Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 14

Seeing the Elephant: A Systematic Scoping Review and Comparison of Patient-Centeredness Conceptualizations from Three Seminal Perspectives

Authors Olson AW , Stratton TP, Isetts BJ, Vaidyanathan R, Van Hooser JC, Schommer JC

Received 30 December 2020

Accepted for publication 19 March 2021

Published 29 April 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 973—986

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S299765

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Anthony W Olson, 1, 2 Timothy P Stratton, 2 Brian J Isetts, 3 Rajiv Vaidyanathan, 4 Jared C Van Hooser, 2 Jon C Schommer 3

1Research Division, Essentia Institute of Rural Health, Duluth, MN, USA; 2Department of Pharmacy Practice and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Minnesota – College of Pharmacy, Duluth, MN, USA; 3Department of Pharmaceutical Care and Health Systems, University of Minnesota – College of Pharmacy, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 4Department of Marketing, University of Minnesota Duluth – Labovitz School of Business and Economics, Duluth, MN, USA

Correspondence: Anthony W Olson 502 E 2nd Street, Duluth, MN, 55805, USA

Tel +1 218 786 1754

Fax +1 218 786 8159

Email [email protected]

Abstract: “Patient-Centeredness” (PC) is a theoretical construct made up of a diverse constellation of distinct concepts, processes, practices, and outcomes that have been developed, arranged, and prioritized heterogeneously by different communities of professional healthcare practice, research, and policy. It is bound together by a common ethos that puts the holistic individual at the functional and symbolic center of their care, a quality deemed essential for chronic disease management and health promotion. Several important contributions to the PC research space have adeptly integrated seminal PC conceptualizations to improve conceptual clarity, measurement, implementation, and evaluation in research and practice. This systematic scoping review builds on that work, but with a purpose to explicitly identify, compare, and contrast the seminal PC conceptualizations arising from the different healthcare professional groups. The rationale for this work is that a deeper examination of the underlying development and corresponding assumptions from each respective conceptualization will lead to a more informed understanding of and meaningful contributions to PC research and practice, especially for healthcare professional groups newer to the topic area like pharmacy. The literature search identified four seminal conceptualizations from the healthcare professions of Medicine, Nursing, and Health Policy. A compositional comparison across the seminal conceptualizations revealed a shared ethos but also six distinguishing features: (1) organizational structure; (2) predominant level of care; (3) methodological approach; (4) care setting origin; (5) outcomes of interest; and (6) language. The findings illuminate PC’s stable theoretical foundations and distinctive nuances needed to appropriately understand, apply, and evaluate the construct’s operationalization in contemporary healthcare research and practice. These considerations hold important implications for future research into the fundamental aims of healthcare, how it should look when practiced, and what should reasonably be required of it.

Keywords: patient-centeredness, medicine, nursing, health policy, pharmacy, systematic scoping review

Corrigendum for this paper has been published

Introduction

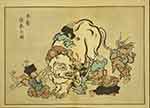

There is an Eastern parable about a group of blind monks who come across a creature they are unfamiliar with, which is represented by Japanese artist Hanabusa Itchō in Figure 1.1 The story goes that one of the monks touches the creature’s tusks and proclaims to the others that the animal is “sharp,” while another grabs the tail and disagrees, announcing that the animal is “smooth.” Each monk goes on to accurately describe their seemingly incompatible experience to the others, leading to an argument. It escapes the monks that the elephant is too big and complex for them to understand from any one of their single, independent perspectives.

|

Figure 1 Blind monks examining an elephant (Hanabusa Itchō, 1652–1724). Notes: Reproduced from Itcho H. [Blind monks examining an elephant]. In: The Floating World of Ukiyo-e: Shadows, Dreams, and Substance. Abrams in association with the Library of Congress; 2001:96. 1 |

The allegory may hold insights for approaching the construct of “Patient-Centeredness” (PC), a diverse constellation of distinct concepts, processes, practices, and outcomes reflecting development from traditionally siloed healthcare practice, research, and policy communities but bound together by a common ethos that puts the holistic individual at the functional and symbolic center of their care.2–8

What PC “is” and what it is thought to achieve can be dependent on factors such as the nature of a disease (eg, cancer or diabetes), care population (eg, pediatric or geriatric), setting (eg, outpatient or inpatient), expertise of the caregiver (eg, Medicine or Nursing), service (eg, self-management support or care environment aesthetics and amenities), system (eg, Bismarck or Beveridge), as well as elements beyond a traditional health focus including employment, mobility, housing, and even personal identity.9–11 The broad versatility and applicability of PC may justifiably explain differences in understandings, measurements (eg, patient-reported, expert-observed), practices (eg, “shared decision making,” “self-management”), and evaluations (eg, clinical outcomes, non-clinical outcomes) of the construct across the wide diversity of stakeholders who hold different assumptions, interests, and goals. This cacophony of influencing variables likely explains mixed findings in the literature regarding the effectiveness of interventions informed by PC.9

Consider a 67-year-old patient who arrives at an Emergency Department (ED) by ambulance with elevated blood pressure, shortness of breath, and chest pain. The ED staff work as a team to evaluate and room the patient efficiently, while maximizing the patient’s comfort, emotional support, and informational updates to the best of their ability in a busy and crowded ED with little privacy. The initial results from the patient’s blood work and electrocardiogram are negative for myocardial infarction and the risk of a heart attack within the next few weeks is estimated to be low. The attending ED physician collects all relevant information from the team and comes to concordance with the patient using a shared decision-making process to forgo additional testing or hospitalization in favor of a discharge with a primary care provider appointment in a few days' time. The ED physician also sends the patient home with nitroglycerin and lisinopril after providing instructions on how to take them. Three days later, the patient is dropped off at their primary care provider’s clinic by their spouse, who goes to run an errand rather than find parking in the busy urban area. At the visit, the patient and primary care provider collaboratively discuss the patient’s clinical (eg, blood pressure), emotional (eg, PHQ-9), and social (eg, housing, food, financial security) health as well as the patient’s goal to be on as few medications as possible. The 20-minute encounter leads to a new diagnosis of anxiety, prescriptions of venlafaxine and clonazepam to treat the new diagnosis to be delivered via mail-order for convenience, and discontinuation of the antihypertensive medication as the patient’s blood pressure was consistently normal. The patient returns home with their spouse, commenting on the strong bond they feel with their PCP. Over the next week the patient takes their medications as prescribed, but starts to experience dizziness and has trouble remembering things, which irritates their spouse. For these reasons, the patient decides to stop taking the medication and returns to the ED a few weeks later after experiencing shortness of breath and chest pain again.

The scenario described above contains several elements of PC (eg, shared decision-making, care coordination and integration, biopsychosocial perspective) that overlap multiple seminal conceptualizations for the construct from different health professional groups, while also highlighting different areas of emphasis and alternative interpretations about what went wrong or what could be improved among them. For example, a conceptualization from one professional group would emphasize changes to the care environments (eg, ED privacy, valet for the urban clinic) to improve the patient’s care experience, while another would be more concerned with preventing the re-hospitalization through better facilitation of the spouse’s active involvement in care to the patient’s desired level. Still another conceptualization would underscore the need to better exploring the patient’s unique illness experience to identify important contributors to the anxiety that lead to more tailored and effective interventions.

The case above exemplifies both the overlap and heterogeneity of the PC literature, which is understandable but may not be benign. There is a risk that PC becomes a buzzword or platitude with a sufficiently muddled meaning to enable specious or co-opted operationalizations contrary to its core ethos.5,9,12,13 This possibility is exacerbated by the multi-professional and integrated nature of modern healthcare practice, research, policy, and payment where diverse teams support patients with multiple co-morbidities and varying levels of resources and support. Furthermore, several professional constituent groups of the healthcare team such as pharmacists have yet to rigorously examine PC intraprofessionally, let alone to constructively connect their respective perspectives to the broader literature.9,14 While some may see these prospective contributions as counterproductive to the PC research space by adding another “blind monk” to the “argument,” these added insights also represent an opportunity to advance the understanding of the elephant’s (ie, PC’s) true nature. For instance, in this patient case, a provider or patient relationship with a pharmacist may have reasonably led to the selection of sertraline and lorazepam for anxiety medications rather than venlafaxine and clonazepam given the former pair’s lower side effect profile in persons 65 years or older, thus reducing the likelihood that the patient stops taking their medications and is re-hospitalized.15

Care scenarios such as these demonstrate the need to cross-link conceptualizations of PC from different segments of the literature to optimally preserve and progress the cohesion, development, implementation, and evaluation of the construct.4,5,16–18 Several important contributions to this effort by Scholl et al,5,19,20 Pelzang,21 Kitson et al,4 the Health Policy Partnership9 and many others have advanced this cause by consolidating common elements of PC to identify unifying themes within the construct.

This systematic scoping review builds on that work, but with an objective to explicitly identify, compare, and contrast the seminal PC conceptualizations arising from the different healthcare professional groups. The rationale for this work is that a deeper examination of the underlying development and corresponding assumptions from each respective conceptualization will lead to a more informed understanding of and meaningful contributions to PC research and practice, especially for healthcare professional groups newer to the topic area like pharmacy. This aim was also part of a broader project attempting to conceptually extend and seminally connect the PC construct in the pharmacist practice literature.22

Methods

Search Strategy, Protocols, and Results

The literature search for this review used an electronic database-driven protocol to identify the seminal conceptualizations of the PC construct in healthcare practice. Eligible sources included articles in peer-reviewed journal articles found in the following nine databases: CINAHL, Digital Dissertations, Health & Psychosocial Instruments, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Sociological Abstracts, Academic Search Premier, Cochrane, and EMBASE. These nine databases were selected from the 74 health science databases because their descriptions aligned with this review’s purpose and represented a diverse set of disciplinary, theoretical, and methodological approaches. Terms searched for within the titles of articles indexed in these databases included Patient-Centered* OR Patient-Centred*; Client-Centered* OR Client-Centred*; Person-Centered* OR Person-Centred*; Patient-focused*; Patient empowerment; Patient engagement; Patient self-management; and Shared decision making.

The search was limited to publication titles rather than just keywords to reduce results containing peripheral use of PC terminology lacking awareness and understanding of the construct’s canonical interpretations in the seminal literature. The multiple spellings of “Centered” in the first three bullet points account for regional spelling differences present throughout the PC literature. North American sources generally use “Centered,” while “Centred” is more common among European publications. Going forward in this review, the North American spelling variation will be used unless directly quoting an author or referencing a model where the European spelling is utilized.

For feasibility, a search result was removed from consideration if it: [a] was a conference abstract, book review, magazine article, or short commentary; [b] was written in a non-English language; [c] used PC terminology lacking a clear connection, granularity, or depth in relation to the construct’s overarching ethos (eg, operational measures disconnected from theory); or [d] involved PC conceptualizations peripheral to a healthcare professional group focus (eg, disease state, care setting).

Table 1 and Figure 2 summarize the search results by database and filter settings for each respective database. Abstracts of the search results were screened for appropriateness and quality by the lead author to produce a reading list. Publications selected for the reading list were more likely to come from authors with several contributions over time and were more frequently cited in peer-reviewed journals than publications excluded from the reading list. Please note that well-developed PC conceptualizations originating from research communities that took longer to adopt search protocol terminology, more prominently frame PC around philosophical principles or concrete care practices and measures rather than a theoretical conceptualization, focus on integrating pre-existing seminal conceptualizations, and are relatively smaller in size may be underrepresented in the results. Sources included for reading and analysis were also identified using alternative methods based on suggestions from PC content experts’ suggestions and more frequently cited references in the literature. All sources selected for reading were imported using Mendeley (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and duplicates were merged.23

|

Table 1 Search Protocol Details and Results Summary |

|

Figure 2 Search protocol details and results. Notes: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 6(7): e1000097. Copyright: © 2009 Moher et al. Creative Commons Attribution License.76 |

The search process yielded 1385 non-duplicated references, of which 1298 references came from the electronic database search. The remaining 87 references were identified from recommendations provided by PC content experts or frequent references throughout the PC literature (ie, an iterative snowballing technique). Screening of these initial sources was conducted using the aforementioned criteria to select 257 publications for reading and analysis. A theoretical conceptualization of the PC construct was classified as “seminal” if it was mentioned within at least 30 references from the search results.

Results

The Origins of Patient-Centeredness

The first contemporary antecedent of PC was Rogers’ “client-centered therapy” from the psychology literature in 1951.24 Rogers stated that individuals were capable of self-remedying their problems by employing their own resources assuming they are provided with necessary supportive conditions.25 This idea expanded the purview of medical treatment to a person’s subjective and holistic experience, which included the “therapeutic alliance” between a patient and physician.

An additional antecedent of PC developed by psychoanalysts Michael and Enid Balint in the 1960s was “Patient-Centered Medicine,” defined as “the patient’s total experience of illness”26,27 and “understanding the patient as a unique human being,”28 respectively. Other notable contributors to the PC literature in the 1970s were Neuman and Young, who encouraged a “total-person approach to patient problems” in Nursing,29 as well as Byrne and Long’s “Patient-Centered Medical Practice,” which asserted that physicians should guide their encounters with the knowledge and experience of patients.30 The psychiatrist George Engel also introduced the “biopsychosocial perspective” concept in 1977, which directly challenged the prevailing view at the time that health and human development could be sufficiently explained by biological and psychological factors alone. Engel argued that socio-environmental elements were also necessary in this explanation.31,32

Almost a decade later, British-Canadian physician Ian McWhinney adroitly advocated for the medical profession’s adoption of the “biopsychosocial perspective” by citing philosopher Thomas Kuhn’s idea that scientific progression periodically undergoes dramatic “paradigm shifts” whereby accepted views about the nature of things should be abandoned when an alternative model better accounts for anomalies.32,33 McWhinney pointed out that the disease-oriented paradigm of medical practice contained multiple anomalies (eg, patients experiencing illness without a diagnosable disease, the distinction between treatment and healing) that were better explained by a person-oriented paradigm incorporating the “biopsychosocial perspective.”29 He and his team described this approach as attempting to:

Enter the patient’s world, to see the illness through the patient’s eyes … and [facilitate] openness … to understand each patient’s expectations, feelings, and fears. Every patient who seeks help has some expectations of the visit, not necessarily made explicit.34

McWhinney’s contributions propagated the spread of PC research across healthcare professional groups, especially Medicine, Nursing, and Health Policy.4

Conceptualizations of Patient-Centeredness in Medicine

Canadian primary care physician Moira Stewart, a protégé of McWhinney, is arguably one of the most influential contributors to PC research from Medicine.35 Stewart’s desire to improve the “physician–patient relationship” (ie, a two-person medicine focus) in the primary care setting informed her interpretation of the PC construct. She pinpointed six aspects of “patient-centered communication” desired by persons when interacting with their physicians: [1] explore the patient's experience and expectations of disease and illness (ie, feelings about being ill, impact on daily function, expectations of what to do); [2] seek an integrated understanding of the patient's world (ie, a whole person approach including emotional needs and life issues); [3] find common ground on what the problem is and mutually agree on management; [4] enhance disease prevention and health promotion; [5] enhance the continuing relationship between the patient and the doctor; and [6] be realistic about what can be achieved.36–40

Stewart contends that PC requires a willingness by physicians to immerse themselves in a person’s overall wellbeing related to the psychosocial context, rather than focus solely on biomedical problems. Therefore, care evaluation should incorporate both clinical and non-clinical outcomes. Notable findings from studies referencing Stewart’s conceptualization suggest that patient perceptions of the presence of PC in their care are more predictive of positive outcomes than the presence of observable behaviors judged to be patient-centered by physicians (eg, provider-oriented activity checklists, asking open-ended questions, prolonged silence to encourage patient-led conversation).35,39–44 This contributed to Stewart’s conception of PC as a unitary construct, not divisible into stand-alone surrogates for meaningful measurement or evaluation, while still acknowledging that practice tools like checklists could be useful or informative if recognized as imperfect surrogates.

The monolithic nature of the PC construct was challenged by some of Stewart’s colleagues, including Mead and Bower from the United Kingdom, who aimed to capture the divisible components of the PC construct beyond the primary care context, using a comprehensive review approach generalizable to all of Medicine.45 The pair identified and described five overlapping but separable non-ordinal components: [1] Biopsychosocial Perspective; [2] Patient as a Unique Person; [3] Sharing Power and Responsibility; [4] Therapeutic Alliance; and [5] Doctor-as-Person. Later contributions by Hudon et al found that four of Mead and Bower’s five components match well with Stewart’s conceptualization despite differences in terminology, as represented in Figure 3.

35Conceptualization of Patient-Centeredness in Health Policy

The seminal conceptualization of PC from Health Policy is the product of Harvard Medical School affiliates in the United States that eventually became the Picker Institute. The Picker Institute conceptualized the following eight non-ordinal “Picker Principles” for PC: [1] Respect for patient preferences, values, and expressed needs; [2] Coordination and integration of care services; [3] Information, education, and communication; [4] Physical comfort; [5] Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; [6] Involvement of family and close others; [7] Continuity and transition from hospital to home; and [8] Access to care.46 These principles have since been adopted by the United States Institute of Medicine (IoM) in a 2001 report naming patient-centered care as an essential element for quality improvement in the 21st century US healthcare system.47

The development of the first seven Picker Principles consisted of a multi-step, systematic process of data collection and analysis of focus groups, interviews (phone and in-person), and questionnaires from recently discharged patients, their families, and respective inpatient care teams. The primary objective was to understand “what matters” to patients and their families as well as what impacts them in their interaction with providers, health systems, and institutions. The eighth principle was added later to expand the conceptualization’s relevance to outpatient care settings.

The Picker Principles have guided the development of healthcare innovations like the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Patient-Centered Medical Home” care model and “Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems” (CAHPS) patient experience outcome measures, the latter of which is used by Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Value-based Purchasing programs.48

Conceptualization of Patient-Centeredness in Nursing

The third seminal stream of PC research identified in this review combined works from McCormack on “authentic consciousness” (ie, autonomy)49 and McCance on care in Nursing50 to create the Person-centered Nursing Framework.51 The most recent iteration of this model was renamed the Person-centred Practice Framework (PCPF) and is represented in Figure 4.9,52 The PCPF contains 25 concepts layered into five sequentially-ordered categories that must be fulfilled in a stepwise fashion to facilitate care service organization and delivery that center on the individualized needs of each patient. The Framework begins with the “Macro Context” layer and concludes at a “Person-Centred Outcomes,” a terminus that purposefully excludes clinical outcomes (eg, hemoglobin A1c, lipid profiles, etc.). This is because the PCPF was developed to be a comprehensive approach guiding how nurses should fit into the patient’s life as a whole, and not an algorithmic instrument for ranking or performing specific activities to meet health system or even patient desires. From this perspective, PC is a moral imperative and valuable end in and of itself regardless of the clinical outcomes or savings it produces.53

|

Figure 4 McCormack and McCance’s “The Person-centred Practice Framework re-presented.” Notes: Republished with permission of John Wiley & Sons - Books from McCormack B, McCance T, Klopper H. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.52 |

The PCPF has informed several quantitative and qualitative measures developed by an international research and practice collaborative of academic clinical institutions known as The International Community of Practice for Person-centred Practice.54–57 These tools produce the empirical evidence linking the PCPF’s structures and processes with its Person-Centred Outcomes, especially for inpatient settings like intensive care units,58 hospitals,59–61 and nursing homes.62 The PCPF has also been extended to the implementation and evaluation of initiatives in professional education curriculums,63–65 leadership development,62,66 care delivery training programs,61,67–69 and cultural change projects.70

Comparisons of Patient-Centeredness Between Medicine, Health Policy, and Nursing

A compositional comparison of PC conceptualizations from Medicine, Nursing, and Health Policy reveals a shared ethos that binds the traditions together (ie, placing the individual person at the functional center of their care), which is more robust than the characteristics that differentiate them from one another. This is evidenced first and foremost by the degree of overlap across the conceptualizations from each respective tradition, as seen in Figure 5. Vertical spatial alignment in the concept map represents concepts belonging to the same tradition (eg, Therapeutic Alliance, Biopsychosocial Perspective, and Provider-as-Person all originate from Medicine), while horizontal spatial alignment signifies commonalities in conceptual definitions and applications (eg, Therapeutic Alliance from Medicine and Authentic Engagement from Nursing capture similar ideas).

|

Figure 5 Analogous concept map of seminal PC concept alignment across Medicine, Nursing, and Health Policy patient-centeredness conceptualizations.37,45,46,52 Notes: *McCormack and McCance’s person-centred outcomes; cells with X signify that no concept from respective seminal traditions existed in the specified area. |

Assessing the conceptual gaps found in Figure 5 (ie, cells with X) also reveals distinguishing features among the conceptualizations from each respective condition, which are depicted in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Six Distinguishing Features of Patient-Centeredness Conceptualizations in Medicine, Nursing, and Health Policy |

Organizational Structure

The first distinguishing feature among the respective conceptualizations is the organizational structure. Both Medicine and Health Policy utilize a “process-oriented” organizational structure, characterized by non-ordinal principles that nominally inform their understanding of a patient’s perspective to determine the essential therapeutic considerations of their care.21 Alternatively, Nursing uses a “systems-oriented” organizational structure sequentially arranged and focused on adopting the patient's beliefs and values to adjust the healthcare environment to meet their unique needs.4,21 The different organizational structures may reflect the distinctive roles and duties inherent to the professionals from each respective PC tradition. For example, physicians and health policy-oriented stakeholders may find more value in using process-oriented principles to guide medical decision-making or strategic priorities, while traditional inpatient nursing focuses on orienting and organizing the care activities produced by systems around each person’s beliefs, values, and needs.

Predominant Level of Care

A second distinguishing feature among the traditions is the predominant levels at which the aspects of care occur, namely the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. The micro-level of PC refers to care that takes place within and adjacent to the patient–provider encounter, while the meso-level of PC encompasses the environmental conditions within and adjacent to healthcare institutions organizing care. The macro-level represents upstream factors like legislation, accreditation, payment, and workforce dynamics related to PC. Interestingly, Figure 5 is roughly arranged in a continuum with the micro-level reflected by concepts closer to the top, the macro-level at the bottom, and the meso-level sandwiched in-between. The PC conceptualizations of Medicine and Nursing understandably manifest more neatly at the micro- and meso-levels of care, reflected by the concentrated conceptual presence of these traditions in the top half of the concept map. This general area also shows a conceptual gap in the Health Policy tradition as it relates to the individual attributes of the care provider (eg, Provider as Person, Professional Competency). It is unclear whether this omission results from an underlying premise that providers with similar qualifications are seen as equivalent and interchangeable (ie, payment, licensing, and accreditation bodies) in providing services or is simply an artifact of the methodological approach taken to build conceptualization. Alternatively, the bottom half of Figure 5 consists of concepts most relevant to the meso- and macro-levels originating from Nursing and Health Policy, with no representation from Medicine at all in the concepts existing outside of the patient care encounter. Also notable is how well the ordinal sequence of concepts found in Nursing’s PCPF is preserved in the concept map, suggesting how the Framework’s system-oriented organizational structure is arranged with levels of care in mind. For example, the Framework begins at the “Macro Context” and moves inwards through layers that get progressively closer to direct patient care (ie, micro-level). Interestingly, the concepts found in the terminal “Person-Centred Outcomes” layer are fairly evenly distributed from the top to bottom in Figure 5, suggesting that aspects from each level of care are assessed in determining PC.

Methodological Approach and Care Setting of Origin

The third and fourth distinguishing features among the seminal PC traditions are the methodological approach and care setting origin. These features represent how and where patient data informing the conceptualizations were acquired and analyzed, respectively. Both Stewart’s and Mead and Bower’s conceptualizations of PC in Medicine were developed using a deductive methodological approach that applied theoretical literature to inform how medical encounters could be observed.39,45 In contrast, the Picker Principles from Health Policy were produced from an inductive process drawn from interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires with participants with some consideration of theoretical literature.46 The methodology and care setting of origin for McCormack and McCance’s work is less explicit than the other two traditions. However, the PCPF’s grounding in the philosophical literature and goodness of fit with nursing practice in hospital settings point to a deductive approach originating from an inpatient setting. The most recent iterations and uses of conceptualizations from all three traditions have been adapted for or applied to both outpatient and inpatient settings, but understanding their distinctive development processes may shed light on their strengths, limitations, and general relevance in different contexts.

Outcomes of Interest

A fifth distinguishing feature is the types of outcomes of interest associated with the conceptualizations from each seminal tradition. The PCPF from Nursing incorporates only subjective, patient-reported outcomes, which are less pronounced in the conceptualizations from Medicine and Health Policy that also include objective to clinical indicators of “healthiness” like hemoglobin A1c, and lipid profiles.39,45,46,51 This raises an important question about what can and should be achieved by care as it pertains to the nature of a disease, the service being provided, and the expertise of the caregiver, but also aspects beyond a traditional healthcare focus like employment, mobility, housing, and even personal identity.9–11 A major international review of the PC literature found that the concerns of the patient are underrepresented in healthcare study endpoints in favor of the clinical outcomes and economic considerations around which modern healthcare services and payment are organized (ie, medical records containing discrete biomedical categories for tracking services and payment).71 The result is inherent tensions in how healthcare providers practice and are evaluated by stakeholders with different interests. That said, non-clinical outcomes like patient satisfaction and patient experience have recently grown in importance, as demonstrated by their use in some healthcare payment structures (eg, CMS Value-based purchasing using “Hospital CAHPS” scores) as well as some healthcare institutions publicly reporting this information.

Language

A final distinguishing feature is differences in the language and terminology used among the respective PC conceptualizations from these seminal traditions of PC. The Nursing tradition differs from Medicine and Health Policy by intentionally substituting “Person” for “Patient” in the “P” of “PC.” Proponents for the “Person-Centeredness” language provide several reasons for their preference despite both terms sharing a well-recognized commonality in humanistic psychology origins, a “Biopsychosocial Perspective,” and general philosophies. First, “Person” prioritizes the identity of a whole individual’s being for interpreting the health problem, encounter, and patient–provider relationships better than does “Patient,” which frames the individual as a recipient of care in a health system or specialty area with its own goals and values for a disease.13 Additionally, the idea of a potential for co-equal partnership between the individual and caregiver is better implied by using “Person” rather than “Patient,” which carries connotations of parentalism where the provider holds the expertise and power in all health-related matters. Still, other members of the PC research community see only a semantic difference because both “Person”- and “Patient”-Centered models emphasize a holistic, biopsychosocial approach with the potential for patients and providers to be co-equal partners.72 Therefore, there is no real substantive difference beyond an indication of one’s country of origin given that “Person-Centered” is used more frequently in European and outpatient settings while “Patient-Centered” is found primarily in North American and inpatient settings.4,9,18,25,73

Discussion

The findings of this review affirm the stable theoretical foundations of PC among healthcare professional groups, while illuminating distinctive features and corresponding assumptions useful for appropriate understanding, application, and evaluation of the construct’s operationalization in diverse contexts. The compositional congruence across the seminal conceptualizations suggests that efforts to consolidate alternative interpretations of the construct are not unreasonable and can advance the field by facilitating evidence accumulation across differing contexts, and facilitate general best practices, while also protecting against semantic bleaching (ie, loss or reduction of the explicit meaning of the term).74

At the same time, the pursuit of a more global and standardized meaning of PC must be balanced against or account for the value added by recognizing the distinguishing characteristics of its seminal components, particularly for fields that are less established and can bring new insights that advance understanding. Research from these less established fields also provides an opportunity to bring fresh scrutiny to hidden assumptions underlying existing PC conceptualizations that have as yet gone unchallenged. The differences also provide a foothold for relatively newer entrants in the general PC research space, such as pharmacy, to identify how they learn from, contribute to, and fit with the overarching picture. For example, Mead and Bower’s conceptualization from Medicine may be more valuable for pharmacists seeking to optimize the quality, value, and impact of their direct patient care encounters (ie, process-oriented, micro-level), while McCormack and McCance’s PCPF may help a dentist better integrate with other members of a person’s healthcare team (ie, system-oriented, meso-level). Additionally, both instances represent opportunities to correct methodological shortcomings (ie, suboptimal assumptions in deductive approaches; incomplete or false reasoning in inductive approaches), hidden biases tied to care setting of origin, and the most relevant outcomes in novel contexts. Finally, highlighting the distinguishing characteristics can improve awareness of the multifaceted nature of PC and bring to the forefront important conversations about the fundamental aims of healthcare (eg, social equity, financial cost-effectiveness, improved quality of life), how it should look when practiced (eg, activities, systems, policies), and what should reasonably be required of it (eg, acceptable levels of disease prevention, holistic wellbeing, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, patient experience) in both universal and niche contexts.9

Addressing these important questions requires thoughtful scrutiny of the processes and populations (ie, underlying values, assumptions, aptitudes, shortcomings, roles, and needs) that produce and are affected by the answers.

Limitations and Future Research

This review was limited to sources written in English and may not have identified important work written in other languages. It is also important to note that PC derives primarily from Western traditions of philosophy, values, and healthcare approaches (eg, individual autonomy, privacy, deductive diagnoses, etc.).75 The source selection process for reading and analysis may have resulted in less representation of literature from research communities that took longer to adopt search protocol terminology, frame PC around philosophical principles or concrete care practices and measures rather than a theoretical conceptualization, focus on integrating pre-existing seminal conceptualizations, and are relatively smaller in size, which may thus be underrepresented in the results. Future research should better account for the important and developing work from these spaces, especially given the multi-professional nature of contemporary team-based healthcare. Finally, the methodological and analytical rigor of sources was not considered in the source selection process, particularly given the theoretical focus of the review as opposed to operational measurement.

Conclusion

There is seemingly universal consensus surrounding the importance, relevance, and potential of PC to inform high value care that contrasts starkly with disagreements over its meaning in different communities. Efforts to produce a universal definition face a seemingly paradoxical challenge to standardize a term that emphasizes individualization, perhaps much like blind monks struggling to understand how an elephant can be both “sharp” and “smooth.” This integrative review intends to help researchers and practitioners work to see the elephant, rather than just the tusk or leg. Advancement in revealing a more complete understanding of PC requires openness to perspectives from different vantage points and a conceptual foothold for building a shared understanding among stakeholders. In this review, compositional comparisons across seminal PC conceptualizations revealed a shared ethos, but also six distinguishing features: organizational structure; predominant level of care; methodological approach; care setting origin; outcomes of interest; and language. The findings illuminate PC’s stable theoretical foundations and distinctive nuances that may represent a multi-disciplinary baseline for consideration of the shape and meaning of the PC ethos, while still allowing for flexibility across diverse patient care contexts in contemporary healthcare research and practice.

Acknowledgment

Funding was provided by the University of Minnesota’s Peters Endowment for Pharmacy Practice and Innovation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Itcho H. [Blind monks examining an elephant]. In: The Floating World of Ukiyo-e: Shadows, Dreams, and Substance. Abrams in association with the Library of Congress; 2001:96. Available from: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004666374/.

2. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient–physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001

3. Olsson L-E, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I. Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials - a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(3–4):456–465. doi:10.1111/jocn.12039

4. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x

5. Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness– a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107828. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107828

6. Collins A. Measuring what really matters towards a coherent measurement system to support person-centred care. Health Found. 2014;20.

7. de Silva D. Helping measure person-centred care. Health Found. 2014:80.

8. Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):197–206. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00194-5

9. Harding E, Wait S, Scrutton J. The state of play in person-centred care: a pragmatic review of how person-centred care is defined, applied, and measured featuring selected key contributors and case studies across the field. Health Policy Partnership. 2015:139.

10. Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. BMJ. 2015;350(feb1014):h181–h181. doi:10.1136/bmj.h181

11. Corcoran KJ, Jowsey T, Leeder SR. One size does not fit all: the different experiences of those with chronic heart failure, type 2 diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(1):19. doi:10.1071/AH11092

12. Hawkes N. Seeing things from the patients’ view: what will it take? BMJ. 2015;350:g7757. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7757

13. Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. Person-centered care-ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–251. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

14. Dowse R. Reflecting on patient-centred care in pharmacy through an illness narrative. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(4):551–554. doi:10.1007/s11096-015-0104-5

15. Beers criteria medication list. DCRI. Available from: https://dcri.org/beers-criteria-medication-list/.

16. Rathert C, Williams ES, McCaughey D, Ishqaidef G. Patient perceptions of patient-centred care: empirical test of a theoretical model. Health Expect. 2015;18(2):199–209. doi:10.1111/hex.12020

17. Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2

18. Edvardsson D, Innes A. Measuring person-centered care: a critical comparative review of published tools. Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):834–846. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq047

19. Zill JM, Scholl I, Härter M, Dirmaier J, Wu W-CH. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? - results of a web-based expert delphi survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141978

20. Zill JM, Scholl I, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Evaluation of dimensions and measurement scales in patient-centeredness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:345–351. doi:10.2147/PPA.S42759

21. Pelzang R. Time to learn: understanding patient-centred care. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(14):912–917. doi:10.12968/bjon.2010.19.14.49050

22. Olson AW. Patient-centeredness in pharmacist practice: filling a foundation for what counts to patients; 2020. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2445298748.

23. Elsevier. Mendeley - reference management software. 2020.

24. Rogers CR, Carl R. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory. Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

25. Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, Lefeve C, Pachoud B, Ville I. Person-centredness: conceptual and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(20–21):1555–1565. doi:10.1080/09638280701618661

26. Balint M. The doctor, his patient, and the illness. Lancet. 1955;265(6866):683–688. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(55)91061-8

27. Howie J, Heaney D, Maxwell M. Quality, core values and the general practice consultation: issues of definition, measurement and delivery. Fam Pract. 2004;21(4):458–468. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmh419

28. Balint E. The possibilities of patient-centered medicine. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1969;17(82):269–276.

29. Neuman BM, Young RJ. A model for teaching total person approach to patient problems. Nurs Res. 1972;21(3):264–269. doi:10.1097/00006199-197205000-00015

30. Byrne PS, Long BEL. Doctors Talking to Patients: A Study of the Verbal Behaviour of General Practitioners Consulting in Their Surgeries. H.M.S.O; 1976. Available from: https://books.google.com/books/about/Doctors_Talking_to_Patients.html?id=oY0LAQAAIAAJ.

31. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535–544. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.5.535

32. Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

33. Mcwhinney IR. Changing models: the impact of Kuhn’s theory on medicine. Fam Pract. 1984;1(1):3–8. doi:10.1093/fampra/1.1.3

34. Levenstein JH, Mccracken EC, Mcwhinney IR, et al. The patient-centred clinical method. 1. A model for the doctor-patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3(1):75–79. doi:10.1093/fampra/3.2.75

35. Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert MM, Poitras M-ER. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):155–164. doi:10.1370/afm.1226

36. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study on effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. Br Med J. 2001;323(7318):908–911. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908

37. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9):1423–1433.

38. Stewart M. Patient characteristics which are related to the doctor-patient interaction. Fam Pract. 1984;1(1):30–36. doi:10.1093/fampra/1.1.30

39. Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method.

40. Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):444–445. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444

41. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

42. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: Observational Study. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):468–472. doi:10.1136/BMJ.322.7284.468

43. Henbest RJ, Stewart M. Patient-centredness in the consultation. 2: does it really make a difference? Fam Pract. 1990;7(1):28–33. doi:10.1093/fampra/7.1.28

44. Haggerty J, Burge F, Lévesque J-F, et al. Operational definitions of attributes of primary health care: consensus among Canadian experts. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):336. doi:10.1370/AFM.682

45. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–1110. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8

46. Gerteis M. Picker/Commonwealth Program for Patient-Centered Care. Through the Patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. Jossey-Bass; 2002.

47. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press; 2001.

48. Shaller D. Patient-centered care: what does it take?; 2007. Available from: www.commonwealthfund.org.

49. McCormack B. A conceptual framework for person-centred practice with older people. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9(3):202–209. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00423.x

50. McCance TV. Caring in nursing practice: the development of a conceptual framework. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(2):101–116. doi:10.1891/rtnp.17.2.101.53174

51. McCormack B, McCance TV. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):472–479. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04042.x

52. McCormack B, McCance T, Klopper H. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice.

53. Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, Greene SM, Schaefer JK, Vonkorff M. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(supplement1):

54. McCance T, Telford L, Wilson J, MacLeod O, Dowd A. Identifying key performance indicators for nursing and midwifery care using a consensus approach. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7–8):1145–1154. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03820.x

55. McCormack B, Henderson E, Wilson V, Wright J. Making practice visible: the Workplace Culture Critical Analysis Tool (WCCAT). Pract Dev Health Care. 2009;8(1):28–43. doi:10.1002/pdh.273

56. Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B. The development and testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory– Staff (PCPI-S). Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(4):541–547. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzx066

57. McCormack B, McCarthy G, Wright J, Coffey A, Coffey A. Development and testing of the Context Assessment Index (CAI). Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(1):27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00130.x

58. Papathanassoglou EDE. Psychological support and outcomes for ICU patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2010;15(3):118–128. doi:10.1111/j.1478-5153.2009.00383.x

59. Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B. Exploring person-centred practice within acute hospital settings. Int Pract Dev J. 2015;5(Suppl):1–8. doi:10.19043/ipdj.5SP.011

60. Parlour R, Slater P, Mccormack B, Gallen A, Kavanagh P. The relationship between positive patient experience in acute hospitals and person-centred care. Int J Res Nurs. 2014;5(1):27–36. doi:10.3844/ijrnsp.2014.27.36

61. Mccance T, Gribben B, McCormack B, Laird EA. Promoting person-centred practice within acute care: the impact of culture and context on a facilitated practice development programme. Int Pract Dev J. 2013;3(1).

62. Lynch BM, McCance T, McCormack B, Brown D. The development of the person-centred situational leadership framework: revealing the being of person-centredness in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1–2):427–440. doi:10.1111/jocn.13949

63. Carson OM, Laird EA, Reid BB, Deeny PG, McGarvey HE. Enhancing teamwork using a creativity-focussed learning intervention for undergraduate nursing students - A Pilot Study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;30:20–26. doi:10.1016/J.NEPR.2018.02.008

64. Cook NF, McCance T, McCormack B, Barr O, Slater P. Perceived caring attributes and priorities of preregistration nursing students throughout a nursing curriculum underpinned by person-centredness. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(13–14):2847–2858. doi:10.1111/jocn.14341

65. Kuehn BM. Patient-centered care model demands better physician-patient communication. JAMA. 2012;307(5):441–442. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.46

66. Cardiff S, McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred leadership: a relational approach to leadership derived through action research. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(15–16):3056–3069. doi:10.1111/jocn.14492

67. Buckley C, McCormack B, Ryan A. Working in a storied way-narrative-based approaches to person-centred care and practice development in older adult residential care settings. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(5–6):e858–e872. doi:10.1111/jocn.14201

68. Laird EA, McCance T, McCormack B, Gribben B. Patients’ experiences of in-hospital care when nursing staff were engaged in a practice development programme to promote person-centredness: a Narrative Analysis Study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(9):1454–1462. doi:10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2015.05.002

69. van Lieshout F, Titchen A, McCormack B, McCance T. Compassion in facilitating the development of person-centred health care practice. J Compassionate Health Care. 2015;2(1):5. doi:10.1186/s40639-015-0014-3

70. McCormack B, Mccance T, Slater P, Mccormick J, Mcardle C, Dewing J. Person-centred outcomes and cultural change. In: International Practice Development in Nursing and Healthcare. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009:189–214. doi:10.1002/9781444319491.ch10

71. Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD010523. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2

72. Epstein RM. The science of patient-centered care. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):805–807.

73. Brookman C, Jakob L, Decicco J, Bender D. Client-Centred Care in the Canadian Home and Community Sector: A Review of Key Concepts. 2011. Available from: www.saintelizabeth.com.

74. Traugott E. Semantic change: bleaching, strengthening, narrowing, extension. In: Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics.

75. Tseui JJ. Eastern and western approaches to medicine. West J Med. 1978;128(6):551–557.

76. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.