Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 17

A Qualitative Study on Postpartum Women Experienced Various Pain Throughout the Perinatal Period Based on the Thrive Model

Received 30 August 2023

Accepted for publication 14 December 2023

Published 28 December 2023 Volume 2023:17 Pages 3577—3587

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S437901

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Jie Yang,1,2 Xue Li2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Nursing, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xue Li, Department of Nursing, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, 95 Yongan Road, Xicheng District, Beijing, 100050, People’s Republic of China, Tel +18803046093, Fax +86 1063023261, Email [email protected]

Aim: This study aims to thoroughly explore to comprehensively examine the diverse types and subjective experiences of pain in postpartum women throughout perinatal period, aiming to deepen understanding and support the development of precise pain management strategies in nursing care.

Design: A descriptive qualitative study.

Methods: Between August and November 2022, postpartum women attending outpatient clinics at a tertiary level A hospital were selected as participants. The study followed the framework of the THRIVE model and utilized a phenomenological method for qualitative research. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 21 postpartum women, and the data were analyzed using the Colaizzi 7-step analysis method.

Results: Thematic analysis revealed that different postpartum women exhibited diverse perceptions of their own pain experiences. Three themes were identified to describe the pain encountered by postpartum women: (1) Experiencing pain is complex (including experiencing multiple kinds of pain, individual differences in pain, and pain is variable), (2) Double perceptions of pain (negative effects of pain and positive energy for perceiving pain), and (3) Fighting pain requires active support (active outside support and construct a positive self-coping style).

Conclusion: This study provides a comprehensive overview of perinatal pain management in postpartum women, offering recommendations for accurate pain understanding and management. Healthcare professionals should be vigilant about maternal pain changes and individual experiences, implement targeted measures and support, aid in alleviating psychological burdens, boost maternal confidence in childbirth, and enhance postpartum quality of life.

Patient or Public Contribution: In this study, interviews were conducted in the hospital outpatient department, and the participants included in this study participated in the interviews to provide support for the implementation of this subject.

Keywords: postpartum, pain, perinatal period, qualitative study, THRIVE model

Introduction

According to the report, about 140 million women give birth every year in the global.1 While China has witnessed a significant decrease in its birth rate in recent years, the nation documented a noteworthy birth population of 9.56 million in 2022.2 Pregnant and postpartum women constitute a significant and crucial demographic within the population.3 Childbirth, as a natural physiological process specific to females, is characterized by significant stress and impacts on both the maternal body and emotional well-being.4 Regardless of whether it occurs through natural vaginal delivery or cesarean section, pain is a common symptom experienced by parturient women during this process.5 Throughout the entire parturition process, parturient women encounter diverse forms of pain, extending beyond labor-related distress. Across the gestational period, as maternal body mass incrementally rises and fetal development progresses, especially in the advanced gestational phases, heightened discomfort is noted in the lumbar and lower extremity regions.6 This encompasses discomfort in assorted joints, perineal pain stemming from vaginal lacerations during parturition, discomfort resulting from surgical lacerations, and persistent postnatal discomfort. This persistent postnatal discomfort comprises perineal discomfort, incision-related discomfort, breast discomfort, lumbar discomfort, and severe cephalalgias.7

A study highlights the heightened prevalence of perinatal pain among peripartum women, with 70% of parturients experiencing profound pain during childbirth that proves challenging to endure.8 Research elucidates that,9 antecedent to delivery, roughly 31.7% of peripartum women contend with pain or discomfort in the pubic symphysis region. The prevalence is approximately 12% in early pregnancy, escalating to about 34% in mid-pregnancy, and reaching a peak of 52% in late pregnancy.10 While the majority of acute pain resulting from physical trauma during childbirth rapidly diminishes postpartum, a subset of parturients undergoes a gradual progression of pain evolving into postpartum chronic pain.Recent survey findings from Sweden indicate that 1 in 6 women still grapple with chronic pain eight months postpartum,11 exhibiting a spectrum of pain severity from moderate to severe.The pain encountered by peripartum women may induce substantial functional impairments, potentially exerting repercussions on daily life and the mother-infant relationship.12

The pain experienced during uncontrolled childbirth may manifest as chronic persistent pain, elevating the risk of Postpartum Depression.13 The distress endured throughout the entire labor process not only adversely affects the physical and mental well-being of peripartum women but also detrimentally impacts the quality of family life and the health trajectory of subsequent generations.14 Consequently, meticulous attention to pain occurrence throughout the perinatal period is imperative for peripartum women. A nuanced understanding of the diverse spectrum of pains associated with childbirth is pivotal in fostering heightened awareness among healthcare professionals and family members. This awareness, coupled with proactive pain management strategies during the childbirth cycle, aims to mitigate pain and ensure the safety and well-being of both mother and infant.

However, current research predominantly focuses on exploring parturient pain during childbirth,15–17 with insufficient attention to a comprehensive study of pain management throughout the entire perinatal continuum, encompassing the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum phases. While some studies have delved into the quantitative assessment of maternal pain levels and influencing factors, they often lack a qualitative exploration of the diverse experiences and perceptions of pain among women during the perinatal period.

Due to the hospital’s recruitment policy, postpartum examinations are required 42 days after childbirth. We deliberately selected postpartum women for a follow-up examination at the hospital after 42 days.In accordance with this definition, we specifically selected women who completed the entire perinatal continuum for inclusion in this study. Employing the phenomenological approach combined with the THRIVE model involves six consecutive steps:18 Taking stock, Harvesting hope, Re-authoring, Identifying change, Valuing change, and Expressing change in action. This selection aims to gain in-depth insights into the types and perceptions of pain experienced throughout the entire childbirth process, further exploring the impact of pain on these women and their specific needs in pain management. Hence, our research endeavors to furnish valuable insights for formulating specific and all-encompassing strategies in pain management.

It seeks to deepen comprehension of pain experienced by women across various stages of childbirth, ultimately aiming to enhance self-efficacy and elevate the quality of life in the context of maternal pain management.

Methods

Design

This research is a qualitative exploratory descriptive study.19 We used semi-structured interviews, applied phenomenological research methods and Colaizzi’s Seven-step method.20 This study interviewed postpartum women who experienced perinatal pain feelings and experiences. This study meets the uniform criteria of Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).21

Setting and Participants

The study recruited eligible postpartum women from the outpatient clinic of a tertiary Grade A hospital in Beijing, China, from August to November 2022.The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Successful completion of childbirth; (2) More than 4 weeks after delivery, through the perinatal period;22 (3) Without any mental illness and able to communicate smoothly; (4) Volunteer to participate in this study. Objective sampling method was used for voluntary participation. In order to determine the number of postpartum women in the sample, data saturation was considered in the qualitative research until no new interview content appeared.23 Finally, it was determined that 21 postpartum women were required to reach data saturation.

Ethical Consideration

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (IRB number:2023-P2-126-01). All subjects provided their informed consent, both verbally and in writing, after receiving detailed information about the study’s objectives and procedures. Informed consent was duly acquired from all participants.We adhere to the principle of confidentiality when collecting information and collating information about participants.All maternal information will be anonymized using codes during the process of transcription, and recordings and interviews will be kept confidential.

Data Collection

Our study takes THRIVE model as the framework and forms a rough interview outline based on reference to relevant literature.24,25 To adjust the interview content, it was revised by a nursing team with qualitative methodological expertise. Then, 4 postpartum women were selected for pre-interview, and the interview outline was revised according to the interview results and expert opinions, and finally the interview outline was determined. The final interview outline consists of five open-ended questions to explore the experience and feelings of perinatal pain:

- What kinds of pain did you experience throughout the perinatal period ?

- Which pains are most impressive to you? Why is that?(c) How do you deal with these pains?(d) How does pain affect you?(e) What kind of help do you want when facing pain? (f) If faced with such pain again, how would you cope with the change?

During the interview, keep a relaxed atmosphere, and each interview lasts for 30–60 minutes. At the same time, the interview skills such as questioning, listening, answering and repeating were used, and the movements, body language and expression changes of the interviewees were observed and recorded.

Data Analysis

The recording of this interview was transcribed within 24 hours of the interview. We used CoIaizzi’s seven-step analysis method to analyze and organize the interview data:19 (1) the researchers copied the interview records verbatim into text, and were generally familiar with the description content of the participants; (2) The researchers summarized and analyzed the data to refine the important statements; (3) Encode the extracted important and repeated ideas. (4) Researchers classify and refine the encoded ideas to form sub-themes and themes.(5) A complete description of the relationship between the research topic and the research phenomenon; (6) Elaborate and analyze each theme and content; (7) The interview results will be returned to the respondents for confirmation to ensure the accuracy of the research.

Trust Worthiness

We considered to establish the credibility, transferability, dependability.26 The credibility was reflected in the fact that we chose to interview women of different ages, modes of delivery, education levels and economic levels to ensure that the data covered all significant changes. Reliability was achieved by training and learning researchers in uniform qualitative interview skills, promoting the quality of the data analysis process, and making consistent decisions through group discussions. In the meanwhile, we ensure the transferability of data by providing an accurate description of culture and context, characteristics of participants, data collection and process.

Results

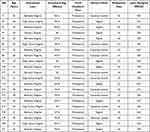

A total of 21 postpartum women were participated in this study. Their age ranged from 24 to 42 years, with an average age of (33.09±3.948) years. Additional details of the participants are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 The Details of the Participants |

Our research interview outline and data analysis are guided by the THRIVE model (Figure 1).The following section introduces the themes and subthemes and the related quotes of this study. And the symbols (P1-P21) are used to indicate the interview from which the quotations originated.

|

Figure 1 The relational diagram distilled by THRIVE on the interview topics for this study. Note: Bold text represents the themes extracted in this study. |

Experiencing Pain is Complex

Experiencing Multiple Kinds of Pain

All the participants reported experiencing multiple pains throughout the birth cycle. There are different types and sensations of pain before, during and after delivery.

Pre-Delivery

Early in my pregnancy, I had a burning sensation in my stomach. By the end of my pregnancy, I was aching all over. (P3)

After 12 weeks of pregnancy, my tail vertebrae started to hurt, and the pain got worse and continued into the third trimester. (P5)

My pubic bone hurt before delivery, and it gets worse when I stand for a long time, or when I make huge movements. It’s a feeling of bone dislocation, and it becomes so severe that it affects getting out of bed and turning over in bed. (P19)

At the beginning of my pregnancy, I had lower back pain. After three months of pregnancy, my lower back pain got worse and I had to be supported by my husband to get up from bed. (P21)

I took the subway a lot, and the pain in the balls of my feet was noticeable in the third trimester. (P11)

During Delivery

Different types of labor bring different kinds of pain during labor. For women who have undergone vaginal delivery, contraction pain is the main type of pain. For C-section women, they feel the pain of surgery and anesthesia.

When I was in the delivery room, the contractions were painful for about three hours, and I almost lost consciousness. (P2)

Every time the contractions came, it was painful. My whole body felt like a convulsion, and after the oxytocin injection, it hurt even more. (P16)

When I was giving birth, the worst pain was the pain of the anesthetic injection. (P6)

It was a special pain in the anesthetic, which was a kind of boring pain, mainly an unknown fear that would make me feel more pain. (P19)

After Delivery

After delivery, different delivery methods have different postpartum pain, but there are also the same kinds of pain.

First of all, different types of pain occur in various joints of the body.

My whole back hurts after I gave birth, and it gets worse when I stand for a long time. My wrists also hurt when I get up in the morning, especially when my hands get cold water. (P3)

After delivery, I had lower back pain whenever I held the baby. Sometimes lying in bed to feed, a long-term position, side of the body will be cervical spine pain, there is a feeling of stiff neck. (P6)

After I gave birth, I started to have leg and knee pain, which I didn’t have before. When you walk, it gets worse. (P16)

When I am breastfeeding, my baby has a pinprick sensation when sucking because my nipples are sunken, and then the baby bites the nipple and wears the underwear with friction. (P1)

After I gave birth, my hand joints were very swollen. I felt stiff in the morning when I got up, and my hand joints would hurt if I kept holding the baby. And if I walk too much, I felt discomfort in my groin and pain in my hipbone. (P10)

Most postpartum women have mentioned that breastfeeding brings different pain feelings.

Every time I breast-feed, it causes my contractions to hurt, especially when I first start feeding. (P6)

My baby bites the skin on my nipples, causing chapped nipples. Every time I feed, I feel a sharp pain that I have never felt before. (P11)

Because my nipples are sunken, the first time I breastfed the nipple to suck out, I feel particularly painful. Then my baby bit the nipple and I got mastitis twice. Every time I breastfed, it was very painful. (P13)

In addition, some participants reported different types of pain.

There was side cutting during labor, and I could feel someone with scissors frying my meat. When the anesthetic wore off, I felt more pain in the side cut. I have been home for half a month, and I can still feel the stretch of the side cut. (P10)

The worst pain was when I came back from the surgery and the nurse pressed on my stomach to check the uterine contractions. It was very painful. Every time I was pressed, I felt like I was dying from the pain. (P7)

After the operation, it was difficult to urinate. Because I drank less water, I could not urinate at the beginning, resulting in a painful bladder. After coming home from the hospital, my hemorrhoids became more serious, which caused a lot of pain. (P15)

Because of the lateral cut wound in the perineum, I still felt pain after I resumed my marital sex life, which also affected my mood. (P21)

Individual Differences in Pain

For the pain of contractions during childbirth, different maternal feelings have individual differences.

I went through labor very quickly, with contractions averaging every two minutes. I felt more pain than anyone else, like someone had punched me in the stomach, but I felt good and I could stand it. (P4)

When the contractions happen, I feel like I have a pain in my back, not in my front stomach, like a cold spasm. (P5)

When I experienced the contractions, the pain was a severe pain that I couldn’t control, which made me unable to control my breathing. (P18)

I feel like I haven’t experienced too much pain throughout the pregnancy, and I only have a little pain during contractions, like menstruation, not very uncomfortable (P20)

When it came to the most impressive pain in the whole perinatal period, the responses were inconsistent.

When I was doing amniotic fluid puncture, because I didn’t do it before, I was psychologically afraid and felt more sensitive to pain, so it was very impressive to me. (P6)

When I was eight months pregnant, my pubic bone was separated, and I couldn’t walk at all. My whole hip pain hurts, which is hard to forget during pregnancy. (P21)

Pain is Variable

Participants reported that the pain they felt was changing as the pregnancy progressed.

I didn’t feel much before I went into labor, but by the time I went into labor, the contractions were hurting for about three hours and I almost lost consciousness. (P2)

I didn’t feel anything before the birth, I was in pain for a whole day when the contractions came, and the pain when the uterine opening was unbearable. When I finally gave birth to the biggest feeling is relaxed, not too much pain. (P13)

Double Perceptions of Pain

Negative Effects of Pain

Some participants revealed a negative impact on their life after childbirth and were more cautious about their future fertility choices after experiencing pain during childbirth.

I was in so much pain that I didn’t really want to have a second child. I didn’t want to repeat the pain myself. (P21)

When I was breastfeeding, I felt like a cow. My family just asked me to feed the baby at the right time and never felt how I felt. Every time I feed my child, I have a gut-wrenching pain, which others can't understand. My husband cares more about the children and ignores my pain. (P9)

Because I have rheumatism, I can't stop the pain during the operation. After the surgery, I experienced a lot of pain. I really want to have a second child, but I don’t want to have another child once I feel so painful. The pain has caused me a psychological shadow. (P19)

I had three babies by cesarean section. I haven’t used a pain-relief pump before, but this time I used a pain-relief pump, and it was very effective. After the surgery, the pain relief is also less painful when you get out of bed and walk around. (P8)

Positive Energy for Perceiving Pain

When it comes to the impact of pain, some participants also indicated that pain can be transformed into a positive force by applying a positive attitude to the perception of pain.

My labor was progressing quickly, and when I got to the bed, I felt the pain was helping. The midwife taught me how to control my strength, and I felt the pain helping me see the baby as soon as possible. (P4)

I think the pain is inevitable. Whenever the contractions hurt so much, I think it was worth it to go through the pain and see my baby born. (P18)

Fighting Pain Requires Active Support

Active Outside Support

In the face of pain, the majority of participants reported the need for positive external support, which was an important factor in their pain relief.

Doula’s help is effective when you are expecting. When I was breathless from contractions, Doula guided me carefully and taught me to relax and take deep breaths, which relieved my pain and tension. (P4)

During the prenatal period, I participated in the pregnant women’s class held by the hospital and learned a lot of knowledge about childbirth, so I was confident about many links in the process of childbirth. I also practice yoga for a long time, which makes me more sensitive to changes in my body, so I can get along with pain more peacefully. (P4)

I had three babies by cesarean section. I haven’t used a pain-relief pump before, but this time I used a pain-relief pump, and it was very effective. After the surgery, the pain relief is also less painful when you get out of bed and walk around. (P6)

Construct a Positive Self-Coping Style

I didn’t feel much pain throughout the pregnancy. I think I adjusted my mind pretty well. If I encountered difficulties, I accepted them and tried to solve them, so I didn’t feel like I experienced too much pain. (P12)

In general, I think my own tolerance to pain is relatively high. Because the pain can only be borne and experienced by myself, and my family can't bear it for me, so I have to be mentally prepared to face it positively. (P14)

Discussion

Childbirth is a normal physiological phenomenon and an important period in the whole gestation process.27 The pain of childbirth is a complex psychological process for parturient women, which has a strong emotional color and is a process of psychological stress.28 Throughout the perinatal period, postpartum women experience more than painful contractions.A variety of physical discomfort in the prenatal, postpartum pain will also make the mother troubled.29 First of all, pregnant women face the most pain in the prenatal period is due to the stomach discomfort caused by morning sickness, and as the month progresses, the pain in the waist and crotch. Different types of labor bring different kinds of pain during labor. Because everyone interprets pain differently, the pain response caused by a contraction of the same intensity will feel differently for each output. The types of postpartum pain mainly involve uterine contraction pain, perineal incision pain, abdominal wound pain, breast tenderness and postpartum joint pain of various parts of the body. Therefore, pain experienced by pregnant women during the perinatal period is multifaceted, with the majority of individuals encountering at least three distinct types of pain. Furthermore, the nature and intensity of this pain exhibit dynamic fluctuations over time.

Many kinds of pain experienced in the process of childbirth not only make maternal mental tension and fear, but also cause stress response, resulting in maternal self-efficacy decline.30 Whether experiencing vaginal delivery or cesarean section, parturient women are affected by different pain, which produce negative emotions of fear, worry and anxiety, and these negative emotions make the pain threshold of parturient women decrease again and aggravate the sense of pain.31 Studies have shown that about 70% of women experience unbearably intense pain during childbirth,32 which can be so painful that they are unable to live. The severity of postpartum acute pain may increase the risk of postpartum chronic pain and postpartum depression. Our study also found that women with more severe postpartum pain showed more negative emotions in self-reporting, which is consistent with the results of previous studies. In addition, previous studies have found that women who delivered by cesarean section had lower expectations of labor pain than they actually experienced.33 Therefore, We should promote pregnant women to have a certain understanding of postoperative pain and more adequate psychological preparation, so as to correctly understand the impact of cesarean section and natural delivery on body and mind. However, due to the physiologic nature of labor pain, it is often ignored by midwifery staff, resulting in insufficient attention to labor pain. In the postpartum, the family of the maternal pain is not enough attention, resulting in an increased incidence of postpartum depression. Thus, maternal pain management has not been given due attention. In the face of different types of pain emotional changes did not receive timely support, lack of perfect analgesia program. Therefore, medical staff and family members should pay attention to the pain of postpartum women in different stages, timely understand the degree, location, frequency and intensity of pain, give corresponding management measures, strengthen psychological support and emotional counseling for postpartum women.

The lack of understanding of the pain of childbirth makes the postpartum women produce fear, tension and other psychological, these negative psychological can cause the pain of postpartum women to escalate again.34 However, pain has a dual role. The positive role of pain in childbirth can effectively help pregnant women cope with it positively. Our study also confirms the findings of previous researchers that changing the negative perception of pain and creating a positive feeling of pain can help postpartum women during labor. Therefore, it is especially important to make positive pain knowledge in postpartum women. We should conduct a pain knowledge education before childbirth, which leads the woman to understand the various pains of childbirth, and to create the positive ability of the pregnant woman to feel positive about pain. In addition, strengthening pain education can make pregnant women better understand the occurrence mechanism and characteristics of pain related to childbirth, as well as methods and techniques to reduce pain, and help them have a deeper understanding of pain, which can effectively promote better coping.

Pregnant women with stronger internal and external support had higher self-efficacy in coping with pain. First of all, there are drug analgesic techniques and non-drug analgesic methods to relieve labor pain.35 Among them, drug analgesia technology can reduce the maternal body pain, and reduce the incidence of postpartum depression.36 But in the choice of drug analgesia technology, to combine with the maternal physical condition to choose the appropriate method.Our study also found that some parturient women in the application of analgesic pump is a great effect. However, we strongly recommend the use of non-drug analgesic techniques in clinical practice, which is the safest method for the labor process and the fetus. There are a variety of non-drug analgesia methods, including psychological support therapy, doula accompany, Lamaze breathing pain reduction method, music therapy, acupressure, exercise, active family support and so on.37,38

Compared with drug analgesia, non-drug analgesia pays more attention to the psychological and emotional changes of pregnant women and is a commonly used analgesia technique advocated by the World Health Organization.35 However, at present, the application rate of non-drug labor pain technique is not optimistic.39 The study found that expectant pregnant women have a high demand for doula during childbirth.40 Our study also confirmed that women who used doula reported that doula reduced pain and improved their ability to respond positively to childbirth. To increase the positive social support for pregnant women, family members should provide material and spiritual support and encouragement,41 can effectively promote the establishment and improvement of self-efficacy of pregnant women, so that they can better cope with the process of childbirth. Therefore, the external support of family members plays an important role. Our study also found that the majority of mothers expressed a desire for a more palatable and rich diet from their families, as well as companionship from their spouses.

Conclusion

Our research add to the experience of various kinds of pain experienced by postpartum women in the whole perinatal period. The pain experienced by postpartum women is not homogeneous but rather exhibits dynamic and evolving characteristics. Additionally, the focal points of pain experienced by postpartum women are individualized. By investigating the diverse subjective experiences of pain before, during, and after delivery, we can gain insights into their pain management requirements. As healthcare professionals, it is crucial for us to remain attentive to the evolving nature of pain and its management during the perinatal period. Timely dissemination of pertinent knowledge to pregnant women, along with emotional support and encouragement from their families, can enhance women’s delivery experiences and foster increased confidence in childbirth.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all postpartum women for sharing their experiences, as well as the help and support of nursing staff during the data collection process.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

1. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–980.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1

2. Su Y, Lu Y, Li W, et al. Prevalence and correlation of metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study of nearly 10 million multi-ethnic Chinese adults. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4869–4883. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S278346

3. Fan SL, Xiao CN, Zhang YK, Li YL, Wang XL, Wang L. How does the two-child policy affect the sex ratio at birth in China? A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):789. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08799-y

4. Antoine C, Young BK. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920–2020: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Perinat Med. 2020;49(1):5–16. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0305

5. Brito APA, Caldeira CF, Salvetti MG. Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of pain during the postpartum period. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2021;55:e03691. doi:10.1590/S1980-220X2019023303691

6. da Mota PGF, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, K B. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Man Ther. 2015;20(1):200–205. doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002

7. Cardaillac C, Vieillefosse S, Oppenheimer A, Joueidi Y, Thubert T, Deffieux X. Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles in postpartum: concordance of patient and clinician evaluations, prevalence, associated pelvic floor symptoms and quality of life. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:228–232. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.038

8. Deepak D, Kumari A, Mohanty R, Prakash J, Kumar T, Priye S. Effects of epidural analgesia on labor pain and course of labor in primigravid parturients: a prospective non-randomized comparative study. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e26090. doi:10.7759/cureus.26090

9. Nanji JA, Carvalho B. Pain management during labor and vaginal birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;67:100–112. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.03.002

10. Wiezer M, Hage-Fransen MAH, Otto A, et al. Risk factors for pelvic girdle pain postpartum and pregnancy related low back pain postpartum; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102154. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102154

11. Molin B, Sand A, Berger AK, Georgsson S. Raising awareness about chronic pain and dyspareunia among women - A Swedish survey 8 months after childbirth. Scand J Pain. 2020;20(3):565–574. doi:10.1515/sjpain-2019-0163

12. Shebelsky R, Sadi W, Heesen P, et al. The relationship between postpartum pain and mother-infant bonding: a prospective observational study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2023:101315. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101315

13. Lim G, Levine MD, Mascha EJ, Wasan AD. Labor pain, analgesia, and postpartum depression: are we asking the right questions? Anesth Analg. 2020;130(3):610–614. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004581

14. Bijl RC, Freeman LM, Weijenborg PT, Middeldorp JM, Dahan A, van Dorp EL. A retrospective study on persistent pain after childbirth in the Netherlands. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1–8. doi:10.2147/JPR.S96850

15. Schnabel K, Drusenbaum AM, Kranke P, Meybohm P, Wöckel A, Schnabel A. Determinants of satisfaction with acute pain therapy during and after childbirth. Anaesthesiologie. 2023;72(5):325–331. doi:10.1007/s00101-023-01260-w

16. van H-T, Haken TM, Hendrix MJ, Nieuwenhuijze MJ, de Vries RG. Birth place preferences and women’s expectations and experiences regarding duration and pain of labor. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;39(1):19–28. doi:10.1080/0167482X.2017.1285900

17. Joensuu J, Saarijärvi H, Rouhe H, et al. Maternal childbirth experience and pain relief methods: a retrospective 7-year cohort study of 85 488 parturients in Finland. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e061186. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061186

18. White K, Issac MS, Kamoun C, Leygues J, Cohn S. The THRIVE model: a framework and review of internal and external predictors of coping with chronic illness. Health Psychol Open. 2018;5(2):2055102918793552. doi:10.1177/2055102918793552

19. Chesser-Smyth PA. The lived experiences of general student nurses on their first clinical placement: a phenomenological study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2005;5(6):320–327. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2005.04.001

20. Burns M, Peacock S. Interpretive phenomenological methodologists in nursing: a critical analysis and comparison. Nurs Inq. 2019;26(2):e12280. doi:10.1111/nin.12280

21. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

22. Dickstein Y, Ohel I, Levy A, Holcberg G, Sheiner E. Lack of prenatal care: an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality among macrosomic newborns. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277(6):511–514. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0510-6

23. Mei YX, Lin B, Zhang W, et al. Benefits finding among Chinese family caregivers of stroke survivors: a qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e038344. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038344

24. Xiong PT, Poehlmann J, Stowe Z, Antony KM. Anxiety, depression, and pain in the perinatal period: a review for obstetric care providers. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2021;76(11):692–713. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000958

25. Flick RP, Hebl JR. Pain management in the perinatal period. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40(3):xvii–xviii. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2013.05.016

26. Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

27. Çankaya S, Şimşek B. Effects of antenatal education on fear of birth, depression, anxiety, childbirth self-efficacy, and mode of delivery in primiparous pregnant women: a prospective randomized controlled study. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(6):818–829. doi:10.1177/1054773820916984

28. Annborn A, Finnbogadóttir HR. Obstetric violence a qualitative interview study. Midwifery. 2022;105:103212. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103212

29. Majorie Ensayan AJ, Cheah WL, Helmy H. Postpartum health of working mothers: a prospective study. Malays Fam Physician. 2023;18:48–100. doi:10.51866/oa.167

30. Havizari S, Ghanbari-Homaie S, Eyvazzadeh O, Mirghafourvand M. Childbirth experience, maternal functioning and mental health: how are they related? J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2022;40(4):399–411. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1913488

31. Poehlmann JR, Stowe ZN, Godecker A, Xiong PT, Broman AT, Antony KM. The impact of preexisting maternal anxiety on pain and opioid use following cesarean delivery: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4(3):100576. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100576

32. Vignato J, Beck CT, Conley V, Inman M, Patsais M, Segre LS. The lived experience of pain and depression symptoms during pregnancy. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2021;46(4):198–204. doi:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000724

33. Bjørnstad J, Ræder J. Post-operative pain after caesarean section. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2020;140(7). doi:10.4045/tidsskr.19.0506

34. Jonsdottir SS, Steingrimsdottir T, Thome M, et al. Pain management and medical interventions during childbirth among perinatal distressed women and women dissatisfied in their partner relationship: a prospective cohort study. Midwifery. 2019;69:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.018

35. Gallo RBS, Santana LS, Marcolin AC, Duarte G, Quintana SM. Sequential application of non-pharmacological interventions reduces the severity of labour pain, delays use of pharmacological analgesia, and improves some obstetric outcomes: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2018;64(1):33–40. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2017.11.014

36. Kinugasa M, Miyake M, Tamai H, Tamura M. Safety and efficacy of a combination of pethidine and levallorphan for pain relief during labor: an observational study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45(2):337–344. doi:10.1111/jog.13850

37. Haakstad LA, K B. Effect of a regular exercise programme on pelvic girdle and low back pain in previously inactive pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(3):229–234. doi:10.2340/16501977-1906

38. Cai Y, Shen Z, Zhou B, et al. Psychological status during the second pregnancy and its influencing factors. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2355–2363. doi:10.2147/PPA.S374628

39. Konlan KD, Afaya A, Mensah E, Suuk AN, Kombat DI. Non-pharmacological interventions of pain management used during labour; an exploratory descriptive qualitative study of puerperal women in adidome government hospital of the volta region, Ghana. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):86. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01141-8

40. Ravangard R, Basiri A, Sajjadnia Z, Shokrpour N. Comparison of the effects of using physiological methods and accompanying a doula in deliveries on nulliparous women’s anxiety and pain: a case study in Iran. Health Care Manag. 2017;36(4):372–379. doi:10.1097/HCM.0000000000000188

41. Bedaso A, Adams J, Peng W, Sibbritt D. The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):162. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01209-5

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.