Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 8

Closure of a local public hospital in Korea: focusing on the organizational life cycle

Authors Yeo YH, Lee KH , Kim HJ

Received 18 May 2016

Accepted for publication 10 August 2016

Published 11 November 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 95—105

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S113070

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Young Hyun Yeo,1 Keon-Hyung Lee,2 Hye Jeong Kim3

1Department of Public Administration, Sunmoon University, Asan, ChungNam, South Korea;

2Askew School of Public Administration and Policy, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA; 3Department of Public Administration, Sunmoon University, Asan, ChungNam, South Korea

Abstract: Just as living organisms have a creation-maintenance-extinction life cycle, organizations also have a life cycle. Private organizations will not survive if they fail to acquire necessary resources through market competition. Public organizations, however, continue to survive because the government has provided financial support in order to enhance public interest. Only a few public organizations in Korea have closed. With the introduction of new public management since the economic crisis in 1997, however, public organizations have had to compete with private organizations. Public hospitals are not free to open or close their business. They are also controlled by the government in terms of their prices, management, budgets, and operations. As they pursue public interest by fulfilling the government’s order such as providing free or lower-priced care to the vulnerable population, they tend to provide a lower quality of care and suffer a financial burden. Employing a case study analysis, this study attempts to understand the external environment that local public hospitals face. The fundamental problem of local public hospitals in Korea is the value conflict between public interest and profitability. Local public hospitals are required to pursue public interest by assignment of a public mission including building a medical safety net for low-income patients and managing nonprofitable medical facilities and emergent health care situations. At the same time, they are required to pursue profitability by achieving high-quality care through competition and the operation of an independent, self-supporting system according to private business logic. Under such paradoxical situations, a political decision may cause an unexpected result.

Keywords: local public hospital closure, publicness, organizational life cycle, South Korea

Introduction

Just as living organisms have a creation-maintenance-extinction life cycle, organizations also have a life cycle. Private organizations will not survive if they fail to acquire necessary resources through market competition. Public organizations, however, continue to survive on government subsidy to promote public interest. After the financial crisis in 1997, many Asian countries including Korea have adopted a more market-oriented economy.1 The public enterprise reform2 and privatization were a reaction to efficiency pressures from the market.3,4 With the new public management movement, a great number of governmental functions have been privatized in the USA. Some researchers call the USA a “hollow state”.5 Since the economic crisis in 1997, the public sector in Korea has followed the US trend and emphasized efficiency and customer-focused, market-oriented management. Such changes have caused a great number of public organizations to shut down.6

The new public management (NPM) has affected public sector reform in many countries including Korea, which has partially adopted NPM and taken various reform initiatives for the enhancement of the quality of service.7 The NPM movement has neglected the legitimacy of public interest but valued organizational profitability, and this neglect may result in the closure of public organizations including public hospitals. In many countries, public hospitals are established and operated by public organizations with a government subsidy in order to promote public interest. Such a subsidy supports organizational sustainability, and the amount of the subsidy received can be used as one of the organizational performance criteria.8

Among all the hospitals in Korea, about 7% are public hospitals. There are 33 regional public hospitals with the closure of Jinju Medical Center in 2013. Local public hospitals have been financed by local governments. They carry out public health policy (set by both central and local governments) and provide medical services to low-income people. In Korea, in February 2013, Governor Hong of Gyeongsangnam-do Province announced that Jinju Medical Center, a local public hospital with a 103-year history, would close because of low efficiency and a financial burden on his local government. With its closure, the value of public hospitals has become a big social issue. Those who support a selective welfare system have argued that a market should substitute inefficient public hospitals. Those who believe in a universal welfare system, on the other hand, have argued that public hospitals should be maintained even if they do not generate a profit because such inefficiency is inevitable and is mainly due to the public value of protecting the socially disadvantaged.9

This research focuses on the creation-maintenance-extinction life cycle of public hospitals in terms of different operation and management systems in each stage of their life cycle. Public hospitals have two different perspectives. One is to provide high-quality public health services including the provision of medical services, disease prevention, and the provision of welfare services; the other is to generate a profit while competing with private hospitals. From a macroscopic perspective, regional public hospitals are established and operated based on governmental law and the public budget. From a profit perspective, however, they are affected by the choice of medical service users as they compete with private hospitals. Furthermore, profitability is one of the important indicators in the performance indices that evaluate the operating condition and the effectiveness of regional public hospitals.

The fundamental problem of local public hospitals in Korea is the value conflict between public interest and profitability. Local public hospitals are required to pursue public interest by assignment of a public mission including building a medical safety net for low-income patients and managing nonprofitable medical facilities and emergent health care situations. At the same time, they are required to pursue profitability by achieving high-quality care through competition and the operation of an independent, self-supporting system according to private business logic. Based on the organizational life cycle model, this research examines the establishment, operation, and the closure of Korean local public hospitals. Further, the researchers investigate the reasons for the closure of Jinju Medical Center.

Background on the Korean health care system

The proportion of public hospitals in the Korean hospital market is only 7% (12% of total hospital beds and 6% of the number of hospitals), which is one of the lowest shares and significantly lower than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average.10 Private hospitals play a public role as they are required to provide medical services to national health insurance (NHI) beneficiaries. Korean private hospitals cannot distribute their profits to stockholders but have to reinvest in their organizations as there is no establishment of for-profit hospitals allowed. With NHI, the shortage of public health infrastructure has been covered by exploiting private hospitals as the government may assign them as an NHI-designated hospital.

Since the implementation of the employer-based health insurance in 1977, the Korean government continuously expanded its insurance coverage and finally implemented the NHI in July 1989. It took only 12 years to fully provide insurance coverage for the people. Korean citizens are required to enroll in the NHI, and their premium rates depend on their income and assets. There are about 1.8 million low-income people covered by medical aid services.

Although Korea implemented an NHI program, the government spent 54.5% of all medical care expenditure, which is lower than the OECD average of 72.3%. The proportion of medical care expenditure in the GDP has rapidly increased from 6.4% of the GDP in 2007 to 7.6% in 2012. This increase was the highest among all OECD countries (OECD average: 2.3%)

Data and method

We performed a case analysis to understand the closure of Jinju Medical Center by employing an organization life cycle approach.11 For the analysis, five data sources were used: 1) local public hospital’s annual budget and closed financial statements; 2) 2013 Statistics for Hospital Management (income statement, balance sheet, number of inpatients and outpatients, profit from medical services, manpower, etc.); 3) The Report on Local Public Hospital’s Operational Assessment (occupancy rate, the ratio between revenue and labor cost, revenue per specialist, etc.); 4) other reports on local public hospitals made by legislators; and 5) statistical information used in the literature.

A great amount of statistical information on local public hospitals was available through Ministry of Health and Welfare’s (MOHW) portal (rhs.mohw.go.kr). Also, the current Park Administration has attempted to open approved government documents to the public. It is available through the government information portal (http://www.open.go.kr) even without requesting to access public information. Such service is one of core tasks that the ‘Government 3.0’ (Government 3.0’ promotes public data to “open, share communicate, and cooperate for” improvement of government services.) has focused on.

Life cycle of public organizations and public hospitals

Organizations are dynamic organisms that perpetually change. Such changes in organizations can be compared to the life of human beings and called the life-cycle hypothesis. There are various patterns in organizational change. Previous research on the life cycle of organizations primarily used private organizations that are determined by market forces such as profit margin, market share, and the amount of sales.12 There is, however, very little research on the lifestyle of public organizations.11,13

Kaufman11 examined the organizational change of executive agencies and presidential committees by classifying them into birth, survival, and death, starting from 1973. There were 175 organizations in 1923; among those, 148 organizations (about 85%) survived and 27 died up to 1973. Peters and Hogwood13 criticized Kaufman’s classification of the permanence and stability of public organizations and created instead four categories: initiation, maintenance, termination, and succession. Succession was then divided into linear, consolidation, partial termination, splitting, nonlinear, and complex.

Birth of an organization

The birth of an organization occurs when there is social activity as an organization, which can be either official or unofficial, and an organization may originate based on legislation. According to Bozeman,14 public organizations do not mean governmental agencies only. All organizations have both public and private characteristics depending on their roles, sources of funding, and level of governmental control. Not only nonprofit but also for-profit organizations, therefore, possess characteristics of public organizations.15

Bozeman defines publicness as “the degree to which the organization is affected by political authority”.16 More specifically, the degree of publicness is based on financial resources, life cycle, organizational structure, and organizational goals. Based on such criteria, at the birth of an organization, if it is financed by government, established by law, and affected by governmental purposes, its degree of publicness would be high.

Growth period of an organization

The growth and development stage of an organization can be divided into two, three, four, and five stages.17,18 Greiner17 argued that as organizations experience a crisis of leadership, autonomy, control, and red-tape, they will mature through the establishment of direction, delegation, coordination, and cooperation. On the contrary, Smith19 employed the chaos theory to explain organizational reform and change.

Ever since the global financial crisis, in order to minimize the financial burden, governments have merged or consolidated various public organizations. The effectiveness of such efforts, however, has not been verified. As Kaufman11 insisted, public organizations prolong their continuity and immortality by changing their organizational goals, consolidating with other organizations, and adopting new management approaches. Most public organizations politically acquire their budgets instead of obtaining funds by selling products in the market.20 Despite changes in the environment and the resulting pressures, public organizations have pursued continuity by seeking new roles as well as changing their names and organizational goals. As Chun and Rainey21 mentioned, it is difficult to find objective evaluation criteria on how well public organizations have met the demands of various customers. At this time, government entities recognize the need for evaluation and control. While for-profit organizations utilize more objective evaluation criteria such as profit margin, market share, and sales amount, the performance evaluation criteria of public organizations are created through political processes. Various and disconnected political factors make it difficult for public organizations to develop objective performance evaluation criteria. Since most public organizations acquire their budgets through political processes, they are controlled by a great number of external forces including Congress and other political organizations. Thus, the strong permeability of external pressures causes public organizations to imitate the new management styles of other organizations.

The decline and extinction of an organization

Organizational survival is closely related to the categories of succession, integration, division, and extinction. Thus, when examining an organizational survival period, it is important to consider such categories. Public organizations are more stable compared to private ones. Although governmental functions may be enhanced or reduced, the initiation and succession of public organizations remains relatively high. Yet, public organizations may be in decline or extinction because of political and legal changes, and lack of resources.22 Especially since the 1980s, one of the main characteristics of NPM, as the leading administration reform scheme, has been the reduction of the public sector. A good example of this is when public functions are transferred to the private sector that eventually leads to the closure of public organizations. A reduction in public financial support has threatened public organizations. Further, since budgetary processes are political, public organizations are affected not only by the legislative branch but also by interest groups, the media, and the public.

The role and status of local public hospitals in Korea

Role of local public hospitals

The publicness of health services or the publicness of public hospitals depends on the role of government in public health. The publicness of health services means that the beneficiaries of such services are universal. Contrary to individual services, it means that health services are provided to the general public. Public health services promote health and disease prevention for the general public, but private health services are mainly for individual clinical care.23 The publicness of health services may mean universal health services, benefits to the public, or health services.

Differences between public and private health care provision have been of interest to researchers for many years. Early studies in this area focus on differences in performance between profit, nonprofit, and public hospitals.24,25 They found that nonprofit providers did better on cost than the for-profits in the majority of studies, and a majority of previous studies reported that nonprofits were superior to for-profits on quality and the amount of charity care provided. Helmig and Lapsley26 examined the efficiency of public, welfare (nonprofit), and private (for-profit) hospitals in Germany. They found that hospitals in the public and welfare sectors were relatively more efficient than private hospitals. They suggested that public and welfare hospitals appear to use fewer resources than private hospitals. According to the World Health Organization definition,27 public health services include health situation analysis, health surveillance, health promotion, prevention services, infectious disease control, environmental protection and sanitation, disaster preparedness and response, and occupational health.

Other aspects of economic authority include the extent to which the organization is able to raise capital, set borrowing limits, and retain financial surpluses. Renn et al28 insisted that hospitals owned by for-profit groups charged more and were more profitable than all other types except independent for-profit ones. Organizations, even public hospitals, with high economic authority are subject to tight government financial control. In Korea, a recent policy change has resulted in a shift of emphasis from output to outcome, stressing the efficiency at public hospitals. The outcome described encompasses public service outcomes and financial balance such as inpatient number and medical revenue. This condition makes the goal of public hospitals more ambiguous.

The publicness of health services in Korea, however, means not only health care services provided by public hospitals, but also implementing actions that maximize the benefit of the public or delegating public functions from the government to private hospitals as well. The Korean government may designate private hospitals as public health service organizations and the Korean NHI system also utilizes private hospitals as designated health service facilities. Furthermore, the government designates private hospitals in medically underserved areas or in places where public specialty health service centers are needed.

As the Korean government may assign private hospitals as NHI-designated hospitals and force them to provide public health services, the need for the expansion of public hospitals had not been an issue. Korea has a government-led health service system and does not allow the establishment of for-profit hospitals (except for foreign investment in free-trade zones).

There are 33 local public hospitals in Korea; eleven of these have a history over 100 years and the average age of all local public hospitals is about 76 years. In 1925, the Japanese colonial government transferred the management rights of these local hospitals to local governments and this system has continued to the present. In addition, after the Local Public Enterprise Act of 1980, a local government could establish a new local public hospital.

With the enactment of the Establishment and Operation of Local Public Hospital Act of 2005, the Korean central government codified that local governments are responsible for the establishment, management, and operation of local public hospitals. The primary functions of local public hospitals are providing medical care to the local residents, controlling infectious diseases, operating nonprofitable services such as hospice and rehabilitative services, and serving as safety-net hospitals for vulnerable populations. As of October 2013, 33 local public hospitals have been in operation, and 28 of these are general hospitals.

Although over 90% of centers offer internal medicine, general surgery, and orthopedic surgery, less than 50% of local public hospitals offer thoracic surgery, psychiatry, and rehabilitation medicine because of a physician shortage. Local public hospitals have, on average, 7.8 doctors per 100 beds, which is lower than that of private hospitals (11.8 doctors), and the physician turnover rate is 23.7%. As of 2011, there are 46.1 nurses per 100 beds in local public hospitals, whereas there are 51.8 nurses per 100 beds in private hospitals. The number of inpatients per 100 beds at public hospitals was 29,384 in 2009, 30,240 in 2010, and 32,251 in 2011, whereas the number of inpatients at private hospitals was 30,952 in 2009, 32,266 in 2010, and 32,193 in 2011. Public hospitals had a lower number of inpatients than private hospitals. The average occupancy rates of public hospitals were 84.4% in 2011 and 83% in 2012.

In general, the number of outpatient visits in local public hospitals was higher than in private hospitals. Compared to the similar size of private hospitals, local public hospitals provide medical services at a lower cost, serve more low-income people, provide fewer noncoverage services, and have lower insurance fees.29 Because of these reasons, all 33 local public hospitals have suffered financial problems.

Government subsidy of local public hospitals for publicness

South Korea is a strong centralized state. Although it has an autonomous local government system, a large number of local governments have relied heavily on funding from the central government because of low financial independence. In 2015, the local governments had an average budget of US$14.7 million and their financial independence ratio was 45.1%. With a subsidy from the central government, local governments have been able to operate social welfare services. As local governments increased their social welfare service budgets, they received more subsidies from the central government, but they have not been able to increase their revenues because of the economic recession.

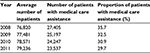

As shown in Table 1, compared to private hospitals, local public hospitals had lesser inpatient revenue from medical services. Local public hospitals generated $5.71 million and $6.44 million in 2010 and in 2012, respectively, whereas private hospitals generated $7.59 million and $8.01 million for the same years. The possible reasons for the reduced inpatient revenue in local public hospitals are lower reimbursement rates, the provision of charity care to low-income people, and low-revenue generating services such as obstetrics and gynecology and pediatric services in medically underserved areas.

| Table 1 Inpatient revenue per 100 beds Note: Data from National Medical Center.29 |

While the central government had provided very little in the way of subsidy for local public hospitals in the past, it began to support the infrastructure of local public hospitals by the end of 2000. Even with the current financial support from central and local governments, local public hospitals cannot provide their services effectively. Unless there is a sustainable support from the government, the local hospitals continue to suffer financial loss. As the conservative political groups have increased their political pressure to cut down the size of public organizations, local public hospitals have encountered such pressure.

As shown in Table 2, from 2008 to 2012 – for 5 years – the central and local governments provided a total of $713 million support ($42.37 million per local public hospital per year). Among those, the central government provided $212.7 million support for facilities and equipment; local governments provided $500.3 million support for operating expenses.

| Table 2 Details of the subsidy to local public hospitals, 2008–2012 (US$ million) Note: Data from MOHW.30 Abbreviation: MOHW, Ministry of Health and Welfare. |

The central government provided $34.7 million support in 2011, $33.1 million in 2012, and $44.1 million in 2013 for facility expansion and equipment acquisition.30,31 Local governments subsidized any loss of operating expenses. Local public hospitals with 300 or more beds have received larger subsidies because they offer more public functions by providing psychiatric services, rehabilitation services, and a free clinic. As the local public hospitals incurred larger financial losses, local governments received a subsidy of $56.9 million annually from 2008 to 2012. Local governments with low financial independence felt financial pressure and suffered from an increasing number of delayed disbursements of wages.

Private hospitals only have 8.1% of inpatients in the medical aid program but, as shown in Table 3, local public hospitals have had a much higher proportion of inpatients in the medical aid program (<200 beds: 29.4%; 200–299 beds: 28%; >300 beds: 32.8%). As local public hospitals function as safety-net hospitals, they tend to offer nonacute care such as psychiatric care, rehabilitation services, and other nonlucrative services.32

| Table 3 Proportion of patients with medical care assistance in local public hospitals Note: Data from Kim.33 |

Public control system during the life cycle of local public hospitals

The birth stage (control of establishment)

Local governments have the right to establish local public hospitals, and they must provide the establishment expense or support for the operating expenses. Before a hospital is established, local governments must fully evaluate the impact on existing local public hospitals with respect to health promotion, community health services, and the feasibility of the project, such as 1) when merging two or more local public hospitals or opening a branch; 2) when closing a local public hospital; 3) when expanding, moving, or selling a local public hospital; and 4) when making important changes that may affect the operation of a local public hospital. To establish a local public hospital, after the feasibility review, the local assembly may enact an ordinance and register the new hospital. It is difficult to manage and operate a local public hospital without interference from the government.33

From a resource-publicness perspective, local public hospitals in Korea receive financial support from local governments. Thus, their organizational existence is heavily dependent upon the government and not the market. Every aspect (eg, personnel management, finance, contracts, supply chain management, etc) of the organizational operation is affected by the government as they carry out government-imposed goals and objectives. From the birth of the organization, local public hospitals show strong public characteristics with the receipt of public financing, the pursuit of government-imposed goals and objectives, and a heavy reliance on the government. Enacted by governments and financed by public funds, such organizations (ie, local public hospitals) tend to carry out public activities and grow with public funds.

The growth stage (operational control)

Local governments may establish local public hospitals but do not operate them. The primary reasons for local governments to establish local public hospitals are to serve as a safety-net hospital and to provide nonlucrative services such as emergency care, infectious disease control, hospice care, and rehabilitation services. Moreover, the central government designates “regional base public hospitals” to carry out specific public missions. All local public hospitals are regional base hospitals that provide free care to patients with chronic conditions, vulnerable populations, and foreign laborers based on the government quota, for which the central government provides a subsidy.

As organizational publicness gets stronger, the government’s external control of public organization accountability gets stronger.34 When the publicness of an organization is high, the external control becomes vertical and hierarchical. As the organizational characteristics show higher publicness, an organization confronts a higher external demand for various organizational aspects such as appropriations, man-years, concrete cases, complaints, and appointment of leaders.35

The local public hospitals are controlled by a double-control system done by both the central and local governments. The central government deals with policy, while the local governments deal with the establishment and the operation. The central government controls the following aspects: 1) organizational policy and goals; 2) performance evaluation; and 3) service quality, price, and accounting. Local governments, on the other hand, appoint the CEO, approve the closing account, and come up with the establishment expense or support for the operating expenses. Local governments control the following aspects: 1) establishment and closure; 2) senior management and board of directors; 3) budget; and 4) organizational composition and staffing.

The central government shapes the policy that deals with the evaluation and diagnosis of the operation, and guidance and oversight of accounting procedures.36 In order to achieve efficient operation of local public hospitals, the central government announces the results of operational evaluations or asks for a business improvement plan from the governor or the CEO of a local public hospital. To carry out public health service activities, the central government may establish a new local public hospital, expand facilities or equipment, acquire highly qualified medical personnel, and support operating expenses. The strongest control mechanism that the central government employs is the annual performance evaluation of local public hospitals. During the evaluation, the central government reviews various aspects of local public hospitals including financial conditions, proportion of public health service activities, contributions to health promotion of residents, efficiency, and customer satisfaction.

Operational evaluation by the central government (usual performance evaluation)

Based on the Establishment and Operation of Local Public Hospital Act, the central government performs annual performance evaluations on local public hospitals, through which the MOHW understands their functions and performance and reflects them when revising policy.

A government-commissioned performance evaluation team first reviews operational documents and financial statements of local public hospitals before visiting the site. The team makes the final report based on its review on operational documents, financial statements, and the site visit, which is notified to each local public hospital that may appeal for any discrepancies. The MOHW conveys the final result of the evaluation to local public hospitals, and the CEO should notify the result to all employees, if necessary, in order to come up with an improvement plan.

The main performance criteria are profitability and publicness, but several evaluation criteria are used during the annual evaluation, such as, responsible management, financial independence, hospital management, social contribution, and medical care. The evaluation methods used are document inspection, onsite visits, and surveys (telephone and internet). Based on the evaluation results, local governments provide incentive payments to the CEOs and employees and also provide support for overcoming weaknesses in the medical center.

As shown in Table 4, the medical costs of local public hospitals were lower – about 54%–78% – than those of private hospitals.37 Three local public hospitals contracted out their management to university hospitals during the 1990s in order to lower financial losses and improve quality of care. With this, they experienced a smaller financial loss mainly due to an increase in the patient cost-sharing portion of medical costs: 1) outpatient revenue ÷ outpatient visits; and 2) inpatient revenue ÷ inpatient days. All other local public hospitals, however, had lowered the average of their patient revenue.38

| Table 4 Comparison of the average patient revenue between local public hospitals and private hospitals Notes: Data from 2009–2012 Local Public Hospitals Financial Report.47 Currency in US$. |

There are four domains of evaluation: high-quality medical care, rational management, health services for public interest and benefit, and social responsibility. High-quality medical care can be summarized as high patient satisfaction, secondary care for the acute phase, effective care with low cost, and better care than private hospitals. Rational management refers to organizational operation and focuses on management by objectives, dynamic organizational management, human resource capacity building, transparent management, effective leadership, and financial performance. Health services for public interest and benefit means serving as a safety-net hospital, providing inclusive services, responding to unmet needs such as long-term care and rehabilitation services, and performing according to central and local government policies. Social responsibility deals with the participative decision-making process, sharing responsibility among different groups, employment stability, and community services.31

Based on the evaluation results, the central government may reprimand the CEO of a local public hospital, determine an incentive payment amount, reduce the organizational size, and change the government subsidy amount. Thus, local public hospitals are under great pressure from the annual performance evaluation.

Operational diagnosis (diagnostic evaluation when problems exist)

In addition to the annual operational evaluation, there is an operational diagnosis, during which the central government performs an in-depth analysis of those problems and issues that arose during the operational evaluation period and proactively responds to them. All local public hospitals must annually receive an operational evaluation. However, an operational diagnosis is only for those local public hospitals with serious managerial problems and issues. The minister of MOHW performs an operational diagnosis in three situations: 1) when the local public hospital has been incurring a financial loss for 3 years or more consecutively; 2) when there is a significant reduction in revenues compared to the previous year, without any particular reason; and 3) when organizational restructuring is needed because of a reduction in operational scope, inability to carry out public health functions, or to close the business. Based on the results of the operational diagnosis, the MOHW requests the governor or the CEO to restructure the organization or to develop an improved plan for operation. Such requests may include a dismissal of senior management and/or restructuring of the organization. The governor or the CEO must follow the request unless she/he has a legitimate reason.

The death stage

Exit system

During the last 3 years, 6,153 private clinics and hospitals were established, and 4,495 were closed; the proportion of the newly established to those that closed is 73%. A part of the reason for a large number of establishments and closures of private clinics and hospitals is higher market competition. In South Korea, patients tend to prefer large general hospitals, specialized hospitals, and hospitals located in a metropolis, with large general hospitals being the most preferred. Therefore, rather than primary care or secondary local hospitals, patients are concentrated in large general hospitals and tertiary medical institutions. As a result, there are eleven local public hospitals that have a history of over 100 years, and the average organizational age is 76 years, but Jinju Medical Center was the first and only closure among all local public hospitals.

It is difficult to obtain information or criteria that objectively evaluate how much the public organizations meet the needs of various political environments.21 Private organizations have objective measures such as profitability, market share, and sales volume. The outcome of public organizations, on the other hand, is susceptible to political judgment and the absence of performance criteria.39 Therefore, it is hard to determine which organizations should be eliminated. Kaufman11 conducted an empirical study investigating the types of government organization change including establishment, succession, and repeal, and found that the function of government becomes either enhanced or weakened, but did not suddenly appear or disappear, because government organizations were relatively stable. When it comes to local public hospitals in South Korea, they are under the strong control of the central government by means of performance evaluations and diagnoses.

There is an explicit exit system for local public hospitals under Korean law: 1) The governor shall consult with the Minister of Health and Welfare in advance to decide on closure or dismissal of a local public hospital. Details of the consultation time and process are determined by Presidential Decree; 2) The property of a local public hospital is treated as prescribed by its bylaws. However, the remaining property which belongs to government subsidies can be either returned to the national treasury or used for public health service activities; 3) If the governor decides to close or dismiss a local public hospital, she/he shall inform the CEO of the following and monitor the implementation:

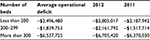

A study by the MOHW and the National Medical Center29 estimated that a total financial loss of all 34 local public hospitals in 2012 was $112,372,881 and about 61% of such deficit was mainly due to carrying out goodwill publicness. As shown in Table 5, local public hospitals have suffered from operational deficits, and if they have deficits for 3 years consecutively, they are subject to an operational diagnosis, on the results of which might lead to closed.

| Table 5 Average operational deficits of local public hospitals in 2011 and 2012 Note: Data from MOHW.31 Abbreviation: MOHW, Ministry of Health and Welfare. |

The only case of closure is Jinju Medical Center, which was closed in 2013. In other words, other local public hospitals were preserved despite consistent deficit, and the closure of Jinju Medical Center was an unusual event which caused political conflict between the ruling and opposition parties. When a person from the ruling party was appointed as the CEO of Jinju Medical Center, he decided to close the hospital based on deficit and inefficiency, but the opposition party, civic groups, and labor unions opposed this action because they said that such a decision ignores the public role of the Jinju Medical Center.

Thus, without government funding, local public hospitals cannot survive. The constant deficits faced by local public hospitals are largely due to outdated facilities, lack of medical staff, the perception that they are only for low-income people, and failure to properly adapt to a rapidly changing health care environment.32,40 Such deficits are an inevitable byproduct of providing public health services. Some argue that such deficits should be subsidized as local public hospitals offer essential medical care and public health services.

The case of local public hospitals’ death

The abovementioned system is no more than a general guideline and does not provide clear standards or specific conditions for hospital closures. Jinju Medical Center is one of the oldest local public hospitals with a 103-year tradition. On February 26, 2013, Gyeongsangnam-do officially declared the closure of Jinju Medical Center due to a cumulative deficit, with the actual closure on May 29, 2013. Except for the hospitals that were absorbed into other local public hospitals or those that changed their functions, the closure of Jinju Medical Center is recorded as the first local public hospital closure. This caused social and political debates about the role of public health in Korea.

In addition to the cumulative deficit of local medical centers, there has been criticism that these hospitals do not perform sufficient public health functions and roles. The proportion of medical aid patients per year at local public hospitals has been decreasing from 31.3% in 2007 to 22.1% in 2013, and the proportion of outpatients is also on the decline from 20.5% to 14.8% in 2013.29 Even though the deficit was the main reason given for the closure of Jinju Medical Center, another debate about the relationship between local public hospitals and their finances has surfaced.

Opposition parties, labor unions, and nongovernmental organizations have argued that local medical center deficits are “good deficits”, “public deficits”, or “healthy deficits”. A good deficit can be defined as ‘inevitable” losses from the provision of public activities, the maintenance of social safety nets, implementation of central and local government policies, and public activity for communities. The factors that cause a good deficit are medical expense support for low-income patients, a high proportion of medical aid patients, and other public medical activities.41 Also, local medical centers established in vulnerable areas are influenced by the number of patients (volume), as well as inpatient and outpatient approaches.

Local public hospitals mainly target vulnerable groups. Almost all such centers show a deficit, which means their businesses cannot be justified through market logic, but they can be justified for their public roles. Before its closure in 2013, Jinju Medical Center reported a deficit of $4,152,542 in 2010, $5,338,983 in 2011, and $5,847,458 in 2012.42–44 When it was closed in 2013, none of the local public hospitals across the country (34 hospitals) generated a net profit.

Local public hospitals aim to provide essential medical services that private hospitals hesitate to provide. The proportion of inpatient medical aid patients is 17.3%, which is higher than the average (7.1%). Local public hospitals located in medically vulnerable areas run three acute care clinics on average – such as pediatrics, gynecology, etc. – and these are the only acute care clinics in the area. Furthermore, local public hospitals operate essential health services that are not profitable. For instance, they have 2.1 times more isolated beds and 2.7 times more hospice beds compared to the equivalent private hospitals.

Among all 34 local public hospitals, 64.7% (n=22) had an average debt of over $8.5 million. In particular, the average debt of general hospitals with more than 300 beds was $22.1 million, which shows little difference from that of Jinju Medical Center with 320 beds. Despite this, only Jinju Medical Center was closed.

The main reason for the closure of Jinju Medical Center was the political belief of the governor who took charge of the hospital’s operation and management. Hong Jun-pyo, Governor of Gyeongsangnam-do, declared the closure of Jinju Medical Center because of debt, deficit, and belligerent labor unions, and also claimed that the local government was going to use the subsidy that had gone to Jinju Medical Center to support other public health assistance and social welfare programs. The former medical center would be used as the second local office of Gyeongsangnam-do. Likewise, when a conservative party politician is elected as a governor, she/he tends to go through structural reforms focusing on privatization and the reduction of the size of the public sector, and the closure of Jinju Medical Center was one of these policy decisions.

Conclusion and discussion

South Korea is a strong centralized state. Although it has an autonomous local government system, a large number of local governments heavily rely on subsidy from the central government because of low financial independence. The creation, operation, and extinction of local public hospitals are by law controlled by the government. Most of the local public hospitals have suffered financial loss. However, why was only Jinju Medical Center closed because of financial loss? Local public hospitals are neither the public nor market sectors. They have features of both public and private organizational characteristics and goals.25 Governor Hong was a newly elected politician who is conservative, promarket, and anti-universal welfare. He made a political decision to close the organization with deficit.

Local public hospitals are required to pursue two opposite objectives. They face paradoxical conditions where they are required to provide public health as well as profitability. The development of local public hospitals is behind that of private hospitals because the central government has not supported the budgets of local public hospitals, causing a time lag in modernization and a lack of operating expenses. However, the central government only provides budgetary support for building facility infrastructures. Also, local governments have been urged to secure profitability through reforms in local public hospitals based on their financial capability. The closure of a hospital is dependent on the personal political belief of the governor while neither the central nor the local government has experience in systemic management, health care specialization, and clear criteria for the levels of care.45

With the financial crisis in 1997, the International Monetary Fund recommended the implementation of neoliberal economic policies such as the free market system, deregulation, and privatization. Up until then, a majority of Koreans believed that the legitimacy of the existence of public organizations is to enhance publicness. Although President Kim Dae-jung was more liberal, his administration enacted the Privatization Act. The government’s plan designated a total of eleven public enterprises for privatization including the KT, POSCO, Hanjung, and KT&G.46 A similar pressure was also promoted to local public hospitals. Governor Hong decided to close Jinju Medical Center because of financial loss and a burden on his provincial government.

With this decision, the Korean society is paying a great amount of social costs of conflict between the conservatives and the progressives. In the future, it is expected that the pressure on local public hospitals will increase due to demands for financial improvement. With the criticism and the lawsuit by the opposition party, civic groups, and labor unions, there may be few politicians who will take such adventurous routes. When politicians make a decision, they should do so based on what is good for the public.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2013S1A2A1A01066810).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Jho WS, Yoo TY. Ideas, networks, and policy change: explaining strategic privatization in Korea. Korea Observer. 2014;45(2):179. | ||

Lim WH. Public Enterprise Reform and Privatization in Korea: Lessons for Developing Countries. Seoul, Korea: Korea Development Institute; 2003. | ||

Gilardi F. The institutional foundations of regulatory capitalism: the diffusion of independent regulatory agencies in Western Europe. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2005;598(1):84–101. | ||

Pempel T. Japan’s search for the ‘sweet spot’: international cooperation and regional security in northeast Asia. Orbis. 2011;55(2):255–273. | ||

Milward HB, Provan KG. Governing the hollow state. J Publ Admin Res Theory. 2000;10(2):359–380. | ||

Yang J. Public sector reforms. In: Harvie C, Lee H-H, Oh J, editors. The Korean Economy: Post-Crisis Policies, Issues and Prospects. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar; 2004:120–142. | ||

Kim PS, Moon MJ. Current public sector reform in Korea: new public management in practice. J Comp Asian Dev, 2002;1(1):49–70. | ||

Leone AJ, Rock S. Empirical tests of budget ratcheting and its effect on managers’ discretionary accrual choices. J Account Econ. 2002;33(1):43–67. | ||

Shin Y. Assessing the performance of local public medical center: a harmony between publicness and profitability. J Policy Eval Manag. 2005;15(1):177–211. | ||

OECD Health Database. 2010. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT. Accessed March 20, 2016. | ||

Kaufman H. Are Government Organization Immortal? Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 1976. | ||

Min J. A study on the organizational change in Korean central government agency. Korean Soc Publ Admin. 2006;17(2):1–23. | ||

Peters BG, Hogwood BW. The death of immortality: births, deaths and metamorphoses in the US federal bureaucracy 1933-1982. Am Rev Publ Admin. 1988;18(2):119–133. | ||

Bozeman B. Dimensions of publicness: An approach to public organization theory. In: Bozeman B, Straussman J, editors. New Directions in Public Administration. Belmont, CA: Crooks/Cole; 1984:46–62. | ||

Nutt PC, Backoff RW. Organizational publicness and its implications for strategic management. J Publ Admin Res Theory. 1993;3(2):209–231. | ||

Bozeman B. All Organizations are Public: Bridging Public and Private Organizational Theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc Pub; 1987:72. | ||

Greiner LE. Evolution and revolution as organization grow. Harvard Business Review. 1998;76(3):55–68. | ||

Cameron K, Whetten DA. Perception of organizational life cycle. Admin Sci Q. 1981;26:525–544. | ||

Smith A. Complexity theory and change management in sport organizations. Emergence-Mahwah-Lawrence Erlbaum. 2004;6(1/2):70. | ||

Dahl RA, Lindblom CE. Politics, Economics and Welfare. New York, NY: Harper; 1953;341–344. | ||

Chun YH, Rainey HG. Goal ambiguity and organizational performance in US federal agencies. J Publ Admin Res Theory. 2005;15(4):529–557. | ||

Cameron K, Zammuto R. Matching managerial strategies to conditions of decline. Hum Resource Manage. 1983;22(4):359–375. | ||

Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. The New Public Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2014. | ||

Cromwell J, Puskin D. Hospital productivity and intensity trends: 1980–87. Inquiry. 1989;26:366–380. | ||

Anderson S. Organization studies and the analysis of health systems. Soc Sc Med. 2012;74(3):313–322. | ||

Helmig B, Lapsley I. On the efficiency of public, welfare and private hospitals in Germany over time: a sectoral data envelopment analysis study. Health Serv Manag Res. 2001;14:263–274. | ||

World Health Organization. La salud pública en las Américas: nuevos conceptos, análisis del desempeño y bases para la acción. Publicación científica y técnica. Organización Panamericana de la Salud: No. 589. Washington, DC, 2002. | ||

Renn SC, Schramm CJ, Watt JM, Derzon RA. The effects of ownership and system affiliation on the economic performance of hospitals. Inquiry. 1985;22:219–236. | ||

NMD (National Medical Center). 2013 Year’s Regional Base Hospital Performance Evaluation. Seoul; 2013. | ||

MOHW (Ministry of Health and Welfare). Strengthening Public Health by Promoting Local Public Hospitals. Korea; 2013. | ||

MOHW (Ministry of Health and Welfare). Year’s Annual Report of Regional Public Hospital in Korea. Korea; 2013. | ||

Lee DY. A study on the optimal bed size based on the financial performance of local public hospitals, 2010–2012. Seoul, 2013. | ||

Kim MH. 2013 Year’s Special Committee Report of Local Public Hospital. Seoul; 2013. | ||

Romzek BS. Dynamics of public sector accountability in an era of reform. Int Rev Admin Sci. 2000;66(1):21–44. | ||

Antonsen M, Jørgensen TB. The ‘publicness’ of public organizations. Publ Admin. 1997;75(2):337–357. | ||

MOHW (Ministry of Health and Welfare). Implementation Rule of the Establishment and the Operation of the Local Public Hospitals. Korea 2015. | ||

Korean National Medical Center. The Performance Evaluation of the Local Public Hospitals in 2013. Seoul, Korea 2013. | ||

Kim MH. The Special Committee’s Report of Local Public Hospital. Seoul, Korea 2013. | ||

Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 1991. | ||

Lee JW, Kim YJ, Kim YH, Kim KH. A study on decisive factors impacting business profits of regional medical centers. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2014;12(7):315–325. | ||

Jho W, Yoo T. Ideas, networks, and policy change: explaining strategic privatization in Korea. Korea Observer. 2014;45(2):179–210. | ||

KIHASA (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs). Current status and future direction of public medical system, Focus on regional public hospital and national university hospital. Seoul. 2014. | ||

Park YB. Privatization and employment in the Republic of Korea. In: van der Hoeven R, Szirackzi G, editors. Lessons from Privatization: Labour Issues in Developing and Transitional Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office; 1997:21. | ||

The Korean Association of Regional Public Hospital. 2010 year’s Annual Report. Seoul; 2012. Available from: http://www.medios.or.kr. Accessed March 15, 2016. | ||

The Korean Association of Regional Public Hospital. 2011 year’s Annual Report. Seoul; 2013. Available from: http://www.medios.or.kr. Accessed March 15, 2016. | ||

The Korean Association of Regional Public Hospital. 2012 year’s Annual Report. Seoul; 2014. Available from: http://www.medios.or.kr. Accessed March 15, 2016. | ||

The Korean Association of Regional Public Hospital 2009–2012. Local Public Hospitals Financial Report. Available from: http://www.medios.or.kr. Accessed March 15, 2016. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.