Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

Psychological literacy: proceed with caution, construction ahead

Authors Murdoch D

Received 10 March 2016

Accepted for publication 19 May 2016

Published 8 August 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 189—199

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S88646

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Douglas D Murdoch

Department of Psychology, Mount Royal University, Calgary, AB, Canada

Abstract: Psychological literacy is the ethical application of psychological skills and knowledge. This could benefit individuals in their personal, occupational, and civic lives and subsequently benefit society as a whole. We know that psychology has a wide-ranging impact on society. The potential benefits of a psychologically literate citizenry in improved parenting, better business practices, enlightened legislation, and many other areas make this a desirable goal. It has been proposed that this should become the primary goal of an undergraduate psychology education to benefit the majority who do not go on to graduate school and even those who only take a few psychology courses. This idea has significant merit and warrants further investigation and development. However, there are major concerns that need to be addressed. First, what are uniquely psychological skills and knowledge? Many of the skills psychology undergraduates acquire are generic to university and not specific to psychology. Second, psychology can be as harmful when misapplied as it can be beneficial when ethically applied. Third, psychology departments will need to address pragmatic as well as ethical issues, including issues of competency, boundaries, accountability, and confidentiality. Fourth, the available empirical evidence to direct such efforts is primarily at the anecdotal, case example, and pilot study stages. Significant improvements are needed in measuring psychological literacy, choice of outcome measures, and research methodologies before these advantages can be realized in an empirically supported manner. Currently, best practices in the undergraduate curriculum are the mindful and purposeful design of courses and experiential opportunities. It is proposed that psychological literacy is best conceptualized as a meta-literacy and that it should become a goal of psychology undergraduate education but not necessarily the goal.

Keywords: teaching of psychology, best practices, undergraduate psychology, ethics, psychology’s uniqueness, curriculum, student learning outcomes

Introduction

Psychological literacy is “the general capacity to adaptively and intentionally apply psychology to meet personal, professional and societal needs.”1 This is not a new idea. Miller2 stated that “everyone practices psychology, just as everyone who cooks is a chemist” and that psychology should “teach them to practice it better, to make use self-consciously of what we believe to be scientifically valid principles.” However, it is clear that Miller’s vision has never been fulfilled to the extent it could be. It is now being proposed that psychological literacy should be the primary goal of a baccalaureate degree in psychology.1,3,4 This article contends that this is a laudable goal but that significant work needs to be performed and we must proceed with caution.

There is evidence for a pervasive and profound impact of psychology on society.5–7 A growing list of “Psychology Works Fact Sheets”8 includes mental health issues, the benefits of exercise, managing everyday stress, and conducting better job interviews among others. Increased occupational success and well-being can be found in the successful interventions of industrial/organizational psychologists. Sport psychologists enhance performance and personal well-being. The benefits of psychological knowledge and skills for individuals can be found in the successful outcomes of parent training programs, the human potential movement, and its successor, positive psychology. Recent systematic evaluation of the connection between disciplines has established psychology as a hub science – a scientific field of study that intersects with and informs multiple other fields.9,10 However, by and large, when we refer to the impact of psychology, we are referring to professional and academic psychology. The psychological literacy concept involves raising the impact of psychology through nonprofessionals and more specifically baccalaureate psychology students.

There are also numerous examples where a lack of psychological literacy is problematic. There are concerns that some professionals who provide mental health services lack sufficient psychological literacy, including family doctors,11–13 nurses,12,14 and social workers.12,15 Doctors also lack knowledge regarding behavioral medicine.16 Just as there has been concern with politicians’ lack of scientific literacy,17 concern has been expressed regarding their lack of psychological literacy.18,19 O’Hara20 notes the lack of psychological literacy demonstrated by reporters commenting on issues such as terrorism. Inaccurate and misguided psychological knowledge may be worse than a lack of psychological literacy.21,22 These are just a few examples where a small application of psychological literacy could significantly and positively impact the quality of life of a wide range of individuals. The impact of increased individual psychological literacy is potentially societal changing but currently is largely anecdotal.

The concept of psychological literacy, at least by that term, rarely appears outside of the psychology literature. One excellent exception is James23 who sees the benefits of psychological literacy for lawyers both professionally and personally, calling for the integration of psychological literacy into law curriculums. Similarly, Scherger24 and van den Heuvel et al25 call for medicine to integrate psychologists more fully into the health care system. A psychological, social, and biological foundations module was recently added to the Medical College Admission Test.26 These all signal the growing acknowledgment of the benefits of psychological literacy outside of psychology.

Definitional and conceptual issues

What is psychological literacy exactly? As a discipline and a profession, we need to answer the question: What makes psychology unique?12 What unique knowledge and skills distinguishes our students from other graduates?21 One problem is that psychology overlaps with many other disciplines and professions. In many jurisdictions, psychology has no exclusive scope of practice for this very reason.

Boneau27 equated psychological literacy with mastery of the core vocabulary of the discipline. The original meaning of literacy was simply “well educated, learned”28 so this simple straightforward understanding is appropriate. However, literacy has evolved to mean the skills associated with learning and their application in context, not just the content.28 McGovern et al29 provided a definition of psychological literacy more fitting this newer understanding of literacy, including the following elements:

- Understanding the basic concepts and principles of psychology

- Thinking critically

- Having problem-solving skills

- Understanding scientific research practices

- Communicating well in different contexts

- Applying psychological principles to personal, social, or organizational problems

- Acting ethically

- Having cultural competence and respecting diversity

- Having self and other awareness and understanding.

This conceptualization is problematic. On face validity alone, only abilities 1 and 6 are exclusively psychological. The development of critical thinking is an essential and a desirable goal for an undergraduate psychology program,30 but it is hardly unique to psychology. Most disciplines would rightfully claim this goal for their students. Similarly, it is laudable that psychology students should have respect for diversity, but hopefully this would be true for all university students. Abilities such as these may facilitate the application of psychological knowledge, but they are not in and of themselves psychological literacy. This has been confirmed by factor analysis of measures that captured these nine core features.21 It was found that most of the concepts fell under a single factor called “generic graduate attributes”. There was another factor called “reflective processes” entailing insight into others and the self, or in other words emotional intelligence. Only the third factor seemed to be uniquely psychological, “psychology as a helping profession”. These distinctions become important if we are to clarify for students and their future employers why psychology is an advantageous major. Statistical acumen, critical thinking skills, information literacy, communication skills, and others are all essential to the student learning outcome goals of undergraduate psychology, but they are not unique to psychology.

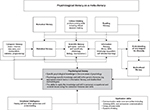

I contend therefore that psychological literacy is a meta-literacy: a higher order literacy that requires and incorporates other essential literacies. It involves the integration of reading, numeracy (statistics), scientific (methodology, physiology, biology, and neuroscience), information and data, computer, emotional intelligence, cultural, and multicultural literacies as well as psychology-specific knowledge. It requires the integration of multiple paradigms as well. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1. This model is conceptual not empirical. It is a refinement of the original McGovern et al’s29 definition by attempting to separate out the uniquely psychological aspects of psychological literacy from the important but non-psychological building blocks. It proposes that at its center, psychological literacy is the core knowledge of the profession and the psychology-specific aspects of the generic literacies with the added element of an emphasis on its applicability in everyday life. Do our students just understand the general adaptation syndrome of stress31 or do they learn how to manage stress? Can they apply the Yerkes–Dodson law32 to their occupational and sporting life? It is only in this manner that we will be able to identify what is uniquely psychological about psychological literacy.

| Figure 1 Psychology as meta-literacy. |

Current status of research

There is a growing literature conceptualizing psychological literacy but a lack of research to support the conceptualizations. As an example, White33 provides an excellent chapter on how the social psychology of intergroup harmony could be applied in the classroom but without data on actual implementation and outcomes.

We are at the early stages of research in this area, primarily anecdotal, case example, and pilot studies. An important step in clarifying these issues is the article by Wilson-Doenges and Gurung34 establishing benchmarks for scholarship of teaching and learning somewhat equivalent to the standards for empirically validated therapies.35 In the Wilson-Doenges and Gurung34 standards, level 1 is primarily exploratory and pilot research. Level 2 is theory-driven quantitative experimental and in-depth qualitative research. Level 3, the “gold standard”, is theory-driven advanced experimental designs with high internal and external validity using well established measures with good reliability and validity. Very little research on psychological literacy has moved beyond level 1.

Not surprisingly then, the empirical studies that do exist are often plagued by methodological problems that make drawing any kind of definitive conclusions difficult. As an example, a study of senior psychology students mentoring incoming psychology students found that the program benefited both parties.36 Unfortunately, the study relied on self-report, used a single item measure of psychological literacy, and did not have a control group. It also appears that the study suffered from a ceiling effect on its measures, especially with the senior students. Hence, while pre–post self-report seems to have produced a positive effect on psychological literacy, no real conclusions are warranted from this study. Similarly, a potentially very useful study of alumni perceptions37 suffered from a small sample size (N=78) especially in comparison to the number of response items (64) and the sample was from a single university site, with Caucasians and females significantly overrepresented. Lack of comparison groups is a common methodological shortcoming.

A major stumbling block is that there is no agreed-upon measure of psychological literacy. It is clear that simplistic approaches to the conceptualization and measurement of psychological literacy will be inadequate. The number of courses in psychology has been used as a proxy measure.12 Beins et al38 found three main methods of investigating psychological literacy: knowledge of core concepts, reduction in psychological misconceptions, and changes in student perceptions of psychology as a science. The last two provide evidence that an undergraduate psychology degree does increase psychological literacy as operationally defined (primarily knowledge). We have two excellent potential gold standard methods of assessing students’ core knowledge of psychology: the psychology Graduate Record Examinations39 and the Examination for the Professional Practice in Psychology.40 Either we will need to agree upon a common measure of the core knowledge areas of psychology, or each study will need to justify its measurement of the knowledge aspect of literacy. For example, a study may want to look only at the impact of knowledge of developmental psychology on effective parenting.

These aforementioned measures could all address the core knowledge but not the successful application of psychological literacy to personal, interpersonal, occupational, and societal issues. Halpern and Butler30 call for the development of scenario-based measures. Although these would measure the capacity for psychological literacy and might serve as a proxy, there would be no way to know whether psychological literacy is applied in real life. Any clinician knows that role-play in the office does not always translate to the real world. Grasha41 used a “Principle Application Diary Format” to facilitate students’ use of psychological principles in everyday life. This could be a useful platform for the development of qualitative and even quantitative measures of psychological literacy. It may also be the situation that each area of study will require its own measure that will need to be justified on a study-by-study basis.

There is evidence that our current undergraduate education models are failing to achieve an occupational advantage for our students. Many psychology alumni do not see the connections between their undergraduate studies and their current workforce positions42 despite repeated assertions of the widespread applicability of an undergraduate psychology education.43 Employers agree, not just for psychology44 but for the workforce readiness of undergraduates in general.45 A significant issue is that the value of a psychology baccalaureate is often focused on generic undergraduate skills not on psychology-specific skills and knowledge.37 This raises again the question of what unique characteristics do psychology students bring to the workforce. Are psychology alumni better at sales or customer relations or managing by virtue of their psychology training above and beyond generic undergraduate skills? Are we asking employers the right questions? Do we ask what they specifically value from an employee with a psychology background as opposed to the generic skills? So far, it appears not. It might be possible to examine whether professionals with a psychology baccalaureate make better decisions (eg, lawyers, medical doctors, police officers, and teachers, etc). Occupational-specific measures may be necessary in many cases (sales, promotions, performance ratings, etc). Professional quality-of-life measures are another potential outcome measure (eg, ProQOL measure46).

Another focus of the definition is on personal benefits. Quality-of-life measures offer an option for measuring the impact of psychological literacy, especially those with cross-cultural sensitivity (eg, The World Health Organization Quality of Life).47 Other alternatives are life satisfaction scales (eg, Satisfaction with Life Scale)48 or well-being.49 If psychological literacy does give an advantage, then we should see improved quality-of-life scores and lower scores on anxiety, depression, and other measures of psychological functioning (equating for baseline levels since it is well known that students with psychological issues are attracted to the psychology major). However, there does not seem to be any research on psychology alumni’s quality of life.

Miller2 noted “Assessing social innovations is a whole art in itself, one that we are only beginning to develop.” That still seems true 47 years later. How do we evaluate the subtle impact of everyday practical psychology? The impact of psychological literacy on societal issues will be much harder to measure. Perhaps very large-scale studies could look at whether communities with a higher percentage of psychology baccalaureate residents have greater community satisfaction or tolerance or other measure of community well-being. Diener’s50 work on culture and well-being provides a guide in this area.

Best practices: curriculum design and research

The typical psychology undergraduate curriculum is focused on preparation for graduate school,37,44,51 yet the majority of psychology undergraduates do not go on to graduate degrees.52–54 The goals of the psychological literacy movement will push undergraduate psychology away from graduate school preparation toward knowledge and skills that can be applied in everyday life. Psychological literacy may be an essential requirement of future employees21 as well as personal and global wellness.20,55 This may involve turning the curriculum upside down and teaching students what they want to know, not what we think they should know.2,56 Perhaps the place to begin is to answer the questions that nurses, policemen, prison guards, teachers, and salesmen already have.2,41 We need to return to Boneau’s27 idea of identifying what is the core knowledge of psychology, the essentials that every baccalaureate of psychology should know, but refined to include practical, applicable knowledge. Bachelor of Applied Psychology programs57–60 are some early examples of redesigning curriculums around psychological literacy, but as yet, there do not seem to be any published studies comparing their outcomes to traditional theory-oriented curriculums.

Making psychological literacy a primary goal of psychology undergraduate programs raises a very important question. Are professors modeling and using their own psychological literacy? Our research continues to rely too much on convenience samples that are not representative.61,62 In Canada, the most common way teaching skills are acquired by academic psychologists is teaching assistantships.63 Being “thrown in the deep end” hardly seems to be the application of psychological literacy. One could easily argue that the impact of a university professor is equally as important and potentially harmful as that of the clinician. Certainly, the multiplier effect of a successful intervention (teaching) is potentially far greater for the professor than for the clinician seeing clients one at a time.

There has been a call for a “scientist-educator” model of teaching mirroring the scientist-practitioner model for professional psychology.64–66 A search of the PsycINFO database obtained 2,375 hits for the term “scientist practitioner”, whereas “scientist educator” obtained 11. While there are attempts to identify evidenced-based learning (EBL) and evidence-based teaching (EBT),67 these efforts seem to lag far behind the empirically validated treatment movement.

The lack of quality research in regard to psychological literacy means that at the moment, best practices in the classroom are largely based on opinion and very preliminary research. The best reviews to date are “Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline”3 and “The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives”.4 Psychological literacy should be facilitated by EBL and EBT. The Australian Journal of Psychology provides a “snapshot of EBL and teaching”,67 and there is the excellent e-book “Applying Science of Learning in Education: Infusing Psychological Science into the Curriculum” provided by Division 2 of the American Psychological Association.68

We also need to reexamine some previous studies in light of the new concept of psychological literacy. Grasha41 explicitly designed a course in psychological literacy though he called it “practical psychology”. He provided anecdotal and rudimentary quantitative data supporting the personal impact of the course on students including such objective evidence as work commendations and increased sales. However, there were only 33 participants from a single university night class with no control group. Increased political knowledge and engagement in the political process was found for a group of 22 students taking a political psychology course.69 In an abnormal psychology course, students generated and answered questions that friends or family might ask. Students reported increased comfort and readiness in responding to such questions.70 However, there was no way to assess if this generalized outside the classroom. Again, small sample size (N=23) from a single section of a course and no comparison group limit conclusions. What these studies do demonstrate is that courses can be adapted in a mindful manner to achieve rough estimates of what we now call psychological literacy.

Boyer71 proposed that universities were responsible to produce students who “…live lives of dignity and purpose…” and to “… shape a citizenry that can promote the public good.” Barnett72 calls such learning “life-wide education”. This is consistent with the concept of the psychologically literate citizen which in turn is part of becoming a global citizen.51 This means that the undergraduate curriculum will be a starting point for our students to be lifelong learners and we need to give them the skills to do so.36 We need to ensure that by the time psychology majors graduate, they know how to find and evaluate information not just ascertain facts.73 But I would also argue that this should be a generic goal of university education and not exclusive to psychology and hence not specifically psychological literacy. As argued elsewhere in this article, we need to separate psychological literacy from generic student-learning outcomes.

If psychological literacy is to be the primary focus of an undergraduate education, we will need to reevaluate what are considered core courses in psychology and how they are delivered. It has been suggested that students not going on to graduate school do not require statistics and research methods.56 Yet, others would argue that those are still the most essential core courses where psychology undergraduates start to think like psychologists, not just use psychological knowledge.1,74 Should “human interest” courses outweigh methodological courses? Do these methodology courses provide a uniquely psychological edge to our graduates? These are empirical questions. Nursing and social work are applied undergraduate programs that by and large do not teach statistics and methodology. Do psychology undergraduates who do take statistics and methodology courses have an advantage?

Ethical considerations

One notable weakness in the literature is a thorough examination of the ethical issues that will underlie this proposed shift in the curriculum. Baccalaureate psychology graduates face ethical dilemmas. A former student of mine who works with an addiction agency was asked by coworkers to diagnose some of the clients since he had a background in psychology. He declined (an issue we had covered in class) but how he can use the knowledge and skills he acquired as an undergraduate in his work, is a regular question with which he has to struggle. However, the evidence is that undergraduate psychology programs do not adequately train students in ethical thinking.75 It is recognized that the teaching of ethics will need to play a more prominent curriculum role.75–77 But there are other significant issues that have not been addressed.

First, there is the issue of competence. If the curriculum shifts from factual and theoretical learning toward personal growth and development then the lines between teaching and therapy can become blurred. For example, will a course in child development become a course in parent training? The majority of psychology professors are not trained as clinical and counseling psychologists. If a client is concerned with the care received from a professional psychologist, he/she can lodge a complaint with the psychologist’s governing body. That governing body in turn has the authority to investigate and, should an ethical/competence issue be proven, impose sanctions right up to removal from the profession. Will students have similar avenues of recourse? What regulatory body is available with the authority to investigate and impose sanctions on academic psychologists? Could a professor lose tenure and be released from their position?

In a similar vein, we also need to ensure that our baccalaureate students do not think they are now professional psychologists. A marketing professor once introduced herself as a “quasi-psychologist” who was (to paraphrase) “responsible for all that evil that makes you buy stuff”. Is this something we would encourage – for our baccalaureate alumni to see themselves as “quasi-psychologists”? One estimate is that 94% of our students know at least one person with a mental illness.78 Will they now feel entitled to practice psychological literacy on their family and friends? Cranney et al1 list “application to self and close others” as a goal of the undergraduate curriculum. If we are in fact encouraging students to apply their psychological literacy in their everyday lives and communities, does the university then become liable for any misapplication of psychological knowledge by their students and alumni? One part of professional training is being aware of one’s limitations and only providing professional services within the scope of one’s competencies. This will have to become an integrated part of an undergraduate curriculum. This is true for faculty as well as students.

The second issue is boundaries. Prohibitions against dual relationships preclude someone being in a therapeutic role with a student at the same time that they are in a teaching role. How will these distinctions be maintained? Do we take on responsibility for the emotional maturity and personality development of our students as recommended by Landrum et al?37 Will we start marking students on their personal development or wellness?

The third issue is confidentiality. How will this be handled within the context of an open classroom? Self-disclosure will likely increase. Will students be required to sign confidentiality agreements in the classroom? This is becoming increasingly important in an age of such potentially rapid widespread communication.

The fourth issue is informed consent and the right to withdraw. Will students be fully informed of the applied nature of the curriculum and will they sign a consent form agreeing to projects involving personal change? If application to self and close others is a requirement of the undergraduate degree, then can a student be failed for refusal to self-disclose or refusal to engage in a planned exercise for personal change? Will informed consent be obtained from the “close other”?

The fifth issue is accountability. If we are strictly educators, then we are only responsible for providing the knowledge of the field to students. The students are then free and responsible for how they use that information. If we require ethical application of psychological literacy, then we are taking on a whole new level of responsibility with potentially large pedagogical and legal implications. If we teach with the intent that our students implement their literacy, then can we be held accountable for the misapplication of that knowledge in the same way a clinical supervisor can be held accountable for the missteps of their protégés? We may fall into de facto undergraduate professional training.

The sixth issue is respect for the individual, including autonomy. There is a fine line between education and indoctrination. There is a clear value matrix underlying the psychological literacy movement and while it is one with which I am in agreement, care must be taken that we are not closed to dissenting points of view. Attention has recently been drawn to the increasing homogenization of the political spectrum in psychology and the potential negative implications of this lack of diversity.79 White33 says it is not enough to impart knowledge and skills but students must have “…the courage of their convictions to actually practice these principles at every opportunity that requires it” echoing McGovern et al’s29 statement: “Cognitive and affective insight must go hand-in-hand with behavioral changes.” This moves dangerously close to indoctrination if our students have to use their psychological literacy in ways approved by “us”. It causes me to remember with a chill the “D” I received on a first-year history paper for the sole reason that I did not adopt the professor’s far left political perspective.

We might hope that our students will use their psychological knowledge for societal benefit, but what if they do not? Who will decide if it is beneficial or not? Psychology has a dark side. It has been called: “…an important weapons system” by the US Army Surgeon General.80 Psychologists have developed and participated in “enhanced interrogations”.81 It has been used to “convert” homosexuals.82 Marketing experts use psychology every day to influence our perceptions, wants, and needs,83 not always for the betterment of society. Psychology can cause harm.84–86 Will it behoove us to screen our students not only for academic qualifications but for character and moral attributes as well? Alternately, one could argue that the very potential and dangerousness of psychology is why it should be as widely dispersed as possible; that it is too powerful to be entrusted to an elite no matter how beneficent they see themselves.

Psychologists do not even agree on whether there is a discipline obligation to promote social justice. Indeed, the American Psychological Association deleted the principle of social responsibility in the 2002 revision of its code of ethics.87 We also need to remember that society has not mandated psychology to change it.2

Further cautions

Sternberg76 offered a number of cautions that seem to have been ignored. An excessive focus on pragmatics might be at the expense of theory and “big ideas”. Over analysis of one’s personal and occupational life, and over application of psychological concepts are also dangers of an overly zealous push for psychologically literate student citizens. Miller2 warns that piecemeal application of psychological principles often fails. Psychological knowledge has to be integrated into the context of the whole.

The factual side of psychological literacy is a moving target,76 and our core psychological knowledge is more culturally bound than previously believed.61 In an article that should be mandatory reading in research method classes around the world, Henrich et al demonstrate in compelling fashion how often findings from Western samples fail to generalize to other populations in a wide range of areas:

The domains reviewed include visual perception, fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, categorization and inferential induction, moral reasoning, reasoning styles, self-concepts and related motivations, and the heritability of IQ.61

In some ways, the movement toward psychological literacy is simply a return to the goal of creating Rogers’ “persons of tomorrow”.20 Yet, this conceptualization of psychological literacy may be overly imbued with Western values.55,61 At the Sixth International Conference on Psychology Education, one African delegate spoke eloquently of how he did not see himself reflected in the predominately Western psychological literature.88 We also must be very cautious that the psychological literacy that we teach is not the imposition of a uniquely Western perspective from a position of power and privilege.

Conclusion

Increased psychological literacy is a laudable goal. Indeed, how could one argue against the effective application of psychological knowledge toward the enhancement of people’s personal, occupational, and social lives? The potential benefits of a psychological literate society are immense but so are the dangers. Progress toward this goal is desirable, but there needs to be a healthy dose of caution and greater consideration of the potential negative outcomes as well as the positive. The impact on society of hundreds of thousands of baccalaureate psychology students actively utilizing their knowledge is as yet unrealized or at least unmeasured, particularly in terms of the intentional teaching of psychological literacy.

We need to decide whether psychological knowledge is so powerful and dangerous that only an elite of highly (graduate school) trained practitioners should be allowed to apply these principles (the current model) or whether it is so ubiquitously, positively useful that we want as many citizens as possible to be active in the application of their psychological literacy (the proposed model). This is a debate that has underscored psychology at least since Adler split with Freud. Or, is there a middle ground? Can we thoughtfully and empirically decide what parts of psychology can be “given away” and what parts need to be retained for only those with significant training? Do I really need a doctoral degree to teach assertiveness skills or progressive relaxation? However, I would be concerned with anyone who had less than a Masters degree in psychology integrating and interpreting psychological assessment material.

Psychological literacy could and should be a goal of a psychology undergraduate education, but it does not need to be the goal. We cannot lose sight of the top students who will go on to graduate studies in psychology. They will still need intensive courses that provide them with the factual and theoretical knowledge as well as the skills necessary to succeed at graduate school. We need to be able to accommodate the student who has an intellectual, not a pragmatic interest in psychology. We need to accommodate those students who do not wish to enter into a relationship with their instructor that requires “application to self and close others”. More does need to be accomplished, however, for the majority of students who do not go on to graduate school and need clearly identified, marketable skills. While some would argue that job preparation is not the function of universities,71 most of our baccalaureates will be seeking employment.

The solution would seem to be to have some but not all undergraduate courses have a psychological literacy (in the sense of application) component. Capstone courses,89 service learning courses,90,91 and community-based practicums seem logical candidates for incorporating psychological literacy. The option to not take such a course or to have an alternate assignment must be present, however, to not violate the concept of informed consent. We will also need to ensure that the instructors in those courses have the necessary competence. All the ethical issues noted earlier will have to be considered and addressed.

I have also contended in this review that psychological literacy is meta-literacy: a higher order literacy that requires and incorporates other essential literacies. It requires and utilizes other literacies that are expected of all undergraduate students regardless of discipline but is the knowledge and skills that only psychology students possess. Therefore, as a discipline and a profession, we need to answer the question: what makes psychology unique?12 This problem is not restricted to undergraduate education. There is a need to establish what distinguishes professional psychologists from other service providers12 and is therefore marketable.92 We have argued previously that one of the distinguishing characteristics of professional psychologists is the very breadth and depth of our knowledge and the ability to integrate multiple theoretical perspectives.12 The bane of our existence as a profession is that we have no exclusive scope of practice. Everything psychologists can do, at least one other profession can do. However, this is also the very strength of our field. Psychology could already be considered an interdisciplinary field of study incorporating biology, physiology, neurosciences, sociology, anthropology, philosophy, ethics, and linguistics, as well as other fields of study. Our ability to integrate biological–psychological–social models of understanding of human behavior is the foundation stone of what make us unique. We are no longer just the middle part of that integrated paradigm.

Recommendations

- A working operational definition of psychological literacy will require an articulation of what is uniquely psychological in student-learning outcomes for our undergraduates.

- We need standardized outcome measures that allow us to measure the impact of this operational definition. This will likely involve multiple measures to capture all aspects of the impact of psychological literacy.

- We need good quality studies comparing psychology alumni to other disciplines involving appropriate comparison populations. We need to avoid confounding intelligence with university attendance, for example, and equating or controlling for prior adverse experiences and difficulties with mental health issues since many students with such issues are attracted to psychology in the first place.78

- At least some of these studies of alumni will need to be longitudinal to see if psychology literacy has a lasting impact, positive or negative.

- We need a reevaluation of what are considered core courses in psychology and how they are delivered. Do all courses have to have a psychological literacy component or just some?

- Curriculum decisions will need to include whether psychology needs two streams: a terminal applied stream and a graduate school-oriented theoretical/methodological stream. Alternately, the Australian model of a 3-year general degree (modified to a more pragmatic degree) and a fourth year, graduate school preparatory year, has merits that are worth exploring.

- Service-learning initiatives91 and volunteerism are a good fit with psychological literacy.93,94 The potential of these educational opportunities needs to be properly evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank James Taylor, Evelyn Field, Verna Raab, Ann Kus, and Dominick Murdoch for their review and insightful comments of earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Cranney J, Botwood L, Morris S. National Standards for Psychological Literacy and Global Citizenship : Outcomes of Undergraduate Psychology. Office for Learning & Teaching, Government of Australia. Sydney, NSW: 2012. | ||

Miller GA. Psychology as a means of promoting human welfare. Am Psychol. 1969;24(12):1063–1075. | ||

Halpern DF. In: Halpern DF, editor. Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. | ||

Cranney J, Dunn DS. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. | ||

American Psychological Association [webpage on the Internet]. Science of Psychology; 2016:1. Available from: http://www.apa.org/action/science/. Accessed February 7, 2016. | ||

Slavich GM. On 50 years of giving psychology away: an interview with Philip Zimbardo. Teach Psychol. 2009;36(4):278–284. | ||

Zimbardo PG. Does psychology make a significant difference in our lives? Am Psychol. 2004;59(5):339–351. | ||

Psychology Works Fact Sheets [webpage on the Internet]. Psychol Fact Sheets; 2016:1. Available from: http://www.cpa.ca/psychologyfactsheets/. Accessed February 6, 2016. | ||

Klavans R, Boyack KW. Toward a consensus map of science. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2009;60(3):455–476. | ||

Boyack KW, Klavans R, Börner K. Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics. 2005;64(3):351–374. | ||

Borins M, Holzapfel S, Tudiver F, Bader E. Counseling and psychotherapy skills training for family physicians. Fam Syst Health. 2007;25(4):382–391. | ||

Murdoch DD, Gregory A, Eggleton JM. Why psychology? An investigation of the training in psychological literacy in nursing, medicine, social work, counselling psychology, and clinical psychology. Can Psychol. 2015;56(1):136–146. | ||

Talbot F, Clark DA, Yuzda WS, Charron A, McDonald T. “Gatekeepers” perspective on treatment access for anxiety and depression: a survey of new Brunswick family physicians. Can Psychol. 2014;55(2):75–79. | ||

Wynaden D, Orb A, McGowan S, Downie J. Are universities preparing nurses to meet the challenges posed by the Australian mental health care system? Aust N Z J Ment Health Nurs. 2000;9(3):138–146. | ||

Bland R, Renouf N. Social work and the mental health team. Australas Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):238–242. | ||

Mostofsky DI. Social science, behavioural medicine, and the tomato effect. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(2):313–316. | ||

Cronin M [webpage on the Internet]. Scientific Literacy? Politicians Make Embarrassing Gaffes About Science, Technology. Huffington Post; 2012. Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/03/scientific-literacy-politicians-gaffes_n_1825314.html. Accessed November 21, 2015. | ||

Oppong S. Psychology, economic policy design, and implementation: contributing to the understanding of economic policy failures in Africa. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2014;2(1):183–196. | ||

Lickerman A [webpage on the Internet]. Why Politicians Should Have Backgrounds in Clinical Psychology. KevinMD; 2013:1. Available from: http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2013/05/politicians-backgrounds-clinical-psychology.html. Accessed February 6, 2016. | ||

O’Hara M. Psychological literacy for an emerging global society: another look at Rogers’ “persons of tomorrow” as a model. Pers Exp Psychother. 2007;6(1):45–60. | ||

Roberts LD, Heritage B, Gasson N. The measurement of psychological literacy: a first approximation. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1–12. | ||

Lilienfeld SO, Lynn SJ, Ruscio J, Beyerstein BL. 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions About Human Behavior. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. | ||

James C. Law student wellbeing: benefits of promoting psychological literacy and self-awareness using mindfulness, strengths theory and emotional intelligence. Leg Educ Rev. 2011;21(2001):217–233. | ||

Scherger EJ. Foreword. In: Frank RG, McDaniel SH, Bray JH, Heldring M, editors. Primary Care Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:xi–xii. | ||

van den Heuvel M, Barozzino T, Milligan K, Ford-Jones E, Freeman S. We need psychologists! Pediatr Child Health. 2016;21(1):e1–e3. | ||

Hong B [webpage on the Internet]. The teaching of psychology and the new MCAT. Psychol Teach Netw. 2012;22(2). Available from: http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/ptn/2012/08/mcat.aspx. Accessed November 22, 2015. | ||

Boneau CA. Psychological literacy: a first approximation. Am Psychol. 1990;45(7):891–900. | ||

Burnett N, Packer S, Nicole B, et al. Education for All: Literacy for Life. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; UNESCO, 2005. Available from: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/efareport/reports/2006-literacy/. Accessed March 3, 2016. | ||

McGovern TV, Corey L, Cranney J, et al. Psychologically literate citizens. In: Halpern DF, editor. Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010:9–27. | ||

Halpern DF, Butler H. Critical thinking and the education of psychologically literate citizens. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:27–40. | ||

Selye H. Stress without Distress. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1974. | ||

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol. 1908;18(5):459–482. | ||

White FA. The social psychology of intergroup harmony and the education of psychologically literate citizens. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:56–71. | ||

Wilson-Doenges G, Gurung RAR. Benchmarks for scholarly investigations of teaching and learning. Aust J Psychol. 2013;65(1):63–70. | ||

Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685–716. | ||

Burton LJ, Chester A, Xenos S, Elgar K. Peer mentoring to develop psychological literacy in first-year and graduating students. Psychol Learn Teach. 2013;12(2):136–146. | ||

Landrum RE, Hettich PI, Wilner A. Alumni perceptions of workforce readiness. Teach Psychol. 2010;37(2):97–106. | ||

Beins B, Landrum E, Posey D. Specialized Critical Thinking: Scientific and Psychological Literacies. Society for the Teaching of Psychology, Washington, DC: 2011. | ||

Kuncel NR, Hezlett SA, Ones DS. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the predictive validity of the graduate record examinations: implications for graduate student selection and performance. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):162–181. | ||

DeMers ST. Understanding the purpose, strengths, and limitations of the EPPP: a response to Sharpless and Barber. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40(4):348–353. | ||

Grasha AF. “Giving Psychology Away”: some experiences teaching undergraduates practical psychology. Teach Psychol. 1998;25(2):85–88. | ||

Borden VMH, Rajecki DW. First-year employment outcomes of Psychology Baccalaureates: relatedness, preparedness, and prospects. Teach Psychol. 2000;27(3):164–168. | ||

Landrum RE. I’m getting my bachelor’s degree in psychology – what can I do with it? Psi Chi J. 2001;6(1):1–5. | ||

Landrum RE, Harrold R. What employers want from psychology graduates. Teach Psychol. 2003;30(2):131–133. | ||

Hart Research Associates. Falling Short ? College Learning and Career Success. Washington, DC; 2015. Available from: https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2015employerstudentsurvey.pdf. | ||

Stamm BH [webpage on the Internet]. ProQOL Measure. ProQOL.org; 2016. Available from: http://www.proqol.org/ProQol_Test.html. Accessed February 22, 2016. | ||

World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL); 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/whoqol/en/. Accessed February 21, 2016. | ||

Diener E [webpage on the Internet]. Satisfaction with Life Scale; 2009. Available from: http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/∼ediener/SWLS.html. Accessed February 22, 2016. | ||

Forgeard MJC, Jayawickreme E, Kern ML, Seligman MEP. Doing the right thing: measuring well-being for public policy. Int J Wellbeing. 2011;1(1):79–106. | ||

Diener E. In: Diener E, editor. Culture and Well Being: the Collected Works of Ed Diener. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. | ||

Cranney J, Dunn DS. Psychological literacy and the psychologically literate citizen: new frontiers for a global discipline. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2011:3–12. | ||

American Psychological Association Center for Workforce Studies [webpage on the Internet]. Frequently Asked Questions; 2016. Available from: http://www.apa.org/workforce/about/faq.aspx#II.2. Accessed January 22, 2016. | ||

Trapp A, Banister P, Ellis J, Latto R, Miell D, Upton D. The Future of Undergraduate Psychology in the United Kingdom. Higher Education Academy Psychology Network, University of York, York: 2011. | ||

Cranney J, Turnbull C, Provost SC, et al. Graduate attributes of the 4-year Australian undergraduate psychology program. Aust Psychol. 2009;44(4):253–262. | ||

Marsella AJ. Toward a “global-community psychology”: meeting the needs of a changing world. Am Psychol. 1998;53(12):1282–1291. | ||

Rajecki DW, Appleby D, Williams CC, Johnson K, Poynter Jeschke M. Statistics can wait: career plans activity and course preferences of American psychology undergraduates. Psychol Learn Teach. 2004;4(2):83. | ||

Douglas College [webpage on the Internet]. Bachelor of Arts in Applied Psychology; 2016. Available from: http://www.douglascollege.ca/programs-courses/faculties/humanities-social-sciences/psychology/bachelor-of-arts-in-applied-psychology. Accessed June 29, 2016. | ||

St. Lawrence College. Bachelor of Applied Arts Degree in Behavioural Psychology. Available from: https://admissions.carleton.ca/transfer-credits/st-lawrence-college-bachelor-of-applied-arts-behavioural-psychology-4-years/. Accessed January 19, 2016. | ||

Kwantlen Polytechnic University [webpage on the Internet]. Psychology: Bachelor of Applied Arts (Also: Honours); 2013. Available from: http://www.kpu.ca/calendar/2014-15/arts/psychology-applied-deg.html. Accessed January 19, 2016. | ||

Concordia University College of Alberta [webpage on the Internet]. Four-Year BA in Psychology (Applied Emphasis); 2016. Available from: http://psychology.concordia.ab.ca/program-details/. Accessed January 19, 2016. | ||

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33(2–3):61–83; discussion 83–135. | ||

Arnett JJ. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am Psychol. 2008;63(7):602–614. | ||

Skinner NF, Browering ME. Teaching psychology and teaching academic psychologists: a Canadian perspective. In: McCarthy S, Karandashev V, Stevens M, et al., editors. Teaching Psychology Around the World. 2nd ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2009:413–423. | ||

Bernstein DJ, Addison W, Altman C, et al. Toward a scientist-educator model of teaching psychology. In: Halpern DF, editor. Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010:29–45. | ||

Bernstein D. A scientist-practitioner perspective on psychological literacy. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011:281–295. | ||

Groccia JE, Buskist W. Need for evidence-based teaching. New Dir Teach Learn. 2011;128:5–11. | ||

Dunn DS, Saville BK, Baker SC, Marek P. Evidence-based teaching: tools and techniques that promote learning in the psychology classroom. Aust J Psychol. 2013;65(1):5–13. | ||

Benassi VA, Overson CE, Hakala CM, editors. Applying Science of Learning in Education: Infusing Psychological Science into the Curriculum. Washington DC: Division 2, American Psychological Association; 2014. | ||

Isbell LM. Teaching an undergraduate course in political psychology. Teach Psychol. 2003;30(2):148–153. | ||

Pury CL. What are students telling their friends? Teaching responses to lay psychopathology questions. Teach Psychol. 2003;30(2):145–146. | ||

Boyer EL. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass; 1990. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/tl.51. Accessed February 6, 2016. | ||

Barnett R. Life-wide education: A new and transformative concept for higher education? In: Proceedings of Enabling a More Complete Education; 2010:1–12. Available from: http://lifewidelearningconference.pbworks.com/E-proceedings. Accessed February 6, 2016. | ||

American Psychological Association [webpage on the Internet]. APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major: Version 2.0; 2013. Available from: http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/about/psymajor-guidelines.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2016. | ||

Stricker G, Trierweiler SJ. The local clinical scientist. A bridge between science and practice. Am Psychol. 1995;50(12):995–1002. | ||

Davidson GR, Morrissey SA. Enhancing ethical literacy of psychologically literate citizen. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:41–55. | ||

Sternberg RJ. The promise and perils of thinking like a psychologist. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:vi–x. | ||

Dunn DS, Cautin RL, Gurung RAR. Curriculum matters: structure, content and psychological literacy. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford Univ Press; 2011:15–26. | ||

Connor-Greene PA. Family, friends, and self: the real-life context of an abnormal psychology class. Teach Psychol. 2000;28(3):210–212. | ||

Duarte JL, Crawford JT, Stern C, Haidt J, Jussim L, Tetlock PE. Political diversity will improve social psychological science. Behav Brain Sci. 2015;38:e130. | ||

Levine A [webpage on the Internet]. Collective Unconscionable: How Psychologists, the Most Liberal of Professionals Abetted Bush’s Torture Policy. Wash Mon; 2007. Available from: http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2007/0701.levine.html. Accessed February 17, 2016. | ||

McCoy AW. Science in Dachau’s shadow: Hebb, Beecher and the Development of CIA psychological torture and modern medical ethics. J Hist Behav Sci. 2007;43(4):401–417. | ||

Tufford L, Newman PA, Brennan DJ, Craig SL, Woodford MR. Conducting research with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual populations: navigating research ethics board reviews. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2012;24(3):221–240. | ||

Joireman J, Liu RL, Kareklas I. Images paired with concrete claims improve skeptical consumers’ responses to advertising promoting a firm’s good deeds. J Mark Commun. 2016;7266(February):1–20. | ||

Jarrett C. When therapy causes harm. Psychologist. 2008;21(1):10–12. | ||

Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2(1):53–70. | ||

Lilienfeld SO. Scientifically unsupported and supported interventions for childhood psychopathology: a summary. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):761–764. | ||

Pettifor JL. Professional ethics across national boundaries. Eur Psychol. 2004;9(4):264–272. | ||

Baloyi L. From Teaching Psychology in Africa to Teaching African Psychology: Challenges, Myths and Insights. 6th Int Congr Psychol Educ (ICOPE 6); 2014. Available from: icope6.interteachpsy.org/aug5/panel/LesibaBaloyi.pptx. Accessed February 8, 2016. | ||

Grayson JH. Capping the undergraduate experience: making learning come alive through fieldwork. In: Dunn DS, Beins B, McCarthy MA, Hill GW 4th, editors. Teaching Beginnings and Endings in the Psychology Major. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:279–298. | ||

Moely BE, McFarland M, Miron D, Mercer S, Ilustre V. Changes in college students’ attitudes and intentions for civic involvement as a function of service-learning experiences. Mich J Community Serv Learn. 2002;9(1):18–26. | ||

Bringle RG, Reeb RN, Brown MA, Ruiz AI. Service Learning in Psychology: Enhancing Undergraduate Education for the Public Good. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2016. | ||

Murdoch D. What can we learn from IBM, Sony and Apple? Psynopsis. 2013:19. | ||

Charlton S, Lymburner J. Fostering psychologically literate citizens: a Canadian perspective. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychological Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspective. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:336. | ||

Sokol BW, Kuebli JE. Psychological literacy: Bridging citizenship and character. In: Cranney J, Dunn DS, editors. The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford; 2010:269–280. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.