Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 14

The Era of Coronavirus: Knowledge, Attitude, Practices, and Barriers to Hand Hygiene Among Makerere University Students and Katanga Community Residents

Authors Nuwagaba J , Rutayisire M, Balizzakiwa T, Kisengula I, Nagaddya EJ, Dave DA

Received 12 May 2021

Accepted for publication 3 August 2021

Published 14 August 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 3349—3356

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S318482

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Julius Nuwagaba,1,2 Meddy Rutayisire,1,2 Thomas Balizzakiwa,1,2 Ibrahim Kisengula,1,2 Edna Joyce Nagaddya,1,2 Darshit Ashok Dave1,2

1Department of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; 2Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala, Uganda

Correspondence: Julius Nuwagaba; Dave Darshit Ashok

Department of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, P.O.Box 7072, Kampala, Uganda

Tel +256782774038

; +256752443624

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: The Novel Coronavirus was declared as a pandemic by the WHO at the end of 2019. Proper hand hygiene was identified as one of the simplest most cost-effective Covid-19 control and prevention measures. It is therefore very important to identify gaps in the knowledge, attitude, and practices, and barriers regarding hand hygiene in the community.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using a simple random sampling technique. An interviewer-guided questionnaire with questions on knowledge, attitude, practice, and barriers to hand hygiene was used in data collection. Collected data were analyzed using Microsoft office excel 2016 and STATA 15 software. A 95% confidence interval was used and statistical significance was P< 0.05.

Results: Only 88 (24.5%) of the participants had adequate knowledge of hand hygiene. 32.8% of the university students had adequate knowledge compared to 6.3% of the Katanga residents. The majority of 336 (93.6%) participants had a good attitude towards hand hygiene. University students had a significantly better knowledge of hand hygiene while Katanga slum residents had a slightly better attitude towards hand hygiene. Only 19.6% accomplished all the seven steps of handwashing. 38.4% of the participants were still greeting by handshaking. Of the participants, 60.1% noted lack of soap as a barrier to hand hygiene and 62.9% reported having more than three barriers to hand hygiene. Participants who had been taught handwashing were more likely to have better hand hygiene knowledge and practice.

Conclusion: There was an overall high proportion of participants with a low level of hand hygiene knowledge. There is a need for optimizing hand-hygiene practices through addressing the barriers and promoting public health education.

Keywords: Covid-19, knowledge, attitude, practice, barriers, hand hygiene, undergraduates, Katanga community

Introduction

Coronaviruses are a large family of zoonotic viruses that cause illness that ranges from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV).1,2 The novel coronavirus (nCoV) is a new strain that had not been previously identified in humans until the end of 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei province, China.3,4 The 2019-nCoV can transmit among humans5,6 and as of 29th May 2020, there were 5,701,337 cases and 357,688 deaths globally.7 Among other forms of spread, a person can get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their mouth, nose, or possibly their eyes.8,9

Handwashing with soap can reduce the risk of acute respiratory infections by 16% to 23%.10 WHO and the Uganda Ministry of Health recommend hand hygiene as one of the essential means to prevent the spread of all infections and in particular COVID 19. Other measures recommended include maintaining social distance, avoiding crowds, practicing respiratory hygiene, avoiding touching eyes, nose, and mouth, keeping up to date on the latest information from trusted sources, self-quarantine, cleaning frequently touched surfaces, and seeking medical care in case of symptoms.11,12 The promotion of safe hygiene is the single most cost-effective means of preventing infectious disease.13 During a global pandemic, one of the cheapest, easiest, and most important ways to prevent the spread of a virus is to wash your hands frequently with soap and water.14–16

The promotion of hand hygiene behavior remains a complex issue.17,18 Reasons for non-compliance with recommendations occur at individual, group, and institutional levels.19 Individual factors such as social cognitive and psychological determinants (ie, knowledge, attitude, intentions, beliefs, and perceptions) provide additional insight into hand hygiene behavior.20 Perceived barriers to adherence to hand hygiene practice recommendations include inaccessible hand hygiene supplies, forgetfulness, lack of knowledge of guidelines, insufficient time for hand hygiene.21 Despite considerable efforts, compliance with hand hygiene as a simple infection-control measure remains low22 and hygiene is suboptimal in both community and healthcare settings in African countries.23

Several studies have compared different hand hygiene methods in hospital settings.21 In contrast, few studies have been published on the effect of hand hygiene on bacterial contamination of hands in the community.24,25 Makerere University, the largest university in Uganda is one of the high-risk areas of COVID-19 transmission due to factors like a large student and staff community.26 The university is surrounded by several communities including Katanga slum which is located between the main campus and the Medical school. These are high concentration areas with a high risk of community transmission of COVID 19. This research served to identify gaps in the knowledge, attitude, and practices and barriers regarding hand-hygiene among the Makerere University students and Katanga slum residents. The results from this study are very useful in paving a way for comprehensive intervention for successful behavior change programs on measures for the implementation of proper hand hygiene.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Site, and Population

We employed a descriptive cross-sectional study design among the Makerere University medical students and non-medical students residing in halls of residence. Data was also collected from the residents of Katanga slum, a settlement located in the valley between Mulago Hospital and Makerere University and its map can be accessed on https://goo.gl/maps/fqMmkk6cR1k4pNVbA. The study included only undergraduate students and Katanga slum residents aged 18 years and above who were able to understand English or Luganda languages.

Sample Size Estimation

Makerere University was estimated to have 3000 undergraduate students, while 5000 students were estimated to reside in Makerere University halls of residence, and, Katanga residents were estimated at 7000 people. The total estimate was therefore 15,000. Using Yamane’s formula (1967): n=N/ (1+Ne^2). N being the population size of 15,000. “e” being the precision level as 5%. “n” being the sample size, which was calculated as 390 participants.

Data Collection

Data were collected from 17th to 22 March 2020 using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire for all participants. Based on the literature review in the background, the authors drafted a questionnaire to address the knowledge, attitude, and aspects of practices and barriers to hand hygiene concerning the COVID 19 pandemic. The original English questionnaire was translated into Luganda, the local language spoken by residents of the Katanga community. Before using the tool, the Luganda tool was translated back to English to check for consistency. Data were collected on sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, and practice of hand hygiene, and barriers to proper hand hygiene. The participants were recruited by simple random sampling technique and they were interviewed from their places of residence, work as well as from their respective colleges for the students.

Data Management and Analysis

The collected data was entered using epicollect5 software. This was after a thorough check for completion. The data were exported and analyzed using Microsoft office excel 2016 and STATA 15 software. Frequency distribution and percentages were used to display data in univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analysis. Nine parameters were used to assess the knowledge of patients on hand hygiene. Participants who got below 5 correct answers were taken to have inadequate knowledge while those who scored ≥5 were taken to have adequate hand hygiene knowledge. To measure attitude to hand hygiene, a 5-point Likert scale was used: strongly agree scored 5, Agree scored 4, Neutral scored 3, Disagree scored 2, and strongly disagree scored 1. Four parameters were used to assess the attitude towards hand hygiene (total score of 20). To analyze attitude, participants who scored 50% (≥10) were taken to have a good attitude, while those who scored ˂ 10 were taken to have a poor attitude towards hand hygiene. The practice of participants on hand hygiene was assessed based on how they greet in the era of COVID 19 and their ability to demonstrate the 7 steps of handwashing. The barriers of participants to hand hygiene were assessed on 6 parameters.

Association between participants’ knowledge, attitude, practice, and barriers was represented in an odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval using multivariate analysis. For all tests conducted in this study, a statistically significant level was accepted at p < 0.05. Spearman’s coefficient correlation was used to assess the relationship between knowledge and attitude to hand hygiene.

Ethical Approval

This study complies with the declaration of Helsinki on research involving human subjects.27 Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Mulago Hospital Research and Ethics Committee, approval number MHREC 1856. The approval to conduct the study within Katanga Slum was obtained from the Chairpersons of both Busia and Kimwanyi Zones. The enrolment of participants into the study was solely voluntary and only after written informed consent was sought from the participant. The participants were however free to withdraw from the study at any time point. Identification numbers instead of names of the respondents were used during the research and the data collected were treated with the utmost confidentiality.

Patient and Public Involvement

Participants and the public were not involved in the described study design or recruitment. However, the results were disseminated through the chairpersons, and will also be available as abstracts and manuscripts to the College of Health Sciences Makerere University, and open publication in this journal.

Results

Social Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

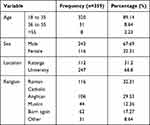

In this study, 359 people participated, of these, the majority (320) 89.14% were between 18 and 35 years. Of the participants, 243 (67.69%) were male while 116 (32.31%) were female. Katanga residents were 112 (31.2%) of the respondents while 247 (68.8%) were Makerere University students (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics |

Knowledge

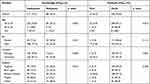

Overall, only 24.5% of the participants had adequate knowledge of hand hygiene. The majority of these 87 (98.9%) were young adults (18 to 35 years). Among university students, 32.8% had adequate knowledge compared to 6.3% of the Katanga residents (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, University students were 5.6 times (OR: 5.6, 95% C1: (2.3–13.9), P < 0.001) more likely to have adequate hand hygiene knowledge than Katanga residents, while the female participants were 1.8 times (OR: 1.8, 95%C1: (1.1–3.2)) more likely to have more knowledge than males P=0.031 as shown in Table 3. The religion and age of participants did not significantly affect the level of knowledge on hand hygiene.

|

Table 2 Knowledge and Attitude of Participants to Hand Hygiene |

|

Table 3 Multivariate Analysis of Knowledge and Attitude of Participants |

The study further showed that 227 (63.2%) of the participants had received prior teaching on hand hygiene. The highest percentage of those trained, 48% had received this training more than 3 months ago. More university students 177 (71.7%) had ever received teaching on hand hygiene compared to Katanga community residents 50 (44.6%). Of those with teaching on hand hygiene, 31.7% had adequate hand hygiene knowledge compared to only 12.1% of those that had no training on hand hygiene.

Acquiring teaching on hand hygiene increased knowledge by 3.4 times (OR: 3.4, 95% CI: (1.9–6.1), P < 0.001). University students were 3.1 times (OR: 3.1, 95% C1: (2.0–5.0), P < 0.001) more likely to have had a teaching on hand hygiene than Katanga residents.

Social media was the most common source of information about hand hygiene as a preventative measure for COVID 19 followed by television, 38.7%, and 28.1%, respectively. The commonest source of information among Katanga residents was television (51.8%) followed by radio (25.9%) while among university students, the commonest source of information was social media (52.6%). However, the source of information did not affect the level of knowledge of hand hygiene.

Attitude

Overall 93.6% of the participants had a good attitude to hand hygiene. All the social demographic characteristics did not significantly affect the attitude of the participants towards hand hygiene (Table 2). Although bivariate analysis showed that participants that had been taught hand hygiene prior were 2.4 times (OR: 2.4, 95% C1: (1.0–5.6), P=0.048) more likely to have a good attitude to hand hygiene, there was a poor positive relationship between knowledge of the participants and their attitude to hand hygiene due to a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.0734.

Practice

Participants that were still greeting by handshaking were 138 (38.4%) while 149 (41.5%) of the participants greeted with only facial expressions. Only 70 (19.6%) were able to demonstrate all the seven steps of handwashing while 144 (40.2%) demonstrated less than three handwashing steps. Of the Katanga slum resident 1 (0.9%), 32 (28.6%) and 79 (70.5%) demonstrated all seven, three to six and ≤ two handwashing steps unlike 69 (28.0%), 112 (45.5%) and 65 (26.4%) of Makerere University students, respectively (p-value <0.001). Knowledge and attitude of participants on hand hygiene did not affect the way they were greeting in the era of COVID 19 at the time of the study. Participants who demonstrated all the seven steps of handwashing were 9.2 times (OR: 9.2, 95%C1: (4.3–20.0), P < 0.001) likely to have been taught handwashing than those who demonstrated less than three steps or demonstrated handwashing without soap use of soap. This had a Spearman correlation 0.3630 showing a fair positive relationship.

Barriers

Based on multiple responses from each participant, the biggest barrier to hand hygiene was lack of soap, detergents, alcohol-based hand rub, or antiseptic, reported by 211 (60.1%) of the participants. The most common barrier among university students was lack of soap and/or antiseptics, 66.4% while negligence was the most common barrier in Katanga residents, 59.6%. The largest percentage of the participants 62.9% reported having more than three barriers to hand hygiene (Table 4). University students were 5.3 times (OR: 5.3, 95%C1: (1.6–17.6), P=0.006) more likely to have many barriers to hand hygiene than Katanga residents.

|

Table 4 Barriers to Proper Hand Hygiene |

Discussion

COVID 19 is a global pandemic with a high transmission rate.28 One of the best measures to address the transmission of COVID 19 is adherence to proper hand hygiene practice.14 It is therefore important to understand the knowledge, attitude, and practice of high-risk areas to hand hygiene. Together with establishing the existing barrier to hand hygiene, solutions can be formulated on proper infection prevention to limit the spread of COVID 19 in the communities.

Overall, only 24.5% of the participants had adequate knowledge of hand hygiene, a finding that is similar to a study among medical students in India and at Kampala International University Uganda.29,30 Of the participants, 63% had ever received teaching on hand hygiene, leaving 37% of the participants without prior teaching on hand hygiene. More university students, 71.7% and received teaching on hand hygiene as compared to 44.6% of Katanga community residents. This explains the finding where more university students, 32.8% had adequate knowledge compared to only 6.3% of the Katanga residents who had adequate hand hygiene knowledge. There is therefore a need for health education on hand hygiene to address this gap. Among those with teaching on hand hygiene, 31.7% had adequate knowledge compared to 12.1% of those that had no training on hand hygiene who had good hand hygiene knowledge. A finding that further expresses the importance of hand hygiene education in public health response. This knowledge was not affected by who delivered the teaching and/or when it was delivered. This concluded that any person with hand hygiene knowledge, is positioned to deliver information to another individual and this should be promoted. The commonest sources of information on hand hygiene as a control measure for the spread of COVID 19 were Social media (38.7%), Television (28.1%), radio (11.4%), etc., in descending order. This shows the importance of these forms of communication in connecting with communities31,32 and this should be used to promote hand hygiene in this pandemic.

The study also found that 93.6% of the participants had a good attitude towards hand hygiene which is similar to a study among Kampala International University medical students who were found to have a positive attitude towards hand hygiene.30 A poor positive relationship between hand hygiene knowledge and attitude calls for further research to identify the factors that influence the attitudes of populations to hand hygiene. Similar to a study among Chinese adults,33 the location of participants was found to be an important associated factor to influence their knowledge and attitude towards hand hygiene, with Katanga residents having a lower level of knowledge but a more positive attitude and better hand-hygiene practices than the university students. Amidst the growing worldwide incidence and the fact that Uganda had already registered the index case of COVID 19.34 Our study established that 38.4% of the participants were still greeting by handshaking and/or hugging. This showed a poor hand hygiene practice among these participants and subsequent high risk of community transmission of COVID 19. Only 19.6% of the participants were able to demonstrate the 7 steps of handwashing. Participants who had been taught hand hygiene were 9.2 times more likely to demonstrate all the seven steps than their counterparts, further showing the importance of hand hygiene education and promotion as a means of improving its proper practice.21

The commonest barriers to hand hygiene were lack of soaps, antiseptics, detergents and alcohol sanitizers, lack of running water, and negligence findings that are no different from a study by Muiru30 and a study by Al-Naggar which showed that laziness was the main barrier.35 The majority of the patients had more than three barriers to hand hygiene. This is a very big public health problem that limits proper hand hygiene and which is the single most effective protective measure against COVID 19,11–13 and it needs to be addressed.

Conclusion

There was an overall high proportion of participants with a low level of knowledge. The location of the participants was found to be an important associated factor to the level of knowledge and attitude to handwashing, with Katanga residents having a lower level of knowledge but a more positive attitude and better hand-hygiene practices than the university students. To reduce the spread of COVID 19 infections and stop the pandemic, there is a need for optimizing hand-hygiene practices through addressing the barriers and promoting public health education.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author, Nuwagaba Julius on a reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to residents of Katanga Slum and students of Makerere University for participating in the study. We acknowledge the following people; Kenneth Kato Agaba, Julius Musisi, Kevin Adongo, Laurita Nakyagaba, Patricia Mwachan, Abraham Byomugabe, Mavol Tukwataniise, Ivan Ongebo, and John Muhenda, for participating in data collection. We thank Prof. Sarah Kiguli and Dr. Margrete Lubwama for supervising us in the study, Dr. Bernard Kikaire, and Ronald Olum for their guidance in analysis and manuscript writing. This paper has also been submitted as a preprint to medRxiv.

Funding

The study was funded by the authors with help from Dr. Margaret Lubwama who contributed to the printing of study questionnaires.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

1. Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69(4):635–664.

2. Su S, Wong G, Shi W, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490–502.

3. Coronavirus disease: what you need to know. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/coronavirus-disease-what-you-need-know.

4. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733.

5. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207.

6. Phan LT, Nguyen TV, Luong QC, et al. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):872–874.

7. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 130. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200529-covid-19-sitrep-130.pdf?sfvrsn=bf7e7f0c_4.

8. CDC. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). How COVID-19 spreads. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprepare%2Ftransmission.html.

9. WHO. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations.

10. Rabie T, Curtis V. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: a quantitative systematic review. Trop Med Int Heal. 2006;11(3):258–267.

11. WHO. Clean care is safer care, clean hands protect against infection. Available from: https://www.who.int/gpsc/clean_hands_protection/en/.

12. Case-management-guidelines_final-version-soft-copy, national guidelines for management of COVID-19. Available from: https://www.health.go.ug/covid/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19_Case-Management-Guidelines_Final-Version-soft-copy_23April-2020.pdf.

13. Curtis V, Schmidt W, Luby S, Florez R, Touré O, Biran A. Hygiene: new hopes, new horizons. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(4):312–321.

14. UNICEF. Everything you need to know about washing your hands to protect against coronavirus (COVID-19). Washing your hands can protect you and your loved ones. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/everything-you-need-know-about-washing-your-hands-protect-against-coronavirus-covid-19.

15. Ejemot‐Nwadiaro RI, Ehiri JE, Arikpo D, Meremikwu MM, Critchley JA. Hand washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004265

16. Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(5):275–281. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6.

17. Stone S, Teare L, Cookson B. Guiding hands of our teachers. Hand-hygiene Liaison Group. Lancet. 2001;357(9254):479–480.

18. Pittet D. Improving compliance with hand hygiene in hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(6):381–386.

19. Pittet D. Compliance with hand disinfection and its impact on hospital-acquired infections. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48(Suppl A):S40–6.

20. Kretzer EK, Larson EL. Behavioral interventions to improve infection control practices. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26(3):245–253.

21. WHO. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland; 2009. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf.

22. Hugonnet S, Pittet D. Hand hygiene revisited: lessons from the past and present. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000;2(6):484–489. doi:10.1007/s11908-000-0048-2.

23. Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Hygiene behaviour and health attitudes in African countries. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):149–154.

24. World Health Organization. Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/launch-version-report-jmp-water-sanitation-hygiene.pdf.

25. Wolf J, Johnston R, Freeman MC, et al. Handwashing with soap after potential faecal contact: global, regional and country estimates. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(4):1204–1218.

26. VC Statement on the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic. The College of Engineering, Design, Art and TechnologyMakerere University. Available from: https://cedat.mak.ac.ug/news/vc-statement-on-the-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-epidemic/.

27. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki, Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects; 2008.

28. McKibbin WJ, Fernando R. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. 2020.

29. Nair SS, Hanumantappa R, Hiremath SG, Siraj MA, Raghunath P. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of hand hygiene among medical and nursing students at a Tertiary Health Care Centre in Raichur, India. ISRN Prev Med. 2014;2014:608927.

30. Muiru HW. Knowledge, attitude and barriers to hands hygiene practice: a study of Kampala International University undergraduate medical students. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2018;5(9):3782–3787.

31. Howard A. Connecting with Communities: How Local Government is Using Social Media to Engage with Citizens. 2012.

32. Atkin CK, Wallack L. Mass Communication and Public Health: Complexities and Conflicts. Vol. 121. Sage; 1990.

33. Tao SY, Cheng YL, Lu Y, Hu YH, Chen DF. Handwashing behaviour among Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study in five provinces. Public Health. 2013;127(7):620–628.

34. Uganda confirms first coronavirus case. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Uganda-registers-first-Coronavirus-case/688334-5499930-13fqak2z/index.html.

35. Al-Naggar RA, Al-Jashamy K. Perceptions and barriers of hands hygiene practice among medical science students in a medical school in Malaysia. Int Med J Malaysia. 2013;12:2.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.