Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

The Effect of Social Perspective-Taking on Interpersonal Trust Under the Cooperative and Competitive Contexts: The Mediating Role of Benevolence

Authors Sun B , Yu X, Yuan X, Sun C, Li W

Received 11 March 2021

Accepted for publication 31 May 2021

Published 21 June 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 817—826

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S310557

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Binghai Sun, Xiajun Yu, Xuhui Yuan, Changkang Sun, Weijian Li

School of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xuhui Yuan; Changkang Sun

School of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, 688 Yingbin Avenue, Jinhua, 321004, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 1 803 745 9323; +86 1 351 692 8402

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: Several studies have demonstrated that perspective-taking can foster interpersonal trust. However, few studies have explored the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust under a specific social context and its internal mechanism. The present study explored the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust and further examined this interaction under two different social contexts: a cooperative vs a competitive context. We also explored why social perspective-taking fostered interpersonal trust.

Methods: Study 1 (N = 45) was conducted using a within-subjects design in which participants were asked to read the dilemmas of two partners under two conditions (social perspective-taking vs objective focus) and complete the trust game after each reading. In Study 2 (N = 135), we manipulated the social context by a word memorization task to explore the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust under different contexts (competitive vs cooperative). In Study 3, we examined benevolence as a mediator in the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust.

Results: Study 1 showed that interpersonal trust under the social perspective-taking condition was significantly higher than interpersonal trust under the objective focus condition. Study 2 showed that under the cooperative context, participants under the social perspective-taking condition invested more money to another partner than those under the objective focus condition. However, under the competitive context, the results were the opposite. Study 3 demonstrated that benevolence mediated the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust in both cooperative and competitive contexts.

Conclusion: Social perspective-taking could improve interpersonal trust under a cooperative context, while the degree of interpersonal trust decreases under a competitive context. Moreover, social perspective-taking could influence the perception of benevolence and thereby enhance or diminish interpersonal trust.

Keywords: interpersonal trust, social perspective-taking, benevolence, cooperation, competition

Introduction

Interpersonal trust is a pervasive phenomenon defined as the “willingness to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of another’s behavior,”1 and is an indispensable part of social communication and at the core of relationship management. It is an important form of social capital, which can promote or damage economic, social, and other forms of communication.2 There is ample evidence demonstrating that trust is essential for both individual and national well-being.3,4 Based on its importance, it is necessary to explore factors that affect interpersonal trust.

Several studies have shown that interpersonal trust may be affected by perspective-taking. These studies show that individuals with high social perspective-taking ability pay more attention to others5,6 and invest more in another stranger.7,8 Individuals with high social perspective-taking ability were better at looking at problems from the perspective of others and were more likely to trust others.9 However, experimental evidence for a causal relationship between the two constructs is lacking. Furthermore, perspective-taking can be divided into spatial and social perspective-taking.10 Spatial perspective-taking is an ability to mentally adapt; it represents the spatial relationship from another person’s viewpoint.11 Social perspective-taking is the psychological process of contemplating and inferring the perspective of others.12 Erle13 found that spatial perspective-taking fostered interpersonal trust by using a novel visuo-spatial manipulation of perspective-taking. However, visuo-spatial manipulation involves the inference of others’ spatial perspectives but does not involve the inference of others’ attitudes and emotions. Thus, the present study explored the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust; specifically. We hypothesized that social perspective-taking would increase interpersonal trust (H1).

Another related area of research investigation concerns whether social perspective-taking has the same effect on interpersonal trust in different interpersonal contexts. Cooperation and competition are part of our daily lives.14 Previous studies have found that prosocial behavior decreased and selfish behavior increased after perspective-taking under the competitive context, and not the cooperative context.15–17 Trend analyses revealed that as trust increased, overall prosocial behavior increased.18 Moreover, theoretical notions concerning the reliability of the source of an intention indicated that a cooperative orientation leads individuals to feel that the welfare of the partner as well as his own welfare, and then would lead to trusting and trustworthy behavior. Whereas a competitive orientation would lead to suspicious and untrustworthy behavior.19 Social perspective-taking as a psychological process of contemplating and inferring the perspective of others may further enhance the perception of trustworthiness of cooperative or competitive partners. Given the findings of prior studies, the present study explored the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust under different contexts; specifically, we hypothesized that interpersonal trust would increase after social perspective-taking under the cooperative context, and decrease under the competitive context (H2).

Some studies indicate that benevolence might play a crucial role in the relationship between perspective-taking and interpersonal trust. Benevolence refers to the extent to which a trustee is believed to want to do good to the trustor, aside from an egocentric profit motive.20 Social perspective-taking could affect the benevolence judgment toward another.21 Mayer et al20 proposed a model of trust in 1995 in which integrity, benevolence, and ability are considered important characteristics of the trustee. Compared to integrity and ability, benevolence is a key ingredient in the generation of interpersonal trust.22,23 The perception of benevolence can directly affect the trustor’s trust in the trustee. The higher the perceived benevolence, the more trust the trustor has in the trustee.20,22,24 Under the cooperative context, the cooperative motivational orientation would lead the individual to expect the other person to have a benevolent intention toward them.19 Social perspective-taking could increase the perception of others’ benevolence, thereby, leading to the prediction of trusting and trustworthy behavior from the partner. Under the competitive context, the individual with the competitive orientation would expect a reliably malevolent intention from the partner.19 Thus, social perspective-taking could increase the perception of others’ non-benevolent intentions, and lead the individual to predict suspicious and untrustworthy behavior from the partner. Moreover, a series of experiments demonstrated that considering others’ perspectives activated reactive egoism (ie, egoistic or self-serving behavior in reaction to the presumably egoistic behavior of others) under a competitive context. When individuals perceived the psychological activities of competitors as having low benevolence, they responded with low benevolence performance.25 However, this reactive egoism was attenuated under cooperative contexts,15 resulting in increased prosocial behavior.16 In the present study, we hypothesized that the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust would be mediated by benevolence (H3). It was expected that under the competitive context, social perspective-taking would diminish individuals’ perceived benevolence of the competitors, thereby decreasing interpersonal trust. Conversely, under the cooperative context, social perspective-taking would enhance individuals’ perceived benevolence of the partners, thus increasing interpersonal trust.

We conducted three studies to investigate the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust to test three hypotheses. In Study 1, we adopted a within-subjects design to test the hypothesis that social perspective-taking would increase interpersonal trust (H1). Study 2 was an experimental study to test the hypothesis that social perspective-taking would increase interpersonal trust under the cooperative context, and decrease interpersonal trust under the competitive context (H2). Study 3 was an experimental study to test the hypothesis that the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust would be mediated by benevolence (H3). Based on Study 2, we examined whether the mediated relationships differed under competitive vs cooperative contexts. Three studies were by the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Human Experiment Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University. All participants signed written informed consent. Participants were debriefed about the study purpose and were informed that they could withdraw from participation at any time and without any consequences.

Study 1

Study 1 investigated whether social perspective-taking enhances interpersonal trust in the first-time interaction with another individual. It was hypothesized that in the absence of other trust signals, social perspective-taking would increase interpersonal trust.

Participants and Design

Forty-five university students (24 women, M = 20.17 years, SD = 1.31) were recruited from the Zhejiang Normal University by advertising the study. Participants received ¥15 for their participation. A one-factor (viewing orientation: social perspective-taking vs objective focus) within-subjects design was used. The dependent variable was interpersonal trust from the trust game.

Procedure and Materials

Participants were instructed that they would continuously read about two partners’ stressful life dilemmas; one from a social perspective and one from an objective focus (for a similar manipulation, see Shih et al26). Under the social perspective-taking condition, participants were asked to place themselves in the role of the partner and imagine how they would feel during the dilemma. Under the objective focus condition, participants were asked to understand the cause of the dilemma as objectively as possible from the perspective of a bystander. To remove order effects, the order of the condition was randomly assigned.

Participants were asked to play a trust game with a partner after each reading. The trust game has been widely used to measure trust.27 In the present study, all participants were provided the following game rules:

Now, you have been endowed with ¥10. You can choose to send to the partner ¥n, 0 ≤ n ≤ 10. If you decide to send ¥n to ¥, then the partner will receive ¥3n. The partner can then choose to return ¥m to you after receiving ¥3n, 0 ≤ m ≤ 3n. For example, if you decide to send ¥3 to the partner, the partner will receive ¥9, and the partner can then choose to return any amount between ¥0 and ¥9 to you. Please indicate the amount (¥______) that you would send to the other partner.

After each trust game task, a manipulation check for social perspective-taking was administered. Participants were asked to answer a question:

When reading another partner’s text, from which viewpoint did you read it as much as possible? Did you put yourself in the other person’s perspective as much as possible, or stand as objectively as possible from the perspective of the observer?

Results

Manipulation Checks

In the manipulation check for social perspective-taking, if the participants under the social perspective-taking condition answered “stand as objectively as possible from the perspective of the observer,” or the participants under the objective focus condition answered “put yourself in the other person’s perspective as much as possible,” the participants were excluded from the analyses. Two participants were excluded using this criterion, resulting in 43 participants that were included in the analysis.

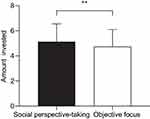

We performed a paired samples t-test to analyze the amount of money sent to another partner, which represents the level of interpersonal trust. The results showed that the amount of money sent under the social perspective-taking condition (M = 5.14, SD = 1.41) was significantly higher than the amount sent under the objective focus condition (M = 4.74, SD = 1.36), t(42) = 2.87, p < 0.01, d = 0.44 (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 The average amounts of money sent in the trust game in Study 1. **p < 0.01. |

Discussion

The results of Study 1 showed that social perspective-taking increased interpersonal trust, providing support for H1. Our results are consistent with the findings of a previous study.13 Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that selfish behavior significantly increased after perspective-taking under a competitive context.15 Whereas reactive egoism was attenuated and prosocial behavior increased under cooperative contexts.16 Therefore, we designed Study 2 to explore the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust under the contexts of competition and cooperation.

Study 2

In Study 2, we tested the hypothesis that social perspective-taking would increase interpersonal trust under a cooperative context, while social perspective-taking would decrease interpersonal trust under a competitive context.

Participants and Design

One hundred thirty-two university students (68 women, M = 20.27 years, SD = 1.83) were recruited from Zhejiang Normal University by advertising the study. Participants received ¥15 for their participation. A 2 (viewing orientation: social perspective-taking vs objective focus) × 2 (context: competitive vs cooperative) factorial between-subjects design was used. Similar to Study 1, interpersonal trust was measured by the amount of money the participant sent to another partner in the trust game.

Procedure and Materials

Participants were first asked to complete a word memorization task in which 10 different words were presented for 5 seconds. They were instructed to memorize the words as much as possible within the specified time and perform the memory assessment after 5 seconds.28 Participants in the competitive group were told that their scores would be compared with the scores of another participant. Participants with a higher number of correct words would receive additional rewards. Participants in the cooperative group were told to randomly match with another participant to form a group to complete the cooperative task together. The results of the two individuals would be combined as the group performance and compared with other groups. The group with the highest number of correct words would receive additional rewards.

After the word memorization task, participants in the social perspective-taking group were asked to write about how another partner would feel about competing or cooperating with them, as well as the strategies they used in the word memorization task. Participants in the objective focus group were asked to write an objective description of their surrounding environment.

After the interaction with another partner, the participant played a trust game with that partner, as in Study 1.

Results

We performed a 2×2 between-subjects ANOVA for the amount of money sent to the other partner. As Table 1 indicates, the main effect of social perspective-taking was not significant, F(1, 130) = 0.02, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.00, while the main effect of context was significant, F(1, 130) = 13.39, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10. Moreover, there was a significant interaction effect, F(1, 130) = 11.61, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.08 (Figure 2). Further simple effects analysis indicated that, under the cooperative context, participants in the social perspective-taking group invested more money to another partner (M = 5.94, SD = 1.56) than those under the objective focus condition (M = 5.09, SD = 1.47), F(1, 130) = 6.24, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.05. However, under the competitive context, participants in the social perspective-taking group sent less money to another partner (M = 4.24, SD =1.29) than those in the objective focus group (M = 5.03, SD = 1.19), F(1, 130) = 5.38, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04.

|

Table 1 The Sample Size of the Participants and the Amount of Money Invested by the Participants Under the Four Conditions of Study 2 |

|

Figure 2 The average amounts of money sent in the trust game in Study 2. *p < 0.05. |

Discussion

The results of Study 2 showed that under the context of competition, social perspective-taking reduced interpersonal trust, whereas, under the context of cooperation, social perspective-taking increased interpersonal trust. These results provide support for H2 and are consistent with a prior study in which, the prosocial behavior of individuals under the competitive context was significantly reduced after perspective-taking.15 However, prosocial behavior increased under a cooperative context.16 Given that some studies indicated that benevolence might play a crucial role in the relationship between perspective-taking and interpersonal trust, Study 3 investigated the mediating role of benevolence.

Study 3

In Study 3, we tested the hypothesis that benevolence would mediate the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust under both the competitive and the cooperative context.

Participants and Design

One hundred thirty-two university students (72 women, M = 20.52 years, SD = 1.89) were recruited from Zhejiang Normal University by advertising the study. Participants received ¥15 for their participation. Same as in Study 2, a 2 (viewing orientation: social perspective-taking vs objective focus) × 2 (context: competitive vs cooperative) factorial between-subjects design was used. Same as in Studies 1 and 2, interpersonal trust was measured by the number of money participants sent to another partner in the trust game.

Procedure and Materials

Participants completed the same tasks as in Study 2 in the same order. The only change was that after completing the social perspective-taking task, participants completed a Benevolence Scale to rate the benevolence of their partner. The Benevolence Scale comprised five items that were adopted from a previous study.29 Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree that the statement accurately describes them using 5-point scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The following is a sample item: “The other party wouldn’t do anything to hurt me.” The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) was α = 0.95.

Results

The Effect of Social Perspective-Taking on Interpersonal Trust Under the Context of Cooperation and Competition

We performed a 2×2 between-subjects ANOVA for the amount of money sent to another partner. As shown in Table 2, the main effect of social perspective-taking was not significant, F(1, 130) = 0.61, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.05, whereas the main effect of context was significant, F(1, 130) = 19.66, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13. Moreover, there was a significant interaction effect, F(1, 130) = 18.52, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13 (Figure 3). Further simple effects analysis found that, under the cooperative context, participants in the social perspective-taking group sent more money to another partner (M = 6.33, SD = 1.19) than those in the objective focus group (M = 5.15, SD = 1.96), F(1, 130) = 12.93, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.09. However, under the competitive context, participants in the social perspective-taking group sent less money to another partner (M = 4.30, SD = 0.98) than those in the objective focus group (M = 5.12, SD = 0.96), F(1, 130) = 6.20, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.05.

|

Table 2 The Sample Size of the Participants and the Amount of Money Invested by the Participants Under the Four Conditions of Study 3 |

|

Figure 3 The average amounts of money sent in the trust game in Study 3. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. |

The Mediating Effect of Benevolence Under the Competitive Context

Mediation analysis (the Hayes PROCESS v3.0 macro in SPSS v20.0) was used to examine the mediating role of benevolence. Model 4 with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and 5000 Bootstraps was chosen for the analysis.30 The mediating role of benevolence was tested by computing the total effect (c), direct effect (c’), and 95% CI of the indirect effect (a*b). The effects were considered significant if the 95% CI did not include zero in mediation analysis. Table 3 provides the results of the mediation analysis. Under the competitive context, social perspective-taking had a significant and negative effect on benevolence (B = −1.03**p < 0.01, 95% CI = [−1.70, −0.37]) and benevolence further had a significant effect on interpersonal trust (B = 0.20*p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.40]). Although social perspective-taking had a significant and negative direct effect on interpersonal trust (B = −0.62*p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−1.15, −.09]), it also had a significant and negative indirect effect on interpersonal trust through benevolence (B = −0.20, 95% CI = [−0.49, −0.01]). This model is depicted in Figure 4.

|

Table 3 Results of the Mediation Analysis of Benevolence in the Path from Social Perspective-Taking to Interpersonal Trust Under the Competitive Context |

The Mediating Effect of Benevolence Under the Cooperative Context

We conducted the same analysis that was done to test for mediation under the competitive context. Table 4 provides the results of the analysis. Under the cooperative context, social perspective-taking had a significant and positive effect on benevolence (B = 0.97 ***p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.57, 1.36]) and benevolence further had a significant positive effect on interpersonal trust (B = 0.58*p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.09, 1.06]). In addition, while social perspective had no significant direct effect on interpersonal trust (B = 0.62, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.28, 1.52]), it had a significant and positive indirect effect on interpersonal trust through benevolence (B = 0.56, 95% CI = [0.16, 1.11]). This model is depicted in Figure 5.

|

Table 4 Results of the Mediation Analysis of Benevolence in the Path from Social Perspective-Taking to Interpersonal Trust Under the Cooperative Context |

Discussion

The results of Study 3 showed that benevolence mediated the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust under both the cooperative context and the competitive context. These results provide support for H3. Further, the mediated relationships differed under competitive vs cooperative contexts: benevolence fully mediated the relationship under the cooperative context and was a partial mediator under the competitive context. The results are consistent with Mayer et al’s20 model of trust, in which the trustee’s ability, benevolence, and integrity will directly affect the degree to which an individual will have trust in another.22

General Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrated that individuals were more likely to trust others when primed with taking a social perspective, supporting our first hypothesis. The results are consistent with research on the effects of visuo-spatial perspective-taking on trust.13 The essential feature of social perspective-taking is the cognitive ability of individuals to consider problems from the perspective of others, which is the opposite of egocentrism. Individuals with high perspective-taking ability are able to overcome egocentrism and to the take on the viewpoints of others to resolve problems. Several empirical studies have shown that perspective-taking can increase the level of attention to another5,6 and altruistic giving.31 Jun et al9 found in their research that individuals with social perspective-taking ability were better at looking at problems from the perspective of others and were more likely to trust others. It is difficult for an individual’s perspective-taking ability to change drastically in a short time, but visuo-spatial perspective-taking and social perspective-taking encourage individuals to temporarily overcome egocentrism and improve the level of interpersonal trust in others.

However, as indicated by Study 2, social perspective-taking had different effects on interpersonal trust under different contexts (competition vs cooperation). Study 2 shows that under the context of competition, social perspective-taking reduced interpersonal trust, whereas under the context of cooperation, social perspective-taking increased interpersonal trust. These results are consistent with the study by Epley et al,15 in which the effects of perspective-taking on prosocial behavior differed based on the context of competition vs cooperation. Under the context of competition, the manipulation of social perspective-taking will lead to reactive egotism. Reactive egotism refers the process of interaction in which the individual believes the other partner will have an egocentric orientation, which causes the individual to pay more attention to their interests while ignoring or disregarding the partner’s interest.15 Under the context of cooperation, the individual feels that the welfare of the partner as well as his own welfare, is critical, which is likely to increase interpersonal trust.19 Social perspective-taking could increase the perceived trust of cooperative partners and thus further enhance interpersonal trust. Thus, social perspective-taking is an effective method to improve interpersonal trust; however, contextual factors need to be considered in order to better promote interpersonal harmony.

The results of Study 3 showed that benevolence mediated the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust. Under the competitive context, social perspective-taking reduced the perception of benevolence of the partner and, in turn, there was less interpersonal trust. Under the context of cooperation, social perspective-taking increased the perception of benevolence of the partner and, in turn, there was more interpersonal trust. The results supported our hypothesis and provided evidence that helps to better understand the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust. The model of trust20 proposes that ability, benevolence, and integrity are important to trust, and each characteristic can vary independently. This model has been the most widely used in previous studies involving the perception of trustworthiness of trust targets and has been confirmed by many researchers.24 Benevolence is the extent to which a trustee is believed to want to do good to the trustor. When an individual perceives the other person as benevolent, they will be more likely to trust the other person. Conversely, when an individual perceives the other person as non-benevolent, which means the person is perceived as being only concerned with their own interests, they will be more likely to not trust the other person. In a previous study, under the context of competition, the individual with a competitive motivational orientation would most likely expect a reliably malevolent intention from others.19 When participants perceived the other person had low benevolence, they showed more self-interested behavior.25 Under the cooperative context, the individual with a cooperative motivational orientation would expect the other person to also have a benevolent intention toward him.19 The prosocial behavior of individuals increased significantly after social perspective-taking.16 Social perspective-taking encourages individuals to amplify their perception of the intentions of others. Social perspective-taking under the cooperative context can improve the level of perceived benevolence of the cooperative partner, thereby contributing to interpersonal trust, whereas under the competitive context, social perspective-taking can have a negative effect on the perceived benevolence of the competitor, thereby decreasing interpersonal trust.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations in the present study should be noted. Firstly, we investigated social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust at the behavioral level. The neural mechanism of the brain was not explored. There is evidence that when the views of others were considered, the activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)32 and the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ)33 increased significantly, and the differences in the activation of these two brain regions were positively correlated with trust behavior.8 Future research could further explore the neural mechanisms underlying the relationship between perspective-taking and interpersonal trust. Second, this study only explored the role of social perspective-taking under the contexts of competition and cooperation. Future research should explore other contexts, such as within different intergroup relationships.

Conclusion

Social perspective-taking could increase interpersonal trust; however, the effect of social perspective-taking on interpersonal trust will differ depending on the context. Social perspective-taking could improve interpersonal trust under a cooperative context, while the degree of interpersonal trust will decrease under a competitive context. Moreover, benevolence plays a mediating role in the relationship between social perspective-taking and interpersonal trust. Social perspective-taking could influence the perception of benevolence and thereby, enhance or diminish interpersonal trust.

These results suggest that social perspective-taking is an effective method to improve interpersonal trust, but contextual factors need to be considered in order to better promote interpersonal harmony. Thus, specific contexts need to be taken into account when using perspective-taking to mediate conflict and reduce inter-group stereotyping.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the new (cross) discipline of philosophy and social science in Zhejiang province is a major support project (Award no. 19XXJC04ZD).

Author Contributions

Binghai Sun, Xiajun Yu, Xuhui Yuan, Changkang Sun, and Weijian Li designed this study. Changkang Sun and Xuhui Yuan collected and analyzed data. Binghai Sun, Xuhui Yuan, Changkang Sun, and Weijian Li wrote the English version of this manuscript. Xiajun Yu participated in drafting the paper and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Rousseau DM, Sitkin SB, Burt RS, et al. Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;23(3):393–404. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926617

2. Levine EE, Bitterly TB, Cohen TR, et al. Who is trustworthy? Predicting trustworthy intentions and behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018;115(3):468. doi:10.1037/pspi0000136

3. Jasielska D. The moderating role of kindness on the relation between trust and happiness. Curr Psychol. 2018;39(6):2065–2073. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9886-7

4. Helliwell J, Huang H, Wang S. The distribution of the world happiness. In: Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs G, editors. World Happiness Report. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2016:8–49.

5. Batson CD, Lishner DA, Stocks EL. The empathy—altruism hypothesis. In: Schroeder DA, Graziano WG, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior. Oxford library of psychology; 2015:259–281.

6. Surtees A, Apperly I, Samson D. Similarities and differences in visuo and spatial perspective-taking processes. Cogn. 2013;129(2):426–438. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2013.06.008

7. Fett A, Shergill SS, Gromann PM, et al. Trust and social reciprocity in adolescence-a matter of perspective-taking. J Adolesc. 2014;37(2):175–184. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.011

8. van den Bos W, van Dijk E, Westenberg M, et al. Changing brains, changing perspectives: the neurocognitive development of reciprocity. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(1):60–70. doi:10.1177/0956797610391102

9. Jun D, Shuying FU, Yang W, et al. Influence of self-control on interpersonal trust: analysis of multiple mediation effect. Stu Psychol Behav. 2018;16(2):225–230.

10. Yue Z, Xianliang G, Zhiqiang T, et al. Level-1 and level-2 spatial perspective taking: an overview of behavioral research and theories. J Psychol Sci. 2018;41(02):504–510.

11. Surtees ADR, Apperly IA, Samson D. The use of embodied self-rotation for visual and spatial perspective-taking. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7(05):698. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00698

12. Ku G, Wang CS, Galinsky AD. Perception through a perspective-taking lens: differential effects on judgment and behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(5):792–798. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.001

13. Erle TM, Ruessmann JK, Topolinski S. The effects of visuo-spatial perspective-taking on trust. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;79(11):34–41. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2018.06.006

14. Balconi M, Crivelli D, Vanutelli ME. Why to cooperate is better than to compete: brain and personality components. BMC Neurosci. 2017;18(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12868-017-0386-8

15. Epley N, Caruso E, Bazerman MH. When perspective taking increases taking: reactive egoism in social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(5):872–889. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.872

16. Pierce JR, Kilduff GJ, Galinsky AD, et al. From glue to gasoline: how competition turns perspective takers unethical. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(10):1986–1994. doi:10.1177/0956797613482144

17. Todd AR, Galinsky AD. Perspective‐taking as a strategy for improving intergroup relations: evidence, mechanisms, and qualifications. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014;8(7):374–387. doi:10.1111/spc3.12116

18. Tian L, Zhang X, Huebner ES. The effects of satisfaction of basic psychological needs at school on children’s prosocial behavior and antisocial behavior: the mediating role of school satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2018;9(4):548. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00548

19. Deutsch M. The effect of motivational orientation upon trust and suspicion. Hum Rela. 1960;13(2):123–139. doi:10.1177/001872676001300202

20. Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad Manage Rev. 1995;20(3):709–734. doi:10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

21. Galinsky AD, Wang CS, Ku G. Perspective takers behave more stereotypically. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(2):404–419. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.404

22. Colquitt JA, Scott BA, LePine JA. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):909–927. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

23. Pei W, Liang Y, Yu L, et al. The effects of characteristic perception and relationship perception on interpersonal trust. Adv Psychol Sci. 2016;24(5):815. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.00815

24. Pesch A, Suárez S, Koenig MA. Trusting others: shared reality in testimonial learning. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;23(10):38–41. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.009

25. Caruso EM, Epley N, Bazerman MH. The good, the bad, and the ugly of perspective taking in groups. In: Tenbrunsel AE, editor. Ethics in Groups (Research on Managing Groups and Teams, Vol. 8). Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2006:201–224.

26. Shih MJ, Stotzer R, Gutiérrez AS. Perspective-taking and empathy: generalizing the reduction of group bias towards Asian Americans to general outgroups. Asian Am J Psychol. 2013;4(2):79–83. doi:10.1037/a0029790

27. Gong Z, Tang Y, Liu C. Can trust game measure trust? Adv Psychol Sci. 2021;29(1):19. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2021.00019

28. Barber SJ, Rajaram S, Aron A. When two is too many: collaborative encoding impairs memory. Mem Cognit. 2010;38(3):255–264. doi:10.3758/MC.38.3.255

29. Mayer RC, Davis JH. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: a field quasi-experiment. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(1):123–136. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.123

30. Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Meas. 2013;51(3):335–337.

31. Tusche A, Böckler A, Kanske P, et al. Decoding the charitable brain: empathy, perspective taking, and attention shifts differentially predict altruistic giving. J Neurosci. 2016;36(17):4719–4732. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3392-15.2016

32. Healey ML, Grossman M. Cognitive and affective perspective-taking: evidence for shared and dissociable anatomical substrates. Front Neurol. 2018;9(6):491. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00491

33. Coll MP, Tremblay MPB, Jackson PL. The effect of tDCS over the right temporo-parietal junction on pain empathy. Neuropsychologia. 2017;100(6):110–119. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.04.021

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.