Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 16

Assessment of the Influence of Physicians’ Attire on Surgical Patients’ Perception. Across-Sectional Study in Aabet Hospital, AddisAbeba, Ethiopia, 2021

Authors Ejigu EF, Haile AW , Bayable SD

Received 15 December 2021

Accepted for publication 23 February 2022

Published 4 March 2022 Volume 2022:16 Pages 605—614

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S353609

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Endalamaw Fentie Ejigu,1 Abiy Worku Haile,1 Samuel Debas Bayable2

1Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, St. Paul Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2Department of Anesthesia School of Medicine and Health Science Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Samuel Debas Bayable, Email [email protected]

Background: In Ethiopia, physicians commonly wear formal attire, surgical scrubs, casual attire, or business attire during patient care, but there is no evidence to show which attire is preferred within the patients. So this study aims to assess the influence of physicians’ attire on patients’ perceptions.

Methodology: After ethical approval, a cross-sectional study was conducted with written informed consent; data were collected and checked for its completeness, later entered into SPSS version 25 for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics was presented with frequency, percentage, tables, graphs, and texts based on the nature of the data. All the four attires were compared using the Friedman test and pair wise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, and Mann–Whitney U-test was used to know the preferred attire on patients’ perception about physicians’ skill, with 95% confidence and a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results: In this study, out of the total respondents 66.7% are males and 71.9%, 50.3% of the respondents were degree or diploma holders, and aged 18– 34 years respectively. Among participants’ 77.1% and 55.9% preferred formal attire and surgical scrub respectively. For male surgeons, formal attire and surgical scrub have an equal preference in surgical patients (p< 0.001), but business and casual attire have no statistically significant difference. The patients’ preference in male formal physician attire in surgeon’s confidence, willingness to discuss confidential information and safeties of the surgeon were 76.2%, 75.7%, and 70.5% respectively, and for female surgeons, formal attire on surgical patients’ confidence in the surgeon, safety, and willingness to discuss confidential information were 74.9%, 73.8%, and 71.8% respectively.

Conclusion: Physician attire is one of the important factors that inspire surgical patient confidence, smartness, surgical skill, discussion of confidential information, and caring ability in physicians. Formal attire and surgical scrub were the most preferred physician’s outfits.

Keywords: physician attire, patient confident, patient trust, patient perception

Background

Even though physicians’ attire started with Hippocrates’ suggested that physicians should “be clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet-smelling unguents” it formally begins in the late 19th century.1,2

The white coat physician attire is used in the 20th century all over the world and become uniform for physicians.1,3–5 The “white coat ceremony ” was first introduced by Arnold P.Gold Foundation of Columbia University College of physicians and surgeons in 1993.6

Physicians’ dressing code is one of the symbols of professionalism that improves the patients’ trust and satisfaction.7–9 Dressing in an unexpected and unmannered way creates mistrust and bad feelings about physicians’ ability to treat and care.10

Patient-physician relationships both verbal and nonverbal communications are important to disclose medical history including sensitive issues that are important for diagnosis and treatment.11 Building good communication and relationship between patients and caregivers play a great role,5,11 to increase trust and confidence in the diagnosis and treatment, and highly likely to return on appointment.12,13

A study done in the USA in orthopedics outpatient setting found that in male surgeons, white coat induces good perception on the patient regarding physicians’ confidence, intelligence, and safety whereas in female surgeons white coat was rated equally to scrubs.4 The physicians’ attire that influences patients’ perception is different from person to person due to different reasons like age, educational status, culture, country.5,14

Statement of the Problem

Nowadays different institutions and countries have their dressing codes and research on patients “perception on their physicians” attire were varied based on age, setting, and educational status.3,14 Even if, white coat physician attire is perceived as a symbol of a physician, professional, hygienic, easily identifiable, and scientific,4–6 currently there are several complaints against the use of this attire due to infection transmission risk.3,4,6,14,15

Unprofessional physicians’ attire, may affect patients’ perception about the diagnosis and treatment that make them not take medications correctly, not follow physicians’ advice, or miss from follow-up, making the patient dissatisfied with the care they got and the hospital at all. In Ethiopia, physicians commonly wear four attires, but the patients’ preference and its effect on patients’ perception are not known due to lack of study. So this study aims to assess whether physicians’ attire influences patients’ perception or not.

Justification of the Problem

A physician’s attire is important to building a good physician-patient relationship,14,15 which is crucial for patient care.4–6,8 Studies showed that about 76.3% of the study participants prefer their physician to wear formal attire with a white coat followed by surgical scrubs.8,16

In Ethiopia, it is common to see physicians wearing scrubs, casual attire with the white coat, formal attire with a white coat, or casual attire only, but there is no previous study about physicians’ attire and patients’ perception, so assessing physicians’ attire on patient perception, improves the physician-patient relationship.16

Objectives

General Objective

The aim of the present study was to determine the influence of physicians’ attire on surgical patients’ perception, in Aabet hospital, AddisAbeba, Ethiopia, 2021.

Specific Objective

To assess the influence of physicians’ attire on surgical patients’, trust, confidence, smartness, surgical skill, discussion of confidential information with their primary physician, caring ability of the surgeon, and trustworthiness with their doctors.

Methodology

After ethical approval was obtained from St Paul millennium medical college ethical review board (StPMMC107/2021), a prospective cross-sectional study was conducted with written informed consent from each participant, patients having vision/hearing problems, patients in pain, unable to communicate were excluded from this study.

A self-administered questionnaire was administered, having 3 parts; the first part contains demographic characteristics of the participants including age, sex, educational status, and residency, the second part contains four male and four female photos shown one by one and under each photo, seven questions (How confident are you in this surgeon? How smart is this surgeon? How well do you think the surgery will go if this was your surgeon? How willing are you to discuss confidential information with this surgeon? How trustworthy is this surgeon? How safe is this surgeon? How is the caring ability of this surgeon?), were asked through a five-point Likert scale (Figure 1), To decrease bias all physicians’ photographs had the same background, name tag, stethoscope position, physical appearance, and the third part contains all the four attires of male and female physicians and the participants asked to order the photo based on the skill of the physicians from higher qualified to less qualified.

The collected data were checked for its completeness, later entered into SPSS version 25 for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were presented with frequency, percentage, tables, graphs, and texts based nature of data. All the four attires were compared using the Friedman test and pairwise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, and Mann–Whitney U-test was used to know the preferred attire on patients’ perception about physicians’ skill, with 95% confidence and a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Operational Definitions

Attire/outfit= clothes.

Formal attire= white coat with T-Shirt, and necktie.

Scrubs= is a short sleeve shirt and trousers worn by surgeons, nurses, physicians, and other workers involved in inpatient care in hospitals.

Casual attire= was relaxed, occasional, spontaneous, and suited for everyday use.

Results

In this study, the mean age of respondents was 36.9 years and out of the total (366) respondents 66.7% were males, of which 71.9%, 50.3%were aged 18–34 years, and degree/diploma holders, respectively as shown in (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Surgical Patients’ Perception on Physician Attires at Addis Ababa Burn, Emergency, and Trauma (Aabet) Hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366) |

Surgical Patients Preferences Regarding Physicians’ Attire

Out of the total male respondents (245) majority of respondents,77.1% and 55.9% prefers formal attire and surgical scrub respectively, while in female respondents prefers 71.9% and 76.8% of the two attires respectively as shown in (Table 2).

Comparison of Respondents on Male Surgeons’ Attire

For male surgeons, formal attire is more preferred across respondents compared to business, and casual attire. But formal attire and surgical scrub have equal preference except discussing confidential information (p=0.013). Business attire and casual attire have no statistically significant difference in preference among the participants (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Comparison of Four Commonly used Male Physician Attires at Addis Ababa Burn, Emergency, and Trauma (Aabet) hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366) |

The patients’ preference for formal physician attire in male surgeons’ confidence, willingness to discuss confidential information, and safeties of the surgeon to do the procedure were 76.2%, 75.7%, and 70.5% respectively, while scrub physician attire choice of patients on the caring ability of the surgeon, confidence of the surgeon, and willingness if he is his/her surgeon were 65%, 64.2%, and 58.5% respectively as shown in (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 The impact of male formal physician attire and scrub physician attires on surgical patients’ perception at Addis Ababa burn, emergency, and trauma (Aabet) hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366). |

Both business and casual attires are the least preferred and have less confidence, smartness of the surgeon, dissatisfied if he is his/her responsible surgeon, not willing to discuss confidential information, give less value on the skill, and caring ability (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 The impact of male business physician attire and casual physician attire on surgical patients’ perception at Addis Ababa burn, emergency, and trauma hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366). |

Comparison of Female Surgeons’ Attire

For female surgeons’ attire, formal attire and surgical scrubs have more preference across all categories compared to business and casual attire. Formal attire and surgical scrubs have no statistically significant difference in preference across all categories. There is no difference in preference among respondents between business attire and casual attire (Table 3).

For female surgeons, formal physician attire on surgical patients’ confidence in the surgeon, safety of the surgeon if she performs the procedure, and willingness to discuss confidential information were 74.9%, 73.8%, and 71.8%respectively, which is the same with scrub physician attires as shown in (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Choice of surgical patients on formal and scrub physician attires for female surgeons’ at Addis Ababa burn, emergency, and trauma hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366). |

As stated for male physicians business and casual attires for female physicians are the least preferred and has less confidence, smartness of the surgeon, dissatisfied if she is responsible surgeon, not willing to discuss confidential information, give less value on the skill, and caring ability as shown in (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5 The influence of business and casual female physicians attires surgical patients’ perception at Addis Ababa burn, emergency (Aabet), and trauma hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366). |

Patient Preference of Physician Attires Based on Surgeons’ Skill

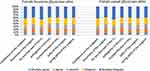

For male surgeon attire, 82% of the participants prefer formal attire as their first choice, while for female surgeons 74% respectively based on surgeons’ skill as shown (Figure 6).

|

Figure 6 Preference of respondents’ on physician attire based on surgeons’ skill for male and female surgeons’ at Addis Ababa burn, emergency, and trauma hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366). |

Discussion

The physician-patient relationship is basic in medical care and affected by multiple factors including culture, social norms, and physician professionalism. Before the Patients gain any clinical care they are impressed with their physician’s verbal and nonverbal communication, as well as physician’s appearance including attiring, and cleanliness.12

In this study, it was observed that the patients preferred both male and female primary care physicians wearing formal attire (white coat with T-Shirt, and necktie). These preferences are similar with previous studies’ findings.15,17–19 in addition, formal attire and surgical scrubs are the most preferred attires across among participants compared to business and casual attires (p<0.001) as shown in (Tables 3 and 4), which is inline with most previous studies,4,11,20,21 but a study in South Carolina and Ohio shows that there is no any consistent preference for their physicians’ attire18 the possible difference might be cultural difference, national policy regarding physician attire and their study is in clinic level.

|

Table 4 Comparison of Four Commonly Preferred Female Physician Attires on Surgical Patients Perception at Addis Ababa Burns, Emergency, and Trauma Hospital, Ethiopia 2021 (N=366) |

The patients’ preference for formal physician attire in male surgeons’ confidence, willingness to discuss confidential information, and safeties of the surgeon to do the procedure were 76.2%, 75.7%, and 70.5% respectively, while scrub physician attire choice of patients on the caring ability of the surgeon, confidence on the surgeon, and willingness if he is his/her surgeon were 65%, 64.2%, and 58.5% respectively, which is in line with study findings3,11,14 but in contradict with these studies,3,18 the difference might be explained with the sample size difference, educational status and norms of patients. Other studies showed that the majority of patients (76%) preferred physicians wearing professional attire with a white coat rather than casual attire or business outfit,3,12,22 which is in line with our findings supported with a survey done of patients in a general medicine/endocrinology clinic in an Irish tertiary care center also found that white coats were preferred over other types of clothing.23

The male physician’s attire Formal vs scrub was significant in confidence (P=0.013) and discussion confidential information with doctors (P=0.013) but comparisons with formal attire vs business attire, formal attire vs casual attire, surgical scrub vs casual, and surgical scrub vs business attire were statistically significant with a p-value of p<0.001 in the confidence of surgical patients on surgeons, smartness, the surgical skill of the surgeon, and trustworthiness on the surgeon, but no statistically significance in business vs casual in among respondents as shown in (Table 3), which is supported with previous studies.4,24

For male surgeons, participants (81.7%) put formal attire as their first choice based on physician skill, and 14.4% preferred scrubs as their first choice, and for female surgeons, participants (74%) put formal attire as their first choice based on physicians’ skill and 22.4% of the participants put scrubs as their first choice. This finding is similar to other study findings.7,8,15

This is the first study in Ethiopia about the influence of physicians’ attire on surgical patients’ perception, so it may motivate others to do more research on this topic. It has also limitations including the models used in this research are young and the response may be different if the models were old. This study is mono-centric and relatively small sample size, so it is difficult to infer for the general population.

Conclusion

Physician attire is one of the important factors that inspire surgical patient confidence smartness, surgical skill, discussion on confidential information, and caring ability in physicians. In this study, formal attire and surgical scrub were the most appropriate preferred physicians outfits.

Acknowledgments

Firstly we would like to say thanks to St. Paul Millennium Medical College, for giving ethical clearance and, St. Paul specialized hospital for its positive response in data collection.

Secondly we highly gratitude all physicians who are volunteer to give their photos for the study, and also thank the data collectors and supervisors, and Orthopedics and Traumatology department staff.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research authorship/or publication of this article.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this work.

References

1. O’donnell VR, Chinelatto LA, Rodrigues C, Hojaij FC. A brief history of medical uniforms: from ancient history to the COVID-19 time. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020;47. doi:10.1590/0100-6991e-20202597

2. Brandt LJ. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1277–1281. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277

3. Al-Ghobain MO, Al-Drees TM, Alarifi MS, Al-Marzoug HM, Al-Humaid WA, Asiry AM. Patients’ preferences for physicians’ attire in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(7):763–767.

4. Jennings JD, Pinninti A, Kakalecik J, Ramsey FV, Haydel C. Orthopaedic physician attire influences patient perceptions in an urban inpatient setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(9):2048–2058. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000000822

5. Singh R, Kaur A, Nandi J. Looks do matter: patients’ perspective. Int J Health Clin Res. 2020;3(12):13–17.

6. Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, Crossley M. Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med. 2009;9(6):519. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.9-6-519

7. Varnado-Sullivan P, Larzelere M, Solek K, et al. The impact of physician demographic characteristics on perceptions of their attire. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):737–741. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.650493

8. Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1447-056X-13-2

9. Fadillah R, Syakurah RA, Rasyid RSP. Development of doctors attire according to patients preferences. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2020;11(3):1–5.

10. Lands VW, Malige A, Nwachuku CO, Matullo KS. The effect of an orthopedic hand surgeon’s attire on patient confidence and trust. HAND. 2019;14(5):675–683. doi:10.1177/1558944717750918

11. Al Amry KM, Al Farrah M, Ur Rahman S, Abdulmajeed I. Patient perceptions and preferences of physicians’ attire in Saudi primary healthcare setting. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(6):326–330. doi:10.1080/20009666.2018.1551026

12. Aldrees T, Alsuhaibani R, Alqaryan S, et al. Physicians’ attire: parents preferences in a tertiary hospital. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(4):435. doi:10.15537/smj.2017.4.15853

13. Alzahrani HM, Mahfouz AA, Farag S, et al. Patients’ perceptions and preferences for physicians’ attire in hospitals in south western Saudi Arabia. J Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2020;9(6):3119. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_166_20

14. Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):204–210. doi:10.12788/jhm.3350

15. Yamada Y, Takahashi O, Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Fukui T. Patients’ preferences for doctors’ attire in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49(15):1521–1526. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3572

16. de Souza-constantino AM, ACdCF C, Capelloza Filho L, Marta SN, de Almeida-pedrin RR. Patients’ preferences regarding age, sex, and attire of orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial. 2018;154(6):829–834. e821. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.02.013

17. Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, Van Asch K, Schoenmakers B. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Prim Health Care. 2013;3(3):1–9.

18. Hueston WJ, Carek SM. Patients’ preference for physician attire. Fam Med. 2011;43(9):643–647.

19. Landry M, Dornelles AC, Hayek G, Deichmann RE. Patient preferences for doctor attire: the white coat’s place in the medical profession. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):334–342.

20. Chung H, Lee H, Chang D-S, et al. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient–doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(3):387–391. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.017

21. Sotgiu G, Nieddu P, Mameli L, et al. Evidence for preferences of Italian patients for physician attire. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:361. doi:10.2147/PPA.S29587

22. Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, Kilpatrick AO. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118(11):1279–1286. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.026

23. Gallagher J, Stack J, Barragry J. Dress and address: patient preferences regarding doctor’s style of dress and patient interaction. Ir Med J. 2008;101(7):211–213.

24. Edwards RD, Saladyga AT, Schriver JP, Davis KG. Patient attitudes to surgeons’ attire in an outpatient clinic setting: substance over style. Am J Surg. 2012;204(5):663–665. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.001

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.