Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 14

Building Bridges for Indigenous Children’s Health: Community Needs Assessment Through Talking Circle Methodology

Authors Di Lallo S, Schoenberger K, Graham L, Drobot A, Arain MA

Received 6 August 2020

Accepted for publication 10 December 2020

Published 4 September 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 3687—3699

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S275731

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Marco Carotenuto

Sherri Di Lallo,1 Keren Schoenberger,2 Laura Graham,2 Ashley Drobot,2 Mubashir Aslam Arain3

1Stollery Awasisak Indigenous Health, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; 2Health Systems Evaluation and Evidence, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; 3Health Systems Evaluation and Evidence, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Correspondence: Mubashir Aslam Arain

Health Systems Evaluation and Evidence, Alberta Health Services, 10301 Southport Lane SW, Calgary, Alberta, T2W 1S7, Canada

Tel +1 403-943-0783

Fax +1 403-943-2875

Email [email protected]

Objective: The Stollery Children’s Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta, introduced the Stollery Awasisak team to provide targeted support to Indigenous families and their children. Talking Circles were conducted across northern communities from 2017 to 2019 to better understand how Indigenous people perceive the current state of healthcare services delivered by the Stollery Hospital.

Methods: The 2019 Talking Circles were held in six cities: Grande Prairie, Slave Lake, High Level, Fort McMurray, Edmonton, and Cold Lake, which were the biggest circles held to date with an attendance of 160 participants. Participants included members of Treaties 6 and 8, and Metis Nations of Alberta, as well as healthcare professionals in those regions.

Results: Talking Circles identified challenges Indigenous (First Nation, Inuit and Metis) pediatric patients and their families experienced from accessing care to transitioning home to exploring their positive experiences with the Stollery Hospital and other frontline collaborates. Through these circles guided by Elders in ceremonies, priorities and recommendations were made to help support pediatric patients and their families.

Conclusion: Multiple perspectives provided rich data on how best to adhere to the Truth Reconciliation of Canada 19th mandate and ensure equitable healthcare access to all Indigenous children. Together, leaders, healthcare providers, service providers and community members reflected on the lessons of the Medicine Wheel quadrants and the Seven Sacred Teachings, and brought forward four priorities; capacity building, continuity of care, culturally responsive care and increased communication.

Keywords: discharge planning, Indigenous Health, Talking Circles, cultural safety

Introduction

Indigenous History

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) released 94 “calls to action” that “redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation”.1 The TRC documents the impacts of colonialism and cultural genocide on Canadian Indigenous people, including the 120-year history of the Canadian Indian residential school system, which an estimated 150,000 children attended.1 The stories were told by survivors who recounted their traumatic experiences, its impact on future generations, and the resulting effect of distrust among Indigenous people toward government institutions. The consequences are seen in the health outcomes of Indigenous people who live in isolated communities, where there is a lack of available health services and on-going care management within the provincial-federal system.2,3

Stollery Awasisak Health Program

Notably, the 19th “call to action” is to address the healthcare inequalities for Indigenous (First Nation, Inuit and Metis) peoples.1 In Alberta, there are three large tribes: Algonquian (Blackfoot, Cree and Saulteaux), the Dene (Beaver, Chipewyan, Slavey and Sarcee), and the Siouan (Stoney) tribes.4 Despite the implementation of mandatory Indigenous awareness training for all Alberta Health Services (AHS) staff, systematic barriers continue to affect Indigenous families and children. Indigenous families living in rural and remote communities face the arduous challenge of finding reliable transportation to the nearest children’s hospital (eg 220–982 kilometers away). Transportation is usually obtained through a driver or a bus service. Moreover, local pharmacies are in short supply and the cost of living is high in northern communities. Also, many northern First Nation and Metis people considered Cree or Dene as their first language, yet few hospitals offered interpretation services in these languages. As a result, the Stollery Children’s Hospital introduced the Stollery Awasisak team to provide targeted support to Indigenous families and their children. Awasisak is named after the Cree word “children.” The Awasisak Health Program is comprised of Indigenous staff who provide programs and resources to support families and facilitate educational training for AHS staff. The group offers support for navigating health systems, and assistance with discharge plans (eg accessing mental healthcare), providing a safe space, daily tea and bannock, and Indigenous ceremonies (eg smudging and drumming). The Stollery Awasisak Health Program is guided by the Medicine Wheel principles,5 the Seven Sacred Teachings,6 and Jordan’s Principle.7–9

Project Scope

The Talking Circles were evaluated from 2017–2019 to maintain the standards of data quality and methods used (see Appendix A to review Guiding Evaluation Principles and Appendix B to review Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) Principles), and to better understand how Indigenous people perceive the current state of healthcare services delivered by the Stollery Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta. Talking Circles were held in urban cities in Northern Alberta, close to Indigenous communities, to allow all participants to travel shorter distances to a culturally safe space. The 2019 Talking Circles were held in Grande Prairie, Slave Lake, High Level, Fort McMurray, Edmonton, and Cold Lake (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 The map of six northern cities and participants’ home communities. |

Methods

Talking Circle Rationale

The Stollery Awasisak team, with Elders’ support, collected data through Talking Circles.10 Talking Circles allow participants to engage in a non-hierarchical dialogue where Indigenous people can feel safe to share stories, feelings, thoughts, and non-verbal gestures.11,12 For years, Indigenous people have used oral history and storytelling traditions to gather information, which facilitate community engagement and build relationships.11,13 To gain community trust, respect and support, each Talking Circle included at least one Elder and an Indigenous facilitator.10 Elders opened and closed with a prayer. Facilitators led participants in the dialogue by asking about their experiences at the Stollery Hospital, their visions for better Indigenous care, and priorities that can be related to leadership to help improve healthcare access or transition for Indigenous children.

Procedure and Protocols

Six Talking Circles were held from February to April 2019. Data were collected and stored according to the guidelines.14–16 Talking Circles ran between 10:00 am and 3:30 pm and broke for an hour lunch. The Stollery Awasisak team invited community members, Elders, healthcare providers (HCPs), and hospital leaders to a Talking Circle to discuss ideas on improving healthcare access for Indigenous children living in Central and Northern Alberta. Talking Circles were led by the Stollery Awasisak team who was also responsible for recruiting participants through letters, phone calls, and emails. Participants sat in a circle and passed a sacred object to indicate who speaks. A sacred item is typically a natural object, such as a rock, an animal figurine, or a feather. For the 2019 Talking Circles, a rock or a beaded turtle was used. The item was held, along with a microphone, then passed to the next person in a clockwise direction. Multiple recorders were placed throughout the room to capture stories from all sides of the room. Protocols asked participants to speak from the heart, tell their stories honestly and listen from the heart. Honorariums were given to Elders and family members to thank them for their reciprocity in sharing their stories. A member of the evaluation team also attended and was responsible for conducting real-time analysis during the story sharing. Notes were written on a flip chart visible to the participants of the Circle. Participants were invited to add to the flip chart at any point.

Participant Demographics

The 2019 Talking Circles were attended by 160 participants (18 to 40 people per session). Participants included healthcare leadership, community service providers, healthcare managers, HCPs, Indigenous community members, Indigenous leadership, social workers, and Stollery Hospital staff. Participants in the leadership roles, including zone and hospital directors and senior advisors, possess the power to enact systemic change. Community service providers included individuals from schools, Regional Collaborative Service Delivery (RCSD), Community Health Representatives (CHR), police, and other non-healthcare staff. Social workers were identified separately because of the particular emphasis on social work in Talking Circle discussions. Healthcare managers included case managers, coordinators, and health directors, among others. The HCP group was comprised of nurses, physicians, case workers, and other frontline staff. Indigenous community members primarily attended because of family hospital experiences, and encompassed Elders and Indigenous leadership. Finally, Stollery staff encompassed the Awasisak team themselves, as well as staff from Patient and Family-Centered Care.

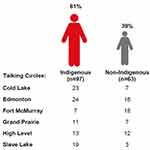

Most participants were of Indigenous descent (61%), while the others had non-Indigenous backgrounds (39%); (see Figure 2 for participant cultural backgrounds). The 2019 Talking Circle differed from past Talking Circles by including participants from various professional backgrounds and experiences (Figure 3), thus providing a richer spectrum of perspectives.

|

Figure 2 Participant cultural backgrounds. |

|

Figure 3 Participant professional experiences. |

For the purpose of displaying demographic information, participants’ roles were identified by their professional background (ie HCP); in contrast, quotes in this paper were identified by the perspective from which the participant was speaking (ie Indigenous community member), even when their professional role may be different.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted by the authors. The goal was to couple the holistic quality of storytelling from the Indigenous viewpoint with rigorous analysis informed by evaluation science.9 This combination is in accord with the Stollery Awasisak’s vision to achieve better healthcare by considering both knowledge frameworks in parallel. Thus, preliminary data was analyzed using a deductive approach based on knowledge from previous years of talking circles. New and repeated themes were identified and findings across the six talking circles were edited by all authors with frequent discussions to validate the accurate representation of participants’ experiences. Recordings were transcribed and participants’ identities were anonymized. Thematic and narrative analysis techniques were used to code transcripts in NVivo 12 by four evaluation team members who discussed coding structure throughout the analysis process.

The Stollery Children’s Hospital Awasisak Health Program is based on a holistic care model that incorporates the teachings of the Medicine Wheel, implementing the Seven Sacred Teachings alongside AHS Values and Strategies. The Seven Sacred Teachings are popular among all Indigenous people and must be practiced harmoniously with one another. Findings from the 2019 Talking Circles were reported based on the Indigenous Medicine Wheel framework and its implications were interpreted using the Seven Sacred Teachings to support the balance of walking in the Indigenous world view and the Western world view. Information was presented in three ways: context, priorities, and visions. The context is provided at the outset of the results section and provides an overview of systematic barriers to healthcare that routinely emerged in Talking Circles. The remainder of the results section is organized by Priorities, which are actionable recommendations made directly, or alluded to, by participants. To be a priority, an action item must be feasibly initiated, completed, or supported by the Stollery Awasisak team. Quotes are used to demonstrate the context from which these priorities emerge, including the different regions and perspectives they are associated with. The priorities make up the majority of the results and are organized by the four sections of the medicine wheel (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 The results organized by the four sections of the medicine wheel. |

Each priority is also accompanied by one or more Vision, which reflects “bigger picture” ideas about the future of healthcare, with emphasis on overcoming widespread systematic barriers to healthcare for Indigenous people. Visions are categorized by the Seven Sacred Teachings:

TRUTH – The turtle teaches to acknowledge that racism and prejudice still exist within healthcare.

WISDOM – The beaver teaches to raise awareness of leadership to help Indigenous people.

LOVE – The eagle teaches to invest in children by providing more services and resources.

RESPECT – The buffalo teaches to advocate for holistic care and hostility free environments.

HUMILITY – The wolf teaches to promote Indigenous awareness training to avoid misconceptions.

HONESTY – The sabe teaches to participate in Talking Circles to increase communication.

COURAGE – The bear teaches to build trust by encouraging collaboration and addressing trauma.

Results

The results section is presented first with the context of discrimination in healthcare, which emerged repeatedly during Talking Circles, accompanied by a vision. The remainder of the results section consists of four priorities, each of which are supported by visions.

Context: Discrimination in Healthcare

The Stollery Awasisak team understood that many Indigenous people felt distrust toward government institutions (eg hospitals) and government workers (eg social workers). This fear was echoed by many families across communities and stemmed from the historical consequences of colonialism and racism. Differences in western and Indigenous lifestyles had led some non-Indigenous HCPs to demonstrate assumptions held about Indigenous people. These misconceptions impacted Indigenous people’s healthcare experiences and discouraged Indigenous people from accessing proper care when needed.

“I’m scared to take my kids when they’re sick into the hospital. So we’re very afraid to talk to any other professionals to tell them any problems we’re having, whether it be health-wise, maybe food-wise, maybe addictions-wise, we keep it to ourselves because … the fear is, well, [social workers] are gonna take your kids. That’s my biggest fear and it shouldn’t be there, we shouldn’t have fear to use services meant for us.” – Indigenous community member, Grande Prairie

“Settlement children’s services [… is run by] white people that have no idea how we live on reserve. So if they come into a child’s home and there’s 6 children in a 3 bedroom [house] – ‘oh my God, this child can’t stay here, like he’s got to sleep with somebody.’ You know, like, they have all these misconceptions, and they don’t understand how we work, so they decide, well, in the best interest of the child we’re gonna remove them.” - Social worker, Grande Prairie

Priority 1: Capacity Building

North on the medicine wheel is indicated by the color white and symbolizes wisdom. In this paper, wisdom entails capacity building via education supported by leadership, outreach agencies, and training programs. It also involves expanding the Awasisak program based on suggestions brought forward in all Talking Circles. Wisdom reminds us of the importance of involvement from leadership and their role in raising awareness of Indigenous peoples’ social and financial needs in accessing healthcare.

Build capacity by expanding the Awasisak model: Many community members who had accessed Stollery Hospital services reported care had improved in recent years and this was largely due to the presence and assistance of the Stollery Awasisak team. Participants voiced the need for more cultural supports for patients and families at the Stollery Hospital, including recruiting Indigenous HCPs at hospitals. Moreover, participants felt it would be helpful if local hospitals had an outreach worker to contact the Awasisak teams beforehand so the team knew when to expect families at the Stollery Hospital. Others suggested creating videos in different Indigenous languages to help new patients understand hospital processes. Finally, adding a psychologist, counsellor or Elder to the Awasisak team would help families going through difficult times. These suggestions can help the Stollery Awasisak team build capacity toward helping more patients and families.

“I would love to see the [Stollery Awasisak] model in all cities that have […] Indigenous communities coming to them. […] That is something I would love to see go to Alberta Health Services leadership. […] Your model is fantastic. I think […] if we had a model like that when […] one of my children [was] admitted at the hospital then I’[d have] somebody who [was] going to communicate with us and tell us what is going on. [This way] we can support the student and the family better when they’re released or when they’re not released, […] help them academically […] so that they can still graduate on time and not have academic gaps […].” – Indigenous community member, Fort McMurray

Build capacity by encouraging leadership involvement: Participants noted that high turnover and lack of involvement in chief councils had communities feeling frustrated and neglected by their leaders. Community members urged leaders to become involved and to advocate on their behalf. Additionally, Metis people were not included in many of the resources available to First Nations people and they required information about additional supports. Community members were also seeking help to navigate bureaucratic processes and documents, such as the medicine chest clause, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Health Canada policies, Jordan’s Principle, Treaty and Status rights, and healthcare jurisdictional boundaries. Participants stated specifically that the separation of federal (on reserve) and provincial (off reserve) jurisdiction was not always clear and that improvement is needed in the coordination between federal and provincial bodies. Improved understanding of governance structures can build capacity among Indigenous people and help them to advocate for themselves.

“AHS has a responsibility as a government body to commit to TRC calls to action because that’s all we have to date […]. The government promised to provide adequate healthcare [and] … to make [it] a priority. We [also] have a medicine chest clause. The government of Canada and province of Alberta is responsible for providing funding […] for the health needs of the Indigenous people. If we need transportation from Fox Lake to Edmonton, if we need better healthcare centers in our own communities, they’re the ones that are responsible and they should be held accountable I think that should be the priority and that’s where we should start if we’re going to think system on this grass root’s level, all I can say is prioritize the need for respect.” – HCP, Edmonton

“In our community …, we are governed by federal. The minute we leave the reserve, we become provincial. So we always get torn in between those two governments. So that’s the information that we want to get as well, is where does the federal come in? Where does the provincial come in?” – Healthcare manager, High Level

“Most of the time these policies are done by people and teams and boards who never actually spent any time in the communities and feel free to dictate how things should run. And with no consideration to how things actually run and recognizing that every community even in the same region, the same vicinity, the same municipality run differently and there’s no respect or regard to that.” – Indigenous community member, Fort McMurray

Vision of Wisdom

In the Seven Sacred Teachings, the beaver teaches us the value of making informed decisions through wisdom. Leadership can follow this teaching by advocating for funding and to increase exposure for outreach programs such as the Stollery Awasisak program. Many HCPs noted the benefits of expanding the Stollery Awasisak by increasing resources and services, such as having a counsellor and an outreach coordinator at local hospitals. To accomplish this, however, community members stated the need to include more leadership in community events. Community members and HCPs noted the lack of leadership involvement has led to confusion when navigating the bureaucratic systems. Thus, Indigenous people proposed that leadership attend Talking Circles in remote communities to hear people’s stories and learn more about their daily struggles when accessing healthcare. This, in turn, will communicate information to the community and help leaders advocate for the needs of community members. Building capacity in leaders makes it possible to pass down wisdom to the community.

Priority 2: Continuity of Care

West on the medicine wheel depicts understanding of resources and is represented in red on the medicine wheel. This paper explores the understanding of resources available in the context of continuity of care, which refers to the services and resources needed in northern communities. Communicating available supports and improving existing supports can assist children in their care before, during, and after hospitalization. Increased understanding of resources also speaks to the principle of love.

Promote continuity of care by bringing more staff to northern health clinics: Past Talking Circle participants reported a need for more resources and services at local hospitals. Specifically, they mentioned the need for more specialized HCPs to assist with discharge and transitions from pediatrics to adult wards. It was noted that rehabilitation professionals such as Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational Therapists, Physical Therapists and Psychologists were in high demand. To recruit these professionals, they recommended focusing on the attraction and retention of HCPs in northern communities. This need has been addressed by introducing Teddy Bear Fairs to communities, where multi-disciplinary rehabilitation teams attend annually to screen children’s speech, language and motors skills, both fine and gross. Parents receive recommendations on how to assist children in achieving milestone goals. Community members requested more Teddy Bear Fairs joined by the Awasisak Team, as well as HCPs working with Jordan’s Principle to help the community become aware of available programs. Continuity of care can, therefore, be prioritized by providing more services from specialized HCPs in northern communities.

“Let’s do it a one-stop shop, see the pediatrician, go over to the next room, see the telehealth, see the team on the other side. Maybe there’s going to be social worker, maybe there’s gonna be [occupational therapist or physical therapist] referrals, and try to get through, instead of making these people go to all these different departments, let’s do a one-stop shop, like Teddy Bear Fairs, let’s get them what they need for their child, and then move on.” – Healthcare manager, Cold Lake

Promote continuity of care by improving services before and after Stollery Hospital care: Participants made suggestions that could help families who are required to travel long distances to the Stollery Hospital for their child’s care. Before traveling, participants noted, it would be helpful to receive information about the hospital and surgery, and a video in different Indigenous languages. Participants also recommended that a transition house for long-term patients could help with accommodation costs. Participants felt that, following discharge, it would be helpful to receive more information about resources and services available to them in their local communities for follow-up care. Finally, whenever possible, HCPs recommend using telehealth or traveling multi-disciplinary teams to perform assessments locally because it is more cost-effective for families and makes children feel more at ease.

Vision of Love

The Seven Sacred Teachings features the eagle, which teaches that love is unconditional and its foundation is understanding. Continuity of care can be improved through HCP staff that live and participate in local community events. Improving recruitment and retention should include the encouragement of Indigenous youth to study healthcare fields for use in the community. Community members want the best for their children and are dedicated to improving the conditions of children’s care. Ultimately, the lesson of love requires promoting continuity of care by understanding the resources provided by specialized HCPs and improving services before and after Stollery Hospital care.

Priority 3: Culturally Responsive Care

On the medicine wheel, yellow represents east and, in this paper, refers to awareness of others’ needs. The Talking Circles suggested the need for culturally responsive care in hospitals, and the acknowledgement of Indigenous people’s lifestyles and history. This requires respect for the Indigenous way of living and reflecting it in government programs. Additionally, it requires humility when acknowledging the struggles that result from colonialism and when adapting care to better meet Indigenous patients’ needs.

Raise culturally responsive care awareness by addressing specific Indigenous needs: The Stollery Awasisak team was instrumental in providing resources to families. For example, they helped families navigate the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) Medical and Transportation Program, which covered daily costs for one parent’s travel when their child was in care. The Awasisak program helped parents by advocating on their behalf to acquire funding. This was extremely helpful to Indigenous families who struggled to pay for accommodation, transportation, childcare, and meals while their child was in the hospital. Due to the nature of the collective family unit, Indigenous families relied heavily on having support from the entire family. The Awasisak team had also introduced families to affordable accommodation at the Ronald McDonald House, which offered free shuttles to the Stollery Hospital and back. This was helpful for Metis families who did not receive any support through the NIHB Medical and Transportation Program. The Awasisak team also provided a safe space for Indigenous people to perform smudging and prayer, and provided Indigenous representation in the hospital. Families reported feeling safer and had increased trust in the healthcare system when the Awasisak team was involved. Understanding specific cultural needs facilitate culturally responsive care for all Indigenous people.

“I think that if we can expand programs such as Awasisak program and saying it’s expanding based on relationship, based on collaboration, based on holistic care where we can potentially transcend to home communities, build that trust, build those relationships. Then bring in those providers to home communities so the families don’t have to break-up and travel into these big urban centers that are really scary, really overwhelming, and really they’re just hard amongst all of those other barriers.” – Healthcare manager, Edmonton

Raise culturally responsive care awareness by teaching Indigenous culture and fostering hostility-free environments: A goal of the Stollery Awasisak team is to educate and raise awareness about Indigenous needs with non-Indigenous leadership and HCPs. The history of colonialism is taught using the blanket exercise. They also emphasize that holistic frameworks are integral to Indigenous health. AHS has introduced mandatory cultural sensitivity classes to teach employees about Indigenous history, lifestyles, and generational trauma. The long-term goal is to integrate these lessons into practice. However, AHS can take further steps to provide education.

A concern that emerged in Talking Circles was that foreign doctors and HCPs were less knowledgeable in Indigenous history. It was suggested special training be provided to immigrating doctors and students in medical programs. This could include a trip to northern rural communities to understand the Indigenous lifestyle and their specific needs.

In general, the theme of racism and its impact on experiences with healthcare pervaded discussions at all Talking Circles. An idea was introduced through the 2019 Talking Circle, where the concept of hostility-free environments could be used to address racism directly. Hostility experienced in the healthcare system includes the stigma experienced by community members who attend urban universities for education, but are greeted with distrust upon returning to their communities. Participants recommended AHS promote core principles that help establish a hostility-free environment.

“But I think this – what we’re doing here – is getting education to everybody out there. Trying to address the stigma associated with Indigenous peoples, on racism, financial stability, and addiction. Culturally competent care is really important, and culturally safe care is actually the really critical piece.” - HCP, Grande Prairie

“AHS really needs to step up their game and try to create these non-hostile environments where staff feel safe and the families feel safe. They’re able to voice their opinion without feeling ashamed and just feeling uncomfortable talking to a social worker or talking to a bedside nurse, not feeling like they’re being watched over, analyzed so that’s one huge thing that I hope AHS will begin to look at.” - HCP, Edmonton

Vision of Respect

According to the Seven Sacred Teachings, the buffalo guides us in building respect, which is demonstrated by honoring each other’s personal customs. Culturally responsive care involves understanding the Indigenous needs by becoming aware of their culture and traditions, and by supporting Indigenous representation in healthcare. Indigenous people feel safer when they feel represented. When non-Indigenous HCPs participate in community events, such as sweats and smudging, they build trust and solidify relationships with community members. Moreover, the Stollery Awasisak team makes Indigenous communities feel respected. A future for healthcare built on mutual respect would require non-Indigenous HCPs to learn about Indigenous needs and culture, and build relationships with Indigenous people, thus awareness can improve care for all patients.

Vision of Humility

The wolf instructs us in humility, reminding us to be humble while learning from others. Culturally responsive care can be facilitated by integrating Indigenous values into western practice. This is supported by the AHS mandate to provide staff with Indigenous cultural awareness training. Awareness needs to be continuously put into action. For example, the idea of hostility-free environments could help Indigenous patients and HCPs feel safer, and reduce stigma against Indigenous people. Moreover, providing action-based education to all incoming HCPs can improve the health system. These changes would adhere to TRC mandates for equal access to healthcare for all people. To achieve any of these, leadership and practitioners must be humble and aware enough to acknowledge and address existing barriers to culturally sensitive care.

Priority 4: Increased Communication

The south section of the medicine wheel is for knowledge of one another, and is depicted by the color blue. Improved knowledge can be achieved through better communication between HCPs and Indigenous patients. This requires speaking honestly and listening actively at Talking Circles to understand the issues faced by Indigenous people. It also requires courage to face the trauma experienced and to work together to find solutions to overcome barriers.

Increase knowledge of the language and cultural barriers affecting Indigenous people: As stated earlier, few hospitals offered interpretation services in Cree or Dene languages for northern First Nation and Metis people. One of the Stollery Awasisak team members speaks Cree. The team had discussed the value of also adding a Dene speaker. Culturally, Indigenous people were identified as shy and hesitant to express their needs, especially to non-Indigenous HCPs using medical jargon. Indigenous people relied heavily on Indigenous community members and HCP champions who advocated on their behalf. These champions recommended increasing awareness of outreach programs in community members and sharing stories in Talking Circles. These activities would demonstrate to people how to advocate for themselves. They suggested outreach programs, like the Stollery Awasisak team, could advertise in community newspapers, Facebook groups, health display boards, and Teddy Bear Fairs. By increasing communication, people will be equipped to find others who can support them and advocate for them in both the western and Indigenous worlds.

“Our Native people, we’re shy, we don’t talk. And this is where our barrier is with our home people. The barrier is that they do not advocate for themselves, they do not speak for themselves. It’s important to help them to understand, speaking not in medical language, but in plain language so everybody understands and participates in decision making.” – Community service provider, Cold Lake

“These talks are really good. I think you know truth ultimately comes out when Talking Circles happen. Much vital needed truth so thank you for sharing those and with sharing that truth it rips that culture of fear away around some issues which then only brings us and drives us forward so I am very grateful for that.” - AHS leadership, Slave Lake

Increase knowledge through community and local hospital collaboration to ensure equal healthcare access for all people: Collaboration between hospitals and communities had already taken shape in some areas as HCPs were increasingly adopting culturally appropriate policies. Families stated their approval of the holistic care techniques demonstrated by the staff at the Stollery Hospital. The communication breakdown seemed to occur between the Stollery Hospital and the local hospitals during discharge. Community members and HCPs suggested that the Stollery Awasisak team continue to network and build connections to better assist Indigenous patients traveling to and from the Stollery Hospital. The lack of communication can affect medication supply and needed services for Indigenous children. The challenge, however, was that local healthcare facilities experienced high staff turnover. This made building trust between clinicians and families difficult and added strain on the efficiency of care. Increasing collaboration between key groups requires addressing Indigenous patients’ fears within the healthcare system and taking steps to understand both the western and Indigenous viewpoints and how they affect healthcare.

“Make sure our children are being served in an equitable way. That means that every child in Alberta deserves to have equal access to healthcare and services no matter where they live in this province and I know that there are some barriers. We may not be able to fix them all, but we sure can break a lot of them down and it could even be just communicating with each other, working with Alberta Health Services.” – Community service provider, Slave Lake

Vision of Honesty

According to the Seven Sacred Teachings, the sabe teaches the lesson of honesty. Honesty entails speaking up about personal experiences. This is a challenge for Indigenous people who tend to have quieter voices or because English is not their first language. Their silence has been further intensified as a result of historical atrocities and the false beliefs about Indigenous people held by some non-Indigenous HCPs. Talking Circles provide a safe place for families, community members, and Indigenous HCPs to share their knowledge through visions for a better tomorrow. Moreover, Talking Circles provide a good platform to network and build connections with outreach programs and services. The lesson of honesty highlights the importance of having a voice and advocating for oneself. In turn, this helps non-Indigenous HCPs better understand Indigenous people and their needs.

Vision of Courage

Finally, the bear teaches us about the power of courage. Communicating knowledge between communities and healthcare facilities is an important element for overcoming fear and for facing trauma. Local hospitals can show courage by reaching out to connect and collaborate with communities and outreach programs. By reaching out to communities, health institutions can help rebuild trust and ensure all children receive seamless and equitable access to healthcare. Outreach information can be promoted through advertisements in local community Facebook pages and newsletters to help reach more community members. Finally, Talking Circles provide a platform for networking and building connections where community service providers, AHS leadership, healthcare managers and HCPs, Indigenous leaders and community members can meet to share knowledge and brainstorm ideas. The courage to speak up and challenge persisting issues is key to improving communication and improving access to healthcare services.

Discussion, Conclusion and Recommendations

Indigenous neonatal and pediatric family stories provide impactful voices on solutions for health care equity and access of services to the Stollery Children’s Hospital, Awasisak Indigenous Health Department. The findings have been used to hire more Indigenous staff to the Awasisak team to improve discharge planning, create a culturally safe space for families, became a department within the Stollery Children’s Hospital, expanded communication strategies with communities for successful discharge planning, provide opportunities for culturally responsive care training and experiential learning in nursing orientation and the blanket exercise, and collect and investigate research and evaluation findings. Other studies have shown that hiring staff with indigenous background or someone whose values and motivations for working with Indigenous populations is highly important in reducing barriers in healthcare access.17 It sometimes challenging to recruit staff with indigenous background due to the shortage of indigenous staff in healthcare.18 However, provision of cultural sensitivity training to staff in healthcare helps achieving cultural competence in the organization.19,20 Alberta Health Services implemented a mandatory Indigenous cultural competency training for all staff to increase cultural competence and the provision of culturally sensitive care to patients.

The Awasisak Department has implemented outreach services by hiring a Registered Nurse Case Manager for the hospitals in Edmonton area. Also, to expand outreach services to rural and remote communities, the department is exploring oppportunities to hire outreach pediatric navigator, travel teams and outpatient clinics. Other research in Alberta also reported that a community-based providers to support patient and families navigating the available services is crucial for a program to be effective.21 Appropriate and sufficient workforce is central to the delivery of services which is acceptable and accessible to the community.22 Lastly, the findings from the program evaluation explored strategies to expand the Awasisak model of care to other children’s hospitals across Canada.

In summary, the 2019 Talking Circles were the biggest circles held to date with an attendance of 160 participants. Participants included Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, such as community service providers and social workers, healthcare managers and HCPs, AHS leadership, Stollery Hospital staff members, Elders, Indigenous leadership, and Indigenous community members. The Stollery Awasisak team facilitated discussions to uncover people’s experiences in healthcare and their future visions for healthcare, and suggested next step priorities to improve healthcare access. Multiple perspectives provided rich data on how best to adhere to the TRC 19th mandate and ensure equitable healthcare access to all Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Together, leaders, HCPs, service providers and community members reflected on the lessons of the Medicine Wheel quadrants and the Seven Sacred Teachings, and brought forward eight recommendations to consider:

Priority 1: Capacity Building

- Expand the Awasisak model across Alberta

- Encourage more leadership involvement

Priority 2: Continuity of Care

- Recruit more HCP staff to northern health clinics

- Improve services before and after Stollery Hospital care

Priority 3: Culturally Responsive Care

- Raise awareness of Indigenous culture and their lifestyle needs

- Address judgement and foster hostility-free environments

Priority 4: Increased Communication

- Learn about the language and cultural barriers affecting Indigenous people

- Collaborate with communities and local hospitals to ensure equitable healthcare access

These priorities can help clinical practices make the needed changes to decolonize healthcare by integrating the Indigenous medicine wheel paradigm to the western medical framework. Walking parallel in both worlds requires hearing the truth through Talking Circles and healing the trauma through wisdom, understanding, awareness, and knowledge.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was considered as a Quality Improvement project and the need for approval was waived based on the Alberta Research Ethics Community Consensus Initiative (ARECCI) tool. All data collection, management and storing procedures complied with the Health Information Act and the Freedom of Information and Privacy Act in addition to the First Nations Principles of OCAP®. Written informed consent was received from each participant and the responses were anonymized for publication.

Acknowledgments

The Talking Circles initiative was completed by the Stollery Children’s Hospital Awasisak Indigenous Health Program, and the results were compiled and analyzed by Health Systems Evaluation & Evidence. This report will guide how the Awasisak Indigenous Health Program endeavors to improve and enhance Indigenous patient family experiences.

We would like to acknowledge the 160 Talking Circle participants for their time and effort; without their stories and willingness to share their experiences, their ideas and recommendations would not be available to direct the Awasisak Indigenous Health Program.

We would also like to thank the following people for their generous contributions of time, expertise and experience:

- Stollery Awasisak Team: Audrey Thomas, Hailea Purcell, Chrystal Plante, and Pauline Cardinal

- Health Systems Evaluation and Evidence Project Assistants: Delane Linkiewich, Rabia Wattoo and Tristan Pidner

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Alberta Health.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Truth and Reconciliation Commision of Canada. Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: calls to action; 2015. Available from: http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf.

2. Fridkin AJ. Addressing health inequities through Indigenous involvement in health-policy discourses. Can J Nurs Res Arch. 2012;44(2):108–122.

3. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Fourth national forum on indigenous determinants of health: “Nakistowinan (Stop In) - Pimicisok (Stock Up) - Kapesik (Stay Over)” - Proceedings Report. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2019.

4. Alberta Aboriginal Relations. Aboriginal Relations annual report [2012–2015]; 2015. Available from: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2291-708x.

5. Laframboise S, Sherbina K. The medicine wheel; 2008. Available from: http://www.dancingtoeaglespiritsociety.org/medwheel.php.

6. Alberta Regional Professional Development. Seven sacred teachings; 2019. Available from: http://empoweringthespirit.ca/cultures-of-belonging/seven-grandfathers-teachings/.

7. Government of Canada. Jordan’s Principles; 2019. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/jordans-principle.html.

8. Johnson S. Jordan’s principle and Indigenous children with disabilities in Canada: jurisdiction, advocacy, and research. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2015;14(3–4):233–244. doi:10.1080/1536710X.2015.1068260

9. Blackstock C. Toward the full and proper implementation of Jordan’s principle: an elusive goal to date. Paediatr Child Health. 2016;21(5):245–246. doi:10.1093/pch/21.5.245

10. Di Lallo S, Schoenberger K, Graham L, Arain MA, Drobot A. Collaboration to Action: A Children’s Health Case Study in Knowledge Co-Creation, Indigenous Peoples and Talking Circles. Alberta Health Services; 2019.

11. Lavellee L. Practical application of an indigenous research framework and two qualitative indigenous research methods: sharing circles and anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int Inst Qual Method. 2009;8:10. doi:10.1177/160940690900800103

12. Rupert R. Returning to the Teachings: Exploring Aboriginal Justice. Penguin Books; 1996.

13. Kovach M. Conversational method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child Family Rev. 2010;14(1):123–136.

14. Province of Alberta. Health Information Act; 2018. Available from: https://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/H05.pdf.

15. Province of Alberta. Alberta Evidence Act; 2019. Available from: http://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/A18.pdf.

16. Province of Alberta. Freedom of information and protection of privacy; 2019. Available from: http://www.qp.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=F25.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779762071.

17. Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):544. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1707-9

18. Nguyen NH, Subhan FB, Williams K, Chan CB. Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in indigenous communities of Canada: a narrative review. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):112. doi:10.3390/healthcare8020112

19. McConkey S. Indigenous access barriers to health care services in London, Ontario. The engaging for change improving health services for indigenous peoples qualitative study. Univ West Ont Med J. 2017;86(2):6–9. doi:10.5206/uwomj.v86i2.1407

20. Brooks-Cleator L, Phillips B, Giles A. Culturally safe health initiatives for indigenous peoples in canada: a scoping review. Can J Nurs Res. 2018;50(4):202–213. doi:10.1177/0844562118770334

21. Loyola-Sanchez A, Pelaez-Ballestas I, Crowshoe L, et al. “There are still a lot of things that I need”: a qualitative study exploring opportunities to improve the health services of first nations people with arthritis seen at an on-reserve outreach rheumatology clinic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1076. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05909-9

22. Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health. 2018;14(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.