Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

A review of immediacy and implications for provider–patient relationships to support medication management

Authors Bartlett Ellis R , Carmon A, Pike C

Received 26 August 2015

Accepted for publication 29 October 2015

Published 7 January 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 9—18

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S95163

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Rebecca J Bartlett Ellis,1 Anna F Carmon,2 Caitlin Pike3

1Science of Nursing Care, Indiana University School of Nursing, Indianapolis, 2Communication Studies, Indiana University Purdue University Columbus, Columbus, IN, 3IUPUI University Library, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Objectives: This review is intended to 1) describe the construct of immediacy by analyzing how immediacy is used in social relational research and 2) discuss how immediacy behaviors can be incorporated into patient–provider interventions aimed at supporting patients’ medication management.

Methods: A literature search was conducted using Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Google Scholar, OVID, PubMed, and Education Resource Information Center (ERIC) EBSCO with the keyword “immediacy”. The literature was reviewed and used to describe historical conceptualizations, identify attributes, examine boundaries, and identify antecedents and consequences of immediacy.

Results: In total, 149 articles were reviewed, and six attributes of immediacy were identified. Immediacy is 1) reciprocal in nature and 2) reflected in the communicator’s attitude toward the receiver and the message, 3) conveys approachability, 4) respectfulness, 5) and connectedness between communicators, and 6) promotes receiver engagement. Immediacy is associated with affective learning, cognitive learning, greater recall, enhanced relationships, satisfaction, motivation, sharing, and perceptions of mutual value in social relationships.

Conclusion: Immediacy should be further investigated as an intervention component of patient–provider relationships and shared decision making in medication management.

Practice implications: In behavioral interventions involving relational interactions between interveners and participants, such as in medication management, the effects of communication behaviors and immediacy during intervention delivery should be investigated as an intervention component.

Keywords: patient–provider communication, health communications, medication management, patient education, health behavior

Introduction

Effective patient–provider communication contributes to patients’ understanding of their illnesses, treatment options, and adherence, which is imperative for disease management.1 Poor provider–patient communication often distances patients from participation in their care,2 which is associated with 1.5 times greater risk for treatment non-adherence,3 with medication non-adherence occurring in as many as 50% of patients. Patient factors, such as not understanding medications and instructions, can lead to unintentional non-adherence.4 In the USA, surveys of patients discharged from acute care hospitals have found that when a new medicine was being explained to them, only 65% reported that they had “always” been told what the medicine was for and what side-effects might be experienced.5 When patients do not adequately understand how to care for themselves after discharge, they are more likely to experience hospital re-admission. Avoidable hospital re-admission within 30 days of discharge occurs in as many as one in five elderly patients, and unnecessary re-admissions cost the federal government an additional $17 billion annually, because patients are not prepared to self-manage their illnesses after discharge.6 Active patient engagement in relationships with providers facilitates patient decision making, which is imperative in promoting effective medication management.

Interpersonal relationships can be enhanced through communication behaviors that convey a sense of interpersonal closeness, which is also known as immediacy. In learning situations, intervener immediacy is associated with certain learner attitudes and perceptions, such as interest in content and state motivation, in relation to learning.7 Understanding immediacy and how it can affect the provider–patient relationship can help inform self-management interventions; however, such studies of immediacy in health care are limited. The purpose of this article is twofold. The first purpose is to describe the concept of immediacy in communication and how it has been used in relational and educational research. The second purpose is to discuss how immediacy behaviors can be incorporated into patient–provider communication interventions aimed at supporting patients with medication management.

Defining immediacy

Immediacy is most often found in the field of communication research and has been less studied in the health care environment. Immediacy behaviors are “approach behaviors” conveying interpersonal closeness that increases sensory stimulation, which is perceived as warmth.8 The construct of immediacy refers to perceptions of physical and/or psychological closeness among individuals.9 These behaviors can include physically moving closer to someone during interaction, touching, using direct eye contact, smiling, having an open body posture, gesturing, and vocal expressiveness.10 While the study of non-verbal communication is not novel, immediacy encompasses more than just non-verbal behaviors. Immediacy is an affect-based construct, where communication behaviors reflect the underlying psychology between those communicating.

Literature review

A literature review was used to define immediacy by 1) examining conceptual boundaries, 2) identifying critical attributes, and 3) identifying antecedents and consequences. The literature was located thorough database search engines CINAHL, Google Scholar, OVID, PubMed, and ERIC EBSCO from 1968 to 2014 using the keyword “immediacy” in the title of articles. Searches were limited to English full-text articles. Based on the selection criteria, 404 articles were identified. Abstracts were reviewed to determine if the articles pertained to immediacy in interpersonal (relational) communication. Articles that did not pertain to this criterion (eg, reference to timing of events, alcohol drinking, reward, publishing, and Internet) were excluded.

Results

Historical views of immediacy

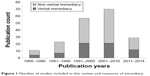

After removing duplicates and screening articles, 149 articles remained that met review criteria. Historically, immediacy was studied from the communication perspective. Immediacy in communication is attributed to Mehrabian,11 who described the concept as a directness and intensity in communication, known as the “immediacy principle”. From 1966 onward, scholars have increasingly studied verbal and non-verbal immediacy, as shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Number of studies included in this review and measures of immediacy. |

Recent communication scholars have modified the original immediacy principle as the “principle of immediate communication”, suggesting “the more communicators employ immediate behaviors, the more others will like, evaluate highly, and prefer such communicators; and the less communicators employ immediate behaviors, the more others will dislike, evaluate negatively, and reject such communicators”.12 This suggests that individuals, who engage in immediacy behaviors, are more likely to be liked than individuals who do not engage in immediacy behaviors. These two principles suggest a reciprocal relationship between immediacy and liking, and over time, both have been supported and seen as correct.13

Dimensions (measures)

Measurement of immediacy was described as both subjective and objective across studies in this review. Immediacy measures included both self-report and observer rating scales. Verbal and non-verbal aspects of communication have been measured in studying immediacy. Regardless of whether immediacy was measured verbally or non-verbally, immediacy was described as a “perception of psychological closeness”,10,14–33 reflecting the underlying psychology of interpersonal communication. Both behaviors have been considered “artifacts of affect” and therefore have been used as surrogate/latent constructs to measure immediacy. In only one study, physiological dimensions were analyzed in relationship to anxiety and its effect on blood pressure ratings.34

Verbal immediacy

Mehrabian and Wiener’s early work examined linguistic features of communication.35 His approach considered that immediacy cues were encoded in the communicator’s word choices and reflected the communicator’s attitude toward the referent or object of communication, including their liking and preference toward such referents. Directness of the interaction and relationship between the communicator and referent could, therefore, be inferred from the communicator’s word choices. For example, a communicator’s word choices reflected the extent to which the receiver of the message was considered as a member of the communicator’s associated groups or was considered as an outsider. Early immediacy research focused on the communicators’ directness and intensity encoded in words.36–38 Gorham39 later approached verbal immediacy by asking students to describe their best teachers and specific behaviors that helped characterize them as such. This approach resulted in the construction of a measure of verbal immediacy, which is known as the verbal immediacy scale (VIS). Despite the VIS being widely used across studies included in our review,16,18,21–26,28,39–65 it has been criticized as being a measure of teaching effectiveness and not necessarily being a measure of immediacy.59,66

Further work to develop a measure of verbal immediacy was undertaken by Mottet and Richmond.67 Their work suggested that people use a variety of verbal strategies to pursue relationships that are not necessarily based on the linguistic code. They developed verbal typologies that represent strategies people employ to build or avoid relationships. Although verbal strategies are useful in making people appear more or less approachable, Mottet and Richmond67 contended that approach-avoidance strategies do not actually comprise verbal immediacy. Instead, they believed that VISs were measures of relational approach and avoidance.

Non-verbal immediacy

Non-verbal behaviors have long been studied in communication research; however, most studies of non-verbal behavior have assessed just one or two behaviors. Non-verbal behaviors as they naturally occur involve several behaviors that when combined are likely to reflect the communicator’s attitude. Non-verbal immediacy behaviors include observable objective behaviors such as touch, proximity, eye contact, verbal expressions, and tone of voice.

Andersen et al8 combined several different non-verbal behaviors to operationalize non-verbal immediacy. Andersen et al’s work resulted in the simultaneous development of three instruments: 1) generalized immediacy scale, 2) behavioral indicants of immediacy scale, and 3) trained rater’s perception of immediacy scale.8 These scales were developed to address measurement concerns in establishing both subjective and objective measures, as well as a means to establish construct validity. The behavioral indicants of immediacy scale has been considered problematic because learners are asked to compare their teacher against another teacher and the scale has item redundancy.68 Building on these limitations, Gorham and Zakahi51 generated a 14-item instrument combining items from Andersen’s early work and researcher-generated items to balance positively and negatively worded items. This revised instrument, non-verbal immediacy measure, was later reduced to ten items69 and was used primarily across the last decade. Use of these instruments indicated some potential reliability problems, with reliability estimates ranging from 0.67 to 0.89. As a result, the non-verbal immediacy scale was constructed.70 This newer scale includes a self-report and observer versions and has since been used in communication research, with reliability estimates of 0.90.70

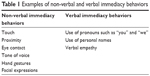

Given the literature included in this review, immediacy can best be conceptualized and measured as a multi-dimensional construct consisting of both verbal and non-verbal components. Non-verbal and verbal immediacy components are outlined in Table 1.

| Table 1 Examples of non-verbal and verbal immediacy behaviors |

Contextual influences

Immediacy has been studied mainly in a few different disciplines including psychotherapy, linguistics, and predominately, in education. In studies reviewed, the core of immediacy is the “interpersonal relationship”. The types of relationships examined are shown in Table 2. Immediacy was primarily limited to adults or college-aged students.

| Table 2 Contextual influences (not mutually exclusive) |

In all studies, communication occurred either face-to-face or online; in most cases, the interpersonal relationship was between one and many, such as in the classroom. In a number of articles,40,41,44,52,71–74 immediacy was related to the “here and now” meaning both parties’ communication behaviors conveyed involvement and engagement in the present conversation. When those behaviors were utilized, there were descriptions of “presence”. Focus on affect in the relationship influenced immediacy, whereas distancing behaviors were described as more information seeking/gathering with no affect. Because of the context studied, including classroom and psychotherapy, immediacy was studied in the context of powerful relationships. One additional study investigated source immediacy in the context of authority. In this study, immediacy was studied in relation to the actual presence of the authority figure and behavioral responses depended on presence.75 Certain types of relationships (eg, teacher/student and therapist/client) create power differentials.76

While immediacy was studied in communication studies, psychotherapy researchers also investigated immediacy as an intervention in client and psychotherapist relationships. Collingwood and Renz,77 for example, evaluated the therapeutic interaction between a counselor and his/her client. Expressed in these relationships were communications that conveyed empathy and respect, as well as communication that focused on the “here and now” of the relationship. For example, if the client talked about the counselor and their relationship or if the counselor related the content of client discussions to the relevant content at hand, this was considered indicative of immediacy. The study of immediacy and specific types of immediacy were further developed from interaction analysis in case studies across time78,79 and then from more generalized, descriptive, and longitudinal studies of immediacy.80 More recent literature defines immediacy as observable events between a patient and psychotherapist that includes disclosure of the here-and-now, expressed by either the client or the psychotherapist71 and is a part of the therapeutic process.81

Attributes

In reviewing the literature, we have postulated six specific attributes of immediacy: respectfulness, approachability, connectedness, attitude, engagement, and reciprocity. These attributes are not mutually exclusive. Immediacy attributes were identified based on authors’ descriptions of immediacy and measures of immediacy. Definitions of immediacy most often referenced Mehrabian82 and Andersen et al.83 The term immediacy is often used interchangeably with “immediacy cues”; however, immediacy is the affective response, whereas immediacy cues are the specific behaviors that lead to immediacy perceptions.84

Immediacy is reflected in the communicator’s attitude toward the receiver and the message, conveys approachability, stimulates interest in the receiver, conveys connectedness between communicators, and promotes receiver engagement in communication; therefore, it is reciprocal in nature.

Antecedents

Antecedents of immediacy were rarely explicitly described; two broad antecedents were implied based on definitions of immediacy and contexts within which immediacy was studied. The first antecedent is proximity. Any situation that places people in proximity to one another presents the opportunity for people to interact. For example, in educational research, the classroom was the context that permitted interaction. Web-based environments, though they do not involve face-to-face interaction, were also important contexts that led to interaction.16,19,40,41,47,56,72,87,93,109,126,127,130,142

The second antecedent is the use of verbal and non-verbal immediacy cues that signal “liking”. This antecedent is derived from studies that based their immediacy definition on Mehrabian’s work,11 which considers immediacy as a manifestation of liking.14,16,37,50,96,101,144,155 Implied in this definition is that when a person likes another person, he or she will engage in more immediacy behaviors. Andersen et al8 described this as engagement in non-verbal communication behaviors that signal approach, availability, and openness and signal the beginning of a relationship.

Consequences

Immediacy is associated with affective learning, cognitive learning, greater recall, enhanced relationships, satisfaction, motivation, sharing, and perceptions of mutual value in the relationship (Table 3). These outcomes were evaluated by both correlational descriptive and experimental designs. Those who are more immediate are considered more assertive and responsive to others’ needs than those who are less immediate.66 This likely has to do with the fact that immediate individuals are considered communicatively competent,66 meaning that they can effectively and appropriately communicate with a variety of individuals in different situations and contexts.

| Table 3 Consequences of immediacy |

Interactive communication is indicative of greater collaboration and shared decision making.17 In the few studies that focused on health care, including the physician and psychotherapist relationships, use of immediate behaviors was associated with patient satisfaction, increased attention, and more sharing, as well as medical competence, humility, and access.20,148 Immediacy has also been associated with one’s ability to elicit emotional sharing, including interpersonal connection, trust, and caring.16,20,34,77,141,154

Immediacy behaviors, in general, are positively related to cognitive learning, but not all immediacy behaviors have the same effect. Specifically, vocal expressiveness, smiling, and relaxed body posture had the greatest effect on cognitive learning, whereas touch had the least effect.111 This suggests that as individuals try to increase cognitive learning, regardless of the context, it may behoove them to concentrate on improving specific immediacy behaviors, rather than trying to improve all immediacy behaviors. In general, those viewed as immediate were considered approachable, encouraging, and effective.

Discussion of immediacy in medication management intervention

Immediacy is a relationship-based construct that encompasses both verbal and non-verbal communicative behaviors in a way that increases attention and psychological closeness among individuals. In the educational contexts studied, immediacy has been associated with affective learning, increased motivation to learn, and increased cognitive mastery. In the few health care-related contexts that have been studied, immediacy resulted in greater personal reflection,156 as well as greater connection among providers and patients, with patients working more closely to achieve important health goals.154 Although the educational context is different from the health care context, both education and health care environments involve relationships between people, who support others’ learning and skill acquisition. Health care providers often assume instructional teaching roles in providing patient education. In these teaching roles, the health care provider must engage the patient in learning; this includes using strategies to enhance affect toward learning and motivation. Given that there is a cumulative body of evidence suggesting that immediacy has been effective in enhancing these very outcomes, it is likely to have the same effect in the context of patient education. If medical providers employ immediacy behaviors, then it is more likely to engage the patient, leading to shared decision making and then better preparation for self-management of prescribed medications.

Increased attention is being paid to shared decision making in the health care context; yet, inclusion of immediacy in this relationship is yet to be explored. Furthermore, in behavioral interventions involving relationships between interveners and participants, the effects of the perceived immediate behaviors by research participants of the interveners delivering interventions are yet to be investigated. For example, intervener immediacy may be just as important as intervention fidelity for interventions involving interpersonal communication with patients. This means that patients’ perceptions derived from provider use of high or low immediate behaviors may interact with behavior change efforts, such as medication management. If there is an interaction between participant perception of intervener immediacy and the outcome, results of interventions delivered in the social relational context may be stronger or weaker than what is actually reported.

The concept of provider immediacy may be useful in designing interventions to support medication management. To date, several different approaches to enhance adherence and medication management have been studied. These interventions have focused on patient education, counseling, and post-discharge follow-up to assess adherence.157 In studies investigating patient–provider relationships, patient perception of provider communication has correlated with medication adherence. Liu et al158 studied hormone treatment therapy following breast cancer diagnoses in low-income women and found that communication perception was linked with adherence to medication treatment. Furthermore, the oncologist’s patient-centered communication was an independent predictor of sustained adherence at 36 months after diagnosis. Providing patient education and counseling at discharge with improved health care provider communication has been shown to reduce patients’ risk for adverse medication problems and re-admissions.159 Though interventions have targeted enhanced communication with patients, most studies have been of poor quality or were underpowered159 and lacked focus on the relational communication aspects of immediate communication behaviors.

Conclusion

By employing immediacy behaviors, health care providers are more likely to draw patients’ attention to important educational points. More importantly, when providers employ immediacy behaviors, they are more likely to engage patients in a dialogue that will enhance the provider–patient relationship. This enhanced relationship is likely to assist patients in feeling more comfortable while discussing their plans of care and what is most meaningful for them in the context of their own lives. Thus, by enhancing relationships with patients, providers can enhance shared decision making and patients’ self-management behaviors. Incorporating personalized components of communication and immediacy in interventions is needed in medication management research and practice.

Implications for research and practice

Researchers and practitioners should consider the potential immediacy effects on targeted outcomes. It is hypothesized that non-verbal behaviors account for 80% of communication between individuals.160 Interveners, who interact with patients, may use behaviors that increase immediacy or distance the patient from communication. These behaviors may alter the patient’s attention to important educational messages, beliefs in the content, and trust in the relationship, all of which may modify the outcome of interest (eg, medication management and adherence). Therefore, as interventions are designed to support medication management, incorporating communication behaviors known to enhance immediacy should be considered in intervention design, intervener selection, and intervention fidelity. Including patients’ self-report of immediacy as well as objective measurement of immediacy can inform how immediacy may affect medication adherence interventions. Immediacy measures can be useful in understanding patient perceptions of the communication behaviors used in delivering interpersonally based interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Dimatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002; 40(9):794–811. | ||

Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, et al. Communication and medication refill adherence: the diabetes study of Northern California. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(3):210–218. | ||

Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. | ||

Lindquist LA, Go L, Fleisher J, Jain N, Friesema E, Baker DW. Relationship of health literacy to intentional and unintentional non-adherence of hospital discharge medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; 27(2):173–178. | ||

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Summary of HCAHPS Survey Results [July 2013 to June 2014 Discharges]. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015. | ||

Goodman D, Fisher E, Chang C. The revolving door: a report on us hospital readmissions. Lebanon, New Hampshire: Dartmouth Atlas Project; 2013. | ||

Witt PL, Wheeless LR, Allen M. A meta-analytical review of the relationship between teacher immediacy and student learning. Commun Monogr. 2004;71(2):184–207. | ||

Andersen JF, Andersen PA, Jensen AD. The measurement of nonverbal immediacy. J Appl Commun Res. 1979;7(2):153–180. | ||

Gottlieb R, Wiener M, Mehrabian A. Immediacy, discomfort-relief quotient, and content in verbalizations about positive and negative experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967;7(3p1):266–274. | ||

Kay B, Christophel DM. The relationships among manager communication openness, nonverbal immediacy, and subordinate motivation. Commun Res Rep. 1995;12(2):200–205. | ||

Mehrabian A. Immediacy: an indicator of attitudes in linguistic communication. J Pers. 1966;34(1):26–34. | ||

Richmond VP, McCroskey JC. The impact of supervisor and subordinate immediacy on relational and organizational outcomes. Commun Monogr. 2000;67(1):85–95. | ||

Richmond VP, McCroskey JC, Johnson AD. Development of the nonverbal immediacy scale (NIS): measures of self-and other-perceived nonverbal immediacy. Commun Q. 2003;51(4):504–517. | ||

Allen JL, Long KM, O’Mara J. Communication apprehension, generalized and contextual immediacy and achievement in the basic course. In: Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association; 1985; Denver, CO. | ||

Allen M, Witt PL, Wheeless LR. The role of teacher immediacy as a motivational factor in student learning: using meta-analysis to test a causal model. Commun Educ. 2006;55(1):21–31. | ||

Bailie JL. The criticality of verbal immediacy in online instruction: a modified Delphi study. J Educ Online. 2012;9(2):1–22. | ||

Chory RM, McCroskey JC. The relationship between teacher management communication style and affective learning. Commun Q. 1999; 47(1):1–11. | ||

Christophel DM. The relationships among teacher immediacy behaviors, student motivation, and learning. Commun Educ. 1990;39(4): 323–340. | ||

Conaway RN, Easton SS, Schmidt WV. Strategies for enhancing student interaction and immediacy in online courses. Business Commun Q. 2005;68(1):23–35. | ||

Conlee CJ, Olvera J, Vagim NN. The relationships among physician nonverbal immediacy and measures of patient satisfaction with physician care. Commun Rep. 1993;6(1):25–33. | ||

Frymier AB. The impact of teacher immediacy on students’ motivation: is it the same for all students? Commun Q. 1993;41(4):453–464. | ||

Frymier AB. Immediacy and Learning: A Motivational Explanation. Washington, DC: Presented at: Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association; 1993, Washington, DC. | ||

Frymier AB. A model of immediacy in the classroom. Commun Q. 1994;42(2):133–144. | ||

Gendrin DM, Rucker ML. Revisiting the relation between teacher immediacy and student learning in African American college classrooms. Atl J Commun. 2004;12(2):77–92. | ||

Gendrin DM, Rucker ML. Student motive for communicating and instructor immediacy: a matched-race institutional comparison. Atl J Commun. 2007;15(1):41–60. | ||

Gorham J, Christophel DM. The relationship of teachers’ use of humor in the classroom to immediacy and student learning. Commun Educ. 1990;39(1):46–62. | ||

Henning ZT. From barnyards to learning communities: student perceptions of teachers’ immediacy behaviors. Qual Res Rep Commun. 2012;13(1):37–43. | ||

Moore A, Masterson JT, Christophel DM, Shea KA. College teacher immediacy and student ratings of instruction. Commun Educ. 1996;45(1):29–39. | ||

Mottet TP, Parker-Raley J, Cunningham C, Beebe SA, Raffeld PC. Testing the neutralizing effect of instructor immediacy on student course workload expectancy violations and tolerance for instructor unavailability. Commun Educ. 2006;55(2):147–166. | ||

Pogue LL, AhYun K. The effect of teacher nonverbal immediacy and credibility on student motivation and affective learning. Commun Educ. 2006;55(3):331–344. | ||

Roach KD, Cornett-Devito MM, Devito R. A cross-cultural comparison of instructor communication in American and French classrooms. Commun Q. 2005;53(1):87–107. | ||

Sidelinger RJ, Frisby BN, McMullen AL. Mediating the damaging effects of hurtful teasing: interpersonal solidarity and nonverbal immediacy as mediators of teasing in romantic relationships. Atl J Commun. 2012;20(2):71–85. | ||

Titsworth BS. The effects of teacher immediacy, use of organizational lecture cues, and students’ notetaking on cognitive learning. Commun Educ. 2001;50(4):283–297. | ||

Lee LA, Sbarra DA, Mason AE, Law RW. Attachment anxiety, verbal immediacy, and blood pressure: results from a laboratory analog study following marital separation. Pers Relatsh. 2011;18(2):285–301. | ||

Mehrabian A, Wiener M. Non-immediacy between communicator and object of communication in a verbal message: application to the inference of attitudes. J Consult Psychol. 1966;30(5):420–425. | ||

Eiser JR, Ross M. Partisan language, immediacy, and attitude changes. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1977;7(4):477–489. | ||

Gothberg H. Immediacy: a study of communication effect on the reference process. J Acad Librarianship. 1976;2(3):126–129. | ||

Slane S, Leak G. Effects of self-perceived nonverbal immediacy behaviors on interpersonal attraction. J Psychol. 1978;98(2):241–248. | ||

Gorham J. The relationship between verbal teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning. Commun Educ. 1988;37(1):40–53. | ||

Arbaugh JB. How instructor immediacy behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning in web-based courses. Bus Commun Q. 2001;64(4): 42–54. | ||

Baker C. The impact of instructor immediacy and presence for online student affective learning, cognition, and motivation. J Educ Online. 2010;7(1):1–30. | ||

Butland MJ, Beebe SA. Teacher immediacy and power in the classroom: the application of implicit communication theory. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association; 1992; Miami, FL. | ||

Christensen LJ, Menzel KE. The linear relationship between student reports of teacher immediacy behaviors and perceptions of state motivation, and of cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning. Commun Educ. 1998;47(1):82–90. | ||

Christophel DM, Gorham J. A test-retest analysis of student motivation, teacher immediacy, and perceived sources of motivation and demotivation in college classes. Commun Educ. 1995;44(4):292–306. | ||

Creasey G, Jarvis P, Gadke D. Student attachment stances, instructor immediacy, and student, Äìinstructor relationships as predictors of achievement expectancies in college students. J Coll Student Dev. 2009; 50(4):353–372. | ||

Ellis K. Apprehension, self-perceived competency, and teacher immediacy in the laboratory-supported public speaking course: trends and relationships. Commun Educ. 1995;44(1):64–78. | ||

Freitas FA, Myers SA, Avtgis TA. Student perceptions of instructor immediacy in conventional and distributed learning classrooms. Commun Educ. 1998;47(4):366–372. | ||

Frymier AB. The relationships among communication apprehension, immediacy and motivation to study. Commun Rep. 1993;6(1):8–17. | ||

Frymier AB, Thompson CA. Using student reports to measure immediacy: is it a valid methodology. Commun Res Rep. 1995;12(1):85–93. | ||

Georgakopoulos A, Guerrero LK. Student perceptions of teachers’ nonverbal and verbal communication: a comparison of best and worst professors across six cultures. Int Educ Stud. 2010;3(2):3–16. | ||

Gorham J, Zakahi WRA. Comparison of teacher and student perceptions of immediacy and learning: monitoring process and product. Commun Educ. 1990;39(4):354–368. | ||

Hackman MZ, Walker KB. Instructional communication in the televised classroom: the effects of system design and teacher immediacy on student learning and satisfaction. Commun Educ. 1990;39(3):196–206. | ||

Hess JA, Smythe M. Is teacher immediacy actually related to student cognitive learning? Commun Stud. 2001;52(3):197–219. | ||

Jaasma MA, Koper RJ. The relationship of student/faculty out-of-class communication to instructor immediacy and trust and to student motivation. Commun Educ. 1999;48(1):41–47. | ||

Neuliep JWA. Comparison of teacher immediacy in African-American and Euro-American college classrooms. Commun Educ. 1995;44(3): 267–277. | ||

Ni S-F, Aust R. Examining teacher verbal immediacy and sense of classroom community in online classes. Int J E-learning. 2008;7(3):477–498. | ||

Powell RG, Harville B. The effects of teacher immediacy and clarity on instructional outcomes: an intercultural assessment. Commun Educ. 1990;39(4):369–379. | ||

Roach KD. The influence of teaching assistant willingness to communicate and communication anxiety in the classroom. Commun Q. 1999;47(2):166–182. | ||

Robinson RY, Richmond VP. Validity of the verbal immediacy scale. Commun Res Rep. 1995;12(1):80–84. | ||

Sanders JA, Wiseman RL. The effects of verbal and nonverbal teacher immediacy on perceived cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning in the multicultural classroom. Commun Educ. 1990;39(4):341–352. | ||

Turman PD. Coaches’ immediacy behaviors as predictors of athletes’ perceptions of satisfaction and team cohesion. West J Commun. 2008; 72(2):162–179. | ||

Velez JJ, Cano J. Instructor verbal and nonverbal immediacy and the relationship with student self-efficacy and task value motivation. J Agric Educ. 2012;53(2):87–98. | ||

Velez JJ, Cano J. The relationship between teacher immediacy and student motivation. J Agric Educ. 2008;49(3):76–86. | ||

Walker KB, Hackman MZ. Information transfer and nonverbal immediacy as primary predictors of learning and satisfaction in the televised course. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association; 1991; Atlanta, GA. | ||

Wilson JH, Locker L Jr. Immediacy scale represents four factors: nonverbal and verbal components predict student outcomes. J Classroom Interact. 2008;42(2):4–10. | ||

Thomas CE, Richmond VP, McCroskey JC. The association between immediacy and socio-communicative style. Commun Res Rep. 1994; 11(1):107–114. | ||

Mottet TP, Richmond VP. An inductive analysis of verbal immediacy: alternative conceptualization of relational verbal. Commun Q. 1998; 46(1):25–40. | ||

McCroskey JC, Sallinen A, Fayer JM, Richmond VP, Barraclough RA. Nonverbal immediacy and cognitive learning: a cross-cultural investigation. Commun Educ. 1996;45(3):200–211. | ||

McCroskey JC, Fayer JM, Richmond VP, Sallinen A, Barraclough RA. A multi-cultural examination of the relationship between nonverbal immediacy and affective learning. Commun Q. 1996;44(3):297–307. | ||

Richmond VP, McCroskey JC, Johnson AD. Development of the Nonverbal Immediacy Scale (NIS): measures of self- and other-perceived nonverbal immediacy. Commun Q. 2003;51(4):504–517. | ||

Clemence AJ, Fowler JC, Gottdiener WH, et al. Microprocess examination of therapeutic immediacy during a dynamic research interview. Psychotherapy. 2012;49(3):317–329. | ||

Schutt M, Allen BS, Laumakis MA. The effects of instructor immediacy behaviors in online learning environments. Q Rev Dist Educ. 2009;10(2):135–148. | ||

Bozkaya M. The relationship between teacher immediacy behaviours and distant learners’ social presence perceptions in videoconferencing applications. The Turkish Online J Educ Tech. 2008;9(1):Article 12. | ||

Kasper LB, Hill CE, Kivlighan DM. Therapist immediacy in brief psychotherapy: case study I. Psychotherapy (Chicago, IL). 2008;45(3):281–297. | ||

Sedikides C, Jackson JM. Social impact theory: a field test of source strength, source immediacy and number of targets. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 1990;11(3):273–281. | ||

Plax TG, Kearney P, McCroskey JC, Richmond VP. Power in the classroom VI: verbal control strategies, nonverbal immediacy and affective learning. Commun Educ. 1986;35(1):43–55. | ||

Collingwood TR, Renz L. The effects of client confrontations upon levels of immediacy offered by high and low functioning counselors. J Clin Psychol. 1969;25(2):224–226. | ||

Hill CE, Sim W, Spangler P, Stahl J, Sullivan C, Teyber E. Therapist immediacy in brief psychotherapy: case study II. Psychother. 2008; 45(3):298–315. | ||

Kasper LB, Hill CE, Kivlighan DM. Therapist immediacy in brief psychotherapy: case study I. Psychother. 2008;45(3):281–297. | ||

Mayotte-Blum J, Slavin-Mulford J, Lehmann M, Pesale F, Becker-Matero N, Hilsenroth M. Therapeutic immediacy across long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: an evidence-based case study. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):27–40. | ||

Hill CE, Gelso CJ, Chui H, et al. To be or not to be immediate with clients: the use and perceived effects of immediacy in psychodynamic/interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2014;24:299–315. | ||

Mehrabian A. Silent Messages. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1971. | ||

Andersen, PA. Nonverbal immediacy in interpersonal communication. In: Siegman A and Feldstein (eds). Multichannel Integrations of Nonverbal Behavior. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1985:1–36. | ||

Kerssen-Griep J, Witt PL. Instructional feedback II: how do instructor immediacy cues and facework tactics interact to predict student motivation and fairness perceptions? Commun Stud. 2012;63(4):498–517. | ||

Bozkaya M, Erdem Aydin I. The relationship between teacher immediacy behaviors and learners’ perceptions of social presence and satisfaction in open and distance education: the case of Anadolu University Open Education Faculty. The Turkish Online J Educ Tech. 2007;6(4):Article 7. | ||

Burroughs NF. A reinvestigation of the relationship of teacher nonverbal immediacy and student compliance-resistance with learning. Commun Educ. 2007;56(4):453–475. | ||

Carrell LJ, Menzel KE. Variations in learning, motivation, and perceived immediacy between live and distance education classrooms. Commun Educ. 2001;50(3):230–240. | ||

Chesebro JL. Effects of teacher clarity and nonverbal immediacy on student learning, receiver apprehension, and affect. Commun Educ. 2003;52(2):135–147. | ||

Chesebro JL, McCroskey JC. The relationship of teacher clarity and teacher immediacy with students’ experiences of state. Commun Q. 1998;46(4):446–456. | ||

Chesebro JL, McCroskey JC. The relationship of teacher clarity and immediacy with student state receiver apprehension, affect, and cognitive learning. Commun Educ. 2001;50(1):59–68. | ||

Comstock J, Rowell E, Bowers JW. Food for thought: teacher nonverbal immediacy, student learning, and curvilinearity. Commun Educ. 1995;44(3):251–266. | ||

Estepp CM, Shelnutt KP, Roberts TG. A comparison of student and professor perceptions of teacher immediacy behaviors in large agricultural classrooms. NACTA J. 2014:58(2). | ||

Fall LT, Kelly S, Christen S. Revisiting the impact of instructional immediacy: a differentiation between military and civilians. Q Rev Distance Educ. 2011;12(3):199–206. | ||

Finn AN, Schrodt P. Students’ perceived understanding mediates the effects of teacher clarity and nonverbal immediacy on learner empowerment. Commun Educ. 2012;61(2):111–130. | ||

Freitas FA, Myers SA. Student perceptions of instructor immediacy in conventional and distributed learning classrooms. Commun Educ. 1998;47(4):366. | ||

Giorgi AJ, Roberts TG, Estepp CM, Conner NW, Stripling CT. An investigation of teacher beliefs and actions. NACTA J. 2013;57(3):2–9. | ||

Golish TD, Olson LN. Students’ use of power in the classroom: an investigation of student power, teacher power, and teacher immediacy. Commun Q. 2000;48(3):293–310. | ||

Goodboy AK, Myers SA. The relationship between perceived instructor immediacy and student challenge behavior. J Instructional Psychol. 2009;36(2):108–112. | ||

Goodboy AK, Weber K, Bolkan S. The effects of nonverbal and verbal immediacy on recall and multiple student learning indicators. J Classroom Interact. 2009;44(1):4–12. | ||

Gorham J, Cohen SH. Fashion in the classroom III: effects of instructor attire and immediacy in natural classroom. Commun Q. 1999;47(3):281–299. | ||

Johnson SD, Miller AN. A cross-cultural study of immediacy, credibility, and learning in the U.S. and Kenya. Commun Educ. 2002;51(3): 280–292. | ||

Kearney P, Plax T, Smith VR, Sorensen G. Effects of teacher immediacy and strategy type on college student resistance to on-task demands. Commun Educ. 1988;37(1):54–67. | ||

Kelley DH, Gorham J. Effects of immediacy on recall of information. Commun Educ. 1988;37(3):198–207. | ||

King P, Witt P. Teacher immediacy, confidence testing, and the measurement of cognitive learning. Commun Educ. 2009;58(1):110–123. | ||

Martin L, Mottet TP. The effect of instructor nonverbal immediacy behaviors and feedback sensitivity on hispanic students’ affective learning outcomes in ninth-grade writing conferences. Commun Educ. 2011;60(1):1–19. | ||

Menzel KE, Carrell LJ. The impact of gender and immediacy on willingness to talk and perceived learning. Commun Educ. 1999;48(1):31. | ||

Myers SA, Zhong M, Guan S. Instructor immediacy in the Chinese college classroom. Commun Stud. 1998;49(3):240–254. | ||

Park HS, Lee SA, Yun D, Kim W. The impact of instructor decision authority and verbal and nonverbal immediacy on korean student satisfaction in the US and South Korea. Commun Educ. 2009;58(2):189–212. | ||

Pelowski S, Frissell L, Cabral K, Yu T. So far but yet so close: student chat room immediacy, learning, and performance in an online course. J Interact Learning Res. 2005;16(4):395–407. | ||

Pribyl CB, Sakamoto M, Keaten JA. The relationship between nonverbal immediacy, student motivation, and perceived cognitive learning among Japanese college students. Jpn Psychol Res. 2004;46(2):73–85. | ||

Richmond VP, Gorham J, McCroskey JC. The relationship between selected immediacy behaviors and cognitive learning. In: McLaughlin M, editor. Communication yearbook 10. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1987. p. 574–590. | ||

Roberts A, Friedman D. The impact of teacher immediacy on student participation: an objective cross-disciplinary examination. Int J Teach Learn Higher Educ. 2013;25(1):38–46. | ||

Rocca KA. College student attendance: impact of instructor immediacy and verbal aggression. Brief report. Commun Educ. 2004;53(2):185–195. | ||

Rocca KA. Participation in the college classroom: the impact of instructor immediacy and verbal aggression. J Classroom Interact. 2009;43(2):22–33. | ||

Schrodt P, Witt PL. Students’ attributions of instructor credibility as a function of students’ expectations of instructional technology use and nonverbal immediacy. Commun Educ. 2006;55(1):1–20. | ||

Teven JJ, Hanson TL. The impact of teacher immediacy and perceived caring on teacher competence and trustworthiness. Commun Q. 2004;52(1):39–53. | ||

Thweatt KS, McCroskey JC. The impact of teacher immediacy and misbehaviors on teacher credibility. Commun Educ. 1998;47(4):348–358. | ||

Titsworth S. Students’ notetaking: the effects of teacher immediacy and clarity. Commun Educ. 2004;53(4):305–320. | ||

Wei F-YF, Wang KY. Students’ silent messages: can teacher verbal and nonverbal immediacy moderate student use of text messaging in class? Commun Educ. 2010;59(4):475–496. | ||

Witt PL, Kerssen-Griep J. Instructional feedback I: the interaction of facework and immediacy on students’ perceptions of instructor credibility. Commun Educ. 2011;60(1):75–94. | ||

Witt PL, Wheeless LR. An experimental study of teachers’ verbal and nonverbal immediacy and students’ affective and cognitive learning. Commun Educ. 2001;50(4):327–342. | ||

Garrott CL. The Relationship between Nonverbal Immediacy, Caring and L2 Student Learning (Spanish). Petersburg, Virginia: Virginia State University; 2002. | ||

Garrott CL. The Relationship between Nonverbal/Verbal Immediacy, Learning, and Caring by the Teacher in the L2 Spanish Classroom: Online Submission; 2005. Available from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED490540.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2014. | ||

Hargett JG, Strohkirch CS. Student perceptions of male and female instructor levels of immediacy and teacher credibility. Women Lang. 1999;22(2):46. | ||

Kearney P, Plax TG, Wendt-Wasco NJ. Teacher immediacy for affective learning in divergent college classes. Commun Q. 1985;33(1):61–74. | ||

LaRose R, Whitten P. Re-thinking instructional immediacy for web courses: a social cognitive exploration. Commun Educ. 2000;49(4):320–337. | ||

Melrose S, Bergeron K. Online graduate study of health care learners’ perceptions of instructional immediacy. Int Rev Res Open Dist Learn. 2006;7(1):1–13. | ||

Messman SJ, Jones-Corley J. Effects of communication environment, immediacy, and communication apprehension on cognitive and affective learning. Commun Monogr. 2001;68(2):184–200. | ||

Mottet TP, Parker-Raley J, Beebe SA, Cunningham C. Instructors who resist “college lite”: the neutralizing effect of instructor immediacy on students’ course-workload violations and perceptions of instructor credibility and affective learning. Commun Educ. 2007;56(2):145–167. | ||

Murphrey TP, Arnold S, Foster B, Degenhart SH. Verbal immediacy and audio/video technology use in online course delivery: what do university agricultural education students think? J Agric Educ. 2012;53(3):14–27. | ||

Orpen C. Academic motivation as a moderator of the effects of teacher immediacy on student cognitive and. Education. 1994;115(1):137. | ||

Ozmen KS. Fostering nonverbal immediacy and teacher identity through an acting course in English teacher education. Aust J Teacher Educ. 2010;35(6):1–23. | ||

Rester CH, Edwards R. Effects of sex and setting on students’ interpretation of teachers’ excessive use of immediacy. Commun Educ. 2007;56(1):34–53. | ||

Robinson RY. Affiliative communication behaviors: a comparative analysis of the interrelationships among teacher nonverbal immediacy, responsiveness, and verbal receptivity on the prediction of student learning. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association; 1995; Albuquerque, NM. | ||

Rocca KA. Participation in the college classroom: the impact of instructor immediacy and verbal aggression. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association; 2001; Atlanta, GA. | ||

Rodriguez JI, Plax TG, Kearney P. Clarifying the relationship between teacher nonverbal immediacy and student cognitive learning: affective learning as the central causal mediator. Commun Educ. 1996;45(4):293–305. | ||

Wang TR, Schrodt P. Are emotional intelligence and contagion moderators of the association between students’ perceptions of instructors’ nonverbal immediacy cues and students’ affect? Commun Rep. 2010; 23(1):26–38. | ||

Witt PL, Schrodt P. The influence of instructional technology use and teacher immediacy on student affect for teacher and course. Commun Rep. 2006;19(1):1–15. | ||

Baringer DK, McCroskey JC. Immediacy in the classroom: student immediacy. Commun Educ. 2000;49(2):178–186. | ||

Zhang Q. Immediacy, humor, power distance, and classroom communication apprehension in Chinese college classrooms. Commun Q. 2005;53(1):109–124. | ||

Teven JJ. Effects of supervisor social influence, nonverbal immediacy, and biological sex on subordinates’ perceptions of job satisfaction, liking, and supervisor credibility. Commun Q. 2007;55(2):155–177. | ||

Doohwang L, LaRose R. The impact of personalized social cues of immediacy on consumers’ information disclosure: a social cognitive approach. CyberPsychol, Behav Soc Networking. 2011;14(6):337–343. | ||

Wrench JS, Punyanunt NM. Advisee-advisor communication: an exploratory study examining interpersonal communication variables in the graduate advisee-advisor relationship. Commun Q. 2004;52(3):224–236. | ||

Erlandson K. Stay out of my space! Territoriality and nonverbal immediacy as predictors of roommate satisfaction. J Coll Univ Student Housing. 2012;38(2):46–61. | ||

Gottlieb R, Wiener M, Mehrabian A. Immediacy, discomfort-relief quotient, and content in verbalizations about positive and negative experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967;7(3):266–274. | ||

Burgoon JK, Hale JL. Nonverbal expectancy violations: model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Commun Monogr. 1988; 55(1):58–79. | ||

Sanders JA, Wiseman RL, Matz SI. The influence of gender on the uncertainty reduction strategies of disclosure, interrogation, and nonverbal immediacy. Paper presented at: The meeting of the Western Speech Communication Association; 1989; Spokane, WA. | ||

Hill CE, Gelso CJ, Chui H, et al. To be or not to be immediate with clients: the use and perceived effects of immediacy in psychodynamic/interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2014;24:299–315. | ||

Clemence AJ, Fowler JC, Gottdiener WH, et al. Microprocess examination of therapeutic immediacy during a dynamic research interview. Psychotherapy. 2012;49(3):317. | ||

Koermer C, Goldstein M, Fortson D. How supervisors communicatively convey immediacy to subordinates: an exploratory qualitative investigation. Commun Q. 1993;41(3):269–281. | ||

Ahmed SMS, Bigelow BJ. A classroom demonstration of the immediacy principle using “Dear John” letters. J Soc Psychol. 1994;134(1): 129–130. | ||

Gorham J, Cohen SH, Morris TL. Fashion in the classroom II: instructor immediacy and attire. Commun Res Rep. 1997;14(1):11–23. | ||

Lee D, LaRose R. The impact of personalized social cues of immediacy on consumers’ information disclosure: a social cognitive approach. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Networking. 2011;14(6):337–343. | ||

Kreps GL, Neuhauser L. Artificial intelligence and immediacy: designing health communication to personally engage consumers and providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(2):205–210. | ||

Stewart RA, Barraclough RA. Immediacy and enthusiasm as separate dimensions of effective college teaching: a test of Lowman’s model on student evaluation of instruction and course grades. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the Western Speech Communication Association; 1992; Boise, ID. | ||

Lee LA, Sbarra DA, Mason AE, Law RW. Attachment anxiety, verbal immediacy, and blood pressure: results from a laboratory analog study following marital separation. Pers Relatsh. 2011;18(2):285–301. | ||

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2(2). | ||

Liu Y, Malin JL, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC. Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: the role of provider, Äìpatient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):829–836. | ||

Spinewine A, Claeys C, Foulon V, Chevalier P. Approaches for improving continuity of care in medication management: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(4):403–417. | ||

Wiener M, Mehrabian A. Language within Language: Immediacy, a Channel in Verbal Communication. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1968. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.