Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 11

Patient satisfaction with cardiac rehabilitation: association with utilization, functional capacity, and heart-health behaviors

Authors Ali S, Chessex C, Bassett-Gunter R, Grace SL

Received 23 August 2016

Accepted for publication 27 December 2016

Published 24 April 2017 Volume 2017:11 Pages 821—830

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S120464

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Saba Ali,1 Caroline Chessex,2 Rebecca Bassett-Gunter,1 Sherry L Grace1,2

1School of Kinesiology and Health Science, York University, 2Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Background: Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) societies recommend assessment of patient satisfaction given its association with health care utilization and outcomes. Recently, the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC, Glasgow) was recommended as an appropriate tool for the CR setting. The objectives of this study were to 1) describe patient satisfaction with CR, 2) test the psychometric properties of the PACIC in the CR setting, and 3) assess the association of patient satisfaction with CR utilization and outcomes.

Methods: Secondary analysis was conducted on an observational, prospective CR program evaluation cohort. A convenience sample of patients from 1 of 3 CR programs was approached at their first CR visit, and consenting participants completed a survey. Clinical data were extracted from charts pre- and post-program. Participants were e-mailed surveys again 6 months (including the PACIC) and 1 and 2 years later.

Results: Of 411 consenting patients, 247 (60.2%) completed CR. The mean PACIC score was 2.8±1.1/5. Internal reliability was α=0.95. The total PACIC score varied significantly by site (F=3.12, P=0.046), indicating discriminant validity. Patient satisfaction was significantly related to greater CR adherence (r=0.22, P<0.01) and completion (t=2.63, P<0.01), greater functional status at CR discharge (r=0.17, P=0.03) and 2 years post-intake (r=0.19, P=0.03), greater physical activity at discharge (r=0.18, P=0.02), as well as lower depressive symptoms at discharge (r=-0.16, P=0.02) and 1-year follow-up (r=-0.19, P=0.03). These associations sustained adjustment for sex.

Conclusion: Patients were relatively satisfied with their care. The PACIC is a psychometrically validated scale, which could serve as a useful tool to assess patient satisfaction with CR.

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, patient satisfaction, cardiovascular disease, program evaluation

Corrigendum for this paper has been published

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is considered to be a hallmark indicator of health care quality.1 It refers to a patient’s personal evaluation of health care received as well as of the provider.2 Patient satisfaction is conceived as multidimensional, comprising elements such as interpersonal manner, technical quality, accessibility/convenience, finances, efficacy/outcomes, continuity, physical environment, and availability.2 Patient satisfaction does not often correspond with objective reality or the perceptions held by providers or administrators regarding care.3 Patient satisfaction has been shown to be associated with a greater adherence to medical advice, health care utilization, and health outcomes,4,5 although mixed evidence is reported.6

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is an outpatient chronic disease management model recommended in clinical practice guidelines for patients with all forms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.7 In general, patients attend CR twice per week for over 4–6 months,8 during which time they receive the well-established core components of the model, namely risk factor assessment, structured exercise training, patient education, as well as dietary and psychosocial counseling.9 CR participation is associated with 20% lower cardiovascular mortality,10 with greater participation associated with greater benefits.11 Given the number of visits involved in CR, patient satisfaction may be key to CR adherence and subsequent health outcomes, including satisfaction with each of the core components.

Given the association between patient satisfaction and preventive health care utilization,12–14 and the importance of establishing the quality of CR services provided, several national CR associations recommend that patient satisfaction be assessed routinely.15,16 Despite these recommendations, there is little evidence available regarding patient satisfaction with CR. A recent review identified only 8 studies in this area.17 The scant published data suggest that patients have high satisfaction, in particular with staff and the motivating environment, information received regarding disease, information on diagnosis and treatment, and self-management of medicine.18,19 However, the existing studies had important limitations, including the use of non-validated questionnaires and lack of non-CR comparison groups.

Assessment of patient satisfaction requires proper tools and methods. This is particularly important because inflated satisfaction ratings often result when non-validated items are administered.20–22 Moreover, the administration of a generic or health care-specific satisfaction measure must be considered, as only the former can establish the degree of patient satisfaction when compared to a control group (ie, patients not exposed to a given health service). Psychometrically validated tools appropriate to measure patient satisfaction in CR have not been established; however, the recent review in this area17 recommended the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC).23 This tool assesses multiple dimensions of patient satisfaction, in accordance with Wagner’s Chronic Care Model.24 Therefore, the objectives of this study were to 1) describe, for the first time, patient satisfaction with CR using the recommended psychometrically validated scale, namely the PACIC; 2) test the PACIC as a psychometrically valid indicator of CR satisfaction specifically by assessing the scale’s a) internal reliability, b) discriminant validity (ie, whether the PACIC can capture variation in satisfaction across CR sites), and c) construct validity (ie, association with resources available to manage chronic illness) in a sample of cardiac outpatients referred to CR (of which not all enrolled); and 3) assess the association of patient satisfaction with CR program utilization and outcomes. Greater patient satisfaction was hypothesized to be associated with CR use (ie, shorter wait time, greater adherence, and completion), greater functional status, better heart-health behavior (ie, exercise, diet, medication adherence, and smoking), and psychological well-being (ie, depressive symptoms).

Methods

Design

This study was observational and prospective in design. Approval was received from the research ethics review boards at the institutions of each participating CR site (University Health Network Research Ethics Board and Research Ethics Board of Southlake Regional Health Centre [also board of record for Mackenzie Health]). Patients initiating CR at 1 of 4 centers were approached to participate between July 2010 and February 2014. Participants were asked to complete surveys at CR initiation and completion (or the expected time of graduation for those who did not complete), as well as 1 and 2 years from CR initiation. Clinical data were extracted from participants’ medical charts for their CR intake and discharge assessments (where available).

Setting

The cohort consisted of participants from 3 CR sites in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada, and 1 satellite program. The attributes of each site are described elsewhere.25 In brief, 3 of the programs were offered at no charge to participants, while the 3rd had a minimal charge for patients who had private health insurance coverage or can afford it. Two of the CR programs were located adjacent to a community hospital within a suburban setting, while the other was located within an academic hospital in an urban setting; its satellite program was on a university campus.

All programs offered CR in accordance with the Canadian Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (CACPR) Guidelines.9 Program frequency and duration varied by site; the program that was located in an academic hospital offered 90-minute classes twice per week, for a duration of 4 months. One community CR program offered 60- to 90-minute classes twice per week, and the other community and satellite programs offered 90-minute class once per week, each for 6 months. All programs offered patient education, on-site exercise programs, dietary counseling for groups or individuals, smoking cessation referrals, and psychosocial assessment/support.

Procedure

At their first CR visit, patients were approached to solicit written, informed consent by administrative staff at the site. Participants were asked to complete a self-administered survey in paper or online format. The survey assessed sociodemographic characteristics, heart-health behaviors (ie, exercise, nutrition, medication adherence), functional capacity, and depressive symptoms. Participants enrolling in the CR program completed an intake assessment as part of their standard care. This included risk factor assessment, an exercise stress test, and blood work (eg, lipid panel, glycated hemoglobin, or HbA1c). Data were extracted from charts.

The clinical assessment was repeated at the end of CR for those who completed the program. Available data were extracted from participants’ CR charts, including program utilization. A second survey was provided to all study participants centrally (regardless of CR program use), via mail and/or online. It not only assessed the same elements as noted earlier but also included wait times and the PACIC patient satisfaction measure.23 To optimize the response rate, at each assessment point, nonresponders were sent a repeat e-mail, and then they were contacted by telephone if they still had not responded.

A survey was also administered centrally to all study participants at 1 and 2 years’ post-intake, via mail and/or online. Heart-health behaviors, functional capacity, and depressive symptoms were again assessed. The Chronic Illness Resource Survey26 was also administered in the 2-year survey.

Participants

This convenience sample consisted of all consenting participants attending an initial visit at 1 of the 4 CR programs. Participants were referred to the CR programs with the following cardiac diagnoses or procedures: acute coronary syndrome, chronic stable angina, or stable heart failure, as well as percutaneous coronary or valvular intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) ± valve surgery, cardiac transplantation, or mild non-disabling stroke.9 The inclusion criterion was that participants were not deemed ineligible to complete CR upon initial assessment (ie, no comorbidities identified or indications from the exercise stress test that would preclude CR participation). Participants who were not proficient in the English language were excluded from the study.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics, such as participants’ ethnic origin (adapted from Statistics Canada categorizations), marital status, highest educational attainment, and work status, were assessed via self-report. Clinical data were extracted from CR referral forms, as well as CR intake and discharge assessments, where available. The following variables were collected: previous cardiac diagnoses, CR referral indications, cardiac risk factors (ie, blood pressure, lipids, blood glucose, and anthropometrics), and functional capacity that was obtained from the graded exercise stress tests (ie, peak metabolic equivalents of task [METs]).

Dependent variable: patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was measured using the PACIC (http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=PACIC_survey&s=36).23,27 It is a 20-item scale, consisting of 5 subscales that correspond to the elements of Wagner’s Chronic Care Model,24 namely 1) patient activation, 2) delivery system/practice design, 3) goal setting/tailoring, 4) problem solving/contextual, and 5) follow-up/coordination.23 Respondents were asked to indicate how often they experienced the content described in each item (eg, asked for ideas when making a treatment plan) on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (always). The subscales were scored by averaging responses to subscale items; the overall PACIC score is calculated by averaging scores across all 20 items. Higher scores denote greater satisfaction. In the initial validation, the internal reliability of the PACIC was α=0.93, indicating excellent reliability.23 The construct validity of the PACIC is supported by a significant, positive association with patient activation.28

The Chronic Illness Resource Survey26 was administered to compare with the PACIC, to get a sense of construct validity. This scale measures support and resources in 7 areas: doctor and health care team, family and friends, personal, neighborhood/community, media/policy, organization, and work. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which each resource/item was used over the past 6 months, on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). Items are averaged, with higher scores indicating greater resources in a given domain.

Independent variables

CR utilization was operationalized as program adherence (ie, ratio of sessions completed to those prescribed) and completion (ie, patient must have attended at least some of the CR intervention components and have had a formal re-assessment by the CR team at the conclusion of the CR intervention).29 Patients were also asked to report the number of weeks that passed between hospital discharge and CR initiation (ie, wait time).

The Duke Activity Status Index30 is a 12-item self-report scale, where patients are asked whether they can complete a list of activities of daily living. Each activity they can complete is weighted in terms of METs, and these are summed. Higher scores denote greater functional capacity. This scale correlates highly with peak oxygen uptake on cardiopulmonary assessments.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-831 is a reliable and validated depressive symptom screening scale, through which respondents are asked to report the frequency of depressed mood in the last 2 weeks. Each item is scored on a Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). A total score was computed by summing responses, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. A score of ≥10 was used to denote elevated depressive symptoms.

Heart-health behaviors

Participants were asked to self-report their smoking status. Next, the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire32 is a brief and reliable instrument to assess usual physical activity during a typical 1-week period. Frequencies of strenuous, moderate, and light-intensity activities were assessed. Higher scores indicate a greater amount of exercise. Those scoring >24 are believed to be physically active and those scoring <24 are considered insufficiently active.

The Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II33 nutrition subscale contains 6 statements that assess daily personal nutrition habits. Response options range from 1 (never) to 4 (routinely), indicating the frequency with which a particular nutrition behavior is practiced. A mean value was computed, with higher scores representing a healthier diet.

Finally, the 4-item version of Morisky Medication Adherence Scale34 was also administered. Response options are “yes” I agree with the statement (scored as 0) or “no” I do not (scored as 1). Responses are summed, and a total score of <4 indicates “non-adherence”.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A significance cut-off value of P<0.05 was applied throughout. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample by retention status. Chi-square or t-tests were used as appropriate.

Descriptive examination of patient satisfaction and its internal reliability were computed (Cronbach’s α). Values >0.60 are generally considered acceptable.35 Total patient satisfaction and subscale scores were compared by site using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with posthoc Tukey’s test. Finally, Pearson’s correlations were computed between the PACIC and the Chronic Illness Resource Survey.

To test the final objective, Pearson’s correlations were computed between the PACIC total score and the continuous independent variables. Student’s t-test or F-test was performed to test the association between the PACIC and any categorical independent variable (eg, CR completion). Given that these associations may be impacted by differences in patient satisfaction by sociodemographic or other characteristics,36 t-tests and correlations were run as applicable to ascertain whether patient satisfaction did vary by sex, age, ethnicity, and indication for CR (eg, CABG). Where significant, general linear models were constructed for the abovementioned significant independent variables, adjusting for the given characteristic.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Figure 1 displays the flow of participants through the study. As shown, 60% completed CR discharge assessments and thus were considered to have completed CR. Characteristics of participants retained at CR discharge versus those lost to follow-up are reported elsewhere.25 In summary, participants who completed CR were significantly less likely to have been referred due to arrhythmia, and more likely to have been prescribed acetylsalicylic acid at hospital discharge. No other differences were observed (data not shown).

| Figure 1 Participant flow diagram. |

As shown in Figure 1, less than half of participants completed the 2-year follow-up survey. Table 1 lists the pre-CR characteristics of participants retained 2 years later versus those lost to follow-up. With regard to sociodemographic characteristics, as shown, retained participants were more likely to self-report “North American” ethnocultural background versus any other origin (eg, European, Asian) compared to those lost to follow-up. With regard to clinical characteristics, retained participants were significantly more likely to have been referred to CR for an indication other than revascularization compared to those lost to follow-up. No other differences were observed.

| Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants at cardiac rehabilitation intake by 2-year survey completion |

Mean scores for the factors hypothesized to relate to patient satisfaction for each assessment point are listed in Table 2. Based on Godin scores >24,32 suggesting participants were meeting exercise guidelines of 150 minutes/week,37 154 (52.9%) participants were considered physically active at intake, 108 (62.1%) at the assessment point corresponding to CR discharge (some patients did not complete CR), 104 (64.6%) at 1 year, and 87 (56.9%) at 2 years from intake. With regard to depressive symptoms, 43 (9.3%) participants had symptom scores suggestive of major depression at intake, 18 (3.9%) post-program, 24 (5.2%) at 1 year, and 28 (6.0%) at 2 years from intake.

| Table 2 Independent variables and their association with patient satisfaction |

Patient satisfaction

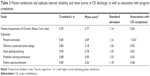

Mean patient satisfaction scores are shown in Table 3. Satisfaction was greatest for the delivery system/practice design subscale (ie, actions that organize care and provide information to patients to enhance their understanding of care) and lowest for the follow-up/coordination subscale (ie, making proactive contact with patients to assess progress and coordinate care). Internal reliability is also reported and should be considered excellent for the total scale and subscales.

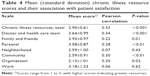

With regard to objective 2, PACIC total and subscale scores were compared by site (Figure 2). The total PACIC score varied significantly by site (F=3.12, P=0.046), indicating discriminant validity. As shown, post hoc tests revealed that patients reported significantly more satisfaction at sites 1 and 2 compared to site 3. There were significant site differences in 4 of the 5 subscales as well, namely patient activation (P=0.005), delivery system/practice design (P=0.02), goal setting (P=0.02), and problem solving (P=0.03). Post hoc tests again revealed that patients reported significantly more satisfaction in each of these domains at sites 1 and 2 compared to site 3. As shown in Table 4, greater total patient satisfaction was significantly related to greater overall resources to manage their chronic illness, as well as specific domains such as medical, family, personal, community, and organizational resources, suggesting construct validity.

| Table 4 Mean (±standard deviation) chronic illness resource scores and their association with patient satisfaction |

With regard to objective 3, as shown in Table 2, greater total patient satisfaction was significantly related to greater CR adherence and completion, greater functional status at CR discharge and 2 years post-intake, greater physical activity at discharge, as well as lower depressive symptoms at discharge and 1 year follow-up. There was a trend toward better diet at 2 years, but no other associations were observed.

With regard to CR completion more specifically, those who completed had a total PACIC score of 2.94±1.10 versus 2.48±1.17 for those who did not complete CR (P=0.009). The association of CR completion with PACIC subscales is shown in Table 3. Patients who completed CR had significantly greater satisfaction in all areas except follow-up/coordination compared to patients who did not complete CR.

Given that these associations may be confounded, the association of the PACIC with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics was assessed, to determine whether these should be taken into consideration in analyses. Total PACIC scores were not related to age (P=0.56), ethnic background (P=0.31), nor having CABG as an indication for CR (P=0.27). However, PACIC scores did differ significantly by sex (t=−2.10, P=0.04), with women (3.02±1.12) reporting significantly greater satisfaction than men (2.66±1.14). Therefore, the associations between the significant independent variables as summarized earlier and PACIC scores were each tested with adjustment for sex. As shown in Table 2, all models were significant overall, and the independent variables themselves remained significantly associated with patient satisfaction.

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge to have investigated patient satisfaction using the recommended generic and psychometrically validated measure in the CR setting.17 Results suggest that the PACIC23 is a reliable, valid, and sensitive measure of satisfaction for the CR setting. Patients were relatively satisfied with their chronic cardiac care, with those completing CR reporting greater satisfaction than those not completing.

The average PACIC score in this cohort was moderate (ie, 2.8/5, but closer to 3 in those completing CR). The PACIC has been administered in several other cohorts in Canada. For instance, mean overall satisfaction scores were somewhat lower among patients with diabetes, heart failure, arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from 33 primary care clinics (2.54) than observed in the present study, although satisfaction did vary based on the practice model.38 In another study of patients with hypertension, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from 9 academic family practices, satisfaction scores were very comparable to those in the present study at 2.8.39

The PACIC has also been administered in cardiac samples, but none in Canada to our knowledge. Comparable scores were again observed. For example, the PACIC was administered to patients with cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and stroke in the Netherlands, and the mean score was 2.9.40 Two cohorts of patients with type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and/or hypertension receiving care in Australian general practices were administered the PACIC questionnaire. Mean scores were somewhat higher at 3.0 and 3.1.41 Finally, the PACIC was also administered in a sample of patients with diabetes, chronic pain, heart failure, asthma, or coronary artery disease across a major Health Maintenance Organization in the US. The mean score (2.7) was quite similar to that reported in this cohort, indicating moderate levels of satisfaction.42 In summary, mean patient satisfaction ratings among cardiac patients in this sample were comparable to other chronic disease patients in the same health care system and to cardiac patients in other types of health care systems, with most ratings suggesting moderate satisfaction with care.

Greater patient satisfaction, as assessed via the PACIC, was associated with greater CR utilization, functional capacity, exercise, and fewer depressive symptoms. It was not associated with some other outcomes as hypothesized; however, it may not be realistic to expect that patient satisfaction with CR would be related to health behaviors over a year post-program. None of the previous studies on patient satisfaction with CR have explored the association of satisfaction with these outcomes. Clearly, more research is needed to understand whether high patient satisfaction is associated with greater recommendation adherence and better outcomes, and this must be tested in a rigorous, prospective fashion. Moreover, it should be tested whether improving elements of a CR program with which patients are unsatisfied will have an impact on their adherence to recommendations and ultimate outcomes.

Patient satisfaction was significantly lower with 1 of the CR programs than the other 2. This was 1 of the 2 community-based programs (ie, affiliated with a hospital, but located off-site), and annual patient volumes were in-between that of the other 2 sites; it was also 1 of 2 programs offering 2 formal CR sessions per week. The unique feature of the program is that patients paid a monthly fee to participate, which was reimbursable through private health care insurance for patients with such coverage (ie, through work or purchased privately). Patients may have had higher expectations as a result. Moreover, patients were welcome to continue in the program indefinitely (likely given they were paying; the other 2 programs had set graduation dates). The other potential explanations for lower satisfaction with this CR program could be different culture around patient–provider interactions, or patient dissatisfaction with individual staff members.43 In future research, co-administration of a CR-specific satisfaction measure and some qualitative, open-ended questions regarding reasons for patient satisfaction would facilitate interpretation of these site differences.

Implications and directions for future research

The PACIC enables comparison of patient satisfaction in patients attending CR versus non-attenders. The incorporation of a comparison group is key to establishing patient satisfaction with CR overall. However, for the purposes of improving CR program delivery, staff should also administer an ancillary measure assessing patient satisfaction with various components of the program as well. The Cardiac Rehabilitation Preference Form is one such tool, as it measures the extent to which patient preferences for specific CR program components are being met.44 Where CR administrators understand with which aspects of the program patients are dissatisfied, they could then modify these elements of the program to increase satisfaction and hopefully ultimately improve CR use, heart-health behaviors, and associated outcomes. For example, if patients express dissatisfaction with center hours, they could be modified. If patients express dissatisfaction with the interactions with staff, continuing education could be offered to staff and the program could examine the time that staff have to devote to patient-centered interactions.

Limitations

Caution is warranted when interpreting the findings. 1) The representativeness of the cohort is unknown, as the CR sites did not record which CR patients were approached to participate but declined. Consenting patients may have had particular psychological characteristics (such as high motivation and perseverance) that set them apart from patients who did not, and this could have affected the results that were observed. Thus, selection bias may be at play. 2) Many of the independent variables were self-reported, which raises the possibility of expectation bias and socially desirable responding. However, the dependent variable of patient satisfaction is a patient-reported outcome, and hence it is appropriate that this was self-reported and bias is not a concern. 3) Due to the rates of 1- and 2-year follow-up survey completion, retention bias is a possibility. However, very few differences in participant characteristics were observed between those retained and those lost to follow-up. 4) The design of the study was not randomized, and therefore alternative explanations for patient satisfaction ratings cannot be ruled out, and causal conclusions cannot be drawn. For example, the association between depressive symptoms and patient satisfaction is likely reversed, such that the patients who were more depressed reported lower satisfaction. 5) Multiple tests of association between patient satisfaction and outcomes were performed, which would increase the potential for Type I error. 6) The generalizability of the study results to other CR programs is unknown; however, 4 centers were considered herein.

Conclusion

The PACIC is a psychometrically validated scale that could indeed serve as a useful tool to assess patient satisfaction in the CR setting. The PACIC is a reliable, valid, and also sensitive measure, such that comparison can be made across CR programs. Patient satisfaction with their chronic cardiac care was moderate overall. Greater patient satisfaction was significantly associated with greater CR adherence and completion, greater functional status, and lower depressive symptoms. CR program staff should assess patient satisfaction, in order to better understand degree of their satisfaction, and where lacking, to optimize it to ultimately improve CR use and associated outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Terry Fair, BEd, Cynthia Parson, BSc, PT, RPT, and Ann Briggs, BSc, PT, RPT, for facilitating patient recruitment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. | ||

Ware JE Jr, Snyder MK, Wright WR, Davies AR. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6(3–4):247–263. | ||

Chang JT. Patients’ global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665. | ||

Hofer R, Choi H, Mase R, Fagerlin A, Spencer M, Heisler M. Mediators and moderators of improvements in medication adherence: secondary analysis of a Community Health Worker-Led Diabetes Medication Self-Management Support Program. Health Educ Behav. 2016. Epub 2016 Jul 14. | ||

Jha A, Orav E, Zheng J, Epstein A. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;18(359):1921–1931. | ||

Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin RGS. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–203. | ||

Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(23):2432–2446. | ||

Polyzotis PA, Tan Y, Prior PL, Oh P, Fair T, Grace SL. Cardiac rehabilitation services in Ontario: components, models and underserved groups. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13(11):727–734. | ||

Stone JA, Arthur H, editors. Canadian Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Translating Knowledge into Action. 3rd ed. Winnipeg, MB: Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation; 2009. | ||

Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(1):1–12. | ||

Martin B-J, Hauer T, Arena R, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation attendance and outcomes in coronary artery disease patients. Circulation. 2012;126(6):677–687. | ||

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(3):229–239. | ||

Fenton JJ, Jerant A, Bertakis K, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405. | ||

Biondi EA, Hall M, Leonard MS, Pirraglia PA, Alverson BK. Association between resource utilization and patient satisfaction at a tertiary care medical center. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):785–791. | ||

Woodruffe S, Neubeck L, Clark RA, et al. Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(5):430–441. | ||

Piepoli MF, Corra U, Adamopoulos S, et al. Secondary prevention in the clinical management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for referral and delivery: a policy statement from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. Endorsed by the Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;21(6):664–681. | ||

Taherzadeh G, Filippo DE, Kelly S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2016;36:230–239. | ||

Andraos C, Arthur HM, Oh P, Chessex C, Brister S, Grace SL. Women’s preferences for cardiac rehabilitation program model: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(12):1513–1522. | ||

Soja AMB, Zwisler A-DO, Nissen N, et al [webpage on the Internet]. Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation improves self-estimated health and patient satisfaction-important factors in future risk factor and life style management. In: European Heart Journal Conference: European Society of Cardiology. 2009. Available from: http://spo.escardio.org/eslides/view.aspx?eevtid=33&fp=3170. Accessed January 4, 2016. | ||

Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(32):1–244. | ||

Kahn KL, Liu H, Adams JL, et al. Methodological challenges associated with patient responses to follow-up longitudinal surveys regarding quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 pt 1):1579–1598. | ||

Ware JJ. Effects of acquiescent response set on patient satisfaction ratings. Med Care. 1978;16(4):327–336. | ||

Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43(5):436–444. | ||

Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(2):63–80. | ||

Somanader D, Chessex C, Ginsburg L, Grace SL. The Quality and Variability of Cardiac Rehabilitation Delivery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. In press 2017. | ||

Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Barrera M, Strycker L. The Chronic Illness Resources Survey: cross-validation and sensitivity to intervention. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(4):402–409. | ||

Clinical Practice Change [webpage on the Internet]. Improving chronic illness care; 2006–2017. Available from: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=PACIC_survey&s=36. Accessed July 7, 2016. | ||

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 pt 1):1918–1930. | ||

Grace SL, Poirier P, Norris CM, et al; Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Pan-Canadian development of cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention quality indicators. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(8):945–948. | ||

Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64(10):651–654. | ||

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. | ||

Godin G, Shephard R. Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1985;29(6):36–38. | ||

Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987;36(2):76–81. | ||

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(5):348–354. | ||

Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. | ||

Chen H, Li M, Wang J, et al. Factors influencing inpatients’ satisfaction with hospitalization service in public hospitals in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:469–477. | ||

Tremblay MS, Warburton DER, Janssen I, et al. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:36–46. | ||

Lévesque JF, Feldman DE, Lemieux V, Tourigny A, Lavoie JP, Tousignant P. Variations in patients’ assessment of chronic illness care across organizational models of primary health care: a multilevel cohort analysis. Healthc Policy. 2012;8(2):108–123. | ||

Houle J, Beaulieu M, Lussier M-T, et al. Patients’ experience of chronic illness care in a network of teaching settings. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(12):1366–1373. | ||

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. High-quality chronic care delivery improves experiences of chronically ill patients receiving care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(6):689–695. | ||

Taggart J, Chan B, Jayasinghe UW, et al. Patients Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) in two Australian studies: structure and utility. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):215–221. | ||

Schmittdiel J, Mosen DM, Glasgow RE, Hibbard J, Remmers C, Bellows J. Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and improved patient-centered outcomes for chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(1):77–80. | ||

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. | ||

Moore SM, Kramer FM. Women’s and men’s preferences for cardiac rehabilitation program features. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1996;16(3):163–168. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.