Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Voice Contributes to Creativity via Leaders’ Endorsement Especially When Proposed by Extraverted High Performance Employees

Authors Shu M , Zhong Z, Ren H

Received 1 November 2021

Accepted for publication 21 January 2022

Published 1 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 213—226

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S347148

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Mian Shu, Zhengqiang Zhong, Han Ren

Business School, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Han Ren

Business School, Sichuan University, No. 24 South Section 1, Yihuan Road, Chengdu, Sichuan, 610064, People’s Republic of China

, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Drawing on social judgement theory and the self-determination theory, this study aims to test the moderating roles of employees’ extraversion and task performance in the effects of employees’ voice on leaders’ endorsement, as well as the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity, and more importantly, the moderated mediation model.

Methods: A total of 250 employees and their direct leaders participated in the two-wave multi-source survey. To examine the hypotheses, we conducted the hierarchical regression and bootstrapping analyses on the basis of Hayes PROCESS Model.

Results: Findings revealed that both extraversion and task performance serve as moderators in the effects of employees’ voice on leaders’ voice endorsement. Leaders’ voice endorsement significantly mediates the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity. More importantly, the results indicated that the indirect effect of leaders’ voice endorsement on the association of employees’ voice and creativity is significantly positive only when the employees are extraverted high performers, that is, there is a significant moderated mediation.

Conclusion: The present study extends the current literature by exploring the moderated mediation mechanism between employees’ voice, extraversion, task performance, leaders’ voice endorsement, and employees’ creativity. Our findings recommend leaders to be aware of the mediating role of their endorsement of employees’ voice and the moderating roles of employees’ extraversion and performance in linking employees’ voice to their creativity.

Keywords: voice endorsement, extraversion, task performance, creativity, moderated mediation

Introduction

Voice refers to the behavior of expressing ideas, opinions, suggestions, or alternative approaches that aims at organizational change and improvement.1 It has long been considered a critical behavior that benefits employees, work units, and organizations. Prior work has highlighted that organizations and work units thrive on the ideas and suggestions of their employees.2,3 Meanwhile, employees who speak up to share their opinions in this way tend to be seen as active contributors and more effective in their jobs, which in turn advances their careers.4,5 Given the apparent importance of voice, numerous studies have been conducted on its antecedents and consequences.6–9

Studies examining the outcomes of voice for individuals are exceptionally rich, but their findings are rather mixed.1 Although several meta-analysis studies10–12 have confirmed the positive effect of voice on individual performance (leader-, peer-, and self-rated overall or in-role performance), the challenging nature of voice (ie, change-oriented in its motive) may actually harm the voicer and bring forth the risk of being misunderstood and other undesirable social consequences.13 For example, Seibert et al14 found a negative effect of voice on career progression and no effect on career satisfaction. Aside from the potential risk of voice itself, leaders’ response to/feedback on employees’ voice (eg, leader voice endorsement) is a key factor that alters the impact of voice for individuals. Hunton et al15 revealed that when voice is ignored, it would result in a 41% reduction in output in comparison to when it was endorsed.

Considering the critical role of voice endorsement, scholars have spared no effort to shed light on the mechanism whereby leaders choose to endorse and act upon employees’ voice. Several factors, such as leader’s status (eg, ego depletion),16 leader-voicer relationship (eg, leader-member exchange quality),17 voicer’s political skill,18 voicer’s proactive personality,1 voicer’s politeness,20 and the type of voice (whether employees speak up in challenging or supportive ways),21 have been identified as critical moderators or predictors of voice endorsement. Although the current literature of voice endorsement helps to outline an initial framework of the relationship between employees’ voice and leaders’ endorsement, what is lacking is an integrated model whereby the influencing mechanism linking employees’ voice to leaders’ endorsement and to individual positive outcomes (eg, creativity) could be clarified.

In this study, we drew on social judgement theory22,23 and self-determination theory24,25 to propose an integrated theoretical framework of the impact of employees’ voice on creativity via leaders’ endorsement. Social judgement theory posits that people’s behavior toward a target is governed by their judgments of the target’s warmth (eg, friendliness, kindness, politeness) and competence (eg, ability, intelligence, skills).20,22 Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that employees’ extraversion (a personality trait related to warmth) and task performance (an indicator of competence) moderate the association of voice with leaders’ endorsement. In addition, according to self-determination theory,24,25 people have three basic and universal motivations—autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and the satisfaction of these needs has a significant impact on individual attitudes and behaviors. Leaders’ endorsement of employees’ voice contributes to the satisfaction of employees’ need for competence and relatedness, which in turn leads to increased creativity.

Taken together, the purposes of this study are to test the moderating roles of both extraversion and task performance in the effects of employees’ voice on leaders’ voice endorsement, as well as the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity; and more importantly, to test the moderated mediation model. In so doing, we start with a review of employees’ voice, extraversion, task performance, leaders’ voice endorsement, and employees’ creativity, in order to propose the moderated mediation model (shown in Figure 1) and hypotheses. Then, we examine our hypotheses using two-wave multi-source surveys of Chinese employees and their leaders. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications as well as the limitations and future directions of this paper.

|

Figure 1 The moderated mediation model in this study. |

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Employees’ Voice and Leaders’ Voice Endorsement

The original conceptualization of voice is derived from Hirschman,26 who defines voice as “directed to a higher authority and intended to bring change or improvement to an existing, objectionable state” (p. 16). Although this concept has been regarded as “messy”, it foreshadows the breadth of conceptual frameworks in voice studies.27–29 One of the popular conceptual frameworks of voice is given by Liang et al.29 Based on the work of Van Dyne and Lepine,28–30 Liang et al distinguished two major types of voice: promotive voice and prohibitive voice. Promotive voice refers to “employees’ expression of new ideas or suggestions for improving the overall functioning of the work unit or organization” (p. 74). Prohibitive voice refers to “employees’ expressions of concern about work practices, incidents, or employee behavior that is harmful to the organization” (p. 75). In this study, we focus on both types of voice and combine their ratings as a whole.

Numerous studies have focused on the aspects of voice including the antecedents and outcomes of its expression and associated factors. Morrison31 offered a general theoretical framework in which the antecedents of voice were placed into five categories: (a) individual dispositions; (b) schemas, beliefs, and emotions; (c) organizational and job perceptions and attitudes; (d) supervisor and leader behavior; and (e) other contextual factors. Bashshur & OC,1 in contrast, focused on the individual outcomes of voice, with five primary categories: job performance, justice perceptions, job attitudes (eg, job satisfaction, organizational commitment), relational outcomes (eg, trust, loyalty, liking, leader support, leader–employee relationships), and withdrawal/exit. More interestingly, scholars shed light on the moderating roles of some factors in the impact of voice. For example, Whiting et al32 found that the link of voice with performance is further strengthened when there is a norm for speaking up in the organization, when the voicer is an expert in the focal area and trustworthy, and when voice provides a solution.

Indeed, scholars have made remarkable progress in understanding employees’ voice and its outcomes; however, what remains less clear is why and why not leaders choose to endorse these voices. It is clear that leaders’ endorsement of voice matters a lot; by Hunton et al15 found that when voice was ignored, there was a 41% reduction in output compared to when it was endorsed. Some pioneering studies have focused on the factors that predict or moderate the link between employees’ voice and leaders’ endorsement. An early work of Burris21 suggested that leaders tend to view employees who speak up in more challenging ways as worse performers and endorse their suggestions and ideas less than those who voice in supportive forms. In particular, employees who intended to alter, modify, or destabilize generally accepted sets of practices, policies, or strategic directions were considered as “speaking up in more challenging ways” (p. 852), while those who intended to stabilize or preserve existing organizational policies or practices were seen as “voicing in supportive forms” (p. 853).

Despite the challenging or supportive ways in which the voicer expresses his or her opinions, leader’s ego depletion16 and leader-employee exchange quality17 significantly impact leaders’ voice endorsement as well. Additionally, some individual characteristics of the voicer play critical roles in the mechanism of leaders’ voice endorsement. These individual characteristics include proactive personality and task performance,19 political skill,18 and voicer politeness and credibility.20 In a word, the voice expressed by those employees who are viewed as proactive, polite, and trustworthy, and with high levels of political skills and better task performance, is more likely to be endorsed by the leaders.

The Moderating Roles of Employees’ Extraversion and Task Performance

Drawing on social judgement theory, we expect that employees’ extraversion and task performance moderate the relationship between voice and leaders’ voice endorsement. As noted previously, the social judgment theory emphasizes that people tend to judge a target’s warmth and competence first, and then to use those judgments to decide how to behave toward the target.22,23,33 We use employees’ extraversion and task performance as indicators for warmth and competence, respectively.

Extraversion, as one factor in the Big Five model of personality traits, reflects individual’s sociability.34 Extraverted individuals are regarded as more sociable and active, but less dysphoric and self-preoccupied than introverts (p. 769).35 Moreover, extraversion is also closely related to positive emotionality/affectivity, which in turn expresses itself in positive moods, greater social activity, and more rewarding interpersonal experiences.34,35 Numerous meta-analysis studies have focused on the relationship between the Big Five factors and individual outcomes such as performance,36 work values,37 career success,34 and organizational citizenship behaviors;38 overall, extraversion has positive impacts. In the context of voice, we believe that extraverted employees are more likely to be viewed as having higher levels of friendliness and kindness, which contributes to making a stronger impression of warmth on the leader. Accordingly, the voice expressed by extraverted employees is more likely to be endorsed by leaders than those proposed by introverts. Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ extraversion moderates the association between employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement, such that the association is more positive when the employees are more extravert.

There are many indicators of competence; in this study, we use task performance because it is one of the most important individual outcomes in organizational settings and can be easily rated by the leader. Employees with better task performance and reputations are viewed as more trustworthy39,40 and their ideas and suggestions are more likely to be viewed as constructive and useful. Prior research found that an audience (a receiver) is more likely to be persuaded by a trustworthy speaker (voicer), even when there is no difference in the content.41 In terms of voice endorsement, Whiting et al32 and Lam et al20 showed that voice proposed by a more credible source or voicer tends to be viewed as more constructive, resulting in better performance evaluations of that voicer and greater likelihood to be endorsed by the leader. Accordingly, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ task performance moderates the association between employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement, such that the association is more positive when the employees’ task performance is higher.

As noted above, social judgement theory highlights two critical factors of the target: warmth, and the competence that people need to form a judgement to further guide the following behaviors toward the target.22,23,33 It is reasonable to argue that employees’ extraversion and task performance tend to simultaneously moderate the link of voice with leaders’ voice endorsement. Specifically, when the voicer is an extraverted high performer, the leader tends to judge the target in terms of warmth and competence, and accordingly chooses to endorse his/her voice. But for other voicers such as extraverted poor performer, introverted high performer, and introverted poor performer, the leader cannot view them in terms of warmth and competence simultaneously, which in turn results in a denial or negative feedback on their voice. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ extraversion and task performance simultaneously moderate the association between employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement such that the association is the most positive when the employees are more extraverted and their task performance is higher.

The Mediating Role of Leaders’ Voice Endorsement

As introduced above, the self-determination theory24,25 posits that there are three universal and basic motivations—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—for human beings, and whether these needs are satisfied or not has paramount influence on people’s behaviors. It is a common notion that when employees’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied, they are more likely to engage in positive behaviors such as organizational citizenship behaviors42 and creativity.43,44 A leader’s endorsement of an employee’s voice signals recognition and appreciation of this employee and his/her ideas and suggestions, which in turn contribute to the satisfaction of the employee’s need for competence and relatedness and to more creativity. Hence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 4: Leaders’ voice endorsement mediates the link between employees’ voice and creativity.

The Moderated Mediation Model

Integrating the insights of the social judgement theory22,23 and the self-determination theory,24,25 we argue that there should be a moderated mediation model in which employees’ extraversion and task performance moderate the mediating effect of leaders’ voice endorsement on the impact of employees’ voice on creativity. In particular, for extraverted high performers, the positive effect of employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement is augmented, which strengthens the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity. Meanwhile, for other voicers (including extraverted poor performer, introverted high or poor performer), the impact of employees’ voice on leaders’ voice endorsement is weakened, which neutralizes the role of leaders’ voice endorsement in mediating the effects of employees’ voice on creativity. Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 5: Employees’ extraversion and task performance simultaneously moderate the mediating effect of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity such that the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement is the most positive when the employees are more extraverted and their task performance is higher.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A total of 250 employees and their direct leaders from one large-scale state-owned enterprise located in North China participated in the study. To reduce the potential risk of common method bias,45 we employed a two-wave multi-source design. The questionnaires were distributed to the employees and their direct leaders with the assistance of the human resources manager. To reduce participants’ potential concerns about being evaluated, and to assure confidentiality, each questionnaire was enclosed within an envelope. To ensure the two-wave multi-source surveys could be matched, we asked the participants to write down an identity verification code. Employees rated their own extraversion and demographics (Time 1) as well as their direct leader’s voice endorsement (Time 2, one month later). Leaders evaluated their employees’ voice (Time 1) and their task performance and creativity (Time 2). All participants reported their sex, age, tenure, and education level. Of the 250 employees, 95.1% were male and 48% had a high school diploma or above. Their average age was 39.7, and they had an average of 13.9 years of organizational tenure.

Measures

All substantive variables were rated on 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). We followed the guidance of Brislin (1986)46 to translate all English items into Chinese.

Employees’ Voice

We used two items from the measure of promotive voice and prohibitive voice of Liang et al29 and asked leaders to provide ratings of employees’ voice. The two items are “This employee proactively develops and makes suggestions for issues that may influence the unit” and “This employee advises other colleagues against undesirable behaviors that would hamper job performance.” The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.907.

Leaders’ Voice Endorsement

We adopted three items from the measure of voice endorsement developed by Burris21 and invited employees to evaluate their direct leader’s voice endorsement. One sample item is “My leader thinks the employees’ comments are valuable”. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.904.

Employees’ Extraversion

We used the four-item scale of extraversion from the 20-item Mini International Personality Item Pool developed by Donnellan et al.47 The Mini-IPIP is derived from the 50-item IPIP-Five Factor Model developed by Goldberg.48 One sample item is “I usually talk to a lot of different people at parties”. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for these four items was 0.674, meeting the minimum level of 0.60 for acceptable reliability, according to Nunnally.49

Employees’ Task Performance

We used one item and asked leaders to provide overall ratings of their employees’ task performance. This item is “How would you evaluate this employee’s task performance?”.

Employees’ Creativity

Employees’ creativity was evaluated by their leaders using a four-item scale developed by Farmer et al.50 Sample items are “This employee tries new ideas or methods first” and “This employee seeks new ideas and ways to solve problems”. The Cronbach’s alpha for these four items was 0.936.

Control Variables

We included individuals’ demographic information such as sex, age, tenure, and education level as control variables. The education level was measured by five categories (1 = middle school diploma or below, 2 = high school diploma, 3 = associate diploma, 4 = bachelor degree, and 5 = graduate degree).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

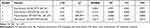

We conducted a series of CFA to examine the discriminant validity among the variables. Five factors were included: employees’ voice, extraversion, task performance, creativity, and leaders’ voice endorsement. The goodness of baseline five-factor model fit was compared to three alternative models using the data collected from leader-employee matched surveys. Results in Table 1 indicate that model 1 fit the data well (χ2/df = 1.97, RMSEA = 0.062, IFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.961, CFI = 0.971) and provided substantial improvement in fit indices over models 2–4.

|

Table 1 Comparison of Alternative Measurement Models |

Hypotheses Testing

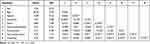

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. As shown in Table 2, employees’ voice was positively related to leaders’ voice endorsement (r = 0.193, p < 0.01) and creativity (r = 0.461, p < 0.01). Moreover, leaders’ voice endorsement was positively associated with employees’ creativity (r = 0.427, p < 0.01). We then conducted hierarchical regression to test Hypotheses 1 to 4, as shown in Table 3. Furthermore, we employed bootstrapping analyses on the basis of Hayes PROCESS Model 4 and Model 9 to examine Hypotheses 4 and 5, respectively.

|

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations of All Variables |

|

Table 3 Results of Hierarchical Regressions |

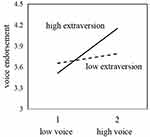

Hypothesis 1 predicted the moderating role of extraversion in the association of employees’ voice with leaders’ voice endorsement. Table 3 shows that the interaction of employees’ voice and extraversion had a significantly positive effect on leaders’ voice endorsement (β = 0.142, p < 0.05). We followed Aiken et al51 to explicate the interaction, as shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that for participants with high extraversion, employees’ voice was positively related to leaders’ voice endorsement (effect = 0.289, 95% CI = [0.138, 0.440], excluding zero); but for participants with low extraversion, it was not (effect = 0.062, 95% CI = [−0.081, 0.204], including zero). These results provide considerable support for Hypothesis 1.

|

Figure 2 The interactive effect of employees’ voice and extraversion on leaders’ voice endorsement. |

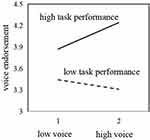

Similarly, Hypothesis 2 proposed the moderating role of task performance in the relationship between employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement. As shown in Table 3, the interaction of employees’ voice and task performance was positively related to leaders’ voice endorsement (β = 0.152, p < 0.05). We followed Aiken et al51 to explicate the interaction, as shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that for high performers, their voice was positively related to leaders’ voice endorsement (effect = 0.167, 95% CI = [−0.025, 0.358], including zero); but for low performers, their voice had a negative effect on leaders’ voice endorsement (effect = −0.059, 95% CI = [−0.194, 0.076], including zero). Hence, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

|

Figure 3 The interactive effect of employees’ voice and task performance on leaders’ voice endorsement. |

Hypothesis 3 predicted the simultaneously moderating roles of employees’ extraversion and task performance in the association between voice and leaders’ voice endorsement. Table 3 demonstrates that both the interaction of employees’ voice with extraversion (β = 0.136, p < 0.05) and the interaction of employees’ voice with task performance (β = 0.152, p < 0.05) had positive effects on leaders’ voice endorsement. We followed Aiken et al51 to explicate the interaction, as shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that for extraverted high performers, their voice was positively related to leaders’ voice endorsement (effect h-h = 0.282, 95% CI = [0.066, 0.499], excluding zero). But for others, their voice did not exert significant effects on leaders’ voice endorsement (effect l-l = −0.160, 95% CI = [−0.320, 0.000]; effect l-h = 0.066, 95% CI = [−0.144, 0.275]; effect h-l = 0.057, 95% CI = [−0.112, 0.225]; all including zero). These findings provide support for Hypothesis 3.

|

Figure 4 The simultaneous moderating effect of employees’ extraversion and task performance. |

Hypothesis 4 proposed that leaders’ voice endorsement mediates the association of employees’ voice and creativity. Based on Baron and Kenny’s procedure,52 we conducted a series of regressions. The results in Table 3 reveal a positive effect of employees’ voice on leaders’ voice endorsement (β = 0.216, p < 0.01) and creativity (β = 0.457, p < 0.01). More importantly, the effect of employees’ voice on creativity became less (β = 0.381, p < 0.01) when leaders’ voice endorsement entered the model. We further confirmed the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement by using bootstrapping analyses using Hayes PROCESS Model 4. The results showed that the 95% CIs with 10000 bootstrapped samples of the indirect effect of leaders’ voice endorsement linking employees’ voice to creativity (indirect effect = 0.076, SE = 0.026, 95% CI = [0.027, 0.129]) did not include zero. Hence, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

To examine Hypothesis 5, which predicted employees’ extraversion and task performance simultaneously moderate the mediating effect of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity, we conducted bootstrapping analyses using Hayes PROCESS Model 9. The results in Table 4 reveal an overall significant moderated mediation effect (the differences of “Effect 4 - Effect 1” = 0.172, SE = 0.066, 95% CI = [0.039, 0.297], excluding zero; “Effect 4 - Effect 3” = 0.088, SE = 0.046, 95% CI = [0.003, 0.183], excluding zero; “Effect 4 - Effect 2” = 0.084, SE = 0.042, 95% CI = [−0.013, 0.158], including zero). In particular, only for extraverted high performers, the indirect effect of leaders’ voice endorsement linking employees’ voice to creativity was significant (indirect effect h-h = 0.110, SE = 0.045, 95% CI = [0.019, 0.196], did not include zero). But for others, the indirect effect was not significant (indirect effect l-l =−0.062, SE = 0.041, 95% CI = [−0.147, 0.012]; indirect effect l-h = 0.026, SE = 0.044, 95% CI = [−0.062, 0.114]; indirect effect h-l =0.022, SE = 0.037, 95% CI = [−0.067, 0.080]; all included zero).

|

Table 4 Results of Moderated Mediating Effect |

Discussion

This study proposed and tested a moderated mediation model whereby the relationships among employees’ voice, extraversion, task performance, creativity, and leaders’ voice endorsement were revealed. Particularly, we detected the moderating roles of employees’ extraversion and task performance in the association between voice and leaders’ voice endorsement. Meanwhile, we found a mediating effect of leaders’ voice endorsement on the link between employees’ voice and creativity. More importantly, the findings indicated a significant moderated mediation mechanism in which employees’ extraversion and task performance simultaneously moderate the mediating effect of leaders’ voice endorsement in the relationship between employees’ voice and creativity.

Our findings largely supported the usage of the social judgment theory22,23,33 in examining the moderating mechanism linking employees’ voice to their leaders’ voice endorsement.20 In particular, employees’ extraversion and task performance acted as indicators of their warmth and competence, respectively. A leader’s decision on whether to endorse the suggestions raised by one employee or not is more likely to be affected by their judgement of this voicer16,18–20 in terms of his/her extraversion and task performance. More importantly, drawing on self-determination theory,24,25 we extend the linking path of employees’ voice and leaders’ voice endorsement to one of the important positive employees’ outcomes, creativity. In so doing, our study advances the current understandings of the outcomes of leader voice endorsement.

Theoretical Contributions

The results of this study extend the current literature of employees’ voice and its impact. First, we found significant moderating roles of extraversion and task performance in the association of employees’ voice with leaders’ voice endorsement. This is consistent with the prior findings that drew on social judgement theory to detect the moderating effects of the target’s warmth (voice politeness) and competence (voice credibility) on the relationship between voice and managerial endorsement.20 In this study, we confirmed that it is only when the voice is raised by an extraverted high-performance employee that leaders tend to accept and endorse it.

Second, we detected considerable support for the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement in the link between employees’ voice and creativity. Drawing on self-determination theory, employees whose voice receives positive responses (ie, endorsement) from their leaders would have a sense of fulfillment for their competence and relatedness needs, which in turn contribute to higher creativity. This study verified the mediating mechanism of leaders’ voice endorsement linking employees’ voice to creativity, which therefore contributes to understanding of the impact of employees’ voice and the positive role of leaders’ endorsement.

Third and more importantly, we revealed a moderated mediation mechanism in which two moderators (extraversion and task performance) and one mediator (leaders’ voice endorsement) were identified in the impact of employees’ voice on creativity. In particular, the positive effect of employees’ voice on creativity via leaders’ voice endorsement was the strongest for extraverted high-performance employees. In other words, leaders tend to accept and endorse the voice proposed by those employees who are characterized with higher extraversion and whose task performance is better; and leaders’ endorsement in turn motivates employees’ creativity. The present study is among the first to integrate social judgement theory and self-determination theory and to spotlight the moderated mediation mechanism underlying the impact of employees’ voice on creativity. Our findings provide a novel insight into “when and how employee voice could lead to positive outcomes like creativity”. That is, it depends on who is the one to propose it and whether the leader endorses it or not.

Practical Implications

This study shows that employees’ voice would only be endorsed by their leader when the voicer is characterized by a personality trait of extraversion and good task performance. Given the potential risk of voice, especially of prohibitive voice (ie, communications addressing existing problems to prevent harmful outcomes),29 employees should be aware that high levels of extraversion and task performance contribute to the “success” of voice, that is, leaders’ acceptance and endorsement. Meanwhile, organizations and managers should pay more attention to the voice proposed by those employees who are less extraverted and average performers; although leaders may be less likely to endorse those employees’ voice, it does not mean that their voice is useless or worthless.

Moreover, the findings in this study indicate the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement in the impact of employees’ voice and creativity. Therefore, it is clear that managers’ endorsement is critical for voicers to improve their creativity. Considering the great importance of voice and creativity, organizations may provide some training programs for employees to improve their ability and skills to raise their voice and for managers to identify and endorse their employees’ voice.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study has some limitations that need to be highlighted. First, the small sample incorporated in our study may restrict the generalizability of our findings. We encourage future research to use larger samples to examine the underlying mechanism among employees’ voice, extraversion, task performance, creativity, and leaders’ voice endorsement.

Second, despite the use of two-wave multi-source design in collecting data from both employees and their leaders, common method variance may still be a limitation in this study. Fortunately, the results of CFA showed good discrimination validity among the variables, which helps to relieve this concern. We encourage future work to employ longitudinal or qualitative methods. Third, we only detected the moderating roles of extraversion and task performance and the mediating role of leaders’ voice endorsement examine other moderating and mediating factors in the impact of employees’ voice on other outcomes.

Conclusions

This study extends the current literature of employees’ voice by examining a moderated mediation model in which two moderators (extraversion and task performance) and one mediator (leaders’ voice endorsement) were identified in the influencing mechanism of employees’ voice on their creativity. Our study provides substantive support for the notion that social judgment theory22,23,33 could serve as a theoretical rationale in predicting leaders’ voice endorsement.20 More importantly, drawing on self-determination theory,24,25 our findings also advance the current understandings of the outcomes of leader voice endorsement by linking it to employees’ creativity. We recommend organizations and leaders to be aware of the importance of voice endorsement in improving employees’ creativity and to provide training programs to help employees better raise their voice.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee on Human Experimentation of Sichuan University and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. In the first-wave questionnaire, we introduced the study purposes and explained that this study welcomed voluntary participation and the data, complying with the principle of confidentiality, is only used for research purposes. Before responses to the questionnaire, all participants filled in a written informed consent form, claimed their understanding of the study purposes and that they would like to participate in the study voluntarily.

Funding

The work was supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project No.: 2018M643513).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bashshur MR, Oc B. When voice matters: a multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. J Manage. 2015;41(5):1530–1554. doi:10.1177/0149206314558302

2. Farh CIC, Chen Z, Kozlowski SWJ, Chen G. Beyond the individual victim: multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams. J Appl Psychol. 2014;99(6):1074–1095. doi:10.1037/a0037636

3. Mackenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP. Challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors and organizational effectiveness: do challenge-oriented behaviors really have an impact on the organization’s bottom line? Pers Psychol. 2011;64(3):559–592. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01219.x

4. Burris ER, Detert JR, Romney AC. Speaking up vs. being heard: the disagreement around and outcomes of employee voice. Organ Sci. 2013;24(1):22–38. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0732

5. Chamberlin M, Newton DW, Lepine JA. A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Pers Psychol. 2017;70(1):11–71. doi:10.1111/peps.12185

6. Barry M, Wilkinson A. Employee voice, psychologisation and human resource management (HRM). Hum Resour Manag J. 2021. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12415

7. Detert JR, Burris ER. Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manage J. 2007;50(4):869–884. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2007.26279183

8. Morrison EW. Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research. Acad Manag Ann. 2011;5(1):373–412. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.574506

9. Liu W, Song Z, Li X, Liao Z. Why and when leader’s affective states influence employee upward voice. Acad Manage J. 2017;60(1):238–263. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1082

10. Colquitt JA, Conlon DE, Wesson MJ, Porter COLH, Ng KY. Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:425–445. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.425

11. Thomas JP, Whitman DS, Viswesvaran C. Employee proactivity in organizations: a comparative meta-analysis of emergent proactive constructs. J Occup Organ Psych. 2010;83(2):275–300. doi:10.1348/096317910X502359

12. Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Employee voice behavior: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J Organ Behav. 2012;33:216–234. doi:10.1002/job.754

13. Morrison EW, Milliken FJ. Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25:706–725. doi:10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

14. Seibert SE, Kraimer ML, Crant JM. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Pers Psychol. 2001;54(4):845–874. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00234.x

15. Hunton JE, Price KH, Hall TW. A field experiment examining the effects of membership in voting majority and minority subgroups and the ameliorating effects of postdecisional voice. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:806–812. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.6.806

16. Li JJ, Barnes CM, Yam KC, Guarana CL, Wang L. Do not like it when you need it the most: examining the effect of manager ego depletion on managerial voice endorsement. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(8):869–882. doi:10.1002/job.2370

17. Isaakyan S, Sherf E, Tangirala S, Guenter H. Keeping it between us: managerial endorsement of public versus private voice. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(7):1049–1066. doi:10.1037/apl0000816

18. Liao C, Liden RC, Liu Y, Wu J. Blessing or curse: the moderating role of political skill in the relationship between servant leadership, voice, and voice endorsement. J Organ Behav. 2021;42(8):987–1004. doi:10.1002/job.2544

19. Duan J, Zhou AJ, Yu L. A dual-process model of voice endorsement. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2021;1–23. doi:10.1080/09585192.2021.1949624

20. Lam CF, Lee C, Sui Y. Say it as it is: consequences of voice directness, voice politeness, and voicer credibility on voice endorsement. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(5):642–658. doi:10.1037/apl0000358

21. Burris ER. The risks and rewards of speaking up: managerial responses to employee voice. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(4):851–875. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0562

22. Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Beninger A. The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Res Organ Behav. 2011;31:73–98. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004

23. Hovland CI, Janis IL, Kelley HH. Communication and Persuasion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1953.

24. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

25. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol. 2008;49(3):182–185. doi:10.1037/a0012801

26. Hirschman AO. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1970.

27. Maynes TD, Podsakoff PM. Speaking more broadly: an examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2014;99(1):87–112. doi:10.1037/a0034284

28. Van Dyne L, Lepine JA. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad Manage J. 1998;41:108–119. doi:10.2307/256902

29. Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh J. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(1):71–92. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0176

30. Van Dyne L, Ang S, Botero IC. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J Manage Stud. 2003;40(6):1359–1392. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00384

31. Morrison EW. Employee voice and silence. Annu Rev Organ Psych. 2014;1:173–197. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

32. Whiting SxW, Maynes TD, Podsakoff NP, Podsakoff PM. Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(1):159–182. doi:10.1037/a0024871

33. Wojciszke B. Multiple meanings of behavior: construing actions in terms of competence or morality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:222–232. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.222

34. Judge TA, Higgins CA, Thoresen CJ, Barrick MR. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers Psychol. 1999;52(3):621–652. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x

35. Watson D, Clark LA. Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In: Hogan R, Johnson J, Briggs S, editors. Handbook of Personality Psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997:767–793.

36. Brown TJ, Mowen JC, Donavan DT, Licata JW. The customer orientation of service workers: personality trait effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings. J Marketing Res. 2002;39(1):110–119. doi:10.1509/jmkr.39.1.110.18928

37. Furnham A, Petrides KV, Tsaousis I, Pappas K, Garrod D. A cross-cultural investigation into the relationships between personality traits and work values. J Psychol. 2005;139(1):5–32. doi:10.3200/JRLP.139.1.5-32

38. Chiaburu DS, Oh I, Berry CM, Li N, Gardner RG, Kozlowski SWJ. The five-factor model of personality traits and organizational citizenship behaviors: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(6):1140–1166. doi:10.1037/a0024004

39. Hochwarter WA, Ferris GR, Zinko R, Arnell B, James M. Reputation as a moderator of political behavior-work outcomes relationships: a two-study investigation with convergent results. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):567–576. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.567

40. Ostrom E. Toward a behavioral theory linking trust, reciprocity, and reputation. In: Ostrom E, Walker J, editors. Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003:19–79.

41. Hovland CI, Weiss W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin Quart. 1951;15(4):635–650. doi:10.1086/266350

42. Kanat-Maymon Y, Yaakobi E, Roth G. Motivating deference: employees’ perception of authority legitimacy as a mediator of supervisor motivating styles and employee work-related outcomes. Eur Manag J. 2018;36(6):769–783. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2018.02.004

43. Zhou H, He H. Exploring role of personal sense of power in facilitation of employee creativity: a dual mediation model based on the derivative view of self-determination theory. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2020;13:517–527. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S257201

44. Pan W, Sun L, Lam LW. Employee-organization exchange and employee creativity: a motivational perspective. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2020;31(3):385–407. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1331368

45. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee J, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

46. Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instrument. In: Lonner W, Berry J, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage; 1986:137–164.

47. Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE, Strauss ME. The mini-ipip scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(2):192–203. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

48. Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary IJ, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999:7–28.

49. Nunnally J. Psychometric Methods. New York: McGraw Hill; 1967.

50. Farmer SM, Tierney P, Kung-Mcintyre K. Employee creativity in Taiwan: an application of role identity theory. Acad Manage J. 2003;46(5):618–630.

51. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications Inc; 1991.

52. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.