Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 16

A Case of Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Misdiagnosed with Keloid

Received 3 March 2023

Accepted for publication 5 May 2023

Published 12 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1243—1248

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S409182

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Anne-Claire Fougerousse

Di Kong, Danqi Deng

Department of Dermatology, Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, Yunnan, 650101, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Danqi Deng, Fax +86-871-65351214, Email [email protected]

Abstract: We report a case of a patient initially diagnosed with keloid and eventually diagnosed by skin histopathology and immunohistochemistry with primary cutaneous ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Keywords: primary cutaneous ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma, keloid, misdiagnosis

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)is a subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, first reported by Stein et al in 1985, and is usually seen in children and young adults, accounting for 10–15% of paediatric NHL and only 2% of adult NHL.1 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pC-ALCL) is a subtype of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. pC-ALCL is a CD30-positive proliferative disease of cutaneous lymphoid tissue with large tumour cells that have a pleomorphic, mesenchymal or immunoblast cell pattern. The etiology and pathogenesis of pC-ALCL is unclear and may be genetically and immunologically related, and often requires clinical differentiation from lymphomatoid papulosis, systemic ALCL, transforming mycosis fungoides and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Here, we report a case of an initial misdiagnosis with keloid, corrected diagnosis with pC-ALCL and successfully treated with CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone).

Case Report

A 58-year-old male presented with a red papule on the lateral side of his left knee 6 months ago with no apparent cause, after which the papule gradually increased in size to 2*3 cm (Figure 1) and was seen at an outside hospital, where he was diagnosed with “keloid”. “Compound Betamethasone injection 1mL topical injection” once a month for 4 times, Subsequently, the lesion increased in size to 7*8 cm irregular plaque, with ulceration and crusting on the surface, several small papules appear in the periphery (Figure 2). The patient presented to our hospital in May 2022 and he underwent a general examination and skin biopsy.

|

Figure 1 Clinical photograph of the patient: Initial photograph of the patient. |

|

Figure 2 Clinical photograph of the patient: after topical injections of compound betamethasone injections 1 mL x 4 times. |

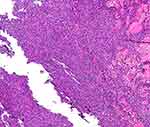

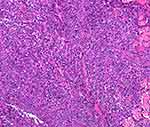

Histopathology of the lesions (Figures 3 and 4) showed the following: diffuse infiltration of tumour cells in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, partly interspersed among collagen fibres and focal infiltration of surrounding lymphocytes and large-sized tumour cells that were rich in cytoplasm, with round or irregular nuclei, obvious nucleoli, obvious heterotypes, and obvious interstitial phenomenon.

|

Figure 4 Histopathology of skin lesions: with large tumour cells, abundant cytoplasm, round or irregular nuclei, obvious nucleoli, obvious heterotypes, obvious interstitial phenomenon (HEx200). |

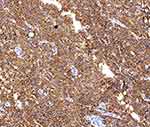

The immunohistochemistry results were as follows (Figures 5 and 6): CD30 (+++), CD3 (+), CD4 (+), CD8 (+), CD56 (-), ALK (-), CD20 (-), and Ki-67 90% or more.

|

Figure 5 Mmunohistochemistry: CD30 (+++)(IHC x100). |

|

Figure 6 Mmunohistochemistry: CD30 (+++) (IHC x200). |

PET-CT showed limited skin thickening and soft tissue mass formation with increased metabolism on the outer portion of the left knee, consistent with lymphoma, and increased metabolism in the bilateral inguinal lymph nodes; bone marrow cell morphology showed granular, red, and meganuclear triplet proliferative bone marrow; and the final diagnosis was primary cutaneous ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Six rounds of chemotherapy with the CHOP regimen were administered in June 2022, and the lesions gradually subsided (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7 Clinical photograph of the patient: After 6 rounds of chemotherapy with the CHOP regimen. |

Discussion

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) that accounts for approximately 2% of all lymphoma tumours,1 it occurs more frequently in adult males and often presents as limited purple papules, nodules, and plaques, often indicating shallow ulcers, either solitary or multiple. Depending on the site of origin, these lesions can be classified as systemic ALCL, primary cutaneous ALCL (pC-ALCL) and breast implant-associated ALCL (BIA-ALCL).2 In this case, the patient had no other systemic involvement and was ALK-negative. The patient was typed as a primary cutaneous ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma. The pathology is characterized by large tumour cells with abundant cytoplasm, round or irregular nuclei, distinct nucleoli, and pleomorphic cells. pC-ALCL usually does not express mesenchymal lymphoma kinase (ALK) and has a good prognosis, but a few patients have a poor prognosis, which may be related to ALK rearrangement, ALK-1 protein expression, ageing and immune degeneration.3 The first-line treatment for ALCL is chemotherapy with the CHOP regimen, with an overall survival rate of approximately 70%-90%.4 For patients with systemic ALCL, autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), the brentuximab vedotin (BV) regimen, etc., are available.5,6

Keloids are benign skin tumours caused by excessive proliferation of connective tissue within the skin that are secondary to a skin injury, and they typically present as a solitary or crabfoot-like irregular scars. The patient had no history of local skin trauma or scratching and no family history of keloids, and the lesion showed a single irregular scar-like appearance with scattered red papules and nodules around the plaque. The first physician did not fully consider extracutaneous disease when he saw the patient, lacked a deep understanding of the clinical manifestations of ALCL, and did not perform histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations in a timely manner. The doctor diagnosed keloid based on clinical presentation only, which led to misdiagnosis of the patient. The diagnosis of pC-ALCL was finally confirmed by histopathological examination of skin lesions and immunohistochemistry, and the disease was successfully treated.

Conclusion

Keloid scars are more common in clinical practice, and radiotherapy with X-ray or glucocorticoid intradermal injections are preferred with remarkable efficacy, which can cause misdiagnosis and omission in a small number of patients. Since scattered erythema and papules around keloids are less common, the presence of other diseases needs to be considered when erythema and papules are present around keloids, and also reminds us of the importance of timely dermatopathological tissue biopsy and immunohistochemical examination. Dermatology alone is a broad and systematic secondary clinical discipline, and many times it is difficult to accurately determine various extradermal diseases even if there are characteristic skin lesions, and a comprehensive examination can help find objective evidence. In addition, clinicians should continue to accumulate experience, think beyond the limitations of clinical thinking, and consider some rare diseases and extradermal diseases in addition to common and multiple diseases when receiving patients with primary skin lesions to effectively reduce the rate of misdiagnosis and omission and help patients to be diagnosed and treated early.

Ethics Statement

Ethical committee approval was not required for this case report.

Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to have the case details and associated images published. Institutional approval was not required.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patient.

Funding

This article has no funding support.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Abdul Rahman SA, Loutfi K, Turk T, et al. A challenging case of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma in a 12-year-old boy: a rare case report from Syria. Ann Med Surg. 2022;79:104085.

2. Wang HY, Thorson JA, Hinds BR, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma arising in a patient with multiple rounds of breast implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48(5):659–662.

3. Zhang Y, Chen M, Yu Y, et al. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with DUSP22-IRF4 rearrangement following insect bites. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49(2):187–190. doi:10.1111/cup.14147

4. Abe H, Nakamura T, Yoshitomi M, et al. The usefulness of straight chemotherapy for dermal exposed anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with intracranial invasion. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019;14(4):1218–1221. doi:10.4103/ajns.AJNS_158_19

5. Donato EM, Fernández-Zarzoso M, Hueso JA, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: an evidence-based review. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:4583–4590. doi:10.2147/OTT.S141053

6. Koh Y. Extended use of brentuximab vedotin before autologous stem-cell transplantation would benefit refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(5):798–801. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1461

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.