Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 13

Caregiver perspective on pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: medication satisfaction and symptom control

Authors Fridman M , Banaschewski T , Sikirica V, Quintero J , Erder MH, Chen KS

Received 6 September 2016

Accepted for publication 14 November 2016

Published 13 February 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 443—455

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S121639

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Moshe Fridman,1 Tobias Banaschewski,2 Vanja Sikirica,3 Javier Quintero,4 M Haim Erder,3 Kristina S Chen5

1AMF Consulting, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim of the University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany; 3Global Health Economics Outcomes Research and Epidemiology, Shire, Wayne, PA, USA; 4Psychiatry Department, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain; 5Global Health Economics Outcomes Research and Epidemiology, Shire, Lexington, MA, USA

Abstract: The caregiver perspective on pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) study (CAPPA) was a web-based, cross-sectional survey of caregivers of children and adolescents (6–17 years of age) with ADHD and was conducted in 10 European countries. CAPPA included caregiver assessments of global medication satisfaction, global symptom control, and satisfaction with ADHD medication attributes. Overall, 2,326 caregiver responses indicated that their child or adolescent was currently receiving ADHD medication and completed the “off medication” assessment required for inclusion in the present analyses. Responses to the single-item global medication satisfaction question indicated that 88% were satisfied (moderately satisfied to very satisfied) with current medication and 18% were “very satisfied” on the single-item question. Responses to the single-item global symptom control question indicated that 47% and 19% of caregivers considered their child or adolescent’s symptoms to be “controlled” or “very well controlled”, respectively. Significant variations in response to the questions of medication satisfaction and symptom control were observed between countries. The correlation between the global medication satisfaction and global symptom control questions was 0.677 (P<0.001). Global medication satisfaction was significantly correlated (P<0.001) with all assessed medication attributes, with the highest correlations observed for symptom control (r=0.601) and effect duration (r=0.449). Correlations of medication attributes with global symptom control were generally lower than with global medication satisfaction but were all statistically significant (P<0.001). CAPPA medication satisfaction and symptom control were also significantly correlated (P<0.001) with symptom control as based on the ADHD-Rating Scale-IV symptom score and the number of bad days per month when on medication. In conclusion, caregiver responses in this European sample suggest that current treatment could potentially be improved. The observed correlations of global medication satisfaction with global symptom control and other CAPPA assessments, including medication attributes, provide support for the inter-connectivity of the medication satisfaction and symptom control.

Keywords: ADHD, CAPPA, child/adolescent, Europe, medication attributes

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. Alongside these core features, the diagnosis of ADHD requires impairment of social, academic, or occupational functioning in 2 or more settings – generally at home and school.1 The effects of ADHD on home life,2–4 academic functioning,5,6 and family relationships2,3 can have a substantial impact on quality of life (QoL). Ratings of health-related QoL (HRQoL) in children and adolescents with ADHD have been shown to be significantly lower than in their peers without ADHD and in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus, and, when self-reported, were found to be similar to those observed in patients with newly diagnosed cancer or cerebral palsy.7,8 Furthermore, high rates of comorbidities, including learning disabilities, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety, and mood disorders, add to the burden of illness experienced by individuals with ADHD.9,10

In addition to directly affecting children and adolescents with the condition, ADHD can also adversely impact the daily lives of their parents or caregivers and other family members. The impact of ADHD on the academic and social functioning of the individual, and on personal relationships, adds to the burden of family, friends, and others in day-to-day contact with the person with the condition.11–13 The views of parents and caregivers on available treatment options for their children or adolescents with ADHD are important determinants in the perceived success of a particular therapy.14,15 Individuals with ADHD who do not receive treatment during childhood or adolescence have been reported to have poorer long-term outcomes than those who received treatment.16

Treatment for ADHD includes behavioral and pharmacological interventions. Behavioral interventions can help children and adolescents to improve their social communication, functional living skills, and methods to cope with their symptoms. Pharmacotherapy utilizes stimulant or non-stimulant medications to reduce core symptoms of ADHD.17,18 It is important to note, however, that there is considerable variation in ADHD diagnostic and treatment practices in different countries.19–21

The caregiver perspective on pediatric ADHD study (CAPPA) was designed to evaluate the caregivers’ perspectives on ADHD-related unmet needs of children and adolescents with ADHD, and of the caregivers themselves. The first phase of CAPPA, which has been reported previously,22 comprised a series of semi-structured interviews with 38 caregivers of children and adolescents with ADHD across 8 European countries and reported that medications do generally improve symptoms but that the caregiver burden remains substantial. The second phase of the study was a web-based, cross-sectional survey, completed between November 2012 and April 2013 by caregivers of children and adolescents with ADHD in 10 European countries based on the concepts reported in the first phase. Overall, 3,688 CAPPA questionnaires were completed on behalf of children and adolescents with a mean age at diagnosis of ADHD of 6.9 years, 80% of whom were males and 78% of whom were receiving ADHD pharmacotherapy at the time of the survey.23 We now report results of a single-item assessment of global medication satisfaction from the caregivers’ perspective. We also evaluate the relationships of CAPPA global medication satisfaction with a single-item assessment of global symptom control, with caregivers’ perspectives of specific attributes of medications, and with other clinical and demographic characteristics, by conducting correlation analyses and conceptual model validation using mediation analyses.

Methods

The methodology of this cross-sectional survey of caregivers of children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD has been reported previously.23 The CAPPA survey was conducted online between November 2012 and April 2013 in 10 countries in Europe (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and UK). Data from Denmark, Finland, and Norway were pooled because of small sample sizes and are referred to as “other Nordic countries”. The study was reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (IRB), MaGil IRB, and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants in the UK completed an online consent form before being directed to the CAPPA survey. In other countries, a waiver of consent form was granted by the IRB and participants were provided with contact information in the event of any concerns or difficulties encountered during or after the survey.

Participants

As described in a prior publication,23 3,688 caregivers of 2,932 male (79.5%) and 756 female (20.5%) children and adolescents aged 6–17 years (mean age ± standard deviation, 11.5±3.2 years) completed the CAPPA survey. In order to minimize recall bias, the present analyses of CAPPA global medication satisfaction and global symptom control included responses only from caregivers of those who were receiving ADHD medication at the time of the survey (current treatment); those who had received medication within the 6 months preceding the survey (recent treatment) were excluded. Caregivers were also questioned about “off ADHD medication” periods, and only caregivers who responded to these off-medication period questions were included in the present analyses. Off medication was defined as the child forgot to take medication; the child intentionally chose not to take medication (eg, on holidays or weekends); or at times of the day when the effect of the last dose of medication would be expected to have worn off.

Measures

Single-item assessments of medication satisfaction and symptom control

For medication satisfaction, caregivers were asked, “Thinking about [child’s name]’s present medication(s), how would you define your level of overall satisfaction with this medication?” Responses were scored using a 7-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied) in order to provide symmetry and balance in response options.

For symptom control, caregivers were asked, “Thinking about [child’s name]’s present medication(s), how well controlled are his/her ADHD/attention-deficit disorder symptoms?” As degradations of symptom control may be difficult to separate with a 7-point Likert scale, responses were based on a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 (not at all controlled) to 5 (very controlled).

To test the ability of these single-item questions to collect appropriate response options, the global symptom control and medication satisfaction assessments were evaluated for ceiling and floor effects.

Specific medication attributes

Using the same 7-point Likert response scale as used for the CAPPA global medication satisfaction measure, caregivers were asked about their level of satisfaction with 8 medication attributes: 1) how often the child has to take the tablets (dose frequency); 2) tablet size; 3) effect duration; 4) time for the tablets to start working (speed of onset); 5) control of symptoms/behaviors (symptom control); 6) potential adverse events; 7) potential for abuse/misuse; and 8) potential for dependence/addiction. A total medication attributes satisfaction (TMAS) score was calculated for each caregiver by summing the responses for the 8 attributes.

Other clinical and demographic assessments

ADHD symptoms were also assessed using the ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS-IV), a widely used, validated, and standardized instrument comprising individual items for 18 symptom domains which, when summed, produce the ADHD-RS-IV total symptom severity score.24,25 Caregivers were asked to complete the ADHD-RS-IV for when the child or adolescent was “on medication” and “off medication”. The ADHD-RS-IV total score when on medication was used as an indication of symptom control. The ADHD-RS-IV total score when off medication was used as a proxy for baseline disease severity in mediation modeling because it was not possible to obtain a reliable estimation of baseline disease severity at the time of the survey.

The number of “bad” days per month that the child or adolescent experienced while receiving ADHD medication was assessed by 2 questions: 1) “Children sometimes experience difficult or ‘bad’ days, even when taking medication. On average, how many days per month does the child have ‘bad’ days? Please give your best estimate” and 2) “Out of those ‘bad’ days your child has per month, how many happen when on medication? Please give your best estimate”.

Caregivers categorized medication use as “daily/always”, “as needed”, or “never used for weekends/holidays”. The frequency of medication use was adopted as a proxy for medication adherence in mediation modeling.26 Prescription drug use was classified as high frequency if reported as “daily/always” by caregivers together with an adherence rate ≥80% on weekdays and ≥50% on average for weekends/holidays; lower adherence levels and “as needed” prescription drug use on weekdays were classified as low frequency.

The total number (0, 1, 2, or 3+) and types of comorbidities are reported elsewhere.23,26 Comorbidities were classified as learning difficulties, motor-coordination disorder, or speech/language disorder; conduct disorder or ODD; anxiety; and autism or Asperger syndrome.

Mediation modeling

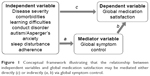

Food and Drug Administration guidelines were adopted for the analysis of self-reported data,27 and mediation analyses were conducted to investigate whether the key independent variables of off-treatment ADHD-RS-IV total score (a proxy for disease severity), the presence of comorbidities, learning difficulties, conduct disorder, autism/Asperger’s syndrome, anxiety and sleep disorder, and frequency of medication use (a proxy for adherence) influenced results of the CAPPA global medication satisfaction measure directly or indirectly via CAPPA global symptom control. A direct effect describes the relationship between global medication satisfaction and the independent variable when the mediator variable (global symptom control) remains unaltered. An indirect effect describes how much global medication satisfaction would change when the global symptom control mediator variable changes by a value equivalent to that required to elicit the direct effect.

When testing for mediation, a series of 4 sets of regression analyses are recommended.28 The first examines the correlation between the independent variables and the dependent variable (in this case, global medication satisfaction), the second between the independent variables and the mediator variable (global symptom control), and the third between mediator variable and the dependent variable. Assuming that these relationships are shown to be statistically significant, then multiple regression analyses may be conducted to examine whether the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variables is direct or indirect.

A linear model was used to estimate the natural (ie, allowing for between-participant variation in the level of the mediator) direct effect and indirect effect. The direct effect expresses how much global medication satisfaction would change when the independent variables change by a specified amount, but the mediator variable (global symptom control) remains unaltered. The indirect effect expresses how much global medication satisfaction would change when the mediator variable (global symptom control) changes by a value equivalent to that required to elicit the direct effect. The total effect is the sum of the direct and indirect effects (Figure 1). The specification of the mediation models and decomposition of effects were based on the publication by Valeri and Vanderweele,29 who expanded mediation model specifications to allow for testing of the interaction between independent variables and the mediator.

To obtain symmetric distributions for global medication satisfaction, and hence allow the use of ordinary least-squares regressions, the lowest 4 satisfaction levels of “very dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied”, “moderately dissatisfied”, and “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” were combined to a single “not satisfied” level, resulting in a 4-point scale (1= “not satisfied” to 4= “very satisfied”). Similarly, for global symptom control, the 2 lowest control levels (“a little controlled” and “not at all controlled”) were combined, resulting in a 4-point scale (1= “no control” to 4= “very controlled”).

Country, child/adolescent age and sex, family ADHD status (ie, whether other family members have ADHD), caregiver relationship to child/adolescent, caregiver work status, caregiver responsibility (eg, sole responsibility), caregiver marital status, and caregiver education level were controlled for as covariates. The number of children/adolescents in the caregiver’s household and the caregivers’ sex were non-significant predictors of both global medication satisfaction and global symptom control and were, therefore, removed. When estimating the effect associated with each specific characteristic, all other characteristics were entered in the model as controls.

Statistical analyses

Pooled descriptive statistics are provided for variables (other than country) cross-tabulated by medication satisfaction and by global symptom control levels. Spearman’s correlations and non-zero correlation test P-values are presented for continuous, ordinal, and binary variables, and χ2 test P-values for nominal multi-level variables. All statistical tests were 2-sided with significance pre-determined as P<0.05. There was no adjustment for multiple testing.

Mediation models were fitted separately for each baseline and treatment characteristic. The natural direct effects, indirect effects, and total effects are reported along with 95% confidence intervals using the delta method. Whereas the use of the bootstrapping technique for deriving standard error is recommended when the sample size is small,30 for larger sample sizes, the delta method was preferred for reasons of computational efficiency.29

Results

Participants

Of 3,688 caregivers who responded to the CAPPA survey, 2,890 reported current ADHD medication use, usually a psychostimulant (82.8%) and usually as monotherapy (75.3%).23 The remainder (n=798) reported no current medication for ADHD, but that medication had been taken recently (within the past 6 months). In total, 2,326 caregivers completed the “off-medication” question and were included in the present analyses of CAPPA global medication satisfaction, global symptom control, and satisfaction with medication satisfaction.

CAPPA global medication satisfaction and global symptom control

In total, 88% of caregiver responses to the single-item CAPPA global medication satisfaction assessment indicated some degree of satisfaction (from moderate to very) with current ADHD medication; 18% of caregivers were “very satisfied” (Figure 2A). The remaining 12% of responses ranged from neither satisfied nor dissatisfied to very dissatisfied. There was statistically significant variation in caregivers’ responses to the CAPPA global medication satisfaction assessment across countries (P<0.001, Figure 2A). Satisfaction (moderate to very) was reported by at least 90% of respondents in France, Germany, and Sweden; the highest rates of dissatisfaction were reported in the Netherlands (18%) and the UK (16%) (Figure 2A).

Results from the single-item CAPPA global symptom control assessment indicated that two-thirds of caregivers of current-medication users thought that their child or adolescent’s symptoms were “controlled” (47%) or “very controlled” (19%) (Figure 2B); only 6% of caregivers reported that symptoms were little/not controlled. There was statistically significant variation in caregivers’ responses to the CAPPA global symptom control measure across countries (P<0.001). Symptoms were reported to be “very controlled” in 40% of cases in Sweden but in only 7% in the UK; the highest levels of little/no symptom control were observed in the Netherlands (11%) and the UK (10%).

Caregiver response rates for both the CAPPA global medication satisfaction and global symptom control single-item questions were 100% (N=2,326). There was no floor effect for either question with only 0.7% responding to being “very dissatisfied” and 1.4% reported being “dissatisfied” to the CAPPA global medication satisfaction question, while 0.8% indicated that symptoms were “not controlled” to the CAPPA global symptom control question. The ceiling effect was 18% for global medication satisfaction and 19% for global symptom control.

Satisfaction with medication attributes

Proportions of caregivers who reported some degree of satisfaction (somewhat to very satisfied) with medication attributes were tablet size, 76.0%; symptom control, 75.6%; time to onset, 72.3%; effect duration, 69.6%; dose frequency, 70.1%; perceived adverse effects, 51.8%; perceived dependence/addiction potential, 46.0%; and perceived abuse/misuse potential, 42.9% (Figure 3). Conversely, caregivers were most dissatisfied (somewhat to very dissatisfied) with perceived adverse events (26.6%), abuse/misuse potential (21.4%), and effect duration (17.5%) of ADHD medications.

Correlations between CAPPA outcomes

There was a positive and statistically significant correlation (r=0.677; P<0.001) between the CAPPA assessments of global medication satisfaction and global symptom control (Table 1). With regard to caregivers’ satisfaction with individual medication attributes, global medication satisfaction was strongly correlated with the attribute of symptom control (r=0.601), moderately correlated with effect duration (r=0.449) and speed of onset (r=0.418), and was statistically significantly correlated with all individual medication attributes (P<0.001). CAPPA global medication satisfaction was also significantly and moderately correlated with the overall TMAS rating (r=0.487, P<0.001). Caregivers’ assessment of global medication satisfaction exhibited statistically significant (P<0.001) but weak negative correlations with symptom control based on the ADHD-RS-IV total score while on medication (r=−0.287) and bad days per month on medication (r=−0.232).

Correlations between the satisfaction with individual medication attributes and the global symptom control measure were lower than the equivalent correlations with global medication satisfaction, but followed a similar pattern (Table 1). Of the individual medication attributes, CAPPA global symptom control was moderately correlated with the attribute of symptom control (r=0.504, P<0.001) and weakly correlated with effect duration (r=0.348, P<0.001) and speed of onset (r=0.328, P<0.001). Correlations between CAPPA global symptom control and the remaining medication attributes, including TMAS, were also statistically significant (P<0.001). Statistically significantly (P<0.001) weak and negative correlations were observed between the CAPPA global symptom control and symptom control based on the ADHD-RS-IV score while on medications (r=−0.301) and bad days per month on medication (r=–0.239; Table 1).

Mediation modeling

Correlations and associations between global medication satisfaction and clinical and demographic covariates are presented in Table 2. Very weak (r<0.2) but statistically significant (P<0.05) correlations with global medication satisfaction were observed for the following independent variables: ADHD severity proxy (off-treatment ADHD-RS-IV); number of comorbidities specifically grouped conduct disorder or ODD, anxiety and sleep disorder; and treatment adherence proxy (frequency of medication). Other covariates associated with global medication satisfaction were caregiver relationship (with fathers more satisfied than mothers) and caregivers’ marital status (with married caregivers more satisfied than single or divorced caregivers).

Correlations and associations between global symptom control and covariates are presented in Table 3. Very weak (r<0.2) but statistically significant correlations were observed for: ADHD severity proxy, number of comorbidities, specifically with conduct disorder or ODD, sleep disorder, and anxiety. Other covariates associated with global symptom control were younger age of child/adolescent, caregiver’s relationship (with fathers reporting better symptom control compared with mothers), married caregivers, and caregivers with a university-level education.

In mediation analyses, a weak, negative and statistically significant indirect effect (r=−0.2, P<0.0003) per 10-point increase (worsening) in ADHD severity proxy on global medication satisfaction was observed; the direct effect was non-significant (Table 4). This suggests that the negative effect of ADHD severity on global medication satisfaction is manifested through the detrimental effect of increased ADHD severity on global symptom control. In contrast, a very weak but statistically significant (r=0.12, P=0.0002) direct effect of the frequency of medication use on medication satisfaction was detected. There were statistically significant (P<0.05) indirect and direct effects of the presence of at least 3 comorbidities compared with no comorbidities on global medication satisfaction, with conduct disorder/ODD also statistically significant for both the direct and indirect effects. A statistically significant total effect of anxiety on global medication satisfaction was observed, otherwise the impacts of other common comorbidities (learning difficulties/motor-coordination disorder/speech or language disorder, autism/Asperger syndrome, and sleep disorder) were non-significant.

Discussion

The CAPPA survey was designed to describe, from the caregivers’ perspective, the unmet needs of children and adolescents with ADHD as well of the caregivers who care for them. A key element of the CAPPA survey was the single-item global medication satisfaction measure of treatment success from the caregivers’ perspective. Internal and external support for the validity of the global medication satisfaction measure was provided by significant correlations with the single-item assessment of symptom control, assessments of satisfaction with individual medication attributes, ADHD-RS-IV score when on medication, and bad days per month when on medication. CAPPA medication satisfaction responses indicated that most caregivers were not completely satisfied with the ADHD pharmacotherapy received by their child or adolescent; adverse events and perceived abuse/misuse potential caused the highest levels of dissatisfaction. Thus, the CAPPA medication satisfaction assessment demonstrated medication-related unmet need in this European sample of caregivers of children and adolescents with ADHD.

As single items, assessed using simple Likert scales, the CAPPA assessments of medication satisfaction and symptom control were intended to be quick and simple for caregivers to use, and a 100% completion rate suggests that this was the case. The small number of caregivers whose responses were at the dissatisfied end of the global medication satisfaction scale suggests that the number of Likert scale options could be reduced from 7 to 5 with no meaningful loss of resolution. Responses to the CAPPA global medication satisfaction assessment demonstrated that >40% of caregivers were either not satisfied or only moderately satisfied, and <20% were very satisfied. Similarly, 34% of responses to the CAPPA symptom control assessment rated symptom control as little/not controlled or only moderately controlled, and <20% reported that symptoms were “very controlled”. These results indicate that, from the caregivers’ perspective, medication satisfaction and symptom control are often less than optimal.

This analysis of CAPPA data also provides insight into caregivers’ views on specific attributes of ADHD medications. More than half of the responses expressed some degree of satisfaction (somewhat to very satisfied) with tablet size, symptom control, speed of onset, effect duration and dose frequency, although <15% reported that they were very satisfied with any of the attributes examined. The highest levels of dissatisfaction (somewhat to very dissatisfied) were reported for adverse events and perceived abuse/misuse potential, demonstrating that safety-related attributes of ADHD medications are a common cause for concern among caregivers.

The correlation between the CAPPA global assessments of medication satisfaction and symptom control suggests that these measures are closely related. Inspection of the strength of the correlations between the CAPPA global assessments of medication satisfaction and symptom control with individual medication attributes reveals that, while the correlations were stronger in all cases for global medication satisfaction than for global symptom control, their rank orders were very similar. Of the medication attributes examined, satisfaction with symptom control and effect duration were most closely associated with global medication satisfaction and global symptom control outcomes. Statistically significant correlations between CAPPA measures provide internal support for the validation of the CAPPA global medication satisfaction measure. External validation of the CAPPA global medication satisfaction measure was provided by the statistically significant correlation with symptom control based on the ADHD-RS-IV symptom score when on medication.

Although there are differences between the single-item CAPPA global outcomes and multi-domain patient-reported outcome measures, we adopted the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for the analysis of self-reported data and conducted mediation analyses to investigate whether key independent variables influenced the results of the global medication satisfaction assessment directly or indirectly via global symptom control. These analyses detected a negative impact of ADHD severity on caregivers’ perception of medication satisfaction that was indirectly mediated via global symptom control. In contrast, mediation analyses suggested that the effect of the frequency of medication use on medication satisfaction was direct. The number of comorbidities and comorbid conduct/ODD influenced caregivers’ perception of medication satisfaction both directly and indirectly via symptom control.

Given that CAPPA provided the caregivers’ perspective, it was to be expected that some of the characteristics of caregivers would be associated with global medication satisfaction outcomes, and statistically significant correlations with the caregiver’s relationship with the child or adolescent (fathers were proportionally less dissatisfied than mothers, P=0.008) and the caregiver’s marital status (married caregivers were proportionally more satisfied than those reported as being single or divorced, P=0.041) demonstrated that is was the case. In contrast, non-significant associations were observed between the CAPPA global medication satisfaction measure and the highest education level (P=0.297) and work status (P=0.158) of caregivers, and a diagnosis of ADHD on other family members (P>0.1).

Strengths of CAPPA are that a large number of caregivers were surveyed in a real-world setting in 10 European countries, and the results of the analysis demonstrate that the impact of ADHD, both on individuals with the condition and on their caregivers, remains substantial. In addition, with the global medication satisfaction question, CAPPA has introduced a single-item assessment of treatment success from the caregivers’ perspective.

Limitations

As described previously,23 this study does have a number of limitations. These include the selection bias introduced by the convenience sampling methodology employed and, because CAPPA data represent the caregivers’ perspective, it may be prone to reporting or recall bias, or be influenced by the respondents’ understanding of ADHD or by cultural factors. While correlations with other CAPPA assessments provide internal validation of the single-item questions of medication satisfaction and symptom control, it is acknowledged that few of these assessments are externally validated, nor were their measurement properties formally assessed, although CAPPA global medication satisfaction was significantly correlated with the well-characterized and accepted ADHD-RS-IV total symptom score (when on medication). It is also acknowledged that 2 of the outcomes used in the mediation analysis (baseline ADHD severity and medication adherence) were based on indirect assessments. Furthermore, because regional quotas were not imposed, the results, although representative of the region, may be under-representative of each individual country, and the heterogeneity in the pooled dataset resulting from the different national sample populations represents an important limitation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, caregiver responses in this European sample suggest that current treatment could potentially be improved. The observed correlations with global symptom control and other CAPPA assessments provide support for the inter-connectivity of the medication satisfaction and symptom control.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by Shire Development, LLC. Under the direction of the authors, Lisa Tatler, of Caudex Medical, Oxford, UK, and Eric Southam and Richard White of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, provided writing assistance for this publication. Editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copy editing, and fact checking was also provided by Caudex and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Magdalena Harrington and Caleb Bliss from Shire Development LLC and Antonia Panayi from Shire International GmbH also reviewed and edited the manuscript for scientific accuracy. Shire International GmbH provided funding to Caudex and Oxford PharmaGenesis for support in writing and editing this manuscript.

Disclosure

M Fridman is an employee of AMF Consulting and serves as a paid consultant for Shire. MH Erder and V Sikirica were employees of, and owned stock/stock options in, Shire at the time of the study. T Banashewski has served in an advisory or consultancy role for Hexal Pharma, Lilly, Medice, Novartis, Otsuka, Oxford Outcomes (now ICON), PCM Scientific, Shire, and Vifor Pharma. He has received conference attendance support and conference support or speaker’s fees from Lilly, Medice, Novartis, and Shire. He is/has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Lilly, Shire, and Vifor Pharma. The present work is unrelated to the above-mentioned grants and relationships. J Quintero is a speaker or member of advisory boards for FEAADAH, Shire, Eli Lilly, Grünenthal, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and has an unrestricted research grant from Otsuka. KS Chen is an employee of, and owns stock/stock options in, Shire. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. | ||

Cussen A, Sciberras E, Ukoumunne OC, Efron D. Relationship between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and family functioning: a community-based study. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(2):271–280. | ||

Davis CC, Claudius M, Palinkas LA, Wong JB, Leslie LK. Putting families in the center: family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(8):675–684. | ||

Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e541–e547. | ||

Holmberg K, Bolte S. Do symptoms of ADHD at ages 7 and 10 predict academic outcome at age 16 in the general population? J Atten Disord. 2014;18(8):635–645. | ||

Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE Jr, Molina BS, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(1):27–41. | ||

Varni JW, Burwinkle TM. The PedsQL as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:26. | ||

Coghill D, Hodgkins P. Health-related quality of life of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus children with diabetes and healthy controls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(3):261–271. | ||

Taurines R, Schmitt J, Renner T, Conner AC, Warnke A, Romanos M. Developmental comorbidity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2010;2(4):267–289. | ||

The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1073–1086. | ||

Chen JY, Clark MJ, Chang YY, Liu YY, Chang CY. Factors affecting perceptions of family function in caregivers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(3):165–175. | ||

Escobar R, Soutullo CA, Hervas A, Gastaminza X, Polavieja P, Gilaberte I. Worse quality of life for children with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, compared with asthmatic and healthy children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e364–e369. | ||

Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(Suppl 1):i2–i7. | ||

Rothenberger A, Becker A, Breuer D, Dopfner M. An observational study of once-daily modified-release methylphenidate in ADHD: quality of life, satisfaction with treatment and adherence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(Suppl 2):S257–S265. | ||

Gortz-Dorten A, Breuer D, Hautmann C, Rothenberger A, Dopfner M. What contributes to patient and parent satisfaction with medication in the treatment of children with ADHD? A report on the development of a new rating scale. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(Suppl 2):S297–S307. | ||

Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 2012;10:99. | ||

NICE. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Diagnosis and manageof ADHD in children, young people and adults. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 72. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg72/resources/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-diagnosis-and-management-975625063621. 2008 (includes 2016 updates). Accessed November 30, 2016. | ||

Popper CW. Antidepressants in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(Suppl 14):14–29; discussion 30–31. | ||

Hinshaw SP, Scheffler RM, Fulton BD, et al. International variation in treatment procedures for ADHD: social context and recent trends. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):459–464. | ||

Seixas M, Weiss M, Muller U. Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(6):753–765. | ||

Setyawan J, Fridman M, Grebla R, Harpin V, Korst LM, Quintero J. Variation in presentation, diagnosis, and management of children and adolescents with ADHD across European countries. J Atten Disord. Epub 2015 Aug 5. | ||

Sikirica V, Flood E, Dietrich CN, et al. Unmet needs associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in eight European countries as reported by caregivers and adolescents: results from qualitative research. Patient. 2015;8(3):269–281. | ||

Flood E, Gajria K, Sikirica V, et al. The Caregiver Perspective on Paediatric ADHD (CAPPA) survey: understanding sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, treatment use and impact of ADHD in Europe. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:222–234. | ||

DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale IV for Children and Adolescents: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc; 1998. | ||

Zhang S, Faries DE, Vowles M, Michelson D. ADHD rating scale IV: psychometric properties from a multinational study as a clinician-administered instrument. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(4):186–201. | ||

Fridman M, Erder MH, Banaschewski T, Harpin V, Quintero J, Chen K. Factors associated with caregiver burden among treated patients in the caregiver perspective on pediatric ADHD (CAPPA) study in Europe. In press 2017. | ||

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2016. | ||

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. | ||

Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18(2):137–150. | ||

MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Erlbaum; 2008. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.