Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 12

Restructuring of Academic Tracks to Create Successful Career Paths for the Faculty of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences

Authors Wieder R , Carson JL , Strom BL

Received 12 May 2020

Accepted for publication 18 August 2020

Published 14 October 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 103—115

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S262351

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Robert Wieder,1,2 Jeffrey L Carson,2,3 Brian L Strom2

1Department of Medicine, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, USA; 2Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, USA; 3Department of Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA

Correspondence: Robert Wieder

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, 205 South Orange Avenue Cancer Center H1296, Newark, NJ 07103, USA

Tel +1 973-972-4871

Fax +1 973-972-2668

Email [email protected]

Background: We report faculty affairs lessons from the formation and academic restructuring of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences. Our approach may be a blueprint for development of a new track system that can be adapted by other institutions, after consideration of their own special circumstances.

Methods: We created new Appointments and Promotions guidelines consisting of one Tenure Track and four Non-Tenure Tracks, each with different missions. We restructured faculty performance evaluations to include mission-based criteria, an expanded rating scale, and specific expectations. After negotiating these new processes with our faculty union, we enacted central oversight to ensure uniform application of these processes and their associated criteria. We communicated the guidelines and the evaluation system widely. We created programs for universal mentoring, publishing education, diversity, and faculty development.

Results: All faculty in our seven schools went through track selection. Anxiety and incomplete understanding improved after implementation. Evaluations with expectations for the following year and an expanded scale for more nuanced assessment served as mentoring tools. Requirements for mentor assignments and diversity education created an atmosphere of nurturing and inclusion. Publications, extramural support, and faculty satisfaction increased after implementation of the guidelines.

Conclusion: Lessons included the need to review and learn from guidelines at other institutions, to create tracks that align with different jobs, the necessity for central oversight for uniform application of criteria, the need for extensive and frequent communication with faculty, and that fear of change is only reduced after evidence of success of a new structure. The most important lesson was that faculty rise to expectations when clear, ambitious criteria are delineated and universally applied.

Keywords: academic restructuring, faculty tracks, faculty development, faculty mentoring, faculty evaluations, faculty diversity

Background

Academic institutions occasionally face a need to revise the structure of their academic tracks to more appropriately serve the needs of the institution and to support their faculty’s ability to succeed; this is especially likely, although not uniquely so, after a restructuring. Although the driving forces and circumstances are unique in each situation, there is little guidance available on general approaches and considerations in carrying out changes in a faculty track system. Yet, faculty are a university’s core asset. A number of reports have shed light on relevant considerations of academic tracks governing clinical educators in the health sciences, but most were focused solely on medical schools.1–8 We describe the driving forces and structural details of creating Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences (RBHS), which included eight health care professional schools with historically highly divergent scholarly, educational, and clinical missions. We also describe our rationale, approach, and outcomes for development of a new academic track system that provides opportunity for our diverse faculty to succeed. Our experience can serve as a general guide to a wide range of institutions intent on restructuring their academic tracks and improving the success and productivity of their faculty.

Restructuring of New Jersey Universities

The driving force for this specific endeavor arose from political efforts to improve higher education in our state. In 2012, two of the largest public universities were Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ), the largest freestanding health sciences university in the United States. A report by a commission tasked by the Governor to assess medical and allied health care education in the state reported that the quality of higher education in the state needed improvement.9 A series of blue-ribbon panels had proposed a range of configurations for a merged entity.9–12 In July 2013, the New Jersey Medical and Health Sciences Education Restructuring Act New Jersey Statutes Annotated (N.J.S.A.) 18A:64M-1, et seq. incorporated most of the schools, centers, and institutes of UMDNJ into Rutgers.13 The final structure of the integrated University consisted of four chancellor units: Rutgers-New Brunswick (RU-NB), Rutgers-Newark (RU-N), Rutgers-Camden (RU-C), and RBHS, the latter including most of the former UMDNJ units as well as health-related units from legacy Rutgers (see Figure 1). The legacy Rutgers University and formerly UMDNJ faculty were and continue to be represented by different faculty unions for collective negotiations.

The newly formed RBHS consists of seven primary schools (Figure 1). They are the New Jersey Medical School (NJMS), the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (RWJMS), the School of Dental Medicine (SDM), the School of Nursing (SON), the School of Health Professions (SHP), the Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy (EMSOP), and the School of Public Health (SPH). NJMS, RWJMS, SDM, SHP (formerly the School of Health Related Professions), and SPH were originally UMDNJ schools. EMSOP was originally a Rutgers school. The SON was formed from the merger of the Rutgers College of Nursing (CON) and the UMDNJ School of Nursing.

In addition, the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, formerly a UMDNJ school, initially became a school within RBHS but was later merged with the former Rutgers Graduate School - New Brunswick, to form a single Rutgers School of Graduate Studies, reporting jointly to the Chancellors of Rutgers-New Brunswick and RBHS. Five UMDNJ or Rutgers Institutes, including the Cancer Institute of New Jersey (CINJ), the only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in New Jersey, and the very large University Behavioral Health Care, also moved into RBHS. Two additional chancellor-level institutes were created later, the Brain Health Institute and the Institute for Translational Medicine and Science. Faculty in institutes and the Graduate School held their primary academic appointments in one of the other Rutgers schools. The former UMDNJ School of Medicine (Osteopathic) (SOM) in Camden was transferred to Rowan University. UMDNJ’s University Hospital (UH) in Newark became a standalone state hospital, with a continuing mission to serve as the principal teaching hospital for Newark-based RBHS schools and to provide health care to the underserved communities of Newark and Essex County.

The Legacy Academic Track Systems

Approximately 85% of faculty in the historical pre-merger Rutgers University are tenured or on Tenure Track. The remaining full-time faculty are on the Non-Tenure Track and have term contracts. Switching between tracks is not permitted. Tenure can only be obtained on the Tenure Track and faculty have 6 years to obtain tenure or they have to leave the University. The tenure process is uniformly rigorous and is adjudicated by the department, school appointments and promotions committee, the Dean, a University-wide Promotions Review Committee, and the Board of Governors.

The prior UMDNJ system consisted of a Tenure Track and a Non-Tenure Track. There were no up-or-out provisions and guidelines permitted unrestricted switching between the Tenure Track and the Non-Tenure Track. Tenure could be achieved on investigational, clinical, or teaching pathways and the criteria and rigor of their application varied considerably among schools, even between the two medical schools. Scholarship requirements on the Non-Tenure Track also varied among schools. Faculty whose career was mostly clinical had difficulty ever getting promoted, while faculty who were researchers could seek and obtain tenure, even decades after starting on faculty. There was no central oversight and school decisions were rarely reversed at the University level.

Rationale for Restructuring Academic Track Systems

Historical assessments of health care educator faculty tracks underscore the complicated balance among fulfilling scholarly, clinical, and teaching obligations while ensuring equal stature, opportunities for success, and for career advancement among faculty with different career trajectories.3,4,14,15 Nationwide, there is great diversity, reported mostly in medical schools, among the structure of track systems to accommodate this, and their approach to balancing academic and clinical duties and pathways to success.8 Problems have arisen on scholarly tracks, including disparities among clinical faculty with lighter clinical duties, who tended to be of higher rank3 and were promoted sooner14 than more clinically encumbered faculty. This has led to dissatisfaction and high turnover.15 An uneasy choice exists between applying equally stringent standards of scholarship to academic clinicians with low vs high amounts of clinical responsibility using a single track system and the creation of multiple tracks that perhaps lead to the perception of “second-class” status of primarily clinical track members.4 Fortunately, the latter concern has abated somewhat in more recent years as respect for non-tenure tracks in US medical schools has improved.5 The effectiveness of various systems has been further complicated by lack of central oversight, exemplified by systems where the requirements for scholarship on the same track were applied differently among different schools within the same university system,2 and by highly liberal and diverse policies permitting switching between tracks among US medical schools.1

Goals of Restructuring the RBHS Academic Track System

We undertook the challenging task of creating a track system that served all seven professional schools and their multiple diverse missions. We set out to incorporate the above lessons from the literature to design a structural framework where all faculty had equal opportunities to succeed. In addition to restructuring academic tracks and appointments and promotions processes within RBHS, leadership had to undertake initiatives to foster success. Given a situation with widely divergent faculty advancement standards and historically varied emphasis on scholarship among the seven health care professions schools that ultimately constituted RBHS, our goals were to change the culture to one of high standards, clear expectations, and multiple paths to success. Our approach involved communicating these changes and providing oversight, career guidance, career development and continued positive reinforcement. This approach will have potentially wide application to many academic healthcare institutions aspiring to unify excellence among varied schools.

Methods

Restructuring the RBHS Academic Track Systems

Immediately upon appointment in January 2014, the two provosts – one from the RBHS New Brunswick Campus and one from the RBHS Newark Campus, as mandated by the Restructuring Act13 – were tasked with restructuring and overseeing the academic affairs of the seven RBHS schools holding the primary faculty appointments. The goal was to create uniform, high standards, and a system that provided opportunities for all faculty to succeed. The aim was to stay close to legacy Rutgers processes, while recognizing our differences as a healthcare entity. Our vision was to create a system with unique tracks, where each track was a different job that fit the career goals of each faculty member. The common elements of the tracks were scholarship, clinical excellence, teaching, and service, but with different priorities, attributes, and emphases in each track, reflecting the different career paths. Professionalism was an expectation for all faculty.

The provosts studied examples of promotions guidelines from Rutgers, the UMDNJ schools, and nineteen other top universities and health sciences systems. We applied lessons learned from a wide variety of structures and applications of Tenure and Non-Tenure academic tracks of US medical and other health sciences schools, all individually designed to serve the specific needs of each institution.1–8 After extensive discussions and multiple iterations, we generated new guidelines, following the Tenure Track and Non-Tenure Track titles and regulations already in place at Rutgers, modified to suit the special needs of healthcare faculty.

As noted, all full-time faculty who were not administrators were represented by faculty unions. In this setting, we could not engage in direct discussions with faculty regarding proposed tracks due to rules against direct dealing. In writing the guidelines, we were able to make changes in academic criteria but we had to either keep existing processes or negotiate with unions any changes in processes. We introduced the new set of Appointments and Promotions (A&P) Guidelines that embodied our vision in contract negotiations, along with all other labor matters. The A&P Guidelines were approved in November, 2015 as part of a comprehensive labor agreement between Rutgers and the American Association of University Professors-Biomedical and Health Sciences of New Jersey (AAUP-BHSNJ), the bargaining unit now representing the majority of the former UMDNJ faculty.16 No changes were made for EMSOP and half of the SON, who were covered by the traditional Rutgers faculty union. In an environment which is not as heavily unionized, such discussions would presumably need to be held with groups of faculty.

Dissemination

After ratification of the agreement with AAUP-BHSNJ, the provosts conducted 23 presentations in general campus-wide and individual school town halls, to chairs in individual schools, Appointments and Promotions Committees, and faculty affairs administrators, to disseminate the content, intent, and application of the tracks and guidelines. We posted the videotaped presentations on the Faculty Affairs website for convenient access. We also presented the guidelines to individual departments when requested and responded individually to queries from chairs, division chiefs, program directors, and faculty members, both in formal meetings and informally by telephone, email, or hallway conversations. We assisted faculty holding ≥50% appointments through a track selection process which ended June 30, 2016. Faculty who had been on the Tenure Track for more than nine years prior to ratification of the revised system, particularly if they had been promoted to Associate Professor not yet tenured, were strongly encouraged to switch to one of the Non-Tenure Tracks during this one-time period of opportunity or during a one-year grace period that followed, when leadership considered requests for track switching. This advice favored faculty in this category, as the likelihood of success in achieving tenure under the new criteria after years of a non-promising trajectory on the Tenure-Track was low. After the track selection deadline, the provosts continued the aggressive communications and education program in all of the schools at all levels.

Academic Oversight

We instituted oversight over the track selection implementation process to improve understanding and ensure consistent application of the guidelines across the seven schools of RBHS. For prospective faculty, we required that every offer letter be approved by one of the provosts to ensure that an effective national search was conducted, that reference letters and the curriculum vitae supported the candidate’s suitability for the position and track selected, that a mentor was designated for every faculty recruit at the rank of Assistant Professor or lower, and that appropriate research start-up resources were provided for Tenure Track faculty. An electronic databank of all faculty actions was generated by the RBHS Faculty Affairs Office, accessible to all administrative offices involved in faculty onboarding, the provosts, and chancellor. When a faculty file was ready for provost approval, an automatic notification was emailed to the provosts. Once both approved it, it moved forward to the chancellor for approval.

The provosts and the chancellor began to review and approve all appointments, promotions without tenure, and reappointments on the Tenure Track. Actions that were not tenure significant and did not meet the A&P Guidelines criteria were rejected, even if school-approved. Awards of tenure or promotions with tenure went from internal recommendations in the school, as outlined above, directly to the Rutgers Promotions Review Committee and the Board of Governors to ensure uniformity in application of criteria throughout the university, in line with Rutgers University processes.

We instituted Tenure Track review in the last year of a faculty member’s contract prior to its renewal, to provide expert assessment early on. The review was instituted to identify faculty who are not on a successful trajectory, informing them early if the path to tenure is unlikely, and allowing them to pursue career options elsewhere. In more promising situations, Tenure Track review permits early mentoring and course correction to a successful trajectory.

The evaluation system we chose to replace was as divergent as the criteria for promotion, requirements for scholarship, and historical expectations of faculty achievements among the seven schools. We adapted faculty performance evaluations to become more effective improvement tools. Historically, there were three gradings: “unsatisfactory”, “meets expectations”, and “exemplary”. The grade of “unsatisfactory” was given out exceptionally rarely, despite clear failures of expectations and, more frequently than not, the grade of “exemplary” was awarded despite lack of evidence of exceptional achievement in the mission areas of the faculty members. We charged three committees to generate specific examples of criteria in the clinical, teaching, and service mission areas; scholarship criteria are well established in academia and did not need a committee. We adopted a five-point scale, specifically to permit awarding of the grade “needs improvement” without having to provide an “unsatisfactory” rating and, conversely, to permit the use of “exceeds expectations” in cases where performance did not achieve “exemplary” levels. This powerful mentoring tool permits evaluations to be meaningful, to identify and correct weaknesses in a positive, guiding interaction between a supervisor and a faculty member, and to recognize better than average performance when it does not achieve exemplary heights. The evaluation also requires specific effort distribution and mission-based goals for the subsequent year as guides to expected performance.

Faculty Development

We created an extensive faculty development program to optimize chances for success. We hypothesized that these measures would generate positive results in faculty satisfaction, academic success, and rates of career advancement.

The provosts charged a committee representing all schools and institutes to create an RBHS-wide faculty mentoring program, generate faculty development programs, and recommend outcomes metrics. We held annual mentoring symposia and symposia on scholarly publishing. We created a committee to evaluate and promote faculty development across RBHS. At their recommendation, the provosts appointed a Vice-Chancellor for Faculty Development. RBHS created a training program for chairs and other leaders. The medical schools have also sponsored faculty for the American Association of Medical Colleges leadership training program. In addition, we sponsored faculty to attend the highly selective Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program. RBHS sponsored faculty from any school to attend the yearly Higher Education Resource Services Leadership Training Program (HERS) training programs, as well as the Rutgers Leadership Academy.

We also created a committee to evaluate and promote diversity in RBHS faculty. At their recommendation, we opened a nationwide search and appointed a Vice-Chancellor for Diversity and Inclusion, tasked with implementing their comprehensive recommendations and to position RBHS as a national leader in creating a successful diverse faculty. Both the Rutgers University President’s Office and the RBHS Chancellor created programs to support recruitment of diverse faculty on both Tenure Track and Non-Tenure Tracks.

Process Evaluation

We obtained extensive qualitative feedback regarding the level of comprehension of the system directly from faculty at town hall meetings and individual encounters, at chair meetings in each of the schools, and at our annual leadership retreat. Quantitatively, we tabulated the number and percentage of faculty in each school who selected the Tenure Track and the various Non-Tenure Tracks. We examined the track selection distributions among the schools and compared them with their historical academic characteristics. We compared the academic rank of faculty who were on Tenure Track, not yet tenured before track selection with the percentage of these faculty who chose to remain on Tenure Track.

Outcomes Evaluation

We obtained quantitative data on two faculty productivity variables as metrics after track selection by the faculty: publications and extramural grant support. Publication numbers were generated by the Rutgers Health Sciences Libraries using PubMed Annual searches. Authors across all RBHS schools were counted and updated quarterly. Unique publications, including manuscripts listed in NLM Epub Ahead of Print, were included. We also compiled data generated annually by the Rutgers University Office of Research and Economic Development on extramural grant support and indirect costs from federal and state awards and foundation and corporate contracts.

Results

The New RBHS Academic Track System

The new A&P Guidelines established 5 tracks: one Tenure Track and four Non-Tenure Tracks (Table 1).16 Among the Non-Tenure Tracks, the Clinical Track, Teaching Track, and Research Track required scholarship, while the Professional Practice Track did not. Tracks represent different jobs and have equal importance and value. To underscore this fact and allay concerns raised in the literature,4 faculty on all tracks have full academic titles without qualifiers. There is no up-or-out provision on any of the tracks except the Tenure Track. Two pre-track titles, RBHS Instructor and RBHS Lecturer, also have up-or-out provisions, primarily to protect faculty from stagnation. Faculty can be part-time RBHS Lecturers indefinitely, however.

|

Table 1 Criteria and Characteristics for Pre-Tracks and Tracks for RBHS Faculty |

Tenure can only be obtained on the Tenure Track and is awarded for successfully leading a field of investigation, including securing substantial and sustained peer-reviewed funding. Faculty have nine years to obtain tenure but must undergo rigorous reappointment reviews every three years. The nine-year term recognizes the competing time demands for faculty with part-time clinical responsibilities, as well as the longer time needed for health care investigations to yield extramural funding, results, impactful publications, and renewed funding compared to non-health sciences investigations. Our tenure evaluation process largely follows the traditional Rutgers process, other than the longer tenure probationary period and clearer requirements for extramural funding.

The Clinical Track and the Professional Practice Track are intended for faculty who primarily spend their time providing healthcare. The Clinical Track is divided into the Clinical Scholar and Clinical Educator pathways. Both require significant scholarly productivity, but the Clinical Scholars are required to conduct collaborative, extramurally supported research, although they need not lead the research. The Professional Practice Track provides clinical faculty who spend all their time in clinical activities and teaching with an opportunity for promotion based primarily on clinical excellence and reputation.

The Teaching Track also requires substantial scholarship, usually in publications about their educational initiatives. These faculty members have careers in teaching but are expected to lead their fields through their scholarship.

The Research Track is designed for faculty who engage primarily in investigation but do not normally lead these investigations. They work on other investigators’ research, supported by their principal investigators’ grants or by core facilities, where they are a source of collaboration and expertise for other investigators.

RBHS Lecturers and RBHS Instructors are not yet in a track. Most RBHS Lecturers do not have terminal degrees but are expected to complete one in 9 years or receive a terminal one-year appointment. RBHS Instructors have terminal degrees and have three years before they must be promoted to Assistant Professor on one of the tracks or they receive a terminal one-year appointment. This title can be used for potential Tenure Track investigators who do not yet have a career development award or as an entry to one of the Non-Tenure Tracks for faculty who do not yet have accomplishments needed to be promoted to Assistant Professor.

Effectiveness of the Dissemination Processes

When the time for track selection came around, there was a great deal of apprehension, angst, and career trepidation among faculty. The two main points of confusion in the track selection process were the choices clinicians had to make among the three pathways and the decision to remain on Tenure Track for those not yet tenured. The extensive communications were only partially effective in allaying all of their fears and conveying a complete understanding of the different jobs that the different tracks defined. Only after implementation and track selection, there began to emerge a greater understanding of the nuances of the track each faculty member selected and the possibility that perhaps another track would have been more appropriate. We continued to consider requests for track switching for one year after the track selection date, to account for the lack of understanding at the time of switching.

Results of the Track Selection Process

A total of 1611 faculty who were ≥0.5 full time equivalents (FTE) in seven schools selected tracks by July 2016 (Figure 2). The distribution varied widely among the schools. The following highlights some of the notable trends.

Clinical practitioners in NJMS selected the Clinical Scholar pathway (3.7%), the Clinical Educator pathway (42.5%), and the Professional Practice Track (53.8%) at similar rates as practitioners in SDM (8.3%, 41.2%, and 51.5%, respectively) (chi square p = 0.21). In contrast, practitioners at RWJMS selected the Professional Practice Track far less frequently than practitioners at NJMS (16.9%, 46.1%, and 37.0% for the three clinical pathways, respectively) (chi square p < 0.001). A small number of clinical faculty opted to change their tracks from Clinical Educator to Professional Practice during the one-year grace period after the track selection deadline after coming to understand the requirements only after the institution of the new track system, despite the extensive messaging prior to initial track selection.

SON and SHP used predominantly the Teaching Track. NJMS had the highest rate of use of the Research Track, reflecting its highest rate of extramural funding and historical research strength among the RBHS schools. Overall, RBHS had about 20% tenured faculty, with the highest rates in SPH and EMSOP and lowest rates in SHP, SDM, and SON. About 5% of the RBHS faculty were on Tenure Track, not yet tenured, with much lower rates in SDM and SHP, reflective of the relative lack of a substantial extramurally funded research tradition in those schools. Similarly, faculty from legacy Rutgers CON had much higher rates of Tenure Track faculty, not yet tenured, than legacy UMDNJ SON, again reflecting differences in the history of scholarship in the two schools, as well as the predominant use of the Tenure Track in the legacy Rutgers schools.

Overall, 52% of faculty on Tenure Track not yet tenured in the legacy UMDNJ schools elected to remain on Tenure Track. Of these faculty, 63% still at the Assistant Professor level opted to remain on Tenure Track, while only 36% of faculty at the rank of Associate Professor or Professor level, not yet tenured, elected to remain on Tenure Track (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Rates of RBHS Tenure Track Selection Among the Legacy UMDNJ Faculty |

The success rate for promotions and awards of tenure in the first year after the new tracks were applied was 83%. Once a round of successful promotions took place in the year after track selection, some of the fears began to dissipate. At our first ever reception for faculty promoted that year, faculty thanked us for the new system.

Metrics and Achievements Under the New Track System

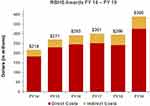

We analyzed two metrics indicative of academic success that were easily obtainable and are generally recognized as reflective of academic success of an academic institution: indexed publications and extramural research funding; both demonstrated immediate improvements. PubMed-indexed RBHS faculty publications increased by 77% from FY 2014 to 2019 (Table 3). Extramural funding for basic and clinical research and outreach programs increased by 79% from 2014 to 2019 (Figure 3).

|

Table 3 RBHS Annual Faculty Publications Listed in PubMed |

|

Figure 3 RBHS extramural support data that included federal and state awards and foundation and corporate contracts. Total costs increased 79% from FY-14 to FY-19. |

We had some additional successes. Our faculty leadership training programs have resulted in meaningful impacts on the careers of the trainees. Greater than 80% of our graduates of these programs have assumed leadership roles and made significant impacts in RBHS programs. In 2019, RBHS was awarded a competitive National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award (neither Rutgers nor UMDNJ had previously applied for one itself) and the Cancer Institute’s Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant from the National Cancer Institute was renewed. The School of Health Professions achieved the number 1 ranking in College Factual’s Best Colleges to study Health Professions.

Discussion

Our efforts resulted in the creation of a unified faculty Appointments and Promotions system for the newly formed RBHS with one Tenure Track and four Non-Tenure tracks that defined distinctly different jobs for all faculty members, permitting each to succeed in their chosen track. We conducted an extensive education and dissemination program, fostered faculty through the track selection process and instituted a series of initiatives for faculty success. The process had immediate positive effects including ones on two metrics, publications and extramural support. Tracking metrics at such an early time after track selection are obviously limited but show a clear direction toward improvement in the quality of the institution. More formalized tracking of additional academic variables over time will provide a clear picture of the significant effects of the new track system on faculty successes and the status of the institution.

The level of comprehension of the track requirements by faculty and supervisors remains incomplete to this time but has improved with continued education and application. The greatest change in the level of comprehension and fear occurred between the time when the tracks were an abstraction and the time when faculty had to select a track. The latter was the time they had to understand track-specific criteria that matched their own circumstance to optimize their career path to success. This is in line with the human capacity to deal with fear of change only when they perceive that they are equipped to handle the change.17

The differences in the distribution in the two medical schools of the selection patterns between the two clinical tracks and their three pathways either requiring or not requiring scholarship reflected an example of pre-existing conceptions by the faculty that were difficult to overcome. Some faculty and chairs felt that a Medical School faculty member should not be in a track named Professional Practice. This occurred despite the extensive messaging that all titles would be the same, without qualifiers, as noted above. The one-year grace period when we considered track switching provided a welcome opportunity to faculty to switch to the track that best defined their career path based primarily on considerations of criteria rather than preconceived impressions.

The messaging for selection of Tenure Track was more effective. Faculty who had been on Tenure Track but not yet tenured after being promoted to Associate Professor understood that their trajectory would not achieve them tenure in the additional years the guidelines provided after track selection and that they would have to leave the University. As noted, 64% selected one of the Non-Tenure tracks. However, some insisted on remaining on the Tenure Track despite advice to the contrary. Their outcomes remain to be determined in the next few years.

To improve the success of our communications, a potential alternative approach may be to generate a teaching tool consisting of a series of artificial scenarios with variable fictitious faculty credentials to use during instructional sessions. However, this may portray cookie cutter examples that will not apply to real individuals. Requirements are general and individual curricula vitae are unique. Leaders must be cautious in presenting specific scenarios, as they can be misinterpreted as checklists for promotion. While we presented to chairs in every school and communicated with them informally whenever they reached out to the provosts, it may have been useful to spend additional time to instruct them on comprehending the guidelines in additional formal training sessions, as they are the ones initiating faculty actions. This would also serve to expose faculty to additional repetitions of the presentation, an acknowledged learning tool. Overall, our communications in the future must convey the understanding that change, while in principle can be uncomfortable, will bring benefits for the faculty.17 It may also be useful for anyone undertaking such changes in the future to assess the effectiveness of communication quantitatively and elicit commentary on potential improvements formally through surveys.

The small percentage of promotions that were not approved after review by the Provosts and the Chancellor served as educational tools for both school leadership and for the faculty as to the clear expectations required by the new guidelines. Faculty, together with leadership, endeavored to develop success in achieving the requirements for successful promotion and chairs and school leadership began to consult with the provosts to understand criteria for promotions in specific tracks on a routine basis. Similarly, awards of tenure and promotions with tenure now were adjudicated at the University level by the Promotions Review Committee, where uniform criteria are applied. School and Department leadership quickly understood those criteria and faculty who were either not on an appropriate trajectory or did not meet criteria were no longer proposed. The increased successes in the academic metrics we delineated are clear examples of increased endeavors by faculty to fulfill the requirements of their chosen tracks.

The implementation of change in any institution is a daunting task. It is always faced with trepidation, resistance, and lack of understanding, or sometimes perhaps, a lack of will to understand. Faculty at health sciences institutions as well as faculty in all institutions are intelligent, highly trained, and experienced. Yet, the human fear of change prevails. We have learned a great deal in instituting a new faculty track system and oversight across our seven schools and continue to learn as we go on.

In evaluating the success of our communication efforts, we have generated a few takeaways. The primary lesson is that comprehensive, ongoing, relentless, and continuing communication is a must for any change to be understood and accepted. It is the job of administration to convey a vision and an understanding of the goals of a new system, the nuances of its function, and the benefits it will bring to each faculty member. It is also the role of the administration to advise faculty and supervisors on global as well as specific application of a new system. Eventually, with experience in application, criteria for promotion will become clear to the majority of faculty and supervisors.

Conclusions

We learned a number of lessons from creating and implementing the guidelines (Table 4). We learned that: 1) When creating guidelines, leadership must review the broad spectrum of existing guidelines of aspirational institutions and schools. They must consider local constraints such as track names, historical differences among their schools and their fields of discipline, and the presence of bargaining units. 2) The specific tracks they create must represent distinct and different jobs that will permit all faculty to select a track that serves as a conduit for their success and therefore there will be no need to switch tracks. 3) Leadership must institute central oversight to ensure uniform application of criteria and standards in all schools in the system. 4) They must negotiate parts of the document that need negotiating with existing bargaining units. 5) Educating the faculty and their supervisors regarding new guidelines must be a continuous and frequent part of leadership’s efforts. 6) We also learned that, regardless of the extent of communication, faculty, supervisors and administrators only begin to understand the criteria for success only after the new A&P Guidelines are implemented. The fear of change significantly impacts faculty. Initial resistance, fear, complaints, and lack of understanding of new tracks and criteria only abate after a round of successful promotions. 7) Clear and uniformly applied expectations provide a sense of comfort and job satisfaction. However, perhaps the most important lesson was that 8) faculty rise to the occasion when clear criteria and expectations are established and enforcement and oversight are applied evenly. Clear expectations create a sense of comfort that permits faculty to articulate their aspirations and expect that if they meet or exceed them, they will be rewarded. As our initial metrics suggest, 9) the key to success of a university is the success of its faculty.

|

Table 4 Description of Lessons Learned from Restructuring of Faculty Track System |

Abbreviations

A&P, Appointments and Promotions; AAUP-BHSNJ, American Association of University Professors-Biomedical and Health Sciences of New Jersey; CINJ, Cancer Institute of New Jersey; CON, Rutgers College of Nursing; ELAM, Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine; EMSOP, Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy; HERS, Higher Education Resource Services; NJMS, New Jersey Medical School; N.J.S.A., New Jersey Statutes Annotated; RBHS, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences; RU-C, Rutgers-Camden; RU-N, Rutgers-Newark; RU-NB, Rutgers-New Brunswick; RWJMS, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School; SDM, School of Dental Medicine; SHP, School of Health Professions; SOM, UMDNJ School of Medicine (Osteopathic); SON, RBHS School of Nursing; SPH, School of Public Health; UH, University Hospital in Newark; UMDNJ, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

N/A

Consent for Publication

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Muller of the RBHS Faculty Affairs Office for providing faculty track selection data, Judy Cohn, Sarah Jewell and Yingting Zhang of the Rutgers University Libraries for providing publications data, Edward Nonnenmacher, Neil Grant and Steven Andreassen for providing grants data and Lisa Bonick for reviewing the manuscript.

Authors’ Information

– Robert Wieder, MD, PhD is Professor of Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and was inaugural Provost of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences – Newark until July 2018.

– Jeffrey L. Carson, MD is a Distinguished Professor of Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and is inaugural Provost of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences – New Brunswick.

– Brian L. Strom, MD, MPH is University Professor and inaugural Chancellor of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and Executive Vice President for Health Affairs, Rutgers University.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No extramural funding sources were used to produce the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no competing interests for this work.

References

1. Hunt RJ, Gray CF. Faculty appointment policies and tracks in U.S. dental schools with clinical or research emphases. J Dental Educ. 2002;66(9):1038–1043. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2002.66.9.tb03571.x

2. Howell LP, Bertakis KD. Clinical faculty tracks and academic success at the University of California Medical Schools. Acad Med. 2004;79(3):250–257. doi:10.1097/00001888-200403000-00012

3. Thomas PA, Diener-West M, Canto MI, Martin DR, Post WS, Streiff MB. Results of an academic promotion and career path survey of Faculty at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2004;79(3):258–264. doi:10.1097/00001888-200403000-00013

4. Fleming VM, Schindler N, Martin GJ, DaRosa DA. Separate and equitable promotion tracks for clinician-educators. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1101–1104. doi:10.1001/jama.294.9.1101

5. Bachrach DJ. Non-tenure tracks now more respected. Acad Phys Sci. 2006.

6. Bunton SA, Mallon WT. The continued evolution of faculty appointment and tenure policies at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):281–289. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180307e87

7. Todisco A, Souza RF, Gores GJ. Trains, tracks, and promotion in an academic medical center. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1545–1548. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.016

8. Coleman MM, Richard GV. Faculty career tracks at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):932–937. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182222699

9. Vagelos PR, Campbell RE, Coleman BB, et al. The report of the New Jersey Commission on Health Science, Education, and Training 2002.. Available from: http://oirap.rutgers.edu/msa/documents/hset.pdf.

10. Vagelos PR. New Jersey System of Public Research Universities draft final report. 2004. Available from: https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=vagelos+report.

11. Keane TH, Campbell RE, Howard M, McGoldrick JL, Pruitt GA 2010. The report of the Governor’s Task Force on higher education. Available from: http://www.state.nj.us/highereducation/documents/GovernorsHETaskForceReport.pdf.

12. Barer SJ, Campbell RE, Harley JW, Perno III AJ, Shapiro HT 2012. The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Advisory Committee final report. Available from: http://www.rowan.edu/president/downloads/UMDNJ%20Advisory%20Committee%20Final%20Report.pdf.

13. The New Jersey Medical and Health Sciences Education Restructuring Act. NJ Bill A-3102/S-2063. 2012. Available from: https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2012/bills/a3500/3102_r2.htm.

14. Levinson W, Rubenstein A. Mission critical–integrating clinician-educators into academic medical centers. New Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):840–843. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909093411111

15. Buckley LM, Sanders K, Shih M, Hampton CL. Attitudes of clinical faculty about career progress, career success and recognition, and commitment to academic medicine. Results of a survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2625–2629. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.17.2625

16. A&P Guidelines. November 2, 2015. Available from: http://rbhs.rutgers.edu/appointments.shtml.

17. Gonçalves JM, Pereira da Silva Gonçalves R. Overcoming resistance to changes in information technology organizations. Procedia Technol. 2012;5:293–301. doi:10.1016/j.protcy.2012.09.032

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.