Back to Journals » Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology » Volume 10

Perianal Crohn's disease: challenges and solutions

Authors Kelley KA, Kaur T, Tsikitis VL

Received 27 September 2016

Accepted for publication 15 January 2017

Published 8 February 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 39—46

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S108513

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Andreas M. Kaiser

Katherine A Kelley, Taranjeet Kaur, Vassiliki L Tsikitis

Department of General Surgery, Division of Gastrointestinal and General Surgery, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, OR, USA

Abstract: Perianal Crohn’s disease affects a significant number of patients with Crohn’s disease and is associated with poor quality of life. The nature of the disease, compounded by presentation of various disease severities, has made the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease difficult. The field continues to evolve with the use of both historical and contemporary solutions to address the challenges associated with it. The goal of this article is to review current literature regarding medical and surgical treatment, as well as the future directions of therapy.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, fistula, surgery, perirectal

Introduction

Perianal disease is commonly diagnosed in individuals with Crohn’s disease (CD). It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses.1,2 The incidence of perianal Crohn’s disease (pCD) ranges from 17% to 43% of CD cases.1,3,4 pCD is associated with more distal CD.3 In 5% of individuals, however, CD will only manifest as perianal disease without associated luminal disease.1,5 Individuals will most commonly develop perianal disease prior to the diagnosis.1

pCD is particularly difficult to manage, due to the complexity of its presentation. The incidence of pCD is similar in men and women. Women, however, have greater complications associated with the adjacent vaginal wall and risks associated with childbirth.6 Patient-reported symptoms associated with it include pain with associated perianal swelling and fevers, drainage of pus, stool, or blood from the vagina, scrotum, or perineum. Some may report fecal incontinence. The disease may physically manifest as a perianal fistula, anal fissure, anal canal stricture, rectovaginal fistula, or abscess.7 The etiology of the pCD is still unclear; theories suggest it arises from deep ulcers or anal gland abscesses. It is most likely a combination of genetic, microbiologic, and immunologic factors.8

Current clinical classifications for pCD were proposed by the American Gastroenterological Association.7 Fistulas are distinguished as simple and complex fistulas. Simple fistulas are low, below the dentate line, and include superficial, intersphincteric, or intrasphincteric fistulas, with a single external opening without other complications. Complex fistulas are high, arising above the dentate line, and may have multiple external openings. They may be associated with perianal abscesses, rectal stricture, proctitis, or connections with the bladder or vagina. This classification has been elaborated to include a clinical activity score using the Perianal Disease Activity Index, described by Irvine.9 This classification includes the evaluation of five elements: fistula discharge, pain and restriction of activities, restriction of sexual activity, type of perianal disease, and degree of induration.9 In addition, the Fistula Drainage Assessment Measure classifies fistulas as being either open and actively draining or closed.9,10

This article will provide a brief summary of diagnostic strategies, current medical and surgical therapies for pCD, and future directions for therapies, focusing on the use of stem cells.

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing of pCD is to obtain a thorough history and physical examination. History should include anorectal pain, purulent discharge, persistent drainage, rectal bleeding, recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), or fecal incontinence. Exam under anesthesia (EUA) remains the standard for diagnosis and classification of perianal fistula with an accuracy of up to 90% when diagnosing pCD.11 It should be performed by a specialized surgeon well-versed in the disease process. During an EUA, abscesses will be drained, fistula tracts will be delineated, and setons placed if indicated. During the examination, close attention is directed to the vaginal wall and scrotum to assess for complex fistulous tracts. EUA with abscess drainage and seton placement is considered the first step prior to antitumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) intervention, and results in higher resolution and lower recurrence.12 In combination with EUA, endoscopy may also facilitate the identification of luminal inflammation and the presence of internal openings, while strictures and cancer are excluded.13

The above diagnostic strategies are aided by the addition of endoanal ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In EUS, a high frequency endoluminal probe that produces 2D and 3D ultrasound images is utilized to visualize all sphincter structures.14 The addition of hydrogen peroxide during EUS also enhances the identification of fistula tracts.15,16 The most recent meta-analysis reported a sensitivity of 0.87 and specificity of 0.43 for EUS.17 Pelvic MRI is now considered the noninvasive gold standard for perianal fistula assessment, and the most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 0.87 and specificity of 0.59.17 T2-weighted sequence with fat suppression is the optimal technique for MR fistula imaging, while a gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted sequence is useful for the differentiation of fluid, pus, or granulation tissue.18 MRI is also capable of identifying clinically silent abscesses and inflammation.19 Schwartz et al compared pelvic MRI and EUS with a reported accuracy of 91% and 87%, respectively, compared to an EUA at 91%.11 Currently, the higher diagnostic quality of EUS and pelvic MRI precludes the use of computed tomography and fistulography.

Treatment

Medical

Medical therapy is a critical adjunct in the treatment of pCD, and should be started once the diagnosis of active pCD is made. The main goal of therapy is to achieve and maintain disease remission.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used to treat perianal sepsis and act as an effective bridge to immunosuppressive therapy.20 A positive clinical response within 6–8 weeks of initiation of treatment is observed in 70%–95% of patients.21 In mild-to-moderate symptoms, treatment with oral metronidazole has been used as the initial therapy, with improved symptoms in 50% of patients.22 Fistula healing rates from antibiotic therapy alone, however, are <50%, and the majority of cases will recur if antibiotics are withdrawn.23

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression is the definitive therapy for pCD. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) are thiopurines that halt DNA replication, and are used for induction and maintenance of remission in fistulizing disease. A meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials examined the efficacy of 6-MP and azathioprine, and demonstrated a 54% healing rate in patients versus 21% of controls.24 Cyclosporine and tacrolimus have been used, but less frequently. Cyclosporine, a T-cell suppressant, when given intravenously has an excellent, rapid effect in up to 83% of patients,25,26 but is not as effective when administered orally. In a randomized controlled trial, tacrolimus, an interleukin-2 (IL-2) inhibitor, resulted in improvement of CD symptoms in 43% of patients versus 8% in the placebo arm.27 Neither cyclosporine nor tacrolimus, however, were specifically studied in fistulizing pCD.

TNF antagonists

TNF antagonists are effective in achieving durable remission in pCD. First, infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, and was evaluated in the ACCENT 1 and 2 trials. ACCENT 1 demonstrated successful induction therapy with infliximab for fistulizing pCD: 68% of patients treated with infliximab had at least a 50% improvement in symptoms versus 26% with a placebo.28 The ACCENT 2 trial documented longer time to recurrence of fistulas with infliximab maintenance therapy.29 In addition, treatment with infliximab prevented additional surgeries and hospitalizations.30 Interestingly, rectovaginal fistula healing had a poor response to infliximab therapy, compared to perianal fistula healing.29,31

Second, adalimumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against TNF-α. In the CHOICE trial, 673 patients achieved complete fistula healing after 8 weeks of adalimumab therapy.32 In a post hoc analysis of the CHARM trial, complete fistula closure was seen at 1 year in 39% of patients treated with adalimumab, versus 13% in the placebo arm. These results were shown to be durable at 2 years.33 A retrospective cohort study comparing infliximab and adalimumab in achieving and maintaining closure of perianal fistulas in ambulatory CD patients demonstrated complete response in 77.0% of patients at 36 months of follow-up, with no difference between infliximab and adalimumab.10

Third, certolizumab pegol has improved solubility and decreased immunogenicity compared with the other TNF antagonists.34 Durable remission for at least 4 years and healing of perianal fistula in 36% of patients was reported.35 All three major TNF antagonist antibodies are effective in pCD, but head-to-head comparisons have not yet been performed.

In summary, the medical approach to the treatment of pCD is evolving. Recently, Choi et al identified a significantly greater proportion of healing in septic perianal disease with the addition of anti-TNF interventions in a retrospective review of 114 patients. Their treatment algorithm appears to be quite successful.36 In the past, therapy has been increased in a stepwise fashion to achieve remission, adding increasingly potent immunosuppressant medications. The value of early combination therapy to prevent disease progression may find a role in fistulizing pCD (REACT trial),37 or the addition of anti-TNF agents earlier in therapy.

Surgical

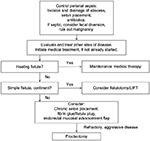

Surgical interventions for pCD vary, depending on disease extent and severity and can be facilitated by concurrent use of medical therapy (Figure 1). Although an attempt is made to be conservative with surgical interventions, the overarching goal is to manage perianal sepsis, drain any abscesses, and place setons in delineated fistulas. Treatments can be highly variable among practitioners, requiring a multidisciplinary approach.38 Here, we have reviewed specific Crohn’s literature regarding surgical interventions (Table 1). Perianal abscesses, which commonly precede or accompany perianal fistulas, should be incised and drained when first identified.39 Surgical drainage, as opposed to spontaneous drainage, minimizes the risk of further septic complications.40 It is important to note that the surgical removal of skin tags associated with pCD is not recommended, due to the risk of poor wound healing, infection, and fistula formation.41 If fistulas are identified at the time of intervention, noncutting seton placement is recommended, which will maintain patency of the fistula tracts and limit recurrent abscess formation.42 Seton placement allows drainage without closure and increases effectiveness of medical therapy, while preserving external sphincter function.42,43 Fistulotomies at the time of perianal sepsis are contraindicated, as there is an increased risk of incontinence.44 The rate of incontinence after seton placement is 12%.45 One should also consider the addition of an anti-TNF antibody, which has been shown to improve response rate, recurrence rate, and time to recurrence.12 The duration of seton placement is not clear; studies, however, have reported that effective treatment is observed after longer durations of infliximab, and setons may be removed.40,46 Our institution waits at least 6 weeks before any further surgical intervention is discussed.

| Figure 1 Suggested algorithm for treatment and management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Abbreviation: LIFT, intersphincteric fistula tract. |

| Table 1 Summary of the literature on perianal Crohn’s disease interventions Abbreviation: LIFT, intersphincteric fistula tract. |

After resolution of perianal sepsis and remission of active distal disease, a fistulotomy is the preferred procedure, for simple, superficial fistulas. The tract is identified, the overlying tissue is divided, the base of the tract is curetted, and the wound is left open to close by secondary intention. In addition, marsupilization may improve the rate of wound healing.47 Successful healing is reported in ~80% of patients with a 20% risk of recurrence over a follow-up between 2 and 20 years.42,48–50 Fistulotomy is strongly discouraged in complex fistulas, due to high risk of fecal incontinence, decreased healing, and need for proctectomy.50,51 Minor continence issues following fistulotomy occur in 25% of patients.52

Other interventions include the use of fibrin glue, which consists of two parallel syringes of fibrinogen and thrombin that facilitate healing, hemostasis, and angiogenesis. These syringes are injected together via a catheter to fill a fistula tract, resulting in clot formation, sealing the fistula. Current literature is discordant with the success of this intervention.53,54 One dedicated randomized controlled trial55 found 38% of patients experienced remission with fibrin glue, which was twice than that for individuals with no intervention; this, however, was in 16 weeks of follow-up. These results echo smaller series previously performed that demonstrated healing in 31% of patients with pCD after fibrin glue over 26 months.54

The Surgisis (COOK biotech, West Lafayette, IN, USA) fistula plug is a lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa. It is inert, eliciting no foreign body or inflammatory reaction, and acts as a collagen scaffold, that is populated by a patient’s endogenous cells over the course of 3 months.56 A recent systematic review of the fistula plug in normal patients demonstrated a closure rate of 58.4% after a median follow-up of 9 months. Most recently, a prospective randomized trial of 106 patients randomized to plug versus seton removal only; fistula closure was 31.5% versus 23.1%, respectively, over 12 weeks of follow-up.57

The ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) is designed to close complex fistulas with sphincter preservation. An incision is made in the intersphincteric groove at both the internal and external sphincters. The external tract is then curetted out, and the external opening is widened at the skin. Eventually, the skin is closed.58 LIFT is a safe procedure that provides a mean healing rate of 70.6% with no reports of impairment of the sphincter function, based on a systemic review with follow-up between 4 weeks and 26 months (average 10.3 months).59 In prospective studies, healing was seen in 67% of patients at 12-month follow-up.60 A prospective observational study concluded the LIFT procedure has a high success rate (94.1% in 167 patients) in complex fistulae-in-ano. Recurrence is associated with diabetes, perianal abscesses, tract abscesses, and multiple tracts. A second LIFT procedure may be a feasible intervention if needed.61

The endorectal mucosal advancement flap is a procedure that uses endogenous tissue to close the internal fistula opening. After complete excision of the fistula tract, the internal sphincter muscle is mobilized and approximated in the middle without tension. A flap is created consisting of mucosa, submucosa, and circular muscle, which is advanced and secured to cover the internal opening.62 Endorectal mucosal advancement flaps are the preferred approach for complicated anorectal fistulae without incontinence. Prior to advancement flap, most patients undergo a period of infection control with a draining seton, with or without a diverting stoma. Relative contraindications to advancement flap are anal stenosis and active proctitis due to high complication and failure rates. van Koperen et al63 reported that 52% of the population undergoing treatment with the mucosal advancement flap experienced healing after 11 months. A retrospective review of 127 patients with high anorectal fistulas had an overall recurrence rate of 26% with a mean follow-up of 13 months.63 Mucosal advancement flaps with or without the addition of fibrin glue have been shown to result in healing rates as high as 62% in complex fistulas.64

Fistulas that do not respond to aggressive medical and surgical management may require fecal diversion with the creation of an ileostomy.65,66 Diversion may result in relief of local inflammation.67 In patients who underwent fecal diversion and drainage of local sepsis for their perianal disease, 81% went into early remission, although 68% of these relapsed at a median of 23 months after treatment. In this same group, a total of 25% of patients had long-term remission, but only 10% were able to restore intestinal continuity,68 which had been reported by others.19,69

Patients with complex fistulas associated with abscesses, recurrent sepsis, colonic or perineal disease, refractory proctitis, and anal stenosis are candidates for proctectomy and permanent stoma.19 Some authors recommend doing this in a two stage procedure to allow resolution of perianal sepsis.44 Furthermore, after resolution of sepsis, there may be large subcutaneous tissue defects, which may require advanced tissue transfers, such as gluteal flaps and gracilis flaps.70 Ileal pouch anal anastomosis has been attempted in these individuals; high rates of recurrence of pCD, however, have been reported. Therefore, we at our institution do not strongly recommend this procedure.71 Colo-anal pull-through is another surgical option; fistula recurrence, however, has been reported up to 25%, although the study did not define which of those occurred in Crohn’s patients. Thirteen percent developed anal strictures, and only 38% returned to normal continence.72 We do not perform this procedure at our institution.

Other interventions

Other interventions have been used to manage pCD. Local injections of anti-TNF alpha have been attempted. Two pilot studies were completed that demonstrated some improvement with injection of infliximab and adalimumab.73,74 Hyperbaric oxygen may also be utilized to facilitate healing.75 In addition, topical tacrolimus has been attempted, but with little success.76,77 Although multiple avenues in treatment have been attempted, it appears surgical intervention remains the most successful.

Future directions

Promising evidence suggests that the injection of stem cells may improve healing in fistulizing pCD. They are nonhematopoietic precursors of connective tissue cells with anti-inflammatory and tissue regenerative properties, extracted from subdermal adipose tissue.78 Peri- or intrafistula injection of autologous adipose-derived stem cells, as well as bone marrow-derived stem cells, is proven to be feasible and safe.79,80 Most recent trials have demonstrated closure rates over various lengths of follow-up from 37% to 85%, using a combination of autologous and allogenic mesenchymal and adipose-derived stem cells.79–85 Completion of Phase III trials is needed, but there is promising evidence that stem cells may aid in fistulizing pCD treatment.

Conclusion

Despite advancements in medical and surgical interventions for pCD, its treatment has remained challenging. Although current solutions for fistula management show varying degrees of success, additional research is needed to further the management of pCD. Current therapies, with the addition of a multidisciplinary team, will continue to improve the management of this difficult disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mary Kwatkosky-Lawlor for her assistance with the review process and the preparation of the bibliography.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):875–880. | ||

Tarrant KM, Barclay ML, Frampton CM, Gearry RB. Perianal disease predicts changes in Crohn’s disease phenotype–results of a population-based study of inflammatory bowel disease phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3082–3093. | ||

Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, Holmstrom B. Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1980;21(6):525–527. | ||

Williams DR, Coller JA, Corman ML, Nugent FW, Veidenheimer MC. Anal complications in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24(1):22–24. | ||

Faucheron JL, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, Parc R. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease – a sphincter-saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(2):208–211. | ||

Hatch Q, Champagne BJ, Maykel JA, et al. Crohn’s disease and pregnancy: the impact of perianal disease on delivery methods and complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(2):174–178. | ||

Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice C. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1508–1530. | ||

Tozer PJ, Whelan K, Phillips RK, Hart AL. Etiology of perianal Crohn’s disease: role of genetic, microbiological, and immunological factors. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(10):1591–1598. | ||

Irvine EJ. Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn’s disease as measured by a new disease activity index. McMaster IBD Study Group. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20(1):27–32. | ||

Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1398–1405. | ||

Schwartz DA, Wiersema MJ, Dudiak KM, et al. A comparison of endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and exam under anesthesia for evaluation of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1064–1072. | ||

Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9(2):98–103. | ||

Regueiro M. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12(3):621–633. | ||

Law PJ, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography: technique and normal anatomy. Gastrointest Radiol. 1989;14(4):349–353. | ||

Cheong DM, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD, Jagelman DG. Anal endosonography for recurrent anal fistulas: image enhancement with hydrogen peroxide. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(12):1158–1160. | ||

Navarro-Luna A, Garcia-Domingo MI, Rius-Macias J, Marco-Molina C. Ultrasound study of anal fistulas with hydrogen peroxide enhancement. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(1):108–114. | ||

Siddiqui MR, Ashrafian H, Tozer P, et al. A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of endoanal ultrasound and MRI for perianal fistula assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(5):576–585. | ||

Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, et al; World Gastroenterology Organization, International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD, European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials; World Gastroenterology Organization International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2014;63(9):1381–1392. | ||

Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Wilkinson K, Cohen RC, Kamm MA. The clinical course of fistulating Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(9):1145–1151. | ||

Dejaco C, Harrer M, Waldhoer T, Miehsler W, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W. Antibiotics and azathioprine for the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(11–12):1113–1120. | ||

Bernstein LH, Frank MS, Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Healing of perineal Crohn’s disease with metronidazole. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(3):599. | ||

Turunen UM, Farkkila MA, Hakala K, et al. Long-term treatment of ulcerative colitis with ciprofloxacin: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(5):1072–1078. | ||

Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ, Frank MS. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn’s disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(2):383–387. | ||

Jakobovits J, Schuster MM. Metronidazole therapy for Crohn’s disease and associated fistulae. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(7):533–540. | ||

Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):132–142. | ||

Hinterleitner TA, Petritsch W, Aichbichler B, Fickert P, Ranner G, Krejs GJ. Combination of cyclosporine, azathioprine and prednisolone for perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35(8):603–608. | ||

Egan LJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ. Clinical outcome following treatment of refractory inflammatory and fistulizing Crohn’s disease with intravenous cyclosporine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(3):442–448. | ||

Gurudu SR, Griffel LH, Gialanella RJ, Das KM. Cyclosporine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: short-term and long-term results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29(2):151–154. | ||

Sandborn WJ, Present DH, Isaacs KL, et al. Tacrolimus for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(2):380–388. | ||

Feagan BG, Rochon J, Fedorak RN, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. The North American Crohn’s Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(5):292–297. | ||

Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. North American Crohn’s Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(22):1627–1632. | ||

Arora S, Katkov W, Cooley J, et al. Methotrexate in Crohn’s disease: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(27):1724–1729. | ||

Mate-Jimenez J, Hermida C, Cantero-Perona J, Moreno-Otero R. 6-Mercaptopurine or methotrexate added to prednisone induces and maintains remission in steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(11):1227–1233. | ||

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):876–885. | ||

Parsi MA, Lashner BA, Achkar JP, Connor JT, Brzezinski A. Type of fistula determines response to infliximab in patients with fistulous Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(3):445–449. | ||

Choi CS, Berg AS, Sangster W, et al. Combined medical and surgical approach improves healing of septic perianal Crohn’s disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):506–514. e1. | ||

Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al; REACT Study Investigators. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10006):1825–1834. | ||

Lee MJ, Heywood N, Sagar PM, Brown SR, Fearnhead NS, p CD Collaborators. Surgical management of fistulating perianal Crohn’s disease – a UK survey. Colorectal Dis. Epub 2016 Jul 16. | ||

Solomon MJ. Fistulae and abscesses in symptomatic perianal Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1996;11(5):222–226. | ||

Hyder SA, Travis SP, Jewell DP, Mc CMNJ, George BD. Fistulating anal Crohn’s disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(12):1837–1841. | ||

Keighley MR, Allan RN. Current status and influence of operation on perianal Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1(2):104–107. | ||

Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, Lunniss PJ, Nicholls RJ, Cohen CR. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91(4):476–480. | ||

White RA, Eisenstat TE, Rubin RJ, Salvati EP. Seton management of complex anorectal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(7):587–589. | ||

Schwartz DA, Ghazi LJ, Regueiro M, et al; Crohn‘s & Colitis Foundation of America, Inc. Guidelines for the multidisciplinary management of Crohn’s perianal fistulas: summary statement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(4):723–730. | ||

Ritchie RD, Sackier JM, Hodde JP. Incontinence rates after cutting seton treatment for anal fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(6):564–571. | ||

Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Sasaki T, et al. Clinical advantages of combined seton placement and infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: when and how were the seton drains removed? Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57(97):3–7. | ||

Rakinic J. Anal fissure. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20(2):133–137. | ||

Halme L, Sainio AP. Factors related to frequency, type, and outcome of anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(1):55–59. | ||

Scott HJ, Northover JM. Evaluation of surgery for perianal Crohn’s fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(9):1039–1043. | ||

Taxonera C, Schwartz DA, Garcia-Olmo D. Emerging treatments for complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(34):4263–4272. | ||

Nordgren S, Fasth S, Hulten L. Anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: incidence and outcome of surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7(4):214–218. | ||

van Tets WF, Kuijpers HC. Continence disorders after anal fistulotomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(12):1194–1197. | ||

Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys MM, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ, George BD. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(12):1608–1615. | ||

Loungnarath R, Dietz DW, Mutch MG, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ, Fleshman JW. Fibrin glue treatment of complex anal fistulas has low success rate. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(4):432–436. | ||

Grimaud JC, Munoz-Bongrand N, Siproudhis L, et al; Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif. Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2275–2281, 2281 e2271. | ||

Champagne BJ, O’Connor LM, Ferguson M, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(12):1817–1821. | ||

Senejoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, et al; Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif [GETAID]. Fistula plug in fistulising ano-perineal Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(2):141–148. | ||

Rojanasakul A, Pattanaarun J, Sahakitrungruang C, Tantiphlachiva K. Total anal sphincter saving technique for fistula-in-ano; the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(3):581–586. | ||

Zirak-Schmidt S, Perdawood SK. Management of anal fistula by ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract – a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2014;61(12):A4977. | ||

Gingold DS, Murrell ZA, Fleshner PR. A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 2014;260(6):1057–1061. | ||

Parthasarathi R, Gomes RM, Rajapandian S, et al. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for the treatment of fistula-in-ano: experience of a tertiary care centre in South India. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(5):496–502. | ||

Kobayashi H, Sugihara K. Successful management of rectovaginal fistula treated by endorectal advancement flap: report of two cases and literature review. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:21. | ||

van Koperen PJ, Bemelman WA, Gerhards MF, et al. The anal fistula plug treatment compared with the mucosal advancement flap for cryptoglandular high transsphincteric perianal fistula: a double-blinded multicenter randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(4):387–393. | ||

Marchesa P, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Advancement sleeve flaps for treatment of severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1998;85(12):1695–1698. | ||

Grant DR, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Loop ileostomy for anorectal Crohn’s disease. Can J Surg. 1986;29(1):32–35. | ||

Zelas P, Jagelman DG. Loop illeostomy in the management of Crohn’s colitis in the debilitated patient. Ann Surg. 1980;191(2):164–168. | ||

Harper PH, Truelove SC, Lee EC, Kettlewell MG, Jewell DP. Split ileostomy and ileocolostomy for Crohn’s disease of the colon and ulcerative colitis: a 20 year survey. Gut. 1983;24(2):106–113. | ||

Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Surg. 2000;24(10):1258–1262; discussion 1262–1263. | ||

Lee E. Split ileostomy in the treatment of Crohn’s disease of the colon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1975;56(2):94–102. | ||

Hurst RD, Gottlieb LJ, Crucitti P, Melis M, Rubin M, Michelassi F. Primary closure of complicated perineal wounds with myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps after proctectomy for Crohn’s disease. Surgery. 2001;130(4):767–772; discussion 772–773. | ||

Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(8):893–898. | ||

Patsouras D, Yassin NA, Phillips RK. Clinical outcomes of colo-anal pull-through procedure for complex rectal conditions. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(4):253–258. | ||

Poggioli G, Laureti S, Pierangeli F, et al. Local injection of infliximab for the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(4):768–774. | ||

Tonelli F, Giudici F, Asteria CR. Effectiveness and safety of local adalimumab injection in patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(8):870–875. | ||

Soltani A, Kaiser AM. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn’s fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(4):486–495. | ||

Casson DH, Eltumi M, Tomlin S, Walker-Smith JA, Murch SH. Topical tacrolimus may be effective in the treatment of oral and perineal Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47(3):436–440. | ||

Hart AL, Plamondon S, Kamm MA. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease: exploratory randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(3):245–253. | ||

Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodriguez-Montes JA. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn’s fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1416–1423. | ||

Cho YB, Lee WY, Park KJ, Kim M, Yoo HW, Yu CS. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells for the treatment of Crohn’s fistula: a phase I clinical study. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(2):279–285. | ||

Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011;60(6):788–798. | ||

Lee WY, Park KJ, Cho YB, et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells treatment demonstrated favorable and sustainable therapeutic effect for Crohn’s fistula. Stem Cells. 2013;31(11):2575–2581. | ||

de la Portilla F, Alba F, Garcia-Olmo D, Herrerias JM, Gonzalez FX, Galindo A. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(3):313–323. | ||

Cho YB, Park KJ, Yoon SN, et al. Long-term results of adipose-derived stem cell therapy for the treatment of Crohn’s fistula. Stem Cells Translat Med. 2015;4(5):532–537. | ||

Garcia-Olmo D, Guadalajara H, Rubio-Perez I, Herreros MD, de-la-Quintana P, Garcia-Arranz M. Recurrent anal fistulae: limited surgery supported by stem cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(11):3330–3336. | ||

Molendijk I, Bonsing BA, Roelofs H, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote healing of refractory perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):918–927. e6. | ||

Hobbiss JH, Schofield PF. Management of perianal Crohn’s disease. J Royal Soc Med. 1982;75(6):414–417. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.