Back to Journals » Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation » Volume 9

Adapting substance use brief interventions for adolescents: perspectives of adolescents living with adults in substance use disorder treatment

Authors Padwa H , Guerrero EG, Serret V , Rico M, Gelberg L

Received 21 June 2018

Accepted for publication 22 September 2018

Published 5 December 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 137—142

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S177865

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Li-Tzy Wu

Howard Padwa,1 Erick G Guerrero,2,3 Veronica Serret,2 Melvin Rico,4 Lillian Gelberg4–6

1University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2University of Southern California, Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 3University of Southern California, Marshall School of Business, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 4University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 5University of California, Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 6Department of Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Office of Healthcare Transformation and Innovation, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Background: Brief interventions (BIs) have shown potential to reduce both alcohol and drug use. Although BIs for adults have been studied extensively, little is known about how to adapt them to meet the needs and preferences of adolescents. This article examines adolescents’ preferences to consider when adapting BIs for use with adolescents.

Methods: Eighteen adolescents (age 9–17 years) living in Los Angeles County with adults receiving substance use disorder treatment were interviewed and asked about their perspectives on how to adapt a BI originally developed for adults for use with adolescents. Questions focused on adolescents’ preferences for who should deliver BIs, how BIs should be delivered, and what content they would want to be included in BIs. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using summative content analysis.

Results: Adolescents did not express any discernable opinions concerning who delivers BIs or what content they would want to be included, but they did share perspectives on how BIs should be delivered. Most adolescents did not endorse incorporating text messaging or social media into BIs. Instead they preferred having BIs delivered face-to-face or over the telephone. They reported that they did not want BIs to incorporate text messaging or social media due to concerns about trust, the quality of information they would receive, and challenges communicating in writing instead of speaking.

Conclusion: Although the study has limitations because of its small sample size, findings indicate that adolescents may not want text messaging or social media to be incorporated into BIs for substance use. These findings warrant further research and consideration, particularly as work to enhance BIs for adolescents continues.

Keywords: adolescents, substance use, brief interventions, SBIRT, health communication preferences

Introduction

In the USA, adolescent substance use remains a significant public health problem.1,2 Approximately 9.2% of US adolescents aged 12–17 years report having used alcohol in the previous month, and 7.9% report past month drug use.3 These adolescents are at increased risk for injury, motor vehicle accidents, risky sexual behavior, victimization, substance use disorders, and neurodevelopmental issues that result from the use of psychoactive substances.4,5

Brief interventions (BIs) – conversations that focus on encouraging healthy choices and reducing risk behaviors – hold promise as tools that can help motivate adolescents to reduce their substance use.6–14 BIs focus on facilitating behavior change among adolescents who are using alcohol and/or drugs but do not have a substance use disorder or adolescents who have a mild-to-moderate substance use condition. For adolescents who are using alcohol/drugs but do not have a disorder, BIs include clear and pointed advice for adolescents to reduce substance use and succinct mention of the potential negative health effects of alcohol and drugs. For those who are using substances more heavily or frequently, BIs involve the use of motivational interviewing strategies to help adolescents compare the benefits of continued use with the potential benefits of behavior change (cutting back, stopping) to empower them to make decisions that support their health, safety, and achievement of personal goals.5,6

Meta-analyses have shown that BIs for adolescents can be effective; BIs lead to small but significant reductions in alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and drug use among adolescents.15–17 However, the evidence base concerning the effectiveness of substance use BIs for adolescents is not as strong as it is for adults,18 and the United States Preventive Services Task Force maintains that current evidence concerning the benefits of BIs to address adolescent alcohol and drug use is insufficient.19,20 Consequently, there is interest in adapting existing Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) models that were developed for adults for use with adolescents in order to enhance their effectiveness.18

Evidence shows that some BI characteristics – such as the use of motivational interviewing, goal-setting exercises, involvement of caregivers, and having more than one session – are associated with stronger effects.15,16,18 There is increasing interest in leveraging this knowledge, together with insights from developmental theory, to adapt BIs for use with adolescents. In particular, Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment for Adolescents (SBIRT-A) is a set of recommended adaptations to substance use screening and BI approaches for use with adolescents. SBIRT-A involves several key adjustments to BIs, including 1) utilizing risk algorithms to determine what type of BI adolescents will receive; 2) increased use of computer-based interventions; 3) emphasis on psychoeducation; 4) the addition of booster sessions to BIs; and 5) the incorporation of caregivers into discussions about substance use.18

Although these adaptations are highly promising, little is known about their acceptability to adolescent patients. Research has identified adolescents’ preferences regarding substance use screening, showing that adolescents prefer paper forms and computerized questionnaires over interviews with service providers when having initial discussions about substance use.21 However, adolescents’ preferences regarding BIs have not yet been explored. In particular, it is unknown if adolescents have preferences concerning who delivers BIs, how BIs are delivered, or what content they include. Because there is interest in adapting BIs for adolescents by making significant changes to who is involved in BIs (caregivers), their delivery (via computer), and their content (psychoeducation),18 information concerning the acceptability of these potential alterations is needed. This article is an initial step toward identifying adolescent preferences for BIs based on a series of interviews with adolescents.

Methods

Interviews were conducted with a sample of 18 adolescents as part of a project examining the feasibility and acceptability of adapting a substance use BI protocol tested on adults – the Quit Using Drugs Intervention Trial (QUIT) intervention22,23 – for use with adolescents who are at high risk for substance use because they live in homes with adults who are in substance use disorder treatment.24,25 The QUIT intervention involves having a clinician provide brief advice (3–4 minutes) concerning the health consequences of substance use, reinforced by a message from a video doctor, a health education booklet, and up to two 20- to 30-minute follow-up coaching sessions with a health educator.22,23 Interviews conducted for this study focused on getting adolescents’ perspectives on QUIT and potential adaptations to the intervention based on SBIRT-A recommendations.

Study sample

Adolescents were eligible to participate if they were between the ages of 9 and 17 years and regardless of whether or not they had a history of alcohol or drug use. Participants were identified indirectly through programs in Los Angeles County where their parents or caregivers were receiving substance use disorder treatment. At each program, clients with adolescent children were recruited through flyers and announcements in group meetings and invited to have their families participate in the study. Interested parents/caregivers gave written informed consent to allow project staff to invite their children to participate in the study. Project staff then met with adolescents in private spaces in their homes, where parents, siblings, and other individuals could not overhear conversations. Written informed consent was obtained from each adolescent before interviews began. Participants received a $50 gift card. All study recruitment, enrollment, and data collection procedures were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board.

Data collection and interview

Interviews were conducted by research staff trained in interviewing methods by a PhD-level qualitative researcher with extensive experience conducting interviews with diverse patient populations (including adolescents). The interviews were semistructured and began with questions about prevention services adolescents had received and a description of the QUIT protocol. Interviewers then asked each adolescent open-ended questions about who they would prefer to deliver BIs for alcohol and/or drug use, how they would like BIs to be delivered, and what content they would like to be incorporated into BIs. Table 1 includes the questions asked in the course of each interview. Most of the interviews lasted ~30 minutes.

| Table 1 Interview guide questions |

Data coding and analysis

All interviews were transcribed and analyzed in Dedoose analytic software using summative content analysis – a method that involves measuring the frequency of specific ideas while also discovering meanings and contexts underlying them.26 Sections of transcripts where adolescents were asked about who they would like to deliver BIs were coded to indicate if respondents preferred for physicians, health educators, counselors, peers, or other individuals to deliver BI services. Sections of transcripts that focused on how BIs would be delivered were coded to indicate if adolescents preferred in-person delivery, having them delivered by telephone, through text messaging, or through social media platforms. Sections of transcripts that focused on content of BIs were coded to indicate if adolescents endorsed having BIs educate them about the health consequences of substance use if they should include other content as well. Sections of transcripts where adolescents discussed their perspectives on parental involvement in discussions about substance use were coded to indicate if they endorsed parental involvement or did not think it would be beneficial. In cases when respondents did not give answers, said they did not know, or said they did not have an opinion, transcripts did not receive a code.

Each interview was coded independently by two researchers with training in qualitative analysis. After completing their initial coding, the researchers reviewed each other’s coding, discussed cases where there were discrepancies, and reached 100% consensus on all coding and data interpretation.

Results

Study sample

Table 2 provides an overview of the study sample. Interviewees were all between the ages of 9 and 17 years, and the mean age was 13.72 years. The majority of the sample was female and Hispanic/Latino.

| Table 2 Interviewee characteristics (N=18) |

BI preferences

Interviews did not reveal adolescent perspectives concerning who they would like to deliver BIs, what content they would like to see in BIs, or parental involvement in BIs. The majority of interviewees said that they did not know or that they did not have an opinion on these issues. However, interviews did show that adolescents had preferences concerning how interventions should be delivered (in person, by speaking on the telephone, through text messaging, over social media).

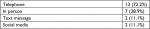

Table 3 describes how often each delivery option (in person, talking on the phone, by text message, or using social media) was endorsed by adolescents. The majority of interviewees (72.2%) endorsed having BIs over the telephone, and over 38% endorsed in-person BIs, while only a small number (11.1%) endorsed the use of text messaging or social media.

| Table 3 Adolescents’ preferred mode of substance use brief intervention delivery (N=18) Note: Some respondents endorsed more than one method. |

During interviews, adolescents elaborated on their preferences, highlighting that they preferred in-person and telephone modes of delivery because of concerns about trust and the reliability of information obtained via text message and social media and because of the relative ease of communication over the phone and in face-to-face conversations. Adolescents reported that even though they often use social media and text messaging, they did not feel that these media would be conducive to discussions about substance use. “Online,” elaborated one adolescent, “I would not feel safe. Because (when I talk about these things) what if it is someone I do not know?” In addition to issues of trust, adolescents reported that they felt correspondence that occurs through social media or text message is often unreliable and “just not believable.”

Conversely, adolescents reported that they would feel more at ease if BIs were delivered either in person or over the telephone. They explained that face-to-face and telephone communications are more trustworthy and that they could communicate more effectively using methods that did not require them to write. “I just think it is easier to talk on the phone because sometimes you have so much to say and it comes right as you’re talking.” Another adolescent concurred, saying that “I do not know how to describe how I feel with paper, so I think on the phone would be better because it is more of what I say aloud than text or social media.”

Discussion

Interviews did not provide information concerning adolescent preferences for who delivers BIs, the content of BIs, or parental involvement in BIs but they did provide perspective on adolescents’ preferences for how they should be delivered. Further research is needed to determine adolescents’ preferences concerning who delivers BIs, the content of BIs, and parental involvement in BIs.

Interviews indicated that adolescents prefer oral communication (phone calls, face-to-face conversations) over written communication (text messages, social media) when receiving BIs focused on substance use. They expressed preference for speaking to someone over the phone or in person due to concerns about trust, the reliability of information, and challenges communicating when interacting through text messaging or social media.

Study findings are notable since there is interest in utilizing computerized BIs when adapting them for use with adolescents.18 Although computerized interventions have demonstrated strong clinical impacts when compared with other BIs in effectiveness studies,18,27,28 findings from this study indicate that adolescents may prefer BIs that allow them to directly speak with a person – either on the telephone or face-to-face. Future research will be needed to determine if the benefits of computerized interventions (e.g. reduced practitioner burden, minimization of provider differences in implementation fidelity, maximization of information process efficiency, flexibility to allow self-guided response-sensitive intervention delivery)18 outweigh the potential discomfort that adolescents may have with computerized BIs.

Adolescent preferences for BIs that involve speaking (rather than reading and writing via text or social media) are also notable since research indicates that adolescents prefer written tools for substance use screening.21 Findings from this study indicate that while adolescents may prefer to initially disclose substance use on paper or via computer rather than to a person, they may prefer to have different types of interactions (over the phone, face-to-face) when receiving services focused on changing substance use behaviors. However, the fact that more adolescents preferred communicating over the phone instead of in-person indicates that they may still prefer to not have conversations about substance use that do not require them to discuss sensitive topics face-to-face with adults.21 Future efforts to adapt and enhance BIs for adolescents may need to incorporate strategies that reflect these concerns.

Some of the main reasons adolescents elaborated for preferring telephone and in-person communication – concerns about trust and reliability of text messaging and social media – have been acknowledged as areas that can potentially limit the utility of technology when providing health interventions on sensitive topics such as substance use.29–31 Findings that adolescents believe technological interventions may not be trustworthy or reliable may help explain results from other studies where adolescents did not prefer technological interventions over other types of services to address risky behaviors.31

Study findings also support research showing that if interventions concerning highly sensitive behaviors (eg, substance use, sex) are going to be provided to adolescents using text messaging or social media, it will be essential to assure adolescents that these interventions are trustworthy and safe.32 If text messaging or social media are incorporated into BIs for adolescents, they will need to be sufficiently secure and designed to safeguard adolescents’ privacy.

Limitations of the study should be noted. The study sample was small, predominantly represented by Latino females recruited from one urban area, and consisted of adolescents living with adults who were in substance use disorder treatment. It is possible that respondents’ views are not generalizable to adolescents in other regions or from other race/ethnicities. Furthermore, interviewees’ perspectives may have been colored by their experiences with substance use living in homes with adults who needed treatment. This could have made study participants more sensitive to some issues than a general adolescent population would be. More research is needed to explore these areas in greater detail, particularly to determine to what extent findings reported here reflect the BI preferences of adolescents from different areas and demographics, and those who do not have family members with histories of problem substance use.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study indicates that it may be beneficial to deliver BIs for adolescents in person or over the telephone rather than using text messaging or social media. Further research into these areas – both adolescents’ preferences and the impact that adolescents’ reported levels of comfort with different types of communication may have on BIs’ effectiveness – is needed. The insights reported in this article may be useful for both researchers and providers to consider as they continue developing strategies to address the negative impact substance use has on their adolescent patients’ health and well-being.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R33DA035634-03S1.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(6):607–615. | ||

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use: 1975–2013: Overview of Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. | ||

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. | ||

Feinstein EC, Richter L, Foster SE. Addressing the critical health problem of adolescent substance use through health care, research, and public policy. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(5):431–436. | ||

Levy SJ, Williams JF. Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161211. | ||

Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. SBIRT for adolescent drug and alcohol use: current status and future directions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(5):463–472. | ||

Winters KC, Botzet AM, Fahnhorst T. Advances in adolescent substance abuse treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(5):416–421. | ||

Committee on Substance Abuse, Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1330–e1340. | ||

Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989–994. | ||

Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):396–402. | ||

Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1234–1243. | ||

Bernstein E, Edwards E, Dorfman D, Heeren T, Bliss C, Bernstein J. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1174–1185. | ||

D’Amico EJ, Miles JN, Stern SA, Meredith LS. Brief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: a randomized pilot study in a primary care clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(1):53–61. | ||

Winters KC, Leitten W. Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21(2):249–254. | ||

Carney T, Myers B. Effectiveness of early interventions for substance-using adolescents: findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:25. | ||

Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;51:1–18. | ||

Tanner-Smith EE, Steinka-Fry KT, Hennessy EA, Lipsey MW, Winters KC. Can brief alcohol interventions for youth also address concurrent illicit drug use? Results from a meta-analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(5):1011–1023. | ||

Ozechowski TJ, Becker SJ, Hogue A. SBIRT-A: adapting SBIRT to maximize developmental fit for adolescents in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;62:28–37. | ||

Moyer VA. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(3):210–218. | ||

Moyer VA. Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(9):634–639. | ||

Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening instruments for substance use and brief interventions targeting adolescents in primary care: a literature review. Addict Behav. 2013;38(5):2146–2153. | ||

Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Afifi AA, et al. Project QUIT (Quit Using Drugs Intervention Trial): a randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based multi-component brief intervention to reduce risky drug use. Addiction. 2015;110(11):1777–1790. | ||

Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Rico MW, et al. A pilot replication of QUIT, a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for reducing risky drug use, among Latino primary care patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:433–440. | ||

Clark DB, Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Childhood risk categories for adolescent substance involvement: a general liability typology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77(1):13–21. | ||

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1–2):165–177. | ||

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. | ||

Ridout B, Campbell A. Using Facebook to deliver a social norm intervention to reduce problem drinking at university. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(6):667–673. | ||

Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Goldstein A, et al. Three-month follow-up of brief computerized and therapist interventions for alcohol and violence among teens. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1193–1207. | ||

Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, Hoving C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e85. | ||

Yonker LM, Zan S, Scirica CV, Jethwani K, Kinane TB. “Friending” teens: systematic review of social media in adolescent and young adult health care. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e4. | ||

Ranney ML, Choo EK, Spirito A, Mello MJ. Adolescents’ preference for technology-based emergency department behavioral interventions: does it depend on risky behaviors? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(4):475–481. | ||

Selkie EM, Benson M, Moreno M. Adolescents’ views regarding uses of social networking websites and text messaging for adolescent sexual health education. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42(4):205–212. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.