Back to Journals » Clinical Optometry » Volume 7

Strategies to help patients stop smoking: the optometrist's perspective

Received 31 May 2015

Accepted for publication 14 July 2015

Published 25 November 2015 Volume 2015:7 Pages 103—113

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S63185

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Mr Simon Berry

Ryan David Kennedy,1,2 Ornell Douglas2

1Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Institute for Global Tobacco Control, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; 2Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Abstract: The following review article discusses tobacco's toll on individual and public health, and presents what is currently known about cigarette smoking's risk to ocular health. The article also discusses what eye care professionals – specifically optometrists – can do to help address tobacco use with their patients. Smoking is a leading preventable cause of age-related macular degeneration, and is also causally associated with the development of cataract, thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy, and uveitis. Smoking's causal association with vision loss is now used in some countries' health warning labels that appear on tobacco products and national social marketing materials including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Despite this uptake in health promotion education, very few eye care professionals regularly engage their patients in discussions about tobacco use. Optometrists can be a helpful addition to a smoking cessation health care network that already involves more than a dozen health care professions including medicine, nursing, pharmacy, dentistry, and dental hygiene. Optometrists can further play an important role in educating younger non-smoking patients about the risk of smoking and vision loss to support tobacco-use prevention. Optometrists report that they feel that addressing tobacco use is "not their job" or argue that this is more appropriately done by a family physician/general practitioner. This review article presents the rationale that all primary care providers have a role and a responsibility to discuss tobacco use with their patients. This review article outlines some techniques and strategies that optometrists can use to begin important discussions with their patients about tobacco use, to both support prevention and cessation efforts to support healthy ocular systems and improve public health. Further strategies that health care practitioners use to either connect patients with cessation services, or strategies that practitioners can deliver are also outlined.

Keywords: smoking, tobacco use, prevention, cessation, age-related macular degeneration

Introduction

Tobacco use continues to be the leading cause of death and disease in the world

It is well understood that tobacco use has had a profound impact on public health although the scale and scope of the impact may be less well known. Tobacco use killed 100 million people in the 20th century.1 Today, tobacco use causes globally over five million deaths annually.2,3

In addition to contributing to chronic diseases including cancers and ischaemic heart disease, smoking is an important risk factor for communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and lower respiratory infections.4,5 Tobacco use exacerbates other non-communicable diseases, as well as mental illnesses and other substance abuse problems including alcoholism. Tobacco production, manufacturing, and distribution each damage the environment and have been highlighted as a hindrance to human development.1

There have been important gains in tobacco control in many countries around the world. However, tobacco use continues to be the single most prevalent cause of death, disease, and disability globally.1,6 In the years to come, tobacco’s toll on public health is expected to deepen. By the year 2030, tobacco use will cause eight million deaths or 10% of all global deaths. If current patterns of smoking continue over the 21st century, over one billion people will die from tobacco use.7,8

Tobacco-use initiation and prevalence

In developed countries where the tobacco industry has operated for more than 100 years, there is generally declining prevalence of tobacco use; however, substantial differences in smoking prevalence by education level have persisted over the last decade.9 Globally, people with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to smoke, men smoke more than women, people living with mental illness are nearly twice as likely to smoke as other persons, and although data are not available globally, where studies have been conducted, people from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community are also much more likely to smoke.1

Although initiation rates differ slightly between countries, the majority of tobacco users start using tobacco before the age of 18. In Canada in 2012, the mean age at which ever-smokers, age 25 and over, smoked their first full cigarette was 16.4, with 95% of respondents reporting between ages 9 and 25 (Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, Statistics Canada, unpublished data, 2015).9

Tobacco users want to quit

Approximately 80% of adult smokers in developed countries report that they want to quit, and approximately half report that they try to quit in any given year.10 This study of adult smokers in Canada, the US, the UK, and Australia reported that the proportion of smokers who agreed or agreed strongly with the statement ‘‘If you had to do it over again, you would not have started smoking’’ was approximately 90%, and across the four countries.10

Tobacco control policies and health care providers

To help address the global epidemic of tobacco use, the global health community, through the World Health Assembly, negotiated a global treaty on tobacco control. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) was the world’s first global health treaty, and is one of the world’s most successful treaties with 180 parties as of 2015.11 The FCTC requires member parties to adopt policies that protect citizens from exposure to tobacco smoke, and other public health strategies including awareness campaigns, other health communication strategies, and appropriate training for health professionals to better communicate the health effects of tobacco use with their patients. These strategies are important because smokers with greater knowledge of the broad range of health effects of smoking are more likely to quit and remain abstinent.12

The American Medical Association recommends that all primary health care providers ask patients as young as 10 years about their tobacco use to encourage both prevention and cessation. The US Prevention Services Task Force recommends that all primary care clinicians provide interventions to prevent initiation of tobacco use among school-aged children and adolescents.13 There is evidence that these types of primary care relevant interventions can prevent smoking initiation with children and adolescents.14

Despite direct calls for health care providers to engage their patients on the issue of tobacco use, there are many countries in the world where primary care physicians are not talking to their patients about tobacco. One study that examined advice from health care providers in 15 different countries revealed that among smokers who did visit a health care provider, provision of advice to quit varied greatly, the proportion of respondents who visited a doctor and got advice to quit using tobacco ranged from greater than 50% in the US to less than 30% in the UK, and less than 10% in the Netherlands.15 The health care providers were not specified, the respondents were asked “Have you visited a doctor or other health professional since last survey date?” so it is unclear if respondents would include eye health specialists.

There are numerous reasons for optometrists to be engaged with their patients around tobacco use, both to support prevention and cessation. Table 1 summarizes the findings from the introduction.

| Table 1 Things to consider when optometrists discuss tobacco use with their patients |

Smoking’s impact on ocular health

Tobacco use is associated with numerous ocular diseases that result in vision loss. Smoking has been identified as the most important known preventable risk factor for developing age-related macular degeneration (AMD)16–19 and the strongest environmental risk factor for all forms of AMD.20 The more someone smokes, in terms of the number of cigarettes per day and years of smoking, the greater the likelihood of developing early AMD.21 The New York State Department of Health reports that non-smokers living with smokers have approximately double the risk of developing AMD.22 Cohort studies suggest that current smoking triples AMD incidence.23

Few countries have published data quantifying the number of people who have lost their vision as a result of smoking. A 2005 study in the UK estimated that 28,000 cases of AMD in older people is attributable to smoking.24 In Australia, it is estimated that 20% of all new cases of blindness in people over the age of 50 are caused by smoking.25 Further, exposure to second-hand smoke can also increase the risk of developing eye disease.

In 2014, the US Surgeon General report added AMD to the list of smoking-attributable diseases.19 The report’s executive summary describes the association between smoking and vision loss in a way that can be explained to patients. This is presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 US Surgeon General’s report concludes a causal relationship exists between cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) |

Epidemiological studies also indicate an association between smoking and an increased risk for age-related cataracts, particularly nuclear cataract,26,27 inflammatory and infectious uveitis,28 thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy,29,30 optic neuropathy,31,32 and ocular surface disorders.33,34

More recent studies have concluded that there is not sufficient evidence to attribute a causal association between smoking and incident primary open-angle glaucoma.31,35–36

It is in the best interest of patients to be advised by optometrists of the potentially harmful effects of smoking on their vision. The US Surgeon General further outlines how it is important for optometrists, ophthalmologists, and other health care providers to assess and address the smoking status of patients.19

Social marketing – communicating the causal association of smoking and ocular health

Globally, the public is largely unaware of the impact of smoking on eye health.37,38 In a 2011 study, few adult smokers from Canada (13.0%), the US (9.5%), and the UK (9.7%) were aware that smoking can cause blindness.37 However, in Australia, the federal government had for many years sponsored national awareness campaigns including a television commercial that linked smoking and blindness. In Australia, 47.2% of adult smokers were aware of this association – significantly higher than Canada, the US, and the UK, but the majority of smokers were still unaware of these links.

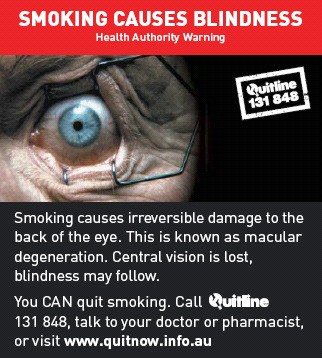

In recent years, the health effect from tobacco use on ocular health has been included by some countries’ health authorities on their tobacco product health warning labels (HWLs). Pictorial health warnings communicating smoking’s causal association with blindness has been used on cigarette packages in Australia, Canada, Singapore, Suriname, Iran, Jamaica, and New Zealand.39 Some examples of these warning labels are shown in Figures 1 and 2, which portray diseased eyes or eyes undergoing medical treatment.

| Figure 1 Australian health warning label, 2011. |

| Figure 2 Canadian health warning label, 2012. |

After the introduction of the blindness warning label on tobacco products (Figure 1), more than half of Australian smokers (62%) reported that they knew that smoking causes vision loss.40 The findings from this study suggest that even with comprehensive public education campaigns and the use of tobacco product HWLs, a substantial proportion of the population may still not know that their ocular health is at risk from smoking cigarettes. Further, when the Australian “Eye” HWL (Figure 1) was evaluated using focus groups, some participants, both smokers and non-smokers, suggested that the link between smoking and blindness was hard to believe. Some participants reported not understanding how smoking affects the eye and how visual loss can result; some believing that it must be caused from smoke getting in their eyes.41 There is therefore a need for eye care professionals to further educate their patients about how smoking impacts vascular health to ensure patients understand and believe that smoking can cause vision loss.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US has included the impact of smoking on vision loss in their “Tips from Former Smokers” campaign.42 One of the former smokers is a woman named Marlene who developed AMD from smoking. Her story is available from the CDC and available on the CDC channel on YouTube.43

Role for optometrists

There is compelling evidence that advice from health care practitioners is effective in encouraging smoking cessation and that a significant difference is made even with a minimal intervention with a patient – even an intervention that lasts less than 3 minutes in duration.44–46

Optometrists, as primary health care practitioners, could play a valuable role in educating patients about the health risks associated with smoking and promote smoking cessation. Every optometric appointment provides opportunity for optometrists to address the hazards of tobacco use, its impact on eye health, and the benefits of quitting.47

Optometrists are well positioned to address tobacco use with their patients. In Canada, for example, optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services.48 Studies to understand optometrists’ role in addressing tobacco use suggest that the vast majority of practitioners are not actively involved in tobacco-use prevention or cessation. One study found that many Canadian optometrists are uncomfortable addressing tobacco with patients because the optometrists surveyed believe that society already ‘‘hassles’’ people who smoke, and further rationalized that they are not the ‘‘best’’ suited primary care professional to support cessation.49

Optometrists are uniquely positioned to address tobacco use because smoking is a leading cause of vision loss. Many people fear losing their vision. In the US, a recent public opinion poll determined that many Americans describe losing eyesight as potentially having the greatest impact on their day-to-day life, more so than other conditions including loss of a limb, memory, hearing, and speech.50 In a British study, fear of blindness among youth was higher than the fear of heart disease, lung cancer, and stroke due to cigarette smoking.38,51 People recognize that vision loss would immediately compromise quality of life and independence since it leads to the inability to drive, read, travel in unfamiliar areas, and simply cope in everyday life.

Some optometrists have asked for pamphlets, posters, and other materials to help them initiate discussions with their patients about tobacco use. A variety of tools that help explain smoking and vision loss were developed in consultation with Canadian optometrists (Figures 3–6).

All materials are available for download and reproduction by visiting https://uwaterloo.ca/propel/resources-and-products/smoking-eye-health.

| Figure 3 Poster for optometry clinic – preparing patients to be asked about tobacco use. |

| Figure 4 Poster for optometry clinic – encouraging patients to ask optometrists about the health effects of smoking on ocular disease. |

| Figure 5 Poster for optometry clinic – explaining the causal association between smoking and vision loss. |

| Figure 6 Front and back covers of information pamphlet. |

Practitioners working in jurisdictions that have tobacco product HWLs can begin discussions with patients by asking if they have seen the new label.

Interventions that optometrists offer may increase the likelihood of tobacco users attempting to quit and being more successful when supported.44 There is strong evidence that advice from health care professionals in general can be effective in helping clients quit, and for many, cessation interventions are now considered requisite duties.44,52 A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and quasi-experiments concluded that patients who receive advice to quit smoking from “any health care provider” will result in increased quit rates.53 Furthermore, the role optometrists can play in assisting patients to quit smoking can have a major influence in their decision to take action toward quitting.

The WHO FCTC and the 2008 US Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline “Treating Tobacco-use and Dependence”, which reviewed 8,700 research articles, recommend that ALL health care professionals and students in health care education programs should be trained in effective tobacco-use cessation and dependence strategies.54,55

Numerous studies have identified that the optometry community does currently address some tobacco use among patients, and has an interest in doing more.49,56

How to talk to patients about tobacco use

Every primary care visit offers the potential to discuss such options, but communication can be difficult for patients and providers. Research has identified that patients expect health care providers to address smoking at every visit, that health care providers are trusted by patients, and the discussions need to be conducted with respect.57 Patients report that they prefer receiving messages that are positively framed, for example “when you quit…”, and “we have plenty of things for you to help [you quit]”.58

Many health care practitioners including dentists, pharmacists, nurses, midwives, occupational therapists, and others are providing patient advice or brief intervention regarding smoking cessation.52,58,59 Studies have shown that there is a positive response from various health care providers when providing some type of tobacco cessation intervention among patients.60,61 Many of these professions have developed and integrated tobacco cessation practices into their clinical practice guidelines, which reflect the importance of this issue in all aspects of health care.15,52,62

General approaches that can be used to support patient cessation

There are no official clinical guidelines for optometrists to follow to support tobacco use cessation; however, other primary care provider groups do have guidelines that could be adapted.

There are several approaches that optometrists and other health care practitioners may employ in order to assist patients in quitting smoking in a minimally intrusive manner. Some focus on connecting a patient with a specific cessation support service, while other approaches rely on the provider to personally support patient cessation.

When considering how to address tobacco use, there are some guiding principles that can support discussions with patients about tobacco use. These are listed below:

- To facilitate an appropriate response to tobacco use and dependence, it is necessary to recognize the addictive nature of tobacco.

- Effective management of tobacco use and dependence requires a coordinated interdisciplinary approach, including collaboration with the patient/client in order to provide patient-centered care.

- Recognize practice setting-specific needs and priorities.

- Recognize and respect cultural differences with respect to tobacco use.

- Frame the activities undertaken within a context of excellence in client care, patient safety, and integration.63

Practitioners need to remember that nicotine is a drug and discussions about tobacco use need to begin with understanding that smoking is generally not a “bad habit”, but a physical addiction. It is unlikely that any single health care provider will manage a patient’s addiction, and that patients will likely receive support from a range of providers including general practitioners, dentists, pharmacists, counselors, and hopefully optometrists. In Aboriginal North American communities, tobacco has an important cultural/spiritual role. It is important to recognize that commercial cigarettes are very different from traditional tobacco use but there is an important distinction. Some cultures commonly gift cigarettes and the use of cigarettes may be deeply incorporated into other activities.

A number of tobacco cessation counseling strategies exist and all are similar in terms of how health care providers can support patients. Perhaps two of the most known are the 5A program promoted by the United States Public Health Service64 and the ABC tool promoted by the New Zealand Smoking Cessation Guidelines Group. The ABC tool (Ask – all patients if they smoke; provide Brief advice to quit to all smokers; and offer Cessation support) was outlined in detail in a previous article for optometrists.65 There are online training resources for practitioners interested in being trained in the ABC method.66

This review article includes details of the 5A program, and each step is outlined in detail in Table 3.54,67–69 The 5As are Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, and Arrange. Each of these steps is detailed with suggestions on how to effectively communicate with patients.

| Table 3 The 5As model |

As stated above, optometrists should begin asking patients as young as age 9 about their tobacco use. The 5As does not include suggestions around scripting for prevention. Children and adolescents are knowledgeable about the fact that smoking is “bad” – but similar to adults, may be unaware that smoking can cause vision loss. Optometrists should focus prevention methods on the causal association of smoking and “blindness”, and relate impacts on quality of life such as lack of independence.

Recent qualitative research has highlighted that smokers do not need to be told that smoking is bad for their health;57 however, most adults who use tobacco may be unaware of the association between smoking and vision loss so that there is a need for eye health specialists to explain the causal association.

It is also important to remember that most people who smoke try to quit several times before they are successful. Cessation generally takes many attempts. Some people trying to quit will reduce the number of cigarettes smoked per day. In some studies, it is reported that most quit attempts (79%) last less than 1 day,70,71 the take home message being that quitting can be a complex process.

Discussion

Tobacco use is the most important, preventable risk factor for AMD, which is the leading cause of vision loss. The significant impact that vision loss has on the quality of life would undermine the overall health and well-being of all individuals. Based on this association between smoking and vision loss, it is clear that optometrists, as primary eye care providers, have good reason to address tobacco use among patients and are well positioned to advise patients on the issue.

Many optometrists, however, hold the belief that it is not their role to provide referrals to patients who require cessation assistance, and concede this to be the responsibility of primary care practitioners. Evidence suggests that advice from health care professionals can be effective in helping clients quit, and that optometrists can play a significant role in assisting patients to quit smoking and may influence their decision to take action toward quitting. Further, patients report that they expect their health care providers to discuss tobacco use at every visit and want support to quit.

Optometrists should provide educational materials to patients that explain how smoking is linked to vision loss. Educational tools such as posters and pamphlets are also available and can further support discussions. Optometrists should learn what cessation supports are available in their community. There may be community smoking cessation programs run through local public health agencies, cancer societies, or hospitals. Often countries/states/provinces provide telephone or web-based smoking cessation services that are often free of charge for patients.

Optometrists have also expressed a strong interest in pursuing further training through continuing education programs that focus on the impact of smoking on vision and eye health;52 as well as a program that focusses on how to provide smoking prevention and cessation advice to patients. Such programs have been delivered in Canada through the University of Waterloo School of Optometry and Vision Science.72 In the UK, a pilot study has demonstrated the feasibility of delivering brief smoking cessations with good success.73

Specific actions optometrists can take to support tobacco-use prevention and cessation are highlighted in Table 4.

| Table 4 Actions optometrists can take to support tobacco-use prevention and cessation |

With the proper training and resources, it is certain that optometrists can and will play a greater role in addressing tobacco-use cessation among patients, and have a deep influence in a patient’s potential success in quitting. There is still significant work to have optometry fully integrated into the tobacco-use prevention and cessation systems, but this will develop with deep co-operation between public health and optometry partners. Optometrists’ potential contributions are too great to not be fully engaged.

Acknowledgments

Ryan David Kennedy completed this work through support from the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact at the University of Waterloo. The Propel Centre for Population Health Impact was supported by a Major Program grant from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Initiative (CCSRI grant number 701019).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Eriksen MP, Mackay J, Schluger N, Islami F, Drope J. The Tobacco Atlas 2015. 5th ed. American Cancer Society; 2015. | |

World Health Organization. Tobacco free initiative: why tobacco is a public health priority [updated 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/health_priority/en/. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. The Lancet 2011;377:139–146. | |

World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Line HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e20. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Office of smoking and health. Tobacco use: targeting the nation’s leading killer. At a glance 2011. Available from: http://198.246.124.29/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/pdf/2011/tobacco_aag_2011_508.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Jha P, Phil D, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:60–68. | |

Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:655–664. | |

Reid JL, Hammond D, Rynard VL, Burkhalter R. Tobacco Use in Canada: Patterns and Trends. 2014 Edition. Waterloo, ON: Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo. Available from: http://www.mantrainc.ca/assets/tobaccouseincanada_2014.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Fong GT, Hammond D, Laux FL, et al. The near-universal experience of regret among smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S341–S351. | |

World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [updated 2015; cited May 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/en/. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, Borland R, Cummings KM. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl III):19–25. | |

Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions to prevent tobacco use in children and adolescents: U S Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:552Y7. | |

Patnode CD, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, Perdue LA, SohC, Hollis J. Primary care-relevant interventions for tobacco use prevention and cessation in children and adolescents: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:253Y60. | |

Borland R, Li L, Driezen P, Wilson N, et al. Cessation assistance reported by smokers in 15 countries participating in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) policy evaluation surveys. Addiction. 2012;107(1):197–205. | |

Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, et al. Smoking and age related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(1):75–80. | |

Chakravarthy U, Wong TY, Fletcher A, et al. Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;13:31. | |

Thornton J, Edwards R, Mitchell P, Harrison RA, Buchan I, Kelly SP. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association. Eye. 2005;19:935–944. | |

The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Printed with corrections, Jan 2014. Available from: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Seddon JM, Ferris FL; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Risk factors for the incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease study (AREDS). Ophthalmology. 2005;112:533–539. | |

Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Nash SD, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and associated risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;128(6):750–758. | |

New York State Department of Health. Albany: Smoking can lead to vision loss of Blindness [updated December 2009; cited May 2015]. Available from: http://www.health.ny.gov/prevention/tobacco_control/smoking_can_lead_to_vision_loss_or_blindness.htm. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Neuner B, Komm A, Wellmann J, et al. Smoking history and the incidence of age-related macular degeneration – results from the Muenster Aging and Retina Study (MARS) cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis of observational longitudinal studies. Addict Behav. 2009;34(11):938–947. | |

Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RP. 28,000 Cases of age related macular degeneration causing visual loss in people aged 75 years and above in the United Kingdom may be attributable to smoking. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(5):550–553. | |

Mitchell P, Chapman S, Smith W. Smoking is a major cause of blindness. Med J Aust. 1999;171:173–174. | |

Ye J, He J, Wang C, et al. Smoking and risk of age-related cataract: a meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):3885. | |

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. | |

Lin P, Loh AR, Margolis TP, Acharya NR. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):585–590. | |

Thornton J, Kelly SP, Harrison RA, Edwards R. Cigarette smoking and thyroid eye disease: a systematic review. Eye. 2007;21:1135–1145. | |

Vestergard P. Smoking and thyroid disorders – a meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:153–161. | |

Cheng ACK, Pang CP, Leung ATS, Chua JKH, Fan DSP, Lam DSC. The association between cigarette smoking and ocular diseases. Hong Kong Med J. 2000;6: 195–202. | |

Chung SM, Gay CA, McCrary JA. Nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy. The impact of tobacco use. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:781–783. | |

Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, Goto E, et al. Alterations of the tear film and ocular surface health in chronic smokers. Eye. 2008;22:961–968. | |

Rummenie VT, Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, et al. Tear cytokine and ocular surface alterations following brief passive cigarette smoke exposure. Cytokine. 2008;43(2):200–208. | |

Edwards R, Thornton J, Ajit R, Harrison RA, Kelly SP. Cigarette smoking and primary open angle glaucoma: a systematic review. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(7):558–566. | |

Kang JH, Pasquale LR, Rosner BA, et al. Prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(12):1762–1768. | |

Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Parkinson CM, Fong GT. Knowledge about the relationship between smoking and blindness in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia: results from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Project. Optometry J Am Optometr Assoc. 2011;82(5):310–317. | |

Thornton J, Edwards R, Harrison RA, Elton P, Astbury N, Kelly SP. ‘Smoke gets in your eyes’: a research-informed professional education and advocacy programme. J Public Health. 2007;29(2):142–146. | |

Tobacco Labelling Resource Centre. Available from: http://www.TobaccoLabels.ca. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Behm I, Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R. Positive impact of Australian ‘blindness’ tobacco warning labels: findings from the ITC four country survey. Clin ExpOptom. 2012;95(6):590–598. | |

Shanahan P, Elliott D. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Graphic Health Warnings on Tobacco Product Packaging 2008; 2009. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips from Former Smokers – Marlene’s Story. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/stories/marlene-biography.html. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC: Tips From Former Smokers – Marlene’s Eye Injections. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jJUtRAPix0. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000165. | |

Carr A, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005084. | |

Sinclair HK, Bond CM, Stead LF. Community pharmacy personnel interventions for smoking cessation. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD003698. | |

Optometrists Association Australia. Position Statement: Tobacco Smoking; July 2010. Available from: http://www.optometry.org.au/media/278147/position_statement_tobacco_smoking.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

American Optometric Association. Optometric Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Available from: http://www.aoa.org/optometrists/tools-and-resources/evidence-based-optometry/evidence-based-clinical-practice-guidlines?sso<y. Accessed March 3, 2015. | |

Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Schultz AS, Iley MD, Zawada V. Smoking cessation referrals in optometric practice: a Canadian pilot study. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:766–771. | |

National Alliance for Eye and Vision Research; Research to Prevent Blindness. Media Release (September 18, 2014): New Public Opinion Poll Reveals a Significant Number of Americans Rate Losing Eyesight as Having Greatest Impact on their Lives Compared to Other Conditions. Available from: http://www.eyeresearch.org/pdf/Poll_press_release.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015. | |

Moradi P, Thornton J, Edwards R, Harrison RA, Washington SJ, Kelly SP. Teenagers’ perceptions of blindness related to smoking: a novel message to a vulnerable group. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(5):605–607. | |

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, Canadian Association of Social Workers, Canadian Dental Association, Canadian Medical Association, Canadian Nurses Association, Canadian Pharmacists Association, Canadian Physiotherapy Association, Canadian Psychological Association, and Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists. Tobacco: the role of health professionals in smoking cessation. Joint Statement. J Can Dental Assoc. 2001;67(3):134–135. | |

Gorin SS, Heck JE. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of tobacco counseling by health care providers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:2012–2022. | |

Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; May 2008. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015. | |

Tobacco Free Initiative: Policy recommendations for smoking cessation and treatment of tobacco dependence. World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/resources/publications/tobacco_dependence/en/. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Douglas O, et al. Patient tobacco use in optometric practice: a Canada-wide study. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91(7):769–777. | |

Halladay JR, Vu M, Ripley-Moffitt C, Gupta SK, O’Meara C, Goldstein AO. Patient perspectives on tobacco use treatment in primary care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E14. | |

Abatemarco DJ, Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD. Midwives’ knowledge, perceptions, beliefs, and practice supports regarding tobacco dependence treatment. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2007;52:451–457. | |

Walsh SE, Singleton JA, Worth CT, et al. Tobacco cessation counseling training with standardized patients. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(9):1171–1178. | |

Gordon JS, Andrews JA, Albert DA, Crews KM, Payne TJ, Severson HH. Tobacco cessation via public dental clinics: results of a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1307–1312. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.181214. | |

Hall S, Reid E, Ukoumunne OC, Weinman J, Marteau TM. Brief smoking cessation advice from practice nurses during routine cervical smear tests appointments: a cluster randomised controlled trial assessing feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1057–1061. | |

Sandhu HS. A practical guide to tobacco cessation in dental offices. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:153–157. | |

Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. Management of Tobacco Use and Dependence – Regional Clinical Practice Guidelines – Evidence Informed Practice Tools. Winnipeg Regional Health Authority; 2013. | |

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2nd Ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. | |

Sheck LH, Field AP, McRobbie H, Wilson GA. Helping patients to quit smoking in the busy optometric practice. Clin ExpOptom. 2009;92:75–77. | |

LearnOnline – Learning resources for health practitioners. Ministry of Health. Available from: http://learnonline.health.nz/login/index.php. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Hoppe E, Frankel R. Optometrists as key providers in the prevention and early detection of malignancies. Optometry. 2006;77:397–404. | |

Zwar NA, Richmond RL, Forlonge G, Hasan I. Feasibility and effectiveness of nurse-delivered smoking cessation counselling combined with nicotine replacement in Australian general practice. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(6):583–588. | |

Hoppe E. A model curriculum for teaching optometry students about smoking cessation education. Optometric Educ. 1998;24(1):21–26. | |

Hughes JR, Solomon L, Naud S, Fingar JR, Helzer JE, Callas PW. Natural history of attempts to stop smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(9):1190–1198. | |

Berg CJ, An LC, Kirch M, et al. Failure to report attempts to quit smoking. Addict Behav. 2010;35:900–904. | |

Optometry & Vision Science. University of Waterloo. Available from: https://uwaterloo.ca/optometry-vision-science/. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

Lawrenson JG, Roberts CA, Offord L. A pilot study of the feasibility of delivering a brief smoking cessation intervention in community optometric practice. Public Health. 2015;129(2):149–151. | |

Tobacco Labelling Resource Centre. Available from: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/. Accessed August 13, 2015. | |

University of Waterloo. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. Your optometrist will ask you poster – English; 2012. Available at: https://uwaterloo.ca/propel/sites/ca.propel/files/uploads/files/YourOptometristWillAskYouPoster_en.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2015. | |

University of Waterloo. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. Feel free to ask (your optometrist) poster – English; 2012. Available at: https://uwaterloo.ca/propel/sites/ca.propel/files/uploads/files/FeelFreeToAskPoster_en.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2015. | |

University of Waterloo. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. How does smoking cause blindness? [poster]; 2012. Available at: https://uwaterloo.ca/propel/sites/ca.propel/files/uploads/files/HowSmokingCausesBlindnessPoster_en.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2015. | |

University of Waterloo. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. Smoking and your eye health brochure – English; 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/PropelEyeHealth. Accessed October 6, 2015. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.