Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

The Cost of Repaying Trust: Examining Psychological Detachment as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Feeling Trusted and Work–Family Conflict

Authors Li J , Xu S, Chen Y, Ye M

Received 20 March 2021

Accepted for publication 8 July 2021

Published 17 July 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1053—1062

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S312008

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Jiamin Li,1,* Shujun Xu,2,* Yushuai Chen,2 Maolin Ye1

1School of Management, Jinan University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Applied Psychology, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Maolin Ye

School of Management, Jinan University, No. 601 Huangpu Road, Guangzhou, 510632, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 13827101319

Email [email protected]

Background: Research on the “dark side” of feeling trusted has mainly focused on the workplace, paying much less attention to the non-work domain. Using social exchange theory as a basis, this research explored the effect of feeling trusted on work–family conflict and its underlying mechanisms.

Methods: Data were collected in two waves from 375 full-time employees from companies in different industries in China and path analysis was used to test our hypotheses.

Results: The results showed that psychological detachment mediated the relationship between feeling trusted and work–family conflict. This mediating effect was moderated by positive reciprocity beliefs, with the effect being stronger for employees with strong (vs weak) positive reciprocity beliefs.

Conclusion: This study advances research on the negative effects of feeling trusted, indicating that while it might be important for employees to repay supervisors’ trust, they also need to clearly delineate the boundary between work and family to reduce work–family conflict.

Keywords: feeling trusted, positive reciprocity beliefs, psychological detachment, social exchange theory, work–family conflict

Introduction

Trust, an important component of interpersonal relationships within the workplace,1–3 is an important topic of management research. Early research in this area mainly focused on employees’ trust in supervisors, reporting that employees with higher levels of trust tend to have greater job satisfaction and organizational commitment.4 However, scholars have begun to realize that studying only employees’ trust in supervisors does not reveal the whole picture of trust in the supervisor–subordinate relationship, because employees can in turn feel trusted by supervisors.5–7 Hence, the extent to which a subordinate or employee feels trusted by a supervisor, ie, perceives the supervisor as willing to be vulnerable to the employee’s actions, has attracted increasing research attention in recent years.8 Research has found that feeling trusted may benefit employees by enhancing their job engagement,9 task performance, and organizational citizenship behavior.10

However, just like two sides of a same coin, feeling trusted is not always beneficial; recent studies have drawn attention to its dark side and found that it can also be costly.8 While this research has offered valuable insights into the negative aspects of feeling trusted in the workplace, it has been limited to the work environment, paying little attention to the important link between feeling trusted and the non-work domain. This lack of understanding is problematic because research has found that employees who feel trusted are likely to have a heavier workload.8 Employees who expend significant amounts of energy at work find themselves with less energy when they return home, and may thus lead to work–family conflict (a form of interrole conflict in which role pressures from the work and family domains are incompatible in some respects).10–13 Without exploring the effect of feeling trusted on work–family conflict will fail to fully reveal the dark side of feeling trusted. In addition, research has shown that work–family conflict can impede employees’ performance in both work and non-work domains.14 Investigating the antecedents of work–family conflict is vital to avoid the emergence and development of such conflict in practice.15 Thus, for both theoretical and practical reasons, we believe that it is imperative to explore the effect of feeling trusted on work–family conflict and the potential mechanism underlying this relationship.

In exploring this issue, our research contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we add to the literature on feeling trusted by extending discussion of negative outcomes from the workplace to the family. Second, we provide a theoretical framework for explaining how and why work–family conflict is affected by feeling trusted. We draw on social exchange theory to develop a mediation pathway that links feeling trusted with work–family conflict via psychological detachment. Specifically, we suggest that employees who feel trusted are less likely to achieve psychological detachment from work, which in turn increases their work–family conflict. Finally, we examine how personal characteristics, particularly positive reciprocity beliefs, can systematically influence the effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment and the mediating effect of psychological detachment. By doing so, we reveal when and how feeling trusted can affect work–family conflict through psychological detachment.

Theoretical Framework

Social exchange theory provides a useful lens for understanding how feeling trusted may generate work–family conflict. This theory suggests that the relationships between individuals represent a type of exchange.16 People follow the principle of reciprocity in the exchange process; that is, when they are given resources by others, they feel morally obliged to return those benefits in some way.17 Such exchange may be material (eg, wages) or social (eg, trust, support, and advice). A great deal of organizational behavior research has shown that social exchange theory is applicable in the workplace.18–20 For example, research has found that in high-quality leader–member exchange relationships, supervisors tend to allocate more resources and support to their subordinates. Subsequently, the subordinates feel an obligation to reciprocate, thereby improving their work performance and organizational commitment.21

Hypotheses Development

The Mediating Role of Psychological Detachment

Based on social exchange theory, we expect psychological detachment may mediate the relationship between feeling trusted and work–family conflict. Psychological detachment implies that employees not only change location when they leave the workplace but also take a break from thinking about work.22

In the workplace, supervisors often determine the benefits that employees receive in terms of salary, promotion, and other opportunities.23,24 As a result, employees may seek to maintain strong social exchange relationships with their supervisors to secure these benefits.9 When employees are aware of their supervisors’ trust in them, based on their perceived obligation to repay this trust, they are more willing to meet their supervisors’ expectations and put extra effort into accomplishing assigned tasks.25 In such cases, employees may bring their work home and continue to engage in work-related tasks during non-working hours. Even if employees do not carry out work-related tasks at home, they may be thinking about the day’s work or the next day’s work, making it difficult for them to achieve complete psychological detachment from work.22 We therefore hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1. Feeling trusted is negatively related to psychological detachment.

Moreover, when employees have a lower level of psychological detachment, the boundary between work and non-work becomes blurred. Consequently, any negative affect and stress felt by employees at work are more likely to spill over to the family domain, affecting family life and generating work–family conflict.26 In addition, if employees cannot achieve psychological detachment during non-working hours, they may be less involved in family life, making it difficult for them to assume their family role and fulfill their role obligations, also resulting in work–family conflict. Therefore, a low level of psychological detachment is expected to increase work–family conflict. We thus proposed:

Hypothesis 2. Psychological detachment is negatively related to work–family conflict.

Integrating Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, we further propose:

Hypothesis 3. Feeling trusted has a positive indirect effect on work–family conflict via psychological detachment.

The Moderating Role of Positive Reciprocity Beliefs

In addition, interaction does not always take place in a quid pro quo fashion;27 that is, one’s efforts are not always rewarded by others. Therefore, we further inferred that there may exist a moderating variable that determines the strength of the effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment. We focused on positive reciprocity beliefs (an individual difference variable) as a possible moderator, which reflect the degree to which individuals endorse reciprocity in exchange relationships.27,28

Individuals with strong positive reciprocity beliefs try to maintain long-term high-quality relationships with exchange partners through reciprocity.28,29 Failing to reciprocate leads to feelings of indebtedness.30 In contrast, individuals with a low level of positive reciprocity beliefs may feel little obligation to reciprocate behavior, regardless of what they receive from their exchange partners.27 These arguments suggest that when feeling trusted by supervisors, employees who hold stronger positive reciprocity beliefs are more likely to feel obligated and put extra effort into repaying their supervisors’ trust,16,31 which weakens their psychological detachment from work. In contrast, employees who do not hold strong positive reciprocity beliefs feel little obligation to repay supervisors’ trust, and so are less likely to put excess effort into their work in non-work time, leading to greater psychological detachment. Hence, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 4. The negative effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment is moderated by positive reciprocity beliefs, such that the relationship is stronger when positive reciprocity beliefs is high (vs low).

The basic tenet of social exchange theory is that in a binary relationship, if something is given, there is a silent promise that something of equivalent value will be returned.16,17 Employees who feel trusted believe that their supervisors have positive expectations of them, which boosts their pride and represents a psychological resource gain.8 Influenced by the norm of reciprocity, employees feel obliged to repay the trust of supervisors and thus may devote themselves to working overtime, leading to low psychological detachment and further triggering work–family conflict. In addition, the above process depends on the level of employees’ positive reciprocity beliefs. When the level of positive reciprocity beliefs is high, employees who feel trusted have a stronger motivation to repay their supervisors, thereby triggering lower psychological detachment and work–family conflict. We created our theoretical model (see Figure 1) by developing a moderated mediation hypothesis integrating all of the important variables:

Hypothesis 5. The positive indirect effect of feeling trusted on work–family conflict via psychological detachment is moderated by positive reciprocity beliefs, such that the positive indirect effect is stronger when the level of positive reciprocity beliefs is high (vs low).

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Method

Participants and Procedure

A snowball sampling method was used to recruit participants. Specifically, we contacted several alumni who were full-time employees from different companies in China through alumni networks and asked them to invite their coworkers to participate in our study. Overall, we invited 500 employees from different companies to participate in our research. Two phases of data collection were carried out. Each participant who completed both phases of the survey received ¥10 as a gift. To guarantee confidentiality, we identified each participant by a code and used the resulting codes to match the two phases of data.

Each of the two stages was separated by 2 weeks. In the initial phase (Time 1), we distributed 500 questionnaires to the participants, asking them to provide data on their demographic characteristics (eg, age, gender, tenure in their organization), the extent to which they felt trusted by their supervisors, and their positive reciprocity beliefs. A total of 458 participants returned valid questionnaires, yielding a response rate of 91.60%. In the second phase (Time 2), these 458 participants were sent additional questionnaires and asked to rate their psychological detachment and work–family conflict. A total of 375 participants returned the second questionnaires, giving a response rate of 81.88%. Therefore, our final sample comprised 375 participants with matched data from both phases. We attempted to determine whether there were any significant differences between the participants who completed both the Time 1 and the Time 2 questionnaires and those who did not. A t-test revealed that the difference between the two groups of participants had a non-significant influence on feeling trusted (t (456) = −1.55, p =0.12) and positive reciprocity beliefs (t (456) = −1.49, p = 0.14).

Of the 375 employees in the final sample, 60.3% were female and the average age was 33.13 years (SD = 6.77) and 56.5% employees have one or more children. They had worked for their current organizations for an average of 5.48 years (SD = 4.58).

Measures

Two researchers who were proficient in both Chinese and English translated the questionnaires into Chinese using the translation–back-translation procedure.32 Specifically, the original questionnaires were first translated by the first author into Chinese versions, which were then back-translated into English by a bilingual linguist. Subsequently, we compared the back-translated versions with the original ones to ensure their consistency.

Feeling Trusted (T1)

Feeling trusted was assessed using a four-item scale proposed by Lau et al.33 An example item is “Empowering me with great decision-making power.” The items were measured on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.80.

Positive Reciprocity Beliefs (T1)

We employed a nine-item scale developed by Perugini, Gallucci, Presaghi and Ercolani (2003) to assess the participants’ positive reciprocity beliefs.34 A sample item is “I am ready to undergo personal costs to help somebody who helped me before.” The items were measured on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.90.

Psychological Detachment (T2)

The participants were asked to complete a four-item scale developed by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) to assess their psychological detachment from work.35 A sample item is “During time after work, I distance myself from my work.” The items were measured on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.85.

Work–Family Conflict (T2)

We used a five-item scale developed by Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian (1996) to measure work–family conflict.36 A sample item is “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.” The items were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.92.

Control Variables

For consistency with previous research on work–family conflict,13,37 we controlled for the respondents’ age, gender, tenure (in years) at the organization, and whether they had children to reduce the possibility of spurious results. We controlled for age because it generally relates to career–life stage, which we hypothesized may play a role in the extent of work–family conflict experienced.38 Likewise, we controlled for gender because males and females may experience different levels of work–family conflict.39 We controlled for differences in tenure because research has suggested that employees may take time to adapt to a new workplace.40 We also controlled for whether the participants had children, because stress associated with parenting may limit people’s capacity to fulfill their family roles.41

Analytic Strategy

Path analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses using Mplus 8.1.42 To reduce the risk of multicollinearity, the predictors (ie, feeling trusted and positive reciprocity beliefs) were mean-centered.43 We also used bootstrapping to estimate the confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects and to assess the differences between the indirect effects at different levels of the moderating variable.42

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliability scores of the variables used in our research. Feeling trusted was negatively correlated with psychological detachment (r = −0.19, p < 0.001) and psychological detachment was negatively correlated with work–family conflict (r = −0.19, p < 0.001). These correlation results provided preliminary support for our hypotheses.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics |

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to assess the discriminant validity of the key variables. As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized four-factor model fitted the data better than any of the other models (χ2(203) = 552.56, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.06), indicating that the four variables were distinct from each other and represented four different constructs.

|

Table 2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results |

Hypothesis Tests

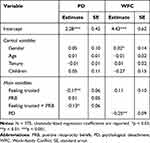

Table 3 presents the results of the path analysis. The results showed that feeling trusted had a significant negative effect on psychological detachment (b = −0.17, p = 0.003), Moreover, psychological detachment was negatively correlated with work–family conflict (b = −0.26, p = 0.005). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 and 2 were supported.

|

Table 3 Path Analysis Results |

To further test the indirect effect of psychological detachment, we conducted bootstrapping (with 20,000 bootstrap samples) to estimate the CIs of the indirect effect. The estimated size of the indirect effect was 0.04, and the 95% bias corrected CI was [0.01, 0.10]. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

In Hypothesis 4, we posited that positive reciprocity beliefs moderate the relationship between feeling trusted and psychological detachment, such that the effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment is stronger when positive reciprocity beliefs are high rather than low. As shown in Table 3, we found that the interaction between feeling trusted and positive reciprocity beliefs was significantly and negatively correlated with psychological detachment (b = −0.13, p = 0.026). Figure 2 shows a graphical illustration of the moderating effect of positive reciprocity beliefs on the relationship between feeling trusted and psychological detachment. A simple slope analysis revealed that the negative effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment was significant when the level of positive reciprocity beliefs was high (simple slope = −0.30, p = 0.000), but when the level of positive reciprocity beliefs was low, the analysis revealed a non-significant effect of feeling trusted on psychological detachment (simple slope = −0.03, p = 0.782). Hence, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

|

Figure 2 The interactive effect of feeling trusted and positive reciprocity beliefs on psychological detachment. |

Finally, to test the integrated model, we used bootstrapping to estimate the 95% CIs of our proposed indirect effects under different levels of positive reciprocity beliefs. The results revealed that psychological detachment mediated the link between feeling trusted and work–family conflict when the level of positive reciprocity beliefs was high (indirect effect = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.16]), but not when it was low (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI = [−.04, 0.07]). The difference between the two indirect effects at plus or minus one standard deviation of positive reciprocity beliefs was also significant (difference = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.18]). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Discussion

Research has indicated that feeling trusted is related to positive work outcomes for employees, such as enhanced task performance, job engagement and organizational citizenship behavior.9,10 However, studies have also found that feeling trusted may have negative work outcomes.8,44 We extended this research by exploring whether feeling trusted may also be related to negative outcomes in employees’ family domain (beyond the immediate workplace context). Grounded in social exchange theory and across a two-wave field study, we found that employees who felt trusted were more likely to go the extra mile, leading to lower psychological detachment and ultimately work–family conflict. Furthermore, we found that the relationship between feeling trusted and psychological detachment was moderated by positive reciprocity beliefs, which reflect the degree to which individuals endorse reciprocity in exchange relationships.27,28 Finally, our findings indicate that the mediating effect of psychological detachment is stronger among employees who hold higher positive reciprocity beliefs. This verified model has multiple implications for theory and practice.

Theoretical Implications

Our findings contribute to the literature in three ways. First, our research contributes to the literature on feeling trusted by offering a richer picture of the negative effects that feeling trusted may have on employees. Prior research has found that feeling trusted can benefit both organizations and employees.9,10,25 However, focusing on the positive effect of feeling trusted can mask the underlying costs. Recently, scholars have begun to focus on the dark side of feeling trusted and to challenge the prevailing conclusion that feeling trusted is always beneficial.8,44 However, this research has mainly focused on work-related outcomes, overlooking the non-work domain. To address this limitation, our research examined the effect of feeling trusted on work–family conflict, thus providing further insights into the negative effects of feeling trusted.

Second, our research contributes to understanding of the antecedents of work–family conflict. Research has found that some negative work-related factors, such as workplace bullying, passive leadership, and financial insecurity, can increase work–family conflict.12,45,46 However, those studies have not fully revealed the source of work–family conflict, because sometimes negative outcomes can be triggered by positive events.47,48 Following this logic, we explored and identified an important positive antecedent of work–family conflict (ie, feeling trusted), thereby enriching understanding of the causes of work–family conflict.

Finally, our conclusions shed light on the mechanism underlying the relationship between feeling trusted and work–family conflict. As research exploring the impact of feeling trusted on employees’ work–family conflict is limited, the potential mechanism of this impact remains unclear. Therefore, these findings enrich knowledge of the potential underlying mechanism, showing why and when feeling trusted may increase work–family conflict. In line with social exchange theory, we conjectured that employees who hold stronger positive reciprocity beliefs feel more obligated to reciprocate others’ positive behavior toward them, such as by repaying supervisors’ perceived trust in them. This may in turn cause employees to invest more time and effort in work, resulting in decreased psychological detachment from work while at home. This reduction in psychological detachment weakens their commitment to their family role, which can generate work–family conflict. Thus, our research paints a more complete picture of when and why feeling trusted can lead to work–family conflict for employees.

Practical Implications

Increasing numbers of employees are confronted with work–family conflict. Research has suggested that work–family conflict has negative effects on employees’ physical and mental health and family harmony, as manifested by job burnout, a weakening of the quality of marital relationships, and poorer life satisfaction.49–51 It is therefore of great practical importance to discover the cause for this conflict. Our research suggests that feeling trusted is a key driver of work–family conflict, particularly in employees with stronger positive reciprocity beliefs. These findings have the following implications for management practice. First, although it is important for employees to repay supervisors’ trust with excellent work performance, they should also be guided to manage their time effectively. Specifically, employees should be encouraged to complete their work tasks efficiently during working hours and avoid bringing work home where possible, as this may engender unnecessary work–family conflict. Second, when supervisors trust their employees, they should remind them to maintain clear boundaries between work and family, because reducing the overlap between these domains can ease the risk of work–family conflict. Third, supervisors should exhibit role modeling behavior for their employees, who tend to regard those higher in the organizational hierarchy as examples to imitate and learn from. Employees are likely to perceive a clear separation between work and family if their supervisors model such a perception.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study, similar to most research, is not without limitations.

First, all of the variables were self-reported by the participants, which may have resulted in common method bias.52 We measured our research variables at two time points to minimize this problem, but future researchers seeking to replicate our findings could consider collecting data from multiple sources to further reduce the likelihood of common method bias.

Second, although we collected our data at two time points, our research design did not allow us to draw causal inferences. Therefore, future research should consider examining the identified effects in a laboratory experiment or an intervention study to allow stronger causal inferences to be made. For example, future research could use experimental methods to manipulate feeling trusted before measuring employees’ psychological detachment levels.

Third, we focused only on the boundary conditions of individual factors (ie, positive reciprocity beliefs), yet some situational factors may also moderate the relationship between feeling trusted and psychological detachment, such as the perceived segmentation norm.53 Employees working in an organization with a stronger segmentation norm are less likely to tolerate work-related interruptions to their family life. Future studies could further explore these moderators to provide greater insight into the relationship between feeling trusted and work–family conflict.

Finally, factors other than our control variables may influence work–life conflict. Hence, future research could use control variables such as marital status, role conflict, and the nature of employment to more precisely interpret the relationship between feeling trusted and work–family conflict.

Conclusions

Together, our findings showed that feeling trusted by supervisors can affect employees’ work–family conflict through psychological detachment. We also advanced that positive reciprocity beliefs can moderated this linkage. Specifically, when the level of positive reciprocity beliefs was stronger (vs weak), the mediating effect of psychological detachment was stronger. These findings not only contribute to research on the dark side of feeling trusted by supervisors but also advise that employees should try their best to detach themselves from work during non-working hours to reduce work–family conflict.

Ethics and Consent Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of Management School of Jinan University and in line with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was done with the permission of the companies involved.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in our study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was supported by the grants funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 72002050).

Disclosure

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Dirks KT, Ferrin DL. The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ Sci. 2001;12(4):450–467. doi:10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

2. Gambetta D. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. New York, NY: Basil Blackwell; 1988.

3. Rousseau DM, Sitkin SB, Burt RS, Camerer C. Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad Manag Rev. 1998;23(3):393–404. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926617

4. Dirks KT, Ferrin DL. Trust in leadership: meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):611–628. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611

5. Brower HH, Schoorman FD, Tan HH. A model of relational leadership: the integration of trust and leader–member exchange. Leadersh Q. 2000;11(2):227–250. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00040-0

6. Korsgaard MA, Brower HH, Lester SW. It isn’t always mutual: a critical review of dyadic trust. J Manage. 2015;41(1):47–70. doi:10.1177/0149206314547521

7. Lester SW, Brower HH. In the eyes of the beholder: the relationship between subordinates’ felt trustworthiness and their work attitudes and behaviors. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2003;10(2):17–33. doi:10.1177/107179190301000203

8. Baer MD, Dhensa-Kahlon RK, Colquitt JA, Rodell JB, Outlaw R, Long DM. Uneasy lies the head that bears the trust: the effects of feeling trusted on emotional exhaustion. Acad Manag J. 2015;58(6):1637–1657. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0246

9. Skiba T, Wildman JL. Uncertainty reducer, exchange deepener, or self-determination enhancer? Feeling trust versus feeling trusted in supervisor-subordinate relationships. J Bus Psychol. 2019;34(2):219–235. doi:10.1007/s10869-018-9537-x

10. Cho J, Schilpzand P, Huang L, Paterson T. How and when humble leadership facilitates employee job performance: the roles of feeling trusted and job autonomy. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2020;28(2):169–84.

11. Byron K. A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. J Vocat Behav. 2005;67(2):169–198. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

12. Che XX, Zhou ZE, Kessler SR, Spector PE. Stressors beget stressors: the effect of passive leadership on employee health through workload and work–family conflict. Work Stress. 2017;31(4):338–354.c. doi:10.1080/02678373.2017.1317881

13. Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manag Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

14. Amstad FT, Meier LL, Fasel U, Elfering A, Semmer NK. A meta‐analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross‐domain versus matching‐domain relations. J Occup Health Psychol. 2011;16:151–169. doi:10.1037/a0022170

15. Zhou ZE, Meier LL, Spector PE. The spillover effects of coworker, supervisor, and outsider workplace incivility on work‐to‐family conflict: a weekly diary design. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(9–10):1000–1012. doi:10.1002/job.2401

16. Blau P. Power and Exchange in Social Life. NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1964.

17. Gouldner AW. The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am Sociol Rev. 1960;25(2):161–178. doi:10.2307/2092623

18. Akhtar M. High‐performance work system and employee performance: the mediating roles of social exchange and thriving and the moderating effect of employee proactive personality. Asia Pac J Hum Resour. 2019;57(3):365–369.

19. Choi W, Kim SL, Yun S. A social exchange perspective of abusive supervision and knowledge sharing: investigating the moderating effects of psychological contract fulfillment and self-enhancement motive. J Bus Psychol. 2019;34(3):305–319. doi:10.1007/s10869-018-9542-0

20. Reader TW, Mearns K, Lopes C, Kuha J. Organizational support for the workforce and employee safety citizenship behaviors: a social exchange relationship. Human Relations. 2017;70(3):362–385. doi:10.1177/0018726716655863

21. Lee A, Gerbasi A, Schwarz G, Newman A. Leader–member exchange social comparisons and follower outcomes: the roles of felt obligation and psychological entitlement. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2019;92(3):593–617. doi:10.1111/joop.12245

22. Sonnentag S, Bayer UV. Switching off mentally: predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. J Occup Health Psychol. 2005;10(4):393–414. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.393

23. Hollensbe EC, Khazanchi S, Masterson SS. How do I assess if my supervisor and organization are fair? Identifying the rules underlying entity-based justice perceptions. Acad Manag J. 2008;51(6):1099–1116. doi:10.5465/amj.2008.35732600

24. Mitchell MS, Ambrose ML. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):1159–1168. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159

25. Lau DC, Lam LW, Wen SS. Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: a self-evaluative perspective. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(1):112–127. doi:10.1002/job.1861

26. Ilies R, Schwind KM, Wagner DT, Johnson MD, DeRue DS, Ilgen DR. When can employees have a family life? The effects of daily workload and affect on work-family conflict and social behaviors at home. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(5):1368–1379. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1368

27. Umphress EE, Bingham JB, Mitchell MS. Unethical behavior in the name of the company: the moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(4):769–780. doi:10.1037/a0019214

28. Zou WC, Tian Q, Liu J. Servant leadership, social exchange relationships, and follower’s helping behavior: positive reciprocity belief matters. Int J Hosp Manag. 2015;51:147–156. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.08.012

29. Eisenberger R, Lynch P, Aselage J, Rohdieck S. Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(6):787–799. doi:10.1177/0146167204264047

30. Shen H, Wan F, Wyer RS. Cross-cultural differences in the refusal to accept a small gift: the differential influence of reciprocity norms on Asians and North Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(2):271–281. doi:10.1037/a0021201

31. Dulebohn JH, Bommer WH, Liden RC, Brouer RL, Ferris GR. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J Manage. 2012;38(6):1715–1759. doi:10.1177/0149206311415280

32. Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Crosscultural Psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1980:389–444.

33. Lau DC, Liu J, Fu PP. Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pac J Manag. 2007;24(3):321–340. doi:10.1007/s10490-006-9026-z

34. Perugini M, Gallucci M, Presaghi F, Ercolani AP. The personal norm of reciprocity. Eur J Pers. 2003;17(4):251–283. doi:10.1002/per.474

35. Sonnentag S, Fritz C. The recovery experience questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;12(3):204–221. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204

36. Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–410. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

37. Golden TD, Veiga JF, Simsek Z. Telecommuting’s differential impact on work-family conflict: is there no place like home? J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(6):1340–1350. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1340

38. Martins L, Eddleston KA, Veiga JF. Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Acad Manag J. 2002;45:399–409.

39. Parasuraman S, Greenhaus JH. Toward reducing some critical gaps in work–family research. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2002;12:299–312. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00062-1

40. Bailey DE, Kurland NB. A review of telework research: findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J Organ Behav. 2002;23(4):383–400. doi:10.1002/job.144

41. Voydanoff P. Work role characteristics, family structure demands, and work/family conflict. J Marriage Fam. 1988;50(3):749–761. doi:10.2307/352644

42. Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):1–22. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

43. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

44. Wang H, Huang Q. The dark side of feeling trusted for hospitality employees: an investigation in two service contexts. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;76:122–131. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.001

45. Odle‐Dusseau HN, Matthews RA, Wayne JH. Employees’ financial insecurity and health: the underlying role of stress and work–family conflict appraisals. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2018;91(3):546–568. doi:10.1111/joop.12216

46. Raja U, Javed Y, Abbas M. A time lagged study of burnout as a mediator in the relationship between workplace bullying and work–family conflict. Int J Stress Manag. 2018;25(4):377–390. doi:10.1037/str0000080

47. Koopman J, Lanaj K, Scott BA. Integrating the bright and dark sides of OCB: a daily investigation of the benefits and costs of helping others. Acad Manag J. 2016;59(2):414–435. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0262

48. Qin X, Chen C, Yam KC, Huang M, Ju D. The double-edged sword of leader humility: investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(7):693–712. doi:10.1037/apl0000456

49. Adams GA, King LA, King DW. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):411–420. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411

50. Matthews LS, Conger RD, Wickrama KAS. Work-family conflict and marital quality: mediating processes. Soc Psychol Q. 1996;59(1):62–79. doi:10.2307/2787119

51. Wang Y, Chang Y, Fu J, Wang L. Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese female nurses: the mediating effect of psychological capital. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-915

52. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63(1):539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

53. Kreiner G. Consequences of work–home segmentation or integration: a person-environment fit perspective. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(4):485–507. doi:10.1002/job.386

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.