Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 13

Which GOLD B patients progress to GOLD D with the new classification?

Authors Choi HS , Na JO , Lee JD, Shin KC , Rhee CK, Hwang YI , Lim SY , Yoo KH , Jung KS, Park YB

Received 22 June 2018

Accepted for publication 22 August 2018

Published 12 October 2018 Volume 2018:13 Pages 3233—3241

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S177944

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Hye Sook Choi,1 Ju Ock Na,2 Jong Deog Lee,3 Kyeong-Cheol Shin,4 Chin Kook Rhee,5 Yong Il Hwang,6 Seong Yong Lim,7 Kwang Ha Yoo,8 Ki Suck Jung,6 Yong Bum Park9

1Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyunghee University Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan-si, Republic of Korea; 3Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Republic of Korea; 4Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University Hospital, Daegu, Republic of Korea; 5Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 6Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Republic of Korea; 7Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 8Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 9Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Background: The 2017 GOLD guidelines revised assessment of COPD by eliminating the FEV1 criterion.

Aim: First, we explored the redistribution of 2011 GOLD groups by reference to the 2017 GOLD criteria. Second, we investigated the characteristics of GOLD B patients and the natural course of GOLD B patients according to the 2017 GOLD guidelines.

Methods: In total, 2,010 COPD patients in the Korean COPD Subgroup Study cohort were analyzed at baseline and 1 year after enrollment.

Results: The 2011 GOLD C patients were redistributed to the 2017 A (64.5%) and C (35.4%) groups. The 2011 GOLD D patients were redistributed to the 2017 B (61.6%) and D (38.6%) groups. The GOLD B patients constituted 62.7% of all patients according to the 2017 classification. Such patients exhibited higher % predicted FEV1 values, longer six-minute walk distances, fewer symptoms, and lower inflammatory marker levels than GOLD D patients. Most GOLD B patients remained in that group (69.1%), but 13.8% progressed to group D at 1-year follow-up. The factors associated with progression from GOLD B to GOLD D were older age, higher modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) symptom scores, and a lower % predicted FEV1 value.

Conclusion: Severe symptoms, poorer health status, and greater airflow limitation increased patients’ risk of exacerbation and progression from group B to group D when the 2017 GOLD criteria were applied.

Keywords: COPD, GOLD B, progression

Plain language summary

It is important to understand the heterogeneous nature of GOLD B patient outcomes, because the majority of COPD patients are categorized as GOLD B. GOLD B patients according to the 2017 GOLD guidelines were at higher risk of exacerbations if they were older, had higher modified Medical Research Council and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire symptom scores, and a lower FEV1. Even though revised GOLD guidelines omitted FEV1 to assess COPD, FEV1 is an important factor to predict the outcomes.

Introduction

COPD patients exhibit heterogeneous features and different outcomes.1 In the natural course of COPD, some patients remain in the same disease category, while some improve and others exhibit progression to more severe categories during follow-up.2,3 To treat patients effectively, it is important to identify factors associated with disease progression.

In the ECLIPSE cohort,2 COPD patients were categorized as GOLD A, B, C, or D groups using the 2011 GOLD guidelines.4 The most common category was GOLD D (40%); GOLD B contained 14% of all COPD patients at baseline. After 3 years, 36% of the GOLD B patients remained in the GOLD B group, but 35% progressed to GOLD D. In the COPDMAP cohort,3 COPD patients were categorized as GOLD A, B, C, or D using the 2011 GOLD guidelines.4 The most common category was GOLD D (59%); GOLD B contained 29% of the COPD patients at baseline. After 1 year, 68% of the GOLD B patients remained in the GOLD B group but 25% deteriorated to GOLD D.

Recently, the GOLD guidelines have been revised; COPD assessment now features analysis of respiratory symptoms and exacerbations alone, and not the FEV1, when assigning patients to various categories.1 In the 2011 GOLD criteria,4 GOLD B patients were defined by mild-to-moderate COPD (FEV1 ≥50%), exacerbation rate <2/year, and a high symptom burden; cases with FEV1 values <50% exhibiting the same exacerbation rate and symptoms were categorized as GOLD D. According to the revised 2017 GOLD criteria,1 the former patients are categorized as GOLD B; however, the latter are categorized as GOLD B and not GOLD D. Patients with the same severe symptoms are now divided into GOLD B or D patients in terms of exacerbation risk, without reference to the FEV1. Identification of the characteristics of GOLD B and D patients, and of factors related to the progression from group B to group D, will help to clarify the exacerbation risk.

Most COPD patients in various populations are categorized as GOLD B.5 Thus, knowledge of disease development over time in GOLD B patients is important. To date, the characteristics and natural course of GOLD B patients using the 2017 GOLD assessment criteria have not been described, and this is the aim of the present study. First, we examined the GOLD category changes from 2011 to 2017; second, we identified the baseline characteristics of 2017 GOLD B patients compared to those of GOLD D patients; and third, we identified the characteristics of GOLD B patients who remained GOLD B or progressed to GOLD D within 1 year.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

All patients were selected from the Korean COPD Subgroup Study (KOCOSS) (NCT02800499) cohort between December 2011 and July 2017. Data obtained at the first visit (baseline) and at 1 year were collected. In the KOCOSS, stable COPD patients are prospectively recruited from the outpatient clinics of 47 referral hospitals in Korea; enrollment commenced in December 2011 and is still ongoing. The inclusion criteria are as follows: diagnosis of COPD by a pulmonologist; age ≥40 years; cough, sputum production, and dyspnea; and a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio ≤70% of the normal predicted value. Medical history-taking at baseline includes the frequency and severity of exacerbations in the previous 12 months, the body mass index (BMI), smoking status, patient-reported education level, medications taken (including those already prescribed for COPD), and comorbidities. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score is also recorded, as are the results of the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the COPD-specific version of St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). The 6-MWD is also performed. All data are recorded on electronic case report forms that are completed by physicians or trained nurses, and all patients are evaluated at 6-month intervals after initial examination. Blood tests are used to measure the levels of inflammatory markers and various chemicals and blood cell counts. The major exclusion criteria are as follows: asthma; other obstructive lung diseases, including bronchiectasis or tuberculous lung destruction; an inability to complete the pulmonary function test; myocardial infarction (MI) or a cerebrovascular event within the previous 3 months; pregnancy; rheumatoid disease; a malignancy; irritable bowel disease; and prescription of steroids for conditions other than COPD exacerbation within 8 weeks of enrollment. Exacerbations are defined as the worsening of any respiratory symptoms, including increased sputum volume, purulence, or advancing dyspnea, which require treatment with systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or both.5

Pulmonary functions and severity of airflow limitation

Spirometry was performed using standard techniques6 at baseline and repeated every year during follow-up. The severity of airflow limitation was classified using post-bronchodilator FEV1 data alone, in accordance with both the 20114 and 2017 GOLD guidelines1; stage 1: FEV1 ≥80% predicted; stage 2 ≤50% to 80% predicted; stage 3 ≤30% to 50% predicted; and stage 4 <30% predicted. The 6-MWD assessed functional capacity in accordance with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.7 A rapid decliner was defined as a patient with an FEV1 decline >60 mL/year.8

Quality of life and dyspnea scores

The SGRQ was administered to assess patient-perceived health status. The SGRQ is a 14-item questionnaire with symptom (SGRQ-S), activity (SGRQ-A), and impact (SGRQ-I) subscales. The total and three subscale scores were calculated as described in the SGRQ instruction manual.9

Dyspnea was evaluated using the mMRC dyspnea scale (a five-point scale on which higher scores indicate more severe dyspnea) and the CAT score. The CAT consists of eight items, each scored from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.1

COPD assessment

All patients were categorized into four groups (GOLD A, B, C, or D) according to the 2011 GOLD criteria by assessing the FEV1, dyspnea scores, and exacerbation frequency.4

The patients were also categorized into four groups (GOLD A, B, C, or D) according to the 2017 GOLD recommendations by assessing symptoms and exacerbation frequency.1

Patients who were in the 2017 GOLD B at baseline and remained in that category for 1 year were defined as BB patients (stable), and those who deteriorated to GOLD D at 1 year were defined as BD patients (unstable).

Non-specific inflammatory markers

We recorded the white blood cell (WBC) count, the proportion of neutrophils, the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), the C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to analyze differences in inflammatory marker levels between GOLD B and GOLD D patients and to explore the natural course of GOLD B patients.

Statistical analyses

We compared the characteristics of GOLD B and GOLD D patients with 2017 GOLD classification. Differences between groups were analyzed using the two-sample t-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. We analyzed natural course of the 2017 GOLD B patients at 1 year later from baseline. We explored the redistribution of 2011 GOLD patients to the 2017 GOLD categories. After univariate analyses of the differences between groups BB and BD, multiple logistic regressions were used to adjust for potential confounding factors of GOLD B patients who progressed to GOLD D at 1 year. All tests were two-sided, and a P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics according to the 2017 GOLD classification

We recruited 2,010 patients and their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of them, 1,261 (62.7%) were in the 2017 GOLD B group and 277 (13.8%) were in the 2017 GOLD D group. The GOLD B group contained more current smokers than did the GOLD D group (28.6% vs 19.9%, respectively, P=0.031). However, the smoking level did not differ between the groups. The historical rates of MI, chronic bronchitis, gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), and pneumonia were significantly lower in the GOLD B group than in the GOLD D group. Both FEV1 values and the 6-MWD were higher in the GOLD B group than in the GOLD D group. The mMRC, CAT, and SGRQ scores were lower in the GOLD B group than in the GOLD D group. The levels of inflammatory markers and mean WBC count, neutrophil level, NLR, CRP level, and ESR were lower in the GOLD B group than in the GOLD D group. The frequency of exacerbations during the previous 1 year was lower in the GOLD B group than in the GOLD D group.

The natural course of GOLD B patients according to the 2017 classifications

The GOLD A group contained 21.5% (n=433) of all patients and the GOLD C group contained 1.9% (n=39) (Figure 1A). A total of 625 of the 1,261 GOLD B patients attended their 1-year follow-ups. Most GOLD B patients remained in group B at 1 year (n=432, 69.1%). Eighty-six patients (13.8%) progressed to GOLD D (Figure 1B).

Patient distribution by GOLD classification

Using the 2011 GOLD classification, 16.8% of the patients were in group A, 37.7% were in group B, 5.2% were in group C, and 34.4% were in group D (Figure 2A). Figure 2B shows the cumulative distribution of each 2011 GOLD group within each 2017 GOLD group. The 2017 GOLD A group included 2011 GOLD A (83.1%) and 2011 GOLD C (16.9%) patients. The 2017 GOLD B group was composed of 2011 GOLD B (63.7%) and 2011 GOLD D (36.3%) patients. The 2017 GOLD C and D groups were composed of 2011 GOLD C (100%) and D (100%) patients, respectively. Patients of 2011 GOLD C group were redistributed to the 2017 GOLD A (64.54%) and C (35.45%) groups. Patients in the 2011 GOLD D were redistributed to the 2017 GOLD B (61.63%) and D (38.36%) groups (Figure 2C).

Progression of GOLD B patients to GOLD D using the 2017 classification

The baseline characteristics of the BB and BD patients are shown in Table 2. The baseline FEV1 was significantly lower in BD patients compared to BB patients. Baseline age and the mMRC, SGRQ-S, SGRQ-A, SGRQ-I, and SGRQ total scores were significantly higher in BD patients than in BB patients. The percentage of patients with chronic bronchitis was higher in the BD patients (P=0.003). Inflammatory marker levels did not differ significantly between the BB and BD patients, with the exception of the WBC count (Table 2).

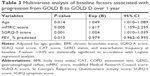

In multivariate analysis, age, the mMRC and SGRQ-S scores, and the % predicted FEV1 were significantly associated with progression from GOLD B to GOLD D at 1 year after adjusting for sex, BMI, the presence of chronic bronchitis, the SGRQ-A, SGRQ total and CAT scores, a history of GERD, and exacerbation frequency at baseline (Table 3).

Changes in FEV1

The mean change in FEV1 from baseline over 1 year was an increase of 39 mL in the BB patients and a reduction of 62 mL in the BD patients (P=0.005) (Figure 3A). Thirty-one patients (45.6%) exhibited declines >60 mL over 1 year in the BD group, as did 112 BB patients (33%) (P=0.045) (Figure 3B).

Discussion

We found that older age, a higher level of respiratory symptoms, poorer health status, and a lower % predicted FEV1 at baseline were associated with progression from GOLD B to GOLD D over 1 year with the 2017 GOLD classification, similar to the results when the 2011 GOLD classification was employed.3 This is the first report to identify GOLD B patients who progressed to GOLD D and the factors associated with such progression, using the 2017 GOLD guidelines. Most GOLD B patients retained GOLD B at 1 year, but 13.8% progressed to GOLD D. Although homogenous terms of the mMRC scale, CAT scores, and the exacerbation frequency were used to assess the GOLD B group, the natural courses of GOLD B patients were heterogeneous.

We found that older GOLD B patients progressed to GOLD D more readily. The exacerbation rates increase with age;10 lung function declines with aging in never smokers,11 and this decline is accelerated in smokers.12 The decline in FEV1 accelerates nonlinearly after the age of 70 years.13 In our cohort, the mean age of all patients was 70 years. GOLD D patients were 1 year older than GOLD B patients, and BD patients were 2 years older than BB patients. Older COPD patients may be at an increased risk of exacerbation, as are patients with greater airflow limitations. Aging accelerates the decline in lung function and contributes to COPD deterioration.

In our study, the mMRC, SGRQ symptom, activity, and total scores were higher in GOLD B patients who deteriorated than in those who did not. In the COPDMAP cohort, the CAT, SGRQ activity, and total scores were higher in GOLD B patients who deteriorated.3 In the 2017 GOLD assessment, the only difference between GOLD B and D patients is the exacerbation frequency;1 deterioration from GOLD B to GOLD D implies an increased exacerbation frequency. In the Hokkaido COPD cohort, patients who experienced exacerbations exhibited reduced lung function, more dyspnea, and a higher SGRQ total score compared to patients who did not experience exacerbations.14 Impaired health-related quality of life induced exacerbations, but the influential SGRQ domain in exacerbations differed between cohorts. In multivariate analysis, the symptom domain score was significantly associated with exacerbations in the KOCOSS cohort, while the activity domain score was significantly associated with exacerbations in the Hokkaido COPD cohort.14 Dyspnea is one of the major forms of exacerbation, reducing physical activity and health status. It is possible that more severe symptoms or symptom-related health issues increase exacerbations.

Patients with fewer symptoms, a lower risk of exacerbations, and FEV1 values <50% were categorized as GOLD C in the 2011 classification. However, using the 2017 classification, those with fewer symptoms and a lower risk of exacerbations are categorized as GOLD A regardless of FEV1 status. The omission of FEV1 in terms of COPD assessment redistributes some GOLD C patients to the GOLD A group and some GOLD D patients to the GOLD B group. Although the 2017 GOLD classification does not use the FEV1, the FEV1 significantly influenced the progression of GOLD B patients to GOLD D in our study, similar to what is found when FEV1 is used to assess COPD.3 A lower FEV1 was significantly related to increased exacerbations that redistributed GOLD B patients to GOLD D after 1 year. An FEV1 decline increased the risk of exacerbation. In the ECLIPSE cohort, the rate of exacerbations requiring hospitalization increased as the airflow limitation rose.10 Recent study found that the 2017 GOLD classification did not predict mortality more accurately than the 2011 classification.15 Although, the current GOLD criteria do not use the FEV1 to assess COPD, we intend to retain our focus on the FEV1 to assess, treat, and predict outcomes of COPD.

The annual lung function declines were 44, 48, 38, and 39 mL in groups A–D of the UPLIFT trial, respectively.16 The FEV1 declines did not differ among the groups (33.4, 38.0, 30.2, and 31.9, respectively);17 these data were derived using the 2011 GOLD classification. In our cohort, rapid decliners were significantly more common in the deteriorating BD patients than in the stable BB patients. The frequency of rapid decliners in GOLD B patients was lower (34%, data not shown) in our cohort than in the COPDMAP cohort (58.7%).3 Uniquely, we found a prominent difference in lung function decline between deteriorating BD and stable BB patients at 1 year. In the COPDMAP cohort, the changes in FEV1 from baseline were −80 mL in a stable group and −120 mL in an unstable group. In our cohort, BB patients (defined as “stable” in the COPDMAP cohort) exhibited an increase in FEV1 of 39 mL at 1 year, and BD patients (defined as “unstable” in the COPDMAP cohort) showed a decrease of 62 mL. Lung function decline in our cohort differed from that of the COPDMAP cohort.

The limitations of our study include the low percentage of females and high percentage of dropouts during longitudinal follow-up. Nonetheless, the KOCOSS cohort is representative of real-world study and reflects real-world practice. We examined the characteristics of GOLD B patients and the natural course of the GOLD B patients in a large patient sample.

Conclusion

Most COPD patients are GOLD B, and most GOLD B patients remained in group B after 1-year follow-up on application of the 2017 criteria. GOLD B patients who progressed to GOLD D had higher mMRC and SGRQ symptom scores and lower FEV1 values than did those who remained GOLD B. This means that GOLD B patients who are highly symptomatic and have more severe airflow limitations are at high risk of exacerbations. We suggest that such patients require early treatment and close monitoring.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of all participating centers. The study was also approved by the IRBs of all hospitals (Seoul National University Hospital IRB, Catholic Medical Center Central IRB, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine IRB, Severance Hospital IRB, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital IRB, Ajou University Hospital IRB, Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Pyeongchon Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hanyang University Guri Hospital IRB, Konkuk University Hospital IRB, Konkuk University Chungju Hospital IRB, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital IRB, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center IRB, Korea University Guro Hospital IRB, Korea University Anam Hospital IRB, Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital IRB, Dong-A University Hospital IRB, Gachon University Gil Medical Center IRB, Gangnam Severance Hospital IRB, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong IRB, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital IRB, Kangwon National University Hospital IRB, Kyungpook National University Hospital IRB, Gyeongsang National University Hospital IRB, Pusan National University Hospital IRB, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital IRB, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital IRB, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University IRB, Asan Medical Center IRB, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital IRB, Eulji General Hospital IRB, Samsung Medical Center IRB, Ulsan University Hospital IRB, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital IRB, Yeungnam University Hospital IRB, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital IRB, Inha University Hospital IRB, Chonbuk National University Hospital IRB, and Jeju National University Hospital IRB). All patients provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study.

Acknowledgment

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/Ke27oO.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [homepage on the Internet]. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; 2017. Available from: www.goldcopd.org. Accessed September 17, 2018. | ||

Agusti A, Edwards LD, Celli B, et al; ECLIPSE Investigators. Characteristics, stability and outcomes of the 2011 GOLD COPD groups in the ECLIPSE cohort. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(3):636–646. | ||

Lawrence PJ, Kolsum U, Gupta V, et al. Characteristics and longitudinal progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in GOLD B patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):42. | ||

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–365. | ||

Lee JY, Chon GR, Rhee CK, et al. Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease at the First Visit to a Pulmonary Medical Center in Korea: The KOrea COpd Subgroup Study Team Cohort. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(4):553–560. | ||

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. | ||

ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):111–117. | ||

Ramírez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, Quintana-Carrillo RH, et al. FEV1 decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with biomass exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(9):996–1002. | ||

Meguro M, Barley EA, Spencer S, Jones PW. Development and Validation of an Improved, COPD-Specific Version of the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire. Chest. 2007;132(2):456–463. | ||

Müllerova H, Maselli DJ, Locantore N, et al. Hospitalized exacerbations of COPD: risk factors and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Chest. 2015;147(4):999–1007. | ||

Ware JH, Dockery DW, Louis TA, Xu XP, Ferris BG, Speizer FE. Longitudinal and cross-sectional estimates of pulmonary function decline in never-smoking adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(4):685–700. | ||

Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977;1(6077):1645–1648. | ||

Sharma G, Goodwin J. Effect of aging on respiratory system physiology and immunology. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(3):253–260. | ||

Suzuki M, Makita H, Ito YM, Nagai K, Konno S, Nishimura M; Hokkaido COPD Cohort Study Investigators. Clinical features and determinants of COPD exacerbation in the Hokkaido COPD cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1289–1297. | ||

Gedebjerg A, Szépligeti SK, Wackerhausen LH, et al. Prediction of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with the new Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 classification: a cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(3):204–212. | ||

Goossens LM, Leimer I, Metzdorf N, Becker K, Rutten-van Mölken MP. Does the 2013 GOLD classification improve the ability to predict lung function decline, exacerbations and mortality: a post-hoc analysis of the 4-year UPLIFT trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14(14):163. | ||

Kim J, Yoon HI, Oh YM, et al. Lung function decline rates according to GOLD group in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1819–1827. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.