Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 14

Spontaneous perirenal urinoma induced by NSAID-associated acute interstitial nephritis

Authors Chang H, Kuei C , Tseng C, Hou Y, Tseng Y

Received 3 November 2017

Accepted for publication 8 January 2018

Published 23 March 2018 Volume 2018:14 Pages 595—599

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S155978

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Deyun Wang

Hsiu-Wen Chang,1 Chia-Hao Kuei,2 Chin-Feng Tseng,1 Yi-Chou Hou,3 Ying-Lan Tseng1

1Department of Internal Medicine, Cardinal Tien Hospital, School of Medicine, Fu-Jen Catholic University, Xin-dian District, New Taipei City, Taiwan, Republic of China; 2Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Cardinal Tien Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan, Republic of China; 3Department of Internal Medicine, Cardinal Tien Hospital An-Kang Branch, School of Medicine, Fu-Jen Catholic University, Xin-dian District, New Taipei City, Taiwan, Republic of China

Abstract: Urinoma, defined as the urine leakage beyond the urinary tract, is commonly induced by blunt trauma or urinary tract obstruction by stone, intra-abdominal malignancy, or retroperitoneal fibrosis. Spontaneous urinoma is rare and parenchymal pathologic change is rarely mentioned when urinoma is found. We present a case of a 28-year-old woman with bilateral flank pain induced by spontaneous urinoma. The lady received chronic analgesics because of migraine. After intravenous ketorolac injection, bilateral perirenal urinoma developed. Renal biopsy showed acute interstitial nephritis associated with nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). After discontinuing the medication, urinoma subsided, and the patient was discharged with normal serum creatinine. This was the first case of urinoma induced by NSAID-related interstitial nephritis, and pathophysiology and management of spontaneous urinoma are discussed.

Keywords: spontaneous urinoma, NSAID, interstitial nephritis, acute kidney injury, ketorolac

Introduction

Urinoma is an encapsulated collection of leaked urine outside the urinary tract. It is commonly caused by blunt trauma or urinary tract obstruction by a stone, intra-abdominal malignancy, or retroperitoneal fibrosis.1 Spontaneous urinoma, on the other hand, is rare and is detected only when flank pain has developed. Acute interstitial nephritis is a rarely reported etiology of spontaneous urinoma, and there is still no consensus on the management of spontaneous urinoma.2 We present the case of a 28-year-old woman with spontaneous urinoma due to nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated acute interstitial nephritis.

Case report

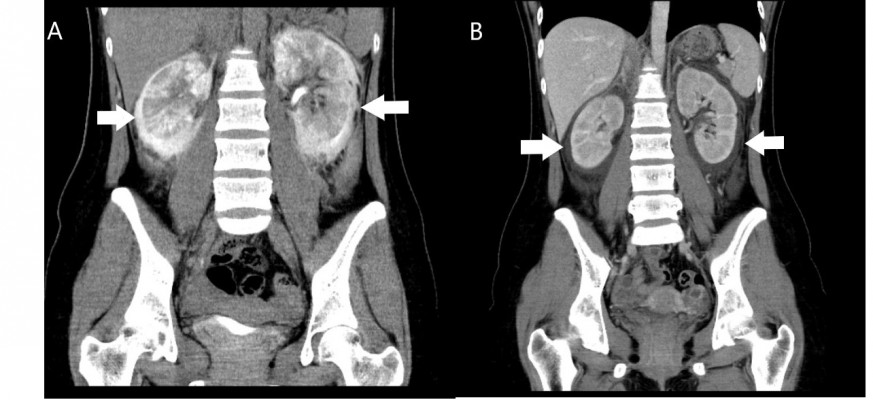

The patient was a 28-year-old Taiwanese woman who had a history of migraine with regular intake of analgesics (diclofenac 25 mg or mefenamic acid 500 mg twice or thrice per day), but no previous hospitalization in recent years. After a Christmas feast, she experienced periodic headache and epigastric discomfort, so she took the analgesic agent as usual; however, no relief was obtained. Therefore, she visited our emergency department on December 27, 2016. The renal function at presentation was within normal limits (blood urea nitrogen: 9 mg/dL; serum creatinine: 0.66 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]: 113.3 mL/min). Ketorolac (30 mg intravenously) was given in the emergency department, which gave the patient significant relief, following which she was discharged. Two days later (December 29, 2016), she suddenly developed bilateral flank pain and mild dysuria. She visited the family medicine clinic. Urinalysis revealed proteinuria (3+), but only 0–2 red blood cells per high-power field (HPF), 3–5 white blood cells (WBCs)/HPF, and no casts. She was referred to our nephrology outpatient department. Blood examination revealed an acute decline in renal function (serum creatinine: 1.25 mg/dL, eGFR 54.2 mL/min) and relative leukocytosis (WBCs: 9840/ mm3; 81% neutrophils, 10.9% lymphocytes, and 0.2% eosinophils). Her hemoglobin level was 15.6 g/dL (normal range, 12–16 g/dL); C-reactive protein, 1.436 mg/dL; and blood urea nitrogen, 22 mg/L. No fever was noted. Because of acute deterioration of kidney function with gross proteinuria and persistent bilateral flank pain, she was admitted for further evaluation and management to the nephrology ward. On admission, no impaired consciousness was observed, and her body mass index was 19. Arterial pressure was 133/73 mmHg, heart rate was 63 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 22 breaths/min. Physical examination revealed bilateral costovertebral angle tenderness with mild, pitting lower-leg edema. After admission, spot-urine urinary protein/creatinine ratio was 3.707.95 mg/g. Serum albumin level was 4.53 g/dL. Serologic test results included normal levels of complement, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, anti-dsDNA, and basement membrane antibody. Serum immunoglobulins levels were within normal limits. Hepatitis B and C test results were negative. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed mild right pyelectasis. However, progressive renal dysfunction with increased serum creatinine (2.37 mg/dL) and oliguria was noted on December 30. The summary of laboratory result is listed in Table 1. Therefore, hemodialysis and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1) were performed on that same day. The delayed phase image (Figure 1A) shows the intravenous contrast media in the perirenal area without filling defects. The excretory phase image reveals (Figure 1B) fluid retention in the perirenal area without enhancement. These radiologic findings indicated urinoma in the bilateral perirenal area, that is, perirenal urinoma. No evidence of external compression was found. A Foley catheter and bilateral double-J ureteral stent were inserted to decrease bladder pressure.

The patient continued to have progressive renal dysfunction and oliguria. Kidney biopsy was performed on January 2, 2017, and histopathologic examination (Figure 2) revealed mononuclear cell infiltration and eosinophils in the renal parenchyma with glomerular sparing. Thus, acute interstitial nephritis was diagnosed. NSAID was discontinued, and symptoms then resolved completely. Her serum creatinine had dropped to 0.67 mg/dL on January 5. She was discharged 2 days later. One month after discharge, both the Foley catheter and double-J ureteral stent were removed. At the follow-up visit on January 9, flank pain had not recurred.

| Figure 2 Histopathologic examination of the kidney revealed interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration (arrow head) with glomerular sparing (arrow). |

Discussion

We report the first case of spontaneous urinoma induced by NSAID-associated acute interstitial nephritis. Urinoma is typically found in the perirenal area.1 It is mostly induced by traumatic breach of the integrity of the renal pelvis, calices, or ureter. Subcapsular fluid collection as a presentation of renal parenchymal disease without obstructive lesions is rare. Focal segmental glomerulonephritis is the common histopathologic change in the literature.3–5 In our patient, acute interstitial nephritis due to NSAID was the etiology of the acute kidney injury and consequent subcapsular fluid accumulation.4 This is the first reported case of acute interstitial nephritis presenting as perirenal fluid accumulation. Perirenal fluid is a spontaneous subcapsular transudate in patients suffering from nephropathy and in a sodium retention state, with or without renal failure.6 Subcapsular fluid collection may be noticed incidentally on imaging as a crescent-shaped collection. Distension of the renal capsule and Gerota’s fascia may result in local pain. Diagnosis is made using ultrasonography or CT, which shows unilateral or bilateral fluid accumulation.3 Although the mechanism underlying spontaneous urinoma remains unknown, poor lymphatic drainage because of chronic analgesic use may have been the main cause in our patient. Exudative fluid and cellular infiltration into the interstitium are the hallmark of interstitial nephritis.7 In glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome, urinoma occurs because of lymphangiectasia.3 Studies have shown that lymphangiectasis is the main coexisting factor for spontaneous urinoma, indicating that lymphatic vessels are crucial for the prevention of fluid accumulation.3 In inflammatory disease, lymphatic vessels are important for edema clearance. When lymphatic vascular development is hindered, the tissue edema cannot be relieved and fluid accumulation occurs in a perirenal area.8 Inflammatory cytokines are critical for lymphatic vessel development. Lyons et al noted that cyclooxygenase 2 improved lymphatic vessel development in breast cancers.9 The application of aspirin also decreased sarcoma development by inhibiting angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis.10 Our patient took analgesics regularly to alleviate her migraine. Based on the evidences from abovementioned animal studies, long-term use of analgesics may affect the microstructure of the lymphatic vessels. However, our patient’s flank pain occurred after intravenous ketorolac injection, which is well known to induce interstitial nephritis.11 Intravenous ketorolac is highly associated with acute kidney injury, and minimal change disease with negative immunofluorescence or interstitial nephritis are the possible pathologic findings.12,13 Following intravenous ketorolac, the acute interstitial inflammation induced exudate accumulation. Although no lymphatic imaging was performed for our patient, long-term use of an NSAID and exacerbated allergic reaction by ketorolac in renal tissue were probably the contributing factors to urinoma occurrence.

Treatment of subcapsular effusion in nephrotic syndrome is achieved best by treating the underlying kidney disease and draining the subcapsular fluid if necessary.4 Simple aspiration of the fluid if the accumulation is moderate and control of the underlying glomerulopathy may suffice. There are three grades of perirenal fluid on ultrasonography: grade 1, a thin layer of perirenal fluid; grade 2, a moderate amount of collected perirenal fluid with indentations of the renal parenchyma and strands in the fluid; and grade 3, a large fluid collection surrounding the kidney.6 Our patient had grade 2 fluid accumulation. Severity of flank pain may not correlate with the amount of fluid accumulation in nephrotic syndrome. Therefore, in patients with glomerulonephritis and flank pain, subcapsular fluid accumulation should be considered. In contrast to posttraumatic subcapsular urinoma, there is still no consensus on the role of surgical drainage for spontaneous urinoma, unless the amount of fluid compresses the surrounding kidney or complications such as infection or hemorrhage occur. In most instances, small urinomas will reabsorb spontaneously, and drainage is not necessary. Different treatment protocols to correct the underlying cause are outlined, such as drainage by percutaneous nephrostomy or placement of a stent across a ureteral defect to promote drainage of urine from the kidney into the bladder as well as drainage of the urinoma using appropriately positioned catheters.14 Our patient received a transient double-J catheter, and there were no clinical events. If the entire amount of fluid cannot be drained, treating the underlying disease without percutaneous drainage may be an alternative for regression of the subcapsular fluid accumulation.

In summary, spontaneous perirenal urinoma is a rare etiology for flank pain, and acute interstitial nephritis coexisting with lymphangiectasia is a contributing factor. In contrast to the treatment for traumatic urinoma, conservative treatment without percutaneous drainage should be the first-line management.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the Conference Taiwan Urology Association 2017 Annual Meeting as a poster presentation/conference talk with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in TUA 2017 Annual Meeting Book (http://eschool.tua.org.tw/media/5070). Written informed consent was provided by the patient to have the case details and accompanying images published.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Morano JU, Burkhalter JL. Percutaneous catheter drainage of post-traumatic urinoma. J Urol. 1985;134(2):319–321. | ||

Ketabchi AA, Ketabchi M, Barkam M. Percutaneous drainage of a late-onset giant posttraumatic urinoma. Urol J. 2009;6(3):214–216. | ||

Wani NA, Mir F, Gojwari T, Qureshi UA, Ahmad R. Subcapsular fluid collection: an unusual manifestation of nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(1):181–184. | ||

Yalcin AU, Akcar N, Can C, Kasapoglu E, Sahin G. An unusual presentation for nephrotic syndrome. Bilateral perirenal subcapsular fluid collection. Nephron. 2002;92(1):244–245. | ||

Yilmaz S, Zor M, Ersan M, Hamcan S. Bilateral massive perirenal subcapsular effusion: a case report. J Clin Ultrasound. 2017;45(9):597–599. | ||

Haddad MC, Medawar WA, Hawary MM, Khoury NJ, Ammouri NF, Shabb NS. Perirenal fluid in renal parenchymal medical disease (“floating kidney”): clinical significance and sonographic grading. Clin Radiol. 2001;56(12):979–983. | ||

Rastegar A, Kashgarian M. The clinical spectrum of tubulointerstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54(2):313–327. | ||

Seeger H, Bonani M, Segerer S. The role of lymphatics in renal inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(7):2634–2641. | ||

Lyons TR, Borges VF, Betts CB, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent lymphangiogenesis promotes nodal metastasis of postpartum breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(9):3901–3912. | ||

Zhang X, Wang Z, Wang Z, et al. Impact of acetylsalicylic acid on tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis through inhibition of VEGF signaling in a murine sarcoma model. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(5):1907–1913. | ||

Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, et al. Association of individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and chronic kidney disease: a Population-Based Case Control Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122899. | ||

Mariano F, Cogno C, Giaretta F, et al. Urinary protein profiles in ketorolac-associated acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopedic day surgery. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:269–274. | ||

Haragsim L, Dalal R, Bagga H, Bastani B. Ketorolac-induced acute renal failure and hyperkalemia: report of three cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24(4):578–580. | ||

Lang EK, Glorioso L 3rd. Management of urinomas by percutaneous drainage procedures. Radiol Clin North Am. 1986;24(4):551–559. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.