Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 10

Risk factors for mortality in Asian Taiwanese patients with methanol poisoning

Authors Lee C, Chang EK, Lin J, Weng C , Lee S, Juan K, Yang H, Lin C, Lee S, Wang I, Yen T

Received 24 July 2013

Accepted for publication 1 November 2013

Published 17 January 2014 Volume 2014:10 Pages 61—67

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S51985

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Chen-Yen Lee,1,* Eileen Kevyn Chang,1,* Ja-Liang Lin,1 Cheng-Hao Weng,1 Shen-Yang Lee,1 Kuo-Chang Juan,1 Huang-Yu Yang,1 Chemin Lin,2 Shwu-Hua Lee,2 I-Kwan Wang,3 Tzung-Hai Yen1

1Department of Nephrology and Division of Clinical Toxicology, 2Department of Psychiatry, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University, Taipei, Taiwan; 3Department of Nephrology, China Medical University Hospital and China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Introduction: Methanol poisoning continues to be a serious public health issue in Taiwan, but very little work has been done to study the outcomes of methanol toxicity in the Asian population. In this study, we examined the value of multiple clinical variables in predicting mortality after methanol exposure.

Methods: We performed a retrospective observational study on patients with acute poisoning who were admitted to the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital over a period of 9 years (2000–2008). Out of the 6,347 patients, only 32 suffered methanol intoxication. The demographic, clinical, laboratory, and mortality data were obtained for analysis.

Results: Most patients were middle aged (46.1±13.8 years), male (87.5%), and habitual alcohol consumers (75.0%). All the poisonings were from an oral exposure (96.9%), except for one case of intentionally injected methanol (3.1%). After a latent period of 9.3±10.1 hours, many patients began to experience hypothermia (50.0%), hypotension (15.6%), renal failure (59.4%), respiratory failure (50.0%), and consciousness disturbance (Glasgow coma scale [GCS] score 10.5±5.4). Notably, the majority of patients were treated with ethanol antidote (59.4%) and hemodialysis (58.1%). The remaining 41.6% of patients did not meet the indications for ethanol therapy. At the end of analysis, there were six (18.8%), 15 (46.9%), and eleven (34.4%) patients alive, alive with chronic complications, and dead, respectively. In a multivariate Cox regression model, it was revealed that the GCS score (odds ratio [OR] 0.816, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.682–0.976) (P=0.026), hypothermia (OR 168.686, 95% CI 2.685–10,595.977) (P=0.015), and serum creatinine level (OR 4.799, 95% CI 1.321–17.440) (P=0.017) were significant risk factors associated with mortality.

Conclusion: The outcomes (mortality rate 34.4%) of the Taiwanese patients subjected to intensive detoxification protocols were comparable with published data from other international poison centers. Furthermore, the analytical results indicate that GCS score, hypothermia, and serum creatinine level help predict mortality after methanol poisoning.

Keywords: wood alcohol, intoxication, ethanol, hemodialysis, mortality

Introduction

Methanol poisoning continues to be a serious public health issue in Taiwan. Also known as wood alcohol, methanol is a component of washing fluids, antifreeze formulations, photocopying fluids, perfumes, and paint removers. Since it is cheap and easy to obtain, it is used in the production of illegal alcoholic beverages in many developing countries.1

The management of methanol poisoning includes standard supportive care, correction of metabolic acidosis, administration of folinic acid, provision of an antidote to inhibit the metabolism of methanol to formate, and selective hemodialysis to correct severe metabolic abnormalities and enhance methanol and formate elimination. Although both ethanol and fomepizole are effective, fomepizole is the preferred antidote for methanol poisoning.2 According to a systematic review,3 the mortality in patients treated with ethanol was 21.8% and in those administered fomepizole, was 17.1%. The mortality in patients treated with both antidotes was 5.5%.3 In terms of pharmacodynamics, it has been reported that fomepizole induces its own metabolism via cytochrome P-450, leading to enhanced fomepizole elimination and 4-carboxypyrazole excretion. Thus, to maintain relatively constant plasma levels of fomepizole during therapy, increased supplemental doses are needed at about 36–48 hours to overcome the increased elimination of fomepizole.4

One of the rationales for this study was that very little work5,6 has been done to study the outcomes of Asian patients with methanol poisoning. Another consideration was that epidemiologic studies have found that the rates of alcohol use and alcoholism are lower in persons of Asian descent than in other ethnic groups. One possible reason is that about half of Asians have a deficiency of the low-Michaelis constant (Km), mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) isoenzyme, which is responsible for metabolizing acetaldehyde.7 Many Taiwanese patients may also be ALDH2-deficient and therefore may not be able to metabolize either formaldehyde or therapeutic ethanol and may develop a different syndrome of methanol poisoning, or when given ethanol, may have adverse reactions, such as flushing, etc.

Another consideration is the increasing use of the Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score as a predictor of mortality after various neurologic insults. The GCS score was introduced in 19748 and aimed at standardizing the assessment of the consciousness level in patients with head injury. It has been mainly used in evaluating prognosis, comparing different groups of patients, and for monitoring neurological status. However, nowadays, the use of the scale has been expanded beyond its original intention. For example, in a recent study of carbon monoxide poisonings,9 it was reported that although there was no significant correlation between the carboxyl hemoglobin level and the duration of inpatient treatment, a significant inverse correlation did exist between the GCS score and the duration of inpatient treatment. In other words, a higher GCS score predicts better prognosis.

Therefore, this study examined the clinical features, GCS scores, physiological markers, and clinical outcomes of Taiwanese patients after methanol poisoning and sought to determine what association, if any, might exist between these findings. Most importantly, the study investigated predictors of the GCS score and evaluated the GCS score as a predictor of mortality after methanol poisoning.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational study complied with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, a tertiary referral center located in the northern part of Taiwan. Since this study involved a retrospective review of existing data, the Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, but specific informed consent from patients was not required. The Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital specifically waived the need for consent; however, informed consent regarding the risks of acute methanol poisoning and all treatment modalities (including cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation, etc) had been obtained from all patients on their initial admission. In addition, all individual information was securely protected (by delinking identifying information from main data set) and available to only the investigators. Furthermore, all the data were analyzed anonymously. Finally, all the primary data were collected according to epidemiology guidelines for strengthening the reporting of observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). The policy described above was based on a previous publication.10

Patients

Between 2000 and 2008, a total of 32 out of 6,347 poisoned patients were referred for the management of methanol poisoning. The patients were diagnosed with methanol poisoning on the basis of their history and physical and laboratory findings; their condition was confirmed by blood sampling, which was performed to measure the blood methanol concentration. The data were collected on admission. Blood methanol was detected using gas chromatography; the limit of detection was <0.15 mg/dL, and the toxic level was >20.00 mg/dL.

GCS score

The GCS score comprises three tests: ocular, verbal, and motor responses. The three separate values are considered as well as their sum. The lowest possible total GCS score is 3 (deep coma or death), while the highest is 15 (fully awake person).8

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adult patients aged 18 years and older were included in this study if they had a positive history of methanol ingestion or injection, and also tested positive for blood methanol concentration. Patients who did not have detectable blood methanol levels were excluded from the study regardless of whether they had a history of methanol ingestion or injection. Finally, patients with epilepsy were also excluded.

Methanol detoxification protocols

The protocols included gastric lavage with large amounts of normal saline followed by infusion of 1 g/kg activated charcoal and 250 mL magnesium citrate via a nasogastric tube. The magnesium citrate was used to prevent constipation after the charcoal administration. Forced emesis was avoided. Because folinic acid is not available in our hospital, folic acid was used to enhance formic acid metabolism. Similarly, because fomepizole is not available in our hospital, ethanol was used as soon as possible after methanol ingestion or injection, to prevent the production of formate. The indications for the use of ethanol2 were: 1) a plasma methanol concentration of >20 mg/dL; 2) recent history of ingesting toxic amounts of methanol and an osmolal gap of >10 mOsm/kg H2O; or 3) strong clinical suspicion of methanol poisoning with at least two of the following parameters: arterial pH <7.3, serum bicarbonate <20 meq/L, and osmolal gap >10 mOsm/kg H2O. On the other hand, hemodialysis was considered for the following conditions:2 significant metabolic acidosis (pH <7.25−7.30); abnormality of vision; deteriorating vital signs despite intensive supportive care; renal failure; electrolyte imbalance unresponsive to conventional therapy; and/or serum methanol concentration of >50 mg/dL.

Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis was performed for 4−6 hours via bilateral femoral catheters.11 Bilateral femoral catheters were used, rather than a single double-lumen catheter, to avoid access recirculation. The blood and dialysate flow were 200 and 500 mL/min, respectively. The dialyzer was a modified cellulose-based polyamide or polysulfone membrane, and the dialysate was a bicarbonate-based buffer with a standard ionic composition.

Covariates

Acute renal failure was diagnosed if the serum creatinine increased to greater than 1.4 mg/dL (reference range: 0.4−1.4 mg/dL).12 Acute respiratory failure was defined as a condition of respiratory insufficiency requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours, regardless of the fraction of inspired oxygen.13 Hypothermia was defined as a decrease in core body temperature to less than 36.0°C.14 Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg.15 Chronic complications after severe methanol poisoning included basal ganglia necrosis with parkinsonian features and blindness.2

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were expressed as the means ± standard deviations for the number of observations, whereas the categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). Nonnormal distribution data were presented as median (range). Before analysis, all the data were routinely tested for normality of distribution and equality of standard deviation. For comparisons between groups, the Student’s t-test was used for quantitative variables, whereas the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A simple linear regression analysis was used to compare the frequency of potential risk factors associated with the GCS score. To control for confounding factors, a multiple linear regression analysis (stepwise backward approach) was performed for the significant variables (P<0.05) that were identified by the simple linear regression analysis. The survival data were compared with the Kaplan−Meier method and tested for significance using the logrank test. A univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to compare the frequency of potential risk factors associated with mortality. Similarly, to control for confounding factors, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to analyze the factors that were significant on univariate analysis and that met the assumptions of a proportional hazard model. The criterion for significance to reject the null hypothesis was a 95% confidence interval (CI). The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20 for Mac (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

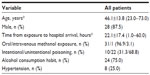

A summary of the baseline characteristics of the patients with methanol poisoning is shown in Table 1. Most patients were middle aged (46.1±13.8 years [23.0−73.0]), male (87.5%), and habitual alcohol consumers (75.0%). All poisonings were from oral exposure (96.9%), except for one case of intentionally injected methanol (3.1%).

| Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients with methanol poisoning (n=32) |

After a latent period of 9.3±10.1 (0.0–36.0) hours, many patients began to experience hypothermia (50.0%), hypotension (15.6%), renal failure (59.4%), respiratory failure (50.0%), and consciousness disturbance (GCS 10.5±5.4) (Table 2). The laboratory findings also revealed a severe high anion gap (32.7±15.4 mmol/L), high osmolal gap (53.4±35.5 mOsm/kg H2O), and metabolic acidosis (pH 7.0±0.2, partial pressure of CO2 [pCO2 mmHg] 26.3±14.3, bicarbonate 6.7±5.0 mmol/L, and base excess −38.1±23.5 mmol/L). Notably, the majority of the patients were treated with ethanol antidote (59.4%) and hemodialysis (58.1%).

At the end of the study period, there were six (18.8%), 15 (46.9%), and eleven (34.4%) patients alive, alive with chronic complications, and dead, respectively (Table 2).

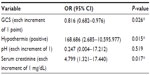

An analysis of the risk factors associated with mortality in the patients with methanol poisoning is shown in Table 3. In a multivariate Cox regression model, it was revealed that the GCS score (odds ratio [OR] 0.816, 95% CI 0.682−0.976) (P=0.026), hypothermia (OR 168.686, 95% CI 2.685−10595.977) (P=0.015), and the serum creatinine level (OR 4.799, 95% CI 1.321−17.440) (P=0.017) were significant risk factors associated with mortality.

Discussion

The present study is important because it is one of the few reports5,6 on Asian patients with methanol poisoning. In addition, the clinical outcomes (mortality rate 34.4%) of the Taiwanese patients subjected to intensive detoxification protocols were comparable with published data16−23 from other international poison centers. Evidently, the favorable outcomes depended on a prompt diagnosis of methanol poisoning, standard supportive care, and correction of metabolic acidosis, as well as the immediate institution of methanol detoxification protocols. As mentioned, although Taiwanese patients may be ALDH2-deficient and therefore not be able to metabolize either formaldehyde or ethanol given therapeutically, they did not develop a different syndrome of methanol poisoning.

In terms of metabolism, alcohol dehydrogenase metabolizes methanol to formaldehyde, which is then rapidly converted to formic acid by several enzyme systems in the body.24 Formic acid accumulation accounts for the initial anion gap metabolic acidosis associated with methanol poisoning.25 Formate interrupts mitochondrial respiration by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase activity, which leads to tissue hypoxia and lactate formation.26 Formate is metabolized in the liver by a folate-dependent biochemical pathway. The rate of formate metabolism correlates with the concentration of hepatic tetrahydrofolic acid, which in turn is dependent on the serum folic acid concentration.24 There is a characteristic latent period (10−30 hours) after the initial ingestion of methanol and before the onset of symptoms. This latent period most likely corresponds to the time period during which methanol is metabolized into formaldehyde and formic acid. Visual disturbances, ranging from spotting and blurring to complete loss of vision, are the hallmark of methanol poisoning. Progressive neurological deterioration coincides with the advanced stages of poisoning. Gastrointestinal symptoms are common and nonspecific − nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, hepatitis, and pancreatitis have all been reported.27,28 The terminal event is often respiratory arrest.2 Therefore, methanol ingestion/injection results in the formation of formic acid, a toxic metabolite that can cause metabolic acidosis.29 Methanol toxicity is therefore dependent on the amount of methanol ingested, the nature of the treatment received, the elapsed time since ingestion, and the accumulation of formic acid.29 Importantly, the minimal lethal oral dose of methanol in humans is about 0.3−1.0 g/kg.30

It was revealed in this study that the GCS score (P=0.026), hypothermia (P=0.015), and the serum creatinine level (P=0.017) were significant risk factors associated with mortality. In 1998, Liu et al16 reported that 18 of 50 (36%) patients at the Toronto Hospital died of methanol poisoning. Coma or seizure on presentation and severe metabolic acidosis (pH <7) were indicators of poor prognosis.16 Davis et al23 reviewed the huge data of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System (1993−1998) and reported that the mean number of methanol exposure cases per year was 2,254. One death occurred for every 183 exposures.23 In the study by Meyer et al,17 the strongest predictor of death was a blood pH of <7.0. Some patients did not develop signs of toxicity, in spite of having potentially lethal methanol levels, ie, up to 160 mmol/L or 5,128.2 mg/dL.23 An analysis by Hovda et al19 of a methanol outbreak in Norway between 2002 and 2004 revealed that respiratory arrest, coma, and severe metabolic acidosis (pH <6.9 and base deficit >28 mmol/L) were strong predictors of poor outcome. In another study,20 poor prognosis was associated with a pH of <7, coma on admission, and >24 hours delay from intake to admission. In another outbreak in Estonia,21 68 of 154 (44%) patients died. The outcome was related to the degree of metabolic acidosis, serum methanol concentration, coma upon admission, and the patient’s ability to hyperventilate.21 Furthermore, in another case series of 16 patients22 in Tunisia, a total of three (19%) patients who required mechanical ventilation because of deep coma or shock died within 6 hours. In a study by Verhelst et al,31 acute renal injury was found in 15 of the 25 (60%) patients. The patients who developed renal injury had a lower blood pH value on admission, higher serum osmolality, and higher peak formate concentration than those in individuals of the control group.31 Hemolysis and myoglobinuria might contribute to the acute renal injury. The results of a histopathological evaluation of the kidney on a limited sample size (n=5) were inconclusive but suggestive of hydropic changes in the proximal tubule, secondary to methanol toxicity.31 Coulter et al32 analyzed the literature data of 119 patients with methanol poisoning and concluded that large osmolal gap, anion gap, and low pH (<7.22) were associated with increased mortality and that pH has the highest predictive value. Rzepecki et al33 reported that the blood concentrations of methanol and ethanol and arterial blood gas measured on admission were important prognostic factors. The most commonly encountered complication was pneumonia. Features of central nervous system damage were found in 20 cases (6.94%). Within the nonsurvivors, such complications as central nervous system damage, seizures, pneumonia, liver injury, and pancreatitis were noted more frequently, with statistical significance.33 Finally, it was suggested in a multicenter study34 that low pH (pH <7), coma (GCS score <8), and inadequate hyperventilation (pCO2 ≥3.1 kilopascal (kPa) in spite of a pH <7) on admission were the strongest predictors of poor outcome after methanol poisoning.

Following gastric lavage, most patients with methanol poisoning were treated with activated charcoal. Nevertheless, methanol is absorbed rapidly, and even if gastrointestinal decontamination techniques were effective, there would be little opportunity to prevent its absorption. Activated charcoal administration is generally discouraged due to the supposition that methanol is not adsorbed by activated charcoal. With most patients in this study admitted late, use of this technique would have been theoretically ineffective. Moreover, the uses of gastric lavage and activated charcoal in unconscious patients have been generally discouraged due to the high risk of aspiration pneumonia.35,36

In this study, it was found that only 59.4% of the patients received ethanol antidote. The reason for such a low application of ethanol therapy was that the remaining 41.6% patients did not meet the indications for ethanol usage.2

In summary, the analytical results indicate that GCS score, hypothermia, and serum creatinine level help predict mortality after methanol poisoning. However, the retrospective nature of the study, lack of control of a retrospective cohort, small patient population, short follow-up duration, and absence of formic acid or ALDH2 measurements limit the certainty of our conclusions.

Acknowledgment

Dr Tzung-Hai Yen was funded by research grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (grant number CMRG3C0771) and National Science Council of Taiwan (grant numbers NSC102-2314-B-182-044- and NSC101-2314-B-182A-102-MY2).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Giovanetti F. Methanol poisoning among travellers to Indonesia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11(3):190–193. | |

Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology Ad Hoc Committee on the Treatment Guidelines for Methanol Poisoning. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40(4):415–446. | |

Beatty L, Green R, Magee K, Zed P. A systematic review of ethanol and fomepizole use in toxic alcohol ingestions. Emerg Med Int. 2013;2013:638057. | |

McMartin KE, Sebastian CS, Dies D, Jacobsen D. Kinetics and metabolism of fomepizole in healthy humans. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50(5):375–383. | |

Teo SK, Lo KL, Tey BH. Mass methanol poisoning: a clinico-biochemical analysis of 10 cases. Singapore Med J. 1996;37(5):485–487. | |

Jiang CQ, Wu YX, Liu WW, et al. [Clinical cure for acute methanol poisoning]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2005;23(3):206–209. Chinese. | |

Wall TL, Peterson CM, Peterson KP, et al. Alcohol metabolism in Asian-American men with genetic polymorphisms of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):376–379. | |

Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–84. | |

Grieb G, Simons D, Schmitz L, Piatkowski A, Grottke O, Pallua N. Glasgow Coma Scale and laboratory markers are superior to COHb in predicting CO intoxication severity. Burns. 2011;37(4):610–615. | |

Liu SH, Lin JL, Weng CH, et al. Heart rate-corrected QT interval helps predict mortality after intentional organophosphate poisoning. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36576. | |

Lee YC, Lin JL, Lee SY, et al. Outcome of patients with lithium poisoning at a far-east poison center. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011;30(7):528–534. | |

Weng CH, Hu CC, Lin JL, et al. Sequential organ failure assessment score can predict mortality in patients with paraquat intoxication. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51743. | |

Luhr OR, Antonsen K, Karlsson M, et al. Incidence and mortality after acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome in Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. The ARF Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(6):1849–1861. | |

Nuckton TJ, Claman DM, Goldreich D, Wendt FC, Nuckton JG. Hypothermia and afterdrop following open water swimming: the Alcatraz/San Francisco Swim Study. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(6):703–707. | |

Victorino GP, Battistella FD, Wisner DH. Does tachycardia correlate with hypotension after trauma? J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(5):679–684. | |

Liu JJ, Daya MR, Carrasquillo O, Kales SN. Prognostic factors in patients with methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(3):175–181. | |

Meyer RJ, Beard ME, Ardagh MW, Henderson S. Methanol poisoning. N Z Med J. 2000;113(1102):11–13. | |

Brent J, McMartin K, Phillips S, Aaron C, Kulig K; Toxic Alcohols Study Group. Fomepizole for the treatment of methanol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(6):424–429. | |

Hovda KE, Hunderi OH, Tafjord AB, Dunlop O, Rudberg N, Jacobsen D. Methanol outbreak in Norway 2002–2004: epidemiology, clinical features and prognostic signs. J Intern Med. 2005;258(2):181–190. | |

Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Pajoumand A, Dadgar SM, Shadnia Sh. Prognostic factors in methanol poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26(7):583–586. | |

Paasma R, Hovda KE, Tikkerberi A, Jacobsen D. Methanol mass poisoning in Estonia: outbreak in 154 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(2):152–157. | |

Brahmi N, Blel Y, Abidi N, et al. Methanol poisoning in Tunisia: report of 16 cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(6):717–720. | |

Davis LE, Hudson D, Benson BE, Jones Easom LA, Coleman JK. Methanol poisoning exposures in the United States: 1993–1998. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40(4):499–505. | |

Jacobsen D, McMartin KE. Methanol and ethylene glycol poisonings. Mechanism of toxicity, clinical course, diagnosis and treatment. Med Toxicol. 1986;1(5):309–334. | |

Sejersted OM, Jacobsen D, Ovrebø S, Jansen H. Formate concen- trations in plasma from patients poisoned with methanol. Acta Med Scand. 1983;213(2):105–110. | |

Nicholls P. Formate as an inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;67(2):610–616. | |

Bennett IL Jr, Cary FH, Mitchell GL Jr, Cooper MN. Acute methyl alcohol poisoning: a review based on experiences in an outbreak of 323 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1953;32(4):431–463. | |

Pappas SC, Silverman M. Treatment of methanol poisoning with ethanol and hemodialysis. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;126(12):1391–1394. | |

Wallage HR, Watterson JH. Formic acid and methanol concentrations in death investigations. J Anal Toxicol. 2008;32(3):241–247. | |

Kavet R, Nauss KM. The toxicity of inhaled methanol vapors. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1990;21(1):21–50. | |

Verhelst D, Moulin P, Haufroid V, Wittebole X, Jadoul M, Hantson P. Acute renal injury following methanol poisoning: analysis of a case series. Int J Toxicol. 2004;23(4):267–273. | |

Coulter CV, Farquhar SE, McSherry CM, Isbister GK, Duffull SB. Methanol and ethylene glycol acute poisonings – predictors of mortality. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(10):900–906. | |

Rzepecki J, Krakowiak A, Fiszer M, et al. [Acute methanol poisoning among patients of Toxicology Unit, Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine in Łódz, during the period 2000–2009]. Przegl Lek. 2012;69(8):431–434. Polish. | |

Paasma R, Hovda KE, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, et al. Risk factors related to poor outcome after methanol poisoning and the relation between outcome and antidotes – a multicenter study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50(9):823–831. | |

Vale JA, Kulig K; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. Position paper: gastric lavage. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(7):933–943. | |

Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP, Vale JA; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. Position paper: Single-dose activated charcoal. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43(2):61–87. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.