Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 14

Choosing and Using the Progesterone Vaginal Ring: Women’s Lived Experiences in Three African Cities

Authors Undie CC, RamaRao S , Mbow FB

Received 9 June 2020

Accepted for publication 8 August 2020

Published 28 September 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 1761—1770

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S265503

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Chi-Chi Undie,1 Saumya RamaRao,2 Fatou Bintou Mbow3

1Reproductive Health Program, Population Council, Nairobi, Kenya; 2Reproductive Health Program, Population Council, New York, NY, USA; 3Reproductive Health Program, Population Council, Dakar, Senegal

Correspondence: Chi-Chi Undie Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study explored experiences of selecting and utilizing a newly introduced contraceptive – the progesterone vaginal ring (PVR) – among women seeking a contraceptive method in 3 African capital cities (Abuja, Nairobi, and Senegal). The study explored women’s perceptions of, and lived experiences with, using the new product to better understand their reception of a new contraceptive. This understanding will help inform the design of programs to support women in their adoption and continued use of the PVR and other new contraceptives.

Patients and Methods: This longitudinal, qualitative study drew on an interpretive phenomenological approach, involving multiple in-depth interviews (IDIs) with 9 study participants over a 6-month period. Participants involved in the study were postpartum women seeking contraceptive services at participating clinics. A total of 25 IDIs were conducted, and a detailed “within-case” and “cross-case” analysis of participants’ accounts was carried out to identify similar and dissimilar themes along descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual lines.

Results: Four overarching themes emerged from the analysis. These themes circulated around the unconventionality of the PVR, which heightened its desirability among participants; the sense of comfort that women gained from opting to use the PVR over other FP methods; narratives of consideration that centered on women’s partners, and that were important for ensuring the sustainability of women’s PVR use; and the conundrums that women grappled with as they prepared to disengage from the PVR after two cycles of use.

Conclusion: The PVR is an acceptable contraceptive method to postpartum women in urban African settings. However, prior to its introduction into new country contexts, formative data on women’s perceptions of, and reactions to, the product need to inform country preparation processes. Such information would be useful for tailoring counseling around this contraceptive, as well as for product marketing and robust uptake of the method.

Keywords: contraceptive rings, postpartum women, women’s experiences, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal

Introduction

Women gain control over their reproductive lives when they are able to have the children they want at the time they want. Contraceptives significantly reduce women’s risk of unintended or unwanted pregnancies and can promote women’s ability to achieve their reproductive desires. Women differ from each other in their need for contraceptive protection based upon their preferences, where they are in their reproductive lives, their family context, and access to family planning services among many other factors.

Women who have just delivered are particularly in need of contraceptive protection as they focus on the newborn and its care. Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 27 countries confirm that nearly universally (94%), postpartum women do not wish to be pregnant within two years.1 Despite a desire to not conceive, a substantial proportion of postpartum women do not use a contraceptive across different social, cultural and health program settings. For example, analysis of DHS data from 21 low- and middle-income countries reported that 61% of postpartum women who do not desire a pregnancy are not using any modern method of contraception, including the lactational amenorrhea method.2

Postpartum women may not use contraceptives for many reasons. Commonly documented reasons for not using a contraceptive range from perception of low pregnancy risk due to breastfeeding, postpartum amenorrhea, waiting for menses to signal return of fertility, and method-related concerns, to not receiving information or relevant services at health facilities.3,4 However, breastfeeding women who wish to prevent pregnancy need a supplemental method after 6 months postpartum, when the failure rate of lactational amenorrhea increases. Nevertheless, even women who might be breastfeeding with the intention of postponing a pregnancy, are less likely to be nursing as much when the baby turns 6 months, and any protection from breastfeeding will decrease to levels lower than that offered by other contraceptives.5

The Progesterone Vaginal Ring (PVR) is an innovative contraceptive that the Population Council and partners designed exclusively for breastfeeding women in the first year postpartum. The PVR is a three-month contraceptive that a woman in the first year postpartum can use as long as she breastfeeds up to four times a day. She can use four rings in succession for a year of protection. The PVR contains natural progesterone similar to what the body produces and is safe for women and their babies,6 making it more acceptable to breastfeeding women. Clinical trials have demonstrated its effectiveness to be similar to that of the IUD.7 A user can insert and remove the ring on her own, thereby reducing the need for additional visits to family planning service centers, time spent, and cost incurred.

This method is well suited for settings where breastfeeding is common. In many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, breastfeeding is universal and women breastfeed on average for 20 months.8 Although breastfeeding is common, the duration of exclusive breastfeeding is much less—often less than 3 months. As a result of less intensive breastfeeding, women can conceive while they mistakenly assume that they are protected from pregnancy because they are breastfeeding. The PVR augments the contraceptive protection that women get from breastfeeding. In other words, women do not need to nurse as intensively, as would be the case as the baby begins to wean, and they will be protected from a pregnancy by the PVR.9

The Population Council conducted an acceptability study of the PVR in the capital cities of Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and the results of the quantitative data analysis have been published.10,11 In the quantitative study, a total of 247 women were screened across all country sites. Of these, 76% (n=189) met the eligibility criteria and provided informed consent to participate in the study. Most of those that met the eligibility criteria (174 out of 189) participated in the quantitative arm. Of these, 110 (63%) used one ring, and 94 (54%) completed participation in the quantitative study by using two rings over a six‐month period.

A total of 28 women in this larger study discontinued PVR use.11 They did so early on (within the first month of use) and for various reasons, including discomfort (9), inadvertent expulsion of the ring (9), slippage sensations (5), wanting a different method (2), and spousal objection to the use of the ring (3). This larger, quantitative study also involved the collection of data from the first 58–60 women in each country who visited the study sites and chose a contraceptive other than the PVR (n=178). Their reasons for not choosing the PVR had to do with perceived comfort, primarily, whether this was associated with perceptions about vaginal insertion (7%), discomfort during sex (35%), or discomfort while toileting (33%). Additionally, a few women reported feeling uneasy about trying a new product (3%), while others preferred to use a longer-acting method (4%).

In the current paper, we explore women’s experiences of choosing and using the newly-introduced PVR through in-depth interviews. The significance of the paper lies in the fact that it provides nuanced information about how women perceive and react to a new product – information that was not adequately captured in our quantitative account due to the limitations of survey methodology. We envisage that our analysis will provide a deeper understanding of how and why women receive a new contraceptive as they are introduced in their settings. Furthermore, it will inform the design of programs to support women in their adoption and continued use of the PVR.

Nonetheless, we draw our conclusions from this qualitative study carefully. The findings and conclusions alike are not driven by a concern for representativeness, as this term is understood in quantitative parlance. Rather, they are driven by conceptual questions, with the goal of “produc[ing] data that are conceptually, not statistically, representative of people in a specific context.”12

Patients and Methods

Study Design

The study was longitudinal and qualitative in nature. It used an interpretive phenomenological approach (IPA), with multiple in-depth interviews conducted with each participant over a 6-month period. Noted as being “especially useful when one is concerned with complexity, process or novelty,”13 this approach aims for a detailed exploration of study participants’ meaning- and sense-making with regard to their personal and social worlds. This paper explores the participants’ personal and social worlds, and how these intersect with using a new contraceptive. Congruent with IPA, no more than 10 participants were included in this study,14 enabling detailed “within-case” analysis of individual accounts and “cross-case” analysis of all participant accounts to identify similar and dissimilar patterns.15

Study Sample

In each country, postpartum, breastfeeding women who were seeking contraceptive services at participating clinics, were presented with the range of methods available. Those who selected the PVR were informed that the method was only available via study participation, and that they could receive it if they met the eligibility criteria. Those who opted for the PVR were found to be eligible for its use after passing screening, and provided informed consent, were fitted by a trained nurse with the PVR.

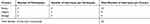

In each country, a total of 2 to 5 PVR users who enrolled in the study were selected for participation in the in-depth interviews, based on their willingness to participate in a smaller, qualitative study, and their being among the first women to express such willingness in the course of the qualitative study. In Kenya, where 5 women were originally recruited for participation, 1 was terminated from the study before any interviews were conducted (her husband was uncomfortable with the fact that he could feel the PVR during sexual intercourse, and this participant, therefore, opted to switch to another method). In Nigeria, where 5 women were enrolled in the study, 2 were only available for 1 interview each. These 2 participants’ interviews were therefore not included in the analysis for this longitudinal, qualitative study, resulting in a total of 9 participants across the 3 countries, and an overall total of 25 interviews, as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Outline of Study Participants |

Study Instruments

Study participants used up to 2 PVRs (or two cycles) for a maximum of six months of use. The 9 women who participated in the in-depth interviews were interviewed 2 to 3 times each: at the end of month one, and then at the end of month three and/or month six of ring use, using specific field guides designed for each month. The first interview explored women’s initial experiences using the ring and their perceptions about the method. The second interview focused on subsequent experiences and perceptions (given the passage of time), using a section of questions identical to those used in the first interview. The third interview dwelt on women’s thoughts about the future of the PVR in their individual countries given their own experiences.

The selection of this layered approach to interviewing was deliberate, as conducting several interviews with a small sample of individuals over time (rather than with a large sample at one time point) gives room for respondents to build upon emerging themes as they make full meaning of their experience with the passage of time. Furthermore, it builds rapport with the study team such that research participants feel comfortable to share insights that otherwise they may have withheld.

Data Collection and Analysis

The interviews were carried out in English in Kenya; in English and/or Pidgin English in Nigeria; and in French in Senegal. In Kenya and Senegal, the interviews were conducted by a study co-investigator based in each country. In Nigeria, the interviews were conducted by a trained research assistant with extensive experience in collecting sexual and reproductive health data. All interviewers were female and had no pre-existing relationships with the study respondents and health facility sites. This approach was deliberately geared toward fostering openness on the part of respondents and, thus, toward granting depth to the interviews. The same interviewers carried out a series of interviews with each participant, therefore, strengthening participant-interviewer rapport over time.

One study participant in Kenya opted not to have her interviews audio-recorded. In this case, the interviews were hand-recorded and transcribed in MS Word. All other interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Following the transcription, the Pidgin English and French transcripts were translated into English. The translations were carried out independently by 2 co-investigators per country who were native speakers of English and of the other languages concerned (French and/or Pidgin English). In each case, where there were any variances, consensus was reached collaboratively by the 2 co-investigators on the final English translation of each transcript.

The final transcripts were in English and were analyzed by 2 co-investigators via a phased process suggested for interpretive phenomenological analysis:16 looking for themes in the first case; connecting the themes; continuing the analysis with other cases; and writing up. A co-investigator commenced the process by reading a first transcript several times, annotating any excerpts that seemed important or interesting. Through subsequent readings of the same transcript, potential themes were identified and made note of, with the understanding that these themes might be modified or eliminated altogether if they did not feature in other transcripts. The emergent themes were listed in a Word document, along with relevant quotes. Themes were identified at “descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual levels.”17 This process was carried out for a single transcript from each study country.

A second co-investigator repeated this process – this time, for all of the study transcripts in each country – using the Word document to orient the analysis. Potential themes in the document were confirmed as actual themes if they permeated the data in each country, and tentative themes which did not prove to be pervasive in the data were dropped. The analysis at this stage also entailed identifying any new themes that had not been readily apparent in the previous transcripts, and going back to those transcripts to see if similar patterns were discernable. This co-investigator then shifted the analysis to analytical/theoretical ordering, attempting to make sense of the connections between themes, and clustering themes that were interconnected and could be viewed as falling within the same larger category. This process involved consulting each of the transcripts repeatedly to ensure that the interpretation of the themes aligned with participants’ narratives, and modifying themes where this was not the case. It also entailed teasing out similarities and dissimilarities in respondents’ accounts. Codes were categorized as major themes if they were identified within the narratives of all 9 participants. Each major theme was then investigated further by continued reading of coded chunks of texts from all interviews within and across countries to distill smaller pockets of meaning (sub-themes) embedded in the overarching themes.

Analysis of the data continued as part of the process of writing up the various themes, as the writing itself helped facilitate the iterative process of “illuminating, strengthening, and thickening the narrative emerging from the analysis.”17 The process of producing subsequent, improved drafts of the paper similarly facilitated the clarity and depth of the analysis.14,17

The kind of reflexive analysis described here is embedded within the interpretive phenomenological approach. It is noteworthy that thematic saturation is inconsistent with the assumptions and values of this sort of reflexive analysis. As Braun and Clarke explain, unlike with neo-positivist approaches to thematic analysis, the reflexive approach

[recognizes] that meaning is generated through interpretation of, not excavated from, data, and therefore judgements about ‘how many’ data items […] are inescapably situated and subjective [.]18

Research Ethics and Consent

Prior to the commencement of the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Population Council (Protocol 562), New York, USA. In addition, relevant research and ethics bodies in Kenya (Kenyatta National Hospital-University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee; and the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation), Nigeria (the Federal Capital Territory Health Research Ethics Committee; and the Institute for Advanced Medical Research and Training), and Senegal (Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé) issued approvals for the study.

Informed consent was received from all study participants (including consent for publishing participants’ anonymized responses), and the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Results

Four overarching themes emerged from the analysis described above. These themes circulated around the unconventionality of the PVR from the perspective of women users across the study countries; the sense of comfort that women gained from opting to use the PVR in particular, over other FP methods; the complex narratives around the consideration that women demonstrate toward their partners in order to ensure that their own use of the PVR is sustainable; and, finally, the conundrums that women grapple with as they prepare to disengage from this method after two cycles of use. Almost invariably, the themes are represented by verbatim quotes from women in each country, to demonstrate their recurrence and pervasiveness in the data. Although the themes are presented in separate sections to maintain clarity and order, there is considerable overlap between the various themes, as is expected in qualitative analysis. We delve into the four key themes in further detail below.

Unconventionality (Newness)

Narratives surrounding the unconventionality of the PVR highlight the use of this new method as a perceived symbol of modernity where women users are concerned. Clients that opted to use the PVR would occasionally refer to the “newness” of the PVR as informing their decision to try it in the first place. Some spoke specifically of the PVR being “new on the market” and alluded to the method being rare, or an import, much like one would describe the latest imported mobile phone or other similar gadgets that often symbolize contemporariness in African urban centers.19 Others merely had their curiosity aroused by the novelty of the method, and were open to experimenting:

[F]irst of all, it is new in the market. So, it was like, wow, let me try it because I have tried the others, but they are not good for me, so I said, maybe this [method] will be the one for me. (Kenya, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

The fact that it’s a new method also influenced my choice because it’s always good to try something new (feminine curiosity). (Senegal, Respondent 2, Interview #1)

[My husband] asks me about this new method and I always tell him that it has come with the White people, and they are testing it to find out whether it is good or bad for Kenyans. (Kenya, Respondent 2, Interview #1)

You know this PVR, this is a new one. This is a new method. Many people don’t know about this PVR. When we [friends] were chatting, I told them that there’s a brand new method. You can’t feel it when it’s inserted. I told them … I told them that there’s a new method now – that the method isn’t available everywhere. It’s hard to get … If you go to an ordinary hospital, you won’t find it. (Nigeria, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

The last two quotes above highlight the connections between “newness” and perceived quality and prestige. In noting that the PVR came into the country “with the White people,” the respondent from Kenya alludes to the fact that this new reproductive technology is an import, and, in African countries, some products imported from the global north are often perceived to be associated with higher quality than those that locally manufactured.20–22 Furthermore, in pointing out that the PVR “isn't available everywhere,’ and is “hard to get,” the respondent from Nigeria highlights the issue of rarity, and the importance of this “limited edition” construction of the PVR in heightening its desirability as a family planning method. In noting the product’s rarity, this respondent demonstrates that contraceptive methods – like other foreign products, serve as a status symbol for some.

However, sometimes, the quest for newness was simply as a result of the fact that clients had tried other methods previously and were not satisfied with them. Thus, some were merely in search of a “new” method that they had not heard of and therefore did not know of anyone who experienced side effects from using it. We elaborate on this point in the next sub-section.

Comfort (Convenient and Women-Controlled)

In selecting the PVR, some women were sometimes simply in search of a family planning method that they perceived to be comfortable to use. Women’s notions of comfort revolved around the PVR’s perceived lack of side effects; the convenience afforded by the method; and the fact that the PVR is user-controlled.

Many women expressed concern over the side effects that they had personally experienced with other methods in the past, or their perceptions of side effects confronted by others:

I thought that [the ring] was something that would really help me, as the ones [methods] that I was using earlier on did not help me that much. Because I once used the injections and bled for three weeks, so I felt like this one had no side effects. … When I was using the injection, that’s what I felt: headaches and cramps. … I thought that [the ring] wouldn’t be so bad such that it would harm my body. So, I chose [it]. (Kenya, Respondent 2, Interview #1)

I just like this method because, you know sometimes … like, I saw my neighbor with this injection they give in the hand; it made her not to be able to lift the hand up. The thing swell up [got swollen]. It does not allow her [to] do any hard work. But me, I can do anything. I can even take my leg up and down and trek [further than] than this junction – it does not do me anything, I will not even feel anything. I just feel confidence with it [the PVR]. I just like it because it is very easy and simple. (Nigeria, Respondent 2, Interview #1)

I was interested in the ring because other methods have too many side effects. Senegal (Senegal, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

Women were less concerned over possible side effects from the PVR, as the ring could simply be removed if such effects occurred. Having some level of control or autonomy over their chosen method (whether for side effect mitigation, or for other reasons) was important to respondents, and the PVR afforded them this opportunity. For respondents, this contrasted with other methods, which were tied both to a provider (without whom a received method could not be terminated) and a time period (which had to elapse before a woman could take action by embarking on the use of another method, as with injectable contraception). All of these circumstances diminished the sense of comfort that women sought from family planning methods, and they viewed the PVR as a solution to their various predicaments:

[I]n the past two years I have used the injections and they are not good for me. I have usually been bleeding throughout. For the pills, I vomit throughout. So, I decided to change and try this new method. … Since I have tried all the others and they are not that good, I said now, this one is not injection: If it is not working with my body, they will just remove it. Now it has no effect in my body. Yeah, that is why I chose it. … Because if I use the injections, unless the three months are over, there is nothing you can remove, but for this one [PVR], if it is not working with my body, then they just remove it. (Kenya, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

Honestly, [the PVR] is better because, even if not for anything, after 3 months, they will check you. Not like those [methods] that they will leave for a long time – even up to one year or two – and it is in your body, and you don’t know what is going on. But this one, after 3 months, you know what you are involved in; they will check you and see what is going on, and they will change it for you [if necessary]. (Nigeria, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

[Explaining why she was interested in the PVR]: Following the explanations of the provider, it’s mainly the fact that this is a method that can be inserted by the woman herself, unlike other methods, where the presence of a provider is required. (Senegal, Respondent 2, Interview #1)

Women’s constructions of comfort also related to convenience – particularly, the convenience of the PVR as a low-maintenance method, and the added advantage of PVR’s positive effect on breast milk supply. As women from all three countries intimated:

It’s easy to use it, especially compared to the pill. You don’t ‘forget’ to take it because it’s always there. (Kenya, Respondent 3, Interview #1)

When [the providers] told us that they [the PVR cycles] were finished, we are not happy, honestly. And everything about this one [PVR] now is easy for us. … Just, you insert it, and you are free. It won’t disturb you and your mind will not be there again. You are free. You want to remove it, it is easy; you want to remove it, it is easy and okay. (Nigeria, Respondent 3, Interview #3)

[I]t’s a safe method, easy to use, and … it doesn’t affect the health of [one’s] child at all, nor sexual intercourse. (Senegal, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

Consideration (Partner Acceptance)

Despite women’s emphasis on their personal needs (including convenience and having control over their method), consideration for their partners’ needs and opinions also formed a key part of their narratives. As demonstrated by accounts in the previous section, women want control over the discontinuation of their method, should it prove problematic. However, the data also show that the needs and opinions of women’s partners are important enough to shape their family planning decisions and strategies. As women do not live in a vacuum, they often opt for a collaborative approach with their partners in arriving their method choice, while also seeking individual control over any needs for method discontinuation:

Before you go into it [choosing a family planning method], you can’t use it only you [by yourself]. You will discuss with your husband when you are going into it. Because if you don’t discuss with your husband and your husband later notices, you will feel somehow [uneasy]. … Before you know [it] … people will be fearing you, [thinking you are in the] occult, or something like that. It is better [for] you [to] discuss so that if you want to go into it, you will know … it is plan[ned] between husband and wife. (Nigeria, Respondent 1, Interview #2)

I had to inform my husband about the method and how it works, and about the fact that the ring wouldn’t affect my breastmilk supply. He was very happy because he had always thought that contraceptives could be passed on into breastmilk and have harmful effects on the baby’s health. (Senegal, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

You know, everything that you do, you must consult your partner. Especially concerning family planning, just in case anything happens. (Kenya, Respondent 1, Interview #3)

Respondents’ accounts revealed another dimension of consideration on the part of women. A primary concern of women was that the use of the PVR might pose an inconvenience for their partners. A recurrent theme in Kenya and Nigeria, specifically, was the fear that partners might feel the PVR during sexual intercourse, and that their sex lives would be hampered by this. As some women revealed, providers played a role in allaying these concerns:

Okay, first of all It was like, you are giving me this one, you are introducing this one to me, now what will happen to my sexual life with my husband? Then [the nurse] answered me that it will not affect, but for sure now I’ve seen it and it has not affected my sexual life. … First of all, for the first day I did not tell him, I waited, I wanted to hear whether he will complain, we went to bed there was no complain then the following day is when I told him, that you know what, I want to show you something. I removed the thing, then I showed it to him and he was like huh! What is this, now? And I told him it is a method of family planning since with the others I’m gaining weight I’m bleeding throughout, so I want to try this one. It was like he was very, very happy. … Because he was complaining … before, he was complaining, since I was having pills throughout, gaining weight, he was complaining, but for this one, he hasn’t complained. (Kenya, Respondent 1, Interview #1)

I asked the nurse whether my husband will be able to feel the ring [during sexual intercourse]. I think it would be a bad thing for my husband to feel the ring because it’ll make him feel uncomfortable. I asked whether the ring can come out, and if it can cause any diseases. (Kenya, Respondent 3, Interview #1)

[The PVR] is easy to [insert] and easy to remove. And when you insert it … you will not feel it, it will not give you any stress to remove it or … you will not even remember that you insert[ed] something. Even when you are meeting [having sexual intercourse] with your husband, you will not feel it, and even your husband will not feel it. It will be as if you are normal. (Nigeria, Respondent 3, Interview #2)

I ask[ed] him [my husband] … ‘Is it [the PVR] disturbing you?’ [If so], [l]et me just put it [at the back of] my mind so … I [can] go and remove it. [He said], ‘No-o.’ He didn’t tell me that I should go and remove it. He just [told] me that he used to feel that there is something there [he could feel it during sexual intercourse]. So, I [said], ‘Okay.’ (Nigeria, Respondent 2, Interview #2)

Conundrums (Limitations of Use)

As mentioned earlier in this paper, the PVR is designed for use by breastfeeding women for a period of up to a year postpartum. The longitudinal nature of the present study permitted an exploration of women’s experiences when they came to the end of their final PVR cycle, and therefore needed to transition to another method. In Kenya and Nigeria in particular, most women faced challenges in disengaging from the PVR – a method that they had become enamored with, and accustomed to:

I was thinking if I drop [discontinue], like, this one [the PVR] now, how am I going to cope again with another one [when] I don’t want another method? I just want to continue with [this] method. So, when that time reach[es] now [to discontinue the PVR], I am saying, how will I do it? (Nigeria, Respondent 3, Interview #2)

I’ve had the […] PVR removed. […] They now gave me the pill[.] I was very … [disappointed]. … I thought of it and said, ‘Ah-ah! I can’t use this tablet-o.’ They now told me I should manage it [make do with the pill]. (Nigeria, Respondent 1, Interview #3)

Now [that I’m at the end of the PVR cycles], I’m totally confused. I don’t know which method to shift to. I was very comfortable with this one [PVR]. But I will talk with the nurse. I’ve not yet decided. The nurses are the ones who will decide for me. (Kenya, Respondent 4, Interview #3)

I’m afraid because, when I gave birth to my first born, I was using injections and I was bleeding so much. Then, the pill makes me puke. So now, I’m afraid. What am I going to use now? I don’t know what to do. (Kenya, Respondent 1, Interview #3)

In describing the difficulties they face in disengaging from the PVR and transitioning to a new method, women also shed light on another conundrum: the narrow family planning method mix in their contexts, which severely limits choice. In Nigeria, for instance, a respondent noted being obligated to take up the pill – a method that she was uncomfortable with – simply because that was what was available. A Kenyan respondent expressed similar despair, given that the readily available methods at her health facility (the pill and the injectable) were not her preferred methods.

Discussion

An in-depth understanding of how and why women receive a new contraceptive is useful for ensuring robust uptake of such new methods, particularly in contexts where the method mix is narrow, contraceptive prevalence rates could be enhanced, and unmet need is high. The three capital cities in which the PVR was introduced under this study are characterized by one or more of these features. The PVR is a contraceptive that women in their first year postpartum can use provided they experience four episodes of breastfeeding a day. Women’s narratives in this study point to a number of key issues that could help inform the design of programs to support other women in African countries in adopting the PVR and other novel contraceptives.

What women’s accounts suggest is that reproductive health products, such as contraceptives, are not necessarily viewed very differently from non-reproductive health products when it comes to their appeal. PVR users’ reasons for selecting this new method were not primarily associated with medical reasons. Often, the PVR appealed to women because it was a new phenomenon on the market, hard-to-get, and – as a further sign of its rarity – imported. These reasons are familiar, but tend to apply to products unrelated to reproductive health. These rationales point to the utility of applying marketing and branding strategies conceived for non-reproductive health items to new contraceptives. This approach could potentially heighten the desirability of new contraceptives being introduced to various contexts for the first time. We also recognize, however, that the participants recruited for this study could be a select group of women who were willing to try new things which might not appeal to all women.

In the same vein, when introducing a new method, highlighting the level of convenience that the latter would afford women would also be important. The study findings demonstrate that convenience is highly prioritized by women seeking a method. As they would with any non-reproductive health product, women are in search of a method that is easy to use, and that does not impose any additional stressors upon their lives. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that the PVR may have different side effects in this population than in others. The most common complaint women have with progestin-only methods is changes in menses. Women who breastfeed at least 4 times a day are generally amenorrheic and, importantly, accept that amenorrhea as natural. By the same token, they are less likely than non-breastfeeding women to experience unscheduled bleeding.

Related to the importance of convenience is the issue of side effects. For women in this study and in other studies (whether Africa-based23 or beyond24,25), perceptions around, and personal experiences of, side effects serve as a deterrent to the uptake of specific methods, and are voiced as a major concern. This calls for thorough family planning counseling around new and existing methods to ensure that myths are dispelled, expectations are grounded in reality/science, and remedies for potential side effects are well understood by women in advance of their becoming users of a particular method.

As the respondents in the present study intimated, “women-controlled” methods are an added advantage for any new family planning methods being developed, in that they lend themselves to prompt and easy discontinuation, should users be dissatisfied with them. However, findings from this study demonstrate that when it comes to women-controlled methods, men still matter. The introduction of such methods to new settings must therefore lend attention to the realities of gender relations in the contexts concerned, embedding the needs of users’ partners into the approach.

Despite the foregoing, we are cognizant of the fact that the women in this study form a select group in that they all informed their partners about their use of family planning. We recognize that many women might prefer to use family planning covertly, without the involvement of their partners, for various reasons. Given this reality, it would be useful to plan for covert use by some women and design appropriate program strategies that will support such women in their contraceptive journeys.

The narratives derived from this study are a reminder that, in introducing the PVR in particular to new settings, we must begin with the end in mind. Women’s transition to a new method after completing the PVR cycles must form part of the thinking right from the beginning. Women require support and family planning counseling well before the end of their final PVR cycle in order to make informed decisions that they are comfortable with, within the context of available methods in their countries.

As previously mentioned, this study was part of a larger acceptability study involving quantitative and qualitative data collection from PVR users. The quantitative study relied on a priori categories for exploring women’s experiences, including ease and comfort, experience of ring expulsion, experience of sexual intercourse with the ring inserted, and partner support.

Conversely, the approach of the current study provided an opportunity for women to share their experiences in their own words, without the restriction of pre-determined categories. It also encouraged women to provide in-depth descriptions and explanations of these experiences. As a result, information that could not have been generated via the quantitative survey was gleaned through the qualitative interviews.

For example, by refraining from determining in advance what women’s reactions to, and experiences with, a new contraceptive product would be, the interpretive phenomenological approach fostered the emergence of important, unanticipated issues, such as the notion of novelty, and how it might shape the acceptability of new contraceptive technologies. Furthermore, this approach helped to broaden understanding of key concepts which could affect the acceptability of the PVR from the users’ perspective. For instance, in the earlier quantitative study, women’s sense of ease and comfort with the PVR was pre-constructed around the mechanics of using it: eg, PVR expulsion experiences, and ease of PVR insertion and removal. The present study involved privileging women’s own meaning-making with regard to their PVR use, resulting in an enhanced understanding of ease and comfort from the perspective of PVR users. It revealed women’s desire to have some level of control over their method (ie, being able to discontinue the method whenever they wanted), and for their method to serve multiple purposes, if possible (eg, pregnancy prevention coupled with an improvement in breastmilk supply).

As a further example, with regard to partner support, the earlier quantitative study focused on whether women’s partners could feel the PVR during sexual intercourse, and whether the frequency of sex and sexual pleasure itself had been affected by PVR use. The present study enriched the quantitative findings, permitting entry into women’s personal and social worlds, and demonstrating the intricate negotiations that women undertake in order to settle into the use of a method: keeping their partners informed about their method choice; testing out the use of the PVR during intercourse to ensure their partners feel comfortable with it; checking in with their partners periodically to ensure that no form of discomfort has arisen; and being willing to change their method due to partner discomfort. These are equally important issues which pre-determined categories (such as whether women’s partners could feel the ring, or whether the PVR had affected the frequency with which women and their partners engaged in sexual intercourse) were unable to capture.

Conclusion

The progesterone vaginal ring is a new contraceptive format that enhances a woman’s control over its use, and that could help expand the method mix in African countries. This contraceptive can be used by women in their first year postpartum as long as they breastfeed at least 4 times a day. The current study offers in-depth insight into women’s experiences of choosing and using this contraceptive, illuminating the facilitators and barriers associated with this process. The findings explain why some women take up the PVR, why they continue with it, and the issues they confront in transitioning from it. Such information could be helpful for the effective tailoring of family planning counseling to this contraceptive, for product marketing, and, ultimately, for the uptake of this method. Formative data on women’s perceptions of, and reactions to, the PVR should feed into country preparation processes prior to its introduction into new country contexts.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for their generous support of the research; and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, as well as AmplifyChange for their support for writing this paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Ross JA, Winfrey WL. Contraceptive use, intention to use and unmet need during the extended postpartum period. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27(1):20–27. doi:10.2307/2673801

2. Moore Z, Pfitzer A, Gubin R, Charurat E, Elliott L, Croft T. Missed opportunities for family planning: an analysis of pregnancy risk and contraceptive method use among postpartum women in 21 low-and middle-income countries. Contraception. 2015;92(1):31–39. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.03.007

3. RamaRao S, Ishaku S, Liambila W, Mane B. Enhancing contraceptive choice for postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa with the progesterone vaginal ring: a review of the medicine. Open Access J Contracept. 2015;6:117–123. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S55033

4. Dev R, Kohler P, Feder M, Unger JA, Woods NF, Drake AL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of postpartum contraceptive use among women in low and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2019;16:154. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0824-4

5. Kennedy KI, Rivera R, McNeilly AS. Consensus statement on the use of breastfeeding as a family planning method. Contraception. 1989;39(5):477–496. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(89)90103-0

6. Brache V, Payán LJ, Faundes A. Current status of contraceptive vaginal rings. Contraception. 2013;87(3):264–272. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.037

7. Sivin I, Díaz S, Croxatto HB, et al. Contraceptives for lactating women: a comparative trial of a progesterone-releasing vaginal ring and the copper T 380A IUD. Contraception. 1997;55(4):225–232. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(97)00008-5

8. Population Council. Progesterone Vaginal Ting: Beneficial Role in Supporting Breastfeeding. New York: Population Council; 2016. Available from: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2016RH_PVRSupportBreastfeeding.pdf.

9. Sitruk-Ware R, RamaRao S, Merkatz R, Townsend J. Risk of pregnancy in breastfeeding mothers: role of the progesterone vaginal ring on birth spacing. Eur Med J Reprod Health. 2016;2(1):66–72.

10. RamaRao S, Obare F, Ishaku S, et al. Do women find the progesterone vaginal ring acceptable? Findings from Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. Stud Fam Plann. 2018;49(1):71–86. doi:10.1111/sifp.12046

11. RamaRao S, Clark H, Rajamani D, et al. Progesterone Vaginal Ring: Results of a Three-Country Acceptability Study. New York: Population Council; 2015.

12. Ulin P, Robinson ET, Tolley EE, McNeill ET. Qualitative Methods: A Field Guide for Applied Research in Sexual and Reproductive Health. Research Triangle Park: Family Health International; 2002.

13. Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Smith JA, editor. Qualitative Psychology. A Practical Guide to Research Methods. London: Sage; 2003:51–80.

14. Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage; 2009.

15. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage Publications; 1994.

16. Smith JA, Osborn M.Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In: Smith JA, editor. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. Sage Publications, Inc; 2003; 51–80.

17. Shallcross R, Dickson JM, Nunns D, Taylor K, Kiemle G. Women’s experiences of vulvodynia: an interpretive phenomenological analysis of the journey toward diagnosis. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:961–974. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1246-z

18. Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exercise Health. 2019;1–16. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

19. Masvawure T. ‘I just need to be flashy on campus’: female students and transactional sex at a university in Zimbabwe. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(8):857–870. doi:10.1080/13691050903471441

20. Chepchirchir J, Leting M. Effects of brand quality, brand prestige on brand purchase intention of mobile phone brands: empirical assessment from Kenya. Int J Manage Sci Bus Admin. 2015;1(11):7–14. doi:10.18775/ijmsba.1849-5664-5419.2014.111.1001

21. Ifediora CU, Ugwuanyi CC, Ifediora RI. Perception and patronage of foreign products by consumers in Enugu, Nigeria. Int J Econ Commerce Manage. 2017;5:12.

22. Kalicharan HD. The effect and influence of country-of-origin on consumers’ perception of product quality and purchasing intentions. Int Bus Econ Res J. 2014;13:5.

23. Machiyama K, Huda FA, Ahmmed F, et al. Women’s attitudes and beliefs towards specific contraceptive methods in Bangladesh and Kenya. Reprod Health. 2018;15:75. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0514-7

24. Archer DF, Merkatz RB, Bahamondes L, et al. Efficacy of the 1-year (13-cycle) segesterone acetate and ethinylestradiol contraceptive vaginal system: results of two multicentre, open-label, single-arm, Phase 3 trials. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(8):e1054–e1064. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30265-7

25. Merkatz RB, Plagianos M, Hoskin E, et al. Acceptability of the Nestorone®/ethinyl estradiol contraceptive vaginal ring: development of a model; implications for introduction. Contraception. 2014;90(5):514–521. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.05.015

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.