Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 12

Bipolar disorder and adherence: implications of manic subjective experience on treatment disruption

Authors Bulteau S, Grall-Bronnec M, Bars PY, Laforgue EJ , Etcheverrigaray F, Loirat JC, Victorri-Vigneau C, Vanelle JM, Sauvaget A

Received 16 September 2017

Accepted for publication 10 November 2017

Published 27 July 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 1355—1361

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S151838

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Samuel Bulteau,1,2 Marie Grall-Bronnec,1,2 Pierre-Yves Bars,3 Edouard-Jules Laforgue,1 François Etcheverrigaray,4 Jean-Christophe Loirat,3 Caroline Victorri-Vigneau,2,4 Jean-Marie Vanelle,1 Anne Sauvaget1

1CHU de Nantes, Addictology and Liaison Psychiatry Department, Nantes, France; 2University of Nantes-University of Tours, INSERM, SPHERE U1246 – “methodS for Patients-centered outcomes & HEalth REsearch”, l’Institut de recherche en Santé 2, Nantes, France; 3Clinique du Parc, Nantes, France; 4CHU de Nantes, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Nantes, France

Objective: Therapeutic observance is one of the cornerstones of bipolar disease prognosis. Nostalgia of previous manic phase has been described as a cause of treatment retrieval in bipolar disorder. But to date no systematic study has examined manic episode remembering stories. Our aim was to describe manic experience from the patient’s point of view and its consequences on subjective relation to care and treatment adherence.

Patients and methods: Twelve euthymic patients with bipolar I disorder were interviewed about their former manic episodes and data was analyzed, thanks to a grounded theory method.

Results: Nostalgia was an anecdotal reason for treatment retrieval in bipolar I disease. Although the manic experience was described as pleasant in a certain way, its consequences hugely tarnish the memory of it afterward. Treatment interruption appears to be mostly involuntary and state-dependent, when a euphoric subject loses insight and does not see any more benefit in having treatment.

Conclusion: Consciousness destructuring associated with mood elation should explain treatment disruption in bipolar I patients more than nostalgia. Taking a manic episode story into account may help patients, family, and practitioners to achieve better compliance by improving their comprehension and integration of this unusual experience.

Keywords: nostalgia, mania, compliance, insight, psychoeducation

Introduction

Up to 4.3% of primary care patients suffer from bipolar disorder.1 The prevalence of inobservance in bipolar disorder is common (up to 60%) and known to be the main reason for relapse and rehospitalization as well as a key prognostic factor at 15 years.2 Psychosocial intervention and information about medications can obviously improve compliance,3 but inobservance remains a complex phenomenon. The main objectively identified risk factors for non-adherence are forgetting to take medications, substance use disorders, personality disorder, poor social and affective support, side effects, poor information and poor understanding of the condition, concerns regarding having to take long-term medications, the number of manic episodes, and depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms.4–8 Subjectively, inobservance may not only be related to denial as we could initially think, but some other reasons are also highlighted by patients themselves: artificial mood control, manic nostalgia, depressive feelings, and taking medications acting as reminders of the disease.9 Thus, a subjective gap could exist between practitioners and patients,10,11 which is crucial because of the importance of the physician–patient relationship in achieving medication compliance. Insight is a central dimension considering observance question. It involves complex processes such as judgment, verbal consciousness, and recognition.12 Insight impairment in bipolar disorder is not a trait as it is in schizophrenic disorder but is linked to the severity of manic symptoms.13 Most of the bipolar patients are aware of their mental disorder, as recently shown using the Scale to Assess Unawareness of mental Disorder (SUMD) in 33 bipolar individuals. Interestingly, SUMD scores were mostly associated with Young Mania Rating Scale scores, assessing manic symptoms, but not with other neurocognitive variables.14 As we said, manic nostalgia has conventionally been mentioned as a frequent reason for treatment withdrawal. Thus, subjective manic experience and what the patient remembers from that period should be crucial for treatment continuation. However, more quantitative and qualitative data collection is needed to examine the impact of manic symptoms on observance and follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, only one qualitative study has been conducted on the subjective relationship to one’s own bipolar disease and it concerned the potential positive consequences of the disorder.15 There have been no previous publications based on systematic qualitative analyses of manic episode stories. The objective of this study was to analyze spontaneous manic phase stories in a sample of bipolar I patients. The second aim was to identify common characteristics of that experience between subjects providing adequate discussion about treatment compliance.

Methods

Recruitment

All the patients included in the study were adults with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (BDI). The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 2) age between 18 and 60 years; 3) willingness to give written informed consent; and 4) a remission period of more than 3 months since the last manic episode. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) bipolar disorder secondary to an organic cause; 2) current mood episode (mania, hypomania, mixed state, or major depression) confirmed by DSM-IV diagnosis and Montgomery and Äsberg Depression Scale score (MADRS) <15 and Young Mania Rating Scale score <6; 3) age >60 years old; 4) current substance use disorder; and 5) intellectual deficiency, cognitive impairment, language difficulties. This study was performed from February 2013 to September 2013 in the Psychiatry Department of the Nantes University Hospital. No change in our current clinical practice and no randomization were performed. As it was an observational epidemiologic study, according to the French legislation (articles L1121-1 paragraph 1 and R1121-2, Public health code), approval of the ethics committee was not needed to use data. In February 2013, a large number of psychiatrists from Nantes University Hospital and one from a clinic were asked by e-mail to provide a list of bipolar I patients. Twelve patients were identified. The investigators offered a telephone interview to each of them and all of them agreed to participate in the study and provided written consent.

Procedure

The researcher used a semistructured interview guide to conduct in-depth interviews with each patient at their usual consulting room at Nantes University Hospital. All the interviews were conducted in French (native language of the patients) and audiotaped, transcribed, anonymized and analyzed by the authors. The manuscript was later translated by ADT International (a professional translation agency). Each interview was in three parts:

- The patient was asked to give a free and spontaneous story of the manic episode (if only one) or of the most significant (if several).

- Seven systematic dimensions were explored through the following questions: insight into the pathological nature of the episode, its impact, relationship to mania, knowledge of the disease, relationship to health care, treatment compliance, and the subject’s ability to self-assess his mood.

- Do you consider that symptoms occurring during these periods were a problem for you?

- Since then, what impact has that experience had on your daily life?

- Do you often remember these periods? If so, how do you feel about them?

- In your opinion, what can explain these disorders? What do you know about the disease?

- What do you think of the treatment you received during your hospitalization, and afterward?

- Do you think that medication could be useful to treat or prevent symptoms? Do you sometimes take your treatment differently than how it is prescribed or are tempted to stop it? If so, why?

- Is it generally difficult for you to judge your mood?

- Several standard evaluations were performed:

- World Health Organization Quality of Life self-questionnaire (WHO-QoL-26),

- MADRS,

- Young Mania Rating Scale.

Analysis

The analysis was inductive, using a grounded theory approach,16,17 allowing themes to emerge only if there was data in the transcript to support the presence of the theme and not seeking to support or disconfirm existing proposed hypotheses. Grounded theory methodology involves putting themes that emerge from the data into a structured model. We included all the major themes elicited until saturation. All the transcripts were read, coded, and discussed by the research team. The data were coded and categorized according to continuing analysis. The transcripts were reread with these themes in mind and recoded, taking particular note of data that was not captured by the themes. Further discussion led to refining and relabeling of the key themes.

Results

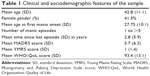

Table 1 shows the clinical and sociodemographic features of the sample. The sample was large in terms of age, time between mania and interview, and number of episodes leading to representative variability in the presentation of several illnesses. In the quality of life assessment, the four dimensions that obtained the poorest scores were “need for daily medication”, “sexuality”, “ability to work”, or to “concentrate adequately”. The mean age was 42.8 with a maximum of 54 years.

Thematic analysis

Manic experience inferred from spontaneous narration

All the patients readily agreed to share their experience and could remember their episode quite accurately, sometimes several years later. Their recounting of these memories was prompt and vibrant, with almost visual scene descriptions and a great deal of detail or digression. The more the narration developed, the more the memories were vague, sometimes with a few gaps, or the impression of being a spectator to one’s own agitation or acting automatically.

Initial context

Just before the start of the episode, the patients described either existential stress (7/12) like a “departure”, “death”, “burn-out,” or “a new job” or an especially favorable time (5/12).

Spontaneous evolution

At the beginning, the subjects noticed a liberating experience with a feeling of well-being (9/12) (“I was so well”, “more than pleasant”, “enthusiastic”) and a feeling of freedom (6/12) (“we had the impression of being finally alive, without any hindrance”). A sense of one’s own excellence developed with the observation of unusual energy and hyperactivity (11/12) (“very excited”, “I had little sleep”, “200 miles/h”); loads of ideas, impression of creativity (9/12) (“lots of projects”, “fascination: how far can we go?”, “huge creativity”); great self-confidence and the feeling of being all-powerful (8/12) (“everything is possible and nothing scares you”, “being yourself, only better”, “clearly above everyone”); risk-taking with the intuition of being out of danger (7/12) (“blessed by the gods, protected”, “no awareness of danger”, “nothing would happen to me”); hypersociability (7/12) (“easy communication, humor”, “I constantly met many people”, “loud-mouthed, braggart, pleasant company”); and high intelligence (5/12) (“hyperconnection, intellectual hypersensitivity, fluidity”, “very clever […] supra-consciousness”, “more intelligent than other people”). The patients also described a kind of exhaustion characterized by a loss of control (11/12) (“very unstable, difficult to contain”, “overflow”, “stronger than you”, “I’m not me”, “being aware that I can do anything but doing it as well”) and carelessness associated with excess and disinhibition (10/12) (“I care about nothing, I live my life”, “everything to excess”, “complete chaos, no limit, unnatural condition”). Lack of awareness was reported throughout: self-image distortion and lack of awareness of one’s own state (12/12) (“they found me agitated, arrogant, lunatic, frightening”, “they saw me change before I realized it”); partial consciousness (9/12) (we have some awareness of it, but we say to ourselves […]”, “denial of consequences”, “wishing that it would go on forever”); memory gap and contractions (7/12) (“I can’t remember everything”, “it’s vague”, “it seemed to me to be a very short period of time”); moral reflection (4/12) (“there was no feeling of guilt”, “to convince oneself that it’s not something bad, it’s strange”). The patients then noticed a feeling of unease like an oppression, an overflow (7/12) (“nervous, not calm”, “that goes in every direction, there is some stress”, “strange, some feeling of illness”, “overflow”).

“Stop” and start of hospitalization

The patients described intervention by relatives or reality constraints (5/12) (“my parents came to bring me in”, “stress that puts your feet back on the ground, no choice, there goes the energy”, “somewhat exhausted”, “no rebellion, it has gone far enough”). They sometimes called upon a third person (3/12) (“the neighbor across the road, to help”). On admission to hospital, anger was reported (6/12) (“very angry and nervous when I arrived”, “not easy to make me listen to reason […] like enemies”), associated with arguing (7/12) (“I tried to reduce the quantity of medication”, “couldn’t wait to be discharged”, “I took whatever they wanted so as to be discharged as soon as possible”).

Progressive mood normalization

As their exaltation died away, the patients experienced an underlying sense of appeasement (8/12) (“a crazy well-being, like rain when it is too hot”) and the staffs’ competence and kindness (8/12). They also noticed a feeling that they could relax in a safe environment (5/12) (“the right to ‘let go’”, “reassuring place”) and the importance of normal activities and family visits (5/12) (“at my husband’s visit, I cried”, “return to normal life”). Four of them reported amnesia during most of their hospitalization and three described a mood switch (“anxiety and guilt soon developed”, “a gray veil on my life”).

Results of directive interviews

Awareness of the pathological nature of the episode

After the episode, all the patients were conscious of its pathological nature (“outside reality”, “like me in some respects but not normal”).

Consequences of the episode

Most of them identified the negative impact of the episode, notably from the relationship standpoint (10/12) (“rebuild it entirely, severe professional and affective consequences”, “make relatives suffer”). Nine out of 12 insisted on the need for constant vigilance (“never going through that again”, “I’m suspicious of euphoria”). Seven subjects thought they remained vulnerable (“hypersensitivity, no shell”, “difficulty in committing, no longer felt self-control”), and many occurrences highlighted the importance of good life hygiene and ritualization (“I don’t let myself go without sleep”, “limit alcohol and take my pills”). Half of them described a consecutive depressive state (“empty battery, no desire”), and one-third emphasized outsider skills and self-care (“I listen to advice from my family circle”).

Relationship to the manic episode

Most of the patients had a critical attitude (9/12) (“benefits cancelled out by consequences”, “I put my safety at risk and don’t want to do that anymore”, “nothing constructive”). Memories were sparse in daily life (7/12) (“I prefer to look to the future”). The theme of self-preservation occurred six times (“I was lucky, I could have died”). This unique experience was minimized for half the patients (“that’s my temperament”, “I took the chance to experience that”). Five out of the 12 underlined the ephemeral and illusory nature of the experience (“Pleasure alone, but living without others, is not interesting”) and five reported regrets and resentment (“a bad disease that shattered my life”). Only one subject mentioned nostalgia (“I’d have liked to keep that optimism, that’s what I’m looking for: everything is soft, my dream in some way”).

Relationship to health care

Most of the patients had confidence in the staff, with a good doctor/patient relationship (10/12) (“satisfied”, “the follow-up restores me”). Four out of 12 stressed the importance of empirical learning (“after several phases my mind can understand it”, “I know I can evaluate it now”) and three highlighted the symbolic value of hospitalization.

Relationship to medication

The need for compliance was highlighted (9/12) (“I take my treatment every day, it makes me regular”, “the price to pay to avoid being dependent on emotions”, “the only way to stop this manic state”). Half of the patients (6/12) reported some omissions (“lack of anticipation”, “when I am better, I accidentally forget”, “on holiday”). Six out of the 12 criticized their treatment (“taking it every day makes it something special”, “heavy”, “difficult to accept”), and three still hoped for a permanent cure (“one day I might be able to stop it”, “hope to recover”).

Insight

Every subject adequately named their disease (12/12) (“bipolar disorder”, “manic depressive illness, better transcribe the pathology”). Most of them had good theoretical and clinical knowledge (10/12) (“a radical change affecting our emotions”, “abnormal mood elevation”). Eight out of the 12 (8/12) knew the etiopathogenic factors and all of them underscored the developmental difficulties that weakened their personality (“very great need to be recognized and loved”, “emotional shocks not acknowledged”, “contradictions in my personality”).

Ability to self-assess mood

Nine patients (9/12) believed they could self-assess their mood (“assessment of previous experiences”, “more aware of mild alerts”) “except during the manic episode” (9/12) (“During manic phases (or “during a high”), I don’t know if I would be able to assess the state of my mood”, “During mania I can’t do it, you’re right!”).

Discussion

We present the results of the cases that, contrary to popular belief, treatment disruption is not due to manic episode nostalgia in BDI. Shame and regret were the main sentiments and most of the patients criticized this state and found it difficult to realize that there was a problem during the course of the episode. More precisely, the initial pleasure or social and intellectual feelings were not denied but isolation and growing disorganization (exhaustion, feeling ill, loss of control) as well as later awareness of its illusory and ephemeral nature tarnish the memory, not to mention the undesirable consequences and awareness of having taken risks (some patients were happy and surprised to find they were safe). Most of the patients were observant and were knowledgeable about their disorder, with a trusting relationship with their psychiatrist (even if a minority still thought that they could permanently recover from bipolar disorder).

For most patients, treatment disruption was not intentional and was rather linked to mood elation, triggered by particular situations (high narcissistic tension or intense affective stimuli). Indeed, insight was modified by mood elevation itself “we don’t realize what we are, are doing and becoming …”. Manic episodes occupy a particular place in the patient’s history as a kind of unusual, unreal experience.

We assume that describing from the patient point of view, this mood elation (ie, keeping in mind patients’ representations about former manic state) will help the practitioner to be more persuasive as he is closer to patients owns feelings. That is why we tried to describe more precisely the progress of the manic episode, divided here into nine stages. Initially the context is characterized by a tension: a situation or event involving the subject’s history and future (narcissistic stress) creates a performance anxiety with a threat of breakdown (doubt of one’s value and abilities). The first stage involves a kind of liberation. This crisis is relieved by the generation of a sudden and paradoxical euphoric state: all the usual existential anxiety has past and the patient is convinced that he is better and can stop the treatment. Second, an intense feeling of well-being, a jubilation, is felt like a revelation; even if the patient still has some insight, he often denies the existence of a pathological state. The strength of these feelings then becomes so intense that they lead to disorganization, and the subject describes an increasing feeling of illness, exhaustion. Self-perception and control are very disturbed. This leads to an inevitable rupture: hospitalization is often decided and the person initially revolts and tests the care structure. This is followed by a long period which the patient does not remember, as if there was a dissociation. This period gives way to reconciliation with reality. The first memories therefore were related to therapeutic activities, outings, and perhaps visits from relatives. This is perceived as a soothing and pleasant return to euthymia: the subject is welcomed and recognized for their own values again. Next comes confrontation: the patient faces the painful consequences of the episode and sometimes suffers from depressive symptoms. This reminds him of his vulnerability. Consequently, a sort of projection develops: the patient criticizes the medications and their adverse effects as well as medical competence and diagnostic reliability. After several episodes and psychoeducation, this stage is often replaced by acceptance. Adherence may thus depend on acute clinical state (degree of elation) and also the final degree of acceptance.

These testimonies confirm former descriptions. In 1933, Binswanger had already written about the singularity of this subjective experience, specifying that it did not represent triumph seeking but was more of a suppression of weight, marked by optimism and volatility, with no serious worry.18 Henri Ey talked about an upset in the general structure of mind, which no longer takes time or other constraints into account.19 This leads to a loss of the ability to think, weigh things up. Indeed, Ey describes a positive part, including fiction, impulsion, and social gaming, and a negative part involving reflection’s inhibition and insight impairment. Those descriptions highlight the hypothesis of a loss of caution associated with mood elation and contributing to treatment retrieval.

Adherence may thus be impacted by the following:

- A quick loss of relational capacities. Although enhanced sociability is initially one of the most positive parts of this experience, the relational dimension is quickly lost. As observed in addiction, reward is experienced even outside any relationship.

- An inadequate firing of reward system in response to self-esteem regulation needs (depending on the subject’s narcissistic status and beliefs). The remedy for existential anxiety (withdrawal of constraints) evolves for itself but does not reach its goal and do not take into account relevant external feedback like real rewards from the environment, via therapeutic mediation for example, and family help. A predominance of goal-directed determined emotions (including drive, motivation, reward, punishment) produces an impression of control or an incitement to explore the environment. This could lead to misinterpretation of the value the subject assigns to himself and the environment, the value he feels the environment assigns to him, and the “objective” value the environment actually assigns to him through real feedback from relatives and society.

- An impairment of self-awareness process and “self-knowledge” (knowledge of subject’s own identity based on memory, planning, thought, and the inhibition of automatic responses).

A consequence of all those factors is an escape to a personal narrative process or to a social discourse that can contribute to poor adherence. A concrete application of these findings will be the systematic integration of the manic episode narration in the patient’s own personal biography in order to restore identity continuity which is mandatory for a good insight and thus necessary for compliance. Indeed, these patients are likely to find it difficult to plan for the future because they distrust their own emotions and suffer from a loss of self-confidence. Most patients avoid thinking about it and prefer to plan for the future. Those who do think about it, take it as an aspect of their personality or describe it as a ridiculous accident. Others have great difficulty in incorporating it in their personal history.

Interestingly, the combined effects of treatment, family intervention, concrete therapeutic activities, and external constraints (eg, couple separation and professional problems) promoted reconnection with reality during the episode. It is therefore important to note that remembering and narrating an episode restarts at the precise moment when relatives reestablish contact with the patient. Furthermore, the period of hospitalization is a particular event: the subjects remembered that they were first in revolt and then sometimes forgot what happened in the psychiatric care unit for several weeks. Eventually, hospitalization helped awareness of their pathological condition.

Psychoeducation should focus on both positive and negative dimensions of acute mania as explained earlier. Preventing patients from stress and providing better information about manic episode triggers and their course is important to avoid early loss of insight. Thus, developing coping strategies to enhance self-esteem, relieve anxiety, and help maintain or reinforce treatment in those situations should help to prevent relapse. As it was intended in depression, further research is needed to create instruments to assess the phenomenology of mania.20 Eventually, a standby and information device should be offered as well as involving family in the care process. It is also useful to remember the importance in primary care of the education of patients as well as care managers, and the quality of the doctor/patient relationship to manage quickly early mood elevation symptoms that can cause primary loss of insight responsible for low adherence. There may also be some implications for general practitioners, since a significant proportion of bipolar patients prefer primary care for their follow-up.21

This study had several limitations. The sample size was small, and the patients included by colleagues probably had a quite good level of insight (selection bias). Moreover, we could not exclude memorization bias given the fact that the last episode occurred on average 2.8 years before the interview. We assume that this sample presented quite accurate remembrance of the episode. The mean age of the sample and euthymia limited the bias of cognitive impairment previously described in that population.22 We must take into account the fact that some impairment of autobiographical memory has already been described in stable bipolar I patients related to executive functions not assessed here.23 Moreover, medication, thought disorganization, or loss of the usual references during the most acute stage could explain some gaps in narration. We did not notice any description of psychotic symptoms in the patients’ stories despite the fact that these are common in manic states. Was this due to a particularity of that sample or because acute awareness destructuring did not permit memorization? This work deals with euthymic patients suffering from BDI and is not generalizable to other subtypes of bipolarity.

Conclusion

Manic nostalgia was neither a predominant dimension of this retrospective narration of a manic episode nor a cause of treatment disruption in this population of euthymic patients suffering from BDI. Noncompliance should rather have been related to the start of mood elevation following a particular life event/situation. It is certainly true that the initial experience is pleasant, but it is then severely damaged by the negatives consequences of this pathological episode. Telling the story of this special experience can have many advantages: improving the doctor–patient relationship, reinforcing identity, and facilitating psychoeducation. Taken together, these parameters could lead to fewer relapses and faster acceptance of the disease. Moreover, speech analysis can be a powerful tool to try to conciliate clinical observation, patient subjectivity, and physiopathological hypothesis. These preliminary observations still have to be confirmed and compared with depressive and mixed states, as well as other bipolar disorder subtypes. We may thus expect that in type II features, there is likely to be more nostalgia related to hypomanic episodes and less awareness impairment, with very different impact on the reasons for treatment disruption.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, Katon WJ. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):19–25. | ||

Tsai SM, Chen C, Kuo C, Lee J, Lee H, Strakowski SM. 15-year outcome of treated bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2001;63(1–3):215–220. | ||

Levin J, Tatsuoka C, Cassidy K, Aebi M, Sajatovic M. Trajectories of medication attitudes and adherence behavior change in non-adherent bipolar patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:29–36. | ||

Col SE, Caykoylu A, Karakas Ugurlu G, Ugurlu M. Factors affecting treatment compliance in patients with bipolar I disorder during prophylaxis: a study from Turkey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(2):208–213. | ||

Chang C-W, Sajatovic M, Tatsuoka C. Correlates of attitudes towards mood stabilizers in individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):106–112. | ||

Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Amann BL, Nivoli AMA, Vieta E, Colom F. Treatment adherence in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):1003–1008. | ||

Pompili M, Venturini P, Palermo M, et al. Mood disorders medications: predictors of nonadherence – review of the current literature. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(7):809–825. | ||

Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, Cassidy K, Tatsuoka C, Jenkins J. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(3):280–287. | ||

Jamison KR, Gerner RH, Goodwin FK. Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium: relationship to compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(8 Spec No):866–869. | ||

Morselli PL, Elgie R; GAMIAN-Europe. GAMIAN-Europe/BEAM survey I-global analysis of a patient questionnaire circulated to 3450 members of 12 European advocacy groups operating in the field of mood disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(4):265–278. | ||

Pope M, Scott J. Do clinicians understand why individuals stop taking lithium? J Affect Disord. 2003;74(3):287–291. | ||

Marková IS, Jaafari N, Berrios GE. Insight and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a conceptual analysis. Psychopathology. 2009;42(5):277–282. | ||

Ghaemi SN, Rosenquist KJ. Is insight in mania state-dependent?: A meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(11):771–775. | ||

Shad M, Prasad K, Forman S, et al. Insight and neurocognitive functioning in bipolar subjects. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:112–120. | ||

Lobban F, Taylor K, Murray C, Jones S. Bipolar disorder is a two-edged sword: a qualitative study to understand the positive edge. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):204–212. | ||

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies in Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction; 1967. | ||

Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: an explication and introduction. In: Emerson RM, editor. Contemporary Field Research. Boston: Little, Brown; 1983:109–126. | ||

Binswanger L. Sur La Fuite Des Idées. Grenoble: Jérôme Millo; 1933. | ||

Ey H. Etudes Psychiatriques [Psychiatric studies]. Perpignan: Crehey; 1954. French. | ||

Stoleru S, Kosmadakis C, Coudert O, Degras D, Allilaire JF. Evaluating major depressive episodes through the algorithmically structured systematic exploration of subject’s state of mind. Psychopathology. 2010;43(1):41–52. | ||

Cerimele JM, Halperin AC, Spigner C, Ratzliff A, Katon WJ. Collaborative care psychiatrists’ views on treating bipolar disorder in primary care: a qualitative study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):575–580. | ||

Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1–3):105–115. | ||

Kim WJ, Ha RY, Sun JY, et al. Autobiographical memory and its association with neuropsychological function in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):290–297. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.