Back to Archived Journals » Patient Intelligence » Volume 8

The lived experience of patients regarding patients' rights practice at hospitals in Amhara Region, northern Ethiopia

Authors Mekonnen AB, Enquselassie F

Received 6 January 2016

Accepted for publication 31 March 2016

Published 19 May 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 47—55

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PI.S103761

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Adugnaw Berhane,1 Fikre Enquselassie2

1College of Health Sciences, Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, 2School of Public Health, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Background: There are a number of different international guidelines promoting the practice of observing patients’ rights in the health care service. Patients experience greater satisfaction in the health care service when their rights are protected. The purpose of this study was to examine patients’ experiences regarding their rights in hospital settings in northern Ethiopia.

Patients and methods: Data were collected using semistructured interviews of 22 patients, who have had experience of health care service in the hospital setting. The patients were selected from the outpatient and inpatient departments of referral and district hospitals in northern Ethiopia. The interview data were tape-recorded, transcribed, translated, reviewed, and analyzed using a phenomenographic approach. Categories of descriptions were constructed based on the patients’ conceptions and ways of understanding the phenomenon of patients’ rights practice.

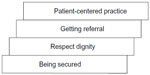

Results: The findings revealed four main qualitatively different ways of understanding patients’ rights practice from the patients’ perspective. These main categories of description were patient-centered practice, being secured, respecting patients’ dignity, and getting referral.

Conclusion: The different conceptions of patient rights give us a deeper understanding of how patients may experience patients’ rights practice. The result provides a foundation for developing health care practice that equips the patient with a positive experience, thus contributing in drafting patients’ bill of rights in the local context.

Keywords: patient rights, phenomenography, hospital health care, patient experience

Introduction

Given the preface of the human rights declaration introduced by the United Nations in 1948, patients’ rights legislations have been accepted in many countries worldwide.1 The constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO)1 focuses on relationships between health care and human rights. It affirms that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of religion, race, political belief, social, and economic condition”.2 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in 1966 articulate the aptness of human rights and health to the well-being of individuals as well as the family.3,4 The Declaration of Alma Ata5 of “health for all” in 1978 with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion6 in 1986 further squeezed the need for social and economic inputs to improve the health well-being of the population. Therefore, there is a deep affiliation between human rights and health.

Many declarations define the importance of the right to lead a healthy life.7–9 The Lisbon Declaration of World Doctors Association, for instance, was the first study to look at patients’ rights.10 The WHO published a detailed document (A Declaration on the Promotion of Patients’ Rights in Europe) stating that the principles and strategies of patients’ rights in Amsterdam have all drawn up legislation covering patients’ rights.11 Concerns related to respect for patients’ values, choices, and preferences are becoming more multifaceted. Patients’ expectations are higher, and they want the best. They want to actively participate in decision making and wished for treatments or procedures and their different options.12

Many countries have guaranteed patients’ rights to process for resolving dissatisfactions with health care providers.13,14 In health care services, the quality of care, such as patient satisfaction, empowerment and treatment, and access to health personnel, is found to be important to patients. Furthermore, regular sources of care and convenient services are key issues in medical care services.15–17

In giving effective care, the patient generally demands their rights, while the hospital is responsible for fulfilling this particular expectation.6 The charter of the patient’s rights is a protection of human rights, with the assumption to preserve patient’s honor and dignity and to ensure that the patient receives a good quality of care in illness situations, specifically in medical emergencies, without any age or sex discrimination and irrespective of his/her financial position, life, and health. Patients’ rights charter claims that the basic rights of the patients who receive care from health institutions need to be explained.18 In addition, the WHO has also presented solution that mostly involve active participation by the service providers and service recipients in formulating health care service policy.19

The research group on citizens’ empowerment and patients’ rights by WHO recommended that every state should articulate its priorities and concerns based on its own social and cultural needs to protect and promote patients’ rights.11,18 Many countries have recognized health care organization charters or regulations for patients’ rights, and have stated and applied them to attain patients’ satisfaction.20 Hospitals may adapt routine policies for informing customers about their rights for safe, effective, and efficient health care provision.21

The government of Ethiopia as mentioned in the constitution of Article 41 under Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that every Ethiopian citizen has the right to have equal access to publicly funded social services.22 The Ethiopian Government is committed to ensuring access of all people to quality health care services as indicated in the Health Sector Development IV of Ethiopia.23 Health care is a major social service sector in Ethiopia. There have been some structural changes in the health sector regarding patients’ value judgments, health care centers, and health personnel. There have been changes regarding patients’ value judgments, from health care providers previous sense of gratitude and respect to health care, based on the interests of the patient. Patients need to communicate with the health care provider and participate in decisions. Patients may complain, and provide their feelings of dissatisfaction with the service, health care centers, and health care providers.24 To understand the current patient value judgments, research on patients’ conception of patients’ rights practice is essential for the understanding and implementing of health care service according to conceptions on their rights thus it may contribute to improve patients.18 Therefore, this study was conducted to examine patients’ experience in the practice of their rights in the hospital setting and to explore different categories of meaning in a hierarchical order.

Patients and methods

Settings and participants

The study was conducted in the northern region of Ethiopia. There were a total of 17 functional public hospitals in the region which served a population of 17,214,056, of whom 8,636,875 were male and 8,577,181 were female. Urban inhabitants’ number estimated was 2,112,220 or 12.27% of the population. The population receives health services mainly from public health institutions. During the time of data collection, ~296 physicians, 1,343 health officers, and 9,593 nurses served the people of the region creating high provider-to-population ratios.25 Public hospitals service people in outpatient and inpatient departments. The referral hospitals provide specialist health care services at departments, such as medical, surgical, gynecological, and pediatric, using specialists. The district hospitals provided general health care services with general practitioners or other health care practitioners in case there were shortages of general practitioners.

Data were collected from nine (four referral and five district) public hospitals. We interviewed adult patients who were seeking health care in the outpatient and inpatient departments or medical or surgical care, that were familiar with the hospital’s health care environment so that they were able to explain their experiences. Participant inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: age >18 years, differ by sex, residence, educational status, and current experience in the outpatient and inpatient departments.. Twenty-two patients were chosen using maximum variation sampling technique by fulfilling the criteria mentioned, so as to get a wide variety of conceptions by capturing as many aspects as possible of the phenomenon under study. Table 1 shows respondents’ demographic characteristics in random order.

Design

The study focus was to describe the variation in how patients conceive, understand, and conceptualize the phenomenon of patients’ rights practice. Hence, a qualitative design with a phenomenographic approach was chosen.26 Phenomenography has revealed a qualitative research approach for describing the lived experience of the research participants. The application of phenomenography is relevant in understanding patients’ experiences, which is the main research aim of this study. In other words, it is usually applicable to explore patients’ experiences of their illness and health-service-related experiences.27

Phenomenography takes up a nondualistic ontology which assumes a person and a phenomenon to have an inseparable relationship. There are no two worlds: the real, objective world, on one hand; and a subjective world of mental representations, on the other hand. There is only one real existing world, that is experienced and understood in different ways by human beings, which is simultaneously objective and subjective.28 “The only world that human beings can communicate about is the world as experienced”.29 The epistemological stance of phenomenography assumes that experience is described as an internal relationship between human beings and the world. Hence, phenomenography considers that knowledge is constituted through internal relationships between people and the world, it is conceptualized as a human–world relationship.28 People differ in experiencing the surrounding world, and these differences can be related, described, and understood by others. The conception may differ from within the same person, or from one person to another, as different aspects of the phenomenon are conceived depending on the whole in relation to a given context. Phenomenography gives emphasis to a way of examining a collective human, rather than individual perspective of a phenomenon. In phenomenography, there are distinctions between what something really is; that is, the actual phenomenon which is said to be the first-order perspective, and how something is conceived to be and how a phenomenon is conceptualized by the people, which is said to be the second-order perspective.28 Therefore, this study focuses on how patients practice their rights as conceived by those who seek health care in the hospital.

Data collection

We used a semistructured interview data collection technique, since it is an appropriate method in phenomenography.28 Interviews were conducted by the principal author from August to October 2014. All interviews were started with an open-ended question, for example, “Could you please tell me what patient rights means to you in hospital health care?” Based on the immediate understanding of what the patients were trying to express, subsequent prompts were used to elicit and clarify the concept under study by using expressions, such as “how…” and “can you tell me more…”. The suitability of the question was checked among patients who seek health care in the inpatient and outpatient departments. The interviews were conducted in a safe room in the hospital and lasted for 30–45 minutes. The interviews were conducted using the local Amharic language, audiotaped, and later transcribed verbatim and then translated to English.

Data analysis

The data analysis techniques used six major steps.28 Familiarization phase was the first step, meaning that the interviews were read and reread by the researcher to gain the overall idea of the data and to correct errors in the transcripts. The second step involved transferring meaningful responses from data into meaningful statements/description codes. The third step contained a preliminary grouping or classification of similar meaningful statements. The fourth step was a preliminary comparison of categories, attempting to establish borders between the categories. This is a phase that sometimes entails revision of the preliminary groups. The fifth step consisted of naming the categories to emphasize their essence. The last step is a contrastive comparison of categories, which contains a description of the unique character of every category as well as a description of resemblances between categories. In this step, through interaction between the parts and the whole, based on similarities and differences, four descriptive categories emerged. An iterative process was used throughout the data analysis to check interpretations against the texts and the descriptive categories. Hence, a continual process of iteration between a focus on the whole and the parts was used to check on the interpretation until the descriptive categories that emerged from the data were found to be mutually exclusive. According to Marton and Booth,28 the descriptive categories are used to form the “outcome space” showing the whole of the findings (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Patients understanding of patients’ rights practice – the outcome space. |

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia). In addition, consent from the Amhara Regional Health Bureau and the respective hospital administrator was also sought. Verbal informed consent was used to obtain permission from the participants. Participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. No personal identifiers or names of participants were used at any point during the data collection, reporting, and dissemination of results. Each quotation was assigned by pseudo-identifiers to ensure confidentiality.

Results

In this study, four different main categories of patients’ conception on patients’ rights practice were extracted. Patients conceived patients’ rights practice as patient-centered practice, being secured, respect patients’ dignity, and referral. The main categories were explained by different subcategories (Table 2). The categories, which are supported by interviews with the participants, are described, and finally the findings are presented as a whole.

| Table 2 Categories and subcategories |

Patient-centered practice

The patient-centered practice category of patients’ rights practice comprises; attentive to patients’ concerns, which is a way of understanding patient needs, and participation in treatment procedures that put in shared decision making.

Attentive to patients’ concerns

Some participants described that health care providers did not listen to patients’ voice. Patients felt that some health care providers rejected their complaints and took their own actions. They described that health care providers did not give attention to their questions and preferences in their treatment. One participant stated:

I wanted to urinate but I have a catheter. I do not have knowledge how to use it…. I asked frequently “please come soon I am suffering” but they did not give attention to me…at that time I was very upset. They were working their own personal work. (Participant 7)

But other participants described that some health care providers were eager to know the patients’ situation. Patients experienced that their questions were listened to by the health care providers. Furthermore, patients appreciated their efforts to give the care that they wanted though they were busy. One participant expressed:

The health professional has talked to me about my personal matters and I responded to him. I have asked him and he responded to me. Despite him being busy; I appreciate his effort in listening to my questions and his friendly approach. (Participant 2)

Participation in treatment procedures

Patients considered that it is important to be engaged in a discussion during the rendered care, and for the details to be shared with them. In their opinion, decisions should be taken in an atmosphere of mutual understanding that could enable them to enhance their situation.

Some patients experienced that their views were acknowledged during the care provision by health care providers. They experienced that the health care provider gave them relevant information to their situation and on what was going on around them. Furthermore, some patients were asked questions related to their illness. Their smooth relationship with the health care provider builds trust, and this led to continuous discussions related to their health condition. They expressed that their conversation with the health care provider created a wider context for further discussions and mutual understanding on treatment procedures. One participant stated:

A health care provider and I were discussing my illness and treatment procedures…and reached a common understanding. While the doctor orders something to be done, I have to perform it after we arrived at a consensus on treatment procedures. (Participant 16)

Some patients, on the other hand, expressed that they were not participating in the care they received. They were not invited to ask questions since the health care providers were not in the position to answer questions. Furthermore, patients described that care providers use technical (medical) terms during their communication. Patients did not understand some of the medical terminology that health care providers used when talking to them. One participant described:

At the beginning, he (the health care provider) asked the symptoms of my illness, and then he observed some of my body parts through his hands. He did not tell me the diagnosis but I asked the doctor what my health problem would be? He responded with vague words that he guessed the problem to be related with my lung. But I didn’t understand him. You know why? It was difficult to grasp and understand what the health provider was explaining about. (Participant 8)

Being secured

In this descriptive category, patients’ rights practice as being secured, the patients conceived patient rights as a way of real patient–provider relationship, to be protected from any loss of privacy, and keeping patient information secret.

Keeping their privacy

Patients conceived being secure as privacy. Patients may not want to be seen in a way that might expose them during consultation or physical examination. They expected that their private parts should be protected from other health care providers, patients, and others during consultation and physical examination. Patients expected that the concern during consultation and physical examination be about them and the health care provider. There is no need for interferences and being exposed from other sides. One participant stated that:

I do not want to be seen by others…I believe that patients including myself, would like control of other people’s perceptions. (Participant 13)

Privacy is related with many areas in the care and health condition of the patient. It comprises anything related to social problems, relationships, personal feelings, and any other things related to the patient in the health care continuum. Patients wanted to be in their own, single room that could be silent and not to be exposed to other people. One participant expressed:

It is very important and I would like to be in a single room so I can relax…you know being in a single room means you can freely discuss private things with your family. (Participant 5)

Keeping patient information secret

Patients conceived patient rights as keeping patient information secret. Patients give their information to the health care provider. Patients did not want to disclose their identifiable information to others without their permission. They may not tell patients personal information to their close friends or relatives. Patients do not want their private information to be shared with those health care providers who are not directly involved for the care, or other patients and people in community. They described that they tell their health care providers because they trust them. Hence, private information needs to be protected. One participant expressed:

When patients get a health problem and go to the hospitals for treatment, they (patients) will tell their secrets to the doctor. Do you know why patients tell secrets to the doctor? Patients trust health care providers. Therefore, the doctor should keep the secret and not tell their problems to others. (Participant 19)

Respect their dignity

In this category, patients conceived patient rights as being treated as a person and respecting their independent capability.

Treated as a person

The patients conceived patient rights to be treated as a human being when they need medical care. Patients described that their views should be valued. They need to be understood and require confirmatory remarks. Patients need to be treated equally regardless of their disease status, residence, educational status, age, or sex. Patients do not like to be discriminated against but served equally. One participant expressed:

Since we are human beings, we have equal rights to get treatment and consultation… the staff are so good to some patients….and I also expect the same kind of treatment and support….but I thought it has to be due to, he/she (the other patient) is from urban and well educated. (Participant 7)

Respect their independent capability

Patients described patient rights in terms of respecting their independent capability. Patients want to be seen as the person that they were, having the capacity to work and being healthy. Patients experienced different health problems while coming to the hospital for care. They may have a damaged body in case of physical harm, or inability to carry out their work in case of mental or social problems. In this case, they may lose their previous capability. For example, one participant described:

I experienced unpleasant feelings when I got sick. I was no longer able to cope and have become dependent on physical aids. The physician realized I was in that situation, and advised me to be psychologically strong. Then, I was really optimistic and I do good take care of myself. You know why? I was so eager to be seen as a person as healthy as before. (Participant 11)

Getting referral

In this category, patients conceived that patients’ rights practice might extend to getting a referral; in this regard, patients perceived that an experienced health care provider might provide them better diagnosis and treatment.

Patients are keen to get better treatment in the hospital they visited. They anticipate being seen by an experienced health care provider who is famous in the hospital. Patients believed that experienced health care providers are skillful and could easily understand them and better know their health problem. One participant described:

Oh, I prefer to be treated by doctor M (the name of the doctor). He is an experienced health care provider. He knows the details of my health problem well, so I wish I had to be treated by him. (Participant 15)

But, some patients described that most health care providers influenced their views concerning health care provider choice, either by disagreeing with the question or having no ability to refer to the named health care provider. This restriction of internal referral to a chosen health care provider is a concern for most patients as they perceived that their recovery is better with the named health care provider. One participant stated:

In this hospital, Dr N (the name of the doctor) is the best individual, who behaves well. As a result, patients prefer him. So I witnessed that most patients, who had been treated by him were recovered from their illness. If referrals are allowed based on patients’ choice, most patients, I think, could choose him. But you can’t do that since health care providers have restricted us. (Participant 4)

The outcome space

The outcome space of the study showed a hierarchical relationship between the four main descriptive categories (Figure 1). It was interpreted to represent patients’ collective understanding of patients’ rights practice. The findings indicate that patient-centered practice is a comprehensive way of illustrating patients’ rights practice in the hospital setting. Patient-centered practice interpreted patients as a center of health care practice. This understanding aims at making patients have a positive experience of health care and maximizing patient satisfaction, positioned as being the core of patients’ conception of patients’ rights practice. Considering patients at the center of health care practice is the key component in their rights practice as most patients participate in their own care. Making patients converse with the health care provider and acknowledging patients’ views create a better health care provider–patient relationship. It also initiates discussion and shared decision making. Patient-centered practice was immediately supported by getting referral in practicing patient rights. Patients considered patients’ rights practice that was aimed at treatment by the reputable health care provider. Patients needed internal referral within the hospital or external referral to the hospital to get a better diagnosis and treatment. This happens when patients are participants in health care, and the health care providers are attentive to patients’ concerns. Patients’ rights practice in terms of respecting dignity, and being secured, was positioned at the lowest level in the outcome space. patients’ rights practice as being secured was expressed in the form of keeping their privacy during consultation or physical examination. It was also described as their information was not disclosed to others unless they permit it. This view was mainly associated with respecting the patient as a person and contributes to patient participation, thus closely linked to respecting their dignity. Patients’ rights practice in terms of respecting patients’ dignity was described as patients’ views were valued as a human being and to not be discriminated in spite of their different characteristics. Furthermore, despite their illness, patients want to be seen as the person that they were before, having the capacity to work and being healthy. The interplay between patients’ rights practice conception as being secured and respecting dignity makes patients at the center of health care and closely links with getting referral for a better diagnosis and treatment in and/or out of the hospital. This was also considered as the constituent of patient-centered practice, as these categories put patients first and value their views.

Discussion

The finding of this study shows a considerable variation in the patients’ conception of patients’ rights practice in hospital setting. The study entails patients’ conceptions of their rights in different ways. Patients described diverse views in practicing patient rights in the hospital health care that falls under the following categories: patient-centered practice, being secured, respecting patients’ dignity, and getting referral. Different conceptions of patient rights in the study context are important since rights determined from perspectives in a social context,30 and everything that encompasses is considered as patients’ rights.31

The patients in this study envisaged that patient-centered practice is the main category that patients conceived as a patients’ rights practice. Patients described the care that they get as attentive listening, shared decision making, and understanding the patient behind the disease. This is supported by a study by Marshal et al32 where patients wanted their care from the health care providers equated as connected and attentive. In another study, patients wanted provider behaviors that encouraged a helpful clinical relationship that explains procedures step-by-step and is attentive to body language.33 This finding is supported by another similar study, which describes that health care providers have a duty focusing on patients rather than doing their jobs without patient-focused care.34 This is closely related to the point that health care providers should provide the utmost person-centered care to their patients.35

Patients conceived that information was an aspect of patients’ rights. Patients want to participate in their treatment and take part in decision making. They considered it important that health care providers invited them to participate, to give them advice, and did not withhold information. In their opinion, decisions should be taken in an atmosphere of mutual understanding, thus enabling them to influence their situation and care. Previous studies reported that patients were motivated to be involved and value their participation.36,37 But, another study showed that patients only partly participated in their care and were not actually invited to take part in decision making, due to the fact that health care providers believed that patients did not have enough knowledge, as well as wishing to have control over the patient.38 It is, therefore, essential for health care providers to change such attitudes in involving patients in care and support them to be empowered. Health care providers who use a language that patients do not understand create a barrier to the patient’s participation. A shared dialog between the patient and the health care provider creates a commitment that they can discuss to each other for shared decision making. It is also important to create trust between the patient and the health care provider.39

In this study, patients reiterated that they have to feel secured in the processes of health care delivery services. They claim control over their privacy not to expose them to the vision of others during consultation or physical examination. Other studies also support this that patients needed a private atmosphere during treatment.40 Doyle and Bagaric41 argued that there is a need to reassess the desirability of introducing a separate cause of action protecting privacy interests in health care.

This study also reveals that keeping secrets related to the disease was an important conception related to patients’ rights practice. This is also related to patients’ conception of keeping patient information secret. Health care providers have the responsibility of keeping information confidential about professional relationship with the patients and the disease affecting them. Patients needed their consultation and care in a private room so as to minimize information leakage. This indicates that health care providers have responsibility of respecting their privacy and confidentiality to feel them secured. This is supported by other similar studies as every patient has the right to control over information about them and right to privacy.42,43 Another study also shows that patients’ expectation from the health care provider should be comprehensive and performed with respect to ethical principles,44 but a qualitative study by Woogara45 on patients’ privacy showed that patients had little privacy in the wards.

Respect patients’ dignity was among the categories of patient rights. Patients aspired to be seen as valuable and treated as human beings. They need respect and attentive care regardless of disease status, ethnicity, residence, occupation, income status, or sex. This is also related to the need to preserve independent identity as they want to be seen as the person they were before having the capacity to work and being healthy. This is related to a study report on patients’ expectation in dignity, that is, respecting patient’s dignity will prompt attention, treat patients as equals, feel secured, and make the patient comfortable.46 Similarly, other studies show that illness47 or hospitalization43 hampered patients’ dignity, and most importantly, privacy of the person and dignity are interrelated.10

Patients anticipated being seen by an experienced health care provider. But this can only be possible if patients have obtained a direct referral to the reputable health care provider in the hospital. Patients also needed a referral to other hospital(s) if they experienced a shortage of diagnostic materials and drugs in the hospital, or to search for a better skilled health care provider.

This study has some limitations. The participants were patients in the adult general, medical, or surgical outpatient departments or patients of medical or surgical wards in an inpatient. Patients in other clinical departments were not included in the study. The identified categories, however, might still be transferable to similar contexts.

Conclusion and recommendations

Rights flow from outlooks in a social context28 and everything that encompasses is considered as patients’ rights.18 Therefore, the results showed that patients’ conceptions of patients’ rights practice in the hospital context are categorized differently. By recognizing patient rights as patient-centered practice, being secured, respecting their dignity, and getting referral, practicing patient rights could influence the patient’s experiences and satisfaction in relation to their hospital stay. Any health care can be characterized by considering patient rights. It is important that health care providers should acknowledge patient rights in the health care continuum. Health care ethics training in both pre-service and in-service overall, as well as ethical reasons in daily activities, should get due attention. Policy makers should take responsibility in drafting patients’ bill of rights in the Ethiopian context, and health care providers and managers should take part in identifying situations that violate patients’ rights. Future research on the patients’ rights practice from the health care provider’s perspective should also be conducted to examine how health care providers see their experience.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all individuals who participated in this study. Furthermore, we thank Doctor Mirgissa Kaba and Doctor Wubgizare Mekonnen for their valuable comments. We also express our thanks to Addis Ababa University for financing this study.

Author contributions

AB contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, and writing of the article. FE contributed to the design and analysis and critically revised the article. Both authors read and approved the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

WHO Resource book on mental health, human rights and legislation. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. | |

Pinch WJE, Kowanko I. Confidentiality: concept analysis and clinical application. Nurs Forum. 2000;35(2):5–16. | |

United Nations [webpage on the Internet]. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available from: http://www.Unhchr.ch/chrono.htm. Accessed April 19, 2013. | |

United Nations [webpage on the Internet]. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 1966. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2014. | |

World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]. Declaration of Alma Ata “Health for All”. World Health Organization; 1978. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/113877/E93944.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2014. | |

World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]. The Ottawa Charter of Health Promotion. World Health Organization; 1986. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/. Accessed May 1, 2014. | |

Europe Co [webpage on the Internet]. Declaration of the Committee of Ministers on Human Rights and the Rule of Law in the Information Society. 2005. Available from: https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=849061. Accessed April 24, 2014. | |

United Nations [webpage on the Internet]. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nation; 1948. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/. Accessed April 11, 2014. | |

Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K. Maternal satisfaction on delivery service and its associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public health facilities of Debre Markos town, Northwest Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:460767. | |

Woogara J. Patients’ privacy of the person and human rights. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(3):273–287. | |

World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]. A Declaration on The Promotion of Patients’ Rights in Europe. World Health Organization; 1994. Available from: http://www.who.int/genomics/public/eu_declaration1994.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2014. | |

Yousuf R, Fauzi A, How S, Akter S, Shah A. Hospitalised patients’ awareness of their rights: a cross-sectional survey from a tertiary care hospital on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Singapore Med J. 2009;50(5):494–499. | |

World Health Assembly [webpage on the Internet]. International Digest of Health Legislation. World Health Organization; 1949. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/86065#sthash.H5a91aB7.dpuf. Accessed May 29, 2015. | |

Dew K, Roordal M. Institutional innovation and the handling of health complaints in New Zealand: an assessment. Health Policy. 2001;57(1):27–44. | |

Nasiripour AA, Mahmoudi G, Raeissi P. A survey on exploring the dimensions of access to medical services. World Appl Sci J. 2011;13(3):424–430. | |

Nasiripour AA, Siadati SA, Maleki MR, Nasrabadi AN. Towards a comprehensive model of patient empowerment through nursing strategies: a study in Iranian hospitals. World Appl Sci J. 2011;14(3):408–413. | |

Taghizadeh F, Monfared SJ. The client satisfaction of health care in public and private centers and health houses in Qom province. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2011;7(6):1019–1023. | |

Joolaee S, Hajibabaee F. Patient rights in Iran: a review article. Nurs Ethics. 2012;19(1):45–57. | |

Barofsky I. Patients’ rights, quality of life, and health care system performance. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(5):473–484. | |

Almoajel AM. Hospitalized patients awareness of their rights in Saudi governmental hospital. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2012;11(3):329–335. | |

Tengilimoglu D, Kisa A, Dziegielewski S. What patients know about their rights in Turkey. J Health Soc Policy. 2000;12(1):53–69. | |

Constitution of The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Federal Negarit Gazeta. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Berhanena Selam Printing Enterprise: 1995. | |

Transitional Government of Ethiopia. National Policy on Health. Addis Ababa: Transitional Government of Ethiopia, 1993. | |

Federal Ministry of Health [homepage on the Internet]. Health Sector Transformation Plan of Ethiopia (2015/16-2019/20). FMOH; 2015. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.et. Accessed February 25, 2016. | |

Central Statistical Agency [homepage on the Internet]. (2014). Available from: http://www.csa.gov.et. Accessed June 12, 2014. | |

Marton F. Phenomenography – describing conceptions of the world around us. Instr Sci. 1981;10:177–200. | |

Barnard A, McCosker H, Gerber R. Phenomenography: a qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(2):212–226. | |

Marton F, Booth S. Learning and Awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1997. | |

Sjöström B, Dahlgren LO. Applying phenomenography in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(3):339–345. | |

Tschudin V. Ethics in Nursing: The Caring Relationship. Third ed. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2000. | |

Joolaee S, Hajibabaee F. Patient rights in Iran: A review article. Nursing Ethics. 2012;19(1):45–57. | |

Marshall A, Kitson A, Zeitz K. Patients’ views of patient-centred care: a phenomenological case study in one surgical unit. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(12):2664–2673. | |

Raja S, Hasnain M, Vadakumchery T, Hamad J, Shah R, Hoersch M. Identifying elements of patient-centered care in underserved populations: a qualitative study of patient perspectives. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126708. | |

Joolaee S, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi A, Parsa-Yekta Z, Tschudin V, Mansouri I. An Iranian perspective on patients’ rights. Nurs Ethics. 2006;13(5):488–502. | |

Grøndahl VA, Wilde-Larsson B, Karlsson I, Hall-Lord ML. Patients’ experiences of care quality and satisfaction during hospital stay: a qualitative study. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2012;1(1):185–192. | |

Tobiano G, Bucknall T, Marshall A, Guinane J, Chaboyer W. Patients’ perceptions of participation in nursing care on medical wards. Scand J Caring Sci. Epub 2015 Feb 19. | |

Tobiano G, Marshall A, Bucknall T, Chaboyer W. Patient participation in nursing care on medical wards: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(6):1107–1120. | |

Henderson S. Power imbalance between nurses and patients: a potential inhibitor of partnership care. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(4):537–545. | |

Frank C, Asp M, Dahlberg K. Patient participation in emergency care – a phenomenographic study based on patients’ lived experience. Int Emerg Nurs. 2009;17(1):15–22. | |

Hutton A. Consumer perspectives in adolescent ward design. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(5):537–545. | |

Doyle C, Bagaric M. The right to privacy: appealing, but flawed. Int J Hum Rights. 2005;9(1):3–36. | |

Widang I, Fridlund B, Martensson J. Women patients conception of integrity within health care: a phenomenographic study. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(5):540–545. | |

Kalyani MN, Kashkooli RI, Molazem Z, Jamshidi N. Qualitative inquiry into the patients’ expectations regarding nurses and nursing care. Adv Nurs. 2014;2014:6. Article ID 647653. | |

Matiti MR, Trorey GM. Patients’ expectations of the maintenance of their dignity. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(20):2709–2717. | |

Woogara J. Patients’ privacy of the person and human rights. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(3). | |

Whitehead L. Toward a trajectory of identity reconstruction in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a longitudinal qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;37(8):1023–1031. | |

Warren J, Holloway I, Smith P. Fitting in maintaining a sense of self during hospitalization. Int J Nurs Stud. 2000;37(8):229–235. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.