Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Aesthetic Experience and the Ability to Integrate Beauty: The Mediating Effect of Spirituality

Authors Świątek AH , Szcześniak M , Borkowska H , Bojdo W, Myszak UZ

Received 16 June 2023

Accepted for publication 15 September 2023

Published 29 September 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4033—4041

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S423513

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Agata H Świątek, Małgorzata Szcześniak, Hanna Borkowska, Weronika Bojdo, Urszula Zofia Myszak

Faculty of Social Sciences, Institute of Psychology, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland

Correspondence: Małgorzata Szcześniak, Email [email protected]

Background: The ability to integrate beauty (AIB) is the ability to inner transformation including thinking about oneself, perceived phenomena, or the world through exposure to an aesthetic object (or phenomenon). Previous research indicates that the AIB is positively related to aesthetic experience. Still, it is unclear whether spirituality can mediate the relationship between the two variables. Spirituality is understood as an experience of transcendence that relates to the unseen and is “larger than human”. The aim of the study was to analyze the relationship between emotional and cognitive experiences related to the reception of art (as the most representative form of beauty) and the ability to connect with spirituality and aesthetic experiences.

Methods: The online survey included a sample of N = 195 adults (74% female) between the ages of 18 and 54. The Spirituality Scale (SD-36), the Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire (AEQ) and the Ability to Integrate Beauty Scale (AIBS) were used to test hypotheses.

Results: The analysis revealed a statistically significant, moderate relationship between the ability to integrate beauty and both the total aesthetic experience score and the spirituality scale score. The results support the hypothesis that there is a relationship between aesthetic experience in art and spirituality. The study also confirmed the mediating effect of spirituality on the relationship between aesthetic experience and aesthetic intelligence.

Conclusion: Individuals with a higher level of spiritual development tend to have a greater ability to integrate beauty and have more intense aesthetic experiences, which in turn may increase their aesthetic intelligence. The results suggest that a deepened spirituality contributes to a greater ability to integrate beauty.

Keywords: aesthetic experience, beauty, spirituality, ability to integrate beauty

Introduction

The ability to integrate beauty is the ability to change one’s being through contact with an aesthetic object (or phenomenon). This transformation is multi-dimensional, profound and felt as encompassing the whole being. Ferrucci1 defines this ability as one of the three components of aesthetic intelligence, along with the ability to perceive beauty in different situations (range of beauty) and the feeling of being deeply moved by beauty (depth of experience).

According to Ferrucci,1 humans are born with an innate ability to perceive and appreciate beauty. While some people see beauty in works of art of a particular trend or period, others are able to find it in everyday situations (the sight of the sky, the reflection of light or the sounds of nature). In addition, some people believe that their encounter with beauty triggers a transformative process within them. In addition to purely physical sensations (shivers, chills) or emotional feelings (fascination, rapture), they begin to think differently about themselves and the world; they feel they have discovered a truth or are inspired to do something new. Perhaps this internal transformation may be related to the process of art reception proposed by Kowalik2 in his book, which suggests that individuals can fill the three areas of cognitive void through the experience of art.

Kowalik2 writes that cognitive void is a feeling of lack of knowledge. Metaphysical void concerns whether and what is beyond our ontological reality (the feeling of emptiness may also result from the assumption that there is nothing more, although one would like it to exist). The epistemic void involves experiencing a lack of knowledge or uncertainty within the ontological space (people assume that there is or may be something worth introducing into our epistemic space; for example, scientific research is an objectified, structured way of filling this void). Existential void refers to not knowing oneself (people discover that their knowledge of themselves is not complete by observing their own and other people’s behavior). Contact with various forms of pieces of art is contact with the expression of the artist’s inner life (their experiences, their attempt to cope with the cognitive void). That is, the recipients discover or/and fill their own cognitive void thanks to the fact that the artist did it. Art can lead to filling the emptiness one or more types at a time. It is not a one-time process, but a multiple one.

Psychotherapist and philosopher Ferruci’s three-factor concept of aesthetic intelligence is virtually absent from psychological research and the literature.3 This is surprising, as Pelowski and his research team4 identified a significant gap in the psychology of art and aesthetics seven years ago. Current models and theoretical discourses tend to explain the process of aesthetic perception but often overlook the importance of art for individuals and society. The development of a scale measuring the third dimension of aesthetic intelligence3 has provided an opportunity to explore how the integration of beauty contributes to the development of specific traits and well-being. It also raises questions about the relationship of aesthetic intelligence to other traits or abilities. Therefore, this article seeks to answer the question of the role of aesthetic experience and spirituality in the development of beauty integration abilities.

Integration of Beauty

The third aspect of aesthetic intelligence, the ability to integrate beauty, sounds like an enigma. According to Ferrucci,1 it is the ability to change one’s being under the influence of contact with beauty. It could be argued that an inner transformation is a unique form of aesthetic intelligence, as it involves a heightened awareness of one’s inner states, such as thoughts, beliefs and emotions. By experiencing a profound encounter with what one finds beautiful, an individual can experience an emotional and cognitive response and become aware of a change taking place within themselves.

The ability to integrate beauty shows that there are other motives and functions involved in the search for beauty than the purely sensual pleasure of encountering an aesthetic object (or phenomenon). Individuals may actively seek beauty as a means of gaining new perspectives on situations, phenomena, themselves, or events, with the goal of being internally enriched not only by the aesthetic experience, but also by the insights and inspirations it provides. Research by Fancourt et al5 suggests that engaging in aesthetic creativity can contribute to the achievement of new insights or self-improvement goals. Kowalik2 suggests that receiving art means turning inwards and deepening one’s inner life. We believe that any encounter with beauty, whether through works of art or otherwise, as long as it is a profound experience, has the potential to help us achieve our goals. Diessner has written about the benefits of seeing and appreciating beauty in different forms.6–8

Notably, Ferrucci1 does not view aesthetic intelligence as a purely innate trait but rather as something that individuals can develop and enhance throughout their lives. Dan et al9 take a similar stance, writing about the construction and validation of their own scale to measure the aesthetic quotient. This indicates that, for the majority of people, aesthetic intelligence can serve as a valuable tool for personal growth. Art students are often thought to have higher levels of aesthetic intelligence than non-art students,9 suggesting that frequent and intense aesthetic experiences may play an important role in the development of aesthetic integration skills.

Aesthetic Experience

Aesthetic experience has a long history as an object of study in European philosophy.10 At the same time, among psychological studies of art perception, the concept of “aesthetic experience” is described as poorly defined.11,12 It undoubtedly refers to the external perception (looking, listening) of various objects, disregarding their functional use. According to Francuz et al,13 aesthetic experience is the result of several factors related to the evaluation of artwork, with the quality of the artwork and the expertise of the viewer playing a crucial role.

Some researchers define it as preferences and various emotional reactions.14 Others talk about emotions and cognitive states.15 Pelowski and Akiba16 proposed an authoritative model that describes the process of aesthetic experience itself in relation to art. Jankowski et al17 [p. 2] write about “three components: evaluative, affective and semantic”. Wanzer et al18 [p. 113] state that aesthetic experience is “the attitudes, perceptions, or acts of attention associated with viewing art”. They suggest that the intensity of aesthetic experience can be measured through inspection, taking into account several aspects such as the emotional aspect (feelings that arise in response to contact with a work of art), the perceptual aspect (attention to the structure, colors and details of the work), the cultural aspect (placing oneself in a wider context) and the understanding aspect (knowledge of the artwork and the artist). They also include two elements related to a particular state of mind, namely flow (the conditions that promote flow and the experience of flow itself). The aesthetic experience is most often discussed in the context of artworks, but it should be added that nature can also be its source.19–22

Despite its universal nature, aesthetic experience stands out from other experiences as significantly rewarding and memorable.23 It is known that people with more aesthetic experiences report stronger aesthetic experiences.18 Other research has shown that people who score high on the Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire are not only more aesthetically competent, but also more cognitively inclined and more likely to turn to artistic creation and music to manage their emotions.24 Suwiński25 writes that the experience of beauty is a fundamental aspect of human existence, which manifests itself in cognitive processes as either pleasure or preference.

Spirituality

Spirituality is a complex and multifaceted concept. It can be understood as an integrating factor of life, personality, and human development and relates to the significance of events that an individual gives meaning to.26 The cognitive domain is an inherent aspect of an individual’s everyday life and is reflected in their particular activities and inner experiences.27 In Bożek et al,28 spirituality is presented as an experience of transcendence that can be either internal, such as self-actualization, or external, such as a connection with a higher being, energy or the universe. Unlike religion, spirituality is not institutional, ritualistic, and does not have to be communal (spirituality can develop powerfully in interaction with others, but does not require belonging to a formal or informal formation group). Instead, it focuses on the individual’s personal experience of that which is invisible and “greater than human”. Spirituality can manifest itself through religiosity, but although the two constructs are similar, they are not the same thing. Socha29 organizes the knowledge of spirituality by describing its components, which include the aesthetic sense (sensitivity to art). On the other hand, Ma and Wang,30 in their text, further elaborate on the concept of spiritual intelligence. A highly intellectual person is characterized by: self-awareness, spontaneity, vision and idea-driven, holistic, compassion, appreciation of difference, independence, humility, ability to contextualize, positivity in handling adversity, vocation awareness, and desire to understand and explore. It is worth noting that although spirituality is associated with positive traits, it has also been found to correlate with beliefs in the paranormal and pseudoscientific.31 Furthermore, spirituality cannot be understood as something fixed (domains or dimensions) but as a “process of coping with an existential situation”32 [p. 267]. Despite different ways of defining and measuring spirituality, the literature still refers to its significant links with subjective well-being, health-related quality of life, coping, and recovery from mental health problems or self-destructive behavior.28 Spirituality is also positively correlated with age and female gender.33

If sensitivity to art is shown to be an aspect of spirituality, spirituality could contribute to more intense aesthetic experiences. At the same time, aesthetic experiences could result in a deepening of an individual’s spirituality. It is also known, for example, that music has accompanied important life rites and rituals for centuries.34 Today, it remains an element of religious events, fostering feelings of sublimity, reverence and awe. The aesthetic experience could support the human tendency towards transcendence. From the perspective of theological aesthetics, beauty can be read as elevating the human mind toward contemplation.25 Furthermore, another publication argues that aesthetic experiences contribute to spiritual well-being.35 Wynn,35 writing on spirituality, refers to religious spirituality rather than spirituality in the psychological sense. On page 406 he wrote:

I began this paper by suggesting that aesthetic values appear to be important for many forms of lived religion, given the wide interest of religious traditions in, for example, the arts and in the regulation of the disposition of the body in worship or devotion.

It can be assumed that people who report stronger aesthetic experiences also have a more strongly developed spiritual domain.

Hypotheses

The present study examines the relationship between emotional and cognitive sensations associated with the reception of art as the most representative form of beauty, as well as aesthetic experiences and the ability to integrate the human mental domain. Our aim was also to explore the importance of the spiritual aspect concerning aesthetic intelligence.

Four research hypotheses were formulated based on the information presented in the introduction. The first three hypotheses proposed were implicitly derived from the literature presented earlier. However, as the study of aesthetic intelligence is an emerging field of psychology and, consequently, as there are no data available to describe in depth the relationship between the variables studied, our hypotheses are partially exploratory in nature:

H1: Aesthetic experience is positively related to the ability to integrate beauty. H2: Aesthetic experience is positively related to spirituality. H3: Spirituality is positively related to the overall ability to integrate beauty.

However, the fourth hypothesis requires a separate justification. In our study, we chose aesthetic experience as the explanatory variable and the ability to integrate beauty as the explained variable. We hypothesize that the explanation of having had strong aesthetic experiences may predict a higher ability to incorporate beauty and may also indicate a more highly developed spiritual domain (the quest for transcendence, the search for the sacrum). At the same time, spirituality seems to be the area of life facilitating “inner transformation” under the influence of beauty. Following Socha,29 if we assume that artistic sensibility is a domain of spirituality, spirituality should reinforce the influence of experience on the development of aesthetic intelligence. The fact that spirituality appears as such in various psychological research reports36–41 speaks in favor of placing spirituality in the role of mediator. It was therefore assumed that:

H4: Spirituality mediates the relationship between aesthetic experience and the ability to integrate beauty.

Research Design, Research Tools, and Statistical Analyses

Participants

The survey was conducted among N = 195 adult Poles, 74% of whom were women. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 54 years (M = 27.12; SD = 8.19). The survey was web-based, using random sampling and the snowball method. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the survey, how it would be conducted, the estimated duration, the option to stop participating at any time, and the anonymity and confidentiality of individual results. Respondents were also provided with an email address to contact the researchers. Once the research team was assembled, online access to the test battery was deactivated. The study was conducted under the Research Ethics Committee approval of the Institute of Psychology at the University of Szczecin (No. 6/2022) and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All participants gave fully informed, written consent. The following instruments were used in the study: the Spirituality Scale, the Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire, and the Ability to Integrate Beauty Scale.

Measures

The Spirituality Scale – SD-3642 is a 36-item Polish psychometric tool. It measures spirituality as a trait, which the authors defined in six ways based on Socha’s conceptualization.29 The tool is thus used to measure: religious spirituality, spirituality understood as the expansion of consciousness, spirituality as the search for meaning, spirituality as sensitivity to art, spirituality as the doing of good, and spirituality as sensitivity to inner and outer beauty. The respondents are asked to rate each statement on a 4-point scale, with a score of 1 representing “definitely no” and a score of 4 representing “definitely yes”. The total score is the sum of all scores, and the scores for the individual subscales are calculated by adding the scores of the statements that make up the subscales. In this study, the reliability rates for the dimensions and the total score ranged from α = 0.76 to α = 0.97 for the individual subscales. The reliability index for the total score was very high (α = 0.93). For the purpose of the study, the overall score was used for statistical analysis rather than the subscales.

The Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire – The AEQ18 in the Polish version of Świątek et al24 is an instrument used to measure aesthetic experience. Four subscales relate to dimensions related to art (emotional, cultural, perceptual, and understanding), and two more relate to the concept of flow during the aesthetic experience of interacting with art. The questionnaire consists of 22 questions to which respondents answer on a seven-point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 7 being strongly agree. The total score is obtained by adding up all the scores obtained by the respondent. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for individual aspects of aesthetic experience was high, ranging from α = 0.84 to α = 0.92. For the overall score for aesthetic experience, the coefficient was α = 0.95. The overall score was used in the statistical analyses.

The Ability to Integrate Beauty Scale – The AIBS3 is an instrument measuring, in Ferrucci’s terms, the third dimension of aesthetic intelligence, which includes the ability to integrate beauty. The AIBS is a short, single-factor, 7-item scale that assesses the intensity of an inner sense of change as a result of aesthetic experiences. Subjects respond to all statements on a 7-point Likert scale (strongly disagree = 1, to strongly agree = 7). The total score is obtained by summing up the scores obtained by the respondent. The AIBS Cronbach’s α coefficient for this study was high at 0.95.

Statistic Analyses

To answer the research questions presented and to test the hypotheses, statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 and the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 3.2). The variables of aesthetic experience, spirituality, and beauty integration were controlled for the normality distribution, assuming skewness (< ±2) and kurtosis (< ±2) criteria.43 The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and the tolerance statistic were used to quantify collinearity.44 The coefficient of VIF higher than 5.0 and the tolerance value lower than 0.2 were considered as indices of the suspected multicollinearity. The Mahalanobis and the Cook’s distance were checked for potentially misleading outliers. In case of the Mahalanobis method we adopted a chi-square criterion (degrees of freedom = 4) and p < 0.001. The Cook’s distance value close to 1 or more was considered to call for investigation.45

Stepwise regression analysis included two potential confounders (sex, age) in the first step. Two predictors (aesthetic experience and spirituality) were selected in the second step. Although we do not have much research on the differences in terms of aesthetics and beauty due to gender and age, there is some evidence that both variables could act as potential confounders. For example, Zhang et al46 observed that visual aesthetic sensitivity increases with age and is significantly higher in girls than in boys. Similarly, spirituality in older persons47–49 and women50 tends to increase.

Results

Statistical Analyses and Correlations

The variables of aesthetic experience, spirituality, and beauty integration were controlled for normal distribution by assuming skewness (< ±2) and kurtosis (< ±2) criteria.43 Using a statistically significant (p < 0.001) normality test, the skewness and kurtosis measures were within a relatively normal range ±1.

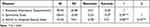

Table 1 illustrates the strength of the correlation between the variables in the study. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for total scores shows a moderate, statistically significant relationship between total aesthetic experience score and beauty integration ability (H1), between aesthetic experience and total spirituality scale score (H2), and between spirituality and beauty integration (H3).

|

Table 1 Mean, Standard Deviation (SD) and Correlations of the Study Variables (N = 195) |

Multicollinearity, Outliers, and Confounders

The Variance Inflation Factor values varied between 1.030 and 1.238 (below the level of 5). The lowest tolerance was 0.808 (beyond 0.2). Both indices confirmed no presence of multicollinearity in the present data set. The Mahalanobis distance for multivariate outlier detection did not reveal any observations with chi-squared values of less than 0.001 (the lowest was = 0.00125). Likewise, the Cook’s distance values ranged between 0.000 and 0.079. Thus, both measures corroborated that the outliers were not problematic in the sample.

The linear regression model showed that sex (β = −0.030, t = −0.512, p = 0.609) and age (β = 0.003, t = 0.050, p = 0.960) explained barely 0.5% of the variance (R2= 0.005). Aesthetic experience (β = 0.490, t = 7.928, p = 0.001) and spirituality (β = 0.239, t = 3.787, p = 0.001) represented a significant amount of the variance (additional 38.6%) despite of controlling for the confounding effects of sex and age.

Mediating Effect of Spirituality

In order to verify the hypothesis of the mediating role of spirituality in the relationship occurring between aesthetic experience and aesthetic intelligence – understood as the ability to integrate beauty – a mediation model No 4 with a single mediator was selected (Figure 1), and the Bootstrapping 5000 technique was applied with adjusted confidence intervals (95% IC).

|

Figure 1 Results of mediation analysis of spirituality in the relationship between aesthetic experience and beauty integration. *** p < 0.001. |

It was checked whether the condition of mediation was fulfilled, ie, path a (the relationship between aesthetic experience and spirituality) and path b (the relationship between spirituality and the integration of beauty) were analyzed. The results show that high intensity of reported aesthetic experiences predicted high levels of spirituality (β = 0.2627; p < 0.001). In addition, a stronger spirituality was found to predict a higher ability to integrate beauty (β = 0.1284; p < 0.001).

The next step was to validate the proxy using a bootstrapping method that assumed a non-zero 95% confidence interval. The results show that the influence of aesthetic experience has a statistically significant indirect effect on the ability to integrate beauty, with spirituality acting as a mediator (95% CI: 0.0137; 0.0562). The value of the indirect effect was 0.0337, and B(SE) = 0.0109. In addition, the β value of the c pathway was found to decrease with the β value of the c’ pathway, confirming the mediating effect of spirituality (H4).

Discussion

The results of the statistical analysis confirmed all four hypotheses presented. Moreover, the intensity of aesthetic experience predicts higher levels of spirituality, which in turn is a predictor of the third dimension of aesthetic intelligence. It is difficult to contrast the results obtained with the reports of other researchers because we could not find studies that analyzed these three variables, but we tried to discuss them anyway.

A positive correlation was found between aesthetic sensations and the ability to associate beauty and spirituality (H1, H2). In our study, the intensity of aesthetic sensations was measured in the context of reactions to the exploration of artworks. This measure includes not only emotional, perceptual, or flow components but also, for example, understanding the artwork, knowledge about the artist, the culture, and the conditions under which the artwork was created. The perception of art is something much more complex (actual or symbolic representation, intention, meaning given by the creator) than the sights or sounds of nature. Furthermore, Ferrucci1 believes that the ability to integrate beauty is a universal skill that does not require knowledge or artistic preparation. Therefore, all we have proven is that people who are sensitive to art (who can understand it, ie, have some knowledge of art) are more likely to integrate beauty and be more spiritual than those who are less sensitive to art. However, what about people who are highly sensitive to non-artistic beauty (ie, natural beauty or, for example, mathematical beauty)?51,52 At this stage of research, we are not able to answer this question.

The hypothesis of the co-occurrence of intense spirituality and higher ability to integrate beauty was also confirmed (H3). Spirituality and aesthetics are related in philosophical and theological literature. Beauty, along with truth and goodness, is one of the transcendentals.53–56 Our findings imply that spirituality, which is a broader concept than religiosity (and may or may not include religiosity), can predict the third dimension of aesthetic intelligence.

With reference to the fourth hypothesis (H4), our results suggest that perhaps it is the developed spiritual domain that enables people to “construct” meaningful aesthetic experiences and “transform” themselves internally. Of course, our study does not allow us to verify to what extent the sense of internal transformation is just an autosuggestion and to what extent it is a fact. It is known that while the experience of profound beauty has the potential to transform personality, it does not itself appear to induce long-term change.57 These considerations should be confirmed in panel or experimental studies.

The question arises, of course, whether the spiritual sphere is necessary for developing aesthetic intelligence, given the critical direct link between aesthetic experience and the integration of beauty. Maybe there is some other “bridge” or feature of the human psyche that favors this relationship without considering spirituality. It was difficult for us to find an empirical justification that it is not. Since spirituality can be understood as a process, transformation, in general,29 we believe that it contributes to the development of aesthetic intelligence by reassessing aesthetic experiences, making them meaningful, or giving them new meanings.

Our research also suggests that the transformations associated with being influenced by beauty and spiritual transformation should not be set as independent of or in opposition to each other, as Cohen et al57 investigated. The ability to integrate beauty, shaped by aesthetic experience and informed by a deepened spirituality, could hypothetically be a resource for the psychological growth of the individual for more permanent personality changes.

Limitations

The study design may raise concerns about the reliability of the survey responses. Questionnaires completed via the Internet, despite efforts to eliminate erroneous, unreliable, or untruthful responses, may still raise concerns about the reliability of the results obtained. Furthermore, the sample needs to be larger to be generalizable to the whole population, and the respondents were mainly women.

The interpretative framework is also determined by the survey instruments used, which refer to specific theories or paradigms. Concepts such as spirituality or aesthetic experience pose similar difficulties for researchers – they can be defined in many different ways, yet we have a limited number of measurement tools available. It is important to consider the paradigms within which the variables were operationalized when using the results of this study in other works.

Another possible caveat is that the study did not consider the participants’ artistic experience. Specialized art training is likely to influence the level of aesthetic intelligence. On the other hand, Ferrucci’s book emphasizes the universality of beauty – the fact that it is accessible to all and that it is present in the everyday lives of ordinary people as long as they can perceive it. You do not need any/extensive knowledge of art history or music or a regular visits to the opera house to see the beauty of a flower in bloom or the common blackbird singing. Our initial premise was to test hypotheses about factors that contribute to a high ability to integrate beauty without dividing the sample into aesthetic experts and non-experts; further research on the ability to incorporate beauty should consider the level of artistic expertise of the participants.

Conclusions

The results show that people who experience aesthetic experiences more intensely are characterized by higher aesthetic intelligence if they have a more highly developed spiritual domain. Arguably, deepened spirituality is conducive to perfecting the ability to integrate beauty. The simultaneous measurement of both constructs in the context of spirituality has yet to be analyzed in detail. Hence, the results presented here are a good starting point for further research on aesthetic intelligence.

Data Sharing Statement

All data have been made publicly available at OSF and can be accessed at https://osf.io/g94tn/?view_only=ae7b4633896e4745bfca6fcd6490b7fc.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Ferrucci P. Beauty and the Soul: The Extraordinary Power of Everyday Beauty to Heal Your Life. Penguin; 2009. ISBN 978-1585428335.

2. Kowalik S. Siedem wykładów z psychologii sztuki [Seven lectures of art psychology]. Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka; 2020. ISBN 978-83-8116-970-7.

3. Świątek AH, Szcześniak M. The Ability to Integrate Beauty Scale (AIBS): construction and psychometric properties on a scale for measuring aesthetic intelligence as a resource for personal development. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:1647–1662. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S407553

4. Pelowski M, Markey PS, Lauring JO, Leder H. Visualizing the impact of art: an update and comparison of current psychological models of art experience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00160

5. Fancourt D, Garnett C, Spiro N, West R, Müllensiefen D. How do artistic creative activities regulate our emotions? Validation of the Emotion Regulation Strategies for Artistic Creative Activities Scale (ERS-ACA). PLoS One. 2019;14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211362

6. Diessner R, Steiner P. Interventions to increase trait appreciation of beauty. Indian J Posit Psychol. 2017;8:401–406.

7. Diessner R, Pohling R, Stacy S, Güsewell A. Trait appreciation of beauty: a story of love, transcendence, and inquiry. Rev Gen Psychol. 2018;22(4):377–397. doi:10.1037/gpr0000166

8. Rastogi M. Review of understanding the beauty appreciation trait: empirical research on seeking beauty in all things. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2022;16(3):571–572. doi:10.1037/aca0000489

9. Dan Y, Wu C, Yang M. Development and validation of the aesthetic competence scale. Advance Preprint. 2021. doi:10.31124/advance.17075180.v1

10. Stroud SR. John Dewey and the Artful Life: Pragmatism, Aesthetics, and Morality. Penn State University Press; 2021. ISBN 978-0271050089.

11. Redies C, Tesli M, Bettella F, Djurovic S, Andreassen OA, Melle I. Combining universal beauty and cultural context in a unifying model of visual aesthetic experience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:9. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00218

12. Brattico E, Bogert B, Jacobsen T. Toward a neural chronometry for the aesthetic experience of music. Front Psychol. 2013;4. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00206

13. Francuz P, Zaniewski I, Augustynowicz P, Kopiś N, Jankowski T. Eye movement correlates of expertise in visual arts. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00087

14. Vessel EA, Starr GG, Rubin N. Art reaches within: aesthetic experience, the self and the default mode network. Front Neurosci. 2013;7. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00258

15. Leder H, Ring A, Dressler SG. See me, feel me! Aesthetic evaluations of art portraits. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2013;7(4):358–369. doi:10.1037/a0033311

16. Pelowski M, Akiba F. A model of art perception, evaluation and emotion in transformative aesthetic experience. New Ideas Psychol. 2011;29(2):80–97. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2010.04.001

17. Jankowski T, Francuz P, Oleś P, Chmielnicka-Kuter E. The effect of temperament, expertise in art, and formal elements of paintings on their aesthetic appraisal. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2020;14(2):209–223. doi:10.1037/aca0000211

18. Wanzer DL, Finley KP, Zarian S, Cortez N. Experiencing flow while viewing art: development of the aesthetic experience questionnaire. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2020;14(1):113–124. doi:10.1037/aca0000203

19. Chenoweth RE, Gobster PH. The nature and ecology of aesthetic experiences in the landscape. Landsc J. 1990;9(1):1–8. doi:10.3368/lj.9.1.1

20. Diessner R, Woodward D, Stacy S, Mobasher S. Ten once-a-week brief beauty walks increase appreciation of natural beauty. Ecopsychology. 2015;7(3):126–133. doi:10.1089/eco.2015.0001

21. Løvoll HS, Sæther KW, Graves M. Feeling at home in the wilderness: environmental conditions, well-being and aesthetic experience. Front Psychol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00402

22. Graves M, Løvoll HS, Sæther KW. Friluftsliv: aesthetic and psychological experience of wilderness adventure. Issues Sci Religion. 2020;5:207–220. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-31182-7_17

23. Shusterman R. Przekłady: o końcu i celu doświadczenia estetycznego [Translations: on the end and purpose of aesthetic experience]. Er(r)go Teoria Literatura Kultura. 2006;12:129–151.

24. Świątek AH, Szcześniak M, Wojtkowiak K, Stempień M, Chmiel M. Polish version of the Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire (AEQ): validation and psychometric characteristics. Front Psychol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1214929

25. Suwiński M. Duchowość piękna, flos carmeli wydawnictwo warszawskiej prowincji karmelitów bosych. Poznań 2014, -pp. 267. Teol Czl. 2015;29:327–332. doi:10.12775/TiCz.2015.016

26. Kapała M. Duchowość jako niedoceniany aspekt psyche. Propozycja nowego ujęcia duchowości w psychologii – kategoria wrażliwości duchowej [Spirituality as an underestimated aspect of the psyche. A proposal for a new approach to spirituality in psychology - the category of spiritual sensitivity]. Ann Univ Mariae Curie-Sklodowska. 2017;1:7–37. doi:10.17951/j.2017.30.1.7

27. Heszen-Niejodek I. Wymiar duchowy człowieka a zdrowie. In: Juczyński Z, Ogińska-Bulik N, editors. Zasoby osobiste i społeczne sprzyjające zdrowiu jednostki [The spiritual dimension of man and health. In: Personal and social resources enabling individual health]. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego; 2003:33–47.

28. Bożek A, Nowak PF, Blukacz M, Dutt V. The relationship between spirituality, health-related behavior, and psychological well-being. Front Psychol. 2020;11:11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01997

29. Socha PM. Duchowy rozwój człowieka. Fazy życia, osobowość, wiara, religijność [Spiritual development of man. Stages of life, personality, faith, religiosity]. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego; 2000. ISBN 83-233-1276-6.

30. Ma Q, Wang F. The role of students’ spiritual intelligence in enhancing their academic engagement: a theoretical review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:6.

31. Nowak B, Brzóska P, Piotrowski J, Żemojtel-Piotrowska M, Jonason P. Disentangling the effects of religiosity and spirituality on contaminated mindware; 2022. doi:10.31234/osf.io/fqav5

32. Socha PM. Duchowość jako przemiana. Nowa teoria duchowości i jej zastosowanie w badaniach [Spirituality as transformation. A new theory of spirituality and its application in research]. Rel Duch. 2010;2010:262–274.

33. Jeste DV, Thomas ML, Liu J, et al. Is spirituality a component of wisdom? Study of 1,786 adults using expanded San Diego Wisdom Scale (Jeste-Thomas Wisdom index). J Psychiatr Res. 2021;132:174–181. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.033

34. Moss H. Music therapy, spirituality and transcendence. Nord J Music Ther. 2019;28(3):212–223. doi:10.1080/08098131.2018.1533573

35. Wynn M. Aesthetic experience and spiritual well-being: locating the role of theological commitments. Int J Philos Theol. 2018;79(4):397–409. doi:10.1080/21692327.2018.1475250

36. Temane QM, Wissing MP. The role of spirituality as a mediator for psychological well-being across different contexts. South African J Psychol. 2006;36(3):582–597. doi:10.1177/008124630603600309

37. Trigwell JL, Francis AJ, Bagot KL. Nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: spirituality as a potential mediator. Ecopsychology. 2014;6(4):241–251. doi:10.1089/eco.2014.0025

38. Jimenez-Fonseca P, Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ, et al. The mediating role of spirituality (meaning, peace, faith) between psychological distress and mental adjustment in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1411–1418. doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3969-0

39. Perez JA, Peralta CO, Besa FB. Gratitude and life satisfaction: the mediating role of spirituality among Filipinos. J Beliefs Values. 2021;42(4):511–522. doi:10.1080/13617672.2021.1877031

40. Soósová MS, Timková V, Dimunová L, Mauer B. Spirituality as a mediator between depressive symptoms and subjective well-being in older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(5):707–717. doi:10.1177/1054773821991152

41. Bali M, Bakhshi A, Khajuria A, Anand P. Examining the association of gratitude with psychological well-being of emerging adults: the mediating role of spirituality. Trends Psychol. 2022;30(4):670–687. doi:10.1007/s43076-022-00153-y

42. Skowroński B, Bartoszewski J. Skala Duchowości – opis konstrukcji i właściwości psychometryczne. Psych Psychoter. 2017;3:3–29.

43. Bachman LF. Statistical Analyses for Language Assessment. Cambridge University Press; 2004. ISBN 978-0-511- 62961-7.

44. Yan X, Su X. Linear Regression Analysis: Theory and Computing. World Scientific Publishing; 2009. ISBN 978-981-283-410-2.

45. Maindonald JH, Braun J. Data Analysis and Graphics Using R: An Example-Based Approach. Cambridge University Press; 2010. ISBN 978-0521762939.

46. Zhang J, Du X, Zhang X, Bai X. The development of visual aesthetic sensitivity in students in China. Front Psychol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1071487

47. Maobe A. The overlay between demographic characteristics, spirituality and retirement planning, Kenya expose. Cogent Soc Sci. 2020;6. doi:10.1080/23311886.2020.1831147

48. MahdiNejad J, Azemati H, Habibabad AS, Matracchi P. Investigating the effect of age and gender of users on improving spirituality by using EEG. Cogn Neurodyn. 2021;15(4):637–647. doi:10.1007/s11571-020-09654-x

49. Moberg DO. Research in spirituality, religion and aging. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2005;45(1–2):11–40. doi:10.1300/J083v45n01_02

50. Bryant AN. Gender differences in spiritual development during the college years. Sex Roles. 2007;56(11–12):835–846. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9240-2

51. Sa R, Alcock L, Inglis M, Tanswell FS. Do mathematicians agree about mathematical beauty? Rev Philos Psychol. 2023;1–27. doi:10.1007/s13164-022-00669-3

52. Montano U. Explaining Beauty in Mathematics: An Aesthetic Theory of Mathematics. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. ISBN 978-3319034515.

53. Maryniarczyk A. Transcendentalia w perspektywie historycznej. Od arché do antytranscendentaliów [Transcendentals in historical perspective. From arché to anti-transcendentals]. Roczniki Filozoficzne. 1995;43:139–164.

54. Gardner H, Gardner G. Truth, Beauty, and Goodness Reframed: Educating for the Virtues in the Twenty-First Century. Basic Books; 2011. ISBN 978-1441780539.

55. Ramos A. Dynamic Transcendentals: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty from a Thomistic Perspective. CUA Press; 2012. ISBN 978-0813219653.

56. Seul A. The truth. The goodness. the beauty. Wrocl Przegl Teolog. 2019;27:97–122. doi:10.34839/wpt.2019.27.1.97-122

57. Cohen AB, Gruber J, Keltner D. 2010 comparing spiritual transformations and experiences of profound beauty. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2010;2(3):127–135. doi:10.1037/a0019126

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.