Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Shame: Does It Fit in the Workplace? Examining Supervisor Negative Feedback Effect on Task Performance

Authors Zada S, Khan J , Saeed I, Wu H, Zhang Y, Mohamed A

Received 12 April 2022

Accepted for publication 28 June 2022

Published 6 September 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 2461—2475

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S370043

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Shagufta Zada,1,2 Jawad Khan,3 Imran Saeed,4 Huifang Wu,1 Yongjun Zhang,1 Abdullah Mohamed5

1Business School, Henan University, Kaifeng, 475000, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences Ilma University Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan; 3Department of Business Administration, Iqra National University, Peshawar, Pakistan; 4IBMS, the University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan; 5Research Centre, Future University in Egypt, New Cairo, 11835, Egypt

Correspondence: Huifang Wu, Business School, Henan University, Kaifeng, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: One of the most exciting aspects of organisational psychology is the study of shame and the factors that lead up to it. The purpose of this study was to examine the relation between supervisor negative feedback and task performance. Further, we examined the mediating role of shame between supervisor negative feedback and task performance and the moderating role of self-esteem.

Methods: Employees working full-time in educational institutions across Pakistan were selected to collect data from the respondents. By using a convenience sampling technique, 258 employees participated in the study. The data were collected in three phases to reduce the problem of the common variance bias. Direct paths were tested by using simple linear regression (SPSS V.25). Hayes (2017) PROCESS macro model 4 was used for mediation and model 1 for moderation.

Results: The findings revealed that negative feedback from supervisors is linked positively with employees’ task performance. Further, shame partially mediates the relation between supervisor negative feedback and tas performance. When self-esteem is high, negative feedback and task performance were more strongly associated than low.

Discussion: This study has theoretical and practical implications and is based on the well-known theory of psychology ie affective events theory (AET), which states that workplace events cause emotions, influencing work attitudes and actions. This study fills the gap which is unknown to the scholars and practitioners in understanding that supervisor negative feedback is helpful to enhance employee task performance via feeling shame.

Keywords: shame, supervisor negative feedback, self-esteem, task performance

Introduction

“Where there is a shame, there is a virtue”.

Xing, Sun1 stated that the most apparent factor in organisational psychology research is an overemphasis on mood at the workplace. Since then, researchers have started to adopt a more realistic perspective to study emotions in corporate life. The affective events theory (AET),2 attempts to explain how feelings and moods impact one’s performance at work as well as their level of job satisfaction. The idea explains the connection between the internal factors, such as personality, emotions, and cognition, of workers and their responses to situations that take place while they are on the job. Concentrating on the function of a wide range of distinct emotions rather than a single generalised emotion, such as fear,3 anger,4 and happiness.5 Distinct emotions in interpersonal interactions have received considerable attention.6,7 Shame is a relevant but understudied emotion that deserves more attention.1 Understanding organisational shame is essential for several reasons. Organisational settings provide fertile grounds for the formation and maintenance of our identities. They offer us an environment for interaction and developing attributes relevant to our job and profession.8 Diversity in our relationships, events and processes that occur throughout a typical workday can draw attention to the shortfall of these identities and provoke feelings of shame as a consequence.9 It is possible to feel embarrassed at work due to daily events, such as performance evaluations, supervisor behavior, shifting in hierarchical structures, and motivating and rewarding systems.1 Shame may be elicited unintentionally. However, it can also be produced consciously through particular interactions and actions (Mayer, 2020). Other than personal shortcomings, shame may be experienced due to mistakes made by one’s coworkers, teams, or even the company itself.10

In organisational settings, shame is defined as “a painful emotion that arises when an employee evaluates a threat to the self when he/she has fallen off an important standard tied to a work-related identity”.11 Identity theories explain that people’s self-worth may be estimated more accurately with the help of others’ judgments and feedback, and these evaluations and feedback are directly associated with their feeling of self-esteem (Cortina et al, 2021). It is possible to understand how shame is generated by providing negative feedback, which signals a gap between employee conduct and company norms. Conscious supervisor conduct plays an essential role in determining an individual’s identity.12 Negative feedback from supervisors is effective in instilling feelings of shame in employees.

In comparison, little empirical research has been conducted on this link, which has resulted in a limited understanding of how shame is formed in supervisor-subordinate relationships.13 The unique motivating aspect of shame is essential to consider the repercussions of feeling ashamed. Compared to other negative emotions, like irritation and anger, shame is caused by employee’s internal danger to one’s self-worth and performance.14,15 Research typically implies that people handle shame by removing themselves from the circumstances that are causing them to feel ashamed.12 Self-protection from being ashamed in organisational contexts is related to psychological and physical engagement in the workplace, such as a desire to work in a team, share knowledge, and increase performance.16 However, new studies have shown that people’s reactions to shame are more diverse than previously assumed.17 In addition to the self-protective retreat of self-esteem, shame may prompt people to repair and restore their endangered identity by re-attempting the activity and making apologies, leading to more productive work habits.18 The concept is that repair motivation is initially triggered, followed by protection. Shame’s repercussions have generally been overlooked in organisational studies because of the lack of attention paid to this repair incentive (ie, self-esteem).1 The importance and understanding of shame in all organizations have high value, such as other emotions. Shame has the unique ability to inspire fundamental changes in oneself.19 This has significant consequences for both shamed employees and their organisations. Research has revealed that shame can lead to productive, withdrawn, or hostile actions.20 This massive range of shame reactions stresses the essential to investigate what situational drive to convert harmful reactions of shame toward more positive and valuable reactions. A more recent study shows findings shows that supervisor developmental feedback is more positively associated with employee creativity.21 Other relevant studies indicate that supervisor positive feedback has a positive effect on promotion focus and employee performance.22 Most of the prior studies are focusing on the positive feedback of the supervisor and its associated outcomes but negative feedback from the supervisor and its associated outcomes are still under investigation.23 The prior literature focuses that there is a dire need to investigate this relationship. Previous literature has highlighted work-related outcomes and the role of shame as a predictor, and its effect on task performance.24

This study aims to establish and analyse shame’s antecedents and consequences to fill gaps in the literature about how shame affects individuals after receiving negative feedback from a supervisor. Using the paradigm of workplace shame, we examined whether such feelings of shame predicted the attitudes and behaviours of workers. The repair motivator (ie, self-esteem) has been suggested to motivate workers to improve their performance in retaining their self-image. This conceptual and theoretical argument inserts two major contributions to the body of knowledge. First, it contributes to the literature by examining the effects of supervisors’ negative feedback on an employee’s task performance. Attaining negative feedback from the supervisor is very important as it will help to correct our development and recognize critical adjustments necessary in the workplace. Feedbacks are valuable because it allows us to monitor our performance and alerts us to significant changes we need to make. Negative feedback is considered to negatively affect employee performance due to employee ego and self-esteem.10 Still, a positive relationship with employee performance needs further examination, and in this study, shame plays an underlying mechanism. Rather than just causing a self-protective retreat, shame may also motivate people to seek to repair and restore their endangered selves via retrying the activity and making apologies. Second, we investigated self-esteem as a buffering mechanism to further examine the role of negative feedback in employees’ task performance in a supervisor-subordinate context. It’s not only the supervisor’s position that determines how an employee reacts to unfavourable criticism. It’s important to remember that people are not just passive consumers of feedback; they are also actively involved in understanding and managing it. Many studies have examined the importance of individual characteristics in determining how people respond to feedback. Many studies show that people’s reactions to negative feedback are influenced by their level of self-esteem (SE). Consequently, we may predict that the degree to which individuals react to negative feedback in an attempt to improve their performance will be affected by the presence of SE. Specifically, we investigated the role of the repair motive (ie, self-esteem) after experiencing shame in terms of task performance to clarify the significance of supervisory negative feedback effects1,10 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Conceptual framework. |

Literature Review

Supervisor Negative Feedback and Task Performance

Getting feedback from upper-level management is far more common than getting it directly from peers.25 Supervisors are expected to have in-depth knowledge of their subordinates’ performance areas and aware of performance criteria. Consequently, their contributions and input are seen as credible and relevant in employees’ task performance.26,27 Supervisors offer feedback to employees to help and encourage them to improve their performance to get maximum results.28 Performance management is a complex process that requires constant feedback.29 2019). Employees benefit from their supervisors’ feedback since it serves as a tool for their growth and development. Supervisory feedback plays a significant role in achieving organisational goals and is also important for employees’ survival.30 The previous research examined the link between feedback and improvements in managerial performance by analysing how it influences the organisation’s learning and motivation processes.31 Feedback is defined as “a special case of the general communication process in which a sender conveys a message to a recipient that comprises information about the recipient’s behaviour and performance”.32 Feedback is received by receivers, who then evaluate their work performance in light of the feedback. It may come from various sources, including external sources (such as input from supervisors, subordinates, coworkers, and customers who watch and provide feedback) and the task environment.33 Ashford and Tsui34 found that employees were more willing to seek feedback from supervisors, showing that supervisor input is more highly valued. Following research conducted by Ashford (1993) indicated that workers who received more attention and credibility from their supervisors were more likely to attain their goals. Employees in the organisation rely on and pay attention to supervisor input for various reasons, including improving their performance and advancing their careers.

The question of how to enhance employee performance is one of the phenomena that many academics and practitioners are interested in examining.31,35 When employees get negative feedback, their overall performance improves as a result of the fact that it allows them to advance in their careers. The assumption that workers who have gotten positive performance-based feedback believe that their input is accurate and satisfied is reasonable.32,35 However, Podsakoff and Farh36 found that people are more motivated to improve their performance when given negative feedback than when given good feedback. This is especially true when employees set higher and more difficult performance goals. According to Ilgen, Fisher32 and Podsakoff and Farh,36 the nature of the feedback was based on performance and outcome evaluations, respectively. Nease, Mudgett37 stated that positive and negative feedback has a variety of consequences on employee emotions and behavior. Some people get bad feedback and thus increase their efforts to accomplish their work objectives (to protect resources), while others lower their efforts to achieve their work goals.

H1. There is a positive and significant relationship between supervisor negative feedback and task performance.

Supervisor Negative Feedback and Employees’ Shame

Employees who get negative feedback are more likely to detect and evaluate that their performance falls under organisational standards. In research in which individuals were asked to explain shame-inducing incidents, failure to perform was the most often mentioned answer Keltner.38 According to Hillebrandt and Barclay,10 two processes occur when self-identity is endangered, and shame is elicited: 1) a divergence from identity-related criteria, and credit for this deviation is given to self. Negative supervisor feedback would evoke feelings of shame in workers via these two procedures on a person-to-person basis.39,40 First, supervisor negative feedback may signal a negative divergence from standards associated with the workers’ professional identities, according to certain concepts. The performance of specified duties by employees within a profession or vocation is anticipated to be sufficient, following the standards and expectations of their employer.18

Additionally, individuals will commit themselves to these professional responsibilities and absorb them into their standards as a result.41 In an organization job identity as compared to other identity as more salient for subordinate due to its better exceptionality and concreteness than different identities.42 Negative feedback indicates a failure to pursue objectives or a deviation from the right or typical activities in the performance. It reflects a failure to achieve the criteria that underpin job identity and performance requirements. In this way, repeated negative feedback from supervisors is likely to increase an employee’s belief that they have departed from ideal norms, resulting in feelings of embarrassment at the place of employment.43 Second, employees who get negative feedback from their managers are more prone to place the responsibility for their poor performance on their shoulders. A convincing social process may be provided to individuals via work-related feedback, which educates them of their abilities and capabilities.44 Negative feedback indicates a lack of capacity and implies that workers’ performance is lacking; employees may interpret the gap between the organization’s objectives and their performance as evidence of a problem with their own identity.14 The probability that an individual may experience feelings of shame at work grows in direct proportion to the number of times they get negative feedback on a given day. According to empirical research, negative feedback may provoke unpleasant emotions in employees, including feelings of guilt and shame.18,45,46

H2. There is a positive and significant association between supervisor negative feedback and employees’ shame in the workplace.

Shame and Task Performance

Employees who get negative feedback from supervisors may feel embarrassed and driven to put things right. Sentiments of shame drive employees to engage in self-development and societal betterment activities at their places of employment.18,47 The immediate outcome of these inclinations is improved work performance.48 The feelings of shame that employees experience lead to compensatory behaviours intended to restore their self-esteem, which leads to improved task performance. Someone who is experiencing shame becomes aware that their self-image may be at stake, prompting them to immediately restore their image 6. Employees may believe that their self-esteem may be restored if they suffer shame on a particular day because of specific negative comments they received that day 10. Poor performance threatens workers’ self-evaluation. Thus they are more inclined to solve the issue by increasing task effort to repair the damage that has been done.18,49,50

Employees who feel shame about their actions are more inclined to enhance their task performance to compensate for the loss they have caused the organization and their colleagues. Aside from advancing their professional growth, employees are also concerned with maintaining a favourable social image in the company.24 Employees’ shame is anticipated to prompt them to attempt to improve their image in the sight of others.51 To exhibit their attractiveness and devotion as “good soldiers”, workers who have experienced shame are more inclined to participate in discretionary activities to demonstrate their commitment and performance.52,53 Employees’ voluntary attempts to work late, stay involved at work, help colleagues, and attend organisational events may all portray themselves as having greater task performance levels when they feel ashamed.49

H3. There is a positive relationship between shame at work and task performance.

Shame as a Mediator

In the workplace, negative feedback informs employees that their current performance falls short of expectations in a particular context. It is theoretically conceivable for supervisors to affect employee behaviour by delivering negative feedback consistent with the organization’s needs and expectations.1 Since such feedback brings attention to the disparities between employees’ performance and goals, it motivates them to increase their performance due to the experience.14 Research on evaluations for poor performance has been useful. Still, most of this research has been grounded on the notion that employees admit their underperformance after negative feedback, which has tended to portray employees as inactive recipients of the information contained in negative feedback.54 Employees may attempt to make sense of negative feedback by understanding the reason behind it, but it’s not always that simple.46 It means that individuals have a natural desire to comprehend the intentions of others, ascribe meaning to those intentions, and react accordingly to the feedback of others.55

We developed a model where shame served as a buffer between negative feedback and task performance. This approach aligns with affective events theory (AET), which states that workplace events cause emotions, influencing work attitudes and actions.2 According to AET, workplace events impact the feelings and behaviour of employees.2 Affective emotions may be elicited in the workplace by events like treatment from co-workers or other interpersonal interactions.56 Workers tend to feel better about themselves when things go their way at work, and when things go wrong, they tend to feel awful about themselves.56 Emotions have also been proven to mediate workplace occurrence and succeeding well-being and performance outcomes.57 When all of these factors are considered, it is reasonable to assume that employees’ well-being and performance will increase due to experiencing shame after receiving unfavourable supervisor feedback. While receiving negative feedback increases their likelihood of being ashamed at work and feeling weary at the end of the day, receiving more negative feedback increases their possibility of doing better the next day.

H4. Shame at work mediates the association between supervisor negative feedback and task performance.

Self-Esteem as Moderator

Negative feedback reactions are not merely a consequence of the supervisor’s ability to control their employees. In contrast to being passive receivers of feedback, individuals are active participants in the processing and managing their feedback environment to perform accordingly.58,59 Individual differences in how people react to feedback have been the subject of previous research. People’s reactions to negative feedback are influenced by their level of self-esteem (SE).60,61 Thus, individual reactions to supervisory feedback have been studied in the past. According to several studies, self-esteem (SE) influences how people react to negative feedback. Several studies have shown that those with high self-esteem can mobilize the motivational resources necessary to improve performance after receiving negative feedback.62 When people have low self-esteem, negative feedback negatively influences their self-efficacy; yet, when people have high self-esteem, negative feedback does not affect their self-efficacy.63 Individuals with low self-esteem are less likely to believe that they can improve after getting unfavourable criticism than individuals with high self-esteem who receives the same input. Individuals’ performance and self-efficacy are often tied to their efforts to deal with adverse feedback.64 As a result, those with high SE who get negative feedback are more inclined to exert extra effort to enhance their performance while, those with low SE may react by simply giving up.65 Brockner66 found that persons who score highly on SE are less likely to be affected by external or social signals or rely on external information to reduce ambiguity. Campbell67 conducted a follow-up study and found that people with high SE have higher self-confidence and produce more consistent self-evaluations over time. More importantly, those with high self-esteem tend to create more favourable self-evaluations68.They are less likely to believe that negative performance feedback accurately represents their performance.69

H5. SE moderates the relationship between supervisor negative feedback and task performance, such that this positive association is stronger when SE is high rather than low.

Method

Population and Sample

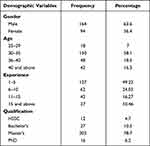

For this study, employees working full-time in educational institutions across Pakistan were selected to collect data from the administrative staff. The education sector is one of the largest sectors of Pakistan and such types of events are occurring on daily basis. Convenient sampling techniques were applied in this study. Before collecting data, all employees were contacted through emails, telephone and social media to contribute to the survey. The data were collected in three phases to reduce the problem of the common method bias. Data were collected regarding respondents’ demographics and negative supervisor feedback in the first phase. Response at the first phase was phenomenal, and we received 447 responses out of 467 (95.71%). In the second phase, we collected data regarding shame and task performance. In the second phase, we received 332 responses out of 447 (74.27%). In the last phase, we collected data regarding self-esteem. At this stage, we received 272 responses out of 332 employees, with a response rate of 81.92%. After data collection, we thoroughly checked to put data in the SPSS for results. SPSS version 25 was used to analyzed the data as it is more friendly and multiple analysis can be done through it. Fourteen questionnaires had missing data, so we excluded those questionnaires. We have the final complete data of 258 employees (94.85%). Table 1 shows the profile of the respondents.

|

Table 1 Sample Characteristics |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

Table 2 represents the standard deviations, correlation and means values of the main variables of the study. Matching with theoretical prospects, the correlations of negative supervisor feedback, self-esteem, shame and task performance have strongly correlated with one another and strongly correlated between shame and task performance (r = 0.446, p < 0.01). See Table 2 for further details.

|

Table 2 Mean, SD, Correlations, HTMT and Reliability (N= 258) |

Control Variables

Several variables were kept under control. Individual demographics (such as age, gender, and educational level) have been found to impact employees’ shame and task performance in the past, so it was kept under control.70,71 According to previous studies, age and experience reduce employees performance.72

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To measure and verify the discriminability of the measures, we arrange confirmatory factor analyses. We incorporated study variables NSF, self-esteem, shame, and TP to check model structure fitness. Table 3 shows that the four-factor model best fits the data compared to other models (X2 =3274, df=1247, TLI=0.90, CFI=0.91, RMSEA=0.03, SRMR=0.04).

|

Table 3 Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (N=258) |

Measurement Model

The construct reliability, construct convergent validity, and construct discriminant validity of the measurement model was evaluated to assess whether or not the measurement model was acceptable It is common practice to assess construct reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. A value greater than or equal to 0.7 must be present in both cases.73–75 Table 2 demonstrates that all constructs’ alpha and CR values are more than 0.7 for all variables. The consistency between items has been verified. The items must have a factor loading of 0.7 or greater to be considered concurrent Hair Jr, Sarstedt,75 as indicated in Table 4. While the construct must measure at least 50% of the variation in the construct, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each of the constructs must be at least 0.5.75 As indicated in Table 2, both item-level and construct-level convergent validities are found, with minimum loading for each construct exceeding 0.7 and AVE above 0.5, respectively. The discriminant validity shows that the model’s constructs are distinct. The study used the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio to determine discriminant validity. When the HTMT ratio is smaller than 0.9, discriminant validity is established.76 Table 2 shows that all constructs have an HTMT ratio of less than 0.9, indicating discriminant validity. The findings demonstrate that the measurement model is suitable for measuring the constructs in the model.

|

Table 4 Items Loadings |

Measures

Supervisor Negative Behavior

We assessed negative feedback using a four-item scale adopted from from Steelman, Levy77 eight-item positive and negative feedback scale. Items for negative feedback were “today my supervisor told me that I made a mistake at work”. “Today, my supervisor told me that I didn’t meet some deadlines”. “Today, my supervisor told me that my job performance fell below what is expected”. “Today, my supervisor told me that my work performance did not meet organisational standards.”

Shame

To Measure shame, we used three items scale developed by Han, Duhachek.78 An example of items are “I feel embarrassed”. “I feel ashamed” and “I feel humiliated.”

Task Performance

We assessed task performance by using a five-item scale developed by Zellmer-Bruhn and Gibson79 with modification. Sample items are “I achieve my goals”, I accomplish my objectives.”

Self-Esteem

We assessed task performance by using the 11-items scale developed by Bearman and Brückner80 with modification. Sample items are “I have a lot to be proud of”, “I feel like I am doing everything just about right”.

Results

Direct Paths and Mediation

As shown in Table 5, H1, H2, and H3 are tested for direct relationships. The results follow the assumptions developed in the literature. There is a significant positive relationship between NSB and TP (b = 0.642, p<0.000), hence, Hypothesis H1 is supported. Followed by Hypotheses H2, NSF is positively linked to shame (b=0.257, p< 0.000) and H3, where shame is positively correlated to TP (b=0.494, p< 0.000) and is also consistent with our theoretical arguments stated earlier in our model. Shame regulated the mediating route from NSF to task performance. As shown in Table 6, shame partially mediates the relationship between NSF and task performance (BootLLCI= 0.0614, and BootULLCI= 0.1527). As zero is not contained in the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect, supporting the study’s fourth hypothesis (H4). Our mediation model explained approximately 64% of the variance between NSF and task performance.

|

Table 5 Path Analysis (Direct Path’s) |

|

Table 6 Mediation Analysis |

Moderation

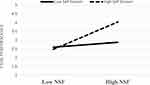

Hayes (2017) Process Macro Model 1 has been applied to test the moderation. Table 7 and Figure 1, show the moderating effects of self-esteem on the relationships between NSF and team performance (b=−.0813, SE.0279, t=−2.9105, p= 0.003, [LLCI= −0.1363 ULCI −0.0263], supporting H5 Hypotheses, such that a self-esteem strengthens the relationship. Table 7 shows the results of the moderated path analysis. To make the moderating impact of self-esteem more visible, this research computed two kinds of self-esteem mean: one with a standard deviation and the other with a lower standard deviation, as suggested by Aiken and West (1991). Figure 2 depicts the interactive mode, confirming Hypothesis 3.

|

Table 7 Moderation Analysis |

|

Figure 2 The moderating role of self-esteem between supervisor negative feedback and task performance. |

General Discussion

To examine, why and how supervisor negative feedback links to employee task performance. Grounding on affective event theory, we find that supervisor negative feedback positively enhances employee’s task performance. Further, this study confirms the mediating role of shame after receiving negative feedback from a supervisor. This study confirms that those with high self-esteem (SE) are better able to mobilise the motivating resources necessary to enhance their performance after receiving negative feedback. People with low self-esteem are more likely to be negatively impacted by negative feedback than those with strong self-esteem. These results extend the existing knowledge of how workers evaluate and react to negative feedback, and they have substantial implications for supervisors and companies that want to increase the efficacy of negative feedback.

Theoretical Implications

Many theoretical implications may be drawn from our research. First, the research contributes to the literature on the causes and repercussions of supervisor negative feedback, as well as its effect on employee task performance. Negative feedback is given to assist an employee in changing their behaviour to improve their performance and productivity in the workplace. Negative feedback has to be directed at particular conduct and communicated as soon as possible after the behaviour in question has taken place for it to be effective3,5,81.

Second, this study contributes to the literature on how shame is elicited in the workplace after facing supervisor negative feedback. According to this study, negative feedback from supervisors causes shame in employees. Previous research also shows that negative feedback is a potent elicitor of shame among employees.9 Negative feedback from supervisors increases feelings of shame in workers, even when the supervisor and employee have an excellent working relationship. It is crucial to emphasize that we are not arguing that negative feedback is the sole antecedent. It would be beneficial to rely on the concept of identity threat to discover additional activities that either elicit or prevent employees’ shame. Previous research has shown that people are more likely to retreat after experiencing shame.11 Our study adds to the body of knowledge about the implications of shame. Shame may serve as a warning mechanism for identity risks, prompting people to protect, defend, and restore their identities to lessen the likelihood of such threats occurring.18 The restoration motive often results positively and increases task performance. One important factor is the belief in one’s own power to repair one’s self-image.12 Hendriks, Muris14 stated that one way to restore and keep motives is to calculate the time sequence, indicating that “shame first motivates approach behavior (and that when this is not possible or too risky shifts to avoidance behavior)”. The overall emotion research implies that the influence of emotions on a short-term experience might be distinct from their collective effect over a longer period.82,83

Third, we argued that employees dealing with feelings of shame and guilt will strive harder to complete a failed project to perform tasks in a better way, which will eventually result in better outcomes. There is strong evidence that workers who get negative feedback are more likely to have a positive reaction, positively affecting job performance.28,84 Indeed, there has been a growing need for research to study specific emotions rather than a more generalized approach to studying human behavior.29,85,86 As an option to use an accumulated affective dimension, we provide a more in-depth recognizing of the critical role that shame plays in the relationship between negative feedback and employee outcomes, demonstrating that negative feedback raises the experience of shame, which improves performance. Fourth, these results also add to the body of knowledge on self-esteem. Self-esteem has a major role in the relationship between negative feedback and task performance.10,87 Despite its prevalence in theories, SE as a buffering mechanism has not been tested explicitly. Most research implies that self-esteem functions as a social resource that may help people cope with the negative consequences of negative experiences.31,88 Based on our findings, persons with high self-esteem react less adversely to negative feedback from their bosses.

Practical Implications

The results of our study have many implications for managers and organizations. First, our study focuses on the perceived intentions and mechanisms behind supervisor negative feedback. Our findings indicated that feedback, and subordinates’ motivation for supervisor feedback, explain around 64% of the variance in employee motivation to perform. Negative feedback presented with a constructive intent is not guaranteed to be seen as beneficial by all members of an organisation’s workforce.89 Negative feedback may be more helpful if supervisors respond to an employee’s concerns about negative feedback in a manner that motivates the individual to improve their performance rather than dismissing the concerns. Supervisors tend to be unclear when giving negative feedback since they provoke a conflict by providing unfavourable comments.77 Supervisors may benefit from training in communication skills and linguistic tactics for delivering feedback to guarantee that their workers see their comments as credible. Workers’ positive attributions may be strengthened by supervisors regularly acting constructively and ensuring that employees believe that their bosses are following the rules of the business. Second, negative feedback’s efficacy is shown to be closely linked to one’s self-esteem, according to the findings of this research. To further strengthen the impacts of negative feedback on employee’s task performance, organisations and supervisors are urged to identify measures to increase workers’ positive self-esteem. Organisations should pay greater attention to candidates with high self-esteem in their recruiting and selection procedures. Organisations may use self-efficacy training to help workers with poor self-esteem or self-restorative activities.90 This kind of training may improve an employee’s self-confidence and resilience. Third, our results may be useful for those who have difficulty dealing with negative feedback. Employees prefer to attribute supervisory behaviour to internal factors such as an annoying personality. Even when supervisors offer comments out of goodwill, this bias may lead to a misperception of supervisors’ genuine intentions. At this time, the employee’s intuitive attribution may be incorrect. The use of role-playing and experiential activities in training programs may help organisations reduce employee attribution bias91.

Limitations and Future Research

There are various limitations to this research. First, we examined the link between negative feedback and workers’ task performance from an employee’s identity viewpoint. Employees’ desire to perform better probably allows them to attain better levels of achievement in their tasks. Since feedback is delivered as part of a continuous process Xing, Sun,12 the link between negative feedback and the desire to perform may be bidirectional. Negative feedback would thus enhance or lower an employee’s performance depending on how it was attributed, which would diminish or increase the likelihood of receiving further negative feedback. The present study did not enable us to investigate the potential of a reciprocal loop. A longitudinal study design using cross-lagged modelling is recommended for future studies to evaluate the potential and establish more conclusive results. Second, researchers are supposed to determine diverse attributions to extend findings. An implicit degree of confidence is connected with each attribution made at the same moment.92,93 Researchers must concentrate on how each attribution foresees feedback outcomes, despite employees demonstrating distinct personality features when they make mixed-up attributions. For example, an employee may believe that their boss offers them negative feedback to help them perform better, but they may also think that the supervisor is in an evil mood. The employee’s future motivation and conduct may vary from those who sincerely feel that negative criticism is based only on their work performance. Third, our study sample contained full-time education sector employees, therefore generalising the patterns of findings to other groups should be done with care. In specific, collectivist cultures give more attention to personal success and failures since persons who are affiliated to a group from which a member diverts from society’s rules feel ashamed, based upon a sense of collective responsibility. Chinese employees may be more likely to feel shame due to collectivist culture. That shame serves a more useful role in controlling actions. However, it is crucial to highlight that research has shown that emotional reaction patterns to workplace events are not tied to a specific cultural setting, which is vital to remember. Additionally, our data show that workplace shame negatively impacts task performance, similar to other studies. Nonetheless, it would be beneficial if future research could reproduce similar findings in different organisations, sectors, or cultures to enhance findings further.

Fourth, our study only focused on shame as an emotional reaction to negative feedback in this study. Supervisor comments may also elicit other employee feelings, such as anger, fear, and grief, affecting employees’ performance94,95. Cazeau, Leclercq96 recommended a study that finds pairs of emotions rather than single emotions to distinguish them better. Future studies are thus advised to examine the concurrent roles performed by a wide range of emotions intimately linked to one another in the human experience. While both anger and shame are unpleasant emotions, they vary in terms of the agency of responsibility—that is, workers are more likely to feel shame when they believe they are the wrongdoing and more likely to feel anger when they think others are the wrongdoer. Given the essential responsibilities that supervisors and colleagues play in organisations, their qualities may significantly impact how employees perceive feedback. For example, in the case of supervisors and workers, one potentially significant moderator is the quality of the connection between them, such as supervisor-subordinate guanxi (SSG), which is further to be examined. They reflect employees’ relationship schemas and guide them to create new interactions with their bosses and colleagues. Workers that have good supervisor connections are encouraged to portray their bosses in a favourable light by reciprocity norms, which often results in external attributions regarding negative feedback.

Conclusion

By studying the origins and consequences of shame in the workplace, this research adds to the growing research on the impacts of shame on employee performance. We determine that receiving negative feedback from a supervisor is connected with feelings of shame, which is associated with higher levels of job performance. Self-esteem contributes to strengthening this relationship, increasing our understanding of how shame is developed and how shame may be used to enhance task performance. Overall, these findings emphasize the need of continuing to pay attention to this area of shame research in the future.

Data Sharing Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Ethical Standards

The University Review committee (U.R.C.) involving Human Subjects for Department of Business Administration, Iqra National University, Peshawar Pakistan, has reviewed the proposal stated above and confirmed that all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The participate of this study was the employees working full-time in educational institutions across, Pakistan. Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study to publish this paper. Further, formal approval was obtained from the competent authorities of the organizations that participated in the study. The university research committee approved all the procedures on research involving Human Subjects of Iqra National University, Peshawar Pakistan.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Xing L, Sun JM, Jepsen D. Feeling shame in the workplace: examining negative feedback as an antecedent and performance and well‐being as consequences. J Organ Behav. 2021;42(9):1244–1260. doi:10.1002/job.2553

2. Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory. Res Org Behav. 1996;18(1):1–74.

3. Fu C, Ren Y, Wang G, et al. Fear of future workplace violence and its influencing factors among nurses in Shandong, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00644-w

4. Ružojčić M, Galić Z, Jerneić Ž. How does implicit aggressiveness translate into counterproductive work behaviors? The role of job satisfaction and workplace anger. Int J Selection Assess. 2021;29(2):269–284. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12327

5. Mousa M, Massoud HK, Ayoubi RM. Gender, diversity management perceptions, workplace happiness and organisational citizenship behaviour. Int J. 2020;15:1249.

6. Feinberg M, Ford BQ, Flynn FJ. Rethinking reappraisal: the double-edged sword of regulating negative emotions in the workplace. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;161:1–19. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.03.005

7. Naeem M. Using social networking applications to facilitate change implementation processes: insights from organizational change stakeholders. Bus Process Manage J. 2020;26(7):1979–1998. doi:10.1108/BPMJ-07-2019-0310

8. Burton N, Vu MC. Moral identity and the Quaker tradition: moral dissonance negotiation in the workplace. J Bus Ethics. 2021;174(1):127–141. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04531-3

9. Lyons BJ, Lynch JW, Johnson TD. Gay and lesbian disclosure and heterosexual identity threat: the role of heterosexual identity commitment in shaping de-stigmatization. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:1–18. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.03.001

10. Hillebrandt A, Barclay LJ. How cheating undermines the perceived value of justice in the workplace: the mediating effect of shame. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(10):1164. doi:10.1037/apl0000485

11. Goffnett J, Liechty JM, Kidder E. Interventions to reduce shame: a systematic review. J Behav Cognit Therapy. 2020;30(2):141–160. doi:10.1016/j.jbct.2020.03.001

12. Xing L, Sun J, Jepsen DM. The Short-Term Effects of Supervisor Negative Feedback on Employee Well-Being and Performance.

13. Alam M, Singh P. Performance feedback interviews as affective events: an exploration of the impact of emotion regulation of negative performance feedback on supervisor–employee dyads. Human Resour Manage Rev. 2021;31(2):100740. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100740

14. Hendriks E, Muris P, Meesters C. The Influence of Negative Feedback and Social Rank on Feelings of Shame and Guilt: a Vignette Study in 8-to 13-Year-Old Non-Clinical Children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021;1:1–11.

15. Zada S, Khan J, Saeed I, et al. Servant Leadership Behavior at Workplace and Knowledge Hoarding: a Moderation Mediation Examination. Front Psychol. 2022;13;2300.

16. Alkheyi A, Khalifa GS, Ameen A, et al. Strategic leadership practices on team effectiveness: the mediating effect of knowledge sharing in the UAE Municipalities. Acad Leadersh. 2020;21(3):99–112.

17. Klaic A, Burtscher MJ, Jonas K. Fostering team innovation and learning by means of team‐centric transformational leadership: the role of teamwork quality. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2020;93(4):942–966. doi:10.1111/joop.12316

18. Daniels MA, Robinson SL. The shame of it all: a review of shame in organizational life. J Manage. 2019;45(6):2448–2473. doi:10.1177/0149206318817604

19. Kramer U, Pascual-Leone A, Rohde KB, et al. The role of shame and self‐compassion in psychotherapy for narcissistic personality disorder: an exploratory study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2018;25(2):272–282. doi:10.1002/cpp.2160

20. Bagozzi RP, Sekerka LE, Sguera F. Understanding the consequences of pride and shame: how self-evaluations guide moral decision making in business. J Bus Res. 2018;84:271–284. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.036

21. Li G, Xie L. The effects of job involvement and supervisor developmental feedback on employee creativity: a polynomial regression with response surface analysis. Curr Psychol. 2022;1–12.

22. Su W, Xiao F. Supervisor positive feedback and employee performance: promotion focus as a mediator. Social Behav Personality. 2022;50(2):1–9.

23. Lyubykh Z, Bozeman J, Hershcovis MS, et al. Employee performance and abusive supervision: the role of supervisor over‐attributions. J Organ Behav. 2022;43(1):125–145. doi:10.1002/job.2560

24. Cucuani H, Sulastiana M, Harding D, et al. The Meaning of Shame for Malay People in Indonesia and Its Relation to Counterproductive Work Behaviors in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Springer. 2021;4:73–89.

25. Dawson P, Henderson M, Mahoney P, et al. What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives. Assess Evaluation Higher Educ. 2019;44(1):25–36. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

26. Afzal S, Arshad M, Saleem S, et al. The impact of perceived supervisor support on employees’ turnover intention and task performance: mediation of self-efficacy. J Manage Dev. 2019;38(5):369–382. doi:10.1108/JMD-03-2019-0076

27. Khan J. The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion in the Relationship between Abusive Supervision and Employee Cyberloafing Behaviour. J Manage Res. 2021;23:160–178.

28. Jawahar I, Schreurs B. Supervisor incivility and how it affects subordinates’ performance: a matter of trust. Personnel Rev. 2018;47(3):709–726. doi:10.1108/PR-01-2017-0022

29. Guan X, Frenkel SJ. Explaining supervisor–subordinate guanxi and subordinate performance through a conservation of resources lens. Human Relations. 2019;72(11):1752–1775. doi:10.1177/0018726718813718

30. Singh SK. Territoriality, task performance, and workplace deviance: empirical evidence on role of knowledge hiding. J Bus Res. 2019;97:10–19. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.034

31. Chae H, Choi JN. Contextualizing the effects of job complexity on creativity and task performance: extending job design theory with social and contextual contingencies. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2018;91(2):316–339. doi:10.1111/joop.12204

32. Ilgen DR, Fisher CD, Taylor MS. Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. J Appl Psychol. 1979;64(4):349. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.64.4.349

33. Potipiroon W, Ford MT. Relational costs of status: can the relationship between supervisor incivility, perceived support, and follower outcomes be exacerbated? J Occup Organ Psychol. 2019;92(4):873–896. doi:10.1111/joop.12263

34. Ashford SJ, Tsui AS. Self-regulation for managerial effectiveness: the role of active feedback seeking. Acad Manage j. 1991;34(2):251–280.

35. Ullah R, Zada M, Saeed I, et al. Have you heard that—“GOSSIP”? Gossip spreads rapidly and influences broadly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13389. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413389

36. Podsakoff PM, Farh J-L. Effects of Feedback Sign and Credibility on Goal Setting and Task Performance: a Preliminary Test of Some Control Theory Propositions.

37. Nease AA, Mudgett BO, Quiñones MA. Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(5):806. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.806

38. Keltner D. Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: a study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cogn Emot. 1996;10(2):155–172. doi:10.1080/026999396380312

39. Turner JE. Researching state shame with the experiential shame scale. J Psychol. 2014;148(5):577–601. doi:10.1080/00223980.2013.818927

40. Bynum IV. Filling the feedback gap: the unrecognised roles of shame and guilt in the feedback cycle. Med Edu. 2015;49(7):644–647. doi:10.1111/medu.12754

41. Scheff T, Daniel GR, Sterphone J. Shame and a Theory of war and violence. Aggress Violent Behav. 2018;39:109–115. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.006

42. Ashforth BE. Which hat to wear. Social Identity Processes Org Contexts. 2001;2:32–48.

43. Ma J, Peng Y. The performance costs of illegitimate tasks: the role of job identity and flexible role orientation. J Vocat Behav. 2019;110:144–154. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.012

44. Bandura A. Applying theory for human betterment. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(1):12–15. doi:10.1177/1745691618815165

45. Zhu R, Wu H, Xu Z, et al. Early distinction between shame and guilt processing in an interpersonal context. Soc Neurosci. 2019;14(1):53–66. doi:10.1080/17470919.2017.1391119

46. Teimouri Y. Differential roles of shame and guilt in L2 learning: how bad is bad? Modern Lang J. 2018;102(4):632–652. doi:10.1111/modl.12511

47. Tonelli L. Shame! Whose Shame, Is It? A Systems Psychodynamic Perspective on Shame in Organisations: a Case Study, in The Bright Side of Shame. Bright Side Shame. 2019;235–249.

48. Chen X, Huang C, Wang H, et al. Negative emotion arousal and altruism promoting of online public stigmatization on COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1848.

49. Messing K. Bent Out of Shape: Shame, Solidarity, and Women’s Bodies at Work. Between the Lines; 2021.

50. Liu S, He X, Chan FTS, et al. An Extended Multi-Criteria Group Decision-Making Method with Psychological Factors and Bidirectional Influence Relation for Emergency Medical Supplier Selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;202:117414. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117414

51. Kim YK, Kammeyer-Mueller J. Antecedents and consequences of self-conscious emotions at work: guilt, shame, and pride.

52. Bolino MC. Citizenship and impression management: good soldiers or good actors? Acad Manage Rev. 1999;24(1):82–98. doi:10.2307/259038

53. Saeed I, Khan J, Zada M, et al. Linking Ethical Leadership to Followers’ Knowledge Sharing: mediating Role of Psychological Ownership and Moderating Role of Professional Commitment. Front Psychol. 2022;13:841590. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841590

54. Whitney AE. Shame in the writing classroom. English J. 2018;107(3):130–132.

55. Claesson K, Birgegard A, Sohlberg S. Shame: mechanisms of Activation and Consequences for Social Perception, Self‐Image, and General Negative Emotion. J Pers. 2007;75(3):595–628. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00450.x

56. Weiss HM, Beal DJ. Reflections on Affective Events Theory, in the Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2005.

57. Ashton-James CE, Ashkanasy NM. Affective Events Theory: A Strategic Perspective, in Emotions, Ethics and Decision-Making. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2008.

58. Brown JD. High self-esteem buffers negative feedback: once more with feeling. Cogn Emot. 2010;24(8):1389–1404. doi:10.1080/02699930903504405

59. Ilies R, De Pater IE, Judge T. Differential affective reactions to negative and positive feedback, and the role of self‐esteem. J Manage Psychol. 2007;22(6):590–609. doi:10.1108/02683940710778459

60. Pettit JW, Joiner, Jr TE. Negative life events predict negative feedback seeking as a function of impact on self-esteem. Cognit Ther Res. 2001;25(6):733–741. doi:10.1023/A:1012919306708

61. van Schie CC, Chiu C-D, Rombouts SARB, et al. Stuck in a negative me: fMRI study on the role of disturbed self-views in social feedback processing in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med. 2020;50(4):625–635. doi:10.1017/S0033291719000448

62. Burrow AL, Rainone N. How many likes did I get?: purpose moderates links between positive social media feedback and self-esteem. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;69:232–236. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.09.005

63. Valkenburg PM, Koutamanis M, Vossen HG. The concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents’ use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Comput Human Behav. 2017;76:35–41. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.008

64. Luerssen A, Ayduk Ö. Self‐esteem and anxious responses to partner feedback: parsing anticipatory and consummatory anxiety. Pers Relatsh. 2019;26(1):137–157. doi:10.1111/pere.12270

65. Will G-J, Rutledge RB, Moutoussis M, et al. Neural and computational processes underlying dynamic changes in self-esteem. Elife. 2017;6:e28098. doi:10.7554/eLife.28098

66. Brockner J. Self-Esteem at Work: Research, Theory, and Practice. Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com; 1988.

67. Campbell JD. Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(3):538. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.538

68. Duy B, Yıldız MA. The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol. 2019;38(6):1456–1463. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9698-1

69. Jeung H, Walther S, Korn CW, et al. Emotional responses to receiving peer feedback on opinions in borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders. 2018;9(6):595. doi:10.1037/per0000292

70. Kiuru N, Spinath B, Clem A-L, et al. The dynamics of motivation, emotion, and task performance in simulated achievement situations. Learn Individ Differ. 2020;80:101873. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101873

71. Krishnan R, Loon KW, Tan NZ. The effects of job satisfaction and work-life balance on employee task performance. Int J Acad Res Bus Social Sci. 2018;8(3):652–662. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i3/3956

72. Doo MY, Bonk C, Heo H. A meta-analysis of scaffolding effects in online learning in higher education. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2020;21(3):60–80. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4638

73. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA; 1981.

74. Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Smith D, et al. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): a useful tool for family business researchers. J Family Bus Strategy. 2014;5(1):105–115. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.01.002

75. Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, et al. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev. 2014;1:548.

76. Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Marketing Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

77. Steelman LA, Levy PE, Snell AF. The feedback environment scale: construct definition, measurement, and validation. Educ Psychol Meas. 2004;64(1):165–184. doi:10.1177/0013164403258440

78. Han D, Duhachek A, Agrawal N. Emotions shape decisions through construal level: the case of guilt and shame. J Consumer Res. 2014;41(4):1047–1064. doi:10.1086/678300

79. Zellmer-Bruhn M, Gibson C. Multinational organization context: implications for team learning and performance. Acad Manage j. 2006;49(3):501–518. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.21794668

80. Bearman PS, Brückner H. Promising the future: virginity pledges and first intercourse. Am j Sociol. 2001;106(4):859–912. doi:10.1086/320295

81. Saeed I. To establish the link between aversive leadership and work outcomes: an empirical evidence. NICE Res J. 2017;3:161–181.

82. Kim Y. Organizational resilience and employee work-role performance after a crisis situation: exploring the effects of organizational resilience on internal crisis communication. J Public Relations Res. 2020;32(1–2):47–75. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2020.1765368

83. Saeed I, Khan J, Zada M, et al. Towards Examining the Link Between Workplace Spirituality and Workforce Agility: exploring Higher Educational Institutions. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:31.

84. Khan J, Saeed I, Fayaz M, et al. Perceived overqualification? Examining its nexus with cyberloafing and knowledge hiding behaviour: harmonious passion as a moderator. J Knowl Manage. 2022. doi:10.1108/JKM-09-2021-0700

85. Zada M, Zada S, Ali M, et al. How Classy Servant Leader at Workplace? Linking Servant Leadership and Task Performance During the COVID-19 Crisis: a Moderation and Mediation Approach. Front Psychol. 2022;13:810227. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.810227

86. Zada S, Wang Y, Zada M, et al. Effect of mental health problems on academic performance among university students in Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2021;23:395–408. doi:10.32604/IJMHP.2021.015903

87. Mayer C-H. Transforming shame in the workplace, leadership and organisation: contributions of positive psychology movements to the discourse. In: New Horizons in Positive Leadership and Change. Cham: Springer; 2020:313–331.

88. Zada M, Zada S, Khan J, et al. Does Servant Leadership Control Psychological Distress in Crisis? Moderation and Mediation Mechanism. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:607. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S354093

89. Fedor DB, Eder RW, Buckley MR. The contributory effects of supervisor intentions on subordinate feedback responses. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1989;44(3):396–414. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(89)90016-2

90. Wiesenfeld BM, Raghuram S, Garud R. Communication patterns as determinants of organizational identification in a virtual organization. Org Sci. 1999;10(6):777–790. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.6.777

91. Martinko MJ, Gardner WL. The leader/member attribution process. Acad Manage Rev. 1987;12(2):235–249. doi:10.2307/258532

92. Han Z, Liu J, Wu WN. Trust and confidence in authorities, responsibility attribution, and natural hazards risk perception. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy. 2021. doi:10.1002/rhc3.12234

93. Khan J, Farooq S, Zia MH. Towards examining the link between workplace spirituality, employee engagement and job satisfaction. Pakistan Bus Rev. 2020;21:4.

94. Motro D, Spoelma TM, Ellis AP. Incivility and creativity in teams: examining the role of perpetrator gender. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(4):560. doi:10.1037/apl0000757

95. Peng P, Wang T, Wang C, et al. A meta-analysis on the relation between fluid intelligence and reading/mathematics: effects of tasks, age, and social economics status. Psychol Bull. 2019;145(2):189. doi:10.1037/bul0000182

96. Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, et al. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N Eng J Med. 2001;344(12):873–880. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441202

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.