoon. During the third week, memantine 10 and 5 mg were given in the morning and afternoon, respectively. During the 4th–12th week, memantine 10 mg was given both in the morning and in the afternoon. Meanwhile, patients also received β-asarone 10 mg/d and tenuigenin 10 mg/d during the whole treatment period. In the control group, patients only received memantine using the same administration method as for the experiment group. The treatment was continued for 12 weeks. The treatment was terminated if severe drug-related adverse events occurred. The patients were not blinded to the treatment methods, but the investigators and data analysts were blinded.

Outcome assessment

Although the efficacy could be comprehensively evaluated using many scales, it does not mean “more is better.” That is because more testing time is needed when using more scales, which could easily cause fatigue of patients and then result in the increased false-negative rate.22,23 Therefore, we only selected three main scales to evaluate the efficacy of the two intervention methods in this study. The cognitive function of AD patients was evaluated using Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scale. The daily living ability of AD patients was evaluated using Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale. The global clinical assessment was evaluated using the CDR scale. Meanwhile, the drug-related adverse events were also recorded during the whole treatment period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented by mean and standard deviation, and dichotomous data are presented as number and percentage. The independent Student’s t-test and χ2 test were used when appropriate. For the purpose of covarying out the effect of initial values, the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine the effect of the two intervention methods on the MMSE, ADL, and CDR scores at the last assessment.24 Also, subgroup analysis was conducted according to the severity of dementia, age, and sex. All tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients with AD

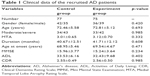

Totally, 152 AD patients were recruited and assigned to the control (n=77) and experiment (n=75) groups. The two groups had similar average ages, Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy Rating Scale score, duration, and age at onset. There were 34 moderate and 43 severe AD patients in the control group, and 33 moderate and 42 severe AD patients in the experiment group. Before treatment, the average MMSE scores, ADL scores, and CDR scores were comparable between the two groups. Detailed information is presented in Table 1. Eight and six patients in the control and experiment groups, respectively, did not complete the trial. The reasons included: 1) patents or family members requesting for another treatment method; 2) patents or family members abandoning treatment; 3) patents or family members unable to afford the cost; and 4) patents or family members thinking that the condition had improved enough to stop the treatment.

Cognitive function

Before the treatment, the average MMSE scores between the control and experiment groups were nonsignificantly different (p=0.234). After 12 weeks of treatment, compared to their initial values, the average MMSE scores were significantly increased to 19.36±3.64 (p<0.00001) in the control group and 22.79±3.18 (p<0.00001) in the experiment group. However, the result of ANCOVA showed that the average MMSE score in the experiment group was significantly higher compared to the control group (p<0.00001, Figure 1). These results demonstrated that the combination of β-asarone and tenuigenin plus memantine could better improve the cognitive function of AD patients than memantine as monotherapy.

| Figure 1 MMSE scores before and after 12 weeks of treatment in the two groups. |

Daily living ability

Before the treatment, the average ADL scores between the control and experiment groups were nonsignificantly different (p=0.402). After 12 weeks of treatment, compared to their initial values, the average ADL scores were significantly decreased to 28.15±7.28 (p<0.00001) in the control group and 22.87±7.27 (p<0.00001) in the experiment group. However, the result of ANCOVA showed that the average ADL score in the experiment group was significantly higher compared to the control group (p=0.00002, Figure 2). These results demonstrated that the combination of β-asarone and tenuigenin plus memantine could better improve the daily living ability of AD patients than memantine as monotherapy.

| Figure 2 ADL scores before and after 12 weeks of treatment in the two groups. |

Global clinical assessment

Before the treatment, the average CDR scores between the control and experiment groups were nonsignificantly different (p=0.985). After 12 weeks of treatment, compared to their initial values, the average CDR scores were significantly decreased to 2.03±0.57 (p<0.00001) in the control group and 1.83±0.60 (p<0.00001) in the experiment group. However, the result of ANCOVA showed that the average CDR score in the experiment group was significantly higher compared to the control group (p=0.030, Figure 3). These results demonstrated that the combination of β-asarone and tenuigenin plus memantine could better improve the global clinical assessment of AD patients than memantine alone as monotherapy.

| Figure 3 CDR scores before and after 12 weeks of treatment in the two groups. |

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted according to the severity of dementia, age, and sex. With regard to cognitive function (Figure 4), after 12 weeks of treatment, compared to the moderate and severe AD patients in the control group, both the moderate and severe AD patients in the experiment group had significantly higher average MMSE scores (p<0.00001, p=0.0002, respectively, Figure 4A). Compared to the 60–74- and 75–85-years-old patients in the control group, both the age groups in the experiment group had significantly higher average MMSE scores (p=0.00005, p=0.00003, respectively, Figure 4B). When assessed with regard to sex, both the female and male patients in the experiment group had significantly higher average MMSE scores (p<0.00001, p=0.007, respectively, Figure 4C) than those in the control group.

With regard to daily living ability (Figure 5), after 12 weeks of treatment, compared to the moderate and severe AD patients in the control group, both the moderate and severe AD patients in the experiment group had significantly lower average ADL scores (p=0.0005, p=0.012, respectively, Figure 5A). When assessing in terms of the two age groups, both the age groups in the experiment group had significantly lower average ADL scores (p=0.008, p=0.001, respectively, Figure 5B) than the control group. When comparing based on patients’ sex, both the female and male patients in the experiment group had significantly lower average ADL scores (p=0.061, p=0.0003, respectively, Figure 5C) than the control group.

In terms of global clinical assessment (Figure 6), after 12 weeks of treatment, compared with the moderate and severe AD patients in the control group, the moderate AD patients, but not the severe AD patients, in the experiment group had a significantly lower average CDR score (p=0.042, Figure 6A). When compared with the two age groups in the control group, the 60–74-years-old patients, but not the 75–85-years-old patients, in the experiment group had a significantly lower average CDR score (p=0.003, Figure 6B). When comparing in terms of sex, the male, but not the female, patients in the experiment group had a significantly lower average CDR score (p=0.030, Figure 6C) than the patients of both sexes in the control group.

Drug-related adverse events

Ten patients in the control group experienced drug-related adverse events, including confusion, fatigue, hallucinations, and dizziness. Meanwhile, 12 patients in the experiment group experienced drug-related adverse events, including hallucinations, headache, nausea, and somnolence. These adverse events were mild and transient, and did not need any special treatment. In this study, we found that no one in the experiment group experienced hepatomas, teratogenicity, mutagenesis, and genotoxicity, although these adverse events could not be correctly identified in the short term.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the combination application of β-asarone and tenuigenin could improve the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD. After 12 weeks of treatment, compared with the control group, the experiment group had a significantly higher average MMSE score (p<0.00001), lower average ADL score (p=0.00002), and lower average CDR score (p=0.030). Moreover, the two groups had similar rates of drug-related adverse events. These results demonstrated that the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD was significantly improved after the addition of β-asarone and tenuigenin, and the acceptability of this novel method was good.

Meanwhile, through subgroup analysis, we found some interesting results. These were as follows: 1) this novel method could significantly improve the cognitive function of AD patients, irrespective of whether the patient had moderate or severe AD, was aged 60–74 or 75–85 years, and was female or male; 2) this novel method could not significantly improve the daily living ability of female AD patients; and 3) this novel method could only significantly alleviate the severity of dementia of moderate AD patients, aged 60–74-years-old AD patients, or male AD patients. These results indicated that this novel method might produce better efficacy for 60–74-years-old male patients with moderate AD than for other AD patients. However, as we were limited by the small samples in subgroup analysis, the most likely candidates to benefit from this novel method need verification in future studies.

Other novel treatment methods have also been developed to improve the efficacy of the recommended drugs. Peng et al25 reported that acupuncture could improve the cognitive function of AD patients, and another study is being conducted to further assess whether acupuncture could improve the efficacy of donepezil in treating AD.26 In addition, the combination of huperzine A and memantine was found to be an optimal choice in treating AD.27 Feng et al28 reported that nimodipine might be an effective augmentation for memantine in treating AD. Although so many works have been done, there is still no clinically approved disease-modifying therapy for AD. Our findings offer a potentially effective novel treatment method for clinicians in treating AD.

Although many studies have been done, there is still no cure for AD. The current treatments can be divided into three types: pharmaceutical, psychosocial, and caregiving. The medications mainly refer to AChEI and NMDA receptor antagonists, which are currently used to treat the cognitive problems of AD. The psychosocial interventions can be classified as cognition-, behavior-, emotion-, or stimulation-oriented approaches, and these are usually used as adjunct to pharmaceutical treatment. Since no cure or treatment has yet been found for AD, and AD could gradually render individuals incapable of tending to their own needs, caregiving is essentially the treatment. Therefore, it must be carefully managed during the course of AD.

As one of the most serious health problems for the older population, AD has been receiving more and more attention. Over the past several decades, in order to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in AD pathogenesis, researchers have done many studies. However, the cause of AD is still poorly understood. The unclear pathogenesis might be the main cause of the minimal benefit obtained due to the currently recommended drugs in the treatment of AD. Nowadays, there are several competing hypotheses that try to explain the cause of AD. These include the following: 1) genetic hypothesis, previous studies found that the genetic heritability of AD could range from 49% to 79%;29,30 2) cholinergic hypothesis, which suggests that AD is mainly caused by the reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine31 (most currently available drugs are based on this hypothesis); 3) amyloid hypothesis, which proposes that the extracellular amyloid beta deposits are the fundamental cause of AD;32 4) tau hypothesis, which postulates that tau protein abnormalities initiate the disease cascade;33 and 5) other hypotheses, such as neurovascular hypothesis34 and retrogenesis hypothesis.35 Recently, gut microbiota have been found to be involved in many neuropsychiatric disorders.36,37 Hu et al38 reported that there was a closely relationship between the imbalance of gut microbiota and AD. Therefore, the gut microbiota might provide a new mechanism to explain AD pathogenesis.

Several limitations in the present study should be noted. These are as follows: 1) All patients were from the same city, which might influence the applicability of this novel method.39 2) This was not a randomization study, and the intervention methods were not blinded to the patients. However, to minimize any bias from the two treatment methods, the investigators and data analysts were blinded. 3) This was the first study to explore whether the combined application of β-asarone and tenuigenin could improve the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD. Therefore, there is no previous study to help us choose the optimal doses of β-asarone and tenuigenin. The doses used in this study were selected according to a case report.40 4) Whether other doses of β-asarone and tenuigenin have similar effects or not was not assessed here. 5) We did not compare the effects of this novel method and only used β-asarone or tenuigenin plus memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD. 6) Although no hepatomas, mutagenesis, genotoxicity, and teratogenicity were identified in patients receiving β-asarone, future studies should consider the risk of these adverse events.41–43 7) This was a preliminary study, so the long-term effects of this novel method were not evaluated. Future large-scale, multicenter, randomized studies are needed to solve these limitations.

Conclusion

The combined application of β-asarone and tenuigenin could significantly improve the efficacy of memantine in treating moderate-to-severe AD, and the acceptability of this novel method was good. Moreover, we found that the most likely candidates to benefit from this novel method might be male AD patients aged 60–74 years with moderate disease. Our study offered a potentially effective novel treatment method for treating moderate-to-severe AD, whose clinical applicability showed greater promise and should be further explored.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81241046). We thank the nurses from the Department of Neurology for their help.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. | ||

Mucke L. Neuroscience: Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2009;461(7266):895–897. | ||

Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. | ||

Burns A, Iliffe S. Alzheimer’s disease. BMJ. 2009;338:b158. | ||

GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. | ||

Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. International global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–2117. | ||

Wimo A, Winblad B, Jonsson L. The worldwide societal costs of dementia: estimate for 2009. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:98–103. | ||

Klafki HW, Staufenbiel M, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J. Therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006;129:2840–2855. | ||

Atri A, Shaugnessy LW, Locascio JJ, Growdon JH. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:209–210. | ||

Hansen R, Gartlehner G, Webb PA. Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:211–255. | ||

Lipton SA. Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: memantine and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(2):160–170. | ||

Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379–397. | ||

Geng Y, Li C, Liu J, et al. Beta-asarone improves cognitive function by suppressing neuronal apoptosis in the beta-amyloid hippocampus injection rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33(5):836–843. | ||

Jiang Y, He Y, Zou Y, Fang Y. Effects of β-asarone on the variability of calcium levels in mice cortical neurons. Chin J Rehabil Med. 2007;22(6):490–491. | ||

Irie Y, Keung WM. Rhizoma acori graminei and its active principles protect PC-12 cells from the toxic effect of amyloid-beta peptide. Brain Res. 2003;963(1–2):282–289. | ||

Junhe G, Yunbo C, Gang W, et al. Effects of active components of Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii and their compatibility at different ratios on learning and memory abilities in dementia mice. Tradit Chin Drug Res Clin Pharmacol. 2012;23(2):114–117. | ||

Chang W, Teng J. β-Asarone prevents Aβ25-35-induced inflammatory responses and autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells: down expression Beclin-1, LC3B and up expression Bcl-2. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):20658–20663. | ||

Shuang X, Tan Z. Mechanism of action of Shichangpu on dementia. Henan Tradit Chin Med. 2016;36(4):720–721. | ||

Ye H, Chen Q. Protective effect of tenuigenin on impaired learning and memory in rats with Aβ1–40-induced AD. Chin J New Drugs. 2013;22(22):2674–2678. | ||

Yang X, Chen Q, Chen Q, Jin B, Ye H. Protection of tenuigenin against apoptosis of PC12 cells induced by amyloid beta-protein fragment 1–40. Chin J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;27(3):379–384. | ||

Yan J, Chen Y. Study on the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease by traditional Chinese medicine. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. 2008;26(7):1495–1496. | ||

Silverstein JH, Timberger M, Reich DL, Uysal S. Central nervous system dysfunction after noncardiac surgery and anesthesia in the elderly. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(3):622–628. | ||

Collie A, Darekar A, Weissgerber G, et al. Cognitive testing in early-phase clinical trials: development of a rapid computerized test battery and application in a simulated Phase I study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(4):391–400. | ||

Kang R, He Y, Yan Y, et al. Comparison of paroxetine and agomelatine in depressed type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1307–1311. | ||

Peng J, Luo L, Xu L, Chen X. Therapeutic efficacy observation on electroacupuncture for Alzheimer’s disease. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2015;13:171–174. | ||

Peng W, Zhou J, Xu M, Feng Q, Bin L, Liu Z. The effect of electroacupuncture combined with donepezil on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):301. | ||

Shao ZQ. Comparison of the efficacy of four cholinesterase inhibitors in combination with memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2944–2948. | ||

Feng W, Liu Y, Zhu H. Efficacy of the combination of nimodipine and memantine in treating Alzheimer’s disease. Tianjin Pharmacy. 2017;29(1):27–28. | ||

Wilson RS, Barral S, Lee JH, et al. Heritability of different forms of memory in the Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(2):249–255. | ||

Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):168–174. | ||

Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of progress. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(2):137–147. | ||

Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12(10):383–388. | ||

Mudher A, Lovestone S. Alzheimer’s disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands? Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(1):22–26. | ||

Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Role of the blood-brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):191–197. | ||

Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Hasan SM, et al. Retrogenesis: clinical, physiologic, and pathologic mechanisms in brain aging, Alzheimer’s and other dementing processes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249(Suppl 3):28–36. | ||

Chen JJ, Zeng BH, Li WW, et al. Effects of gut microbiota on the microRNA and mRNA expression in the hippocampus of mice. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322(Pt A):34–41. | ||

Fang X. Potential role of gut microbiota and tissue barriers in Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J Neurosci. 2016;126(9):771–776. | ||

Hu X, Wang T, Jin F. Alzheimer’s disease and gut microbiota. Sci China Life Sci. 2016;59(10):1006–1023. | ||

Chen JJ, Zhou CJ, Zheng P, et al. Differential urinary metabolites related with the severity of major depressive disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2017;332:280–287. | ||

Zheng M. Combined application of Shichangpu and Yuanzhisan in treating patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Tradit Chin Med. 2010;2:16–17. | ||

Haupenthal S, Berg K, Gründken M, et al. In vitro genotoxicity of carcinogenic asarone isomers. Food Funct. 2017;8(3):1227–1234. | ||

Unger P, Melzig MF. Comparative study of the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of alpha- and beta-asarone. Sci Pharm. 2012;80(3):663–668. | ||

Chellian R, Pandy V, Mohamed Z. Pharmacology and toxicology of α- and β-asarone: a review of preclinical evidence. Phytomedicine. 2017;32:41–58. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.