Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Relationship Between Teacher–Student Relationship and Adolescent Emotional Intelligence: A Chain-Mediated Mediation Model of Openness and Empathy

Authors Wan S , Lin S, Yirimuwen, Li S, Qin G

Received 1 December 2022

Accepted for publication 5 April 2023

Published 20 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1343—1354

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S399824

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Simin Wan,1,* Shuwei Lin,1,* Yirimuwen,2 Sijie Li,3 Guihua Qin1

1School of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Education, Hetao College, Bayannur, Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China; 3Nanchong Central Hospital, North Sichuan Medical University, Nanchong, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Guihua Qin, Email [email protected]

Background: As the role of emotional intelligence has been increasingly explored, researchers generally agree that emotional intelligence is a better predictor of individual success. And fortunately, emotional intelligence is somewhat easily shaped. Schools are important microsites for the shaping of an individual’s emotional intelligence. Good teacher-student relationship contribute to the shaping and development of students’ emotional intelligence.

Objective: Based on the theory of developmental contextualism, the current study aims to identify the relationship between good teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence, and the mediating roles of students’ openness and emotional intelligence.

Methods: In this study, a total of 352 adolescents (11– 15 years old) from two schools were surveyed using the teacher-student relationship scale, big five inventory openness subscale, and emotional intelligence scale.

Results: Teacher-student relationship were positively correlated with students’ openness, empathy, and emotional intelligence. Teacher-student relationship positively predicted students’ emotional intelligence; students’ openness and empathy played a fully mediating role in teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence.

Conclusion: The closeness and supportiveness of the teacher-student relationship were positively related to students’ openness, empathy, and emotional intelligence were positively correlated.

Keywords: teacher–student relationship, openness, empathy, emotional intelligence, adolescents

Introduction

Emotional intelligence is defined as a construct comprising abilities relating to appraise and express emotions and using them for motivational and decision-making purposes.1 Emotional intelligence, also known as trait emotional intelligence, as measured by self-report measures (eg, personality questionnaires), contains a range of personality-related emotions and self-perceptions.2,3 This structure is adaptive because it provides the ability to effectively manage emotions and interpersonal relationship in a way that achieves goals better than the use of violence.3–5 According to the ability model, trait emotional intelligence usually comprises four abilities: recognition of emotions both in oneself and others, use of emotional information to facilitate cognitive decision-making, understanding the effects of emotions, and managing emotions in oneself and others.6,7 Previous studies have shown that emotional intelligence is negatively associated with internalizing problems, depression, and anxiety in adolescents;8,9 and positively associated with academic performance, health habits, well-being, aggression, and psychological adjustment in adolescents.10,11 Given the importance of emotional intelligence, the development of emotional intelligence in adolescents has been widely discussed.8–11

Teacher–Student Relationship and Emotional Intelligence

According to the person-context interaction theory of individual ability development, factors within the individual interact with the environment,12 and the school environment in which adolescents are placed may contribute to the development of emotional intelligence by influencing internal factors. Teacher-student relationship are a significant factor in the environment in which adolescents live.13,14 According to Goleman (1998), children learn early on how to manage their emotions from adult reactions and internalize them into their own unique emotional processing patterns. For students in the schooling phase, they can often learn to properly express and effectively manage their emotions through teacher feedback when interacting and communicating with teachers during school life, which may promote the development of their emotional intelligence.15 Empirical studies have also shown that the closeness and supportiveness of the teacher-student relationship promote the development of students’ emotional intelligence.16 Students who have a positive relationship with their teachers are more likely to receive the guidance and support they need for emotional development, including ways to identify and understand their emotions and the skills to deal effectively with their negative emotions, all of which contribute to the development of their emotional intelligence.16

It is worth noting that as the primary interpersonal relationship of adolescents, in a positive teacher-student relationship, the teacher is an ad hoc attachment figure with a haven and secure base function, which will positively impact the student’s emotional development.17,18 Especially in Eastern cultural contexts (eg, China), students and teachers are more likely to form teacher-student attachments because of the strong influence of Confucianism. For example, the traditional proverb “once a teacher, always a father”. It is to emphasize that students should treat their teachers with the same respect and care as their fathers, and teachers should treat their students with the same patience and instruction as their own children. In addition, at each stage of basic education in China (eg, elementary school, secondary school), students’ teachers rarely change. In elementary schools, for example, teachers who are identified from the time students enter the first grade will remain as teachers for the cohort until they graduate. Research in Eastern cultural contexts has shown that emotional attachments are easily formed between teachers and students due to the stability of the teacher-student relationship.18,19 It is one of the meaningful social relationship in students’ socialization process and has a profound impact on their emotional development. However, it has also been shown that emotional intelligence in students and teachers promotes higher quality teacher-student relationships (eg Xiang et al 2022).20 Since the research methods of both Xiang et al and our study used correlational research methods.20 Thus, methodologically neither study could account for the causal relationship between teacher-student relationships and students’ emotional intelligence. This is a limitation of using correlation research methods. Based on the above theories, we argue from a theoretical perspective that Chinese adolescents are used as a study to further illuminate the correlation between teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence.21

The Mediating Role of Empathy

Elevated levels of student empathy may be an inherent mechanism by which good teacher-student relationship promote the development of students’ emotional intelligence. Empathy is an individual’s ability to recognize others’ emotions, understand their emotional reactions and experiences, and respond appropriately.22,23 According to attachment theory, attachment is a strong emotional bond that develops between infants and early caregivers.24 This interpersonal interaction promotes the development of students’ empathic abilities.25 For example, developing infants are more able to respond to and share the emotional state of their primary caregiver if the primary caregiver, the infant’s object of attachment, is able to provide them with constant physical and psychological attention.26 Individuals often have multiple attachment figures and the degree of attachment to the same attachment figure varies from period to period.24,27 From early childhood to secondary school, as individuals spend more time in school and more time in teacher-student interaction, teachers gradually become another important object of attachment for students.18,19 Teachers have an important responsibility to develop good social citizenship and to promote the development of empathy and sociality in their students.19 Individuals in the schooling period interactions with teachers, teachers often guide them to identify the emotions of others and to understand the reasons behind others’ emotions and behaviors, which may facilitate the development of empathy in students.28 Empirical studies have similarly found that closeness and supportiveness of the teacher-student relationship are associated with students’ empathy.14,29

Emotional intelligence and empathy are related but distinct constructs.32 Specifically, empathy is often described as the ability to see the world through the eyes of others.22 Emotional intelligence, requires the ability to use this information to guide one’s thoughts and behaviors based on feeling and understanding the emotions of others.1 Bloom (2015) presented the spot light effects of empathy strongly suggesting that empathy is not the same as emotional intelligence.30 Bloom (2015) argued that empathy can prompt empaths to focus their attention on the target object of empathy and ignore other individuals who are not seen as empathic objects.30 However, individuals with higher emotional intelligence are more aware of the irrationality in their own emotions and will mobilize rationality to guide their thoughts and behaviors by controlling their own and others’ emotions, reducing the likelihood that they will behave irrationally.1,2 The correlation between empathy and emotional intelligence is mainly reflected in the fact that empathy is considered to be the basis of emotional intelligence.31,33 Based on the structure of emotional intelligence, emotional intelligence requires individuals to monitor their own and others’ emotions and feelings, and to use this information to guide their thoughts and behaviors by identifying and using it.1 The prerequisite for these abilities to be realized is the individual’s ability to have a high level of sharing and understanding of others’ emotions, ie, empathic ability.33 Therefore, it can be inferred from the structure of the two that enhancing empathic ability is to some extent conducive to emotional intelligence. Meerum Terwogt and Stegge et al similarly concluded that as empathy develops, individuals become more skilled in combining emotional knowledge to make sense of different social situations. Moreover, empathy increases an individual’s knowledge of emotions,34 including understanding the social consequences of emotionally expressive behaviors and managing emotional states.35 Highly empathic individuals can better manage their emotions to reduce the adverse effects of excessive empathy.36 In addition, individuals with high levels of empathy are also more likely to feel and understand emotions from the perspective of others, thereby increasing the accuracy of identifying others’ emotions. Empirical studies have also found that individual empathy positively relates to emotional intelligence.37,38 In summary, it can be deduced that the mechanism underlying the ability of teacher-student relationship to promote the development of students’ emotional intelligence lies in the fact that good teacher-student relationship promote increased levels of student empathy.

The Mediating Role of Openness

Based on Rogers’ personality theory, the teacher’s support, encouragement, and unconditional positive attention can then facilitate the development of openness in students’ personality factors and promote the formation of a sound personality.39 When teachers try to understand students’ interests, pay attention to their emotions such as fears and concerns, and give them motivation and support, this makes students feel that the teacher is working for their well-being and that they feel they are being cared for, helped and considered.40 Students will then follow the teacher’s example and actively promote the development of the positive elements of their own personality.40 Among the personality traits that openness is a positive, open-minded, and curious personality trait.41 According to Fung and Durand (2014), individuals with high levels of openness is imaginative, curious, and open to non-traditional ideas and values.42 Individuals with high levels of openness are better at seeking help and expressing their needs.43 Individuals with higher openness are more willing to try to change the status quo and actively solve problems, while individuals who lack openness will wait for opportunities and adapt to their environment rather than change the status quo.42 Closeness and supportiveness teacher-student relationship often create an atmosphere of positive interaction that makes adolescents more willing to express needs and increase interactions with others.40 This contributes to higher levels of openness in personality traits.

Empirical studies have shown that the openness factor in personality is closely related to the emotional intelligence of individuals.44–46 According to Kenneth Gergen’s theory of relational being, the human being is defined as a multi-being that carries enormous potential for action.47 The ability of these potentials to come into life at any given moment depends on the person with whom we are interacting.47 Through interpersonal interactions, these potentials may be developed or degraded.47 The ability to control, manage, and regulate emotions is constantly being constructed and rebuilt in interpersonal interactions.47 Individuals with higher levels of openness are more able to view interpersonal problems and dilemmas positively than those with lower levels of openness, and thus develop their potential for emotional intelligence in the process of trying to solve them. In summary, it can be inferred that Students’ openness may mediate the teacher-student relationship with students’ emotional-intellectual relationship.

The Mediating Roles of Openness and Empathy

Developmental contextualism is the theory that although plasticity decreases with age, it is maintained throughout a person’s life in personality and social development.48,49 The development of human personality and sociality is achieved through the continuous interaction between the individual and the context in which he or she is placed.48,49 The development of the individual is continuous.48 Individuals can be influenced by appropriate and well thought out education that leads to positive personality and social development.49 During adolescence, as students interact with teachers for longer periods of time, the teacher-student relationship becomes an important factor in the development of students’ personalities and sociality.50 When teachers and students have a good teacher-student relationship, teachers’ education will be smoother and students will be more willing to imitate teachers’ behaviors, attitudes, and values.17 In the face of frustration, a good teacher-student relationship is more conducive to teachers’ cultivation of students’ optimism in facing problems, their determination to tackle problems head-on, and their belief in exploring new solutions.17 In other words, a good teacher-student relationship is conducive to the improvement of students’ openness level. Because high openness is characterized by open-mindedness, optimism, and willingness to explore, it makes individuals with higher levels of high openness likely to have a higher potential to enhance empathy. When faced with interpersonal conflicts and distress, they are more able to stimulate their own potential, improve their own empathy level, understand others’ emotional experiences and share others’ feelings accurately.51 Claxton-Oldfield et al consider openness as a protective factor for empathy.52 Because openness represents imagination, emotion, and flexibility, empathy requires imagination and flexibility.53,54 Consistent findings from studies using questionnaires that openness positively relates to empathy.55,56 This higher empathy can help individuals recognize the limitations of their own irrational perceptions and thinking in problem solving. Compared to lower levels of empathy, higher levels of empathy lead individuals to capture more relevant information about others’ perspectives and emotions, which helps individuals to better guide their own thoughts and behaviors.22 The current study aims to further clarify the relationship between the teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence and the role of students’ openness and empathy in it. This is in order to better identify good pathways for developing students’ social skills such as empathy and emotional intelligence for their development.

The Aim of Present Study

This study aims to provide empirical evidence for understanding how schooling affects students’ personality and social-emotional competence development, thereby drawing educators’ attention to the teacher-student relationship. Accordingly, this study constructed a chain-mediated mediating model based on the Person-context interaction theory to examine the relationship between teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence and the role of openness and empathy. Based on the above literature review, the following hypotheses were proposed: (1) Teacher-student relationship in adolescents can positively predict emotional intelligence (Hypothesis 1). (2) Openness and empathy play independent mediating roles between teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence in adolescents, respectively (Hypothesis 2). (3) We predicted that openness personality and empathy played a chain-mediated mediating role between teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence in adolescents (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

Participants

This survey was conducted in Guiyang City, Guizhou Province, China, using a whole-group sampling method, and students in grades 5–7 were selected as the study population. A total of 370 adolescents were given questionnaires, and all were returned. After eliminating invalid questionnaires (missing values over 3%), 352 questionnaires were obtained. Among them, 188 were boys, 164 were girls, the youngest was 11 years old, and the oldest was 15, with a mean age of 12.38 (SD age = 1.16). The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of theDepartment of Psychology of Zhejiang Normal University approved the research protocol.

Procedures

Data collection began after obtaining the support of the classroom teacher in each classroom. All questionnaires were distributed and collected by the teachers who served as the computer course in the science curriculum. The computer teacher was chosen as the main test because local computer courses are evaluated only as interest courses and are not included in the assessment and evaluation system of student learning.

In the questionnaire distribution, firstly, the main test gave informed consent forms to the parents and the students themselves, and the formal questionnaire was administered to the students only if the students and their primary guardians signed the informed consent forms. Subsequently, with the students’ consent, the lead testers used the time of the activity class to fill out the questionnaire as a class. Before filling out the questionnaire, the participants were informed that their answers would be kept confidential and would not be accessed by anyone other than themselves. All students completed the questionnaire in less than 15 minutes. At the end of the task, each participant received a small gift.

Measures

Teacher - Student Relationship Scale

A student-rated teacher-student relationship scales developed by Zou et al was adopted.21 The teacher-student relationship scale comprised 23 items rated in four subscales: closeness, conflict, supportiveness, and satisfaction. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (entirely). Of these, closeness reflects students’ perceived emotional support provided by the teacher; supportiveness reflects students’ perceived instrumental support provided by the teacher; and satisfaction and conflict reflect students’ evaluations of the teacher, whether antagonistic or harmonious. Arguments and debates between teachers and students may allow students to perceive the existence of conflict between teachers and students, while being more satisfied with the relationship and grateful for the teachers’ diligent teaching. When there is a lack of interaction between teachers and students, conflict scores are lower and satisfaction may be higher in students’ evaluations. That is, the Satisfaction subscale and the conflict subscale may lead to distortion in the evaluation of the teacher-student relationship. We discovered this phenomenon in the pre-survey between the start of the official questionnaire distribution. Thus, we did not include the conflict subscale and satisfaction subscale in the formal questionnaire administration. The closeness subscale and the supportiveness subscale are able to reliably evaluate the teacher-student relationship in terms of teacher-student interaction behaviors. Both the supportiveness subscale and the closeness subscale had good reliability, and their Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.71 and 0.87, respectively.

Big Five Inventory Openness Subscale

The openness subscale of the Chinese version of the big five inventory revised by Wang et al, was used as a measurement instrument. The subscale has eight items and is scored on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (entirely), with higher scores indicating that the individual has a higher level of openness.57 The openness subscales have good reliability in both adolescent and university student populations.58,59 The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the openness subscale was 0.71.

Interpersonal Reactivity Index

Adolescent empathy was measured using the interpersonal reactivity index developed by Davis (1980).22 The scale includes four dimensions of perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress, each with seven questions and a score range of 1 (not at all consistent) to 5 (completely consistent). The Chinese version of the scale was revised by Rong et al, is widely used in the Chinese adolescent population, and has good reliability.60,61 According to some researchers’ suggestions, the two dimensions of perspective taking and empathic concern can represent cognitive and emotional empathy, respectively,57 so only these two dimensions were included in the analysis of this study. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for perspective taking and empathic concern were 0.75 and 0.59.

Emotional Intelligence Scale

The emotional intelligence of adolescents was measured using the Chinese version of the Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS) revised by Wang (2002).62 The scale consists of 33 items measuring four factors: emotion perception, self-emotional regulation, emotion management of others, and emotion utilization. A scoring range of 1 (completely inconsistent) to 5 (completely consistent) was used for each item. The scale applies to adults and adolescents.63,64 Among them, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for emotion perception, self-emotional regulation, emotion management of others, and emotion utilization were 0.64, 0.67, 0.77, and 0.71, respectively.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

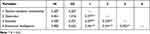

As shown in Table 1, the teacher-student relationship, openness, empathy, and emotional intelligence were positively correlated.

|

Table 1 Means (M), Standard Deviations (SD), and Correlations Among Variables |

Measurement Model

The measurement model for 8 latent variables were tested: closeness, supportiveness, perspective taking, empathic concern, emotion perception, self-emotional regulation, emotion management of others, and emotion utilization. This model revealed a good fit for the data, χ2/df = 1.5, CFI = 0.986, TLI = 0.978, RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.038(0.000~0.066), SRMR = 0.028. This provides a good premise for our next step of structural model construction.

Structural Model

A structural equation modeling analysis was conducted using adolescents’ teacher-student relationship as the independent variable and emotional intelligence as the outcome variable. This model revealed a good fit for the data, χ2/df = 2.47, CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.065(0.029~0.101), SRMR = 0.031. Teacher-student relationship positively predicted emotional intelligence (β = 0.454, p < 0.001).

A structural equation model analysis was conducted with adolescents’ teacher-student relationship as the independent variable, openness and empathy as the mediating variables, and emotional intelligence as the outcome variables, shown in Figure 1. This model revealed a good fit for the data, χ2/df = 1.32, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.985, RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.030(0.000~0.057), SRMR = 0.027. Using the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap test for mediation effects, the results showed (as in Table 2) that the 95% confidence intervals for all indirect paths did not include zero, indicating that the mediation paths were significant. In this model, the direct effect of teacher-student relationship on emotional intelligence was not significant (β = 0.092, SE = 0.059, 95% CI [−0.112, 0.247]), but the indirect effects of teacher-student relationship on emotional intelligence via openness and empathy were both significant (openness: β = 0.190, SE = 0.036, 95% CI [0.123, 0.263]; empathy; β = 0.136, SE = 0.061, 95% CI [0.054, 0.296]). Furthermore, openness and empathy played a significant chain-mediated mediation between teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence (β = 0.037, SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.010, 0.079]). The results of the present study analysis showed in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Standardized Indirect Effects from Teacher-Student Relationship to Emotional Intelligence |

To better understanding how much variance was explained independently by each construct in the current mediation model, we calculated the effect sizes (see Table 2). According to the method proposed in previous studies,65 the ratio of indirect to total effects for each construct was determined separately as the effect sizes. The results showed that the direct effect can only independently explain 20.24% of the effect of teacher-student relationship on emotional intelligence. However, the indirect effect can independently explain 79.76%. More precisely, the indirect effects of openness, empathy and openness and empathy jointly explained 41.71%, 29.85.96%, and 8.20% of the variance, respectively.

Discussion

Using Chinese adolescents as subjects, this study explored the relationship between teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence, and the mediating role of students’ openness and empathy. Our results showed that, as expected, students’ openness and empathy fully mediated the relationship between teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence.

Teacher–Student Relationship and Adolescent Emotional Intelligence

First, consistent with our expectation, the results showed that teacher-student relationship positively related to adolescents’ emotional intelligence. This finding was in accordance with a number of studies showing the association between teacher-student relationship and emotional intelligence in adolescents.17–19 In other words, positive teacher-student relationship are conducive to the development of students’ emotional intelligence. In a positive teacher-student relationship, adolescents have more opportunities to express their emotions. Through interaction and communication with teachers, students can often learn to properly express and effectively manage their emotions through feedback from teachers, thus promoting the development of emotional intelligence, supporting the theory of person-context interaction.12

The Mediating Role of Empathy

Second, students’ level of empathy plays a mediating role in the teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence. This is consistent with previous research findings that closeness and supportiveness of the teacher-student relationship are associated with student empathy.14,29 This supports attachment theory. Because individuals often have multiple attachment objects and attach to the same attachment object to different degrees at different times in their development.24,27 From early childhood to secondary school, teachers gradually become another important object of attachment for students as individuals spend more time in school and more time in teacher-student interactions.18,19 Teachers have the responsibility to promote the development of empathy and sociality in their students and to develop good social skills.19 In student-teacher interactions, teachers often guide them to identify the emotions of others and understand the reasons behind their emotions and behaviors, which may contribute to the development of students’ empathy skills.28 Current research has also found empathy to be related to emotional intelligence. This is consistent with the results of previous studies. Meerum Terwogt and Stegge et al suggest that as empathy develops, individuals become more proficient at incorporating emotional knowledge to make sense of different social situations. In addition, empathy increases an individual’s understanding of emotions,34 including understanding the social consequences of emotionally expressive behaviors and managing emotional states. Highly empathic individuals can better manage their emotions to reduce the negative effects of over-empathy.

The Mediating Role of Openness

Third, students’ openness plays a mediating role in teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence. The teacher-student relationship was significantly associated with students’ openness. This is consistent with the results of previous studies.44–46 Again, this supports Rogers’ theory of personality.39 Teachers’ support, encouragement and unconditional positive attention can promote the development of openness in the personality factors of students and the formation of a sound personality.39 When teachers try to understand students’ interests, attend to their emotions such as fears and concerns, and give them motivation and support, this makes students feel that the teacher is working for their well-being and that they feel cared for, helped and considered, and that they are following the teacher’s example.40 This facilitates an increased level of openness, including insight into the outside world, a more open-minded student with a more optimistic attitude, the courage to explore dilemmas, and reflection on failure. Because of the characteristics that openness has, it is thus highly predictive of emotion perception, emotion understanding, and emotion utilization.44–46 The current study likewise found that students’ openness was positively correlated with their emotional intelligence. This result also supports Kenneth Gergen’s theory of relational being. The human being is defined as a multi-being that carries enormous potentials for action.47 Through interpersonal interactions, these potentials may be developed or degraded.47 The ability to control, manage, and regulate emotions is constantly being constructed and rebuilt in interpersonal interactions.47 Individuals with higher levels of openness are more able to view interpersonal problems and dilemmas positively than those with lower levels of openness, and thus develop their potential for emotional intelligence in the process of trying to solve them.

The Mediating Roles of Openness and Empathy

Forth, current research has found that student openness and empathy play a fully mediating role in the teacher-student relationship and in students’ emotional intelligence. This suggests that the mechanism underlying the contribution of good teacher-student relationship to the development of students’ emotional intelligence may be due to the fact that teacher-student relationship increase students’ levels of openness and empathy, supporting the theory of developmental contextualism. Developmental contextualism is the theory that contexts shape the personality of an organism. The interaction between the individual and the environment (eg, interpersonal interaction, physical environment) during the developmental process results in a gradual formation of personality.48,49 Adolescents who feel more intimate and supportive of teacher-student relationship in the school environment will facilitate the development of their internal positive qualities. Specifically, adolescents with positive teacher-student relationship are more likely to develop openness by engaging in interactions in the school environment that focus on sharing and collaborating. Openness adolescents are typically more imaginative and flexible,43 are adept at seeking help and expressing needs in a wide range of interpersonal activities,40 and are more likely to develop high levels of empathy. It is evident that the results of this study support the idea that teacher-student relationship as an environmental factor can facilitate the further development of students’ intrinsic potential for empathy, openness, and emotional intelligence.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The current study found that teacher-student relationship positively predicted students’ emotional intelligence and found that students’ openness and level of empathy were intrinsic mechanisms, supporting the theory of developmental contextualism. It is worth noting that there are still shortcomings in this research. First, the current study used a cross-sectional experimental design, which was only able to find correlations between teacher-student relationship and students’ emotional intelligence, empathy, and openness, but could not reveal the causal relationship. The follow-up study can further test the results of the current study by using a follow-up study to find out whether students’ emotional intelligence, empathy level, and openness level change with the change of individual teacher-student relationship. However, the current study still has some value and significance. Emotional intelligence, as an important social competence, has received a lot of attention and focus from parents and schools. This research has helped schools and parents find viable ideas for developing students’ emotional intelligence. The development of students’ openness and empathy is promoted through the enhancement of teacher-student relationship, which in turn improves students’ emotional intelligence and facilitates the development of students. Second, the current study conducted data collection from March to June 2022. Affected by the epidemic (Covid-19), all subjects’ face-to-face interactions with the instructor were compromised. For almost a semester (January 2020 to May 2020), students did not interact with teachers offline. Thus, all participants in our study had relatively shorter teacher-student relationship with their teachers compared to those during the non-epidemic period. Yet even when affected by the epidemic, the teacher-student relationship still had an impact on students’ emotional intelligence. Third, the attitudes and beliefs of students’ parents toward teachers may influence students’ evaluations of teacher-student relationship. Subsequent research may further control for student parents’ relationship and attitudes toward teachers when exploring issues related to teacher-student relationship in order to more accurately assess students’ perceived teacher-student relationship. Finally, the current study explored the effects of teacher-student relationship on students’ emotional intelligence only in the Chinese cultural context. Influenced by the education system, some countries and regions may change teachers twice a year. Follow-up research could further investigate the effects of teacher-student relationship on students’ emotional intelligence in areas with frequent teacher turnover to further demonstrate the stability of the current study’s findings.

Conclusion

Current research suggests that good teacher-student relationship positively predict students’ emotional intelligence and that increased levels of student openness and empathy are intrinsic mechanisms that support the theory of developmental contextualism.

Data Sharing Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology of Zhejiang Normal University approved the research protocol.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been provided by the patients/legal guardians.

Acknowledgment

Shuwei Lin is a co-first author.

Funding

The authors thank the participants who participated in the study. This research is supported by the Open Research Fund of College of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University (No. jykf20068).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Salovey P, Mayer J. Emotional intelligence imagination, cognition, and personality. Imagin Cogn Pers. 1997;9(3):89–90.

2. Petrides KV, Pita R, Kokkinaki F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br J Psychol. 2007;98:273–289. doi:10.1348/000712606X120618

3. Alegre A, Pérez-Escoda N, López-Cassá E. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and personality. Is trait EI really anchored within the big five, big two and big one frameworks? Front Psychol. 2019;10:866. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00866

4. Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ for Character, Health and Lifelong Achievement. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1995.

5. Brackett MA, Rivers SE, Shiffman S, Lerner N, Salovey P. Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:780–795. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

6. Trigueros R, Aguilar-Parra JM, Cangas AJ, Bermejo R, Ferrandiz C, López-Liria R. Influence of emotional intelligence, motivation and resilience on academic performance and the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2810. doi:10.3390/ijerph16162810

7. Mayer JD. Emotion, intelligence, and emotional intelligence. In: Forgas JP, editor. The Handlook of Aftect and Social Cognition. Mah-wah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001:410–431.

8. Fernandez-Berrocal P, Alcaide R, Extremera N, Pizarro D. The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Dif Res. 2006;4(1):16–27.

9. Resurrección DM, Salguero JM, Ruiz-Aranda D. Emotional intelligence and psychological maladjustment in adolescence: a systematic review. J Adolesc. 2014;37(4):461–472. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.012

10. Ferrando M, Prieto MD, Almeida LS, et al. Trait emotional intelligence and academic performance: controlling for the effects of IQ, personality, and self-concept. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2011;29(2):150–159. doi:10.1177/0734282910374707

11. García-Sancho E, Salguero JM, Fernández-Berrocal P. Relationship between emotional intelligence and aggression: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(5):584–591. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.007

12. Magnusson D, Stattin H. Person-context interaction theories. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 1998:685–759.

13. Liberante L. The importance of teacher–student relationships, as explored through the lens of the NSW Quality Teaching Model. J Stud Eng. 2012;2(1):2–9.

14. Castillo R, Salguero JM, Fernández-Berrocal P, Balluerka N. Effects of an emotional intelligence intervention on aggression and empathy among adolescents. J Adolesc. 2013;36(5):883–892. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.001

15. Goleman D. Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books; 1998.

16. Tao L, Li Z. Overseas research on teacher-student relationships. Int J Comp Educ. 2016;314(3):61–68.

17. Ju X, Liu X, Fang X. Research on adolescent parents and peer attachment in relation to self-esteem and social adaptation. Psychol Devel Educ. 2011;27(2):174–180.

18. Zhang L, Zhang S, Ning W. Path analysis on teacher-child relationship and peer relationship influenced adolescents’ self-esteem. J Health Psychol. 2009;17(11):1378–1381.

19. Wanng Y. The Research of Secondary School Students and Teachers Attachment, Emotional Intelligence and Adaptation Orientation of Mental Health. Shannxi Normal University, Master Dissertation; 2014.

20. Xiang D, Qin GH, Zheng XW. The influence of student-teacher relationship on school-age children’s empathy: the mediating role of emotional intelligence. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:2735–2744. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S380689

21. Zou H, Qu ZY, Ye Y. Student-teacher relationship and school adaptation of primary and middle school students. Psychol Devel Educ. 2007;4:77–82.

22. Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):113. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

23. Cuff BM, Brown SJ, Taylor L, Howat DJ. Empathy: a review of the concept. Emot Rev. 2016;8(2):144–153. doi:10.1177/1754073914558466

24. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Voll. 1. Attachment.

25. Marci CD, Orr SP. The effect of emotional distance on psychophysiologic concordance and perceived empathy between patient and interviewer. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2006;31:115–128. doi:10.1007/s10484-006-9008-4

26. Field T, Healy BT, Goldstein S, Guthertz M. Behavior-state matching and synchrony in mother-infant interactions of nondepressed versus depressed dyads. Dev Psychol. 1990;26(1):7–14. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.1.7

27. Huang G, Zhang Y. Advances in the research of attachment. Psychol Devel Educ. 2003;19(3):92–96.

28. Pan Y, Xiao Y, Hu Y, Liu G, Li Z. Effects of secure attachment on empathy and altruistic behavior. Adv Cogn Psychol. 2019;27(12):2077–2083.

29. Petrides KV, Furnham A. Trait emotional intelligence: behavioral validation in two studies of emotion recognition and reactivity to mood induction. Eur J Pers. 2003;17:39–57. doi:10.1002/per.466

30. Bloom P. Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. Random House; 2017.

31. Meerum Terwogt MM, Stegge H. The development of emotional intelligence. In: Goodyer IM, editor. The Depressed Child and Adolescent. New York:: Cambridge University Press; 2001:24–45.

32. Fernández-Abascal EG, Martín-Díaz MD. Relations between dimensions of emotional intelligence, specific aspects of empathy, and non-verbal sensitivity. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1066. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01066

33. Olderbak S, Wilhelm O. Emotion perception and empathy: an individual differences test of relations. Emotion. 2017;(2017(17):1092–1106. doi:10.1037/emo0000308

34. Qualter P, Barlow A, Stylianou MS. Investigating the relationship between trait and ability emotional intelligence and theory of mind. Br J Dev Psychol. 2011;29(3):437–454. doi:10.1348/026151010X502999

35. Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Emotional intelligence new ability or eclectic traits? Am Psychol. 2008;63(6):503–517. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503

36. Hajibabaee F, Farahani MA, Ameri Z, Salehi T, Hosseini F. The relationship between empathy and emotional intelligence among Iranian nursing students. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:239–243. doi:10.5116/ijme.5b83.e2a5

37. Austin EJ, Evans P, Magnus B, O’Hanlon K. A preliminary study of empathy, emotional intelligence and examination performance in MBChB students. Med Edu. 2007;41(7):684–689. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02795.x

38. Azadeh SA, Mahmoodi R. Identification the problems of teacher-student relationships from the viewpoints of primary school teachers: a phenomenology study. Rev Teach. 2020;8(3):74.

39. Rogers CR. A Way of Being. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 1995.

40. Ulug M, Ozden MS, Eryilmaz A. The effects of teachers’ attitudes on students’ personality and performance. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:738–742. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.144

41. Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(6):1246–1256. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246

42. Fung L, Durand RB. Personality Traits. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;49(244):115–118. doi:10.1002/9781118813454.ch6

43. Qiang J. A study on the relationship between Gratitude, personality and Social support in college students. J Sichuan Vocat Tech Col. 2016;06:21–23. doi:10.13974/j.cnki.51-1645/z.2016.06.005

44. Dehghanan H, Rezaei M, Rezaei M. A study on effect of big five personality traits on emotional intelligence. Manag Sci Lett. 2014;4(6):1279–1284. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2014.4.016

45. Ali R, Bukhari SKUS, Muhammad S. The Importance of IPIP five factor personality traits in prediction of University Students’ Emotional Intelligence. Pakistan Soc Sci Rev. 2021;5(2):556–569. doi:10.35484/pssr.2021(5-II)44

46. Nawi NHM, Redzuan M, Hashmi SI, Din A. Big-Five personality traits and its effect on emotional intelligence among public school personnel in Malaysia. Sou Asia Psychol J. 2015;3:1–14.

47. Gergen KJ. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Oxford University Press; 2009.

48. Lerner RM. A “goodness of fit” model of person-context interaction. In: Magnusson D, Allen VL, editors. Human Development: An Interactional Perspective. New York: Academic Press; 1983.

49. Lerner RM. On the Nature of Human Plasticity. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984.

50. Lei R, Suo Y, Li C. Relationship between mental health and family function, teacher-student relations and five-factor personality of adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;19(5):687–689.

51. Dong QF. Analysis on the influence mechanism of open personality on entrepreneurial ability for university students. J Nanjing Med Univ. 2020;4:26–30+91.

52. Claxton-Oldfield S, Banzen Y. Personality characteristics of hospice palliative care volunteers: the “big five”and empathy. Am J Hosp Pal Med. 2010;27(6):407–412. doi:10.1177/1049909110364017

53. Shamay-Tsoory SG. Empathic processing: its cognitive and affective dimensions and neuroanatomical basis. Soc Neurosc Emp. 2009;2009:215–232.

54. Yan Z, Hong S, Liu F, Su Y. A meta‐analysis of the relationship between empathy and executive function. Psych J. 2020;9(1):34–43. doi:10.1002/pchj.311

55. Svenson A, Guillen P. The links between intelligence, personality, and theory of mind in an adult sample; 2020.

56. Koivisto M, Virkkala M, Puustinen M, Aarnio J. Open and empathic personalities see two things at the same time: the relationship of big-five personality traits and cognitive empathy with mixed percepts during binocular rivalry. Cur Psychol. 2021;2021:1–11.

57. Wang MC, Dai XY, Yao SJ. Development of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory (CBF-PI) III: psychometricProperties of CBF-PI Brief Version. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;04:454–457. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2011.04.004

58. Chen HB, Liu J. The relations between family socioeconomic status and teenagers’ wisdom: the mediating roles of positive parenting style and openness personality. Psychol Devel Educ. 2018;05:558–566. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2018.05.06

59. An Y, Huang Q, Gu W, Fu H. Effects of openness personality on posttraumatic growth: moderated mediating effect. Stud Psychol Beh. 2017;15(6):815–823.

60. Rong X, Sun BH, Huang XZ, Cai MY, Li WJ. Reliabilities and validities of Chinese version of interpersonal reactivity index. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2010;18(2):158–160.

61. Liu JY, Yang CL, Qu ZY, Wu N. The relationship between empathy and aggression in elementary school students. Mental Health Educ Prim Second Sch. 2021;10:7–12.

62. Wang CK. The relationship between parental rearing styles with general self-efficacy and emotional intelligence in high school students. Chin Mental Health J. 2002;16(11):781–782.

63. Zhang QY, Zhang W, Yue SH, Wang CK. The relationship between emotional intelligence and coping style in middle-school students. Chin Mental Health J. 2004;08:544–546+543.

64. Huang Y, Lv A, Wang L, Shi J. Validation of the emotional intelligence scale. Acta Sci Nat Univ Pekin. 2008;44(6):970–976.

65. Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi:10.1037/a0022658

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.