Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 18

Associations between Internet Addiction, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Maternal Depression and Anxiety in Clinically Referred Children and Adolescents

Authors Sakamoto S, Miyawaki D, Goto A, Hirai K, Hama H, Kadono S, Nishiura S, Inoue K

Received 21 July 2022

Accepted for publication 30 September 2022

Published 21 October 2022 Volume 2022:18 Pages 2421—2430

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S383160

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Taro Kishi

Shoko Sakamoto,1,2 Dai Miyawaki,1 Ayako Goto,1 Kaoru Hirai,1,3 Hiroki Hama,1,2 Shin Kadono,1,2 Sayaka Nishiura,1,2 Koki Inoue1

1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan; 2Department of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan; 3Department of Pediatrics, Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan

Correspondence: Dai Miyawaki, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, 545-8585, Japan, Tel +81-6-6645-3821, Fax +81-6-6636-0439, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Internet addiction (IA) has become a global problem and is one of the most common reasons for children to be referred for intervention because IA results in social and educational dysfunction and conflict with parents. IA is associated with various comorbid psychiatric disorders, with notable association between IA and family factors. However, little is known about parental psychopathology. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of IA and association between IA and maternal depression and anxiety in clinical samples after adjusting for comorbidities.

Patients and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted between April 2020 and August 2021 at the Department of Neuropsychiatry of Osaka Metropolitan University Hospital in Japan. A total of 218 clinically referred children and adolescents (aged 8 to 15 years) were assessed using the Internet Addiction Test, which is one of the most popular questionnaires to evaluate IA, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), and The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version. IA was defined as a total score on the Internet Addiction Test ≥ 50. Of those, for the evaluation of maternal depression and anxiety, the 132 mothers of the children who were referred after January 2021 completed K6 as well.

Results: A total of 68 participants (31.2%) presented with IA and had higher total and externalizing scores of CBCL, social anxiety disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder compared to those without IA. IA was associated with the six-item Kessler scale scores of mothers, being raised by single parents, and anxiety disorders after adjusting for age, sex, and family income (95% CI: 1.023– 1.215).

Conclusion: Maternal depression and anxiety may be one of the risk factors for children and adolescents to develop IA. Care for maternal depression and anxiety may contribute to intervention for children and adolescents with IA.

Keywords: internet addiction, children, maternal depression, oppositional defiant disorder, social anxiety disorder

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

A Response to Letter by Dr Teixeira Filho has been published for this article.

Introduction

The incidence of internet addiction (IA) has increased,1 and it is associated with a variety of comorbid psychiatric symptoms, including depression,2–7 anxiety,2,6,8 impulsivity,4,6 hyperactivity, behavioral problems,5,9 aggression,6,10 and sleep disturbances.10 It has become a global problem with a prevalence of 4.2% to 23.7% depending on the age of the participants and various methods of assessing IA.5,9,11–21 Family factors, such as growing up with a single parent22 and low family income,23,24 are also associated with IA in childhood and adolescence. Recently, some studies suggested IA in adolescence was associated with parental depression.25,26 However, little is known about the association between IA in clinical population and parental depression, especially in childhood. Most surveys of IA used self-reported questionnaires for non-clinical adolescents.24,5–10 leading to a lack of controlling for the effect of psychiatric comorbidities with dysfunction in daily life. Additionally, few studies on psychiatric comorbidities with IA in a clinical population did not employ reported family factors as confounding factors.23–29

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of IA and psychiatric comorbid diagnoses in childhood and adolescent clinical cases. We hypothesized that IA would be associated with depression and anxiety in mothers, who are the primary caregivers in Japan, even after controlling for psychiatric comorbidities and other family factors, including being raised by a single parent and low income.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The eligible participants were 276 children (aged 8–15 years) who were consecutively referred to the psychiatric outpatient clinic of the Osaka Metropolitan University (Osaka, Japan) between April 2020 and August 2021. Of those, the 132 mothers of the children referred after January 2021 were included in the study of maternal depression and anxiety. According to the exclusion criteria, children with intellectual disabilities (n = 21; IQ < 70 based on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third or Fourth Edition), those with acute psychotic or manic states (n = 6), those with severe neurological impairments or refractory epilepsy (n = 4), children without parents (n = 6), those who did not provide assent/consent to participate in the study (n = 10), and those who did not complete all assessments (n = 11) were excluded. Therefore, the remaining 218 children were included in the study.

Socioeconomic status is significantly associated with health status.30 Here, we conducted interviews to collect information on parental absence (ie, the absence of either the father or the mother), family income, and years of parental education. Regarding family income, we categorized households receiving public assistance or with an annual income < 3 million yen as having low income.

All children and their mothers provided written informed assent/consent before participating in the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine. The research was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Measures

Internet Addiction Test

The Internet Addiction Test (IAT) is a self-report questionnaire comprising 20 questions with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 5 (always).31 It has been translated into various languages and is one of the most widely used scales for evaluating IA.32,33 Scores on the IAT range from 20 to 100 (20–49 reflecting normal internet use, 50–79 moderate internet use, and 80–100 severe internet use).34–40 A screening score of 50 on the Japanese version of the IAT (JIAT) has been proposed as a cut-off.41 The JIAT has shown good reliability and validity.17,41,42 In our study, we considered a JIAT total score of ≥ 50 as IA., and that of < 50 as non-IA.

Child Behavior Checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a standardized questionnaire for parents to rate the frequency and intensity of 113 behavioral and emotional problems exhibited by their children over the last six months.43 Parents’ responses are recorded on a 3-point scale (0, 1, and 2 indicated that the behavior is not true, somewhat or sometimes true, or very often or often true, respectively). The CBCL factor structure consists of eight narrow-band problem scales (Withdrawal, Somatic Complaints, Anxious/Depressed, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Delinquent Behavior, Aggressive Behavior), two broadband scales (Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems), and a Total Problems scale that is the sum of all subscales. The T score of these two subscales and the total scale were calculated using a standardized distribution of Japanese children.44

The 6-Item Kessler Scale

The K6 is commonly used for assessment of psychological distress with six questions where participants are asked to rate how often they have felt “nervous”, “hopeless”, “restless or fidgety”, “so depressed that nothing could cheer you up”, “that everything was an effort”, and “worthless” during the past 30 days. Response options include “0 – none of the time”, “1 – a little of the time”, “2 – some of the time”, “3 – most of the time”, and “4 – all of the time.” The range of scores for the K6 is thus from 0 to 24. The Japanese version of the K6 has shown good reliability and has been validated in the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey.45–47 The optimal cutoff for the K6 has been set at 12/13 for balancing false-positive and false-negative results.45,47

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to assess current and past episodes of psychopathology in children and adolescents according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM)-IV-Text Revision (TR) criteria.48 Each item is endorsed as present, absent, or unknown. The diagnostic algorithm is implemented following international guidelines. The K-SADS-PL psychometric properties have been estimated as excellent in prior work, with high inter-rater reliability (k = 0.93) and high test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.74–0.90).49 The Japanese version, K-SADS-PL-J, has consistently demonstrated good inter-rater reliability and high concurrent validity across studies.48

Procedure

Participants referred to the clinic were assessed by a trained multidisciplinary team, including experienced child psychiatrists, psychologists, and a psychiatric social worker. Initially, participants were interviewed for sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, absence of father or mother, family income, years of parental education, and internet use habits. Then, 218 children and parents were interviewed in joint and separate sessions for the psychiatric assessment using K-SADS-PL-J. Children completed the IAT questionnaire, and mothers completed the CBCL assessments. Of those, for the evaluation of maternal depression and anxiety, the 132 mothers of the children who were referred after January 2021 completed K6 as well. After completing the evaluation, a multidisciplinary team meeting was held to decide the most appropriate diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of data was performed using SPSS software (version 26.0.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). In the evaluation of the data determined by measurement, Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables based on whether parametric test assumptions were met or not, respectively. The Pearson’s chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests (where expected values were < 5) were used to compare categorical variables between groups of children with IA and non-IA. Associations of K6 scores of mothers whose children had IA were estimated using binomial logistic regression models after controlling other factors associated with IA (age, sex, family income, single-parent family, any mood disorders, anxiety disorders, or behavioral disorders). Two-sided tests were performed, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 68 children (31.2%) had IA. Table 1 presents the comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the two groups (IA and non-IA/control group). The average age of children was 13.1 ± 1.8 years old, and 112 (51.4%) of them were boys. The two groups had non-significant differences regarding age and sex distribution. Single-parent families were significantly more prevalent in the IA group than in the control (non-IA) group (32.4% vs 14.0%, p = 0.002). Social anxiety disorder (SAD) and oppositional defiance disorder (ODD) were significantly more prevalent in the IA group than in the control group (25.8% vs 11.3%, p = 0.009; 29.0% vs 14.1%, p = 0.012) (Table 2). The total and externalizing scores were significantly higher in the IA group than in the control group (68.8 vs 64.7, p = 0.006; 63.4 vs 58.3, p = 0.001, respectively) (Table 3). Regarding the CBCL subscales, three of the eight subscale scores (withdrawn, delinquent behavior, and aggressive behavior) were significantly higher in the IA group than in the control group (69.2 vs 65.8, p = 0.049; 62.6 vs 58.2, p = 0.001; 62.6 vs 58.8, p = 0.005, respectively). Child/adolescent comorbidities are described for the IA and control groups in Tables 2 and 3.

|

Table 1 Participants’ Sociodemographic Characteristics |

|

Table 2 K-SADS-PL Diagnoses for the Internet Addiction (IA) and Control Groups |

|

Table 3 CBCL T Scores for the Internet Addiction (IA) and Control Groups |

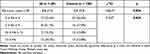

The K6 scores of mothers were significantly higher in the IA group than in the control group (36.4% vs 14.6%, p = 0.029; 76.5 vs 59.7, p = 0.010, respectively) (Table 4). K6 scores above 13 suggest severe anxiety and depressive symptoms, which were significantly higher in the IA group than in controls.

|

Table 4 Comparison of the K6 Score of Mothers Between the Internet Addiction (IA) and Control Groups |

In Table 5, because K6 score of mothers was used as an independent variable in addition to age at the consultation, sex, single parent status, low family income, and any mood, anxiety, or behavioral disorders that were found to have an association with IA. IA could be predicted by the K6 score of mothers (Exp(B) = 1.115; p = 0.013), single parent status (Exp(B) = 6.518; p=0.010), and any anxiety disorders (Exp(B) = 4.463; p = 0.012). Every 1-point increase in the mother’s total K6 score, increases the likelihood of a child’s IA by 1.115 points.

|

Table 5 Results of Binary Logistic Regression Analysis Showing Predictors of Total K6 Scores in the Internet Addiction (IA) Group (n =119) |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that IA in clinically referred children and adolescents is associated with maternal depression and anxiety, in addition to single parent status and comorbid anxiety disorders, even after adjusting for other factors, including psychiatric comorbidities and family factors. In this study, we found IA in approximately 30% of clinical cases of children and adolescents, indicating that this group is more likely to have comorbid SAD and ODD.

This study supports the hypothesis that IA is associated with maternal depression and anxiety in clinical children and adolescents. Past studies on a community sample also suggested that parents of adolescents with IA showed depression and anxiety.25,26 These studies were conducted in the general population with relatively mild parental depression and anxiety symptoms, but they support our hypothesis. Although the mechanism of the association of IA and maternal depression and anxiety remains unclear, considering that previous studies have shown that maternal depression was likely to negatively impact mother-child relationships50 and that poor communication between parents and adolescents was associated with IA,51 maternal depression may make their child vulnerable to developing IA.

We found IA in approximately 30% of clinical cases of children and adolescents. Considering the prevalence of IA in the non-clinical adolescents, it varies from 4.2% to 23.7% according to the age of participants and IA assessment methods.5,9,11–21,52 Considering the prevalence of IA in clinical adolescents, which is naturally higher than in the general population, 46% of Japanese patients with autism spectrum disorder aged 10–19 (the mean age of the participants was 13.4 years),53 33.7% of Turkish patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 76% of whom were boys) aged 12–18 with a mean age of 14.3 years had IA.54 On the other hand, considering clinical children and adolescents, 11.3% of psychiatric inpatients in Germany55 had IA. Since our sample included elementary school students, the prevalence of 30% in this study is consistent with previous studies for a clinical population that showed a relatively high prevalence in adolescence and low prevalence in childhood.

Considering the psychiatric comorbidity of IA, this study showed that mood, behavioral, and anxiety disorders were more prevalent in the IA group, with significant differences in SAD and ODD prevalence compared to those in the control group. Previous studies found that IA was significantly associated with depression, social anxiety, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and behavioral problems such as aggression.5–7 These studies on IA comorbidities in adolescents are based on responses to self-report questionnaires. A Turkish study using the K-SADS-PL found that 30% of adolescents with IA had major depressive disorder, 35% had SAD, 83% had ADHD, and 23.3% had ODD.56 In the present study, SAD was significantly more prevalent in the IA group. This could be because internet use enables patients with SAD to spend time without face-to-face communication, which could be a coping skill, resulting in IA. We recommend that clinicians should consider IA in children and adolescents presenting with SAD. Univariate analysis showed that ODD was significantly more prevalent in the IA group, consistent with previous reports.5,56 Previous studies showed a higher prevalence of ADHD comorbidity in IA groups,5–7,56,57 which we did not find here. Furthermore, our multivariate analysis showed that behavioral disorders, including both ADHD and ODD, were not significantly associated with IA. Considering that most previous studies have not examined socioeconomic factors, low background socioeconomic status may affect the occurrence of IA. In addition, it could be because previous studies had a higher proportion of boys in their study populations, who are more likely to have ADHD;58,59 the present study, however, had a male-to-female ratio that was approximately equal. Also, unlike previous studies, our results did not show a significant difference in the comorbidity rates of major depressive disorder, which was slightly lower in the IA group (12.9%). This may be because our study included younger children who were younger than the age at which depression is more likely to occur. The prevalence of IA is higher in treatment-seeking children and adolescents than in the general population, especially in patients with SAD and ODD. Therefore, focusing on IA in children at an early age and screening their mothers for depression and anxiety disorders is essential.

The present study had a few limitations. First, because we included a relatively small sample of treatment-seeking outpatients from a single medical institution, we cannot generalize these results to the general population. However, Japan has a universal health insurance system, and our hospital accepts various patients consecutively. Therefore, sampling bias was minimized to a certain extent. Second, because this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot conclude a causal relationship between IA in children and maternal depression and anxiety. Third, only mothers were included in the study, and fathers were not investigated for depression and anxiety. However, previous studies have shown no association between paternal depression and child IA.25 Moreover, we adjusted for paternal absence and family environments, including annual income. Fourth, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic might have increased IA in children due to shutdowns and lockdowns. However, since all participants were recruited after the start of the pandemic, this might not have affected results on an individual level. Furthermore, a report showed that school closures during the pandemic did not significantly increase potential mental health problems in children in Japan.59 Therefore, the effect of the pandemic on our results was likely negligible. Finally, we used the K-SADS-PL, which is based on the DSM-IV-TR. Since the Japanese version of K-SADS that conforms to DSM-V has not been standardized, we used the available standardized K-SADS-PL-J.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that IA in children is associated with maternal depression and anxiety, in addition to single parent status and comorbid anxiety disorders in clinical settings, even after adjusting for children’s comorbidities and family environmental factors. Maternal depression and anxiety could be one of the risk factors for children and adolescents for developing IA. In clinical cases of children and adolescents, focusing on IA problems at an early age is mandatory, especially in those with SAD or ODD. In children with IA, care for maternal depression and anxiety and an attention to psychiatric comorbidities and family factors is needed. Since there are no established diagnostic criteria for IA, there is a need to develop a validated structured diagnostic questionnaire for IA. In addition, a multicenter longitudinal study is warranted to investigate comorbidities using the DSM-V-compliant K-SADS diagnosis criteria and to include paternal psychopathology for determining causal relationships between IA in children and maternal depression.

Abbreviations

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders-IV-Text Revision; IA, internet addiction; IAT, Internet Addiction Test; JIAT, Japanese version of the Internet Addiction Test; K6, six-item Kessler scale; K-SADS-PL, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version; ODD, oppositional defiance disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; WMH, World Mental Health.

Data Sharing Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

All children and their mothers provided written informed assent/consent before participating in the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine. The research was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP20K03002).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

1. Khalil SA, Kamal H, Elkholy H. The prevalence of problematic internet use among a sample of Egyptian adolescents and its psychiatric comorbidities. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(2):294–300. doi:10.1177/0020764020983841

2. Yen CF, Chou WJ, Liu TL et al. The association of Internet addiction symptoms with anxiety, depression and self-esteem among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1601–1608. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.05.025

3. Kim K, Ryu E, Chon MY, et al. Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relation to depression and suicidal ideation: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):185–192. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.005

4. Lin MP, Ko HC, Wu JYW. Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with Internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(12):741–746. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0574

5. El Asam A, Samara M, Terry P. Problematic internet use and mental health among British children and adolescents. Addict Behav. 2019;90:428–436. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.007

6. Obeid S, Saade S, Haddad C, et al. Internet addiction among Lebanese adolescents: the role of self-esteem, anger, depression, anxiety, social anxiety and fear, impulsivity, and aggression-A cross-sectional study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(10):838–846. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001034

7. Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS et al. Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):937–943. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159

8. Karaer Y, Akdemir D. Parenting styles, perceived social support and emotion regulation in adolescents with internet addiction. Compr Psychiatry. 2019;92:22–27. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.03.003

9. Cao F, Su L. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: prevalence and psychological features. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33(3):275–281. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00715.x

10. Kuss DJ, Kristensen AM, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addictions outside of Europe: a systematic literature review. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;115:106621. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106621

11. Durkee T, Kaess M, Carli V, et al. Prevalence of pathological internet use among adolescents in Europe: demographic and social factors. Addiction. 2012;107(12):2210–2222. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03946.x

12. Fu KW, Chan WSC, Wong PWC, Yip PSF. Internet addiction: prevalence, discriminant validity and correlates among adolescents in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):486–492. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075002

13. Kaess M, Durkee T, Brunner R, et al. Pathological Internet use among European adolescents: psychopathology and self-destructive behaviours. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(11):1093–1102. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0562-7

14. Lee JY, Kim SY, Bae KY, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for problematic Internet use among rural adolescents in Korea. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;10(2):e12310. doi:10.1111/appy.12310

15. Malak MZ, Khalifeh AH, Shuhaiber AH. Prevalence of internet addiction and associated risk factors in Jordanian school students. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;70:556–563. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.011

16. Vigna-Taglianti F, Brambilla R, Priotto B et al. Problematic internet use among high school students: prevalence, associated factors and gender differences. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:163–171. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.039

17. Yamada M, Sekine M, Tatsuse T et al. Prevalence and associated factors of pathological Internet use and online risky behaviors among Japanese elementary school children. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(10):537–544. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20200214

18. Al-Khani AM, Saquib J, Rajab AM et al. Internet addiction in Gulf countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. 2021;10(3):601–610. doi:10.1556/2006.2021.00057

19. Kawabe K, Horiuchi F, Ochi M et al. Internet addiction: prevalence and relation with mental states in adolescents. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70(9):405–412. doi:10.1111/pcn.12402

20. Mak KK, Lai CM, Watanabe H, et al. Epidemiology of Internet behaviors and addiction among adolescents in six Asian countries. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(11):720–728. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0139

21. Poli R, Agrimi E. Internet addiction disorder: prevalence in an Italian student population. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66(1):55–59. doi:10.3109/08039488.2011.605169

22. Ni X, Yan H, Chen S et al . Factors influencing internet addiction in a sample of freshmen university students in China. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(3):327–330. doi:10.1089/cpb.2008.0321

23. Faltýnková A, Blinka L, Ševčíková A et al. The associations between family-related factors and excessive Internet use in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1754. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051754

24. Lee CS, McKenzie K. Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities of Internet addiction in Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12(4):559–562. doi:10.4306/pi.2015.12.4.559

25. Choi DW, Chun SY, Lee SA et al. The association between parental depression and adolescent’s Internet addiction in South Korea. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17:15. doi:10.1186/s12991-018-0187-1

26. Lam LT. Parental mental health and Internet Addiction in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2015;42:20–23. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.033

27. Wang F, Lu J, Lin L et al. Mental health and risk behaviors of children in rural China with different patterns of parental migration: a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019;13:39. doi:10.1186/s13034-019-0298-8

28. Mun IB, Lee S. The influence of parents’ depression on children’s online gaming addiction: testing the mediating effects of intrusive parenting and social motivation on children’s online gaming behavior. Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01854-w

29. Lam LT. The roles of parent-and-child mental health and parental Internet addiction in adolescent Internet addiction: does a parent-and-child gender match matter? Front Public Health. 2020;8:142. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00142

30. Li Y, Zhang X, Lu F et al. Internet addiction among elementary and middle school students in China: a nationally representative sample study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(2):111–116. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0482

31. Kondo N, Sembajwe G, Kawachi I et al. Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: meta-analysis of multilevel studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4471. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4471

32. Young KS. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: a case that breaks the stereotype. Psychol Rep. 1996;79(3 Pt 1):899–902. doi:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.899

33. Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the Internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7(4):443–450. doi:10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443

34. Jelenchick LA, Becker T, Moreno MA. Assessing the psychometric properties of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) in US college students. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(2–3):296–301. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.007

35. Bener A, Bhugra D. Lifestyle and depressive risk factors associated with problematic Internet use in adolescents in an Arabian gulf culture. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):236–242. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182926b1f

36. Khazaal Y, Billieux J, Thorens G, et al. French validation of the Internet Addiction Test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(6):703–706. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0249

37. Younes F, Halawi G, Jabbour H, et al. Internet addiction and relationships with insomnia, anxiety, depression, stress and self-esteem in university students: a cross-sectional designed study. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0161126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161126

38. Ioannidis K, Treder MS, Chamberlain SR, et al. Problematic internet use as an age-related multifaceted problem: evidence from a two-site survey. Addict Behav. 2018;81:157–166. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.017

39. Ioannidis K, Chamberlain SR, Treder MS, et al. Problematic internet use (PIU): associations with the impulsive-compulsive spectrum. An application of machine learning in psychiatry. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;83:94–102. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.08.010

40. Aznar-Díaz I, Romero-Rodríguez JM, García-González A et al. Mexican and Spanish university students’ Internet addiction and academic procrastination: correlation and potential factors. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233655

41. Tateno M, Teo AR, Shiraishi M et al. Prevalence rate of Internet addiction among Japanese college students: two cross-sectional studies and reconsideration of cut-off points of Young’s Internet Addiction Test in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(9):723–730. doi:10.1111/pcn.12686

42. Kurokawa M, Honjo M, Mishima K. Development of the smartphone-based Internet Addiction Tendency Scale for high school students and technical college students. Jpn J Exp Soc Psychol. 2020;60(1):37–49. doi:10.2130/jjesp.1907

43. Achenbach TM, Dumenci L. Advances in empirically based assessment: revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF: comment on Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich, and Fischer (2001). J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(4):699–702. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.699

44. Itani T. Standardization of the Japanese version of the child behavior checklist/4-18. Psychiatr Neurol Paediatr Jpn. 2001;41:243–252.

45. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi:10.1017/s0033291702006074

46. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(suppl1):4–22. doi:10.1002/mpr.310

47. Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K et al. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(5):434–441. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x

48. Takahashi K, Miyawaki D, Suzuki F, et al. Hyperactivity and comorbidity in Japanese children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(3):255–262. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01651.x

49. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

50. Morgan JK, Ambrosia M, Forbes EE et al. Maternal response to child affect: Role of maternal depression and relationship quality. J Affect Disord. 2015;187:106–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.043

51. Li J, Yu C, Zhen S et al. Parent-Adolescent Communication, School Engagement, and Internet Addiction among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Effect of Rejection Sensivity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;(7):3542. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073542

52. Seyrek S, Cop E, Sinir H et al. Factors associated with Internet addiction: Cross-sectional study of Turkish adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2017;59(2):218–222. doi:10.1111/ped.13117

53. Kawabe K, Horiuchi M, Miyama T et al. Internet addiction and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;89:22–28. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2019.03.002

54. Demirtaş OO, Alnak A, Coşkun Met al. Lifetime depressive and current social anxie263 are associated with problematic internet use in adolescents with ADHD: A cross-sectional study. 10.1111/camh.12440Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;26 3 :220–227. doi:10.1111/camh.12440

55. Müller KW, Ammerschläger M, Freisleder FJ et al. Suchtartige Internetnutzung als komorbide Störung im jugendpsychiatrischen Setting. [Addictive internet use as a comorbid disorder among clients of an adolescent psychiatry – Prevalence and psychopathological symptoms]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2012;40:331–337; quiz 338–339.

56. Wang YH, Lau JTFH . The health belief model and number of peers with internet addiction as inter-related factors of Internet addiction among secondary school students in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:272. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2947-7

57. Bozkurt H, Coskun M, Ayaydin H et al. Prevalence and patterns of psychiatric disorders in referred adolescents with Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosc. 2013;67(5):352–359. doi:10.1111/pcn.12065

58. Restrepo A, Scheininger T, Clucas J et al. Problematic internet use in children and adolescents: Associations with psychiatric disorders and impairment. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):252. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02640-x

59. Saito M, Kikuchi Y, Lefor AK et al. Mental health in Japanese children during school closures due to the COVID-19. Pediatr Int. 2022;64(1):e14718. doi:10.1111/ped.14718

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.